Abstract

Thrombopoietin (TPO) is a lineage-dominant hematopoietic cytokine that regulates megakaryopoiesis and platelet production. The major site of TPO biosynthesis is the liver. Despite easily detectable levels of liver TPO mRNA, the circulating TPO serum levels are very low. We have observed that translation of TPO mRNA is inhibited by the presence of inhibitory elements in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR). Alternative promoter usage and differential splicing generate at least three TPO mRNA isoforms that differ in the composition of their 5′-UTR. Using mutational analysis we show that physiologically the translation of these TPO mRNA isoforms is strongly inhibited by the presence of AUG codons, which define several short open reading frames (ORFs) in the 5′-UTR and suppress efficient initiation at the physiologic start site. The two regularly spliced isoforms, which account for 98% of TPO mRNA, were almost completely inhibited, whereas a rare splice variant that lacks exon 2 can be more efficiently translated. Thus, inhibition of translation of the TPO mRNA is an efficient mechanism to prevent overproduction of this highly potent cytokine.

THROMBOPOIETIN (TPO) is the primary regulator of megakaryopoiesis and platelet production.1 The major site of TPO production is the liver,2 but TPO mRNA is also found at lower abundance in the kidney,3 the spleen,4 and in bone marrow (BM) stromal cells.4,5 The normal serum concentration of TPO is very low, ranging between 0.5 and 2 pmol/L,6-8which was one of the factors hindering the purification of the protein for more than 40 years.9

TPO serum concentrations inversely correlate with the platelet and megakaryocyte mass.10,11 During thrombocytopenia, TPO production in liver and kidney is not regulated at the transcriptional level.12-14 It remains controversial whether transcriptional regulation can occur in the BM.4,15 A simple and elegant model of platelet autoregulation16,17that involves absorption of TPO by platelets through the TPO receptor, MPL, is supported by a large amount of experimental data.1,18 Consistently, mice deficient in mpl showed dramatically reduced platelet counts and elevated TPO serum levels.19 Furthermore, TPO-deficient mice displayed haploinsufficiency,20 indicating that in the heterozygous state the decrease in platelet mass cannot be compensated by increasing the TPO production from the remaining wild-type allele. This strongly argues against a “sensor for platelet mass” that would function analogous to the “oxygen sensor” for erythropoietin (EPO).21 However, certain clinical observations are difficult to explain by the simple version of the autoregulation model. In particular, some patients with reactive thrombocytosis display TPO serum concentrations too high for their platelet count,22 23 suggesting that under certain conditions TPO production might be upregulated by a mechanism independent of the platelet mass.

We have previously observed that the wild-type TPO mRNA is inefficiently translated in vitro and that a splicing mutation affecting the composition of the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) results in overproduction of TPO protein, causing hereditary thrombocythemia in a Dutch family.24 There are at least two mechanisms by which the 5′-UTR might repress translation.25 Both rely on the fact that the 40 S ribosomal subunit first binds to the cap structure at the 5′-end of a mRNA and then scans for the first AUG codon. The presence of stable stem loops between the cap structure and the first AUG can interfere with ribosomal scanning and has been shown to profoundly inhibit translation.26,27 Alternatively, the presence of AUG codons upstream of the actual start site (uAUG) can inhibit translation by causing premature initiation and thereby preventing the ribosome from initiating at the physiological start codon.28 The degree of inhibition depends on the sequence context of the uAUG29 and the length and phase of the resulting open reading frame (ORF) in respect to the protein coding sequence.30 The majority (90% to 95%) of eukaryotic mRNAs do not have uAUG codons in the 5′-UTR,29 whereas TPO belongs to the smaller class of mRNAs with the presence of uAUG in the 5′-UTR, which sometimes display translational regulation.31

Here we studied the translation of three naturally occurring TPO mRNA isoforms that are generated by alternative promoter usage and differential splicing and differ in the composition of their 5′-UTR, but not in the coding sequence. We performed mutational analysis and show that translation of these isoforms is inhibited by upstream AUG codons and not by secondary structure of the 5′-UTR. Furthermore, we found that the least abundant isoform, a splice variant32 that lacks the noncoding exon 2, was more efficiently translated than the two regularly spliced isoforms, introducing the possibility that regulation of alternative splicing may serve as an additional control mechanism for TPO production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA analysis.

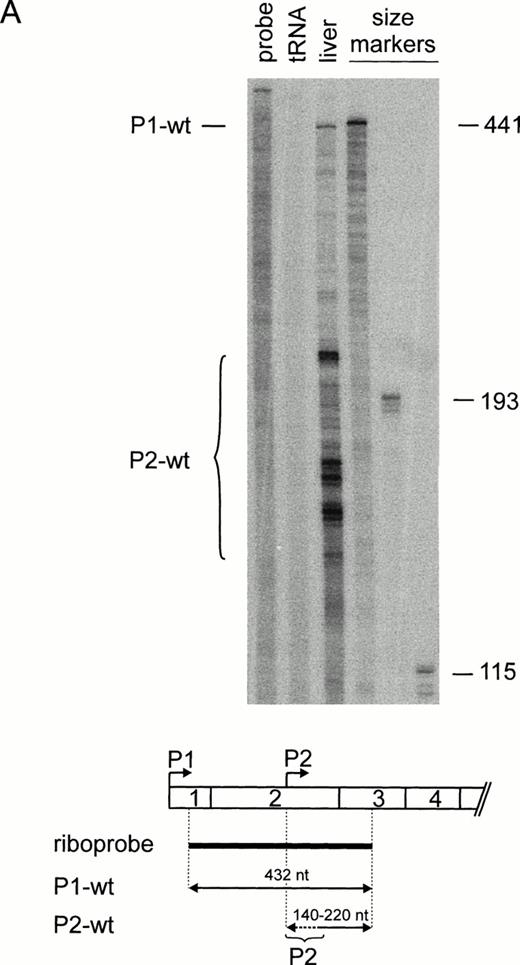

Ribonuclease protection analysis was performed as described.33 Total RNA from human liver was prepared by the acid phenol method34 and 15 μg was used for analysis. For the detection of P1 and P2 TPO transcripts we generated a riboprobe corresponding to nucleotides 49 to 480 of the TPO cDNA sequence, as derived from the published TPO genomic sequence.32 This riboprobe protects a 432-nucleotide (nt) fragment for TPO P1 transcripts and fragments ranging from 142 to 212 nt for P2 transcripts. A second riboprobe corresponding to P1 TPO mRNA that lacks exon 2 (P1ΔE2) was constructed using the primers 5′-CCGCCCGAAGGATGAAGAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGCAGGCAGCAGGACAGGTG-3′ (antisense). This riboprobe protects a 386-nt fragment for P1ΔE2 and a 336-nt fragment for the full-length P1 and P2 transcripts. As size markers, RNAs transcribed in vitro from cDNA constructs corresponding to the different 5′-UTR were used. Radioactive bands were separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels and quantitated using a PhosphorImager 425 (Molecular Dynamics Inc, Sunnyvale, CA).

Site-directed mutagenesis of upstream AUG codons.

Upstream AUG codons were mutated by recombinant polymerase chain reaction (PCR).35 The same antisense primer, 5′-CCACGAGTTCCATTCAAGAG-3′ (nucleotide 1322), was used in combination with various individual sense primers in all PCR reactions. The sense primers for P1 constructs were 5′-CGCAGATCTGCCGAAGACTTGTCTTTAAAGCCGACAACG-3′ (mutated uAUG 1,2), or 5′-CGCAGATCTGATGAAGACTTGTCTTTAAAGATGACAACG-3′ (wild-type uAUG 1,2), and the sense primers for P2 constructs were 5′-CAGAGATCTGTACGACCTGCTGCTGT-3′ (mutated uAUG 5), or 5′-CAGAGATCTGTATGACCTGCTGCTGT-3′ (wild-type uAUG 5). A unique BglII site for subcloning (underlined) was introduced into each of the 5′ sense primers. To mutate internal uAUG codons in the 5′-UTR by recombinant PCR,35 we used the following primer combinations: uAUG 3: 5′-GTTGCCCGGGTCCAGGAAAAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTTTTCCTGGACCCGGGCAAC-3′ (antisense); uAUG 4: 5′-CAGGAAAAGCCGGATCCCCC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGGGGATCCGGCTTTTCCTG-3′ (antisense); uAUG 5: 5′-GCAGGCGTACGACCTGCTGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCAGCAGGTCGTACGCCTGC-3′ (antisense); uAUG 6: 5′-CACCGCCACGCGTCTTCCTA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TAGGAAGACGCGTGGCGGTG-3′ (antisense); uAUG 7: 5′-GCCGCCTCCTTGGCCCCAGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCTGGGGCCAAGGAGGCGGC-3′ (antisense). To delete the 21-bp GUG repeat a unique Sac I site (underlined) was introduced in each of the two primers 5′-GAGCCGCGGACCCTGGTCCAGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACACCGCGGAGAAGATTTGGAT-3′ (antisense) flanking the GUG repeat. The PCR products were digested with Sac I and religated. Combinations of these primers were used in several rounds of recombinant PCR to generate TPO 5′-end fragments carrying mutations in the 5′-UTR (detailed protocol available upon request). These fragments were digested with BglII andPst I (unique endogenous restriction site at position 922 of TPO cDNA) and ligated as a three-part ligation together with aPst I-Xba I fragment representing the 3′-portion of the TPO cDNA and a BamHI-Xba I–digested pcDNA-1/Amp (Invitrogen Corp, San Diego, CA). To prevent artifacts in the translation assays, all junctions were designed so that no new AUG codons were generated by insert ligation between the T7 promoter and the TPO 5′-UTR. All final constructs were sequenced on an Applied Biosystems 373 DNA sequencer (Perkin Elmer Corp, Foster City, CA).

In vitro transcription and translation.

The constructs in pcDNA1-Amp were linearized with Xba I and 2 μg of linearized DNA was used as templates for in vitro RNA synthesis for 1 hour at 37°C using T7 RNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The products were digested with DNaseI for 15 minutes at 37°C, extracted with phenol/chloroform, and ethanol-precipitated. One-half microgram of each TPO mRNA isoform was translated for 1 hour at 30°C in reticulocyte lysate in the presence of35S-Methionine according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega Corp, Madison, WI). Radioactive proteins were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and visualized on a PhosphorImager 425 (Molecular Dynamics Inc).

Cell culture and TPO bioassay.

RESULTS

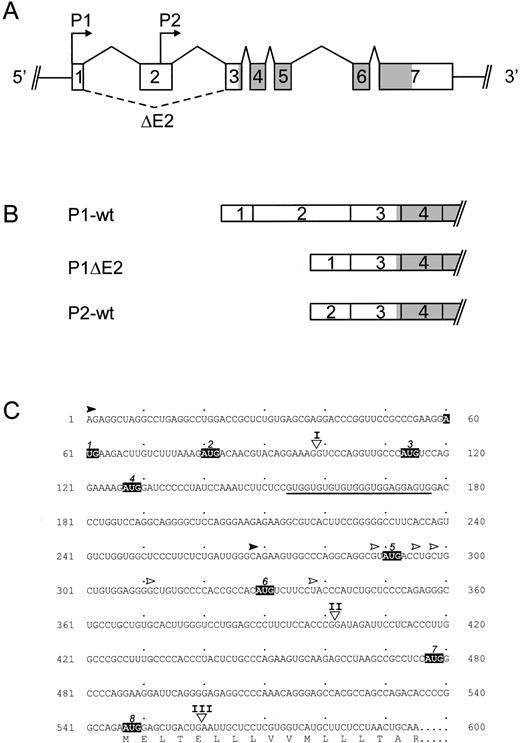

Because our previous work suggested that the 5′-UTR of the TPO mRNA contains elements that inhibit translation,24 we examined whether regulation of TPO translation might be a general mechanism for controlling TPO protein levels. The TPO 5′-UTR is encoded by exons 1, 2, and a large part of exon 3.32 Usage of alternative promoters (P1 and P2) and differential splicing generate TPO mRNAs that differ in the length and composition of their 5′-UTR (Fig 1A through C). To assess the relative contribution of TPO mRNA isoforms to the overall production of TPO protein, we first determined their relative abundance in human liver RNA by a ribonuclease (RNase) protection assay. Using a riboprobe that can distinguish between P1 and P2 transcripts (Fig 2A), we found a weak full-length protected band corresponding to P1 transcripts, and several shorter fragments corresponding to the multiple transcriptional start sites described for P237-39 (Fig 2A). Quantitation of these radioactive bands showed that in human liver RNA approximately 10% of all transcripts are synthesized from P1, whereas 90% originate from P2. The same result was obtained with RNA from three independent livers (not shown). The majority of P1 transcripts contained exons 1 through 3 (P1-wt). An alternatively spliced P1 transcript that lacks exon 2 (P1ΔE2) was detectable using a second riboprobe (Fig 2B). The identity of this band was confirmed by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and sequencing (not shown). The majority of P2 transcripts contain exons 2 through 5 (Fig 2A and B). Quantitation of the bands in Fig 2A and B showed that the P2-wt transcripts accounted for approximately 90%, P1-wt for 8%, and P1ΔE2 for 2% of total TPO mRNA.

(A) Structure of the human TPO gene. Exons are drawn as boxes and the protein coding region is shaded. Arrows mark the start sites for promoter 1 and 2 (P1 and P2). Solid lines connecting exons indicate normal splice events, dashed lines alternative splice events. ▵E2, exon 2 skipping. (B) Exon composition of the TPO mRNA splice variants. P1-wt and P2-wt, the full-length TPO mRNA transcribed from P1 or P2, respectively; P1▵E2, alternatively spliced TPO mRNA with exon 2 skipping. (C) Position of uAUG in the TPO 5′-UTR. The full-length mRNA sequence of the TPO 5′-UTR beginning with the P1 start site, as determined by Chang et al,32 is shown. Upstream AUG codons are boxed and numbered in the order as they appear. Translation of wild-type TPO protein starts at the eighth AUG (AUG 8). The deduced amino acid sequence is shown in the one-letter code. A stretch of GUG triplets is underlined. Triangles and Roman numerals mark the locations of introns.32 Filled arrowhead, P1 start site mapped by Chang et al32; gray arrowhead, P2 start site determined by Sohma et al37; open arrowheads, P2 start sites mapped by Kamura et al38 and Gurney et al.39

(A) Structure of the human TPO gene. Exons are drawn as boxes and the protein coding region is shaded. Arrows mark the start sites for promoter 1 and 2 (P1 and P2). Solid lines connecting exons indicate normal splice events, dashed lines alternative splice events. ▵E2, exon 2 skipping. (B) Exon composition of the TPO mRNA splice variants. P1-wt and P2-wt, the full-length TPO mRNA transcribed from P1 or P2, respectively; P1▵E2, alternatively spliced TPO mRNA with exon 2 skipping. (C) Position of uAUG in the TPO 5′-UTR. The full-length mRNA sequence of the TPO 5′-UTR beginning with the P1 start site, as determined by Chang et al,32 is shown. Upstream AUG codons are boxed and numbered in the order as they appear. Translation of wild-type TPO protein starts at the eighth AUG (AUG 8). The deduced amino acid sequence is shown in the one-letter code. A stretch of GUG triplets is underlined. Triangles and Roman numerals mark the locations of introns.32 Filled arrowhead, P1 start site mapped by Chang et al32; gray arrowhead, P2 start site determined by Sohma et al37; open arrowheads, P2 start sites mapped by Kamura et al38 and Gurney et al.39

Differential promoter usage and alternative splicing of TPO pre-mRNA. (A) Ribonuclease protection analysis of human liver RNA. (Top) Lanes 1 and 2, undigested riboprobe and tRNA control. P1 transcripts (P1-wt) account for approximately 10% of TPO mRNA. Note that P2 transcripts (P2-wt) initiate at multiple start sites. In vitro transcribed sense mRNAs corresponding to different 5′-UTR were used as RNA size markers (lanes 4 through 6). Numbers at the right indicate length of the RNA size markers in nucleotides. (Bottom) Length and position of the riboprobe (thick line) and the protected fragments (arrows) with respect to the TPO mRNA 5′-end. (B) Assessment of exon 2 skipping (P1▵E2) by ribonuclease protection. Annotation as in (A).

Differential promoter usage and alternative splicing of TPO pre-mRNA. (A) Ribonuclease protection analysis of human liver RNA. (Top) Lanes 1 and 2, undigested riboprobe and tRNA control. P1 transcripts (P1-wt) account for approximately 10% of TPO mRNA. Note that P2 transcripts (P2-wt) initiate at multiple start sites. In vitro transcribed sense mRNAs corresponding to different 5′-UTR were used as RNA size markers (lanes 4 through 6). Numbers at the right indicate length of the RNA size markers in nucleotides. (Bottom) Length and position of the riboprobe (thick line) and the protected fragments (arrows) with respect to the TPO mRNA 5′-end. (B) Assessment of exon 2 skipping (P1▵E2) by ribonuclease protection. Annotation as in (A).

One mechanism by which the 5′-UTR might inhibit translation is aberrant initiation at uAUG codons.28 The 5′-UTR sequence of the longest TPO mRNA transcript (P1-wt) contains seven uAUG codons (Fig 1C), whereas the alternative TPO isoforms display a reduced number and different composition of uAUG codons. An alternative mechanism of how the efficiency of translation might be reduced is the presence of stem loops in the 5′-UTR, which might interfere with ribosomal scanning.26,27 Using the Zuker algorithm,40 we found that none of the TPO mRNA isoforms is predicted to form stem loops sufficiently stable to inhibit ribosomal scanning.26 27

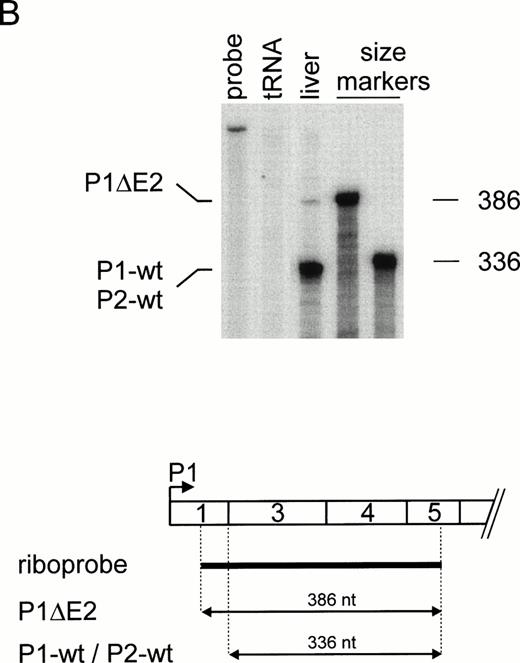

To more directly test whether the presence of uAUG codons in the 5′-UTR of the TPO mRNA isoforms is responsible for the inhibition of translation, we introduced point mutations in individual uAUG codons by site-directed mutagenesis (Fig 3). Several of these uAUGs are in a favorable sequence context for initiation, as defined by Kozak.29 To assure that the mutations will prevent the ribosome from initiating, two bases of the uAUG codon were altered in most positions (Fig 3).

Summary of the site directed mutagenesis of uAUG codons. (Top) The Kozak consensus sequence favorable for ribosomal initiation.29 The most critical residues, positions −3 and +4, are typed in bold characters. Left column: sequence context of TPO uAUG codons. Residues in positions −3 and +4 that match the Kozak consensus are typed in boldface. Right column: mutations in uAUG sequences designed to inactivate ribosomal initiation.

Summary of the site directed mutagenesis of uAUG codons. (Top) The Kozak consensus sequence favorable for ribosomal initiation.29 The most critical residues, positions −3 and +4, are typed in bold characters. Left column: sequence context of TPO uAUG codons. Residues in positions −3 and +4 that match the Kozak consensus are typed in boldface. Right column: mutations in uAUG sequences designed to inactivate ribosomal initiation.

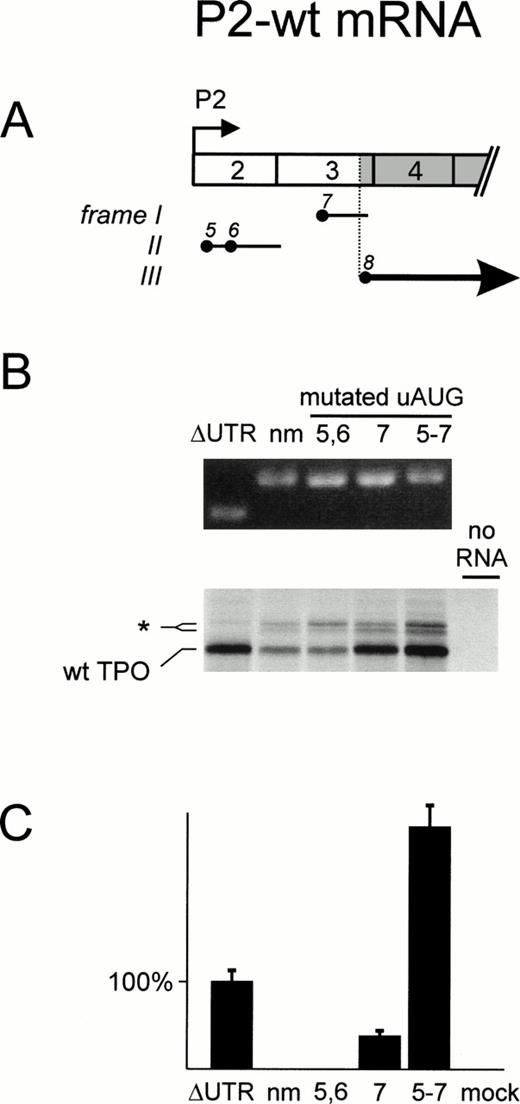

We analyzed each isoform individually. First, we examined mRNAs that originate from P2 and represent the majority of TPO transcripts. Transcription initiation occurs at multiple start sites in exon 2, resulting in mRNA molecules with a variable length of the 5′-UTR and different numbers of uAUG codons. The longest P2 transcripts37 retain uAUG 5, 6, and 7, whereas the shortest contain only uAUG 7 (see Fig 1C). The three uAUG codons of P2-wt mRNA define two ORFs upstream of the eighth AUG (AUG 8), the physiologic TPO initiation codon (Fig 4A). To include all possible uORFs, we designed our cDNA constructs to start upstream of uAUG 5. Together, these ORFs strongly inhibited wild-type TPO protein production, as measured by an in vitro transcription-translation assay (Fig 4B, lane 2). Consistently, no TPO bioactivity was detectable in supernatants of COS cells transfected with P2-wt cDNA (Fig 4C, lane 2). Deletion of all but the last seven nucleotides upstream of AUG 8 (ΔUTR) improved translation and resulted in secretion of TPO bioactivity into COS supernatants (Fig 4B and C, lanes 1). Removal of uAUG 5 and 6 did not enhance translation (lanes 3), showing that uAUG 7 is sufficient to inhibit TPO production. In contrast, the absence of uAUG 7 improved translation in reticulocyte lysate to levels similar to the ΔUTR mRNA. TPO production in COS cells was also improved (Fig 4B and C, lanes 4), although not to the same degree as for the ΔUTR mRNA. This discrepancy was not due to a difference in transfection efficiency, because equal amounts of human TPO mRNA were detected by Northern blot analysis (not shown). Possible explanations might be that there are differences between COS cells and reticulocyte lysates in the efficiency of initiation at uAUG 5 and 6 and/or the re-initiation at AUG 8. Finally, inactivation of all uAUGs resulted in more efficient in vitro translation and COS TPO production than ΔUTR (Fig 4B and C, lanes 5). This result was obtained in two independent transfections and at present we do not understand why the addition of a 258-nt long 5′-UTR without uAUGs improved TPO production to levels higher than ΔUTR. Nevertheless, inhibition of translation is primarily mediated by the presence of uAUG codons and is not due to formation of RNA secondary structures.

Analysis of the translational efficiency of TPO P2-wt transcripts in vitro and in transfected COS cells. (A) Exon composition of the TPO mRNA. The TPO protein coding region is shown in gray. The uAUG triplets (filled circles) are numbered in the order they appear in the P1-wt transcript and the resulting ORFs (horizontal solid lines) are placed in the three possible reading frames (Roman numerals). The thick solid line with arrowhead represents the ORF encoding TPO protein. (B) In vitro transcription translation analysis. Equal amounts of in vitro transcribed TPO mRNA variants (top) were translated in vitro in reticulocyte lysate in the presence of35S-methionine (bottom). ▵UTR, mRNA with deletion of the entire 5′-UTR; nm, mRNA with no mutations in the 5′-UTR; numbers above individual lanes indicate the position of mutated uAUGs. The protein bands in the bottom panel were identified as: wt TPO, initiation at the physiological start site (AUG 8); asterisk, cryptic non-AUG initiation within exon 3. (C) TPO production and secretion by transfected COS cells. Presence of TPO in COS cell supernatants was determined by bioassay. Mock transfected COS cells were set as background and cells transfected with a ▵UTR expression construct as 100%. Bars indicate the median ± SEM of triplicates.

Analysis of the translational efficiency of TPO P2-wt transcripts in vitro and in transfected COS cells. (A) Exon composition of the TPO mRNA. The TPO protein coding region is shown in gray. The uAUG triplets (filled circles) are numbered in the order they appear in the P1-wt transcript and the resulting ORFs (horizontal solid lines) are placed in the three possible reading frames (Roman numerals). The thick solid line with arrowhead represents the ORF encoding TPO protein. (B) In vitro transcription translation analysis. Equal amounts of in vitro transcribed TPO mRNA variants (top) were translated in vitro in reticulocyte lysate in the presence of35S-methionine (bottom). ▵UTR, mRNA with deletion of the entire 5′-UTR; nm, mRNA with no mutations in the 5′-UTR; numbers above individual lanes indicate the position of mutated uAUGs. The protein bands in the bottom panel were identified as: wt TPO, initiation at the physiological start site (AUG 8); asterisk, cryptic non-AUG initiation within exon 3. (C) TPO production and secretion by transfected COS cells. Presence of TPO in COS cell supernatants was determined by bioassay. Mock transfected COS cells were set as background and cells transfected with a ▵UTR expression construct as 100%. Bars indicate the median ± SEM of triplicates.

The results for the longer transcripts initiating at P1 are summarized in Fig 5A through C. The seven uAUG codons of P1-wt define five ORFs upstream of AUG 8 (Fig 5A). Together, these ORFs almost completely inhibited wild-type TPO protein production in vitro (Fig 5B, lane 2). A strong, slower migrating band corresponding to initiation at uAUG 4 was observed. Using the algorithm by Nielsen et al,41 the stretched amino terminus of this protein was predicted to be nonfunctional as a signal peptide. Consistently, no TPO bioactivity was detectable in supernatants of COS cells transfected with P1-wt cDNA (Fig 5C, lane 2). Individual mutations in uAUG 4 or uAUG 7 slightly improved translation without producing measurable TPO in COS supernatants (lanes 3 and 4), suggesting that each of these ORFs is sufficient to repress TPO production. The double mutation in uAUG 4 and uAUG 7 further relieved repression of translation, but resulted in TPO bioactivity only slightly above background (lane 5). A similar difference between the reticulocyte lysate and COS cell assay systems was already observed for the P2-wt construct also lacking uAUG 7 (Fig4). When we simultaneously mutated all seven uAUGs, we observed improved translation and secretion of TPO protein (lanes 6). The efficiency of translation and secretion was further improved to levels comparable to the ΔUTR construct when we deleted a stretch of four in-frame GUG codons located just 3′ of uAUG 4 (lanes 7), which appear to function as cryptic ribosomal initiation sites.42

Analysis of the translational efficiency of TPO P1 transcripts in vitro and in transfected COS cells. Annotation as in Fig4. (A through C) Full-length P1 transcript (P1-wt); (D through F) transcripts with exon 2 skipping (P1▵E2). (A and D) Exon composition of the TPO mRNA isoforms. Open rectangle, GUG repeat. (B and E) In vitro transcription translation analysis. (Top) ▵GUG, mRNA with deletion of the cryptic GUG initiation sites. (Bottom) uAUG 4 and GUG, proteins with extended amino terminus through in-frame initiation at the fourth uAUG or the GUG repeat, respectively. (C and F) TPO production and secretion by transfected COS cells.

Analysis of the translational efficiency of TPO P1 transcripts in vitro and in transfected COS cells. Annotation as in Fig4. (A through C) Full-length P1 transcript (P1-wt); (D through F) transcripts with exon 2 skipping (P1▵E2). (A and D) Exon composition of the TPO mRNA isoforms. Open rectangle, GUG repeat. (B and E) In vitro transcription translation analysis. (Top) ▵GUG, mRNA with deletion of the cryptic GUG initiation sites. (Bottom) uAUG 4 and GUG, proteins with extended amino terminus through in-frame initiation at the fourth uAUG or the GUG repeat, respectively. (C and F) TPO production and secretion by transfected COS cells.

Given the high degree of translational repression of TPO P1 mRNA, it is conceivable that low abundant splice variants that lack one or several uAUG codons might overproportionally contribute to TPO protein production. Therefore, we investigated P1ΔE2 transcripts, which only retain uAUG 1, 2, and 7 in their 5′-UTR (Fig 5D). P1ΔE2 mRNA is translated more efficiently into TPO protein than P1-wt mRNA (compare lanes 2 of Fig 5B and E), although not as efficient as ΔUTR mRNA (Fig5E, lanes 1 and 2). Removal of uAUG 1 and 2 did not improve TPO production (lanes 3), but removal of uAUG 7 enhanced translation as efficiently as removal of the entire UTR (lanes 4) or a construct with mutations in all uAUGs (lanes 5). For all P1ΔE2 mutants, the in vitro translation results correlate well with the corresponding TPO secretion by transfected COS cells (Fig 5F).

DISCUSSION

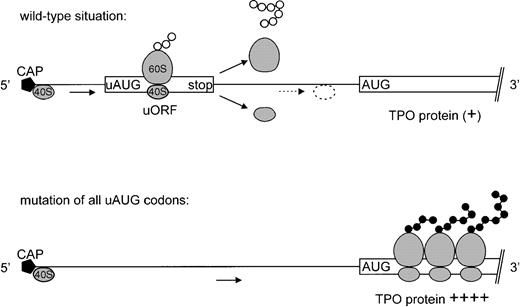

Our results show that the translation of TPO mRNA is physiologically almost completely inhibited by the presence of uAUG codons in the 5′-UTR. According to the ribosomal scanning model,28these uAUGs lead to premature ribosomal initiation followed by translation of a short peptide and partial dissociation of the ribosome from the mRNA when a stop codon is encountered (Fig 6). Removal of all uAUG codons by point mutations improved translation to the same degree as deletion of the entire 5′-UTR, indicating that the formation of RNA secondary structures does not play a major role in repressing TPO mRNA translation (Figs 4 and 5). Mutation of individual uAUG codons showed that uAUG 7 is a potent inhibitor of translation, most likely because the corresponding uORF extends past the physiological start site, AUG 8. Interestingly, this uORF is conserved between human,2mouse,43 and rat.44 Additional strong inhibition is conferred by uAUG 4 in P1-wt and by uAUG 5 and 6 in P2-wt transcripts, whereas uAUGs 1, 2, and 3 had only minor effects. Thus, the strong inhibition of translation by multiple uAUGs in the 5′-UTR of the TPO mRNA constitutes a reliable mechanism for preventing overproduction of this highly potent cytokine by the liver. Indeed, loss of this inhibition has been shown to cause thrombocytosis in a family with hereditary thrombocythemia,24 and it will be interesting to determine whether the same mechanism is involved in the pathogenesis of other families with thrombocythemia. Moreover, this translational inhibition appears to be used in other members of the helical cytokine family, eg, interleukin-7 (IL-7) and IL-15.45 46

Effect of upstream ORFs on TPO mRNA translation. (Top) Simplified drawing of TPO mRNA with only one uORF in the 5′-UTR followed by the TPO coding region (open boxes). According to the ribosomal scanning model, the 40 S ribosomal subunit will bind the cap structure at the 5′ end of the mRNA and scan the mRNA until it encounters the first AUG, where a functional ribosome is assembled. The ribosome will initiate translation and synthesize a short peptide until a stop codon is reached. Here the ribosome dissociates from the mRNA. This will prevent the ribosome from reaching the physiological TPO start codon. However, a minor proportion of 40 S subunits may remain associated with the mRNA and continue scanning for a downstream AUG. (Bottom) TPO 5′-UTR with point mutations in all uAUG codons will allow the 40 S subunit to reach the physiological start site more efficiently and initiate translation of the TPO protein.

Effect of upstream ORFs on TPO mRNA translation. (Top) Simplified drawing of TPO mRNA with only one uORF in the 5′-UTR followed by the TPO coding region (open boxes). According to the ribosomal scanning model, the 40 S ribosomal subunit will bind the cap structure at the 5′ end of the mRNA and scan the mRNA until it encounters the first AUG, where a functional ribosome is assembled. The ribosome will initiate translation and synthesize a short peptide until a stop codon is reached. Here the ribosome dissociates from the mRNA. This will prevent the ribosome from reaching the physiological TPO start codon. However, a minor proportion of 40 S subunits may remain associated with the mRNA and continue scanning for a downstream AUG. (Bottom) TPO 5′-UTR with point mutations in all uAUG codons will allow the 40 S subunit to reach the physiological start site more efficiently and initiate translation of the TPO protein.

TPO mRNA is transcribed from two promoters resulting in two major mRNAs, P1-wt and P2-wt, and an alternatively spliced isoform, P1ΔE2.32,37,38 We confirmed that P2 transcripts initiate at multiple transcriptional start sites.37-39 In contrast to a previous report by Kamura et al,38 who concluded that P1 transcripts were barely detectable in the adult liver, we found that approximately 10% of liver TPO mRNA originated from P1 (Fig 2). Thus, P1 transcripts might significantly contribute to the TPO protein production. Analysis of translational efficiency showed that the TPO mRNA isoforms were strongly inhibited by uORFs. However, the rare splice variant P1ΔE2 produced more TPO than the P1-wt and P2-wt transcripts (Figs 4 and 5). This opens the possibility that modulating the proportion of P1ΔE2 transcripts by differential splicing might constitute a means to augment TPO production in situations of increased platelet demand. Because alternative splicing would not change the abundance of total TPO mRNA, such a mechanism would be compatible with the observation that TPO mRNA in liver, kidney, and spleen is not regulated at the transcriptional level.12-14

Preferential usage of alternatively spliced mRNA variants in response to interferon-γ and lipopolysaccharide have been reported for IL-1547 and in response to phorbol esters for CD44.48 It is conceivable that selection of translationally more efficient TPO mRNA isoforms in response to proinflammatory cytokines or other extracellular signals might account for the high TPO serum levels in many patients with reactive thrombocytosis23 and, thus, constitute an additional mechanism in the regulation of platelet production. However, testing this hypothesis in human patients will be difficult because of limited availability of these tissues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank David C. Seldin and Michael Altmann for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (32-35503.92, 31-46857.96) and Schweizerische Krebsliga (KFS287-2-1996) to R.C.S., and from the Swiss National Science Foundation (3135-040025.94) and the Roche Research Foundation (96-240) to A.W.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Radek C. Skoda, MD, Biozentrum, University of Basel, Klingelbergstrasse 70, CH-4056 Basel, Switzerland; e-mail:skoda@ubaclu.unibas.ch.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal