Hemoglobinopathies, such as β-thalassemias and sickle cell anemia (SCA), are among the most common inherited gene defects. Novel models of human erythropoiesis that result in terminally differentiated red blood cells (RBCs) would be able to address the pathophysiological abnormalities in erythrocytes in congenital RBC disorders and to test the potential of reversing these problems by gene therapy. We have developed an in vitro model of production of human RBCs from normal CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells, using recombinant growth factors to promote terminal RBC differentiation. Enucleated RBCs were then isolated to a pure population by flow cytometry in sufficient numbers for physiological studies. Morphologically, the RBCs derived in vitro ranged from early polylobulated forms, resembling normal reticulocytes to smooth biconcave discocytes. The hemoglobin pattern in the in vitro-derived RBCs mimicked the in vivo adult or postnatal pattern of β-globin production, with negligible γ-globin synthesis. To test the gene therapy potential using this model, CD34+ cells were genetically marked with a retroviral vector carrying a cell-surface reporter. Gene transfer into CD34+ cells followed by erythroid differentiation resulted in expression of the marker gene on the surface of the enucleated RBC progeny. This model of human erythropoiesis will allow studies on pathophysiology of congenital RBC disorders and test effective therapeutic strategies.

MOLECULAR DEFECTS that cause sickle cell anemia (SCA) and the other common hemoglobinopathies have been well characterized.1-5 Genetic correction of hematopoietic stem cells with adequate expression of the inserted gene product in the defective red blood cells (RBCs; gene therapy) could revolutionize treatment of congenital RBC defects. Novel models of human erythropoiesis that result in terminally differentiated RBCs would be able to address the pathophysiological abnormalities in erythrocytes in congenital RBC diseases and to test the potential of reversing these problems by gene therapy.

The most commonly available in vitro assays of erythropoiesis from CD34+ progenitor cells are based on semi-solid medium colony-forming assays, which result in colonies consisting of nucleated erythroid cells. These erythroid colonies are either the early erythoid progenitors (burst- and colony-forming unit-erythroid [BFU-E]) or the late erythroid progenitors (colony-forming unit-erythroid [CFU-E]).6,7 Most of the in vitro liquid cultures from CD34+ progenitor cells are limited by the production of heterogeneous mixtures of mainly myeloid cells with few erythroid cells. Terminal erythroid differentiation has been reported when peripheral blood mononuclear cells are initially cultured in semi-solid media containing different growth factors for about 1 week, and then the cells (enriched in erythroid precursors) are transferred to a liquid culture containing erythropoietin (Epo) and grown under reduced oxygen concentrations.8-10 However, generation and isolation of terminally differentiated enucleated RBCs from highly purified human CD34+ progenitor cells in a single-step liquid culture system in vitro has not been previously described.

In this study, we report an in vitro model for production of human erythrocytes from purified human CD34+ progenitor cells in liquid culture followed by isolation of the enucleated erythrocytes by flow cytometry. Erythrocytes generated in this model showed an adult pattern of β-globin production. Gene transfer into CD34+cells followed by erythroid differentiation resulted in expression of the marker gene on the surface of the enucleated RBC progeny.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of CD34+ cells and culture conditions.

CD34+ progenitor cells were obtained from normal human bone marrow aspirates, from umbilical cord blood collected after normal deliveries, or from peripheral blood cells or bone marrow from patients with homozygous sickle cell disease. Use of all samples was approved by the Committee on Clinical Investigations at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles (Los Angeles, CA). Light-density mononuclear cells were obtained by centrifugation on ficoll-hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), as previously described.11 12 The accompanying RBCs were lysed by suspending the mononuclear cell pellet in Ortholysis buffer (Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Inc, Raritan, NJ). The mononuclear cells were then enriched for CD34+ cells by two cycles of positive selection using anti-CD34 antibody and immunomagnetic beads (typically to >90% to 95% purity) using Mini-MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). CD34+ cells were then cultured at a density of 105 cells/mL in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM; GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), 1% deionized bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St Louis, MO), 10−4 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, 10−6 mol/L hydrocortisone, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mmol/Ll-glutamine with the following recombinant cytokines: 10 U/mL of recombinant human (rH) Epo (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), 0.001 ng/mL rH granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and 0.01 U/mL rH interleukin-3 (IL-3; Immunex Corp, Seattle, WA) and incubated in 5% CO2at 37°C.

Antibody labeling and flow cytometry.

Erythroid cultures were harvested after 3 weeks. The cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in Hoechst buffer (IMDM containing 1% fetal calf serum [FCS] and 10 μg/mL of Hoechst 33342 [Sigma]) at a concentration of 106 cells/mL and incubated at 37°C for 90 minutes, shielded from light. The cells which were negative for fluorescence with the Hoechst dye were sorted using a dual argon/UV laser on a FACS Vantage flow-cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The Hoechst dye was excited with the 351 to 364 nm UV laser set to 50 mW and its fluorescence was measured using a 450/20 nm band pass filter (Omega Optical Inc, Brattleboro, VT). A 505-nm short pass dichroic mirror was used to separate emission wavelengths.13

For concomitant staining for surface markers, cells stained with Hoechst 33342 were pelleted, suspended at a concentration of 106 cells/100 μL Hoechst buffer at 4°C, and incubated with 6 μL of human Ig (10 mg/mL; Sandoz, East Hanover, NJ) for 20 minutes to block nonspecific antibody binding. Cells were then incubated for 20 minutes with 15 μL of biotin-labeled antibody to rat tNGFR, MC192 (0.1 μg/mL; Oncogene Science, Uniondale, NY) and then washed twice with PBS to remove excess antibody. Cells were then stained with 5 μL of phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled strepavidin (Caltag, San Francisco, CA) for 20 minutes, washed twice in PBS to remove excess secondary antibody, resuspended in Hoechst buffer, and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antihuman glycophorin A antibody (Immunotech, Marseille, France) for an additional 20 minutes. After 20 minutes of incubation, cells were washed to remove excess antiglycophorin antibody and resuspended in the Hoechst buffer before flow cytometry. FITC and PE emissions were measured using standard 530/30 and 575/26 dichroic filters. The presence or absence of Hoechst fluorescence was used to separate enucleated erythrocytes from the nucleated erythroid cells in the culture.

RBC volume determinations.

Mean cell volumes and volume distribution were determined using an aperture-impedence cell-sizing device, the Coulter counter (Coulter, Miami, FL).

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses of globin chains.

The types of globin chains produced in the erythrocytes derived in vitro from CD34+ cells and control blood samples were resolved by reverse-phase HPLC on a 4.6 × 250 mm large pore C4 column (Vydac Separations Group, Inc, Hisperia, CA) with a 44% to 56.5% linear gradient between mixtures of 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1 mL/min on a Beckman system Gold with Solvent module 125 and Detector module 166 set at 220 nm (Beckman Instrument, Inc, Fullerton, CA). Hemolysates were made by lysing 106 erythrocytes/sample in 10 μL of HPLC grade water for 10 minutes. The hemolysate was mixed with 40 μL of aqueous acetonitrile and centrifuged at 70,000g for 3 minutes to remove membranes. Twenty microliters of the hemolysate containing approximately 1 μg of hemoglobin was used for each run. The same number of umbilical cord blood RBCs and adult peripheral blood RBCs were used as controls.

Construction and packaging of the retroviral vectors.

The truncated rat nerve growth factor receptor (tNGFR) cDNA was used as a cell surface reporter gene in a Moloney murine leukemia retroviral vector backbone. Details of truncation of the rat NGFR cDNA have been described previously.14 A Pvu II-EcoRI fragment of the tNGFR cDNA was cloned into the XbaI-EcoRI sites of the LXSN vector backbone.15 The construct was transfected into PA317 cells and viral supernatant from L-tNGFR-SN PA317 cells was used to infect PG13 producer cells (obtained from American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Rockville, MD),16 as previously described.14 All producer cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; GIBCO) with 10% FCS. A high-titer clone of L-tNGFR-SN PG13 cells (clone 9), with a viral titer of 1 to 2 × 106infectious units/mL, was derived by limiting dilutions and FACS analyses.14 Viral supernatants from the L-tNGFR-SN (clone 9) were harvested after 48 hours of culture of confluent monolayers in DMEM with 10% FCS at 32°C, were filtered through 0.45-μm filters, and were used for CD34+ cell transductions.

Transduction of CD34+ cells.

CD34+ cells were suspended at a density of 105cells/mL in basal bone marrow medium (BBMM; IMDM with 30% FCS, 1% BSA [Sigma], 10−4 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, 10−6 mol/L hydrocortisone, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mmol/L l-glutamine) containing the following cytokines: 10 U/mL of rH Epo, 0.001 ng/mL rH GM-CSF, and 0.01 U/mL rH IL-3. CD34+ cells were plated on dishes coated either with irradiated normal human bone marrow stromal cell monolayers11 or with the CH-296 fragment of recombinant fibronectin (supplied by Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan), as recommended by the manufacturer's protocol. Half the culture media was replaced twice daily, 12 hours apart, with filtered viral supernatant from the L-tNGFR-SN PG13 cells for 3 days. On days 4 and 5, cells were harvested, labeled with the antibody to NGFR (MC192) as described above, and sorted on the FACS-Vantage flow cytometer.

RESULTS

In vitro model for production of RBCs from human CD34+progenitor cells.

CD34+ cells were isolated from the mononuclear cell fraction from cord blood, bone marrow, or peripheral blood to greater than 90% to 95% purity. The mononuclear fraction was subjected to RBC lysis before CD34 isolation to prevent any previously formed RBCs from contaminating the cultures. The purified human CD34+ cells were placed in erythroid differentiation conditions by using very high concentrations of Epo and low concentrations of GM-CSF and IL-3 in liquid culture, as detailed in the Materials and Methods. Differentiation was assessed by Wright Giemsa staining of portions of the cultured cells at serial time intervals to determine morphology.

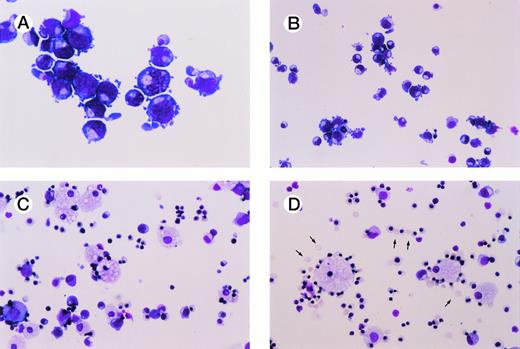

Figure 1 shows a representative experiment performed using bone marrow CD34+ cells cultured in erythroid differentiation conditions. Nearly all of the cells in culture consisted of erythroid cells that serially recapitulated in vivo erythropoiesis. Most of the cells in the culture consisted of pronormoblasts at day 7 (Fig 1A), basophilic normoblasts by 9 to 10 days (Fig 1B), and polychromatophilic normoblasts and orthochromatophilic normoblasts by day 12 of culture (Fig 1C). At day 12 to 14, greater than 90% to 95% of the cells in culture were erythroid cells and 5% to 10% of cells morphologically appeared to be promyelocytes and monocytes (Fig 1C). After 18 to 21 days of culture, erythroblastic islands formed, each consisting of a central macrophage surrounded by late orthochromatophilic normoblasts. This was soon followed by enucleation of 10% to 40% of the erythroid cells, with enucleation occurring around erythrocyte-macrophage associations (Fig1D).

In vitro erythropoiesis from normal human CD34+ progenitor cells. (A) through (D) show Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins at serial time intervals of cultures initiated with purified normal human bone marrow CD34+cells. Culture conditions used to induce erythroid differentiation are described in the Materials and Methods. Enucleated RBCs are marked with arrows. All photographs were taken at original magnification × 200. (A) Day 7; (B) day 9; (C) day 12; (D) day 19.

In vitro erythropoiesis from normal human CD34+ progenitor cells. (A) through (D) show Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins at serial time intervals of cultures initiated with purified normal human bone marrow CD34+cells. Culture conditions used to induce erythroid differentiation are described in the Materials and Methods. Enucleated RBCs are marked with arrows. All photographs were taken at original magnification × 200. (A) Day 7; (B) day 9; (C) day 12; (D) day 19.

At 3 weeks of culture, the enucleated RBCs were separated from the nucleated erythroid cells and macrophages by staining with a vital DNA dye, Hoechst 33342, followed by flow cytometry. Figure 2A shows a FACS analysis of a 3-week erythroid culture after staining with Hoechst 33342 and a monoclonal antibody to the erythroid membrane glycoprotein, glycophorin A. Glycophorin A was expressed on the majority of the cells, showing that nearly all of the cells in the culture were erythroid cells. Forty-two percent of the cells in this culture were not stained by Hoechst 33342 (Hoechst-negative). Microscopic examination of the sorted cells showed that Hoechst-negative cells were enucleated erythrocytes (Fig 2B). Conversely, the sorted Hoechst-positive cells were nucleated erythrocytes and macrophages in the culture (Fig 2C). Enucleated erythrocytes could similarly be generated from CD34+ cells isolated either from cord blood or peripheral blood. CD34+progenitor cells were also isolated from bone marrow or peripheral blood from SCA patients and differentiated to enucleated RBCs.

Isolation of enucleated erythrocytes from cultures by flow cytometry. (A) shows a FACS analysis of a 3-week-old culture initiated from CD34+ cells stained with Hoechst 33342 along the X-axis and glycophorin A along the Y-axis. The two distinct populations, Hoechst-negative [Hoechst (−)] and Hoechst-positive [Hoechst (+)] cells were sorted (marked with arrows). (B) and (C) depict the Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins of the Hoechst (−) and the Hoechst (+) populations, respectively.

Isolation of enucleated erythrocytes from cultures by flow cytometry. (A) shows a FACS analysis of a 3-week-old culture initiated from CD34+ cells stained with Hoechst 33342 along the X-axis and glycophorin A along the Y-axis. The two distinct populations, Hoechst-negative [Hoechst (−)] and Hoechst-positive [Hoechst (+)] cells were sorted (marked with arrows). (B) and (C) depict the Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins of the Hoechst (−) and the Hoechst (+) populations, respectively.

RBC characterization.

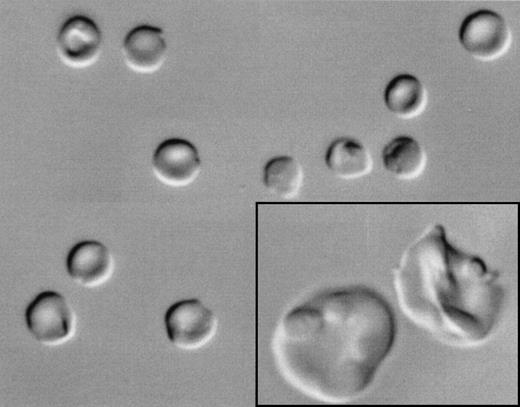

Morphologically, most of the Hoechst-negative cells appeared to be reticulocytes of varying stages of maturity with few mature RBCs. Differential interference contrast microscopy showed that these enucleated cells ranged from early polylobulated forms with a pinched or puckered membrane, resembling normal reticulocytes (enlarged in inset, Fig 3), to smooth biconcave discocytes (Fig 3). After staining with acridine orange, a nucleotide-binding fluorescent dye that emits red fluorescence when bound to RNA, most Hoechst-negative cells showed a fine reticulum of red fluorescence, which is consistent with the pattern seen in reticulocytes17 (data not shown). All Hoechst-negative cells showed surface expression of glycophorin A (Fig 2A), thus confirming their erythroid lineage, and the majority of the Hoechst-negative cells expressed transferrin receptor, consistent with the expression typically seen on reticulocytes18 (data not shown).

Differential interference microscopy of in vitro-generated enucleated erythrocytes from CD34+ cells from normal human bone marrow cells. CD34+ cells were cultured under erythroid differentiation conditions and enucleated cells were FACS sorted as described in the Materials and Methods. Morphologically, the erythrocytes ranged from early polylobulated forms with a pinched or puckered membrane, resembling normal reticulocytes (enlarged in inset), to smooth biconcave discocytes.

Differential interference microscopy of in vitro-generated enucleated erythrocytes from CD34+ cells from normal human bone marrow cells. CD34+ cells were cultured under erythroid differentiation conditions and enucleated cells were FACS sorted as described in the Materials and Methods. Morphologically, the erythrocytes ranged from early polylobulated forms with a pinched or puckered membrane, resembling normal reticulocytes (enlarged in inset), to smooth biconcave discocytes.

The mean cell volume (MCV) and volume distribution of the erythrocytes was measured using an aperture-impedance cell-sizing device (Coulter Counter). The MCV of the erythrocytes generated in vitro from normal CD34+ cells was 142.7 ± 17.68 μm3 (mean ± standard deviation, n = 4), which was larger than that of mature erythrocytes isolated from peripheral blood (which are typically 80 to 96 μm3)19 and more consistent with volumes of reticulocytes derived from peripheral blood (mean 131.6 ± 20.1, n = 5).

Globin chain analyses of in vitro derived erythrocytes.

Reverse-phase HPLC analyses were performed to determine the types of globin chains produced by the RBCs derived in vitro from bone marrow CD34+ cells (Fig 4). Hemolysates from the same number of normal umbilical cord blood RBCs and peripheral blood RBCs were also analyzed as controls for fetal and adult hemoglobin, respectively. Figure 4A and B depict the HPLC analysis of normal cord blood and peripheral blood, respectively. The major β-globin cluster chains expressed in cord blood were the fetalGγ and Aγ-globins with some adult β-globin (Fig 4A), as expected. The globin chain analysis of normal adult peripheral blood showed that the major β-cluster globin was β-globin (Fig 4B). Figure 4C shows an HPLC analysis of the cultured enucleated erythrocytes generated from CD34+ cells from normal bone marrow after 18 days of culture. Nearly all β-cluster globin chains produced are β-globin, with minimal amounts of γ-globin chains. Thus, the hemoglobin synthesis in the culture conditions described herein mimics the in vivo adult or postnatal pattern of globin production rather than the fetal pattern of γ-globin synthesis.

Globin chain synthesis by erythrocytes derived in vitro resembles adult pattern of globin synthesis. (A) and (B) show the reverse-phase HPLC analyses of normal umbilical cord blood and adult peripheral blood (representing fetal and adult-type globin production), respectively. (C) shows the same analysis on enucleated erythrocytes generated in vitro from CD34+ cells from normal bone marrow and sorted after Hoechst 33342 labeling. The order of appearance of various globin chains (from left to right) is as follows: β-, δ-, α-, AγT-, Gγ-, and AγI-globin. The X-axes represent retention time and the Y-axes represent absorbance.

Globin chain synthesis by erythrocytes derived in vitro resembles adult pattern of globin synthesis. (A) and (B) show the reverse-phase HPLC analyses of normal umbilical cord blood and adult peripheral blood (representing fetal and adult-type globin production), respectively. (C) shows the same analysis on enucleated erythrocytes generated in vitro from CD34+ cells from normal bone marrow and sorted after Hoechst 33342 labeling. The order of appearance of various globin chains (from left to right) is as follows: β-, δ-, α-, AγT-, Gγ-, and AγI-globin. The X-axes represent retention time and the Y-axes represent absorbance.

Transduction of CD34+ cells with a cell surface marker gene and expression of the gene product in the enucleated RBC progeny.

The potential for introducing genes into progenitor cells and attaining expression in the resultant erythrocyte progeny was tested as a model of gene therapy for RBC disorders. Normal human CD34+ cells were transduced with a retroviral vector, L-tNGFR-SN, carrying a cell surface reporter, the tNGFR, as a marker gene.14 Transduced cells expressing the reporter gene were identified by labeling cells with MC192, a monoclonal antibody to rat p75 NGFR. Figure 5A shows the tNGFR expression of the CD34+ cells transduced with the L-tNGFR-SN vector supernatant (solid histogram) 4 days after transduction. Expression of tNGFR was observed on 44.6% of the cells.

Transduction of CD34+ cells with a cell surface marker gene and expression of the gene product in the enucleated RBC progeny. (A) is an FACS analysis of CD34+cells at day 4 posttransduction with the retroviral vector L-tNGFR-SN (solid histogram) when labeled with the antibody against tNGFR, MC192 (shown on the X-axis). Sham-transduced cells (open histogram) were used to set gates for the flow cytometry of tNGFR-expressing [tNGFR(+)] cells and the nonexpressing [tNGFR(−)] cells. The tNGFR(−) and tNGFR(+) cells were subjected to erythroid differentiation and reanalyzed by three-color FACS analyses at day 18 of culture by labeling cells with biotinylated MC192 and streptavidin PE, FITC-conjugated anti-glycophorin A, and Hoechst 33342. Cultures derived from the tNGFR(−) (B and D) and the tNGFR(+) (C and E) populations are shown.

Transduction of CD34+ cells with a cell surface marker gene and expression of the gene product in the enucleated RBC progeny. (A) is an FACS analysis of CD34+cells at day 4 posttransduction with the retroviral vector L-tNGFR-SN (solid histogram) when labeled with the antibody against tNGFR, MC192 (shown on the X-axis). Sham-transduced cells (open histogram) were used to set gates for the flow cytometry of tNGFR-expressing [tNGFR(+)] cells and the nonexpressing [tNGFR(−)] cells. The tNGFR(−) and tNGFR(+) cells were subjected to erythroid differentiation and reanalyzed by three-color FACS analyses at day 18 of culture by labeling cells with biotinylated MC192 and streptavidin PE, FITC-conjugated anti-glycophorin A, and Hoechst 33342. Cultures derived from the tNGFR(−) (B and D) and the tNGFR(+) (C and E) populations are shown.

CD34+ cells expressing tNGFR on the surface [tNGFR(+)] and those not expressing the surface reporter [tNGFR(−)] were sorted by flow cytometry 4 days after transduction, and each population was cultured in erythroid differentiation conditions. After 3 weeks in culture, both the tNGFR(+) and tNGFR(−) cells were subjected to a three-color FACS analysis using Hoechst 33342, antihuman glycophorin A antibody (FITC-labeled), and antirat tNGFR antibody, MC192 (PE-labeled). Figure 5B and C demonstrate that the majority of cells in both the tNGFR(−) and tNGFR(+) populations were erythroid cells, based on surface expression of glycophorin A. Most cells that had been sorted as tNGFR(−) at day 4 did not express tNGFR on their surface at day 18 of culture (Fig 5B), whereas those that had been sorted as tNGFR(+) at day 4 still expressed tNGFR on their surface at day 18 of erythroid culture (Fig 5C). Furthermore, whereas tNGFR expression was absent on the surface of erythrocytes derived from the untransduced cell population [tNGFR(−), fig 5D], tNGFR was expressed on the surface of 89% of the enucleated RBCs in the transduced cell population [tNGFR(+), Fig 5E]. Expression of the tNGFR transgene in the enucleated erythrocytes was detected both by flow cytometry (Fig 5E) and by immunohistochemistry (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The goals of the present study were to (1) develop a model of in vitro erythropoiesis from human CD34+ progenitor cells and (2) to test the potential for insertion of an exogenous gene into CD34+ progenitor cells and attainment of expression of the gene in the enucleated RBC progeny.

Production and isolation of a pure population of terminally differentiated, enucleated RBCs from human CD34+ cells, in sufficient numbers for biophysical studies and for the study of gene transfer and expression, is a unique feature of the current model that has not been previously described.

The most commonly used in vitro assays from CD34+ primitive progenitor cells result in production of erythroid colonies, composed of early (BFU-E) or late (CFU-E) erythroid progenitors in methylcellulose or plasma clots.6,7,20-22 However, the hemoglobinized colonies in semisolid media do not result in terminally differentiated enucleated erythrocytes. Most liquid long-term cultures are limited by the presence of heterogenous mixtures of mainly myeloid cells with arrest of erythropoiesis at the CFU-E level.23,24 Very high levels of Epo have been reported to suppress the number of myeloid cells in culture.25 26

Highly purified erythroid colony-forming cells (ECFCs) have been generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB-MNC) using a two-phase culture system.27 Here, PB-MNC that were depleted of platelets, T cells, and myeloid cells27-29 were cultured in semisolid medium containing IL-3 and Epo for 1 week (phase 1). Thereafter, the nonadherent cells (enriched in ECFC) were harvested from the semisolid cultures and placed in liquid culture containing Epo to obtain large numbers of CFU-E (phase 2).27 The two-phase culture system was also adapted to generate terminally differentiated cells from PB-MNC.8,30,31 PB-MNC were initially grown in semisolid medium containing either 5637-bladder carcinoma cell-conditioned medium8,30,31 or phytohemagglutinin-stimulated leukocyte conditioned medium9(phase 1). The conditioned media provided erythroid burst-promoting activity (BPA).24 After 1 week, cells in the semisolid cultures (enriched in erythroid precursors) were harvested and terminally differentiated under low oxygen concentrations (5% O2) in liquid culture containing Epo (phase 2).8,9,30 31

Dexter et al24 had reported terminal erythroid differentiation in murine long-term bone marrow cultures when anemic mouse serum was added to the cultures as a source of BPA.

Availability of recombinant cytokines made possible the identification of BPA effects of a number of cytokines, viz, IL-3, stem cell factor (SCF), and GM-CSF, etc.32-36 Chelucci et al37 reported unilineage differentiation of purified primitive hematopoietic progenitors if high concentrations of Epo along with low concentrations of GM-CSF and IL-3 were used. However, they have followed their cultures up to 12 to 14 days and have not reported terminal RBC differentiation and development of enucleated RBCs. In the current model, we have used very high concentrations of Epo and low levels of GM-CSF and IL-337 to culture CD34+cells, derived either from bone marrow, cord blood, or peripheral blood, to generate terminally differentiated RBCs. We have further isolated the enucleated RBCs from the rest of the erythroid culture by flow cytometry, based on the use of a DNA-binding dye to isolate cells that have undergone enucleation.

The RBCs generated in vitro showed different stages of normal erythrocyte maturation from reticulocytes to mature discocytes. They had higher mean corpuscular volumes than erythrocytes isolated from peripheral blood, because the majority of these cells resembled reticulocytes in morphology, RNA staining, and transferrin receptor expression. We have also generated RBCs from bone marrow- and peripheral blood-derived CD34+ cells from individuals with SCA.

An important feature of the RBCs generated in vitro in the current model was production of adult β-globin (Hb A), with negligible fetal globin (Hb F) synthesis, mimicking in vivo erythropoiesis. Similarly, Hb S was produced in RBCs derived from CD34+ cells from patients with SCA. Because problems in hemoglobinopathies such as SCA and thalassemia become manifest with adult globin production,1,38 a model with adult-type erythropoiesis is essential to study the pathophysiology of hemoglobinopathies and test effective therapeutic strategies. Significant Hb F production has been observed in erythroid bursts grown from CD34+ cells cultured in semisolid media in vitro, and the amount of Hb F has been shown to be proportional to the concentrations of cytokines.1,33,39-43 It has also been observed that the proportion of Hb F in erythroid colonies is inversely proportional to maturation of the colonies.1 44 The low levels of Hb F observed in the RBCs generated in vitro in our system could be ascribed to the very low concentrations of IL-3 and GM-CSF in the culture conditions, as well to terminal erythroid differentiation.

To examine the potential application of this model to studies of gene therapy of RBC disorders, we have inserted a cell surface reporter gene into CD34+ progenitor cells and show expression of the gene product on the surface of the enucleated RBC progeny. We have also generated green fluorescent RBCs after transduction of CD34+ cells with a vector encoding the jelly fish green fluorescent protein, MND-eGFP-SN45 (data not shown). Detection of an exogenously inserted gene product in the enucleated human RBCs after transduction of CD34+ progenitor cells has not been previously described. The in vitro model of human erythropoiesis can therefore be used to genetically manipulate hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells from patients with congenital RBC defects and test the functional effects of the gene therapy in the target RBC progeny.

We are currently using this model to study RBC abnormalities in sickle cell disease and the possibility of reversing these abnormalities by gene therapy. Efficient ex vivo RBC production could also have implications for production of RBCs for transfusions, if sufficient quantities can be generated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Debbie Gribbons, Clinical Nurse Specialist, and the nursing staff in the Hematology-Oncology day hospital, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, for collecting the phlebotomized blood from patients with sickle cell anemia; the nursing staff of the Labor and Delivery and Birthing Center, Kaiser Permanente, Los Angeles for collecting the cord blood samples; and Takara Shuzo, Inc (Otsu, Japan) for providing us with the CH-296 fragment of fibronectin.

Supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant No. 5P60-HL48484-02, by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant No. 5R01-AI23547-10, by the Specialized Center of Research (SCOR) in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Biology HL9410B, and the J. Connell Gene Therapy Program.

Address reprint requests to Punam Malik, MD, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, Mail stop # 62, 4650 Sunset Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90027; e-mail: malik@hsc.usc.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

![Fig. 2. Isolation of enucleated erythrocytes from cultures by flow cytometry. (A) shows a FACS analysis of a 3-week-old culture initiated from CD34+ cells stained with Hoechst 33342 along the X-axis and glycophorin A along the Y-axis. The two distinct populations, Hoechst-negative [Hoechst (−)] and Hoechst-positive [Hoechst (+)] cells were sorted (marked with arrows). (B) and (C) depict the Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins of the Hoechst (−) and the Hoechst (+) populations, respectively.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/8/10.1182_blood.v91.8.2664.2664_2664_2671/5/m_blod408mal02z.jpeg?Expires=1769082450&Signature=s4jFG0--L3aoPuIe74FV4ic6Rpg6OYsjWNeZm4FmyvpKCcYYqJgssO7bpVAw7bFlAJSBwZbJouho2kyu6a73yW9C2cJ14etaYLsIE7Y3BuYECxn5Srldog8w~Zi5J4YjQhixolPEX9mnhWbLVPaeX1pSDVmFqfspAJuw0aAxWHzY-l7jH2BJMhSLWhEB7Z5LSa45LF7xIdzbDoJvGNzm0O3LfSRnlEoWHu8XU8ppGbWkzvD5O7OAyUCBSq4ZdMt2SPzxD5mDgmlqzmYaolyunZcSmU~JSOzogVWKj7nicihLCyLjtBJ3kidtIWA9n4vhpISg27R0Rg4PDLlEyvTRAA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. Transduction of CD34+ cells with a cell surface marker gene and expression of the gene product in the enucleated RBC progeny. (A) is an FACS analysis of CD34+cells at day 4 posttransduction with the retroviral vector L-tNGFR-SN (solid histogram) when labeled with the antibody against tNGFR, MC192 (shown on the X-axis). Sham-transduced cells (open histogram) were used to set gates for the flow cytometry of tNGFR-expressing [tNGFR(+)] cells and the nonexpressing [tNGFR(−)] cells. The tNGFR(−) and tNGFR(+) cells were subjected to erythroid differentiation and reanalyzed by three-color FACS analyses at day 18 of culture by labeling cells with biotinylated MC192 and streptavidin PE, FITC-conjugated anti-glycophorin A, and Hoechst 33342. Cultures derived from the tNGFR(−) (B and D) and the tNGFR(+) (C and E) populations are shown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/8/10.1182_blood.v91.8.2664.2664_2664_2671/5/m_blod40851005ay.jpeg?Expires=1769082450&Signature=40~Z~KZWnrSID8yLrhIzScSJcHTzYvo8G2wKoz-TCF12sPJ6U5Ag8Sa0GDGG84~spQAYgHM7kBjrrCHb0C2IhAAhrMttXj-r-OEoNwlHhbrbjO6ghXcrPBV~ONrOyeTuN1J0Z2GEzXtqxHsB8ZfqppMZipJIcOkU6sYiNhP4dXCfwmBGWky5bcSdIvhgVj1lOBjgN1yTEI~qTbA8w8VpsiRdL4uk19zBNWRKOcZnj2m28CORrbJ5UWNu7jhhaB5D4FrwNF00cjM1t9n9LN01INjW~A8BRYdkvXqBpspGa-WrHoDlSkV5c5lRaBE288pt3cCSne0O4hfcI~xFkdfEjA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. Transduction of CD34+ cells with a cell surface marker gene and expression of the gene product in the enucleated RBC progeny. (A) is an FACS analysis of CD34+cells at day 4 posttransduction with the retroviral vector L-tNGFR-SN (solid histogram) when labeled with the antibody against tNGFR, MC192 (shown on the X-axis). Sham-transduced cells (open histogram) were used to set gates for the flow cytometry of tNGFR-expressing [tNGFR(+)] cells and the nonexpressing [tNGFR(−)] cells. The tNGFR(−) and tNGFR(+) cells were subjected to erythroid differentiation and reanalyzed by three-color FACS analyses at day 18 of culture by labeling cells with biotinylated MC192 and streptavidin PE, FITC-conjugated anti-glycophorin A, and Hoechst 33342. Cultures derived from the tNGFR(−) (B and D) and the tNGFR(+) (C and E) populations are shown.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/8/10.1182_blood.v91.8.2664.2664_2664_2671/5/m_blod40851005by.jpeg?Expires=1769082450&Signature=BlyURHabrlYcvKMLt0yTwMpQBuUutcOqseqzCrzbhErwsCKgy5VdXdA3cTVskNSwYG8QP4bQXo5IrPH0wAhiMiIPXEvDZn4HEnaBOn7MazxW82oxMDE-NccwS7l-3nTzj3Ku7Mlf9nVyCWZ-vXrWKf9taavX2I~-xivIY71~x8PfDAtIQiSwPvwc1n~5tLL-WB80WUhy5tE-r-sFnk2MkS2mOGutCbpRVTcGg3a0Za1G98Vk2V~idqhbexPmDjBeAQuxFhEbHSL1QYLuwsGrqfWpF1UkJhdh4nDIA3jzb7lQRryDf0m~eEXiF2CB-zLnfirVRYgiSKVDQ7xuQi9TDQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal