Abstract

PU.1 is an ets family transcription factor that is expressed specifically in hematopoietic lineages. Through gene disruption studies in mice we have previously shown that the expression of PU.1 is not essential for early myeloid lineage or neutrophil commitment, but is essential for monocyte/macrophage development. We have also shown that PU.1-null (deficient) neutrophils have neutrophil morphology and express neutrophil-specific markers such as Gr-1 and chloroacetate esterase both in vivo and in vitro. We now demonstrate that although PU.1-null mice develop neutrophils, these cells fail to terminally differentiate as shown by the absence of messages for neutrophil secondary granule components and the absence or deficiency of cellular responses to stimuli that normally invoke neutrophil function. Specifically, PU.1-deficient neutrophils fail to respond to selected chemokines, do not generate superoxide ions, and are ineffective at bacterial uptake and killing. The failure to produce superoxide could, in part, be explained by the absence of the gp91 subunit of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase, as shown by our inability to detect messages for the gp91phoxgene. Incomplete maturation of PU.1-deficient neutrophils is cell autonomous and persists in cultured PU.1-deficient cells. Our results indicate that PU.1 is not necessary for neutrophil lineage commitment but is essential for normal development, maturation, and function of neutrophils.

© 1998 by The American Society of Hematology.

NEUTROPHILS ARE key effector cells in the host defense response to microbial invasion. These cells are highly specialized for their function, which is to detect and neutralize primarily bacteria, but also fungi and parasites. Successful containment and elimination of microbial invasion requires an intact and coordinated cascade of events within neutrophils, from attraction and movement to the site of infection, to recognition and uptake of the organism, and effective killing mechanisms. The genes for a number of molecules involved in these processes have been cloned and have been shown by in vitro assays to be potentially regulated by the etsfamily transcription factor PU.1. Such genes include the β2 integrin components CD11b1 and CD18,2 neutrophil elastase,3 and Fcγ receptors I and III.4,5PU.1 is also implicated in the regulation of receptors for key myeloid growth factors including macrophage (M)-, granulocyte (G)-, and granulocyte-macrophage (GM)- colony-stimulating factor (CSF).6-8 These receptors influence the survival, proliferation, maturation, and functional capacity of neutrophils.9-11

Mice with a targeted disruption of the PU.1 gene exhibit multiple hematopoietic abnormalities. Although erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages are intact, PU.1-null mice are born with no detectable leukocytes. There is a delayed formation of the thymus, with T cells absent until approximately 1 week after birth.12Neutrophils, as defined by their segmented nuclear morphology content of chloroacetate esterase (CAE)13 and expression of Gr-114 are not apparent at birth in these mice, but do begin to appear in hematopoietic tissues several days afterward. The mice die within 2 days after birth of overwhelming systemic bacterial infection. They can be kept alive for up to 2 weeks with intensive antibiotic therapy during which time neutrophil numbers increase slightly but remain severely depressed compared with normal littermates.12 Mature macrophages and B cells are not detectable in PU.1-null mice of any age.

In our previous study15 we found that myeloid progenitors can give rise to cells with segmented nuclear morphology that are CAE- and Gr-1–positive. However, unlike normal neutrophils, interleukin-3 (IL-3), but not G-CSF, will support their survival and growth.15 Furthermore, PU.1-deficient neutrophils fail to express surface CD11b12 and PU.1-deficient myeloid cells either directly from mice or after short-term culture and have virtually undetectable levels of receptors for the myeloid growth factors G-, GM-, and M-CSF.15 In our current study we document that neutrophils deficient in PU.1 fail to perform important effector functions such as response to chemotactic stimuli or generation of a respiratory burst. We show that the absence of a respiratory burst (as demonstrated by superoxide production) is consistent with a failure of PU.1-deficient neutrophils to transcribe detectable messages for the gp91phox gene, which encodes a critical subunit of the enzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase. Additionally, these cells are less efficient at phagocytosis and less effective at bacterial killing than normal cells. Although PU.1-deficient cells do express primary (azurophil) granule component genes, they do not express detectable levels messages for secondary (specific) granule components, the appearance of which is associated with normal terminal neutrophil maturation beyond the promyelocyte stage.16 17 Finally, we have documented that cultured neutrophils derived from PU.1-null mice do not express PU.1 protein at a detectable level. The results of these studies are consistent with the interpretation that the PU.1 gene product is required for normal neutrophil function and terminal differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and culture of neonatal hematopoietic cells.

Cultures were derived by mechanically disrupting one to three whole neonatal livers, lysing red blood cells with 0.15 mol/L ammonium chloride solution, and plating remaining cells in a T25 tissue culture flask (Costar, Cambridge, MA). Cultures were maintained in Iscoves’s media supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum, 1% IL-3–conditioned media (from X63 cells, a gift of F. Melchers, Basel Institute), 1 ng/mL G-CSF, and 1 ng/mL GM-CSF (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Separation of neutrophils.

The combination of factors used (IL-3, G-CSF, and GM-CSF; as described above) yielded predominantly neutrophils from normal individuals between 5 and 10 days of culture. To separate neutrophils from normal cultures, nonadherent cells were removed from flasks and placed into a fresh tissue culture dish. Any remaining macrophages were permitted to adhere for 1 to 2 hours. After this step, the remaining nonadherent cells were >95% neutrophils as determined by Wright-Giemsa morphology. This was further confirmed by Gr-1 immunostaining of methanol-fixed cytospin preparations as described.12 A small number of macrophages and megakaryocytes (<5%) comprised the remainder of cells present.

Cytochemical staining.

Method for CAE staining was previously described.12

Measurement of neutrophil chemotaxis.

Chemotaxis was assessed using a 3-μm pore diameter polycarbonate membrane transwell apparatus (Costar) as directed by the manufacturer. Chemotactic agents added to the lower chamber included fMLP, 50 nmol/L (Sigma, St Louis, MO); and Groα and IL-8, 50 nmol/L (R & D Systems). To the upper chamber, 106 cells/mL in media were added and allowed to migrate in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C for 90 minutes (and for up to 4 hours). Negative control contained only media in the upper and lower compartments. Cell migration was assessed by counting the number of cells present in the bottom chamber after the incubation period.

Microassay of superoxide ion (O2−) production by cytochrome c reduction.

In a 96-well plate (Microtest III, Falcon; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) 105 neutrophils per well were suspended in a 100-mL volume of PiCM-G buffer18 containing 150 mmol/L cytochrome c (horse heart; Sigma). The method is a slight modification of previously published methods.18,19 Baseline O2− production was assessed by examining wells containing cells with no stimulant; blank wells contained cells plus the inhibitor superoxide dismutase (bovine erythrocyte; Sigma). Test wells contained cells plus 0.1 mg/mL phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma). Plates were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C and read at 550 nm. Absorbance was converted to nanomoles of O2− using the following extinction coefficient of cytochrome c: ΔE550 nm = 21 × 103 mol/L−1cm−1and the formula (nmol O2− per well) = (absorbance at 550 nm × 15.87) for the volume and plate type used.19

Neutrophil phagocytosis assay.

Heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus (American Type Culture Collection S aureus 502A) were labeled with 0.01% fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) isomer I (Sigma) for 30 minutes at room temperature and then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). In a 1-mL volume of Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) 107 labeled organisms were incubated with 106 normal or PU.1-deficient neutrophils for 2 hours at 37°C. To distinguish between bacteria adhered to the cell surface and internalized bacteria, which are a measure of phagocytosis, cells were then incubated with red cell lysing solution for 5 minutes, which quenches the signal from externally bound organisms.20 Cells were then stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled Gr-1 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Bacterial phagocytosis by Gr-1+ cells was assessed quantitatively with a Becton Dickinson FACScan and the two-color flow cytometry results were analyzed using Cell Quest (Becton Dickinson). General conditions for flow cytometry analysis were as previously described.12

Neutrophil killing of live bacterial organisms.

Bacterial uptake and killing by neutrophils was assessed as previously described.21 In HBSS with 107 live S aureus(502A) or Escherichia coli (JM109), 2 × 106 cells from normal or PU.1-null neonatal liver cultures were suspended for 2 hours in a volume of 1 mL. Before incubation for 2 hours, 0.1 mL of a 1:10,000 dilution of the cells and bacteria (equivalent to 100 bacteria) was immediately removed and plated to serve as a Time 0 (control) colony count. Selection of bacterial growth media was as previously described.21 Time 0 plates were counted after 24 hours at 37°C. To determine total viable bacteria, 0.1 mL of the cells and bacteria mixture was diluted in water to lyse cells, then diluted similarly to Time 0 samples and plated in appropriate medium. Colonies were counted after a 24-hour incubation at 37°C. The percent of total viable bacteria was calculated as: (24-hour colony count of total intracellular and extracellular bacteria remaining after 2-hour incubation with cells/colony count for Time 0) × 100. To determine viable intracellular bacteria, 0.1 mL of the mixture was incubated with 500 U/mL lysostaphin for 20 minutes at 37°C to kill remaining extracellular bacteria (Saureus) or differentially centrifuged to pellet cells but not free bacteria (E coli), diluted, and then cells were lysed in water and plated. Colonies were counted after a 24-hour incubation at 37°C. The percent of viable intracellular bacteria was calculated as: (24-hour colony count of intracellular bacteria remaining after 2-hour incubation with cells after removal of extracellular bacteria/colony count for Time 0) × 100. Samples were run in triplicate and results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Isolation of RNA and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from 0.5 to 5 × 106 cultured cells using Trizol (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) as directed by the manufacturer and subjected to DNase I treatment (10 U for 30 minutes at 37°C; Boehringer-Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Total RNA (0.25 μg) was reverse transcribed using Superscript II (GIBCO-BRL) and one tenth of the reaction subjected to PCR using the following conditions: 94°C × 1 minute, 55°C to 65°C × 1 minute, 72°C × 1 minute for 30 cycles in a Perkin-Elmer thermocycler (GeneAmp 9600; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT). Negative control reactions for RT-PCR contained RNA template that had not undergone reverse transcription. An aliquot (25 μL) of each 50-μL PCR reaction was run in a 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide and photographed. PCR primers used included the following (listed 5′ to 3′): myeloperoxidase: 5′ ATGCAGTGGGGACAGTTTCTG; 3′ GTCGTTGTAGGATCGGTACTG; elastase: 5′ CACCATCAGTCAGGTCTTCC; 3′ AGTCTCCGAAGCATATGCC; cathepsin G: 5′ CTGACTAAGCAACGGTTCTGG; 3′ GATTGTAATCAGGATGGCGG; lysozyme: 5′ CTGCAGGATGACATCACTGC; 3′ TGCTGAGGCCTGTACTTAGAGG; lactoferrin: 5′ AAGCCAGGCTTGTCCTCTAG; 3′ TCTCATCTCGTTCTGCCACC; gelatinase: 5′ ACGGTTGGTACTGGAAGTTCC; 3′ CCAACTTATCCAGACTCCTGG; gp91: 5′ TTGTGAGAGGTTGGTTCGG; 3′ TCCAGTCTCCAACAATACGG; p22: 5′ AGGGGTCCACCATGGAGCGA; 3′ GCTCAATGGGAGTCCACTGC; p47: 5′ AACGTAGCTGACATCACAGGC; 3′ TCCAGGAGCTTATGAATGACC; p67: 5′ GCTATTTGGGTTTGTGCCTG; 3′ GGAACAAGCCCCTTCTGCCC.

Western blot detection of PU.1.

Cells were cultured and obtained as described above. Total cell extracts were prepared by lysis in RIPA buffer (PBS, 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) plus protease inhibitors. Nuclear extracts were prepared from 106 to 107 cells as described.22 Proteins were resolved in a 10% to 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; Amersham LifeScience, Arlington Heights, IL). Full-length PU.1-GST fusion protein and anti-PU.1-GST antibody were made as follows. PU.1 cDNA was amplified by PCR from the plasmid 25.1-123 with primers containing BamHI orEcoRI ends and gel purified. PGEXKG (a derivative of PGEX2T) was digested with BamHI and EcoRI. The amplified PU.1 fragment was subcloned into the vector and the insert was sequenced. Bacteria were transformed and PU.1-GST fusion protein purified from bacteria using glutathione agarose beads as described.24Rabbits were immunized repeatedly with the purified PU.1-GST fusion protein and antiserum collected. This antiserum was affinity purified before use in Western blotting. Alternately, commercially available anti-PU.1 polyclonal antibody directed against the C-terminus of PU.1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used. Polyclonal antiactin antibody was obtained from Sigma. Secondary antibody was peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz). These antibodies were incubated with the blotted membrane, and immunoreactive proteins detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham) visualization method.

RESULTS

PU.1-deficient neutrophils have an aberrant phenotype in vivo and in vitro.

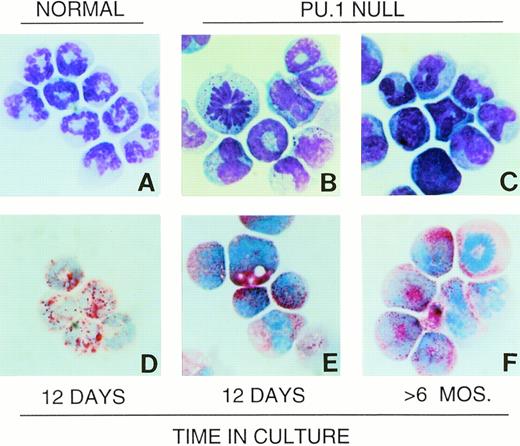

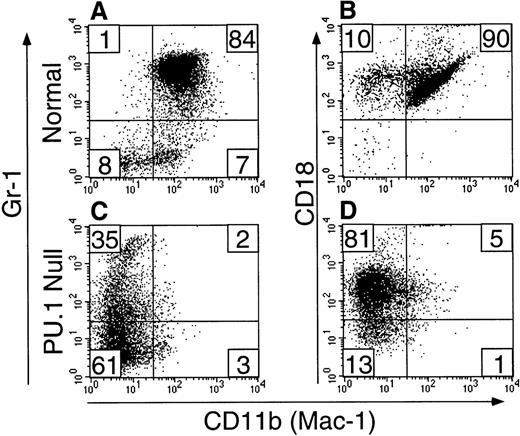

Neutrophils typically have multilobed nuclei and light blue to colorless cytoplasm containing variable sizes and number of azurophilic granules25 (Fig 1A). Cells identified as neutrophils in PU.1-null mice shared this basic morphology. These cells stained positively for the neutrophil surface marker Gr-112 and for the intracellular enzyme chloroacetate (specific) esterase (CAE). Gr-1+ cells from PU.1-null mice were also CD18+.12 However, unlike normal neutrophils, the majority did not have detectable cell surface CD11b.12 We previously showed that PU.1-deficient hematopoietic cells did not survive or grow when cultured in the presence of either M-CSF, G-CSF, or GM-CSF, and this is due at least in part to a failure to express surface receptors for these cytokines.15 In contrast, IL-3 did support PU.1-deficient hematopoietic cell survival and expansion. When PU.1-null neonatal liver, spleen, or bone marrow cells were cultured in IL-3, the majority of cells produced had neutrophil morphology as shown in Fig 1B and C, and histochemical and flow cytometric analysis showed these cells to be CAE+ (Fig 1E and F), Gr-1+(Fig 2C), CD18+ (Fig 2D), and primarily CD11b− (Fig 2D). Unlike cultures established from normal neonatal liver in which large numbers of terminally differentiated neutrophils were produced in the first 2 weeks but then neutrophil production dropped off dramatically, cultures established from PU.1-null neonates producing neutrophils as the principal cell type have been maintained for longer than 6 months (Fig1C and F). The CAE, Gr-1, CD18, and CD11b staining characteristics of these long-term cultured PU.1-deficient cells were identical to short-term (<2 weeks) cultured PU.1-deficient cells, as well as cells isolated directly from older PU.1-null mice (Fig 1 and Fig 2, data not shown).

Wright-Giemsa morphology and CAE staining characteristics of PU.1-deficient neutrophils are similar to neutrophils from normal individuals. Neutrophils cultured from normal neonates as described in Materials and Methods are shown (A). Cells cultured from neonatal PU.1-null mice after 12 days (B) and >6 months (C) have similar polymorphonuclear morphology. Note presence of mitotic cells in PU.1-deficient cultures (B and F). Abundant CAE activity as indicated by red granules in PU.1-deficient cells (E and F) is also evident, as in normal neutrophils (D).

Wright-Giemsa morphology and CAE staining characteristics of PU.1-deficient neutrophils are similar to neutrophils from normal individuals. Neutrophils cultured from normal neonates as described in Materials and Methods are shown (A). Cells cultured from neonatal PU.1-null mice after 12 days (B) and >6 months (C) have similar polymorphonuclear morphology. Note presence of mitotic cells in PU.1-deficient cultures (B and F). Abundant CAE activity as indicated by red granules in PU.1-deficient cells (E and F) is also evident, as in normal neutrophils (D).

Gr-1+ PU.1-deficient neutrophils are deficient in CD11b, but not CD18 expression. Short-term cultured (see Materials and Methods) liver-derived hematopoietic cells from normal (panels A and B) or PU.1-null (panels C and D) neonatal mice were assessed by two-color flow cytometry for CD11b (FITC) and Gr-1 (PE) (panels A and C) or CD11b (FITC) and CD18 (PE) (panels B and D) expression. Note the vastly reduced expression of CD11b on PU.1-deficient cells (compare panels A and C) but the presence of CD18 on the majority (86%) of the PU.1-deficient cells (compare panels B and D).

Gr-1+ PU.1-deficient neutrophils are deficient in CD11b, but not CD18 expression. Short-term cultured (see Materials and Methods) liver-derived hematopoietic cells from normal (panels A and B) or PU.1-null (panels C and D) neonatal mice were assessed by two-color flow cytometry for CD11b (FITC) and Gr-1 (PE) (panels A and C) or CD11b (FITC) and CD18 (PE) (panels B and D) expression. Note the vastly reduced expression of CD11b on PU.1-deficient cells (compare panels A and C) but the presence of CD18 on the majority (86%) of the PU.1-deficient cells (compare panels B and D).

Neutrophils lacking PU.1 fail to respond to chemotactic stimuli.

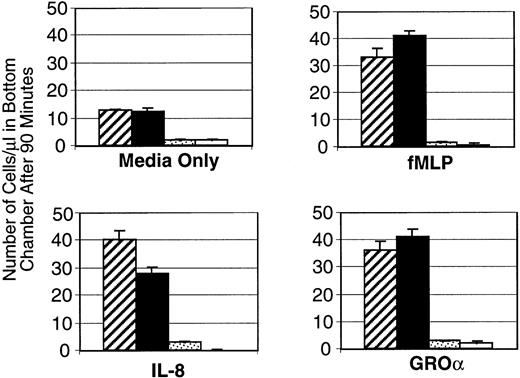

To effectively control infection, neutrophils must detect and respond to bacterial invasion. Many different molecules associated with the inflammatory process can attract peripheral blood neutrophils to the affected tissue site. These chemotactic factors include products released from the invading organisms themselves (such as N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine [fMLP] or lipopolysaccharide) as well as those produced by the host, including plasma-derived components like complement fragment 5a, and cell-secreted molecules such as IL-8.26 To test the responsiveness of PU.1-deficient versus normal cells in vitro three different chemokines were used. Neutrophils that were isolated and expanded as described (see Materials and Methods) were assessed for their ability to respond to IL-8, Groα, and fMLP by using standard migration assays. PU.1-deficient cells did not respond to any of these chemotactic agents at any significant level above background (media only) (Fig 3). In comparison, normal cells migrated at a higher level in the wells with media alone, and increased their migration threefold to fourfold on exposure to chemokines (Fig3). When the migration period was extended to as long as 4 hours, PU.1-deficient cells still did not migrate above background levels (data not shown). We detected expression of messages for IL-8 and fMLP receptors in both normal and PU.1-deficient neutrophils using RT-PCR (data not shown). This suggests that absence of receptor gene expression did not account for the loss of chemotactic response of PU.1-deficient cells. However, the presence of IL-8 and fMLP surface receptors was not directly assessed. Interestingly, when exposed to fMLP or PMA, PU.1-deficient cells could be induced to adhere to untreated plastic dishes at a level comparable to normal cells (data not shown). Thus this aspect of chemotaxis was not demonstrably affected.

PU.1-deficient neutrophils fail to respond to chemokines. Normal (▨,▪) or PU.1-deficient (▧,□) cells migrating across a transwell device were counted after 90 minutes in the presence of IL-8, fMLP, GRO, or media alone. Samples were run in triplicate and the results of a representative experiment are presented as mean ± SD.

PU.1-deficient neutrophils fail to respond to chemokines. Normal (▨,▪) or PU.1-deficient (▧,□) cells migrating across a transwell device were counted after 90 minutes in the presence of IL-8, fMLP, GRO, or media alone. Samples were run in triplicate and the results of a representative experiment are presented as mean ± SD.

PU.1-deficient cells fail to undergo normal neutrophil activation.

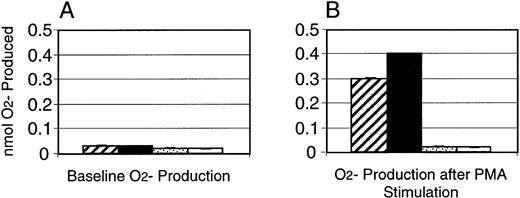

On exposure to various molecules associated with inflammation, including bacterial components and other soluble factors such as IgG immune complexes in vivo or PMA in vitro, the normally glycolytic neutrophil rapidly undergoes a dramatic increase in oxygen consumption. This is referred to as the neutrophil “respiratory burst,”27 during which reactive oxygen metabolites are generated. To test the ability of PU.1-deficient neutrophils to produce the crucial metabolite superoxide (O2−), deficient and normal neutrophils were stimulated with PMA and scored for their ability to reduce the dye nitroblue tetrazolium. Microscopic assessment of cells revealed that 50% of neutrophils from normal mice were positive for the reaction product after stimulation, whereas no detectable black precipitate was seen in the PU.1-deficient cells (data not shown). To specifically quantitate production of O2−, a superoxide dismutase-inhibitable cytochrome c reduction assay was performed. Baseline and PMA-stimulated O2− production by PU.1-deficient neutrophils was minimal and identical, and less than baseline production by normal neutrophils as well (Fig 4). In comparison, normal cells increased O2− production roughly 10-fold after stimulation with PMA (Fig 4).

Absence of production of O2− by PU.1-deficient neutrophils in response to activation by PMA. O2− production was assessed in normal (▨,▪) and PU.1-deficient (▧,□) neutrophils by colorimetric detection of cytochrome c reduction. Baseline (A) and post-PMA stimulation (B) levels of O2− were measured. Samples were run in triplicate and the results of a representative experiment are presented as mean ± SD.

Absence of production of O2− by PU.1-deficient neutrophils in response to activation by PMA. O2− production was assessed in normal (▨,▪) and PU.1-deficient (▧,□) neutrophils by colorimetric detection of cytochrome c reduction. Baseline (A) and post-PMA stimulation (B) levels of O2− were measured. Samples were run in triplicate and the results of a representative experiment are presented as mean ± SD.

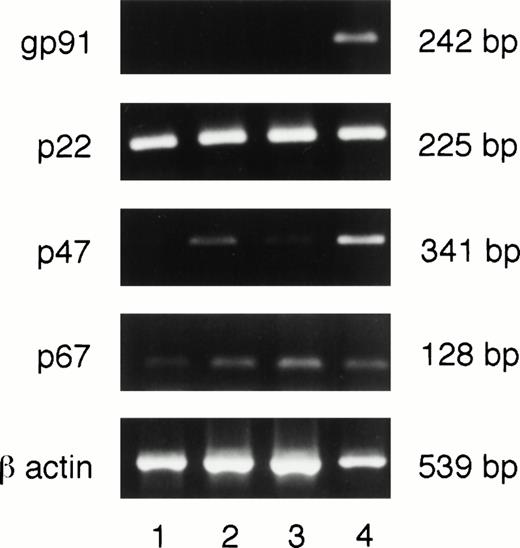

Message for gp91phox is undetectable in PU.1-deficient neutrophils.

A single enzyme, NADPH oxidase, is responsible for O2− production in myeloid cells. This enzyme is composed of two membrane bound subunits, gp91 and p22, and two cytoplasmic subunits, p47 and p67, which are synthesized constitutively in myeloid cells. When the cells receive an appropriate stimulus, the subunits are assembled on the membrane to form an active complex. To determine whether any or all of the subunits were absent, cultured PU.1-deficient neutrophils were assessed for message for the various subunits by RT-PCR. We selected message- rather than protein-based detection of NADPH oxidase components, given the instability of p22 or gp91 proteins in the absence of its respective partner and the possibility of low amounts of protein components in cultured PU.1-deficient neutrophils. As can be seen in Fig 5, messages for all subunits were detectable with the exception of gp91phox. Our results from RT-PCR do not allow us to determine if the loss of PU.1 alters p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox message levels. Thus, failure to generate O2− by PU.1-deficient cells (Fig 4) seems, at least in part, to be due to the absence of detectable message for the gp91 subunit of NADPH oxidase.

Neutrophils deficient in PU.1 fail to transcribe the gp91phoxgene. RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed, and subjected to PCR as described in Materials and Methods. These samples were obtained from 2-week cultures. All NADPH oxidase component subunits were detectable in one normal (lane 4) and three different PU.1-deficient cultured neutrophil samples (lanes 1 through 3) by this method except for gp91, which was only found in normal cells. Controls for amplification of DNA in the absence of reverse transcription for each reaction were negative; these data are not shown. bp, base pairs.

Neutrophils deficient in PU.1 fail to transcribe the gp91phoxgene. RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed, and subjected to PCR as described in Materials and Methods. These samples were obtained from 2-week cultures. All NADPH oxidase component subunits were detectable in one normal (lane 4) and three different PU.1-deficient cultured neutrophil samples (lanes 1 through 3) by this method except for gp91, which was only found in normal cells. Controls for amplification of DNA in the absence of reverse transcription for each reaction were negative; these data are not shown. bp, base pairs.

PU.1-deficient neutrophils are less efficient phagocytes.

We used flow cytometry to assess the ability of Gr-1+neutrophils to ingest FITC-labeled, heat-killed Saureus (SAFITC) in vitro. After incubation with labeled bacteria, neutrophils were treated with an agent to differentiate between surface-bound and internalized bacteria.20 As shown in Table1, Gr-1+ PU.1-deficient neutrophils were capable of bacterial uptake (12% and 6% v 16% SAFITC+/Gr-1PE+ cells), with only slight differences in the numbers of Gr-1+ PU.1-deficient neutrophils capable of bacterial uptake as compared with controls. More striking was the difference in quantity of SAFITC ingested, as reflected by higher median FITC channel fluorescence of normal neutrophils (217) as compared with PU.1-deficient samples (83 and 160). Addition of IgG or serum as an opsonin to the reaction mix did not increase the level of phagocytosis (data not shown). We subsequently determined whether receptors for IgG (FcγR) were present on Gr-1+ cells. Similar percentages of Gr-1+/FcγR+ cells were seen in normal and PU.1-deficient cultured cells (data not shown), although the antibody used did not allow distinction between FcγR types II and III. Therefore, the reduced uptake of bacteria by PU.1-deficient cells does not seem to be the consequence of failure to express any surface receptors for IgG, although each type was not specifically assessed and quantified. Furthermore, uptake of unopsonized bacteria by PU.1-deficient cells was also reduced compared with normal cells and this is not dependent on Fc receptors. These results indicate that Gr-1+ PU.1-deficient neutrophils are somewhat less efficient phagocytes than their normal counterparts.

Gr-1+ PU.1-Null Cells Phagocytose Heat-Killed FITC-Labeled S aureus

| Cell Source* . | Percent of Gr-1+ Cells After Culture-151 . | Percent of Gr-1+ Cells Binding SAFITC -152 . | Percent of Gr-1+ Cells Binding SAFITC After Quenching-153 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| PU.1 normal | 88 | 18 (221) | 16 (217) |

| PU.1 null (#503) | 59 | 20 (87) | 12 (83) |

| PU.1 null (#665) | 62 | 24 (191) | 6 (160) |

| Cell Source* . | Percent of Gr-1+ Cells After Culture-151 . | Percent of Gr-1+ Cells Binding SAFITC -152 . | Percent of Gr-1+ Cells Binding SAFITC After Quenching-153 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| PU.1 normal | 88 | 18 (221) | 16 (217) |

| PU.1 null (#503) | 59 | 20 (87) | 12 (83) |

| PU.1 null (#665) | 62 | 24 (191) | 6 (160) |

*Cells from PU.1-normal or -null neonatal liver were cultured for 2 weeks before use (see Materials and Methods). In a 1-mL volume of Hanks’ balanced Salt Solution, 107 FITC-labeled S aureus (SA) were incubated with 106 normal or PU.1-null neutrophils for 2 hours at 37°C. Samples were washed and then incubated with rat anti–Gr-1PE antibody to identify neutrophils. Samples were then analyzed by two-color flow cytometry for the presence of neutrophils that contained bacteria.

Gr-1 was used to estimate the number of neutrophils in samples from PU.1-normal or -null neonatal liver cultures.

This number reflects the percentage of neutrophils containing detectable SAFITC, whereas the value in parentheses reflects the median channel fluorescence of SAFITC present.

This number represents the percentage of neutrophils containing detectable SAFITC after chemical quenching of cell-bound bacteria (see Materials and Methods), thereby reflecting internalized bacteria protected from chemical quenching, and thus providing a measure of phagocytosis by neutrophils.

Neutrophils deficient in PU.1 are less effective at uptake and killing of live bacteria.

The uptake of bacteria by neutrophils is normally followed by killing of the organisms within the phagocytic vacuole. The microbicidal capabilities of neutrophils are broadly grouped into oxygen-dependent and oxygen-independent mechanisms. The former group includes NADPH oxidase and myeloperoxidase, and its effectiveness centers on the ability to generate reactive oxygen radicals. The latter group includes an array of antimicrobial cationic proteins and hydrolytic enzymes, such as cathepsin G, lactoferrin, and lysozyme. PU.1-deficient neutrophils lack the ability to generate O2−; therefore we tested the ability of PU.1-deficient and normal cells to kill live S aureus and E coli organisms in vitro. As summarized in Table 2, PU.1-deficient cells are notably less effective in the uptake (with 1.7 to 4.6 times greater total viable bacteria remaining in PU.1-deficient samples) and killing (with 2 to 20 times greater viable intracellular bacteria recovered from PU.1-deficient samples) of both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria.

Bacterial Uptake and Killing by Normal and PU.1-Null Neutrophils

| . | % Total Viable Bacteria* . | % Viable Intracellular Bacteria† . |

|---|---|---|

| S aureus | ||

| Experiment 1 | ||

| Normal (pooled) | 12.7 ± 2.5 | 2.3 ± 0.6 |

| PU.1 Null #1 | 58.5 ± 1.3 | 34.0 ± 6.6 |

| PU.1 Null #2 | 54.6 ± 1.2 | 46.3 ± 8.1 |

| Experiment 2 | ||

| Normal (pooled) | 27.0 ± 4.6 | 4.0 ± 3.0 |

| PU.1 Null (pooled) | 46.2 ± 0.4 | 48.0 ± 7.1 |

| E. coli | ||

| Experiment 1 | ||

| Normal (pooled) | 15.8 ± 1.9 | 16.2 ± 5.8 |

| PU.1 Null (pooled) | 66.6 ± 7.5 | 33.1 ± 6.1 |

| Experiment 2 | ||

| Normal (pooled) | 18.3 ± 1.4 | 17.3 ± 2.5 |

| PU.1 Null (pooled) | 71.0 ± 1.8 | 54.3 ± 5.3 |

| . | % Total Viable Bacteria* . | % Viable Intracellular Bacteria† . |

|---|---|---|

| S aureus | ||

| Experiment 1 | ||

| Normal (pooled) | 12.7 ± 2.5 | 2.3 ± 0.6 |

| PU.1 Null #1 | 58.5 ± 1.3 | 34.0 ± 6.6 |

| PU.1 Null #2 | 54.6 ± 1.2 | 46.3 ± 8.1 |

| Experiment 2 | ||

| Normal (pooled) | 27.0 ± 4.6 | 4.0 ± 3.0 |

| PU.1 Null (pooled) | 46.2 ± 0.4 | 48.0 ± 7.1 |

| E. coli | ||

| Experiment 1 | ||

| Normal (pooled) | 15.8 ± 1.9 | 16.2 ± 5.8 |

| PU.1 Null (pooled) | 66.6 ± 7.5 | 33.1 ± 6.1 |

| Experiment 2 | ||

| Normal (pooled) | 18.3 ± 1.4 | 17.3 ± 2.5 |

| PU.1 Null (pooled) | 71.0 ± 1.8 | 54.3 ± 5.3 |

*2 ×106 neutrophils were incubated with 107 live S aureus 502A or E coli JM109 (please see Materials and Methods for complete protocols). The percent total viable bacteria were calculated as: (24-hr colony count of intracellular and extracellular bacteria remaining after 2-hr incubation with cells/colony count for Time 0) × 100. Samples were run in triplicate and results are reported as mean ± SD.

After extracellular bacteria were removed by lysis or centrifugation, the percent viable intracellular bacteria remaining was calculated as: (24-hr colony count of intracellular bacteria remaining after 2-hr incubation with cells/colony count for Time 0) × 100. Samples were run in triplicate and results are reported as mean ± SD.

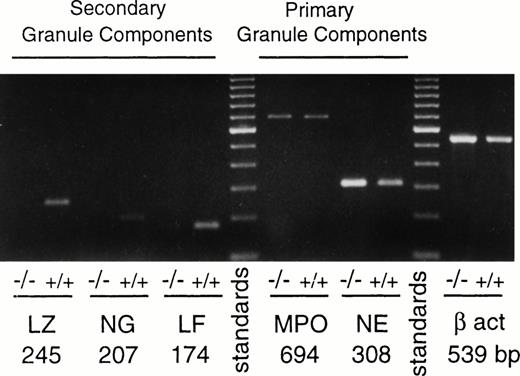

PU.1-deficient neutrophils express primary granule genes but fail to express specific granule genes.

The promyelocyte stage of neutrophil development is characterized by the appearance of azurophil (primary) granule components such as myeloperoxidase, neutrophil elastase, and cathepsin G. Messages for these components were readily detected in both PU.1-deficient and normal cultured neutrophils (Fig 6 and data not shown). Normal and PU.1-deficient neutrophils also had comparable levels of myeloperoxidase enzyme activity (data not shown). However, certain genes that are normally expressed at the later myelocyte stage, encoding the secondary (or specific) granule components neutrophil gelatinase and lactoferrin, were either not detected (gelatinase) or expressed episodically at a virtually undetectable level (lactoferrin) in PU.1-deficient cells as compared with normal cells (Fig 6). Interestingly, lysozyme, another component of neutrophil granules found in both primary and secondary granules,27 did not appear to be expressed in PU.1-deficient cells at a detectable level (Fig 6).

Primary but not secondary granule genes are expressed in PU.1-deficient neutrophils. RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed, and subjected to PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown are from representative normal (+/+) and PU.1-deficient (−/−) cells cultured for 2 weeks as described in Materials and Methods. Controls for amplification of DNA in the absence of reverse transcription for each reaction were negative; these data are not shown. β act, β actin; NE, neutrophil elastase; MPO, myeloperoxidase; LF, lactoferrin; NG, neutrophil gelatinase; LZ, lysozyme.

Primary but not secondary granule genes are expressed in PU.1-deficient neutrophils. RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed, and subjected to PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown are from representative normal (+/+) and PU.1-deficient (−/−) cells cultured for 2 weeks as described in Materials and Methods. Controls for amplification of DNA in the absence of reverse transcription for each reaction were negative; these data are not shown. β act, β actin; NE, neutrophil elastase; MPO, myeloperoxidase; LF, lactoferrin; NG, neutrophil gelatinase; LZ, lysozyme.

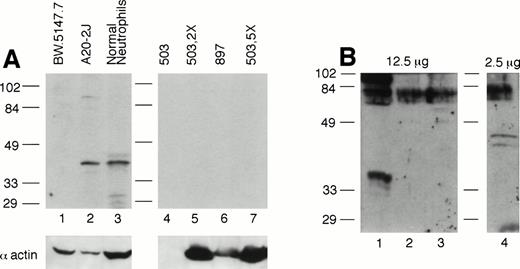

PU.1 protein is undetectable in cultured neutrophils from PU.1-null mice.

Given the possibility in gene-disrupted mice of read-through or splicing-out of the targeting cassette in the targeted gene, thus generating a partial or aberrant protein or reduced amount of full-length protein, we assessed PU.1 expression in PU.1-deficient cultured cells by Western blotting. Because PU.1 messages are normally highly expressed in neutrophils,28 these cells represent an ideal population to examine. We used antisera recognizing both the C-terminal portion of PU.1 as well as one raised against an entire PU.1-GST fusion protein. Figure 7A depicts PU.1 expression in normal and PU.1-deficient cultured neutrophil total cell extracts using the anti–C-terminal antibody. Whereas a PU.1 signal was detected in 50 μg of whole cell extract from normal neutrophils (lane 3) and the B-cell line A20-2J (lane 2), it was not detected in 50 (lanes 4 and 6), 100 (lane 5), or 250 μg (lane 7) of PU.1-deficient cell extract. Using a polyclonal anti–PU.1-GST antisera, we were able to detect a PU.1 signal using 2.5 μg of nuclear extract from normal neutrophils (Fig 7B, lane 4). In contrast, even when a fivefold excess of nuclear protein from PU.1-deficient cultured neutrophils was probed, no PU.1 signal was evident (Fig 7B, lanes 2 and 3). Thus, we conclude that PU.1 gene targeting has effectively resulted in undetectable levels of the PU.1 gene product in this lineage.

PU.1 protein is detectable in normal neutrophils but not PU.1-deficient neutrophils. (A) Total protein prepared from cultured neutrophils was separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, blotted, and probed with an antibody directed against the C-terminus of PU.1 (Santa Cruz). Note PU.1 signal around 40 kD in 50 μg of extract from the B-cell line A20-2J (lane 2) and normal neutrophils (lane 3), but not in lanes 4 through 7 containing 50 μg (lanes 4 and 6), 100 μg (lane 5), and 250 μg (lane 7) from PU.1-deficient neutrophil cell lines (#503 and #897) derived from two different PU.1-null mice. Although lane 4 containing #503 did not react with the antiactin antibody, lanes 5 and 7 (containing a twofold and fivefold excess of the same extract) clearly reflect an excess of protein present and show no PU.1 signal. Lane 1 contains the T-cell line BW.5147.7 that does not express PU.1. (B) Nuclear protein, 2.5 to 12.5 μg, prepared from cultured cells was separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, blotted, and probed with a polyclonal anti–PU.1-GST fusion protein antibody. No signal was detectable in PU.1-deficient cell lines in lanes 2 and 3 even at a fivefold excess of nuclear protein compared with normal neutrophils in lane 4. Lane 1 contains the T-cell line EL-4 which does not express PU.1.

PU.1 protein is detectable in normal neutrophils but not PU.1-deficient neutrophils. (A) Total protein prepared from cultured neutrophils was separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, blotted, and probed with an antibody directed against the C-terminus of PU.1 (Santa Cruz). Note PU.1 signal around 40 kD in 50 μg of extract from the B-cell line A20-2J (lane 2) and normal neutrophils (lane 3), but not in lanes 4 through 7 containing 50 μg (lanes 4 and 6), 100 μg (lane 5), and 250 μg (lane 7) from PU.1-deficient neutrophil cell lines (#503 and #897) derived from two different PU.1-null mice. Although lane 4 containing #503 did not react with the antiactin antibody, lanes 5 and 7 (containing a twofold and fivefold excess of the same extract) clearly reflect an excess of protein present and show no PU.1 signal. Lane 1 contains the T-cell line BW.5147.7 that does not express PU.1. (B) Nuclear protein, 2.5 to 12.5 μg, prepared from cultured cells was separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, blotted, and probed with a polyclonal anti–PU.1-GST fusion protein antibody. No signal was detectable in PU.1-deficient cell lines in lanes 2 and 3 even at a fivefold excess of nuclear protein compared with normal neutrophils in lane 4. Lane 1 contains the T-cell line EL-4 which does not express PU.1.

DISCUSSION

The neutrophil lineage is affected in multiple ways by loss of PU.1 expression. Cells displaying neutrophil markers do not appear in PU.1-null mice until 2 to 3 days after birth, compared with appearance in normal mice around embryonic day 12. Additionally, neutrophil numbers remain extremely low (10- to 100-fold reduced depending on the tissue) in PU.1-null mice by 10 days after birth (K.L.A. and B.E.T., unpublished data, February 1996). The cells that develop in the PU.1-null mouse have segmented nuclear morphology, express Gr-1,14 and the neutrophil enzyme CAE.13However, unlike normal neutrophils, very few Gr-1+PU.1-deficient cells express CD11b, although most Gr-1+ cells from these mice express CD1812 (Fig 2). As we have recently documented, PU.1-deficient hematopoietic cells have virtually undetectable surface receptors for the myeloid growth factors M-, G-, and GM-CSF.15 These characteristics persist when PU.1-deficient cells are expanded in in vitro cultures using IL-3.15

The stages of neutrophil differentiation are identified by the acquisition of characteristic morphological features and the expression of various surface receptors and intracellular proteins. As necessary molecular components are synthesized, the developing neutrophils attain functional competency. The capacity for cell division is normally lost as the cells achieve later stages of differentiation. One of the earliest recognizable stages, the promyelocyte, is associated with active primary granule component synthesis. At the subsequent myelocyte stage, secondary or specific granule components are produced. Myelocytes also begin to acquire the capacity for the functions of mobility and phagocytosis. Furthermore, mitosis is still possible at this stage but not at subsequent stages. The more mature, nonmitotic stages (metamyelocytes, bands, and mature neutrophils) are identified by their increasingly segmented nuclear morphology, decreasing granule content, and increasing glycogen accumulation.27

Gr-1+ CAE+ neutrophils that develop with no detectable PU.1 protein can be expanded in vitro. These cells have characteristics of immature neutrophil stages but lack certain features and abilities associated with mature neutrophils. In comparison to neutrophils cultured from normal animals which achieve terminal differentiation and die, cells derived from PU.1-null mice continue to proliferate indefinitely. PU.1-deficient cells are unresponsive to G- and GM-CSF, and will only survive and grow in IL-3–containing medium.15 Their phenotypic and functional characteristics are summarized in Table 3. We have detected expression of primary granule genes, including myeloperoxidase, elastase, and cathepsin G. Expression of elastase is notable because this promoter has been shown to be regulated by PU.1 in vitro; however, these investigators also found transactivation of their promoter construct by ets-2,3 a ubiquitously expressed etsprotein.29 Thus, in vivo complementation to some degree by other ets family members may account for our observation of elastase messages in PU.1-deficient neutrophils. Although Spi-B is more closely related to PU.1 than other ets family members, and shares the ability to bind to a number of the same promoter elements in vitro, this transcription factor is not detectably expressed in normal28 or PU.1-deficient neutrophils (K.L.A., unpublished results). Finally, the absence of detectable messages for lysozyme, a granule protein found in both primary and secondary granules, is notable. Given the presence of messages for other primary granule genes in PU.1-deficient neutrophils, and the demonstration that PU.1 can activate the myeloid-specific enhancer of the chicken lysozyme gene,30 it is tempting to speculate that transcription of the lysozyme gene, in contrast to the elastase gene, requires PU.1.

Neutrophil Phenotype in PU.1-Null Mice Compared With Normal Mice

| Normal | PU.1 Null | Normal | PU.1 Null | ||

| Gr-1P | + | + | FcγRII/IIIP | + | + |

| CAEP | + | + | MPOP/R | + | + |

| CD18P | + | + | CathepsinGR | + | + |

| CD11bP | + | − | ElastaseR | + | + |

| G-CSFRP | + | − | LysozymeR | + | − |

| GM-CSFRP | + | − | LactoferrinR | + | ± |

| IL-8RR | + | + | GelatinaseR | + | − |

| fMLPRR | + | + |

| Normal | PU.1 Null | Normal | PU.1 Null | ||

| Gr-1P | + | + | FcγRII/IIIP | + | + |

| CAEP | + | + | MPOP/R | + | + |

| CD18P | + | + | CathepsinGR | + | + |

| CD11bP | + | − | ElastaseR | + | + |

| G-CSFRP | + | − | LysozymeR | + | − |

| GM-CSFRP | + | − | LactoferrinR | + | ± |

| IL-8RR | + | + | GelatinaseR | + | − |

| fMLPRR | + | + |

| Normal | PU.1 Null | |

| Neutrophil Functions | ||

| Adherence (+PMA) | Present | Present |

| Chemotaxis | ||

| fMLP | Present | Absent |

| IL-8 | Present | Absent |

| Groα | Present | Absent |

| Activation | ||

| O2− production | Present | Absent |

| Phagocytosis | Present | Reduced |

| Bacterial killing | Present | Reduced |

| Normal | PU.1 Null | |

| Neutrophil Functions | ||

| Adherence (+PMA) | Present | Present |

| Chemotaxis | ||

| fMLP | Present | Absent |

| IL-8 | Present | Absent |

| Groα | Present | Absent |

| Activation | ||

| O2− production | Present | Absent |

| Phagocytosis | Present | Reduced |

| Bacterial killing | Present | Reduced |

Unlike messages for primary granule component genes, however, those encoding secondary or specific granule components are not detectably expressed in PU.1-deficient cells. Because the onset of transcription of these genes occurs at a stage-specific point of neutrophil maturation, it has been hypothesized that all of these genes are regulated by a common trans-acting factor.31 Furthermore, individuals with the rare congenital disorder specific granule deficiency that have absent or abnormal specific granules and severely deficient or absent granule proteins have no or minimal mRNA for any of the specific granule components, lending further credence to this theory.32,33 The episodic and virtually undetectable message for lactoferrin might be consistent with the possibility that PU.1-deficient neutrophils are attempting to initiate programs for later stages of development, but cannot do so because of a developmental arrest. Myeloid leukemia cells such as HL60 do not express these proteins even when induced to differentiate along the granulocyte pathway.34 Thus, the appearance of these components is associated with late stages of normal neutrophil maturation. To date, PU.1 regulatory elements have not been shown in the promoter regions of specific granule genes, and it is not known whether PU.1 plays a direct or indirect role in the normal regulation of these genes. Conceivably, signaling through CD11b or G- or GM-CSF receptors, which are not expressed on PU.1-deficient neutrophils, may be required for activation of specific granule genes in developing neutrophils via other transcription factors. Mice that have been gene disrupted for these individual receptors or their corresponding cytokines35-39 have not been specifically assessed for expression of these genes; however, descriptions of their respective phenotypes do not support a specific granule deficiency. Alternatively, PU.1 may be responsible for regulating the transcription or activity of factor(s) that directly regulate these promoters. Complementation experiments with PU.1 as well as CD11b and G- and GM-CSF receptors are underway to address these questions.

The acquisition of full functional competency is also associated with the final stages of neutrophil maturation. The functional deficiencies of neutrophils lacking PU.1 are summarized in Table 3. Although we could show adherence of PU.1-deficient cells in response to PMA or fMLP, these cells failed to migrate when stimulated with IL-8, Groα, or fMLP. We were able to detect messages for IL-8 and fMLP chemokine receptors, suggesting that PU.1 loss does not abrogate receptor gene expression. Members of this family of receptors mediate their effects via a multitude of signaling molecules including heterotrimeric G proteins, phospholipase C, small GTP-binding proteins, phosphoinositol 3-kinase, and the MAP kinase cascade.40 The possibility of abnormalities in cell surface IL-8 and fMLP receptor expression, downstream signaling, or cellular processes governing motility in PU.1-deficient neutrophils has not been further explored at this time.

PU.1-deficient cells also failed to generate a respiratory burst. This phenomenon represents the conversion of molecular oxygen to the radical superoxide (O2−) that is mediated by the phagocyte-specific enzyme NADPH oxidase. O2− is the precursor to a number of potent oxidants (including H2O2, HOCl, and OH.) with antimicrobial activity.27 NADPH oxidase is composed of four subunits; two membrane components, p22 and gp91; and two cytoplasmic subunits, p47 and p67. Genes for these subunits are expressed early in myeloid development.41,42When the neutrophil receives an appropriate external stimulus, the preexisting component subunits become assembled on the membrane to form an active enzyme. Although PU.1-deficient cells lack some of the receptors that are used for initiating the respiratory burst (such as CD11b and G- and GM-CSF receptors), this cannot account for their failure to respond to PMA. Our studies demonstrate the absence of detectable messages for gp91phox, but not other subunits of NADPH oxidase, in PU.1-deficient neutrophils. Thus, our studies would suggest that a critical subunit of NADPH oxidase is absent, which, in turn, would prevent O2−generation. However, we cannot fully discount additional disruptions in the respiratory burst pathway caused by the absence of PU.1. The loss of gp91 is also reported in 60% of the cases of chronic granulomatous disease, a disorder that can be caused by mutations in any of the oxidase’s four subunits. These mutations typically result in absent or severely reduced expression of the mutated subunit, and affected people have ineffective phagocytes that lack respiratory burst activity.43 Our results show that PU.1 directly or indirectly affects gp91phox gene transcription. Although earlier promoter studies have suggested that PU.1 binding sites might not be present in the promoter of the gp91phox gene,44 recent studies on human neutrophils, monocytes, and B lymphocytes suggest that PU.1 is essential for transcription of the gp91phoxgene.45 Thus, our studies support a pivotal role for PU.1 in regulating the expression of early myeloid (M-CSF and G-CSF receptors and gp91phox ) as well as later neutrophil (lysozyme, gelatinase, and lactoferrin) genes.

The functions of phagocytosis and bacterial killing were also severely compromised in PU.1-deficient cells. Fc receptor-mediated (stimulated) phagocytosis was markedly reduced compared with normal phagocytosis, possibly because of the absence of CD11b, which has been shown to play an indirect but essential role in this process.46 Still, baseline (unstimulated) phagocytosis, which is not dependent on CD11b,46 by PU.1-deficient cells was below the level of normal neutrophils. Reduced uptake and reduced killing of live bacterial organisms by PU.1-deficient neutrophils was reflected in the higher recovery of viable bacteria after incubation with these cells. Defective bacterial killing may be a reflection of the absence of O2−, as it is documented that individuals with chronic granulomatous disease (that fail to produce this metabolite as a consequence of mutations in various subunits of NADPH oxidase) suffer from severe and repeated bacterial infections.43 However, the notion that considerable redundancy exists in the neutrophil’s antimicrobial defense system is supported by the ability of PU.1-deficient neutrophils to kill organisms despite their numerous deficiencies.

Similar to CD11b, myeloid growth factor receptors are also believed to mediate many functions of mature neutrophils. G-CSF receptor stimulation in particular is reported to stimulate arachidonic acid release and myeloperoxidase production, and prime mature neutrophils for activation. The number of receptors per cell for G- and GM-CSF increases with neutrophil maturation.11,47 Interestingly, G-CSF cytokine- and receptor-gene–disrupted mice were noted to have ineffective neutrophilopoiesis in response to infection, and to handle infection inefficiently; however, individual neutrophil functions were not assessed.35,36 GM-CSF cytokine- and receptor-deficient mice were also not specifically assessed for neutrophil functions but had resting and infection-challenged cell counts comparable with normal mice.37 38 These results indicate a role for these cytokines/receptors in neutrophil expansion, yet their role in neutrophil maturation and acquisition of functionality is not completely resolved. In PU.1-deficient mice, there is clearly defective neutrophil expansion. Additionally, however, individual functions of neutrophils as well as other indicators of neutrophil maturity such as specific granule gene expression are lacking. The failure of PMA to activate PU.1-deficient neutrophils is evidence for effects of the PU.1 mutation that are independent of CD11b or growth factor receptors, because phorbol esters activate neutrophils directly. Certainly the absence of CD11b and growth factor receptors contributes to the overall phenotype; however, none of the phenotypes of these individual “knockout” mice matches that of the PU.1-null mouse with respect to the neutrophil lineage. Thus, a simple arrest of otherwise normal development does not adequately describe PU.1-deficient neutrophils.

Recently, the genes for several other myeloid-specific transcription factors have been disrupted in mice. These factors, specifically AML1, c-myb, and C/EBPα, are proposed to be regulators of many of the same myeloid genes as PU.1, including the myeloid growth factor receptors. Whereas disruption of c-myb and AML1 causes severe defects in fetal liver hematopoiesis with marked reductions or loss of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors in that compartment,48,49C/EBPα disruption is far more selective with its effects limited to the granulocyte (neutrophil and eosinophil) lineages,50which is consistent with its pattern of expression. C/EBPα-null mice have circulating Sudan black+ Gr-1−myeloblast-like cells but no mature neutrophils in vivo at birth. In in vitro colony-forming assays, C/EBPα-null cells can develop comparable numbers of granulocyte-containing colonies, yet only immature granulocytes are present. These cells share a common molecular defect with PU.1-deficient cells in that they fail to express the G-CSF receptor and do not respond to this cytokine.50 Both transcription factors have previously been reported to regulate the G-CSF receptor promoter.6 Despite this deficiency, commitment to the neutrophil lineage occurs in C/EBPα-null mice as in PU.1-null mice. It is clear that molecular defects other than dysregulation of cytokine receptor gene(s) must exist in both of these models. Comparison of the neutrophil lineage cells generated by PU.1- and C/EBPα-null mice should yield valuable information regarding crucial differentiation-controlling genes in neutrophils.

In summary, we have shown that the absence of the PU.1 gene product results in the development of the neutrophil lineage to an abnormal and incompletely mature stage. In addition to their failure to express CD11b and G- and GM-CSF receptors, the cells that develop are defective in their ability to migrate in response to selected chemokines, to ingest particles, and to kill live bacteria. Superoxide production, critical for neutrophil function, does not occur in PU.1-deficient neutrophils, most likely because of their inability to express gp91phox. Furthermore, messages for specific granule components are undetectable, suggesting that in the absence of PU.1, neutrophils do not terminally differentiate, and/or do not regulate specific granule component genes. PU.1-null mice can only be maintained for approximately 2 weeks with antibiotic treatment before they die.12 This is most likely due in large part to lack of or ineffective response to infection by the neutrophils that do develop in vivo. Our results convincingly show that the PU.1 gene product is essential for normal neutrophil maturation and function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Kari Carver, the animal facility personnel at both the Burnham Institute and The Scripps Research Institute, and the secretarial assistance of Bonnie Towle. We also thank Drs Mary Dinauer and Bernie Babior for helpful discussions and Dr Michio Nakamura for sharing with us the results of his in-press manuscript. We thank Scott McKercher for critically reading the manuscript, and Greg Henkel for both critically reading the manuscript and affinity purification of the PU.1-GST antibody. This is publication 11314-IMM from The Scripps Research Institute.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK49886 (B.E.T.) and AI30656 (R.A.M.).

Address reprint requests to Bruce E. Torbett, PhD, Department of Immunology, IMM-7, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 N Torrey Pines Rd, La Jolla, CA 92037; e-mail: betorbet@scripps.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal