Abstract

A Rhesus D (RhD) red blood cell phenotype with a weak expression of the D antigen occurs in 0.2% to 1% of whites and is called weak D, formerly Du. Red blood cells of weak D phenotype have a much reduced number of presumably complete D antigens that were repeatedly reported to carry the amino acid sequence of the regular RhD protein. The molecular cause of weak D was unknown. To evaluate the molecular cause of weak D, we devised a method to sequence all 10RHD exons. Among weak D samples, we found a total of 16 different molecular weak D types plus two alleles characteristic of partial D. The amino acid substitutions of weak D types were located in intracellular and transmembraneous protein segments and clustered in four regions of the protein (amino acid positions 2 to 13, around 149, 179 to 225, and 267 to 397). Based on sequencing, polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism and polymerase chain reaction using sequence-specific priming, none of 161 weak D samples investigated showed a normal RHD exon sequence. We concluded, that in contrast to the current published dogma most, if not all, weak D phenotypes carry altered RhD proteins, suggesting a causal relationship. Our results showed means to specifically detect and to classify weak D. The genotyping of weak D may guide Rhesus negative transfusion policy for such molecular weak D types that were prone to develop anti-D.

THE RHESUS D (RhD) antigen (ISBT 004.001; RH1) carried by the RhD protein is the most important blood group antigen determined by a protein. It is still the leading cause of hemolytic disease of the newborn.1 About 0.2% to 1% of whites have red blood cells with a reduced expression of the D antigen (weak D, formerly Du).2-4 A small fraction of weak D samples are explained by qualitatively altered RhD proteins, called partial D,5 and frequently caused byRHD/RHCE hybrid alleles, a flurry of which was recently published (reviewed in Huang6). Another fraction is caused by the suppressive effects of Cde haplotypes in trans position.7 These weak D likely possess the normalRHD allele, because the carriers’ parents and children often express a normal RhD antigen density. Such weak D show only a minor reduction of RhD antigen expression, were loosely called high grade Du, and often typed today as normal RhD, because of the increased sensitivity of monoclonal anti-D.8

The majority of weak D phenotypes is caused by genotype(s) located either at the Rhesus genes’ locus itself or in its proximity, because the weak D expression is inherited along with the RhD phenotype.2 Besides the mere quantitative reduction, no qualitative differences could be discerned in the RhD antigen of this group. Two recent studies addressed the molecular cause of the prevalent weak D phenotypes. Both groups, Rouillac et al9and Beckers et al,10 performed reverse-transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and claimed unanimously that their sequencing of RHD cDNA in weak D samples showed a normal RHD coding sequence. However, no definite molecular cause of the weak D expression was established and the proposed mechanisms differed. Using semiquantitative RT-PCR, Rouillac et al9 reported reduced steady-state levels of RHDtranscripts and claimed that their observations provided direct evidence of a quantitative difference in RhD between normal and weak D red blood cells. In contrast, Beckers et al10,11 found no differences in the amounts of RHD transcripts, further excluded an excess of splice variants,10 12 and concluded that weak D is not caused by regulatory defects of the transcription process.

Screening of random weak D samples by PCR for RHD specific polymorphisms confirmed PCR amplification patterns representative for a normal RHD allele.13,14 However, evidence was accumulating that the underlying molecular basis can be heterogeneous,13 and some weak D may carry structurally abnormal RHD alleles. In four of 44 English weak D, noRHD specific intron 4 PCR amplicons13 were detected, and in one of 90 Northern German weak D, no RHDspecific exon 5 PCR amplicons14 were detected. In a similar more extensive molecular screen by PCR-SSP,15 we found about 2.5% structural abnormalities in more than 600 weak D samples (Gassner et al, manuscript submitted).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood samples.

Sequencing of the 10 RHD exons from genomic DNA.

DNA was prepared as described previously.15 Nucleotide sequencing was performed with a DNA sequencing unit (Prism dye terminator cycle-sequencing kit with AmpliTaq FS DNA polymerase; ABI 373A, Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany). Nucleotide sequencing of genomic DNA stretches representative for all 10 RHD exons and parts of the promoter was accomplished using primers (Table 1) and amplification procedures (Table 2) that obviated the need for subcloning steps.

Primers Used

| Name . | Nucleotide Sequence . | Genomic Region . | Position* . | Orientation . | RHD-Specific . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ra21 | gtgccacttgacttgggact | Intron 2 | 2,823 to 2,842 | Sense | No |

| rb7 | atctctccaagcagacccagcaagc | Exon 7 | 1,022 to 998 | Antisense | No |

| rb11 | tacctttgaattaagcacttcacag | Intron 4 | 161 to 185 | Sense | Yes |

| rb12 | tcctgaacctgctctgtgaagtgc | Intron 4 | 198 to 175 | Antisense | Yes |

| rb13 | ctagagccaaacccacatctcctt | Promoter | −675 to −652 | Sense | No |

| rb15 | ttattggctacttggtgcc | Intron 5 | −612 to −630 | Antisense | No |

| rb20d | tcctggctctccctctct | Intron 2 | −25 to −8 | Sense | Yes |

| rb21 | aggtccctcctccagcac | Intron 3 | 28 to 11 | Antisense | No |

| rb21d | cccaggtccctcctcccagcac | Intron 3 | 32 to 11 | Antisense | No |

| rb22 | gggagattttttcagccag | Intron 4 | 82 to 64 | Antisense | No |

| rb24 | agacctttggagcaggagtg | Intron 4 | −53 to −34 | Sense | No |

| rb25 | agcagggaggatgttacag | Intron 5 | −111 to −93 | Sense | No |

| rb26 | aggggtgggtagggaatatg | Intron 6 | −62 to −43 | Sense | No |

| rb44 | gcttgaaatagaagggaaatgggagg | Intron 7 | ≈3,000 | Antisense | No |

| rb46 | tggcaagaacctggaccttgacttt | Intron 3 | −1,279 to −1,255 | Sense | No |

| rb52 | ccaggttgttaagcattgctgtacc | Intron 7 | ≈−3,300 | Sense | Yes |

| re01 | atagagaggccagcacaa | Promoter | −149 to −132 | Sense | Yes |

| re02 | tgtaactatgaggagtcag | Promoter | −572 to −554 | Sense | Yes |

| re11d | agaagatgggggaatctttttcct | Intron 1 | 129 to 106 | Antisense | No |

| re12d | attagccgggcacggtggca | Intron 1 | −1,188 to −1,168 | Sense | Yes |

| re13 | actctaatttcataccaccc | Intron 1 | −72 to −53 | Sense | No |

| re23 | aaaggatgcaggaggaatgtaggc | Intron 2 | 251 to 227 | Antisense | No |

| re31 | tgatgaccatcctcaggt | Exon 3 | 472 to 455 | Antisense | Yes |

| re617 | tctcagctcactgcaacctc | Intron 6 | 1,998 to 2,017 | Sense | No |

| re621 | catccccctttggtggcc | Intron 6 | −102 to −85 | Sense | Yes |

| re71 | acccagcaagctgaagttgtagcc | Exon 7 | 1,008 to 985 | Antisense | Yes |

| re73 | cctttttgtccctgatgacc | Intron 7 | −67 to −48 | Sense | No |

| re74 | tatccatgaggtgctgggaac | Intron 7 | ≈−200 | Sense | No |

| re75 | aaggtaggggctggacag | Intron 7 | ≈120 | Antisense | Yes |

| re82 | aaaaatcctgtgctccaaac | Intron 8 | ≈−45 | Sense | Yes |

| re83 | gagattaaaaatcctgtgctcca | Intron 8 | ≈−50 | Sense | No |

| re91 | caagagatcaagccaaaatcagt | Intron 9 | ≈−40 | Sense | No |

| re93 | cacccgcatgtcagactatttggc | Intron 9 | ≈300 | Antisense | No |

| rf51 | caaaaacccattcttcccg | Intron 5 | −332 to −314 | Sense | No |

| rg62 | tgtattccaggcagaaggc | Intron 6 | 1,736 to 1,755 | Sense | No |

| rh5 | gcacagagacggacacag | 5′ UTR† | −19 to −2 | Sense | No |

| rh7 | acgtacaaatgcaggcaac | 3′ UTR | 1,330 to 1,313 | Antisense | No |

| rr1 | tgttggagagaggggtgatg | 5′ UTR | −60 to −41 | Sense | No |

| rr3 | cagtctgttgtttaccagatg | 3′ UTR | 1,512 to 1,492 | Antisense | Yes |

| rr4 | agcttactggatgaccacca | 3′ UTR | 1,541 to 1,522 | Antisense | Yes |

| Name . | Nucleotide Sequence . | Genomic Region . | Position* . | Orientation . | RHD-Specific . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ra21 | gtgccacttgacttgggact | Intron 2 | 2,823 to 2,842 | Sense | No |

| rb7 | atctctccaagcagacccagcaagc | Exon 7 | 1,022 to 998 | Antisense | No |

| rb11 | tacctttgaattaagcacttcacag | Intron 4 | 161 to 185 | Sense | Yes |

| rb12 | tcctgaacctgctctgtgaagtgc | Intron 4 | 198 to 175 | Antisense | Yes |

| rb13 | ctagagccaaacccacatctcctt | Promoter | −675 to −652 | Sense | No |

| rb15 | ttattggctacttggtgcc | Intron 5 | −612 to −630 | Antisense | No |

| rb20d | tcctggctctccctctct | Intron 2 | −25 to −8 | Sense | Yes |

| rb21 | aggtccctcctccagcac | Intron 3 | 28 to 11 | Antisense | No |

| rb21d | cccaggtccctcctcccagcac | Intron 3 | 32 to 11 | Antisense | No |

| rb22 | gggagattttttcagccag | Intron 4 | 82 to 64 | Antisense | No |

| rb24 | agacctttggagcaggagtg | Intron 4 | −53 to −34 | Sense | No |

| rb25 | agcagggaggatgttacag | Intron 5 | −111 to −93 | Sense | No |

| rb26 | aggggtgggtagggaatatg | Intron 6 | −62 to −43 | Sense | No |

| rb44 | gcttgaaatagaagggaaatgggagg | Intron 7 | ≈3,000 | Antisense | No |

| rb46 | tggcaagaacctggaccttgacttt | Intron 3 | −1,279 to −1,255 | Sense | No |

| rb52 | ccaggttgttaagcattgctgtacc | Intron 7 | ≈−3,300 | Sense | Yes |

| re01 | atagagaggccagcacaa | Promoter | −149 to −132 | Sense | Yes |

| re02 | tgtaactatgaggagtcag | Promoter | −572 to −554 | Sense | Yes |

| re11d | agaagatgggggaatctttttcct | Intron 1 | 129 to 106 | Antisense | No |

| re12d | attagccgggcacggtggca | Intron 1 | −1,188 to −1,168 | Sense | Yes |

| re13 | actctaatttcataccaccc | Intron 1 | −72 to −53 | Sense | No |

| re23 | aaaggatgcaggaggaatgtaggc | Intron 2 | 251 to 227 | Antisense | No |

| re31 | tgatgaccatcctcaggt | Exon 3 | 472 to 455 | Antisense | Yes |

| re617 | tctcagctcactgcaacctc | Intron 6 | 1,998 to 2,017 | Sense | No |

| re621 | catccccctttggtggcc | Intron 6 | −102 to −85 | Sense | Yes |

| re71 | acccagcaagctgaagttgtagcc | Exon 7 | 1,008 to 985 | Antisense | Yes |

| re73 | cctttttgtccctgatgacc | Intron 7 | −67 to −48 | Sense | No |

| re74 | tatccatgaggtgctgggaac | Intron 7 | ≈−200 | Sense | No |

| re75 | aaggtaggggctggacag | Intron 7 | ≈120 | Antisense | Yes |

| re82 | aaaaatcctgtgctccaaac | Intron 8 | ≈−45 | Sense | Yes |

| re83 | gagattaaaaatcctgtgctcca | Intron 8 | ≈−50 | Sense | No |

| re91 | caagagatcaagccaaaatcagt | Intron 9 | ≈−40 | Sense | No |

| re93 | cacccgcatgtcagactatttggc | Intron 9 | ≈300 | Antisense | No |

| rf51 | caaaaacccattcttcccg | Intron 5 | −332 to −314 | Sense | No |

| rg62 | tgtattccaggcagaaggc | Intron 6 | 1,736 to 1,755 | Sense | No |

| rh5 | gcacagagacggacacag | 5′ UTR† | −19 to −2 | Sense | No |

| rh7 | acgtacaaatgcaggcaac | 3′ UTR | 1,330 to 1,313 | Antisense | No |

| rr1 | tgttggagagaggggtgatg | 5′ UTR | −60 to −41 | Sense | No |

| rr3 | cagtctgttgtttaccagatg | 3′ UTR | 1,512 to 1,492 | Antisense | Yes |

| rr4 | agcttactggatgaccacca | 3′ UTR | 1,541 to 1,522 | Antisense | Yes |

The positions of the synthetic oligonucleotides are indicated relative to their distances from the first nucleotide position of the start codon ATG for all primers in the promoter and in the exons, or relative to their adjacent exon/intron boundaries for all other primers. Primers ra2160 and rh561 were reported previously.

5′ UTR: 5′ untranslated region of exon 1; 3′ UTR: 3′ untranslated region of exon 10.

Sequencing Method for all 10 RHD Exons From Genomic DNA

| RHD Exon . | PCR Primers . | RHD-Specific* . | PCR Conditions† . | Sequencing Primers . | RHD-Specific* . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense . | Antisense . | Extension . | Annealing . | ||||

| Exon 1 | rb13 | rb11d | No | 10 min | 60°C | re01 | Yes |

| Exon 2 | re12d | re23 | Yes | 3 min | 65°C | re13 | No |

| Exon 3 | ra21 | rb21 | No | 10 min | 60°C | re31 and rb20d | Yes |

| Exon 4 | rb46 | rb12 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | rb22 | No |

| Exon 5 | rb11 | rh2 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | rb24 | No |

| Exon 6 | rf51 | re71 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | rb25 | No |

| Exon 7 | re617 | rb44 | No | 10 min | 60°C | re621 and re75 | Yes |

| Exon 8 | rb52 | rb93 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | re73 | No |

| Exon 9 | rb52 | rb93 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | re82/re83 | Yes/no |

| Exon 10 | re91 | rr4 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | rr3/rh7 | Yes/no |

| RHD Exon . | PCR Primers . | RHD-Specific* . | PCR Conditions† . | Sequencing Primers . | RHD-Specific* . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense . | Antisense . | Extension . | Annealing . | ||||

| Exon 1 | rb13 | rb11d | No | 10 min | 60°C | re01 | Yes |

| Exon 2 | re12d | re23 | Yes | 3 min | 65°C | re13 | No |

| Exon 3 | ra21 | rb21 | No | 10 min | 60°C | re31 and rb20d | Yes |

| Exon 4 | rb46 | rb12 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | rb22 | No |

| Exon 5 | rb11 | rh2 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | rb24 | No |

| Exon 6 | rf51 | re71 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | rb25 | No |

| Exon 7 | re617 | rb44 | No | 10 min | 60°C | re621 and re75 | Yes |

| Exon 8 | rb52 | rb93 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | re73 | No |

| Exon 9 | rb52 | rb93 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | re82/re83 | Yes/no |

| Exon 10 | re91 | rr4 | Yes | 10 min | 60°C | rr3/rh7 | Yes/no |

To achieve RHD specificity for genomic nucleotide sequencing, the PCR primer pairs or the sequencing primer or both must not concurrently detect RHCE-derived nucleotide sequences. Primer sequences are given in Table 1.

Primers were used at a concentration of 1 nmol/L in the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). In the exon 10 PCR, the concentration of MgCl2 was 2.0 nmol/L. Denaturation was 20 seconds at 92°C, annealing 30 seconds, elongation temperature 68°C. Elongation time was increased by 20 seconds for each cycle after the 10th cycle, except for the re12d/re23 primer pair.

Control of RHD specificity.

RHD exons 3 to 7 and 9 carry at least one RHD-specific nucleotide, which was used to verify the RHD origin of the sequences. For exon 1, characteristic nucleotides in the adjacent parts of intron 1 were used.21 For exon 8, the RHDspecificity of the PCR amplification was checked by RHDnonspecific sequencing of the informative exon 9, because exons 8 and 9 were amplified as a single PCR amplicon (Table 2). Exon 2 and 10 were amplified in an RHD- specific way (Table 2) based on publishedRHD-specific nucleotide sequences (EMBL nucleotide sequence data base accession numbers U66340 and U66341)22,23; no PCR amplicons were obtained in RhD− controls (data not shown). All normal D and weak D samples showed a G at position 65424 and a C at position 1036,22 supporting the notion25 that the alternatively described C22 and T,24 respectively, were sequencing errors.

Detection of weak D specific mutations by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and PCR using sequence-specific priming (PCR-SSP).

PCR-RFLP methods were developed to characterize distinct nucleotide substitutions detected in five RHD alleles: the C to G substitution at position 8 led to the loss of a Sac I restriction site in amplicons obtained with re01 and re11d (G to A at 29, loss of Msp I site, re01/re11d; C to A at 446, loss ofAlu I site, rb20d/rb21d; T to G at 809, loss of Alw44 I site, rf51/re71; G to C at 1154, introduction of Alu I site, re82/re93). Conditions for the rf51/re71 PCR reaction were as shown in Table 2. The rb20d/rb21d reaction was done with nonproofreading Taq-polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany or Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with 20 seconds denaturation at 94°C, 30 seconds annealing at 60°C, and 30 seconds extension at 72°C. The other PCR reactions were performed with nonproofreading Taq-polymerase with 20 seconds denaturation at 94°C, 30 seconds annealing at 55°C, and 1 minute extension at 72°C.

Another four RHD alleles were detected by a standard RHPCR-SSP15: the RHD(T201R,F223V) andRHD(S182T,K198N,T201R) alleles lacked specific amplicons for RHD exon 4, the RHD(G307R) and RHD(A276P) alleles lacked those for RHD exon 6. For all other weak D types, the authenticity of the point mutations was checked by nucleotide sequencing of independent PCR amplicons.

Sequencing of the RHD promoter.

To check for mutations in the RHD promoter, we amplified a 675-bp region using primer pair rb13 and rb11d (Table 2). The promoter region was sequenced using primers re02 and re01 starting at nucleotide position −545 relative to the first nucleotide of the start codon.

Characterization of RHD allele polymorphisms in introns 3 and 6.

In RHD intron 3, there was a G/C polymorphism that determined aHae III-RFLP at position −371 relative to the intron 3/exon 4 junction. To check this polymorphism, we amplified the 3′ part of intron 3 using the RHD specific primer pair rb46 and rb12 and digested the PCR products with Hae III. InRHD intron 6, there was a variable length TATT tandem repeat starting 1,915 bp 3′ of exon 6. To examine this tandem repeat, we amplified the full-length intron 6 using the RHD-specific primer pair rf51 and re71 and used primer rg62 for sequencing. The haplotype association of the Hae III site was tested in 10 CCDee, 8 ccDEE, 10 ccDee (W16C+), and 10 ccDee (W16C−) samples. The haplotype association of the TATT repeat was tested in 3 CCDee, 3 ccDEE, 1ccDEe, 2 ccDee (W16C+), and 2 ccDee (W16C−) samples. In control samples, the presence and absence of the Hae III site was linked to 9 and 8 TATT repeats, respectively. The Hae III site was present in the 20 CDe haplotypes and 18 of 20 cDe haplotypes tested, but absent in 15 of 16 cDE haplotypes (CDe v cDE,P < .001; cDe v cDE, P < .001; CDev cDe, not significant; 2 × 2 contingency tables, Fisher’s exact test).

Sequencing of intron 5 and exons 6 to 9 in DIV type III.

In DIV type III exons 6 to 9 were amplified and sequenced using primers that were specific for RHCE andRHD. Therefore, primer re71 was substituted by primer rb7; primer re621 by rb26; and primer re52 by re74. To demonstrate anRHD-RHCE hybrid allele, we amplified intron 5 in aRHD-specific way using the exon 5 PCR reaction (Table 2) and sequenced the breakpoint region using primer rb15.

cDNA sequencing.

RNA was prepared and reverse-transcribed as published.21cDNA was amplified in a nested PCR reaction (High Fidelity PCR system, Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) with external primers RR1 and RR4 and internal primers Rh5 and RR3 and subcloned into pMos (pMos-T-kit; United States Biochemical, Cleveland, OH).

Expected proportion of silent mutations.

In the 416 codons of the RHD gene excluding the start codon, 2,766 missense and 919 silent mutations can occur yielding an expected proportion of 0.254 of silent mutations. A total of 782 of the missense mutations and 437 of the silent mutations are transitions resulting in an expected proportion of 0.36 of silent transitions. A total of 41 missense and 30 silent mutations are located in CpG doublets resulting in a proportion of silent mutations in CpG doublets of 0.42. Independent of any possible excess of transitions or mutations in CpG doublets, random nucleotide changes should therefore lead to a minimal frequency of silent mutations of 0.254. Nonsense mutations and mutations in the start codon were assumed to prevent RhD expression13 and are excluded from the calculations.

Population frequency and haplotype association of weak D types.

The phenotype frequencies of weak D types among weak D samples were calculated separately for each serologic (CcDEe) weak D phenotype and combined according to the frequencies of the serologic weak D phenotypes.3 ccDEE weak D samples were assumed to be cDE/cdE. Phenotype frequencies in the population were calculated from the population frequency of the weak D phenotype in Southwestern Germany.3 These data are minimal estimates, because some samples with only moderately weakened D expression may have been inadvertantly grouped to normal strength D. Haplotype frequencies were calculated using a haplotype frequency of 0.411 for RhD− haplotypes3 assuming that all weak D samples were heterozygous. For weak D types 1 to 5, 9, 13, and 15, more than one proband was observed rendering the haplotype association trivial. Weak D type 11 was observed in a ccDee phenotype implying a cDe haplotype. Weak D types 6 to 8 and 12 were observed in single CcDee samples and assumed to be CDe/cde, which is correct in more than 96% of samples according to the haplotype frequencies in the population investigated.3 Weak D types 10, 14, and 16 were observed in single ccDEe samples and assumed to be cDE/cde, which is correct in more than 98% of samples.3 Hence, the probability that an cDE versus cDe misassignment corrupted the analysis of haplotype-specific polymorphisms was less than 0.05.

RhD topology prediction.

The position of the transmembraneous helices was based on an analysis of RhD by the PredictProtein server prediction of transmembrane helices (http://www.embl-heidelberg.de/predictprotein/predictprotein.html,26helix 1 to 11) and TMpred (http://ulrec3.unil.ch/software/TMPRED_form.html,27 helix 12) with minor modifications localizing position 110 and 226 on the cell surface and 12 in the membrane in accordance with other published models.28,29 There is experimental evidence30 31 for intracellular positions of the amino and carboxytermini.

RESULTS

Coding sequence of RHD in weak D phenotypes.

A method for RHD-specific sequencing of the 10 RHDexons and their splice sites was developed. In a sequential analysis strategy, blood samples with weak expression of antigen D, including a random survey of 161 samples from blood donors in Southwestern Germany, were checked by this method, PCR-RFLP (Fig1), and RHD PCR-SSP.15 We found 18 RHDalleles with distinct nucleotide changes coding for amino acid substitutions (Table 3). One allele lackedRHD exons 6 to 9 concordant with a RHD-CE-D hybrid allele dubbed hereby DIV type III. Another allele was DHMi.32 Of the remaining 16 alleles, 14 showed single, but distinct previously unknown missense mutations. None of the encoded variant amino acids occurred at the corresponding positions in the RhCE proteins. Two alleles exhibited multiple nucleotide changes typical for the RHCE gene, which were interspersed byRHD-specific sequences.

Detection of weak D types by PCR-RFLP. Four weak D types harbored point mutations that obliterated restriction sites: weak D type 1 lacks an Alw44 I site (A); weak D type 3, a SacI site (C); weak D type 5, an Alu I site (D); and weak D type 6, a Msp I site (E). In a fifth weak D type, a point mutation introduced a restriction site: weak D type 2 gained an Alu I site (B). On the left side of the gels, 100 bp ladders are shown; the position of the 500 bp and 100 bp fragments are indicated on the right side of the panels. For the PCR reaction of (A), the largest restriction fragment approximation 3,000 bp is not shown.

Detection of weak D types by PCR-RFLP. Four weak D types harbored point mutations that obliterated restriction sites: weak D type 1 lacks an Alw44 I site (A); weak D type 3, a SacI site (C); weak D type 5, an Alu I site (D); and weak D type 6, a Msp I site (E). In a fifth weak D type, a point mutation introduced a restriction site: weak D type 2 gained an Alu I site (B). On the left side of the gels, 100 bp ladders are shown; the position of the 500 bp and 100 bp fragments are indicated on the right side of the panels. For the PCR reaction of (A), the largest restriction fragment approximation 3,000 bp is not shown.

Proposed Nomenclature, Molecular Basis and Minimal Population Frequencies of RHD Alleles Coding for Weak D Phenotypes

| Trivial Name . | Molecular Basis (allele) . | Nucleotide Change . | Protein Sequence . | Exon . | Membrane Localization3-150 . | CpG3-151 . | Population Study . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.3-152 . | % of Weak D . | Phenotype Frequency (%) . | Haplotype Frequency . | |||||||

| Weak D type 1 | RHD (V270G) | T → G at 809 | Val to Gly at 270 | 6 | TM | No | 95 | 70.29 | 0.2964 | 1:277 |

| Weak D type 2 | RHD (G385A) | G → C at 1154 | Gly to Ala at 385 | 9 | TM | No | 43 | 18.01 | 0.0759 | 1:1,082 |

| Weak D type 3 | RHD (S3C) | C → G at 8 | Ser to Cys at 3 | 1 | IC | No | 7 | 5.19 | 0.0219 | 1:3,759 |

| Weak D type 4 | RHD (T201R, F223V) | C → G at 602, T → G at 667, G → A at 819 | Thr to Arg at 201 Phe to Val at 223 no change | 4 5 6 | IC TM — | NA3-153 NA Yes | 6 | 1.30 | 0.0055 | 1:14,925 |

| Weak D type 5 | RHD (A149D) | C → A at 446 | Ala to Asp at 149 | 3 | TM | No | 2 | 0.84 | 0.0035 | 1:23,256 |

| Weak D type 6 | RHD (R10Q) | G → A at 29 | Arg to Gln at 10 | 1 | IC | Yes | 1 | 0.74 | 0.0031 | 1:26,316 |

| Weak D type 7 | RHD (G339E) | G → A at 1016 | Gly to Glu at 339 | 7 | TM | No | 1 | 0.74 | 0.0031 | 1:26,316 |

| Weak D type 8 | RHD (G307R) | G → A at 919 | Gly to Arg at 307 | 6 | IC | Yes | 1 | 0.74 | 0.0031 | 1:26,316 |

| Weak D type 9 | RHD (A294P) | G → C at 880 | Ala to Pro at 294 | 6 | TM | No | 1 | 0.42 | 0.0017 | 1:47,619 |

| Weak D type 10 | RHD (W393R) | T → C at 1177 | Trp to Arg at 393 | 9 | IC | No | 1 | 0.42 | 0.0017 | 1:47,619 |

| Weak D type 11 | RHD (M295I) | G → T at 885 | Met to Ile at 295 | 6 | TM | No | 1 | 0.22 | 0.0009 | 1:90,909 |

| Weak D type 12 | RHD(G277E) | G → A at 830 | Gly to Glu at 277 | 6 | TM | No | 0 | <2.223-155 | ||

| Weak D type 13 | RHD (A276P) | G → C at 826 | Ala to Pro at 276 | 6 | TM | No | 0 | <2.223-155 | ||

| Weak D type 14 | RHD (S182T, K198N, T201R) | T → A at 544, A → T at 594, C → G at 602 | Ser to Thr at 182 Lys to Asn at 198 Thr to Arg at 201 | 4 4 4 | TM IC IC | NA NA NA | 0 | <2.223-155 | ||

| Weak D type 15 | RHD (G282D) | G → A at 845 | Gly to Asp at 282 | 6 | TM | No | 0 | <1.263-155 | ||

| Weak D type 16 | RHD (W220R) | T → C at 658 | Trp to Arg at 220 | 5 | TM | No | 0 | <1.263-155 | ||

| DIV type III3-154 | RHD-CE(6-9)-D | multiple | multiple | 6 to 9 | EF/TM/IC | NA | 1 | 0.60 | 0.0025 | 1:32,448 |

| DHMi | RHD (T283I) | C → T at 848 | Thr to Ile at 283 | 6 | EF | No | 1 | 0.42 | 0.0017 | 1:47,619 |

| Trivial Name . | Molecular Basis (allele) . | Nucleotide Change . | Protein Sequence . | Exon . | Membrane Localization3-150 . | CpG3-151 . | Population Study . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.3-152 . | % of Weak D . | Phenotype Frequency (%) . | Haplotype Frequency . | |||||||

| Weak D type 1 | RHD (V270G) | T → G at 809 | Val to Gly at 270 | 6 | TM | No | 95 | 70.29 | 0.2964 | 1:277 |

| Weak D type 2 | RHD (G385A) | G → C at 1154 | Gly to Ala at 385 | 9 | TM | No | 43 | 18.01 | 0.0759 | 1:1,082 |

| Weak D type 3 | RHD (S3C) | C → G at 8 | Ser to Cys at 3 | 1 | IC | No | 7 | 5.19 | 0.0219 | 1:3,759 |

| Weak D type 4 | RHD (T201R, F223V) | C → G at 602, T → G at 667, G → A at 819 | Thr to Arg at 201 Phe to Val at 223 no change | 4 5 6 | IC TM — | NA3-153 NA Yes | 6 | 1.30 | 0.0055 | 1:14,925 |

| Weak D type 5 | RHD (A149D) | C → A at 446 | Ala to Asp at 149 | 3 | TM | No | 2 | 0.84 | 0.0035 | 1:23,256 |

| Weak D type 6 | RHD (R10Q) | G → A at 29 | Arg to Gln at 10 | 1 | IC | Yes | 1 | 0.74 | 0.0031 | 1:26,316 |

| Weak D type 7 | RHD (G339E) | G → A at 1016 | Gly to Glu at 339 | 7 | TM | No | 1 | 0.74 | 0.0031 | 1:26,316 |

| Weak D type 8 | RHD (G307R) | G → A at 919 | Gly to Arg at 307 | 6 | IC | Yes | 1 | 0.74 | 0.0031 | 1:26,316 |

| Weak D type 9 | RHD (A294P) | G → C at 880 | Ala to Pro at 294 | 6 | TM | No | 1 | 0.42 | 0.0017 | 1:47,619 |

| Weak D type 10 | RHD (W393R) | T → C at 1177 | Trp to Arg at 393 | 9 | IC | No | 1 | 0.42 | 0.0017 | 1:47,619 |

| Weak D type 11 | RHD (M295I) | G → T at 885 | Met to Ile at 295 | 6 | TM | No | 1 | 0.22 | 0.0009 | 1:90,909 |

| Weak D type 12 | RHD(G277E) | G → A at 830 | Gly to Glu at 277 | 6 | TM | No | 0 | <2.223-155 | ||

| Weak D type 13 | RHD (A276P) | G → C at 826 | Ala to Pro at 276 | 6 | TM | No | 0 | <2.223-155 | ||

| Weak D type 14 | RHD (S182T, K198N, T201R) | T → A at 544, A → T at 594, C → G at 602 | Ser to Thr at 182 Lys to Asn at 198 Thr to Arg at 201 | 4 4 4 | TM IC IC | NA NA NA | 0 | <2.223-155 | ||

| Weak D type 15 | RHD (G282D) | G → A at 845 | Gly to Asp at 282 | 6 | TM | No | 0 | <1.263-155 | ||

| Weak D type 16 | RHD (W220R) | T → C at 658 | Trp to Arg at 220 | 5 | TM | No | 0 | <1.263-155 | ||

| DIV type III3-154 | RHD-CE(6-9)-D | multiple | multiple | 6 to 9 | EF/TM/IC | NA | 1 | 0.60 | 0.0025 | 1:32,448 |

| DHMi | RHD (T283I) | C → T at 848 | Thr to Ile at 283 | 6 | EF | No | 1 | 0.42 | 0.0017 | 1:47,619 |

IC, intracellular; TM, transmembraneous; EF, exofacial.

Mutation occurring in CpG doublet.

Number of samples (no.) observed among 161 random blood samples with weak antigen D expression. Types 12 to 16 were detected in additional weak D samples.

Not applicable, substitution(s) probably derived from gene conversion.

Upper limit of 95% confidence interval (Poisson distribution).

In the D IV type III allele, the presence of aRHCE-RHD hybrid was proven by RHD-specific sequencing of the 5′ breakpoint region. This breakpoint was located in intron 5 between −993 bp and −814 bp relative to the first nucleotide of exon 6 (range of 180 bp; Genbank accession numbers Z97333 andZ97364).

Distribution of weak D alleles in whites.

A set of 161 samples with weak expression of antigen D was gathered from random blood donors in Southwestern Germany. D category VI samples, but no other partial D, were excluded by serologic methods. Two samples represented known partial D (DHMi32 and D category IV33). Without any exception, all samples could be assigned to distinct RHD alleles with aberrant RHD exon sequences (Table 3). We propose that the new molecular weak D types should be referred to by trivial names, eg, weak D type 1, or by their molecular structures, eg, RHD(V270G). The weak D type 1 was the most frequent known RHD allele (f = 1:277) with aberrant coding sequence, exceeding even the DVII allele frequency.34

Amino acid substitutions in weak D alleles are clustered.

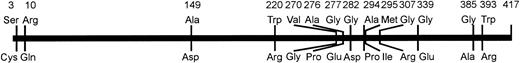

The amino acid substitutions observed in weak D types with single missense mutations were not evenly distributed in the RhD protein (Fig 2). The majority of substitutions occurred in the region of amino acid positions 267 to 397. Single and multiple amino acid substitutions in smaller portions of the RhD protein around positions 2 to 13, 149, and 179 to 225 (weak D type 4 and 14) were also found in weak D alleles. According to the current RhD loop model, the involved amino acids were positioned in the transmembraneous and intracellular protein segments (Fig 3).

Schematic representation of the amino acid variations observed in weak D types with single missense mutations. The affected amino acids of the prevalent normal RhD protein and their positions are shown on top. Their substitutions occurring in the weak D types are shown below the bar. The distribution of the variant positions deviated from the uniform distribution (P < .05, Kolmogoroff-Smirnov-test).

Schematic representation of the amino acid variations observed in weak D types with single missense mutations. The affected amino acids of the prevalent normal RhD protein and their positions are shown on top. Their substitutions occurring in the weak D types are shown below the bar. The distribution of the variant positions deviated from the uniform distribution (P < .05, Kolmogoroff-Smirnov-test).

Localization of the amino acid substitutions of the weak D types. A predicted topology of the RhD protein with respect to the plane of the red blood cells’ membrane is presented. Amino acid substitutions are shown for single events (black circles) and multiple events (gray circles). The amino acid substitutions of all weak D types were located in intracellular and transmembraneous protein segments.

Localization of the amino acid substitutions of the weak D types. A predicted topology of the RhD protein with respect to the plane of the red blood cells’ membrane is presented. Amino acid substitutions are shown for single events (black circles) and multiple events (gray circles). The amino acid substitutions of all weak D types were located in intracellular and transmembraneous protein segments.

Normal RhD phenotype controls and RHD promoter.

RHD specific sequencing of the 10 RHD exons predicted regular RhD protein sequences in six control samples with a normal antigen D expression; 545 bp 5′ of the start codon comprising part of the RHD promoter were sequenced in one sample of each weak D type, DHMi, and DIV type III. No deviation from the normal RHD promoter sequence35 was found.

Statistical evidence that missense mutations can cause weak D phenotypes.

The frequency of altered RhD proteins in weak D (159 of 159) and normal D samples (0 of 6) was statistically significantly different (P< .0001, 2 × 2 contingency table, Fisher’s exact test). A normal RhD coding sequence in the weak D phenotype was expected to occur in less than 1.9% (upper limit of 95% confidence interval, Poisson distribution). These amino acid substitutions are unlikely to reflect random nucleotide changes, because a random mechanism would lead to a frequency of silent mutations of at least 0.254, while we observed only one silent mutation among a total of 18 mutations in weak D alleles (P = .037, binomial distribution).

Haplotype-specific RHD polymorphisms.

In intron 3 and intron 6, we detected polymorphic RHD sequences that differed between the prevalent RHD alleles of the CDe and cDE haplotypes (Table 4). Weak D alleles were identical to the prevalent alleles of the same RHhaplotype in regard to these polymorphisms, with the single exception of weak D type 4 displaying a unique intron 6 repeat sequence. The conservation of these haplotype-specific RHD polymorphisms suggested that weak D alleles evolved independently.

RHD Polymorphisms in Weak D Types of VariousRH Haplotypes

| Haplotype . | Allele . | Hae III Site in Intron 3 . | TATT-Repeat in Intron 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDe | Prevalent RHD | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 1 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 3 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 6 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 7 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 8 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 12 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 13 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | DIV type III | Present | —4-150 |

| cDE | Prevalent RHD | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 2 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 5 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 9 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 10 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 14 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 15 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 16 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | DHMi | Absent | 8 |

| cDe | Prevalent RHD | Present | 9 |

| cDe | Weak D type 4 | Present | 13 |

| cDe | Weak D type 11 | Present | 9 |

| Haplotype . | Allele . | Hae III Site in Intron 3 . | TATT-Repeat in Intron 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDe | Prevalent RHD | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 1 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 3 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 6 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 7 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 8 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 12 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | Weak D type 13 | Present | 9 |

| CDe | DIV type III | Present | —4-150 |

| cDE | Prevalent RHD | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 2 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 5 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 9 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 10 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 14 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 15 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | Weak D type 16 | Absent | 8 |

| cDE | DHMi | Absent | 8 |

| cDe | Prevalent RHD | Present | 9 |

| cDe | Weak D type 4 | Present | 13 |

| cDe | Weak D type 11 | Present | 9 |

Intron 6 derived from RHCE due to a gene conversion.

DISCUSSION

The weak D phenotype is represented by a group ofRHD+ genotypes that code in their vast majority for altered RhD proteins associated with a reduced RhD expression on the red blood cells’ surface. Our population-based study dismissed unequivocally the possibility of one distinct antigen Duand showed in contrast to previous conjectures, that weak D alleles do generally possess mutations in RHD exon sequences. We provided statistical evidence that the missense mutations observed in the alleles of all weak D types are the probable cause for the reduced antigen D expression.

We suggest a causal relation of missense mutations and reduced RhD protein integration: (1) weak D alleles evolved independently in the different haplotypes, each distinct event being associated with a change in the RhD protein sequence; (2) no sample occurred with a normal RHD sequence despite observation of 13 different alleles in 161 samples; (3) type and distribution of the observed nucleotide substitutions was not compatible with the null hypothesis of random changes; (4) missense mutations causing reduced RhD expression fit nicely into the current model of RhD membrane integration.

Rh proteins occur in a complex with the Rh50 protein, and the expression of the Rh/Rh50 complex depends on the presence of both intact Rh5036 and Rh37,38 proteins. Missense mutations in the Rh50 protein are known to cause reduced expression of the Rh complex.36,39 Amino acid substitutions in the RhD protein might hence affect the expression of the RhD/Rh50 complex. A formal experimental proof of causality would involve expression systems. The only currently available system40 has, so far, not been shown to predict expression in a quantitative way.

Based on the distribution and kind of amino acid substitutions, a general picture of the relationship of RhD structure and RhD expression arose: all amino acid substitutions in weak D were located in the intracellular or transmembraneous parts of the RhD protein. Known RhD alleles with exofacial substitutions32,41-43 were discovered by virtue of their partial D antigen, but may display discrete (DNU and DVII) to moderate (DII, DHR, and DHMi) reductions in RhD expression.43-45 Most substitutions reported in this study were nonconservative and the introduced amino acids, in particular proline, likely disrupted the secondary or tertiary structure. Two weak D alleles (type 2 and 11) were associated with conservative substitutions indicating that the involved amino acid regions at positions 295 and 385 may be particularly important for an optimal RhD membrane integration. In two alleles (type 4 and type 14), parts of exon 4 and 5 were substituted by the corresponding parts of the RHCE gene. Similar exchanges occurred in DVI type I and DVI type II that exhibited a considerably reduced RhD protein expression45 also. Previous paradoxical observations can be explained, if the N152T substitution in exon 3 is considered to facilitate the membrane integration: (1) DIIIa,46 differing from weak D type 4 by the N152T substitution only, has a normal RhD antigen density,45 and (2) DIIIc, DIVa, and DVI type III harboring the N152T substitution have enhanced antigen densities21 45 compared with their appropriate controls (normal RhD and DVI type II).

Our genomic sequencing method was optimized to detect missense mutations. The approach obviated the laborious need to obtain full-length cDNA and to differentiate missense mutations from misincorporated nucleotides introduced during PCR and subcloning steps. The demonstration of missense mutations by genomic RHDsequencing definitively refuted the current dogma9,10 of a normal RHD allele in weak D phenotypes. The possibility of additional aberrations, eg, multiple hybrid genes with complementaryRHD exon patterns, was formally excluded for the most frequent weak D type 1 representing about 0.3% of all RHD alleles by sequencing the full-length cDNA. Our results are incongruous with two earlier reports asserting normal RHD coding sequences in three weak D samples from France9 and in an unspecified number of weak D samples from the Netherlands.10 Possibly, these investigators missed the mutations because of technical problems of the traditional approach based on cDNA. Alternative explanations are very unlikely: (1) There might be regional variations in the causes of weak D, although other Rh alleles as frequent as the prevalent weak D alleles do not differ much in whites. (2) Both groups may have inadvertently investigated high grade Du that are due to a suppressive effect of Cde and expected to possess a normal coding sequence. We excluded the possibility that we investigated some rare, previously uncharacterized partial D instead of weak D, because the phenotypes described by us occurred with a cumulative frequency of 0.41% and, therefore, accounted for the majority of weak D phenotypes. Weak D type 4 was partially characterized by Legler et al.14 These investigators performed sevenRHD-specific PCR reactions that were not affected by most mutations in weak D types. Their approach was not designed to exclude the kind of genetic diversity that is actually present in our weak D phenotypes.

Our findings implied that there is no well-defined borderline between weak D and partial D that has an aberrant RHD coding sequence, lacks specific D epitopes, and may be associated with an allo–anti-D. The observation of anti-D production in Rhesus positive recipients is too rare, even for some D categories, to base a classification on this event. Serologic discrimination of qualitative and quantitative abnormalities is prone to mistakes in samples with strongly reduced D antigen densities. A normal exofacial Rh sequence may be accompanied by alloimmunization, as exemplified by the VS antigen of the RhCE protein caused by the transmembraneous L245V substitution.47

Although multiple publication13,14,45,48-56 suggested a heterogeneity of weak D, a serologic classification of the majority of weak D phenotypes has not been successful. There was even no defined borderline between normal D and weak D.50,51,57,58 Our findings made the classification of weak D phenotypes feasible and their classification will allow us to correlate distinct alleles with clinical data. In the case that patients carrying certain molecular weak D types were prone to develop anti-D, our classification might guide a Rhesus negative transfusion policy. The availability of weak D samples that are characterized in regard to molecular structure and RhD antigen densities will promote the quality assurance of anti-D reagents. They should reliably type probands as RhD+, whose RhD proteins are not prone to frequent anti-D immunization.3 Therefore, the use of RhD−red blood cell units for transfusions to weak D patients, which has been justified by a presumed potential for anti-D immunization, can finally be reduced to a minimum, which can be scientifically deduced.

Some RHD alleles described in the present study were more prevalent than previously known RHD alleles. The potential for a broader relevance in research was opened, as it became feasible to determine in a massive way the frequencies of molecularly defined rare alleles in natural populations. Poisson-like allele distributions were predicted by mathematical models59 that could so far not be checked in any real population. We observed two alleles (type 4 and 14) with multiple nucleotide substitutions in the RHD gene that were characteristic for the RHCE gene, but may not be explained by a single gene conversion event. This observation pointed to more complicated mechanisms shaping the allele polymorphism of homologous genes, which are frequent throughout the genomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Olga Zarupski and Katharina Schmid for expert technical assistance.

Supported by the DRK-Blutspendedienst Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart, Germany.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Willy A. Flegel, Priv-Doz, MD, Abteilung Transfusionsmedizin, Universitätsklinikum Ulm, and DRK-Blutspendedienst Baden-Württemberg, Institut Ulm, Helmholtzstrasse 10, D-89081 Ulm, Germany; e-mail: waf@ucsd.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal