Abstract

Platelet activation leads to secretion of granule contents and to the formation of microvesicles by shedding of membranes from the cell surface. Recently, we have described small internal vesicles in multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and -granules, and suggested that these vesicles are secreted during platelet activation, analogous to the secretion of vesicles termed exosomes by other cell types. In the present study we report that two different types of membrane vesicles are released after stimulation of platelets with thrombin receptor agonist peptide SFLLRN (TRAP) or -thrombin: microvesicles of 100 nm to 1 μm, and exosomes measuring 40 to 100 nm in diameter, similar in size as the internal vesicles in MVBs and -granules. Microvesicles could be detected by flow cytometry but not the exosomes, probably because of the small size of the latter. Western blot analysis showed that isolated exosomes were selectively enriched in the tetraspan protein CD63. Whole-mount immuno-electron microscopy (IEM) confirmed this observation. Membrane proteins such as the integrin chains IIb-β3 and β1, GPIb, and P-selectin were predominantly present on the microvesicles. IEM of platelet aggregates showed CD63+ internal vesicles in fusion profiles of MVBs, and in the extracellular space between platelet extensions. Annexin-V binding was mainly restricted to the microvesicles and to a low extent to exosomes. Binding of factor X and prothrombin was observed to the microvesicles but not to exosomes. These observations and the selective presence of CD63 suggest that released platelet exosomes may have an extracellular function other than the procoagulant activity, attributed to platelet microvesicles.

PLATELET ACTIVATION encompasses a variety of cellular responses, including shape change, translocation of membrane glycoproteins, exocytosis of granule contents, and the formation of microvesicles. Formation of microvesicles has been demonstrated in vitro using flow cytometry after stimulation with the agonists calcium ionophore A23187, thrombin, collagen, and the thrombin receptor agonist peptide SFLLRN.1,2 Microvesicles have also been shown in the absence of agonists, under conditions of high shear stress.3,4 In vivo they have been observed in a standardized bleeding time wound,5 and in clinical situations associated with platelet activation, including idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura6 and cardiopulmonary bypass.7 Although the physiological role of platelet microvesicles remains to be established, both procoagulant8,9 and anticoagulant10 activity have been attributed to them. Formation of microvesicles is closely associated with the exposure of phosphatidylserine at the outer membrane leaflet of the platelet cell surface. Exposure of phosphatidylserine has also been described on the outer membrane leaflet of released microvesicles,11,12 and it provides an anionic surface for the binding of coagulation factors VIII,13 Va,14 and Xa.15 Thus, microvesicles have the potential to exert a procoagulant function at a distance from the site of platelet activation. Platelet microvesicles contain several platelet surface glycoproteins (GP) such as GPIb, the integrin chains αIIb β3 and β15,7,16 and also P-selectin,5which is translocated from intracellular compartments to the cell surface after activation. The presence of these glycoproteins on released microvesicles may be of importance for their interaction with other cells17 or with fibrin.18

Extracellular vesicles can also originate from exocytosis of endocytic multivesicular bodies (MVBs), by which the internal vesicles are released from the cell as so-called exosomes.19 This phenomenon has been shown in several cell types, in particular in cells of the hematopoietic lineage (B cells, T cells, dendritic cells, monocytes, and reticulocytes). For example, fusion of the multivesicular MHC class II compartment (MIIC) with the plasma membrane in B-cell lines generates exosomes in the medium,20analogous to the release of exosomes during exocytosis of multivesicular cytolytic granules in cytotoxic T lymphocytes.21 Exosomes may be involved in specific extracellular functions like antigen presentation20,22 and target cell killing.23

We have recently identified MVBs and subclasses of α-granules as multivesicular compartments,24 and have suggested that these internal vesicles are released during platelet activation as exosomes. In the present article we report that during platelet activation two distinct vesicle populations are released: a population of vesicles derived from the plasma membrane (microvesicles), and a separate population of exosomes. Because of their different origin and specific protein composition, platelet exosomes may have an extracellular function beside the procoagulant activity attributed to platelet microvesicles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

The D-arginyl-glycyl-L-aspartyl-L-tryptophan (dRGDW) peptide was generously provided by Dr J. Bouchaudon (Rhone-Poulenc-Rorer, Chemistry Department, Centre de Recherche de Vitry, Vitry sur Seine, France). The thrombin-receptor activating peptide (TRAP) ser-phen-leu-leu-arg-asn (SFLLRN) was from Bachem Feinchemikalien AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylcholine (PC), and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) were from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Prothrombin was isolated from freshly frozen human citrated plasma using a barium citrate precipitation as previously described.25 Human factor X was purified from plasma as described by Hackeng et al.26 Human α-thrombin was kindly provided by Dr W. Kisiel (Department of Pathology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM).

Antibodies.

The following monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) were purchased: CLB-Gran1/2, 435 (IgG1, CD63). Monoclonal AK-3 (IgG1, GPIb) and polyclonal anti–Peta-3 were kindly provided by Dr M.C. Berndt (Prahan, Australia). Biotin-conjugated monoclonal anti-RUU-SP 1.18 (P-selectin) and biotinylated anti-CD63 were from our own department (Hematology, University Hospital, Utrecht, The Netherlands). In flow cytometry, RUU-SP 1.18 detects P-selectin exposed on the cell surface after activation. AK-6 MoAb directed to P-selectin was from Serotec (Serotec Ltd, Oxford, UK). Monoclonal ALB-6 (CD9) was a kind gift of Dr E. Rubinstein (Inserm U268, Villejuif, France). Rabbit polyclonal anti-β1 was kindly provided by Dr K.M. Yamada (Bethesda, MD). Monoclonal anti–annexin-V (WAC 27b) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated annexin-V were a gift from Dr C. Reutelingsperger (University of Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands). Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-prothrombin antibody and polyclonal anti-FX were from our own department (Hematology, University Hospital, Utrecht, The Netherlands). FITC-conjugated MoAb anti-GPIb, FITC-conjugated streptavidin, polyclonal anti-vWF, polyclonal anti-FITC, and rabbit anti-mouse IgG were from DAKO (Glostrup, Denmark).

Platelet isolation.

Whole blood, obtained from healthy donors who had not used aspirin in the preceding week, was anticoagulated with 1/10 vol of 0.13 mol/L sodium citrate. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was obtained by centrifugation at 180g for 10 minutes at 22°C. The PRP was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with Krebs Ringer buffer, pH 5.0 (4 mmol/L KCl, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 20 mmol/L NaHCO3, 2 mmol/L Na2SO4, 4.7 mmol/L citric acid, 14.2 mmol/L tri-sodium citrate), and the platelet pellet was washed twice with the same buffer at pH 6.0. Finally, samples of the washed platelet suspension were resuspended in Krebs-Ringer buffer (pH 7.4), containing 100 μmol/L of the αIIb-β3 inhibitor dRGDW to prevent platelet aggregation. EDTA (5 mmol/L final concentration) was added to the suspension just before activation to prevent aggregation of released vesicles, and 5 mmol/L (final concentration) of the protease inhibitor 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzene sulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) was also added to the suspension.

Isolation of vesicles.

Microvesicles and exosomes were isolated from 5 mL releasates of 4 to 12 × 106/μL washed platelets. The platelet suspension described above was stimulated with 15 μmol/L TRAP (fc) for 10 minutes at 37°C and centrifuged at 750g for 20 minutes (platelet fraction). The supernatant platelet releasate was placed on ice and centrifuged at 10,000g for 30 minutes at 4°C to obtain the microvesicle fraction (104-g fraction). The supernatant was resuspended in 2.0 mol/L sucrose in 20 mmol/L HEPES/1 mmol/L EDTA, pH 7.2 and a sucrose gradient (0.8 mol/L to 0.25 mol/L sucrose in 20 mmol/L HEPES/1 mmol/L EDTA, pH 7.2) was layered on top of this fraction. The gradient was centrifuged at 65,000g for 16 hours at 4°C using an SW50.1 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Inc, Fullerton, CA), and 500-μL fractions were collected from the top of the gradient. The fractions were diluted in 4.5 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.1 mol/L sodium phosphate, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, pH 7.4), with 5 mmol/L EDTA added, and ultracentrifuged for 60 minutes at 200,000g using an SW50.1 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Inc). Samples of the pellets were solubilized in reducing or nonreducing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer, incubated for 5 minutes at 95°C, and analyzed by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting using 125I-protein G. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA assay from Pierce Chemical Co (Rockford, IL). For electron microscopy, the fractions were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (see below).

Flow cytometry.

Washed platelets were activated with 15 μmol/L TRAP or 1 U/mL of α-thrombin. The samples were diluted to a concentration of 3 × 108 platelets/mL, and 40-μL aliquots were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with specific antibodies. To detect platelets and microvesicles, FITC-conjugated monoclonal anti-GPIb or biotinylated anti–P-selectin antibody (RUU-SP 1.18) were used. For detection of exosomes a biotinylated anti-CD63 antibody (5 μg/mL) was used. Binding of the biotinylated antibodies was monitored with FITC-conjugated streptavidin. An irrelevant nonplatelet antibody and FITC-conjugated streptavidin alone were used as controls. From each sample 5,000 positive events in the platelet gate were analyzed in a Facs Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) at a wavelength of 488 nm. Fluorescence and light scatter data were obtained at logarithmic settings. The samples were analyzed on the basis of their forward scatter and 90° light scatter profile, using special gate thresholds to detect platelets and microvesicles.4 Samples of isolated exosome fractions were analyzed using biotinylated anti-CD63 antibody.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Samples of each pellet were run on 7.5%, 10%, or 12.5% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bradford, MA). The membranes were blocked for 90 minutes in PBS containing 5% (wt/vol) nonfatty dry milk Protifar (Nutricia, Zoetermeer, The Netherlands), and 0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 20, then incubated for 90 minutes with primary antibodies followed by incubation with 0.1 μg/mL 125I-labeled protein G (Zymed Lab, San Francisco, CA). For detection of MoAbs, a polyclonal anti-mouse IgG was used as intermediate. The radioactivity of all fractions was quantified with a Phospho-Imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Electron microscopy and immunogold cytochemistry.

Electron microscopic analysis was performed on isolated vesicle fractions as follows. Immediately after the 200,000gcentrifugation step, the pellets were resuspended in 30 μL PBS (pH 7.4) containing 5 mmol/L EDTA and fixed by adding an equal volume of 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). All fractions from the gradient were adsorbed for 10 minutes to formvar-carbon coated grids by floating the grids on 5 μL drops on parafilm. Grids with adhered vesicles were rinsed in PBS and examined in the electron microscope after uranyl staining and embedding (as described below).

Exocytosis was examined in platelet aggregates formed after 5 minutes of stimulation with 1 U/mL α-thrombin, in the absence of dRGDW and EDTA. After fixation with a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), the samples were infiltrated in 2.3 mol/L sucrose and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The subcellular localization of CD63 and GPIb was studied on ultrathin cryosections of platelet aggregates.

Immunogold labeling of vesicle fractions and of ultrathin cryosections was performed at room temperature by floating the grids on drops containing the diluted antibodies, essentially as described previously.27 After immunolabeling, the samples were washed in distilled water, stained for 5 minutes with uranyl-oxalate, pH 7.0, washed again, and embedded in a mixture of 1.8% methyl cellulose and 0.3% uranyl acetate at 4°C.28 Double immunogold labeling was performed essentially as described previously.29Briefly, single-labeled vesicle fractions were put successively on drops containing PBS, 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS (5 minutes), PBS/0.02% glycine, and PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) before starting the next immuno incubation. We used protein-A gold sizes of 5 nm and 10 nm for the double labeling experiments. The specificity of immunolabeling was verified using an irrelevant control antibody and protein-A gold alone.

Binding of annexin-V, prothrombin, and factor X.

For annexin-V binding studies, isolated exosome fractions were resuspended in 100 mmol/L HEPES containing 5 mmol/L CaCl2(HEPES/CaCl2). The fractions were adsorbed for 10 minutes to formvar-carbon coated grids by floating them on 5-μL drops on parafilm. The grids were washed on successive drops of HEPES/CaCl2, blocked with 0.1% BSA in HEPES/CaCl2, and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with 10 μg/mL FITC-conjugated annexin-V in the presence of 5 mmol/L CaCl2. After 3 rinses with HEPES/CaCl2, the vesicle fractions were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde in HEPES/CaCl2 and immediately used for immunogold labeling as described above, using a rabbit polyclonal anti-FITC antibody and 10 nm protein A gold.

In a similar way, the binding of prothrombin and factor X was monitored to isolated exosomes, microvesicles, and phospholipid vesicles. Phospholipid vesicles containing 20% PS, 40% PC and 40% PE were prepared as described by van Wijnen et al.30All vesicle samples were adsorbed for 10 minutes to formvar-carbon coated grids, rinsed on successive drops of 10 mmol/L TBS (Tris-buffered saline, 10 mmol/L Tris, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 5 mmol/L CaCl2 (Tris/CaCl2), and blocked with 0.1% BSA in Tris/CaCl2. The samples were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with 10 μg/mL prothrombin or 10 μg/mL factor X, thoroughly rinsed with Tris/CaCl2, and fixed with 0.1% glutaraldehyde in Tris/CaCl2. After rinsing on successive drops of TBS, PBS/0.02% glycine and PBS/1% BSA, immunogold labeling was performed as described above using rabbit polyclonal anti-prothrombin and rabbit polyclonal anti–factor X antibodies, followed by 10 nm protein-A gold.

RESULTS

Platelet releasates contain microvesicles and exosomes.

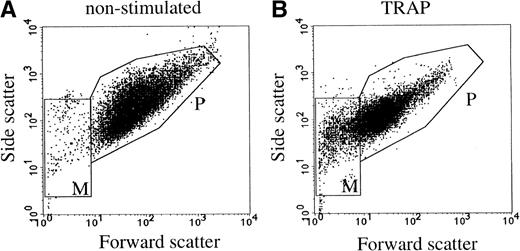

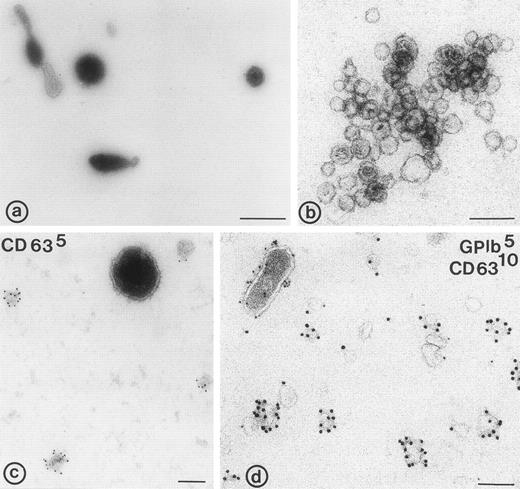

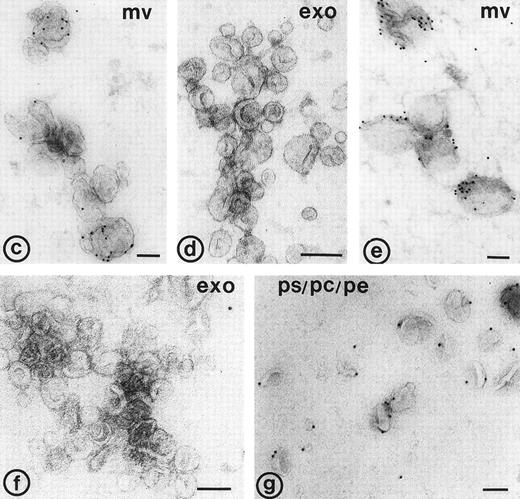

Flow cytometric analysis of washed platelets showed an increase in the mean fluorescence intensity after stimulation with 15 μmol/L TRAP, using anti–P-selectin and anti-CD63 antibodies (not shown). Thus, both markers were translocated from intracellular compartments to the cell surface. The flow cytometric scatter patterns show the formation of microvesicles in the lower lefthand gate of the scatter plot (M in Fig1B). To further investigate the release of membrane vesicles, the supernatant of platelets stimulated with 15 μmol/L TRAP was subjected to centrifugation at 10,000g. This 104-g fraction contained predominantly large membrane-bound vesicles (100 nm to 1 μm) with often an electron-dense cytoplasmic content (Fig 2a). By virtue of their size and morphology, these probably represent the population of vesicles that is formed by shedding from the cell surface, and which have been shown repeatedly by others using flow cytometry (microvesicles).3,4 The much smaller exosomes, analogous to those released by reticulocytes,19,30 and recently isolated from B cells,31 ie, the internal membrane vesicles of MVBs and α-granules in platelets, were rare in this fraction. To separate exosomes from soluble granule proteins, the supernatant of the 104-g fraction was subjected to centrifugation to equilibrium in a sucrose gradient, leaving the soluble proteins at the bottom of the gradient and membranes in the floating fractions. Whole-mount electron microscopy (EM) analysis showed that the fractions equilibrating at densities 1.14 to 1.18 g/mL were highly enriched in membrane-bound vesicles, ranging in size from 40 to 100 nm (Fig 2b), similar in size to those observed in MVBs and α-granules. A limited number of microvesicles was still present in this fraction (Fig2c and d). When the isolated exosome fraction was analyzed by flow cytometry, using biotinylated anti-CD63 antibody and streptavidine-FITC, the mean fluorescence intensity remained within background levels, indicating that the exosomes were too small to be detected by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric detection of platelets and microvesicles. Platelets were stimulated with 15 μmol/L TRAP. P and M indicate the gates for platelets and microvesicles, respectively. (A) Nonstimulated platelets; (B) TRAP-stimulated platelets. Data are shown of a representative single experiment.

Flow cytometric detection of platelets and microvesicles. Platelets were stimulated with 15 μmol/L TRAP. P and M indicate the gates for platelets and microvesicles, respectively. (A) Nonstimulated platelets; (B) TRAP-stimulated platelets. Data are shown of a representative single experiment.

Electron micrographs of 104-g fraction, and fractions from the sucrose gradient. (a) Plasma membrane-derived microvesicles; (b) exosomes; (c and d) microvesicles and exosomes. (c) Immunolabeling for CD63; note the difference in size between the CD63 positive exosomes and the microvesicle; (d) immuno-double labeling for GPIb and CD63; exosomes are enriched in CD63, while microvesicles (upper left in d) contain predominantly GPIb. Bars: (a) 500 nm; (b through d) 100 nm.

Electron micrographs of 104-g fraction, and fractions from the sucrose gradient. (a) Plasma membrane-derived microvesicles; (b) exosomes; (c and d) microvesicles and exosomes. (c) Immunolabeling for CD63; note the difference in size between the CD63 positive exosomes and the microvesicle; (d) immuno-double labeling for GPIb and CD63; exosomes are enriched in CD63, while microvesicles (upper left in d) contain predominantly GPIb. Bars: (a) 500 nm; (b through d) 100 nm.

Platelet exosomes are enriched in the tetraspan protein CD63.

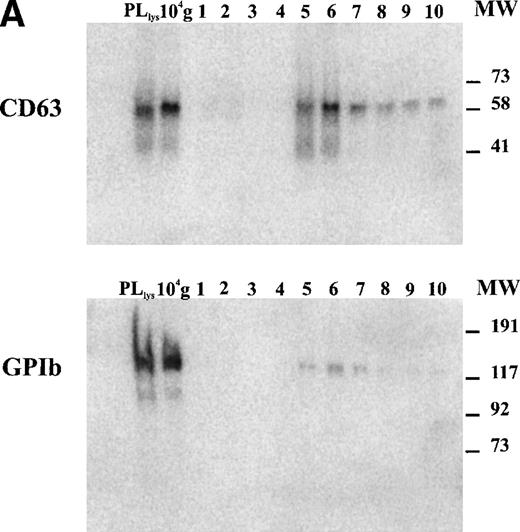

The tetraspan protein CD63, a marker for late endocytic compartments in many cell types and present in platelet lysosomes and dense granules, has recently been identified in multivesicular endocytic compartments and α-granules in platelets.24 GPIb, a plasma membrane marker, is absent from these organelles (Heijnen et al, unpublished observations, 1998). To analyze the presence of both markers on microvesicles and exosomes, equal aliquots of platelet lysate (PLlys), the 104-g fraction, and all fractions from the sucrose gradient were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using MoAbs AK-3 (GPIb) and CLB-Gran 1/2, 435 (CD63). As illustrated in Fig 3A, CD63 and GPIb were clearly detected in the PLlys and 104-g fraction (first two lanes), and were also present in fractions equilibrating at a density of ∼1.16 g/mL on the sucrose gradient (lanes 5 and 6). The amounts of GPIb and CD63 in these fractions were quite different. A relative enrichment for GPIb was found in the 104-g fraction, while CD63 was enriched in the fractions containing the exosomes (Fig3a).

Detection of CD63 and GPIb in platelet lysate, microvesicles, and exosomes. (A) Platelet releasates were centrifuged at 750g (PLlys) and 10,000g(104-g) after stimulation with 15 μmol/L TRAP. The exosome-enriched fraction was obtained after centrifugation of the supernatant at 65,000g. The membrane pellet was dissolved and then floated into a linear sucrose gradient. Top-bottom gradient fractions were diluted in SDS-sample buffer and analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of GPIb and CD63. (B) Relative distribution of CD63 and GPIb quantified from (A). CD63 is enriched in the fractions 5 and 6 from the sucrose gradient, equilibrating at density ∼1.16 g/mL. The majority of GPIb is recovered in PLlys, and the 104-g fraction and somewhat overlapping in the exosome fraction. PLlys, platelet pellet; 104-g, microvesicle fraction.

Detection of CD63 and GPIb in platelet lysate, microvesicles, and exosomes. (A) Platelet releasates were centrifuged at 750g (PLlys) and 10,000g(104-g) after stimulation with 15 μmol/L TRAP. The exosome-enriched fraction was obtained after centrifugation of the supernatant at 65,000g. The membrane pellet was dissolved and then floated into a linear sucrose gradient. Top-bottom gradient fractions were diluted in SDS-sample buffer and analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of GPIb and CD63. (B) Relative distribution of CD63 and GPIb quantified from (A). CD63 is enriched in the fractions 5 and 6 from the sucrose gradient, equilibrating at density ∼1.16 g/mL. The majority of GPIb is recovered in PLlys, and the 104-g fraction and somewhat overlapping in the exosome fraction. PLlys, platelet pellet; 104-g, microvesicle fraction.

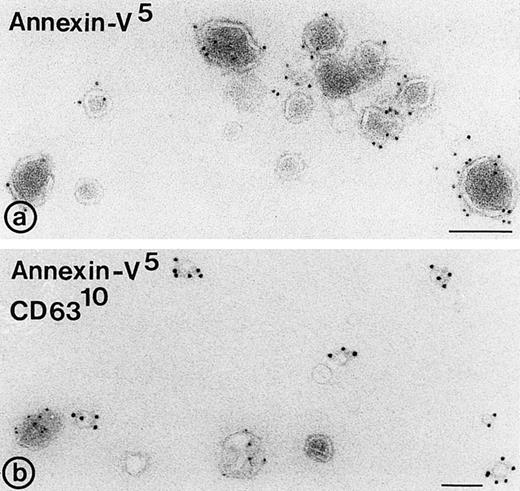

Binding of annexin-V, prothrombin, and factor X to isolated vesicle fractions. Microvesicles from the 10,000gfraction, exosomes from the sucrose gradient, and PS/PE/PC phopholipids were adsorbed to carbon-coated EM grids. The vesicles were incubated either with FITC-conjugated annexin-V, factor X, or prothrombin in the presence of 5 mmol/L CaCl2. After fixation, the membranes were immunolabeled with their respective antibodies and protein-A gold. (a) Annexin-V binding monitored with a polyclonal anti-FITC antibody and protein-A gold; (b) immunogold double labeling as indicated on the figure. Annexin-V binding is most prominent on the larger microvesicles. (c and d) Binding of prothrombin (c) and factor X (e) to microvesicles, but not to the exosomes (d and f); (g) binding of prothrombin to phospholipid vesicles. Bars: 100 nm.

Binding of annexin-V, prothrombin, and factor X to isolated vesicle fractions. Microvesicles from the 10,000gfraction, exosomes from the sucrose gradient, and PS/PE/PC phopholipids were adsorbed to carbon-coated EM grids. The vesicles were incubated either with FITC-conjugated annexin-V, factor X, or prothrombin in the presence of 5 mmol/L CaCl2. After fixation, the membranes were immunolabeled with their respective antibodies and protein-A gold. (a) Annexin-V binding monitored with a polyclonal anti-FITC antibody and protein-A gold; (b) immunogold double labeling as indicated on the figure. Annexin-V binding is most prominent on the larger microvesicles. (c and d) Binding of prothrombin (c) and factor X (e) to microvesicles, but not to the exosomes (d and f); (g) binding of prothrombin to phospholipid vesicles. Bars: 100 nm.

To further investigate the protein composition, whole-mount preparations of exosomes were immunolabeled with antibodies against CD63, GPIb, β1-integrin, Peta-3, P-selectin, and Pecam-1. These antibodies recognized the extracellular domains of these molecules, and were therefore suitable for whole-mount immunolabeling. CD63 appeared abundantly associated with the exosomes (Fig 2c and d). GPIb was only detected on the microvesicles (Fig 2d), together with Pecam-1, the platelet integrins αIIb-β3 and β1, and the two tetraspan proteins Peta-3 and CD9 (not shown). P-selectin was detected on a limited number of the exosomes as well (not shown). When the number of labeled and nonlabeled exosomes was determined, it appeared that about 50% or more of the exosomes were not labeled, depending on the antibody used. CD63 gave the highest percentage of labeled exosomes (∼50%), while Pecam-1, Peta-3, GPIb, and β1-integrin were hardly present on exosomes (Table1). Thus, while the composition of microvesicles reflects that of the platelet surface after activation, including that of P-selectin, exosomes are selectively enriched in CD63.

Distribution of Markers on Isolated Exosomes

| . | % Labeled Exosomes . |

|---|---|

| CD63 | 51.3 |

| GPIb | 13 |

| P-selectin | 29.1 |

| Peta-3 | 13.2 |

| Pecam-1 | 8.1 |

| CD29 | 6.2 |

| . | % Labeled Exosomes . |

|---|---|

| CD63 | 51.3 |

| GPIb | 13 |

| P-selectin | 29.1 |

| Peta-3 | 13.2 |

| Pecam-1 | 8.1 |

| CD29 | 6.2 |

The number of labeled exosomes was determined after immunolabeling as indicated. The figures are expressed as a percentage of the total number of exosomes counted. For each antibody at least 500 exosomes were evaluated.

Exosomes derive from exocytosis of MVBs and α-granules.

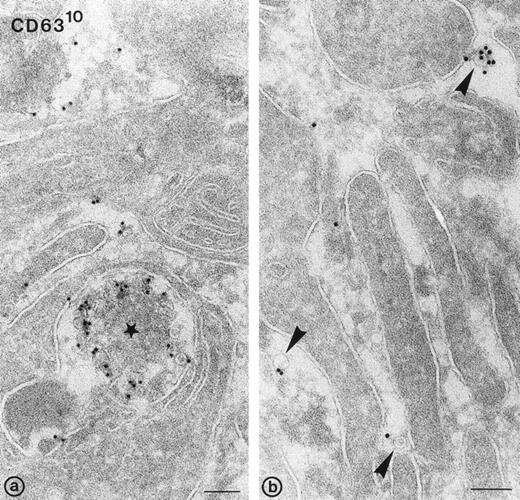

To investigate exosome release morphologically, washed platelets were stimulated at 37°C with 1 U/mL of α-thrombin, in the absence of dRGDW and EDTA. Under such conditions, a majority of the α-granules had fused with the platelet cell surface and open canalicular system (OCS). Figure 5a shows an exocytotic profile of an MVB with externalized CD63+vesicles (ie, exosomes). Exosomes were also found adjacent to the pseudopodal extensions formed during platelet aggregation (arrowheads in Fig 5b). The exosomes were similar in size to those previously described in multivesicular bodies and α-granules in nonstimulated platelets, and to those found in platelet releasates. Immunogold labeling for GPIb resulted in the specific labeling at the platelet cell surface, particularly on pseudopodal extensions, but not in labeling of exosomes (not shown). We conclude that the exosomes found in the platelet releasate after stimulation derive from exocytosis of multivesicular compartments and α-granules.

Release of exosomes from activated platelets. Thin frozen sections of a platelet aggregate after activation with 1 U/mL of -thrombin in the absence of dRGDW. Immunolabeling with anti-CD63 and protein-A gold (10 nm). (a) Exocytotic profile of multivesicular body containing CD63+ exosomes (star). (b) Exosomes detected in the extracellular area between platelet pseudopods (arrowheads). Bars: 100 nm.

Release of exosomes from activated platelets. Thin frozen sections of a platelet aggregate after activation with 1 U/mL of -thrombin in the absence of dRGDW. Immunolabeling with anti-CD63 and protein-A gold (10 nm). (a) Exocytotic profile of multivesicular body containing CD63+ exosomes (star). (b) Exosomes detected in the extracellular area between platelet pseudopods (arrowheads). Bars: 100 nm.

Exosomes do not bind annexin-V, prothrombin, and factor X.

To examine whether released exosomes also exhibit procoagulant sites like microvesicles, we studied first the exposure of anionic phospholipids on the isolated vesicle fractions. In the presence of low calcium concentrations, annexin-V binds specifically to areas in the membrane that are enriched in phosphatidylserine.11Isolated membrane fractions were adsorbed to carbon-coated grids and incubated with FITC-conjugated annexin-V in the presence of 5 mmol/L CaCl2. After fixation, the annexin-V binding to membranes was monitored by incubation with a polyclonal anti-FITC antibody and protein-A gold. Annexin-V bound predominantly to the microvesicles (Fig4a and b). Eighteen percent of the exosomes showed binding of annexin-V (Table 2), while no labeling was observed when vesicle fractions were incubated with polyclonal anti-FITC antibody and protein-A gold alone. To investigate the possibility that endogenous platelet annexin-V was already present on released exosomes, we incubated isolated exosome fractions with anti-annexin-V, followed by protein-A gold. No annexin-V was detected on the isolated exosomes.

Binding of Annexin-V, Factor X, and Prothrombin

| . | % Labeled Exosomes . |

|---|---|

| Annexin-V | 18 |

| Prothrombin | 4 |

| Factor X | 8 |

| . | % Labeled Exosomes . |

|---|---|

| Annexin-V | 18 |

| Prothrombin | 4 |

| Factor X | 8 |

Exosomes were incubated in the presence of 5 mmol/L CaCl2 with FITC-conjugated annexin-V, factor X, or prothrombin. Binding was monitored with the respective antibodies and protein-A gold (see Materials and Methods). The number of labeled exosomes is expressed as a percentage of 500 vesicles evaluated.

In a similar way, the binding of prothrombin and factor X to exosomes, microvesicles, and PS/PC/PE phospholipids was tested. The vesicles were adsorbed to carbon-coated grids and incubated with either prothrombin or factor X in the presence of 5 mmol/L CaCl2. Binding of both coagulation factors was monitored after fixation followed by incubation with their corresponding antibodies and protein-A gold. Less than 10% of the exosomes showed binding of prothrombin or factor X (Table 2, Fig 4d and f), while under similar conditions specific binding of prothrombin and factor X was observed to the population of large microvesicles (Fig 4c and e). A significant amount of the PS/PC/PE vesicles (>50%) showed also binding of prothrombin (Fig4g). No labeling was observed when vesicles were incubated with polyclonal anti-prothrombin or anti–factor X antibody alone.

DISCUSSION

We have studied the release of microvesicles and exosomes during platelet activation, using Western blotting and (immuno)-electron microscopical techniques. After stimulation with 15 μmol/L TRAP, relatively large vesicles were identified (microvesicles) together with a population of small vesicles (40 to 100 nm), showing similarities with the internal vesicles described previously in multivesicular bodies and α-granules.24 Analogous to the previously described vesicles released by reticulocytes and B cells,19 20 these small vesicles were termed exosomes. Western blot analysis of the membrane vesicles obtained from the releasate of activated platelets showed that the microvesicles contained predominantly plasma membrane glycoproteins, while the exosomes were selectively enriched in the late endocytic marker CD63. The selective enrichment of CD63 on exosomes was confirmed by immunogold labeling of isolated exosome fractions and of ultrathin cryosections of platelet aggregates. In situ CD63 was predominantly detected on released exosomes present in exocytotic profiles, and in between pseudopodal extensions. A limited number of the exosomes also contained P-selectin. Flow cytometric analysis after stimulation with 15 μmol/L TRAP showed that microvesicles are readily detected with anti-GPIb, but released exosomes were not observed using the anti-CD63 antibody.

In the present study we have also shown that exocytosis of multivesicular compartments and α-granules is accompanied by the release of exosomes, the former internal vesicles of MVBs and α-granules. These platelet exosomes contained CD63, in agreement with the enrichment of CD63 on the internal vesicle membranes. At present we do not know whether exocytosis of dense granules contributes as well to the release of CD63-enriched exosomes. Exocytosis of multivesicular endocytic compartments has been described in several cell types, particularly those of the hematopoietic lineage.19-21 The enrichment of certain molecules on exosomes suggests that such molecules are selectively sorted from other glycoproteins via the formation of small internal vesicles. Such a sorting in MVBs has been described for the transferrin receptor during reticulocyte maturation31 and in B cells for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules.32 Release of exosomes from these cells may serve a specialized function, respectively, in antigen presentation,20,22 and in the clearance of transferrin receptor during the maturation of reticulocytes into erythrocytes.33 In platelets, release of membrane vesicles has the potential to exert procoagulant activity at a distance from the site of platelet activation. However, we found that in the presence of 5 mmol/L CaCl2, binding sites for FITC-conjugated annexin-V were mainly presented on the large cell-surface–derived microvesicles, and not on exosomes. These observations suggest that microvesicles are enriched in aminophospholipids and, in addition to the platelet surface itself, are most likely the sites where procoagulant activity predominates. The relatively low number of exosomes that bound annexin-V suggests that the outer leaflet of platelet exosomes is probably not enriched in phosphatidylserine. This is in accord with previous findings in reticulocytes where exosomes have relatively high cholesterol content and only trace amounts of phosphatidylserine.34 Endogenous annexin-V was detected in the cytosol of resting and stimulated platelets (not shown), but was absent from small internal vesicles and isolated exosomes, suggesting that endogenous annexin-V is not associated with exosomes. Moreover, the finding that factor X and prothrombin readily bound to microvesicles but not to isolated exosomes under similar experimental conditions supports the concept that platelet exosomes are probably not the site where the prothrombinase complex is formed.

The selective enrichment of CD63 in platelet exosomes may provide a clue for their possible extracellular function. CD63 belongs to the family of tetraspan proteins, together with CD37, CD81, CD82, Peta-3, and CD9.35 The latter two are readily detected on the platelet cell surface after activation, including released microvesicles, but they were not enriched on exosomes. Several tetraspan proteins (CD37, CD81, CD82, and CD63) have recently been shown on the exosomes of human B lymphocytes.31 Besides CD63, none of them was detected on platelet exosomes. Tetraspan proteins may function cooperatively with each other36 in complex formation with cell surface proteins and can interact with integrins.37-39 Recent work has shown that CD9 is associated with β3-integrins in both resting and stimulated platelets.40,41 Formation of tetraspan-integrin complexes on the cell surface may also modulate integrins,42 and contribute to the signaling and adhesive functions of the integrin. For example, CD63 molecules have been implicated in the transmission of activation signals in neutrophils leading to increased adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial cells.43 The nature of the interactions between integrins and tetraspans is still unknown, but all these studies indicate that the extracellular domains of tetraspan proteins are involved. Platelet exosomes therefore may have the potential to excite signaling at a distance from the site of platelet activation. Such a signaling role may occur through specific association of CD63 with integrins on the cell surface of platelets (homotypic) or other cells (heterotypic) in the circulation.

In conclusion, we have found two populations of membrane vesicles that are released during platelet activation: platelet microvesicles and exosomes. The absence of factor X and prothrombin binding and the low capacity of annexin-V binding to exosomes suggest that the membranes of exosomes have little procoagulant activity. Whether CD63 on released exosomes serves another specific extracellular function, for example in transmission of activation signals to neutrophils44 or endothelial cells,45 remains to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Margot van Gastelen and Martijn van Andel for their excellent technical assistance, and Rene Scriwaneck for his help in preparing the electron micrographs. We are gratefully indebted to Drs J.M. Escola and W. Stoorvogel for their helpful suggestions during the course of this work.

Supported in part by the Netherlands Foundation of Thrombosis, Grant No. 97.003.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Harry F.G. Heijnen, PhD, Department of Hematology, G03.647, University Hospital Utrecht, PO Box 85500, NL-3508 GA Utrecht, The Netherlands; e-mail:H.F.G.Heijnen@lab.azu.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal