Abstract

The endothelial cell protein C/activated protein C receptor (EPCR) is located primarily on the surface of the large vessels of the vasculature. In vitro studies suggest that it is involved in the protein C anticoagulant pathway. We report the organization and nucleotide sequence of the human EPCR gene. It spans approximately 6 kbp of genomic DNA, with a transcription initiation point 79 bp upstream of the translation initiation (Met) codon in close proximity to a TATA box and other promoter element consensus sequences. The human EPCR gene has been localized to 20q11.2 and consists of four exons interrupted by three introns, all of which obey the GT-AG rule. Exon I encodes the 5′ untranslated region and the signal peptide, and exon IV encodes the transmembrane domain, the cytoplasmic tail, and the 3′ untranslated region. Exons II and III encode most of the extracellular region of the EPCR. These exons have been found to correspond to those encoding the 1 and 2 domains of the CD1/major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I superfamily. Flanking and intervening introns are of the same phase (phase I) and the position of the intervening intron is identically located. Secondary structure prediction for the amino acid sequence of exons II and III corresponds well with the actual secondary structure elements determined for the 1 and 2 domains of HLA-A2 and murine CD1.1 from crystal structures. These findings suggest that the EPCR folds with a β-sheet platform supporting two -helical regions collectively forming a potential binding pocket for protein C/activated protein C.

THE PROTEIN C anticoagulant system is a well-established pathway regulating thrombin generation and therefore clot formation (reviewed in Esmon1 and Simmonds and Lane2). Regulation is achieved via the degradation of procoagulant activated factors V and VIII by a serine proteinase, activated protein C (APC), in conjunction with its nonenzymatic cofactor, protein S. When thrombin binds to the endothelial cell transmembrane protein, thrombomodulin, its potent procoagulant functions are reversed and its substrate specificity is redirected towards protein C.1,3 Protein C (the zymogen of APC) is then activated on the surface of endothelial cells by the thrombin/thrombomodulin complex. Mutations in the genes for thrombomodulin,4,5 protein C,6 and protein S7 have been identified in patients with venous and/or arterial thrombosis, highlighting the importance of this pathway.

Recently, this model of protein C activation has been shown to be a simplification; an additional endothelial cell-specific transmembrane protein has been identified that binds protein C and APC on the cell surface.8 This novel protein was named the endothelial cell protein C/APC receptor (EPCR). Direct binding between protein C and the EPCR (kd, ∼30 nmol/L) has also been demonstrated,9 and this is dependent on the Gla domain of protein C.8 The EPCR itself does not have any direct anticoagulant effect in the absence of APC, because its addition to plasma does not increase the clotting time,10 and APC bound to the EPCR looses its anticoagulant ability to inactivate activated factor V.10 However, the EPCR influences the rate of protein C activation by the thrombin/thrombomodulin complex.11 If protein C binding to the EPCR is blocked, then the rate to protein C activation is reduced by approximately 80%. The important function of the EPCR is thought to be anticoagulant, as an accessory protein in the activation of protein C.

Thrombomodulin is known to have a uniform distribution on all endothelial cells, which results in an effective 100-fold decrease in thrombomodulin concentration in large vessels compared with capillaries due to geometric considerations.12 On the surface of the large vessels, this would have been expected to result in inefficient activation of the protein C anticoagulant pathway, because the affinity between thrombomodulin and protein C is weak. However, the EPCR has since been found to be restricted primarily to the surface of the endothelium of arteries and veins, with very little found on capillary endothelial cells.13 Together with the high affinity of the protein C/EPCR interaction, this should result in the effective localization of protein C on the surface of the endothelium, leading to an increase in local concentration. It has been suggested that this ensures efficient protein C activation on the surface of the large vessels.

A soluble form of the EPCR (43 kD) has been identified in human plasma collected from healthy individuals.14 It circulates at a concentration of approximately 2.5 nmol/L, well below the kd for the protein C/EPCR interaction, suggesting that, in healthy individuals, this form is physiologically unimportant. However, soluble EPCR purified from plasma can bind both protein C and APC and blocks the anticoagulant function of APC.14

The human EPCR cDNA is 1.3 kbp in size and encodes a protein of 238 amino acids.8 It has a molecular weight of approximately 46 kD, which is larger than that predicted based on amino acid sequence (25 kD), probably due to the presence of carbohydrate located at 4 potential N-glycosylation sites in the coding region. After the removal of 17 residues during processing, the mature protein is predicted to consist of 221 amino acids.9,14 To date, additional cDNAs for the murine and bovine EPCR have been described,15although, until now, the gene encoding the EPCR has not been described for any species.

The contribution of the EPCR to the regulation of coagulation and the prevention of thrombus formation in vivo is, as yet, unknown. The investigations outlined above strongly suggest that it is important. Dysfunction of the human EPCR gene may lead to failure of endogenous anticoagulation and thrombosis. Also, at present, there is little information regarding the three-dimensional structure of the EPCR. Amino acid sequence homology has been noted,8 which suggested similarities to the CD1/major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I superfamily. The greatest homology is between the EPCR and CD1d (17% at the amino acid level in humans). To facilitate additional investigations of the role of the EPCR in physiology and pathology and to further investigate the domain structure of the protein, we have studied the organization and established the chromosomal location of the human EPCR gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Amplification of regions of the EPCR gene by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Amplification of DNA samples by PCR was performed using Taq DNA polymerase and standard methods.16 The template for amplification was either genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes of a healthy individual, P1 artificial chromosome (PAC), or plasmid DNA isolated from transformed bacteria. All amplifications were primed by pairs of chemically synthesized gene-specific 17- or 18-mer oligonucleotides (Fig 1 and Table 1). These were designed based on either the published human EPCR cDNA sequence8 or from genomic sequence derived as described below. Reaction conditions have been described elsewhere.17 Exon-specific primer pairs EPCR-3 and EPCR-4 as well as EPCR-5 and EPCR-8 (Fig 1 and Table 1) had previously been identified. These were capable of amplifying regions of genomic DNA that corresponded in size and DNA sequence to that expected from the EPCR cDNA sequence (data not shown).

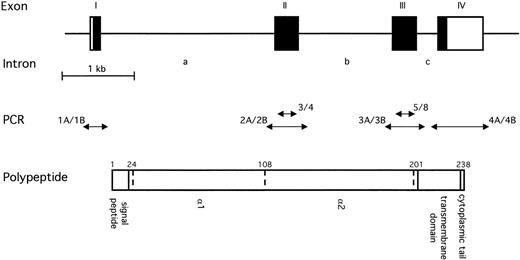

Schematic representation of the human EPCR gene. The upper diagram shows the overall intron/exon structure of the gene, which consists of four exons (I to IV) and three introns (a to c). Black regions represent the coding regions; white regions represent the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions to the left and right, respectively. The scale of this diagram is given below the gene. The double headed arrows in the centre represent fragments of the EPCR gene that were amplified from various templates by PCR. Fragment 3/4 resulted from amplification using primers EPCR-3 and EPCR-4; 5/8 resulted from amplification of EPCR-5 and EPCR-8 (Table 1). These primer pairs were exon-specific. Fragments 1A/1B, 2C/2B, 3A/3B, and 4A/4B were amplified using primer pairs EP1A and EP1B, EP2C and EP2B, EP3A and EP3B, and EP4A and EP4B (Table 1). Use of these primers resulted in the amplification of each exon and its associated intron/exon boundaries. The lower diagram represents the EPCR polypeptide. The position of the introns within the amino acid sequence are represented by dotted lines. The residue number is indicated above the position of each intron. The signal peptide, extracellular regions, transmembrane domain, and cytoplasmic tail are also indicated.

Schematic representation of the human EPCR gene. The upper diagram shows the overall intron/exon structure of the gene, which consists of four exons (I to IV) and three introns (a to c). Black regions represent the coding regions; white regions represent the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions to the left and right, respectively. The scale of this diagram is given below the gene. The double headed arrows in the centre represent fragments of the EPCR gene that were amplified from various templates by PCR. Fragment 3/4 resulted from amplification using primers EPCR-3 and EPCR-4; 5/8 resulted from amplification of EPCR-5 and EPCR-8 (Table 1). These primer pairs were exon-specific. Fragments 1A/1B, 2C/2B, 3A/3B, and 4A/4B were amplified using primer pairs EP1A and EP1B, EP2C and EP2B, EP3A and EP3B, and EP4A and EP4B (Table 1). Use of these primers resulted in the amplification of each exon and its associated intron/exon boundaries. The lower diagram represents the EPCR polypeptide. The position of the introns within the amino acid sequence are represented by dotted lines. The residue number is indicated above the position of each intron. The signal peptide, extracellular regions, transmembrane domain, and cytoplasmic tail are also indicated.

Synthetic Oligonucleotide Primers Used to Amplify Genomic, PAC, and Plasmid DNA by PCR

| Primer ID . | Sequence* . | Position . |

|---|---|---|

| EPCR-3 | ACCTAACGCACGTGCTGG | 2634 to 2651† |

| EPCR-4 | AGGTCCGCTCCTGGTGC‡ | 2791 to 2776† |

| EPCR-5 | GGAGCTCCTTTGTGAGTT | 4103 to 4120† |

| EPCR-8 | AATTCCCGCAGTTCATAC‡ | 4235 to 4218† |

| EP1A | AGACGGTCCTCACTTCTC | −94 to −77† |

| EP1B | GATAGACTGAGATTCTCC‡ | 118 to 99† |

| EP2C | GAGTTACTGTCAGCGTCA | 2383 to 2400† |

| EP2B | CCCAGCAATCTTCAAAGG‡ | 2957 to 2940† |

| EP3A | ACACCTGGCACCCTCTCT | 3164 to 3981† |

| EP3B | CATCCTTCAGGTCCATCC‡ | 4370 to 4353† |

| EP4A | GACTCAAATCATGGACTC | 4484 to 4501† |

| EP4B | CCCAACTCCATTATCTGT‡ | 4948 to 4931† |

| RACE-2 | AGCAGCGGATGGTCAGAGGA | 367 to 3481-153 |

| RACE-9 | GTTGCCCTGGTACCACACGT | 165 to 1471-153 |

| RACE-11 | TGAGGCGTCTTGGCTACA | 90 to 731-153 |

| Primer ID . | Sequence* . | Position . |

|---|---|---|

| EPCR-3 | ACCTAACGCACGTGCTGG | 2634 to 2651† |

| EPCR-4 | AGGTCCGCTCCTGGTGC‡ | 2791 to 2776† |

| EPCR-5 | GGAGCTCCTTTGTGAGTT | 4103 to 4120† |

| EPCR-8 | AATTCCCGCAGTTCATAC‡ | 4235 to 4218† |

| EP1A | AGACGGTCCTCACTTCTC | −94 to −77† |

| EP1B | GATAGACTGAGATTCTCC‡ | 118 to 99† |

| EP2C | GAGTTACTGTCAGCGTCA | 2383 to 2400† |

| EP2B | CCCAGCAATCTTCAAAGG‡ | 2957 to 2940† |

| EP3A | ACACCTGGCACCCTCTCT | 3164 to 3981† |

| EP3B | CATCCTTCAGGTCCATCC‡ | 4370 to 4353† |

| EP4A | GACTCAAATCATGGACTC | 4484 to 4501† |

| EP4B | CCCAACTCCATTATCTGT‡ | 4948 to 4931† |

| RACE-2 | AGCAGCGGATGGTCAGAGGA | 367 to 3481-153 |

| RACE-9 | GTTGCCCTGGTACCACACGT | 165 to 1471-153 |

| RACE-11 | TGAGGCGTCTTGGCTACA | 90 to 731-153 |

DNA sequence analysis.

All DNA sequence analysis was performed using the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method18 with the ABI PRISM Big Dye terminator cycle-sequencing ready reaction kit (Perkin Elmer, Applied Biosystems Division, Foster City, CA) and an automated detection system (ABI PRISM 373 stretch XL; Perkin Elmer). Each reaction was primed using a gene-specific 17- or 18-mer oligonucleotide in an appropriate position/orientation to obtain the DNA sequence of the newly synthesized strand. To obtain the EPCR gene sequence from cloned fragments, a primer walking approach was used in which new oligonucleotides were designed based on the 3′ sequence obtained from previous reactions. Initial reactions used the exon-specific primer pairs mentioned above. M13 forward and reverse primers were used to sequence across vector/insert boundaries. To obtain the DNA sequence of amplification products, the reactions were primed with the same oligonucleotides used in the amplification reaction. Sequences were assembled using Assemblylign software (Eastman Kodak Inc, Rochester, NY). All DNA sequences reported were determined at least once in each direction.

Preparation of an EPCR cDNA probe.

The probe used to screen the genomic DNA library, in Southern blots and colony lifts (see below) was an expressed sequence tag (EST) representing the human EPCR cDNA, obtained as an I.M.A.G.E. clone.19 It was identified by searching the National Centre for Biotechnology Information EST database with the first 40 nucleotides of the published human EPCR cDNA sequence.8I.M.A.G.E. clone 327665 was found to have a DNA sequence identical to the published EPCR cDNA sequence, with the exception of three nucleotides at positions 679, 1043, and 1044. An additional 44 bp of 5′ untranslated sequence was present in the clone and the site of poly-A addition to the cDNA was different from that previously reported at nucleotide 1118. This was 16 bp downstream of an alternative polyadenylation signal sequence (AATAAA) at position 1097 to 1102 in the cDNA (Fig2). In view of these small differences, it was felt that the clone 327665 represented the human EPCR cDNA and it is referred to as such throughout this communication. It should be noted that all cDNA and amino acid numbering used here is in accordance with Fukudome and Esmon.8 The probe for subsequent hybridization reactions was prepared by restriction digestion of I.M.A.G.E. clone 327665 withNot I and Xho I, releasing a 1.2-kbp fragment that included the entire coding region of the EPCR. This fragment was gel-purified and radioactively labeled with 32P-dCTP using the random priming method [Ready-To-Go DNA kit (-dCTP); Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden]. After removal of unincorporated nucleotides and primers, the probe was used directly in hybridization reactions.

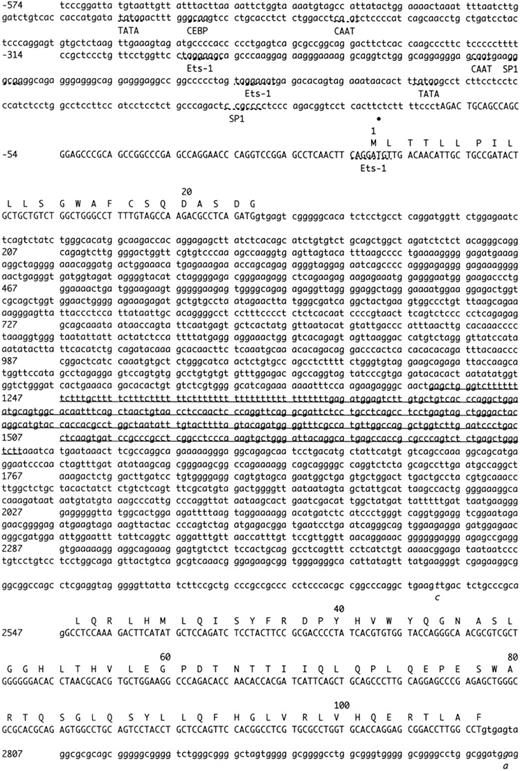

Complete nucleotide sequence of the human endothelial cell protein C/APC receptor gene. Numbering is relative to the first nucleotide of the translation start (Met) codon (+1). Numbers on the left-hand side denote the number of the first nucleotide on that line. Uppercase letters denote a sequence that has been isolated as mRNA or cDNA, lowercase letter denote 5′ and 3′ flanking sequence and introns. The bullet point under the sequence represents a transcription initiation site (C-79). Putative regulatory elements in the 5′ region of the gene are indicated by broken lines and the name of the element. Two alternative polyadenylation sites in the 3′ region of the gene are also indicated by broken lines. The exon sequences correspond with the EPCR cDNA sequence previously published, except for 3 nucleotides (double underlined). Intronic sequences that are potentially polymorphic are indicated with italics. Three Alu repetitive elements within introns and in the 3′ flanking sequence are underlined. An EcoRI site (GAATTC) in exon III is also indicated. CEBP, CAAT enhancer binding protein.

Complete nucleotide sequence of the human endothelial cell protein C/APC receptor gene. Numbering is relative to the first nucleotide of the translation start (Met) codon (+1). Numbers on the left-hand side denote the number of the first nucleotide on that line. Uppercase letters denote a sequence that has been isolated as mRNA or cDNA, lowercase letter denote 5′ and 3′ flanking sequence and introns. The bullet point under the sequence represents a transcription initiation site (C-79). Putative regulatory elements in the 5′ region of the gene are indicated by broken lines and the name of the element. Two alternative polyadenylation sites in the 3′ region of the gene are also indicated by broken lines. The exon sequences correspond with the EPCR cDNA sequence previously published, except for 3 nucleotides (double underlined). Intronic sequences that are potentially polymorphic are indicated with italics. Three Alu repetitive elements within introns and in the 3′ flanking sequence are underlined. An EcoRI site (GAATTC) in exon III is also indicated. CEBP, CAAT enhancer binding protein.

Determination of the complete nucleotide sequence of the human EPCR gene.

To obtain the complete sequence of the gene encoding the human EPCR, a human genomic PAC library was screened for clones that hybridized with the EPCR cDNA. The library, RPCI1,20 was obtained from the Human Genome Mapping Project (HGMP) and was constructed in the vector pCYPAC2. The library was screened by hybridization to the EPCR cDNA probe using standard techniques.21 Three clones hybridized strongly: 198-F17, 212-C5, and 212-F6 (data not shown). The presence of exonic regions of the EPCR gene in these clones was confirmed by amplification with primers EPCR-3 and EPCR-4 (data not shown).

Southern blot analysis of the genomic PAC clones that hybridized with the EPCR cDNA probe was performed using standard techniques.21 PAC DNA was digested with EcoRI andNot I. Not I was included in the reaction, because restriction sites for this endonuclease were present in pCYPAC2, flanking the cloning site. Cleavage at these positions therefore resulted in the release of the entire genomic DNA insert. Filters were screened with the EPCR cDNA probe, as described above. PAC 212-C5 contained the largest portion of genomic DNA with the EPCR gene and was chosen for further analysis. Two fragments of DNA (9.5 and 1.5 kbp) that hybridized with the EPCR cDNA were identified in this clone (data not shown). The overall size of the EPCR gene was therefore predicted to be less than 11 kbp.

The PAC clone 212-C5 was digested with the restriction endonucleaseEcoRI, and all resulting fragments were subcloned into the cloning vector pGEM-3Z (Promega, Madison, WI) using highly competent JM109 Escherichia coli (Promega) and standard methods. Clones with the EPCR gene containing fragments were identified by colony hybridization.22 The probe in the hybridization was the EPCR cDNA, which is described above. One clone selected by hybridization, termed EPCRg6, contained solely the 9.5-kbp fragment mentioned above. To isolate the 1.5-kbp fragment, a further subcloning step was required, producing in the clone EPCRg11. The sequence of the entire EPCR gene was obtained by sequencing clones EPCRg6 and EPCRg11 in both directions, as described above. Intron/exon boundaries were located by comparison of the cDNA and genomic DNA sequences. The integrity of exon sequence was investigated by amplification of each identified exon and its associated intron/exon boundaries. The templates were genomic DNA samples from healthy individuals, which were amplified using primer pairs EP1A and EP1B, EP2C and EP2B, EP3A and EP3B, and EP4A and EP4B (Fig 1 and Table 1). Amplification products were sequenced as described above.

Determination of transcription initiation sites by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE).

The transcription initiation site(s) were identified by 5′ RACE using a commercially available kit (5′ RACE system Version 2; GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Poly-A+ RNA was isolated from human umbilical vein endothelial cells using the Oligotex direct mRNA kit (QIAgen, Valencia, CA). This was used as a template for first-strand cDNA synthesis in a reaction primed by the oligonucleotide RACE-2 (Table 1). After removal of RNA from the reaction and poly-C anchor addition, cDNA was then used as the template in heminested PCR, primed by the Abridged Anchor Primer supplied with the kit and the oligonucleotide RACE-9 (Table 1). Amplification products were diluted 1 in 500 and used as the template in a further nested amplification reaction. Here, the primers used were Abridged Universal Amplification Primer and the oligonucleotide RACE-11 (Table 1). The products of 5′ RACE were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and cloned directly into the TA cloning vector pCR 2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using the topoisomerase method. The complete DNA sequence of the 5′ RACE product(s) was then obtained, as described above.

Determination of the chromosomal location of the EPCR gene.

The chromosomal location of the EPCR gene was determined by use of a human monochromosomal somatic cell hybrid DNA panel obtained from HGMP.23 This consisted of a panel of DNA samples from mouse/human or hamster/human somatic cell hybrids, with each being almost monochromosomal. DNA in the panel was amplified by PCR, as described above, using primers EPCR-3 and EPCR-4 (Fig 1 and Table 1). Amplified DNA was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel. The regional assignment of the EPCR gene was determined by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), which was performed according to standard procedures.24 Slides were prepared from phytohemagglutinin-stimulated peripheral blood cultures. PAC DNA was labeled with biotin by nick-translation and was detected with fluoroscein isothiocyanate after hybridization. The chromosomes were background-stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were captured using an Olympus Vanox fluorescence microscope equipped with a CCD camera and SmartCapture software (Vysis, Downers Grove, IL). The DAPI-banding pattern was enhanced and converted to greyscale with SmartCapture software to enable chromosome and band assignation.

Computer analysis.

Potential transcription factor binding sites were identified in the 5′ flanking sequence of the EPCR gene using a transcription factor database TRANSFAC25 (Molecular Bioinformatics of Gene Regulation, Braunschweig, Germany) in conjunction with MatInspector software (GSF-National Center for Environment and Health, Neuherberg, Germany).26 The secondary structure of the EPCR, based on amino acid sequence, was predicted by the use of six different computational algorithms: PHD,27,28 ssp,29 Gibrat,30Levin,31 DPM,32 and SOPMA.33 The consensus for assigning a secondary structure element (α-helix [H] or β-sheet [E]) to a particular residue was if three or more algorithms predicted that element. Amino acid sequences were optimally aligned using clustalW software.34 To calculate the degree of residue conservation between exons II and III of the EPCR and the α1 and α2 domains of CD1 proteins and HLA-A2, each pair of sequences was first optimally aligned. The number of conserved (identical) residues was then counted and expressed as a percentage of the total compared regions (including gaps introduced for optimal alignment).

RESULTS

Organization and complete nucleotide sequence of the human EPCR gene.

Approximately 6 kbp of cloned genomic DNA (EPCRg6 and EPCRg11) has been sequenced, including 5′ and 3′ flanking sequence, exons, and introns (Fig 2). The nucleotides of the gene have been numbered relative to the first nucleotide of the translation initiation (Met) codon. The EPCR gene consists of four exons of 138, 252, 279, and 659 bp (determined from both cloned and amplified genomic DNA; Figs 1 and2). Exon I (amino acids 1 to 24) encodes the 5′ untranslated region, the signal peptide, and 7 additional residues. Exons II (amino acids 24 to 108) and III (amino acids 108 to 201) encode the extracellular region of the EPCR. Exon IV (amino acids 201 to 238) encodes an additional 10 residues of the extracellular portion of the EPCR, the transmembrane domain, the cytoplasmic tail, and the 3′ untranslated region. The exons are interrupted by three introns of 2477, 1217, and 251 bp (Fig 2). All of the splice donor and acceptor sites obey the GT-AG rule and largely agree with consensus sequences35 (Table 2). All splice junctions of the EPCR gene are in phase I, ie, after the first nucleotide of the triplet codon for amino acids 24, 108, and 201. Introns a and b both contain an Alu repetitive element present on the complementary strand. These span from 1230 to 1590 in intron a and from 3417 to 3747 in intron b (Fig 2).

Comparison of the Intron/Exon Boundaries of the Human EPCR Gene With the Consensus Sequences for These Regions

| Exon* . | . | Intron* . | Exon* . | Phase . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | GATG | GTGAGTCG.......a......AAGTTGACTCTGCCCGCAG | GCC | II | I | |

| II | GCCT | GTGAGTAG.......b......CCTGACTGTCTATCCACAG | TTC | III | I | |

| III | AAAG | GTATGATG.......c......CTCTTTGCATGTTCTGCAG | GGA | IV | I | |

| Consensus† | ||||||

| NAG | GTAAGTN................NTNTTTTTTTTTTTNCAG | GN | ||||

| G CCC CCCCCC | ||||||

Two potentially polymorphic sites have been identified within the intronic regions of the human EPCR gene (Fig 2). The sequence of the amplified genomic DNA fragment containing exon II was heterozygous at position 2532, 16 bp upstream of the start of exon II, where both C and T nucleotides were observed. This polymorphism is close enough to the intron/exon boundary to suggest potential differences in splicing efficiency, although this has not been tested. The amplified genomic DNA fragment containing this sequence variation was also heterozygous at position 2894, 85 bp downstream of the end of exon II, where both A and G were observed. This latter change is unlikely to have an effect on splicing.

The clone EPCRg6 contained sequence located upstream of anEcoRI site (GAATTC) located in exon III of the EPCR gene, whereas EPCRg11 contained sequence downstream of this position (Fig 2). The absence of additional gene sequence between EPCRg6 and EPCRg11 was confirmed by amplification and sequencing of a genomic DNA sample with EP3A (located in EPCRg6) and EP3B (located in EPCRg11).

To identify a transcription start site for the human EPCR gene, 5′ RACE analysis was used. After two rounds of heminested PCR amplification, an amplification product of approximately 240 bp was identified by agarose gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Using DNA sequence analysis, the transcription initiation site was identified as nucleotide C-79 for this fragment (Fig 2). Under lower stringency amplification conditions, products corresponding to transcripts terminated at A-83 were also found. The entire sequence of the cloned fragment corresponded to EPCR gene sequence obtained from EPCRg6. The transcription start site is 26 bp downstream of an SP1 binding site (on the reverse strand, CCGCCC) and 84 bp downstream of a TATA box element (TATAA). Additional potential transcription factor binding sites were identified in the 5′ flanking sequence of the EPCR gene using computer analysis. Complete agreement with consensus sequences of the core binding sites and surrounding nucleotides was found in several locations (Fig 2). In the 3′ region of the human EPCR gene, there are two alternative polyadenylation sites (AATAAA) at positions 5017 and 5186 (Fig 2). There is an additional Alu repeat, also on the complementary strand, in this region of the gene (position 5280 to 5594; Fig 2).

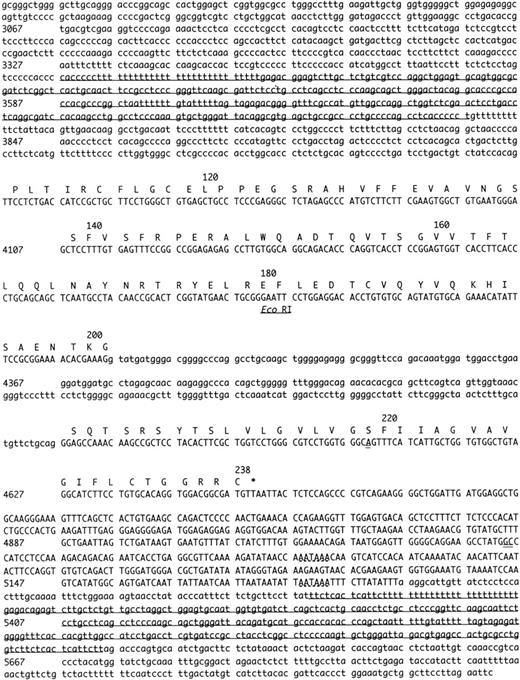

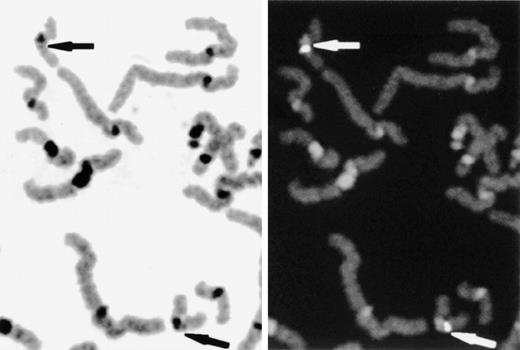

The EPCR gene was initially assigned to a chromosome by amplification of a monochromosomal cell hybrid DNA panel with exon-specific primers (EPCR-3 and EPCR-4; Fig 1 and Table 1). Amplification of mouse and hamster control DNAs was not possible under the conditions used (Fig 3, lanes 26 and 27). An amplification product corresponding to the EPCR gene was observed in the human genomic DNA controls (Fig 3, lanes 25 and 28) and also the hybrid that contained chromosome 20 (Fig 3, lane 20). This hybrid may also contain fragments of other chromosomes. However, the absence of an amplification product in the hybrids containing all other whole chromosomes confirmed that the EPCR gene is located on chromosome 20. This finding was confirmed by FISH and further localized the gene to position 20q11.2, near the centromere, in all of the cells examined (Fig 4). Results for PAC 212-C5 hybridization to a single typical cell have been shown here. These findings were reproduced in all cells examined and when another PAC clone (198-F17) was used. The single hybridization position confirmed that these clones were not chimeric.

Chromosomal assignment of the human EPCR gene. A human monochromosomal somatic cell hybrid DNA panel and controls were amplified by PCR to determine the chromosomal location of the EPCR gene. The exon-specific primers EPCR-3 and EPCR-4 (Table 1) were used and the products were separated on a 1% agarose gel. The templates in lanes 1 to 24 were mouse/human or hamster/human somatic cell hybrids containing chromosomes 1 to 22, X and Y chromosomes, respectively. Lanes 25 and 28 were human genomic DNA samples; one was provided with the panel (lane 25) and one was our internal control (lane 28). Lanes 26 and 27 were mouse and hamster genomic DNA, respectively. The marker lane (M) is pHC624/Taq I-pMJ/Nci I (Advanced Biotechnologies, Leatherhead, UK). This contains fragments of 1444, 696, 475, 411, 358, 352, 212, and 96 bp (the 358- and 352-bp fragments comigrate).

Chromosomal assignment of the human EPCR gene. A human monochromosomal somatic cell hybrid DNA panel and controls were amplified by PCR to determine the chromosomal location of the EPCR gene. The exon-specific primers EPCR-3 and EPCR-4 (Table 1) were used and the products were separated on a 1% agarose gel. The templates in lanes 1 to 24 were mouse/human or hamster/human somatic cell hybrids containing chromosomes 1 to 22, X and Y chromosomes, respectively. Lanes 25 and 28 were human genomic DNA samples; one was provided with the panel (lane 25) and one was our internal control (lane 28). Lanes 26 and 27 were mouse and hamster genomic DNA, respectively. The marker lane (M) is pHC624/Taq I-pMJ/Nci I (Advanced Biotechnologies, Leatherhead, UK). This contains fragments of 1444, 696, 475, 411, 358, 352, 212, and 96 bp (the 358- and 352-bp fragments comigrate).

Determination of the regional assignment of the EPCR gene by FISH. Slides were prepared from phytohemagglutinin-stimulated peripheral-blood cultures and hybridized with biotin labeled PAC DNA. The chromosomes were background-stained with DAPI. The DAPI-banding pattern was enhanced and converted to greyscale with SmartCapture software to enable chromosome and band assignation (left panel). Hybridized PAC DNA was detected using fluorescein isothiocyanate (right panel). Specific fluorescent signals and the locus 20q11.2 are indicated by arrows.

Determination of the regional assignment of the EPCR gene by FISH. Slides were prepared from phytohemagglutinin-stimulated peripheral-blood cultures and hybridized with biotin labeled PAC DNA. The chromosomes were background-stained with DAPI. The DAPI-banding pattern was enhanced and converted to greyscale with SmartCapture software to enable chromosome and band assignation (left panel). Hybridized PAC DNA was detected using fluorescein isothiocyanate (right panel). Specific fluorescent signals and the locus 20q11.2 are indicated by arrows.

Similarity between the human EPCR, CD1, and MHC class I genes.

An optimal alignment of the amino acid sequences encoded by exons II and III of the EPCR gene and those exons that encode the α1 and α2 domains of murine CD1.1 and HLA-A2 is displayed in Fig 5. Interestingly, the location of the intervening intron is identical and those of the flanking exons are similar. The phase of these introns in murine CD1.136 and HLA-A237 are identical to human EPCR (see above and Fig 2). The secondary structure elements of these exons of the EPCR gene (II and III), once expressed, were predicted using six different computational algorithms (see Materials and Methods). The consensus predicted secondary structure from this analysis is also displayed in Fig 5, together with the secondary structure elements of murine CD1.1 and HLA-A2 taken from the previously resolved crystal structures.38 39 It can clearly be seen that the secondary structure motifs found in murine CD1.1 and HLA-A2 are predicted to be conserved in the EPCR. Furthermore, two cysteine residues in the α2 domains of both murine CD1.1 and HLA-A2 (known to form a disulphide bridge from both crystal structures) are conserved in the precisely the same positions in the EPCR.

Similarities between the EPCR and the 1 and 2 domains of CD1 and MHC class I antigen-presenting molecules. The amino acids encoded by exons II and III of the human EPCR gene (hEPCR) and the 1 and 2 domains of murine CD1.1 (mCD1.1, homologous to human CD1d40) and HLA-A2 (hHLA-A2) have been optimally aligned using clustalW.34 The position of flanking and intervening introns are indicated with a solid line. In all cases, the introns are in phase I (ie, after the first nucleotide of the triplet code). Secondary structure elements are indicated by light (-helix) and dark (β-sheet) shaded areas. For CD1.1 and HLA-A2, these were taken from crystal structures.38 39 For hEPCR, these represent the consensus from six secondary structure prediction algorithms (see Materials and Methods). The location of a disulphide bond identified in the crystal structures of murine CD1.1 and HLA-A2 is indicated by a solid line. This is likely to link the two highly conserved cysteine residues in the EPCR.

Similarities between the EPCR and the 1 and 2 domains of CD1 and MHC class I antigen-presenting molecules. The amino acids encoded by exons II and III of the human EPCR gene (hEPCR) and the 1 and 2 domains of murine CD1.1 (mCD1.1, homologous to human CD1d40) and HLA-A2 (hHLA-A2) have been optimally aligned using clustalW.34 The position of flanking and intervening introns are indicated with a solid line. In all cases, the introns are in phase I (ie, after the first nucleotide of the triplet code). Secondary structure elements are indicated by light (-helix) and dark (β-sheet) shaded areas. For CD1.1 and HLA-A2, these were taken from crystal structures.38 39 For hEPCR, these represent the consensus from six secondary structure prediction algorithms (see Materials and Methods). The location of a disulphide bond identified in the crystal structures of murine CD1.1 and HLA-A2 is indicated by a solid line. This is likely to link the two highly conserved cysteine residues in the EPCR.

The conservation between the amino acids encoded by exons II and III of the EPCR gene and between the α1 and α2 domains of murine CD1.1 and HLA-A2 is summarized in Table 3. Human CD1d has been included in this analysis because it has the closest similarity to the EPCR8 and it is the human homologue of murine CD1.1,40 with 59% conservation in the α1 and α2 domains (Table 3). For all other pairwise comparisons, the α1 and α2 domains have between 11% and 29% conservation when these domains are considered separately and between 16% and 27% if they are considered together (Table 3). The proportion of conserved residues between a CD1 and an MHC class I protein are therefore of the same order as that found between either the EPCR and CD1 or EPCR and MHC class I in the α1 and α2 domains. The greatest conservation in these regions was still found with human CD1d (Table 3).

Amino Acid Conservation Between the EPCR and the 1 and 2 Domains of the CD1 and MHC Class I Proteins

| . | . | hCD1d3-150 . | mCD1.13-151 . | hHLA-A23-152 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 . | α2 . | α1 + 2 . | α1 . | α2 . | α1 + 2 . | α1 . | α2 . | α1 + 2 . | ||

| hEPCR3-153 | α1 | 24% | 17% | 18% | ||||||

| α2 | 29% | 26% | 16% | |||||||

| α1 + 2 | 27% | 22% | 17% | |||||||

| hCD1d | α1 | — | 58% | 11% | ||||||

| α2 | — | 59% | 23% | |||||||

| α1 + 2 | — | 59% | 17% | |||||||

| mCD1.1 | α1 | — | — | 15% | ||||||

| α2 | — | — | 17% | |||||||

| α1 + 2 | — | — | 16% | |||||||

| . | . | hCD1d3-150 . | mCD1.13-151 . | hHLA-A23-152 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 . | α2 . | α1 + 2 . | α1 . | α2 . | α1 + 2 . | α1 . | α2 . | α1 + 2 . | ||

| hEPCR3-153 | α1 | 24% | 17% | 18% | ||||||

| α2 | 29% | 26% | 16% | |||||||

| α1 + 2 | 27% | 22% | 17% | |||||||

| hCD1d | α1 | — | 58% | 11% | ||||||

| α2 | — | 59% | 23% | |||||||

| α1 + 2 | — | 59% | 17% | |||||||

| mCD1.1 | α1 | — | — | 15% | ||||||

| α2 | — | — | 17% | |||||||

| α1 + 2 | — | — | 16% | |||||||

All α1 and α2 domains were defined by the exon structure of the respective genes. Each pair of amino acid sequences was optimally aligned using clustalW software.34 The number of conserved (identical) residues was then counted and is expressed as a percentage of the total compared regions (including gaps introduced for optimal alignment).

Human CD1d, exons 2 and 3.36

Murine CD1.1, exons 2 and 3.47

Human HLA-A2, exons 2 and 3.37

Human EPCR, exons II and III (this report).

DISCUSSION

The human EPCR gene spans approximately 6 kbp genomic DNA and consists of four exons (I to IV) interrupted by three introns (a to c). In the 5′ region of the gene, we identified a transcription start site by 5′ RACE. This technique uses a gene-specific primer to generate first-strand cDNA and further gene-specific primers to amplify this. The template for first-strand cDNA synthesis was poly-A+ RNA purified from human umbilical vein endothelial cells, which express the EPCR on the cell surface.8 The identification of sequence that corresponded to the human EPCR gene (and previously unidentified as cDNA) indicated that the gene is active in these cells. The presence of multiple potential transcription factor binding sites surrounding the transcription start site further emphasizes its functionality. The transcription initiation site was localized to nucleotide C-79 (Fig 2). This is 84 bp downstream of a TATA box element (TATAA), which may be important in initiation of EPCR gene expression. Complete agreement with consensus sequences of the core binding sites and surrounding nucleotides for other transcription factors was found in several locations (referred to by the 5′ nucleotide of the core consensus). Of particular interest were SP1 binding sites at positions −236 and −105, two CAAT box elements (positions −436 and −243), and a CAAT enhancer binding protein recognition sequences (positions −462). Also, three Ets-1 binding sites (positions −293, −194, and −3) were found that matched the consensus sequence G/CA/CGGAA/TGC/T in 7, 6, and 8 nucleotides, respectively (Fig 2).

During computer analysis of the putative promoter region, a TATA box element containing all 15 nucleotides of the consensus was identified at position −474 (Fig 2). A possible translation initiation codon (Met) is present at position −374, approximately 100 bp downstream of this element, but its significance is uncertain. It is unlikely that this TATA box element is important for EPCR expression due to its distance from the transcription initiation site (389 bp). No 5′ RACE products were identified corresponding to initiation near this TATA box and including the Met codon of the EPCR gene. It therefore seems that the TATA box element at −474, if active, is unrelated to the EPCR.

Similarity between the EPCR and the CD1/MHC class I superfamily has previously been noted,8 particularly in the α1 and α2 domains of these latter proteins. This lead to the suggestion that the EPCR extracellular region also consisted of two discreet modules. However, detailed consideration of the EPCR structure was not possible, because the boundaries of structural units were undefined. The relationship between the EPCR and antigen-presenting molecules has been confirmed and extended in the present study.

Exons II and III of the EPCR gene code for amino acids 24 to 201 of the EPCR protein (Fig 2) and account for almost the entire extracellular domain. The amino acids encoded by these regions will be referred to as the extracellular region of the EPCR in this discussion, although it should be noted that an additional 7 and 10 residues of the EPCR (encoded by exons I and IV, respectively) are likely to be exposed on the cell surface. The flanking and intervening introns of exons II and III are all in phase I. This is identical with the phase of the corresponding introns (ie, adjacent to the α1 and α2 domains) of all the CD1 and MHC class I genes studied to date.40 When the amino acids in the α1 and α2 domains (defined by the exons encoding them) of a typical CD1 (murine CD1.1, homologue of human CD1d) and MHC class I protein (HLA-A2) were optimally aligned with the extracellular region of the EPCR, the position of the intervening intron was found to be in an identical position (Fig 5).

A previous search with the complete polypeptide chain of the human EPCR identified the greatest sequence similarity with human CD1d,8 with an overall residue conservation of 17%. Comparison of the α1 and α2 exons of CD1d36 with exons II and III of the EPCR (this report) shows 27% conservation (Table 3). Although these figures are quite low, previous studies have shown that these functional protein domains can tolerate a large variation in amino acid content without affecting their overall structure. For example, murine CD1.1 and HLA-A2 have 16% amino acid sequence conservation in the α1 and α2 domains (Table 3). The x-ray crystal structures of both these proteins have been determined.38,39,41 Given the low amino acid conservation between the two, an unexpected structural similarity is observed.39

Crystal structures of several other MHC class I proteins have been determined, although at present, this has not been achieved for the CD1 family. In all structures, the α1 and α2 domains have a characteristic three-dimensional structure, located distal from the transmembrane region and separated from it by the α3 domain and β-2 microglobulin.42 In simplified terms, α1 and α2 form a platform of 7 or 8 β-sheets supporting 2 α-helical regions (1 from α1 and 1 from α2). The exons encoding each of the α1 and α2 domains encode amino acids that adopt a secondary structure organization EEE(E)H (where E is β-sheet and H is α-helix; Fig 5). There is a conserved disulphide bond between a cysteine residue adjacent to the first β-sheet and α-helical region of the α2 domain. The peptide binding pocket is provided by the groove between the 2 α-helical regions and residues of the β-sheets that are exposed to solvent at the bottom of the groove.42

The degrees of amino acid conservation between the human EPCR extracellular region and the murine CD1.1 or HLA-A2 α1 and α2 domains are of the same order as those between HLA-A2 and murine CD1.1 (Table 3). Like these latter two proteins, and despite the low amino acid conservation, the secondary structure seems to have been conserved for the EPCR: secondary structure prediction for the EPCR (Fig 5) corresponds well with the determined secondary structure elements of the related proteins shown by the crystal structures, ie, in the pattern HEEEEH (α1) then EEEHH (α2). Both conserved cysteine residues involved in the α2 disulphide bond of CD1/MHC class I proteins are also present in the EPCR and are highly likely to be bonded similarly (Fig 5). Taking all of this information together, it can be predicted that the structure of the EPCR is similar to that of the α1 and α2 domains of the CD1/MHC class I superfamily. The protein C/APC binding site may therefore be provided by a groove similar to that found in CD1/MHC class I proteins. It also seems likely that the EPCR and CD1/MHC class I are evolutionarily related.

The similarity between the EPCR and antigen-presenting molecules may well extend to the signal peptide (ie, exon I; data not shown), although the more widely conserved nature of this structural unit makes this difficult to evaluate. However, there is no region homologous to the α3 domain in the EPCR gene, and in CD1/MHC class I genes, the transmembrane, cytoplasmic, and 3′ untranslated regions are encoded by between 2 and 4 exons.40,43 The EPCR gene may therefore have evolved by selective insertion of the α1 and α2 domains and possibly the signal peptide. The greater similarity between the EPCR and CD1d suggests that duplication/insertion occurred after the divergence of the CD1 gene family. It might be expected that the Alu repetitive elements identified here in the intronic sequences of the EPCR gene played a role in the insertion event; however, no Alu repetitive elements flanking the α1 and α2 domains of the human CD1 genes have been reported.36,44 This implies that the Alu elements were inserted at a later time. This is supported by the finding that the intron between α1 and α2 is much larger in the EPCR gene (1.2 kbp compared with ∼0.5 kbp in the CD1 family36 44). It will be interesting to see whether Alu elements are present in analogous positions in the EPCR gene of other species.

We have localized the EPCR gene to chromosome 20 at position q11.2 (Figs 3 and 4). The CD1 and MHC gene clusters are found on chromosomes 1 and 6, respectively, and are therefore not expected to be linked to the EPCR. However, the gene for thrombomodulin, the other endothelial cell receptor essential for protein C activation, is also located on chromosome 20 in position 20p12 to cen.45 46

The predicted structure of the extracellular region of the EPCR in this study gives a basis for further experiments into its function. Furthermore, the complete nucleotide sequence will facilitate clinical studies into the role of the EPCR in pathological states.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr Andrew Chase and Antonella Adami for help with FISH.

Supported by a grant from the British Heart Foundation (Grant No. PG/97029).

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been submitted to GenBank with accession no. AF106202.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

The complete nucleotide sequence of the murine EPCR gene has recently been published: Liang Z, Rosen ED, and Castellino FJ: Thromb Haemost 81:585, 1999.

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Rachel E. Simmonds, PhD, Department of Haematology, Imperial College School of Medicine, Charing Cross Campus, St Dunstan’s Road, London W6 8RP, UK; e-mail: r.simmonds@ic.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal