To The Editor:

In a recently published letter by O’Brien and Goldman1 in Blood, the investigators addressed clinical data that point to the benefits of using busulfan (BU) alone as a cytoreductive regimen in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) before autologous bone marrow transplantation (BMT). They argued that conditioning with BU alone leads to maximal cytoreduction with minimal treatment-related toxicity. This conclusion has a bearing on adding cyclophosphamide (CY) to BU treatment, because such a combination is often considered the conditioning regimen of choice for autologous as well as allogeneic BMT. Although the immune suppressive properties of CY may be necessary to overcome the problems of acute allograft rejection, it remains questionable whether this agent has any advantages when applied in the autologous BMT setting.

In this communication, we wish to support the arguments of O’Brien and Goldman1 by presenting data on mice that were transplanted with syngeneic or allogeneic bone marrow cells after BU conditioning with or without CY. These murine BMT models use a difference in donor and host glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (Gpi-1) as a means of determining the extent of short- and long-term erythroid chimerism. Previous studies in our laboratories have established that, although donor-type engraftment in the short-term is dependent on the depletion of committed cycling progenitor populations in the recipient bone marrow, it is the ability of conditioning therapy to ablate quiescent primitive stem cells (of high self-renewal) that largely determines the level of blood chimerism beyond 3 months after transplant.2-4 The data given in Fig1A show that a fractionated dose of BU is able to induce high levels of donor marrow engraftment of about 90% in the absence of an immunological barrier, whereas CY alone had minimal effects. These in vivo results are reflected in the amount of primitive stem cell killing by these agents as measured using the cobblestone area forming cell (CAFC) assay (CAFC day 35 subset survival of <0.001% and 81% for BU and CY, respectively). The addition of CY to BU treatment did not improve on the level of syngeneic engraftment. Indeed, there was a tendency for this combination to result in decreased chimerism levels and this difference was significant at all times after 4 weeks when BU was administered as a single dose of 50 mg/kg (data not shown) via mechanisms that are as yet unclear.

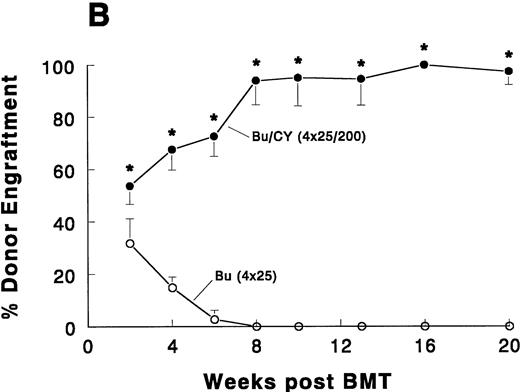

Syngeneic (A) and allogeneic (B) bone marrow engraftment after pretreatment with BU with or without CY. Male C57BL/6JIco (B6-Gpi-1b/Gpi-1b) mice (Iffa Credo, L’Arbresle, France), 12 to 16 weeks old and weighing 25 to 30 g, were used as recipients. Congenic C57BL/6J-Gpi-1a/Gpi-1a(B6-Gpi-1a) and BALB.B10 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbour, ME) were used as the source of syngeneic and H-2 compatible allogeneic donor bone marrow, respectively. Busulfan was injected intraperitoneally (IP) as a suspension in corn oil as fractionated doses (4 × 25 mg/kg) on 4 consecutive days. CY was administered (IP in phosphate-buffered saline, 200 mg/kg) 24 hours after (the last dose of) BU. BMT (106 bone marrow cells) was performed 24 hours after the last drug treatment or 48 hours after BU when CY was not in the regimen. Shown are the means (±SD, 4 to 6 mice per group) as percentages of Gpi-1a type erythroid chimerism up to 5 months after BMT. Asterisks indicate significance in Mann-Whitney-U test (*P < .01; **P < .05).

Syngeneic (A) and allogeneic (B) bone marrow engraftment after pretreatment with BU with or without CY. Male C57BL/6JIco (B6-Gpi-1b/Gpi-1b) mice (Iffa Credo, L’Arbresle, France), 12 to 16 weeks old and weighing 25 to 30 g, were used as recipients. Congenic C57BL/6J-Gpi-1a/Gpi-1a(B6-Gpi-1a) and BALB.B10 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbour, ME) were used as the source of syngeneic and H-2 compatible allogeneic donor bone marrow, respectively. Busulfan was injected intraperitoneally (IP) as a suspension in corn oil as fractionated doses (4 × 25 mg/kg) on 4 consecutive days. CY was administered (IP in phosphate-buffered saline, 200 mg/kg) 24 hours after (the last dose of) BU. BMT (106 bone marrow cells) was performed 24 hours after the last drug treatment or 48 hours after BU when CY was not in the regimen. Shown are the means (±SD, 4 to 6 mice per group) as percentages of Gpi-1a type erythroid chimerism up to 5 months after BMT. Asterisks indicate significance in Mann-Whitney-U test (*P < .01; **P < .05).

Very different results emerged from the use of allogeneic BMT, in which the immunological disparity conferred a rapid rejection of the donor cells and complete host marrow repopulation by 1 month after BU treatment alone (Fig 1B). In this case, the addition of CY produced dramatic results where it appeared to prevent the acute rejection and produce levels of allogeneic chimerism that were comparable with the syngeneic situation. The clear advantage of using CY with BU is consistent with the earlier pioneering work of Tutschka and Santos,5 6 who first demonstrated how this combination circumvented allograft rejection in allogeneic rat BMT models.

We are aware of the fact that these studies refer to an animal model and that our mice were not leukemic. However, it may be expected that diseases such as CML may be similarly unaffected by the addition of CY if the malignant cells share the same chemoresistance to the normal primitive stem cell counterpart that produces long-term chimerism. Therefore, these results are consistent with the hypothesis by O’Brien and Goldman in that the addition of CY in autologous BMT may not be beneficial in terms of clinical outcome and may carry the burden of unnecessary enhanced toxicities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by Grant No. EUR 95-1017 from the Dutch Cancer Society.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal