Abstract

Acquired mutations in the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR) occur in a subset of patients with severe congenital neutropenia (SCN) who develop acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). These mutations affect one allele and result in hyperproliferative responses to G-CSF, presumably through a dominant-negative mechanism. Here we show that a critical domain in the G-CSFR that mediates ligand internalization is deleted in mutant G-CSFR forms from patients with SCN/AML. Deletion of this domain results in impaired ligand internalization, defective receptor downmodulation, and enhanced growth signaling. These results explain the molecular basis for G-CSFR mutations in the pathogenesis of the dominant-negative phenotype and hypersensitivity to G-CSF in SCN/AML.

THE GRANULOCYTE colony-stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR) is a major regulator of in vivo granulopoiesis.1 Mice deficient in G-CSFR expression due to a targeted null mutation in the G-CSFR gene have chronic neutropenia and exhibit reduced numbers of marrow progenitors and impaired terminal granulocytic differentiation.2 These observations have led to speculation that defects in the G-CSFR may contribute to disorders of granulopoiesis.

The G-CSFR is a member of the Type-I cytokine receptor family and exists as a single-chain molecule that dimerizes on ligand binding to form high-affinity receptor complexes.3-5 Distinct functional domains have been identified in the cytoplasmic portion of the human G-CSFR.6 The membrane-proximal cytoplasmic region of 53 amino acids generates mitogenic signals, whereas the distal carboxy-terminal 98 amino acids are required for transduction of myeloid maturation signals.7-9

Acquired mutations in the G-CSFR gene have recently been reported in a subset of patients with severe congenital neutropenia (SCN) progressing to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).10-14 A direct relationship between the occurrence of these mutations and leukemic progression in patients with SCN has been suggested. These mutations localize to a critical region in the cytoplasmic domain spanning nts 2384-2429 and all have been nonsense mutations that introduce a premature stop codon leading to truncation of the distal cytoplasmic tail of the G-CSFR that is critical for maturation and growth arrest signaling. In the cases studied, the mutations have been found to affect cells of the myeloid lineage only. Both mutated and normal alleles of the G-CSFR are expressed in these patients. Interestingly, coexpression of wild-type (WT) and mutant G-CSFR forms in transfected myeloid cell lines to mimic the in vivo situation in patients with SCN/AML, interferes with terminal maturation by the WT receptor and leads to hyperproliferative responses to G-CSF through a presumed dominant-negative mechanism.8,10 11

The mechanisms promoting the dominant-negative phenotype in SCN/AML have remained elusive. Ligand binding in cells coexpressing both mutant and WT G-CSFR forms should induce mutant receptor homodimerization and mutant/WT receptor heterodimerization, as well as the formation of functionally active WT receptor homodimers. However, a defect in receptor processing or degradation leading to prolonged expression of mutant G-CSFR forms could lead to preferential formation of dimeric receptor complexes containing mutant receptor forms and produce a dominant-negative phenotype. To evaluate this possibility, we examined ligand internalization, receptor processing, and receptor degradation in cells expressing WT and mutant G-CSFR forms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Reagents for maintenance of cell lines were purchased from GIBCO-BRL (Grand Island, NY). [I125] G-CSF (>800 ci/mmol) and Pro-mix [35S] in vivo cell labeling mix (>1000 ci/mmol) were obtained from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL). [Methyl-3H] thymidine (82 ci/mmol) was from DuPont NEN (Wilmington, DE). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated.

DNA constructs.

For the construction of pCDM8-WT, the wild-type human Class-I G-CSFR cDNA (generously provided by Dr A. Larsen, Seattle, WA) was excised from pBluescript SK+, ligated to Bst XI linkers and inserted into the Bst XI site of pCDM8. The p309 plasmid containing the neomycin resistance gene was cotransfected with the G-CSFR cDNA plasmid to establish stable clones as previously described.15 The pCDM8 vector was a gift from Dr B. Seed (Cambridge, MA) and the p309 vector was generously provided by Dr J. Lang (Columbus, OH). The G-CSFR Δ716 clone was generated by introducing a stop codon with a C to T point mutation at nt 2384 of the WT cDNA by PCR. The oligonucleotides used to generate this mutant were: forward primer F1 (5′-CCACCTAGCCCCAATCCCAGTCTGGC-3′), and reverse R4 (5′-GATCGCTGGTGCCAGACTGGGATTGGGGCTAGG-3′); the underlined nucleotides indicate the position of the point mutations. In the first PCR reaction, primer F2 containing a 5′ restriction site for BamHI and corresponding to nts 2257-2273 of the WT cDNA was used in conjunction with the R4 primer. In the second PCR reaction, primer F1 was used with primer R2 that was designed to contain an XhoI restriction site and corresponded to nts 2584-2601 of the WT cDNA. The extension products from both reactions were ligated and further amplified using primers F2 and R2. The PCR fragment was subcloned into pBluescript SK+, excised from the plasmid by Cfr 10 I and Bst E II digestion, and ligated into the Cfr 10 I and Bst E II sites of pCDM8-WT. DNA sequencing was done to confirm the introduced point mutation.

Transfections and cell culture.

The pro-B Ba/F3 cell line was maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10% WEHI-3 conditioned media. Ba/F3 cells were stably transfected with the WT and Δ716 G-CSFR forms, as previously described.15 Clones were selected in G418-containing media. Neomycin-resistant clones were examined for binding of125I-G-CSF and the binding data analyzed by Scatchard analysis as previously described.15 Six WT and four Δ716 G-CSFR clones expressing similar receptor numbers and binding affinities were selected from a total of 32 and 11 clones, respectively, for use in all subsequent experiments. G-CSFR expression was confirmed by RT-PCR and DNA sequencing. COS-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and were transiently transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation of plasmid DNA.16 An equivalent amount of plasmid DNA was used for single transfections in COS-7 cells. A 1:1 molar ratio of pCDM8-WT and pCDM8-Δ716 was used for cotransfections in COS-7 cells.

Binding assays and competition studies.

Binding of [I125] G-CSF to transfected Ba/F3 cells was assayed as previously described.15 Binding of [I125] G-CSF to transfected COS-7 cells (plated at 5 × 104 cells/well ) was performed 72 hours after transfection of the cells in 12-well plates. Binding of [I125] G-CSF was examined in the absence and presence of varying concentrations of unlabeled G-CSF (0.1nmol/L to 1000nmol/L). Incubations were for 4 hours at 4°C, after which the cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed with 1 mol/L NaOH. Equivalent aliquots (400μL) from each well were counted in a gamma counter to determine bound [I125] G-CSF. Receptor numbers and binding affinities were calculated using the Ligand computer program.17 Percent competition was calculated as described by Dittrich et al.18 19

Proliferation studies.

Stably transfected Ba/F3 cells were serum and cytokine deprived for 2 to 4 hours in RPMI 1640, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2mmol/L glutamine. The cells were washed once in PBS and resuspended at 1 × 105/mL in RPMI 1640 media containing 10% FBS and 2mmol/L glutamine. A total of 5 × 103 cells/well were seeded in 96-well microtiter plates with varying concentrations of G-CSF (0.002-2000 pmol/L). Duplicate plates were also set up in the presence of IL-3 without G-CSF. The plates were incubated for a total of 72 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2, and pulsed with 0.5 μCi/well of [methyl-3H] thymidine for the last 8 hours of incubation. Samples were harvested onto glass fiber filters and counted in scintillation fluid.

Internalization studies.

Cells were incubated with 500pmol/L [I125] G-CSF for 2 hours at 4°C. Internalization was examined by temperature shifting to 37°C for varying times from 30 to 360 minutes. After incubation at 37°C, the cells were incubated for an additional 2 hours at 4°C. Unbound ligand was removed from the cells with cold PBS containing 1mmol/L MgCl2, 0.1mmol/L CaCl2, and 0.2% BSA. Surface-bound [I125] G-CSF was determined after the addition of 0.5 mol/L NaCl (pH1.0) for 3 minutes. The acid strip solution and wash were both collected to determine bound ligand. Internalized ligand was quantified by lysis of the cells with 1 mol/L NaOH for 1 minute. The data were expressed as percent receptor internalization over time.18 19

Receptor degradation.

Confluent monolayers of transfected COS-7 cells grown in T-75 flasks were incubated with short-term labeling media (RPMI 1640 media containing 10% dialyzed FBS without methionine and cysteine) for 15 minutes at 37°C to deplete intracellular pools of methionine and cysteine. The cells were then metabolically labeled with [35S] Cysteine/Methionine Pro-mix at 0.15mCi/mL in short-term labeling media for 1 hour at 37°C as previously described.18-20 The cells were washed with incubation media (RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 1 nmol/L G-CSF, and unlabeled methionine and cysteine) and incubated for varying times, then washed once in PBS, scraped, and pelleted. The cell pellets were lysed in buffer containing 1% NP-40 (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemical, Indianapolis, IN), 1 mmol/L EDTA (pH 8.0), 20 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.15 U/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 μg/mL pepstatin A, and 1 mmol/L sodium vanadate, then cleared of insoluble material. Lysates were precleared with protein A sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ), immunoprecipitated with 8 μg anti–G-CSFR antibody recognizing the N-terminal portion of the G-CSFR (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and analyzed under reducing conditions by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The gels were treated with Entensify (DuPont-NEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and dried. The labeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

RESULTS

Similar binding affinities of WT and mutant G-CSFR forms.

To study the role of the distal portion of the G-CSFR deleted in patients with AML preceded by SCN in the process of internalization, we constructed a deletion mutant designated Δ716 by introducing a premature stop codon through a C-to-T substitution at nt 2384 of the WT human (Class I) G-CSFR cDNA. This mutation deletes the most distal 98 carboxy-terminal amino acids of the G-CSFR and is the most frequent mutation that has been identified in patients with SCN/AML.10-14 Both the WT and Δ716 G-CSFR forms retain the conserved box 1 and box 2 regions that are essential for proliferation.

We initially examined the binding properties of the WT and Δ716 receptor forms stably transfected in Ba/F3 cells or transiently expressed in COS-7 cells. For COS-7 transfectants, studies were performed 3 days after the cells were transfected when receptor expression was maximal (data not shown). Cells were incubated with 500pmol/L [I125] G-CSF for 4 hours at 4°C in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabeled ligand. Scatchard analysis of the equilibrium-binding data showed expression of a single class of high-affinity receptors on the surface of both Ba/F3 and COS-7 transfected cells (data not shown). Δ716 receptors displayed similar binding affinities as the WT receptor. Dissociation constants for both G-CSFR forms were in the range of 4.2 to 61.0 × 10-11mol/L (Table 1). A 100-fold higher level of receptor expression was consistently observed in COS-7 cells making the COS-7 transfectants an ideal system for further studying receptor expression and processing. The reasons for the higher level of receptor expression on COS-7 cells are not clear, although other investigators have made similar observations with the G-CSFR and other cytokine receptors using COS-7 cells.4,18 21

Binding Properties of G-CSFR Transfectants

| G-CSFR . | Cell . | Kd (pM) . | Receptors/cell . |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Ba/F3 | 159 to 340 | 2.5 to 4.1 × 103 |

| COS-7 | 89 to 119 | 4.2 to 12.1 × 105 | |

| Δ716 | Ba/F3 | 75 to 606 | 4.6 to 16.4 × 103 |

| COS-7 | 42 to 91 | 2.2 to 15.9 × 105 |

| G-CSFR . | Cell . | Kd (pM) . | Receptors/cell . |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Ba/F3 | 159 to 340 | 2.5 to 4.1 × 103 |

| COS-7 | 89 to 119 | 4.2 to 12.1 × 105 | |

| Δ716 | Ba/F3 | 75 to 606 | 4.6 to 16.4 × 103 |

| COS-7 | 42 to 91 | 2.2 to 15.9 × 105 |

Scatchard analyses were performed on Ba/F3 and COS-7 cells transfected with either WT G-CSFR or Δ716 G-CSFR forms. Binding affinities and receptor numbers/cell are indicated. The data were generated from five independent experiments.

Hyperproliferative responses in cells expressing Δ716 receptors.

The mitogenic capacities of the WT and Δ716 G-CSFR forms in response to G-CSF were examined in stably transfected Ba/F3 cells (Fig 1). Ba/F3 cells transfected with either the WT or the Δ716 mutant responded to G-CSF in a dose-dependent fashion. Notably, the Δ716 transfectants responded to a 100-fold lower concentration of G-CSF than WT transfectants. The shift to the left in the dose-response curve for Δ716 transfectants indicates that cells expressing this receptor form are hypersensitive to G-CSF, an observation also reported by other investigators.8 10

Proliferative responses of G-CSFR transfectants. Ba/F3 cells stably transfected with the WT or Δ716 G-CSFR were serum and cytokine deprived for 4 hours before cytokine stimulation. Cell proliferation was assayed in the presence of G-CSF or IL-3. The data are expressed as the percent [methyl-3H] thymidine uptake in cells grown in G-CSF versus maximal growth in IL-3 containing media. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Proliferative responses of G-CSFR transfectants. Ba/F3 cells stably transfected with the WT or Δ716 G-CSFR were serum and cytokine deprived for 4 hours before cytokine stimulation. Cell proliferation was assayed in the presence of G-CSF or IL-3. The data are expressed as the percent [methyl-3H] thymidine uptake in cells grown in G-CSF versus maximal growth in IL-3 containing media. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent experiments.

An internalization domain in the distal region of the G-CSFR is deleted in the Δ716 receptor.

We next examined ligand internalization over time in COS-7 and Ba/F3 cells transfected with the WT receptor alone or the Δ716 receptor alone. Because G-CSFR mutations in patients with SCN/AML affect only one allele, we also examined ligand internalization in cells expressing both the WT and Δ716 receptors (WT/Δ716 ) to mimic the in vivo situation. Cells were incubated with 500 pmol/L [I125] G-CSF for 2 hours at 4°C. The temperature was shifted to 37°C for different times after which the cells were returned to ice for another 2 hours. Surface-bound G-CSF was eluted by high salt/low pH incubation for 3 minutes, and internalized G-CSF was determined after solubilization of the cells in 1mol/L NaOH.

As shown in Fig 2, internalization of G-CSF in COS-7 cells was apparent within 30 minutes in WT transfectants, and by 2 hours surface binding was nearly undetectable indicating rapid downregulation of WT receptors (left panel). However, ligand internalization was delayed in Δ716 transfectants and significant amounts of surface binding of G-CSF could still be detected at 6 hours (middle panel). The detection of persistent surface binding beyond 2 hours suggests a defect in receptor downregulation in Δ716 transfectants. Nearly identical results as observed with Δ716 transfectants were obtained with COS-7 cells coexpressing both the WT and Δ716 receptors (WT/Δ716), as would be expected if the Δ716 mutant conferred a dominant-negative phenotype. Ligand internalization was also examined in Ba/F3 transfectants and similar results were obtained as observed with COS-7 transfectants (data not shown).

Internalization of surface-bound [125I] G-CSF by WT and mutant ▵716 G-CSFR complexes. Three days after transfection COS-7 cells were washed, incubated with 500 pmol/L [125I]-G-CSF for 2 hours at 4°C, then shifted to 37°C for the indicated times. Cells were returned to ice again for 2 hours, then washed to eliminate unbound ligand. Surface-bound ligand (▪) was determined after acid stripping in 0.5 mol/L NaCl/HCl (pH1.0) for 3 minutes. Internalized ligand (○) was measured after lysis of the cells in 1 mol/L NaOH. Data are expressed as a percentage of initial binding of G-CSF at 4°C. Values represent the mean of duplicate points. The data shown are from three independent experiments. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars.

Internalization of surface-bound [125I] G-CSF by WT and mutant ▵716 G-CSFR complexes. Three days after transfection COS-7 cells were washed, incubated with 500 pmol/L [125I]-G-CSF for 2 hours at 4°C, then shifted to 37°C for the indicated times. Cells were returned to ice again for 2 hours, then washed to eliminate unbound ligand. Surface-bound ligand (▪) was determined after acid stripping in 0.5 mol/L NaCl/HCl (pH1.0) for 3 minutes. Internalized ligand (○) was measured after lysis of the cells in 1 mol/L NaOH. Data are expressed as a percentage of initial binding of G-CSF at 4°C. Values represent the mean of duplicate points. The data shown are from three independent experiments. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars.

Delayed degradation of the Δ716 receptor.

To determine whether altered receptor degradation could account for the defects observed in receptor modulation in Δ716 transfectants, we examined receptor processing and degradation in pulse-chase experiments with COS-7 transfectants. Three days after transfection, COS-7 cells expressing either the WT or Δ716 receptors alone, or coexpressing both the WT and Δ716 receptor forms (WT/Δ716) were metabolically labeled with [35S] methionine and [35S] cysteine for 1 hour. The cells were then chased with 1 nmol/L G-CSF in DMEM containing unlabeled methionine and cysteine for 0 to 8 hours. The cells were lysed, immunoprecipitated with an antibody recognizing the amino-terminus of the G-CSFR, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. In all of the transfectants an upward shift in molecular weight of the receptor was observed by 1 hour. This suggests that the receptor is glycosylated to a more mature form of 150 kD for the WT receptor and 127 kD for the truncated Δ716 receptor (Fig 3A). In the presence of G-CSF, the mature WT receptor (left panel, arrow) was largely degraded by 4 hours. In contrast, even at 8 hours there was little evidence of degradation of the mature Δ716 receptor (middle panel), consistent with delayed receptor degradation in cells expressing the mutant Δ716 G-CSFR form. In COS-7 cells coexpressing both receptor forms (WT/Δ716), degradation of each receptor form was similar to that observed in corresponding single transfectants (right panel). To account for the differences in intensity of labeled bands between blots, the blots were individually subjected to densitometry with standardization at time 0 and the fold-change in intensity calculated (Fig 3B). Densitometric analysis further confirmed delayed receptor degradation in Δ716 transfectants.

G-CSF stimulated degradation of the wild-type (WT) and ▵716 mutant G-CSFR. (A) Confluent monolayers of COS-7 cells, transfected with the wild-type (WT) G-CSFR alone, mutant ▵716 receptor alone, or cotransfected with both the WT and ▵716 receptors (WT/▵716), were incubated for 1 hour in DMEM containing [35S] methionine and [35S] cysteine. Thereafter, the cells were incubated in DMEM containing 1nmol/L G-CSF and unlabeled methionine and cysteine for 0 to 8 hours. The cells were lysed, immunoprecipitated with antibody to the aminoterminus of the G-CSFR, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. Both receptor forms are glycosylated to more mature forms (arrows). (B) The autoradiographs from (A) were analyzed by densitometry. Data are expressed as the fold-change compared to time 0.

G-CSF stimulated degradation of the wild-type (WT) and ▵716 mutant G-CSFR. (A) Confluent monolayers of COS-7 cells, transfected with the wild-type (WT) G-CSFR alone, mutant ▵716 receptor alone, or cotransfected with both the WT and ▵716 receptors (WT/▵716), were incubated for 1 hour in DMEM containing [35S] methionine and [35S] cysteine. Thereafter, the cells were incubated in DMEM containing 1nmol/L G-CSF and unlabeled methionine and cysteine for 0 to 8 hours. The cells were lysed, immunoprecipitated with antibody to the aminoterminus of the G-CSFR, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. Both receptor forms are glycosylated to more mature forms (arrows). (B) The autoradiographs from (A) were analyzed by densitometry. Data are expressed as the fold-change compared to time 0.

DISCUSSION

SCN or Kostmann’s syndrome is a disorder of granulopoiesis characterized by an absolute neutrophil count of 200 to 500/μL, a maturation arrest of neutrophil precursors in the bone marrow at the promyelocyte/myelocyte stage of differentiation, and frequent severe bacterial infections.22,23 The disease may be inherited in an autosomal recessive manner or occur sporadically. In the majority of patients with SCN, treatment with pharmacologic doses of G-CSF improves peripheral neutrophil counts and reduces infection-related events.24,25 However, approximately 10% to 15% of patients with SCN develop AML.13 14

The molecular mechanisms underlying SCN remain unknown. Defects in G-CSF production or G-CSFR expression do not appear to play a role in the pathogenesis of SCN. Serum G-CSF levels are usually high in patients with SCN and G-CSFR numbers are normal to increased with normal binding affinities.26-29 Despite elevated serum G-CSF levels in most patients with SCN, pharmacologic doses of G-CSF generally restore in vivo granulopoiesis.24,28 GM-CSF treatment, however, is usually ineffective.30 These observations have led to the suggestion that a defect in G-CSFR signal transduction may be involved in the pathogenesis of SCN.

In the subset of patients with SCN progressing to AML, acquired mutations in the G-CSFR have been detected in the patients examined. These mutations affect one allele and delete the maturation signaling domain of the G-CSFR.11-14 Enforced expression of these mutations in myeloid cell lines in vitro7,8 and in cells from knock-in mice in vivo results in increased sensitivity to G-CSF through a dominant-negative mechanism. Both the number and size of colonies grown in the presence of G-CSF have been found to be increased in knock-in mice in colony-forming assays.31 32 These observations have led to the hypothesis that G-CSFR mutations are involved in the pathogenesis of AML arising from SCN.

We considered the possibility that cells from patients with SCN/AML may have a defect in processing or degradation of the G-CSFR leading to the dominant-negative phenotype. Aberrant receptor processing has been shown to play a role in the pathophysiology of several human diseases including Laron dwarfism, type-A insulin resistance, and familial hypercholesterolemia.33-35 Mutations in the erythropoietin receptor, another member of the cytokine receptor superfamily, have recently been identified in patients with familial polycythemia, and these mutations confer a dominant-negative phenotype.36

We show that ligand internalization and downmodulation of receptor expression are defective in cells coexpressing WT and mutant G-CSFR forms as observed in patients with SCN/AML. Delayed receptor degradation results in prolonged expression of mutant G-CSFR forms and the formation of dimeric receptor complexes containing mutant receptors. Enhanced expression of mutant receptor complexes leads to the dominant-negative phenotype.

A role for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) in ligand internalization and receptor downmodulation was recently reported for receptors for CSF-1 and PDGF. Attenuated rates of internalization and degradation were observed with CSF-1 and PDGF receptor mutants that failed to bind PI3-K.37,38 In the case of the G-CSFR, we have previously shown that activation of PI3-K requires the region spanning residues 682 to 716. We showed that Δ716 cells could activate PI3-K in response to G-CSF stimulation.39 Thus, similar to the Flt3/Flk2 receptor, PI3-K does not appear to be required for internalization and downmodulation of the G-CSFR.40

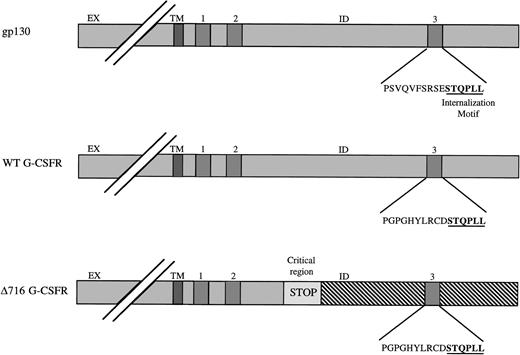

A dileucine motif corresponding to the amino acid sequence STQPLL was previously identified in the box 3 region of gp130 and was shown to mediate interleukin-6 (IL-6) internalization and downregulation of the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R).18,19 41 An identical dileucine motif is present in the distal tail of the WT G-CSFR but is deleted in G-CSFR forms from patients with SCN/AML such as the Δ716 mutant (Fig 4). Because the G-CSFR shows significant homology to gp130 and contains the identical dileucine motif in its conserved box 3 region, we speculate that this motif also mediates internalization of G-CSF and modulates receptor expression. Additional studies are in progress to directly test the role of the dileucine motif in ligand internalization and receptor modulation using G-CSFR forms with targeted mutations in the dileucine motif.

Schematic diagram of dileucine internalization motif. The extracellular (EX), transmembrane (TM) and intracellular (ID) domains are indicated for gp130 and the wild-type (WT) and mutant ▵716 G-CSFR forms. A dileucine motif (underlined) that modulates ligand internalization and receptor expression localizes to the distal region of box 3 in gp130. An identical motif is present in the WT G-CSFR (underlined). Mutations in the critical region in patients with SCN/AML as in the ▵716 mutation result in the introduction of a premature stop codon (STOP) and deletion of the carboxy-terminal tail of the G-CSFR (diagonal lines) within which lies the dileucine motif (underlined).

Schematic diagram of dileucine internalization motif. The extracellular (EX), transmembrane (TM) and intracellular (ID) domains are indicated for gp130 and the wild-type (WT) and mutant ▵716 G-CSFR forms. A dileucine motif (underlined) that modulates ligand internalization and receptor expression localizes to the distal region of box 3 in gp130. An identical motif is present in the WT G-CSFR (underlined). Mutations in the critical region in patients with SCN/AML as in the ▵716 mutation result in the introduction of a premature stop codon (STOP) and deletion of the carboxy-terminal tail of the G-CSFR (diagonal lines) within which lies the dileucine motif (underlined).

We are investigating the specific signaling molecules affected to explain the hyperproliferative response observed with Δ716 cells. We recently showed that the distal tail of the G-CSFR that is deleted in Δ716 mutants is required for recruitment of the negative growth regulator SH2-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP).39 Recruitment of SHIP was found to correlate with decreased proliferative responses. Thus, loss of the domain required for SHIP recruitment and downregulation of proliferative responses seems a likely explanation for the enhanced growth of Δ716 cells.

Mutant receptor forms from patients with SCN/AML also delete the maturation signaling domain. These receptors fail to generate differentiation signals but transduce proliferation signals that are enhanced. Expression of mutant G-CSFR forms in myeloid progenitors could increase their self-renewal capacity and predispose to leukemia. Additionally, high-dose G-CSF therapy as used in patients with SCN could further promote expansion of abnormal clones harboring G-CSFR mutations.

Our results provide an explanation for the dominant-negative phenotype observed in SCN/AML and suggest a mechanism by which G-CSFR mutations result in hypersensitivity to G-CSF. Because the majority of patients with SCN are treated with G-CSF, continued close monitoring including molecular studies for G-CSFR mutations will be necessary to determine whether chronic administration of G-CSF alters the latency or incidence of AML in these patients.

Supported by NCI Grant No. CA75226.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

![Fig. 1. Proliferative responses of G-CSFR transfectants. Ba/F3 cells stably transfected with the WT or Δ716 G-CSFR were serum and cytokine deprived for 4 hours before cytokine stimulation. Cell proliferation was assayed in the presence of G-CSF or IL-3. The data are expressed as the percent [methyl-3H] thymidine uptake in cells grown in G-CSF versus maximal growth in IL-3 containing media. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/2/10.1182_blood.v93.2.440/4/m_blod40223001x.jpeg?Expires=1765893485&Signature=STVvnJtosspcCY9XbmswQgW8wXUU006KIoQKWpgp4X7UrjdTVg~yT3-P4QtVWv7JmvZCGrVHK6wivaaYlSY9xRW2KUfPvirXIQnFOG058EIpw0x5gqrrAjCbglTjnUWWxn9s4DwdH8Pv9QrohTUw1uW1D91Hq5w5XeySmSyb~EmovcGYd6cOKPdINu4xwaTURxDTr2sloOhnn9MyBM4cnuF4WMTWToT~KgoulNnOflvx7eQDcslzVRi1eIQpibgPNb0k7vjy872ubRrmunxx93MKAVMpvP0jBBV9Mhj85b-4nGC6bs4SpEay737r2i4myfhWRIXTc9od4IqTFznDkg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 2. Internalization of surface-bound [125I] G-CSF by WT and mutant ▵716 G-CSFR complexes. Three days after transfection COS-7 cells were washed, incubated with 500 pmol/L [125I]-G-CSF for 2 hours at 4°C, then shifted to 37°C for the indicated times. Cells were returned to ice again for 2 hours, then washed to eliminate unbound ligand. Surface-bound ligand (▪) was determined after acid stripping in 0.5 mol/L NaCl/HCl (pH1.0) for 3 minutes. Internalized ligand (○) was measured after lysis of the cells in 1 mol/L NaOH. Data are expressed as a percentage of initial binding of G-CSF at 4°C. Values represent the mean of duplicate points. The data shown are from three independent experiments. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/2/10.1182_blood.v93.2.440/4/m_blod40223002x.jpeg?Expires=1765893485&Signature=VbnjBDDuGFJNLOCmwVZ5p5Q58upOtHKffOiMAVLsP09wyN0a2DxBZ8l0ovL6vuCcdzEkSDZjV~6OddkgNBCSBnAcdypniwEN6pqEJHyidgUs~ZNd48gq1PVcBsl7aYhdcYZFevLFDzQi2zL01iAGrcPvNYXkzOkRiIgkXPYz1wZh1XGZYQmWYsVSljGQwZy9B3rz6J6TZWQPBgl2V8Q1b8pBtfLr~kgIrfE9TDAIcQxRmGWsUFqED8OzlCczLUKqB24PDDDU0~Jm9DnbBNR0whHG8zfWPrpTifudTdjSNnFC5znZrJZ-5QZJC5gSNIX1ewdhlsW6AEDjCt87BAH6zg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 3. G-CSF stimulated degradation of the wild-type (WT) and ▵716 mutant G-CSFR. (A) Confluent monolayers of COS-7 cells, transfected with the wild-type (WT) G-CSFR alone, mutant ▵716 receptor alone, or cotransfected with both the WT and ▵716 receptors (WT/▵716), were incubated for 1 hour in DMEM containing [35S] methionine and [35S] cysteine. Thereafter, the cells were incubated in DMEM containing 1nmol/L G-CSF and unlabeled methionine and cysteine for 0 to 8 hours. The cells were lysed, immunoprecipitated with antibody to the aminoterminus of the G-CSFR, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. Both receptor forms are glycosylated to more mature forms (arrows). (B) The autoradiographs from (A) were analyzed by densitometry. Data are expressed as the fold-change compared to time 0.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/2/10.1182_blood.v93.2.440/4/m_blod40223003w.jpeg?Expires=1765893485&Signature=Fk9eAcVdjEPdM7azHan6hGJFCX8~T1sjZmx~HFltpIdjGPr0wY8VTN7heP9NFkF82XVyZ1pB-nyZxSPdEdJHzLCx02P6JAq-0fjlK5bbcpKmZFXej625zZsghDs3Z8B-mItcNbAIMln6r-AQi~YmLuhKFafZiiAHfXYbMSrV8igbS0Q7NSOdep61WnY0xnnWSt3bkFg6~Lo-c4gxQOHliJTEnEu0~C2r56Eb-92BzXelOGEbx9IFYsCPxOI-TKLRUoIov0RLkwjyRLuCcRGE4PSUbklK8dp4nzXir1URIPP-x3iRPfV4mpnOCup59isFt-T9LKfH4XB-3FljBvuK8w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal