Abstract

Human natural killer (NK) cells were thought to express only FcγRIIIA (CD16), but recent reports have indicated that NK cells also express a second type of FcγR, ie, FcγRII (CD32). We have isolated, cloned, and sequenced full-length cDNAs of FcγRII from NK cells derived from several normal individuals that may represent four different products of the FcγRIIC gene. One transcript (IIc1) is identical with the already described FcγRIIc form. The other three (IIc2-IIc4) appear to represent unique, alternatively spliced products of the same gene, and include a possible soluble form. Analyses of the full-length clones have revealed an allelic polymorphism in the first extracellular exon, resulting in either a functional open reading frame isoform or a null allele. Stable transfection experiments enabled us to determine a unique binding pattern of anti-CD32 monoclonal antibodies to FcγRIIc. Further analyses of NK-cell preparations revealed heterogeneity in CD32 expression, ranging from donors lacking CD32 expression to donors expressing high levels of CD32 that were capable of triggering cytotoxicity. Differences in expression were correlated with the presence or absence of null alleles. These data show that certain individuals express high levels of functional FcγRIIc isoforms on their NK cells.

HUMAN NATURAL killer (NK) cells represent a subset of lymphocytes distinct from B cells and T cells, which are capable of mediating spontaneous cytotoxicity against certain target cells without requiring the recognition of antigen in the context of the MHC.1,2 However, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) determinants have been shown to influence cytolytic function.3,4 NK cells also kill immunoglobulin-coated targets through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).5-7 Following activation, NK cells secrete cytokines and growth factors that regulate the physiology and function of other cells of the immune system.8,9 Although the receptors involved in direct recognition and killing of target cells are only now being defined, a receptor that is responsible for triggering NK-cell–mediated ADCC, namely FcγRIIIA (CD16), has been extensively studied.7,10 CD16 is a receptor for the Fc portion of IgG and is capable of binding complexed or aggregated IgG and also IgG in monomeric form (mIgG).11-13

Until recently, it was believed that CD16 was the only FcγR to be expressed by human NK cells. We, as well as others,14,15have shown that FcγRII (CD32) is also expressed by some human NK cells. FcγRII is a glycoprotein of approximately 40 kD that binds IgG with low affinity. It is one of the most widely distributed FcγRs, being expressed on cells of both myeloid and lymphoid lineages, as well as on cells of nonhematopoietic origin.16-18 Three genes have been described for FcγRII (FcγRIIA, B, and C) that encode a total of six transcripts (FcγRIIa1, a2, b1, b2, b3, and c) representing alternatively spliced forms of the three genes.19,20 Each protein consists of two IgG-like extracellular domains, encoded in two exons (EC1 and EC2), a transmembrane region encoded by a separate exon (TM), and an intracytoplasmic tail encoded by three separate exons (C1, C2, and C3).19,20 A further polymorphism for FcγRIIA has been described, with two codominantly expressed alleles, namely R131 high responder (HR) and H131 low responder (LR), which differ substantially in their ability to bind human IgG2 and murine IgG1.21 22

All of the known FcγRII isoforms are highly homologous in the extracytoplasmic domains, but ligand binding specificity differences have been reported.16-18 The intracytoplasmic domains are less homologous, and triggering through different isoforms results in distinct functions.23,24 It has been recently reported that cross-linking of FcγRIIa results in upregulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, phagocytosis of opsonized particles, as well as internalization of immune complexes.25-27 FcγRII is known to associate with the γ-chain of FcεRI, and this results in enhanced activation of these functions.28,29 In contrast, triggering through the FcγRIIb isoforms results in downmodulation of a previous state of cell activation triggered via antigen receptors on B cells (BCR), T cells (TCR), or via another FcR.30 31

The FcγRIIC gene represents an unequal cross-over event between genes IIA and IIB, as EC1, EC2, TM, and C1 exons are derived from the FcγRIIB gene, whereas C2 and C3 exons derive from the FcγRIIA gene.32 This generates a hybrid gene product that has been found to be expressed mainly by monocytes/macrophages and polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells.33 Its functional characteristics have not been studied, but it is thought that its binding specificities will be similar to the FcγRIIb isoforms but will use similar signaling pathways as FcγRIIa.17

Preliminary results reported by our group14 indicated that human NK cells express FcγRII at levels that vary among donors. Flow cytometric studies, performed with IV.3 and 41H16 (two anti-CD32 monoclonal antibodies [MoAbs] that bind different epitopes), revealed different patterns of staining ranging from no expression at all to low expression detected using both IV.3 or 41H16 MoAbs. Some other individuals exhibited significant levels of CD32 expression on their NK cells (60% to 90%) when using the 41H16 MoAb, even though the level of IV.3 binding in the same donor was low (6% to 12%). Mantzioris et al15 showed in a different study that approximately 88% of CD3−/CD16+/CD56+ cells (which represent the NK population) were positive for 41H16 staining. In addition, we found that the CD32 on NK cells was an activating molecule because Ca2+ flux and reverse ADCC (rADCC) were triggered following anti-CD32 MoAb stimulation of NK cells.14

In this study, we report that human NK cells express four different transcripts of the FcγRIIC gene. One of the products, designated FcγRIIc1, is the same as the previously described IIc isoform; the other three transcripts, designated IIc2-c4, represent previously undescribed, alternatively spliced products of the IIC gene and possibly include a soluble form. In addition, we describe an allelic polymorphism in the EC1 domain, which in some individuals results in two null FcγRIIc alleles that may determine lack of FcγRIIc expression. Expression of FcγRIIc in individuals with the open reading frame (ORF) allele was shown by flow cytometric and biochemical means on purified NK cells. For the donors expressing FcγRIIc on their NK cells, we describe a unique anti-CD32 MoAb binding pattern that, together with the allelic polymorphism, provides an explanation for the previously observed lack of CD32 expression by some NK-cell preparations. We also show that CD32 on NK cells is a functional molecule, capable of triggering cytotoxic events.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MoAbs.

Anti-CD16 and -CD32 MoAbs used were: 3G8 and IV.3 (Medarex, Annandale, NJ); 41H16 (ascites), a gift from Dr M. Longenecker (University of Alberta, Canada) and purified at the UPCI hybridoma facility; KB61, a gift from Dr K. Pulford (University of Oxford, UK); and AT10 (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA). F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse IgG (GAMIgG)-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was purchased from Tago Inc (Burlingame, CA). MoAbs used for phenotyping the NK cells were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ) and consisted of anti-CD56 (Leu 19)-phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD19 (Leu12)-PE, anti-CD14 (Leu 3M)-FITC, anti-CD3 (Leu 4)-FITC.

Human cell lines.

U937 (monocyte cell line), K562 (erythroleukemia), RPMI 8866 (Epstein-Barr virus–transformed B-cell line), Jurkat (T-cell leukemia), and Molt 4 (T-cell lymphoma) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithesburgh, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; GIBCO-BRL), 2 mmol/L glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μmol/L streptomycin, subsequently referred to as complete culture medium (CCM).

NK cell purification and NK cell analysis from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).

Heparinized whole blood or leukocytes from leukapheresed blood from normal donors was centrifuged on a Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) gradient, and PBMC were obtained as previously described.34 PBMC were (1) either directly analyzed by flow cytometry in two color staining, using PE-conjugated anti-CD56 to define the NK population, and indirect staining with anti-CD32 or anti-CD16 MoAbs followed by FITC-GAMIgG or (2) incubated with a cocktail of anti-CD3, anti-CD19, anti-CD14, and anti-CD64 MoAbs, at 4°C for 30 minutes and exposed first to GAMIgG-covered magnetic beads (PerSeptive Bio Systems, Farmingham, MA), and for a second round to GAMIgG-covered Dynabeads M450 (Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway). Using a magnet (Bio-Mag Separator; Advanced Magnetics, Cambridge, MA), highly purified resting NK cells (≥95% CD3−CD56+ CD16+ cells) were obtained by negative selection. Fourteen-day interleukin-2 (IL-2)– activated human NK cells, referred to as A-NK cells, (generously provided by Dr N. Vujanovic, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute) were generally 100% CD3−/ CD56+/CD16+cells.35 The purity of all NK-cell preparations as well as the detection of CD32 expression on these cells was performed by direct and indirect flow cytometric analyses as previously reported.36

RNA isolation and reverse transcription (RT).

Total cellular RNA was isolated from all cell types using the RNAzol B (Biotex Labs Inc, Houston, TX) method. cDNAs were synthesized by RT from 2 μg of total RNA isolated from each cell source using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Pharmacia-Biotech). A human NK cell cDNA library constructed in λgt10 phage was a generous gift from Dr S. Ziegler (Darwin Molecular, Inc, Bothell, WA).37FcγRIIa1, FcγRIIb1, and FcγRIIb2 cDNA clones were a kind gift from Dr J. Ravetch (Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York, NY).

PCR, Southern Blotting (SB), and Dot Blotting (DB).

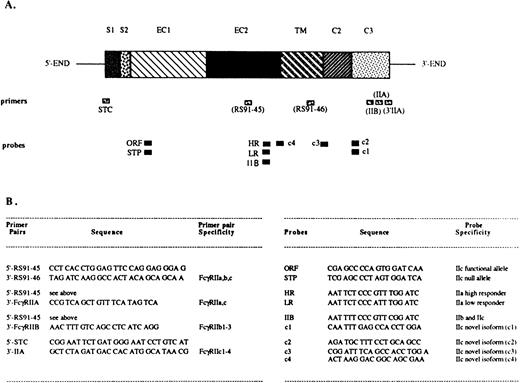

The PCR reactions were performed using sets of primers specific for different FcγRII isoforms (Fig 1).EcoRI/Xba I restriction sites were designed into the primers to facilitate cloning. The PCR amplification conditions consisted of a denaturing step at 94°C for 1 minute, annealing at 55°C for 2 minutes, and extension at 72°C for 3 minutes, for a total of 30 cycles. When the human NK cell λgt10 library was used as a template, an additional 15-minute denaturation step was introduced before the usual PCR conditions. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in an ethidium bromide–containing 2% agarose gel, transferred onto Nytran membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH), and hybridized with digoxygenin-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN)–labeled oligonucleotides.38 In certain instances, the PCR products were dot blotted onto the Nytran membranes as previously described39 and further hybridized. The probes were designed to specifically hybridize to the known FcγRII isoforms or to the novel FcγRIIc isoforms (Fig 1). All oligonucleotide primers and probes were synthesized at the University of Pittsburgh, Department of Molecular Genetics and Biochemistry (MGB) core facility, and were purified using NAP-10 columns containing Sephadex G-25 Medium of DNA Grade (Pharmacia Biotech).

Localization and sequence of FcγRII-specific primers and probes. The structure of an FcγRII cDNA is shown in (A), with the exons depicted as boxes, and with their names above: S1, first signal exon; S2, second signal exon; EC1, first extracellular exon; EC2, second extracellular exon; TM, transmembrane exon; C2, second intracytoplasmic exon; C3, third intracytoplasmic exon. Primer and probe locations are indicated below the cDNA map. (B) Indicates the primer pairs and probe names, specificities, and sequences.

Localization and sequence of FcγRII-specific primers and probes. The structure of an FcγRII cDNA is shown in (A), with the exons depicted as boxes, and with their names above: S1, first signal exon; S2, second signal exon; EC1, first extracellular exon; EC2, second extracellular exon; TM, transmembrane exon; C2, second intracytoplasmic exon; C3, third intracytoplasmic exon. Primer and probe locations are indicated below the cDNA map. (B) Indicates the primer pairs and probe names, specificities, and sequences.

Cloning and DNA sequence analysis.

The full-length FcγRIIc cDNAs, obtained from RT-PCR amplifications, were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, purified, and concentrated using a QIAquick PCR purification column (Qiagen Inc, Chatsworth, CA). They were then cloned into theEcoRI/Xba I (GIBCO-BRL) digested pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen Corp, San Diego, CA). The nucleotide sequence of cloned cDNAs was determined by ABI Prism fluorescent dye dideoxy-terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) at the University of Pittsburgh MGB core facility.

Stable transfection of Jurkat cells.

Full-length FcγRIIc1, IIc3 as well as FcγRIIb1 cDNAs were inserted into the pCDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen Corp). These constructs were transfected by electroporation into Jurkat cells as previously described.40 Briefly, aliquots of 1 × 107 Jurkat cells were transformed with 20 μg plasmid cDNA using an electroporation apparatus (BXT, San Diego, CA) set at 200 V and 1690 μF. Forty-eight hours later, stable transfectants were selected with the neomycin analog G418 (GIBCO-BRL) at 500 μg/mL. After 3 weeks the FcγRII expressing cells were purified by panning.41 Briefly, the cells were incubated with an anti-CD32 MoAb (KB61) for 30 minutes on ice, washed three times, and the positive cells were then selected by incubating them in plates precoated with GAMIgG. The transfected cells were stable for CD32 high expression throughout the studies performed.

Flow cytometric analyses of CD32 expression in stable transfectants.

Indirect flow cytometric analyses were performed using four different anti-FcγRII MoAbs and FITC-labeled F(ab′)2 fragment of GAMIgG staining as previously described.36 Data acquisition was performed on a FACStar Plus Cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Cell labeling, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting.

U937 cells as well as PBLs or highly purified NK cells isolated from donor 2 were biotinylated as described elsewhere.42Briefly, 2 × 107 cells were incubated in 0.1 mg/mL sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) for 30 minutes at 4°C, washed five times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lysed in 1% Triton X-100 lysing buffer containing 10 mmol/L EDTA, 2 mmol/L phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/mL antipain, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 10 μg/mL pepstatin A, for 30 minutes at 4°C. Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes to remove cell debris and nuclei. F(ab′)2 fragments of GAMIgG coupled to CnBr-activated Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia LKB) were incubated with 41H16 MoAb or mIgG2a for 3 hours at 4°C as described.43Immunoadsorbtion of cell lysates onto antibody-coupled beads was performed overnight at 4°C; the immunoprecipitates were washed with lysis buffer and electrophoresed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels (under nonreducing conditions). The separated proteins were transferred to PVDP membranes (Immunobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA), blocked with a 3% nonfat dry milk and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) PBS solution for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated neutravidin (Pierce) for 1 hour at room temperature. The blots were washed in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20, and the protein bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Cytotoxicity assay.

Cytotoxicity was measured by reverse antibody-dependent cytotoxicity (rADCC) using the 4-hour 51Cr-release microcytotoxicity assay, as previously described in detail.44 The FcR+ target used in the assay was P815 (rat mastocytoma). The spontaneous release was always less than 10%. Results were expressed in percentage of specific cytotoxicity calculated according to the formula

RESULTS

NK cells express FcγRIIa/IIc transcripts but not FcγRIIb.

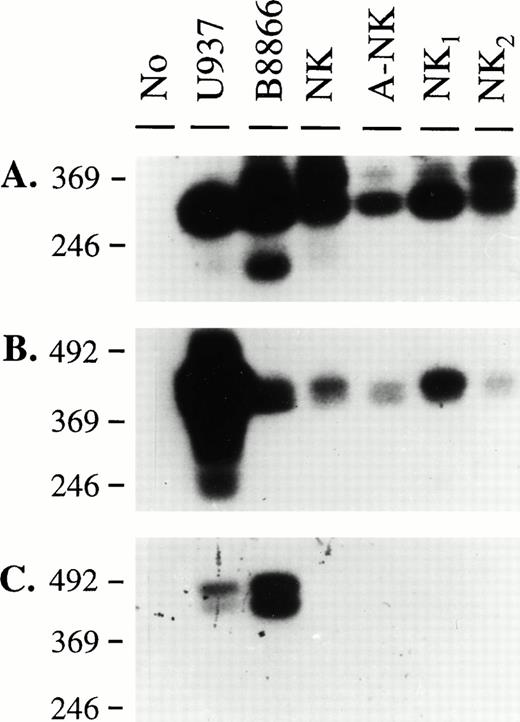

Our previous findings showed that some human NK cells express CD32, and that this molecule has triggering abilities.14 We, therefore, designed RT-PCR experiments to molecularly characterize the type of FcγRII transcript(s) present in NK cells. We isolated RNA from highly purified NK-cell preparations as well as from cell lines known to be positive for FcγRII. Sets of primers that would amplify all known CD32 isoforms (RS91-45 and RS91-46), or specifically the FcγRIIa/IIc (RS91-45 and IIA) or the FcγRIIb isoforms (RS91-45 and IIB), were designed (Fig 1). The specificity of the primers and probes used in these studies was confirmed using cDNA clones of FcγRIIa1, FcγRIIb1, and FcγRIIb2 (data not shown). These primers were used to generate PCR products from the cells described above, and in addition, SB analyses were performed using a probe (RS91-46) that would hybridize with all FcγRII cDNAs, to confirm the identity of these amplified products. As shown in Fig 2, the U937 cell line and a B-cell line expressed message for both FcγRIIa/c and IIb isoforms, confirming previous reports regarding the coexpression of these isoforms by these cell lines.16 27 In the four NK-cell preparations, only FcγRIIa/IIc-specific products could be amplified (Fig 2B), and no bands were visible when the FcγRIIb-specific primers were used (Fig 2C). Therefore, these results suggested that NK cells expressed either the FcγRIIa and/or the FcγRIIc isoforms.

Southern blot analysis of RT-PCR amplification products using FcγRII-specific primers. RNA isolated from the indicated cell sources was used to obtain cDNAs by reverse transcription. PCR amplification was performed using sets of primers specific for all FcγRII isoforms (A), Fcγ RIIa, c isoforms (B), and FcγRIIb isoforms (C). A 2% agarose gel was run and Southern blotting was performed as described in Materials and Methods with RS91-46 as the hybridizing probe. Specific bands of expected size for each primer pair were detected in each panel (334 bp for RS9145-RS9146 primer pair, 442 bp for RS9145-FcγIIA primer pair, and 441 bp/384 bp for RS9145-FcγIIB primer pair).

Southern blot analysis of RT-PCR amplification products using FcγRII-specific primers. RNA isolated from the indicated cell sources was used to obtain cDNAs by reverse transcription. PCR amplification was performed using sets of primers specific for all FcγRII isoforms (A), Fcγ RIIa, c isoforms (B), and FcγRIIb isoforms (C). A 2% agarose gel was run and Southern blotting was performed as described in Materials and Methods with RS91-46 as the hybridizing probe. Specific bands of expected size for each primer pair were detected in each panel (334 bp for RS9145-RS9146 primer pair, 442 bp for RS9145-FcγIIA primer pair, and 441 bp/384 bp for RS9145-FcγIIB primer pair).

NK cells express message for a hybrid form of FcγRII, namely FcγRIIc.

To determine which isoform of FcγRII was expressed in human NK cells, three oligonucleotide probes were designed that would discriminate among the IIa-HR (HR) and IIa-LR (LR) and IIc (IIB) transcripts (Fig1). Using the RS91-45 and IIA primer set, RT-PCR was performed on RNA isolated from three IL-2–activated NK-cell preparations (A-NK1-3), K562 and U937 cell lines (positive controls), and from Molt 4 (negative control). SB analyses on these PCR products were performed, and the results presented in Fig 3 show that all of the cells used for this PCR amplification, with the exception of Molt 4, expressed message for FcγRIIa and/or IIc (Fig 3A). The HR probe hybridized to both K562 and U937 PCR products, but not to the NK-cell–amplified products (Fig 3B); the LR probe hybridized only to the K562 amplification product, confirming that this cell line is heterozygous for both FcγRIIa HR and LR alleles (Fig3C).33 Furthermore, the IIB-probe hybridized to all PCR products amplified from the NK-cell preparations, as well as from U937 and K562 cells (Fig 3D). These findings indicate that the transcripts expressed by human NK cells represent a hybrid form, similar to the IIb isoform sequence at the 5′-end and to the IIa isoform sequence at the 3′-end. This type of transcript has been described as the product of the FcγRIIC gene,20 shown to be the result of an unequal crossover event between the IIA and IIB genes.32 Our results confirm previous reports that have shown that U937 and K562 cells also express the FcγRIIc isoform.33 The lack of amplification of transcripts for the FcγRIIA or FcγRIIB genes provides additional evidence that the NK preparations were highly pure because transcripts from either of these genes would readily appear from contaminating monocytes or B cells.

Southern blot analysis to determine the FcγRII isoforms expressed by human NK cells. RT-PCR with the FcγRIIa/c-specific primer pair on three A-NK cell samples, U937 and K562 cell lines (positive control), or Molt4 (negative control) was performed as described. The Southern blots were probed with oligonucleotides specific for all the FcγRII isoforms (RS91-46; [A]), for FcγRIIa (HR; [B] and LR; [C]) and for FcγRIIc (IIB; [D]), and cell-specific transcripts of the expected sizes were detected with each probe.

Southern blot analysis to determine the FcγRII isoforms expressed by human NK cells. RT-PCR with the FcγRIIa/c-specific primer pair on three A-NK cell samples, U937 and K562 cell lines (positive control), or Molt4 (negative control) was performed as described. The Southern blots were probed with oligonucleotides specific for all the FcγRII isoforms (RS91-46; [A]), for FcγRIIa (HR; [B] and LR; [C]) and for FcγRIIc (IIB; [D]), and cell-specific transcripts of the expected sizes were detected with each probe.

Human NK cells express four distinct types of FcγRIIc transcripts.

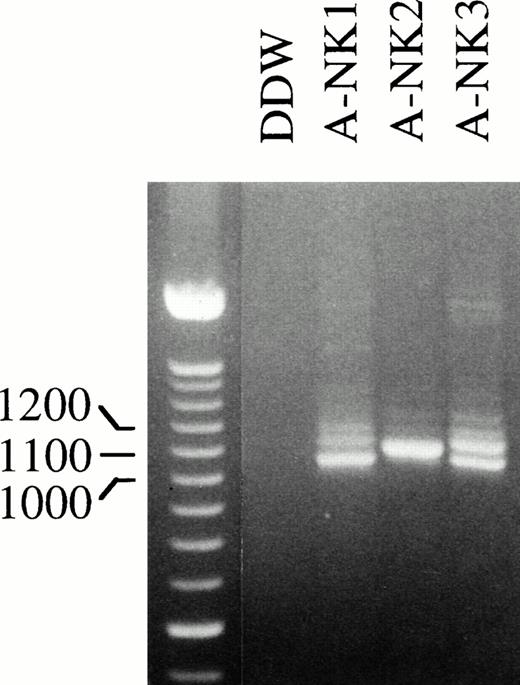

To confirm that human NK cells express FcγRIIc-specific transcripts, we next designed primers to amplify and clone full-length FcγRIIc-specific PCR products. RNA isolated from A-NK cells from 3 donors was used in RT-PCR reactions with STC and 3′IIA primers (Fig4); in addition, a human cDNA library, generated from a highly purified resting NK-cell population, was used as a template with the same set of primers to generate full-length FcγRIIc products (data not shown). The RT-PCR reactions were set up using the same amount of RNA from each cell source, and the resulting amplification products are shown in Fig 4. Interestingly, there was substantial donor heterogeneity in the number and abundance of bands amplified from each RT-PCR sample. A-NK2 showed a single band whereas two or three bands were amplified from the other two NK-cell donors. These PCR products were cloned, and 42 positive colonies were selected by colony hybridization using the RS91-46 probe. The purified cDNAs from all the positive clones were analyzed by gel electrophoresis, and four different sizes of inserts were detected (data not shown). Several representatives of each of these clones were sequenced.

Full-length FcγRIIc-specific RT-PCR analysis of NK cell RNA. RNA isolated from the indicated human A-NK cell preparations was reverse transcribed and PCR amplified with an FcγRIIc-specific primer pair that would generate full-length products and further analyzed on an EtBr containing 2% agarose gel. The 100-bp DNA ladder was used as a size marker.

Full-length FcγRIIc-specific RT-PCR analysis of NK cell RNA. RNA isolated from the indicated human A-NK cell preparations was reverse transcribed and PCR amplified with an FcγRIIc-specific primer pair that would generate full-length products and further analyzed on an EtBr containing 2% agarose gel. The 100-bp DNA ladder was used as a size marker.

FcγRIIc1 and three novel FcγRIIc isoforms are expressed in human NK cells.

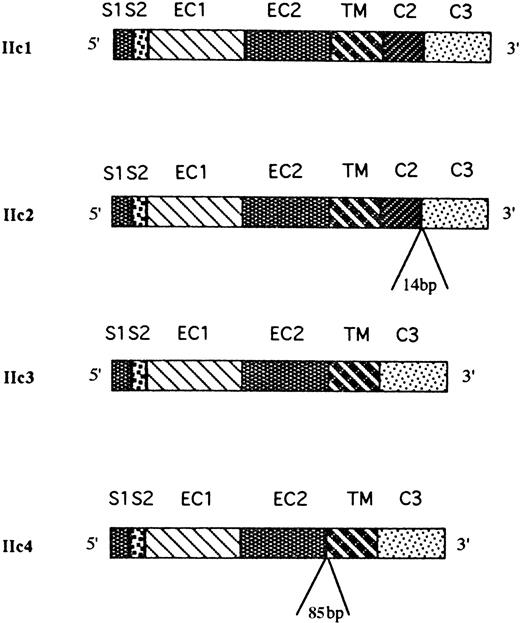

From the sequence data, four distinct FcγRIIc isoforms were identified that were homologous with the FcγRIIC gene, and a schematic map of the coding sequences of the four isoforms is presented in Fig 5. One of the cDNAs, designated FcγRIIc1, corresponded to the previously described FcγRIIc isoform. The other three cDNAs are likely to represent previously undescribed, alternatively spliced products of the same gene and have several insertions and deletions. A second cDNA (FcγRIIc2) had an insertion of 14 bp at the junction between the C2 and C3 intracytoplasmic exons that alters the reading frame of the encoded cytoplasmic tail resulting in a shortened cytoplasmic tail of 22 amino acids (aa) in length. The source of the 14-bp insertion was found at the intron/exon borders of the FcγRIIC gene with 3 nucleotides coming from the 5′-end of intron 6 and 11 nucleotides from the 3′-end of intron 6. The most frequent type of clone sequenced (FcγRIIc3) lacked the second intracytoplasmic exon (C2), and this resulted in a truncated 13 aa cytoplasmic tail (Fig6). Finally, sequence analyses of the fourth cDNA clone, designated FcγRIIc4, revealed a deletion of both C1 and C2 exons (similar to the IIc3 isoform) but, in addition, an insertion of 85 bp between the EC2 and TM exons was found that would appear to be an alternatively used exon. This insertion encodes 19 aa followed by a stop codon, which would result in a receptor lacking the TM region and which may represent a soluble form of FcγRIIc. Interestingly, the source of this insertion was found within the intron sequence between the EC2 and TM exons, and the flanking nucleotides do consist of appropriate GT-AG junctional splice sequences.45

Physical map of the FcγRIIc-specific transcripts expressed in human NK cells. Sequence analysis of 16 cDNA clones obtained from four NK cell samples revealed the presence of four different alternatively spliced FcγRIIc-specific transcripts (IIc1-c4). IIc1 was identical with the already described FcγRIIc isoform; IIc2 transcript had a 14-bp insertion at the junction between the C2 and C3 exons; the IIc3 transcript had spliced out both the C1 and C2 exons; and IIc4 had an 85-bp insertion between the EC2 and TM exons and both the C1 and C2 exons spliced out.

Physical map of the FcγRIIc-specific transcripts expressed in human NK cells. Sequence analysis of 16 cDNA clones obtained from four NK cell samples revealed the presence of four different alternatively spliced FcγRIIc-specific transcripts (IIc1-c4). IIc1 was identical with the already described FcγRIIc isoform; IIc2 transcript had a 14-bp insertion at the junction between the C2 and C3 exons; the IIc3 transcript had spliced out both the C1 and C2 exons; and IIc4 had an 85-bp insertion between the EC2 and TM exons and both the C1 and C2 exons spliced out.

Predicted aa sequence of the FcγRIIc1-4 isoforms as compared with the previously described FcγRIIa1, b2, and c isoforms. Four representative FcγRIIc isoforms were identified and the translated sequence is shown in comparison to FcγRIIa1. The exon borders are demarcated by vertical lines and the numbering follows the aa position as previously described.20 The dashes represent sequence identity with the FcγRIIa1 isoform, the pluses represent deleted aa, and the stars indicate a stop codon. At positions 107, 120, and 161 unique changes in the aa sequence of FcγRIIc-specific isoforms are indicated. The ITAM within FcγRIIa and IIc sequences encompasses aa 254-272. The sequence data are available from GenBank under accesion numbers: U90938-U90941.

Predicted aa sequence of the FcγRIIc1-4 isoforms as compared with the previously described FcγRIIa1, b2, and c isoforms. Four representative FcγRIIc isoforms were identified and the translated sequence is shown in comparison to FcγRIIa1. The exon borders are demarcated by vertical lines and the numbering follows the aa position as previously described.20 The dashes represent sequence identity with the FcγRIIa1 isoform, the pluses represent deleted aa, and the stars indicate a stop codon. At positions 107, 120, and 161 unique changes in the aa sequence of FcγRIIc-specific isoforms are indicated. The ITAM within FcγRIIa and IIc sequences encompasses aa 254-272. The sequence data are available from GenBank under accesion numbers: U90938-U90941.

The aa translation of these clones (Fig 6) revealed several differences in the aa sequence of the FcγRIIc isoforms isolated from NK-cell preparations, as compared with the previously described FcγRII sequences. For example, at aa 107, because of a point mutation, an arginine (R) found in all FcγRII isoforms was changed to a lysine (K) in the IIc2 and IIc4 isoforms. This was found in all five sequenced cDNA clones from two individuals. Furthermore, at aa 120 in the IIc3 sequence, four out of seven cDNA clones had an isoleucine (I) instead of a threonine (T). This change was found in two different individuals and may suggest the presence of another allelic form of FcγRIIc. At position 161 all of the IIc isoforms had a tyrosine (Y) instead of a phenylalanine (F). These changes may result in differences in ligand binding specificities of the newly described isoforms.

Identification of an FcγRIIc allelic polymorphism.

Following translation of the cDNA sequences, an additional allelic polymorphism of FcγRIIc was detected in exon 3 (EC1) at aa position 13, with either a CAG = Gln or aTAG = Stop Codon (STP). This results in either a functional open reading frame (ORF) or a null allele (STP; Fig6). This observation has been previously reported for the FcγRIIC gene.20 To detect the potential distribution of the two allelic forms among the four NK cell donors, we designed allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) probes based on the polymorphic sequence in EC1. DB analyses of the full-length PCR products generated from the four human NK-cell preparations using ORF and STP probes (Fig1) determined that A-NK1 and λgt10 donors were homozygous for STP (STP/STP), A-NK2 was homozygous for ORF (ORF/ORF) and A-NK3 was heterozygous (ORF/STP) (Table1).

Results of Southern Blot Analyses on RT-PCR Products From Four NK-Cell Preparations Using ASO and ISO

| Source . | Primers . | STP . | ORF . | C1 . | C2 . | C3 . | C4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λgt10 | StC-II | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| ANK1 | StC-IIA | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| ANK2 | StC-IIA | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| ANK3 | StC-IIA | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Source . | Primers . | STP . | ORF . | C1 . | C2 . | C3 . | C4 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λgt10 | StC-II | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| ANK1 | StC-IIA | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| ANK2 | StC-IIA | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| ANK3 | StC-IIA | + | + | + | + | + | + |

We also designed isoform specific oligonucleotide (ISO) probes (c1-, c2-, c3-, and c4-probes; Fig 1) to detect the distribution of the FcγRIIc isoforms within the same RT-PCR amplifications. Results in Table 1 suggested that distribution of the FcγRIIc isoforms was donor-dependent. RT-PCR amplification generated from donor A-NK2 resulted in only one major band detected by gel electrophoresis (Fig 4) and consisted exclusively of the FcγRIIc1 isoform (confirmed by DB analysis with ISO probes and cloning results). The other three donors expressed all four isoforms. Multiple bands were detected in their RT-PCR amplifications (Fig 4), and these findings were confirmed by DB analysis with ISO probes (Table 1).

Transfection of FcγRIIc isoforms in Jurkat cells.

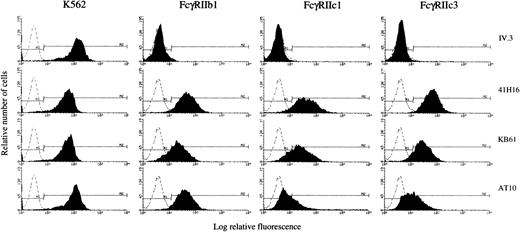

We further analyzed the ability of representative FcγRIIc cDNAs to be expressed as proteins in stable Jurkat transfectants. Cells transfected with FcγRIIb1 cDNA were used as a positive control; cells transfected with the pcDNA3 vector were used as a negative control (mock, data not shown). Following selection, the transfectants were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD32 expression with a panel of four anti-CD32 MoAbs: IV.3 (FcγRIIa-specific), 41H16 (FcγRIIb and FcγRIIa HR-specific), KB61, and AT10 (FcγRIIa and FcγRIIb-specific). Results were compared with mouse IgG isotype control binding and to the binding pattern of the anti-CD32 MoAbs to the K562 cell line. Two of the FcγRIIc isoforms and the FcγRIIb1 cDNAs were successfully expressed in Jurkat cells. As shown in Fig 7, the K562 cell line was positive with all four anti-CD32 MoAbs, whereas the FcγRIIb1 transfectant was recognized by 41H16, KB61, and AT10 at equal levels (60% to 90%), but not by IV.3 as expected. The cells transfected with FcγRIIc1 and FcγRIIc3 cDNAs stained positively with 41H16 and KB61 (60% to 90% positive cells). The transfectants were negative for IV.3 binding but interestingly stained poorly with the AT10 MoAb as compared with the FcγRIIb1 transfectants. The AT10 antibody was previously described to recognize both FcγRIIa and FcγRIIb isoforms.46 These results indicate that FcγRIIc1 and FcγRIIc3 isoforms have a unique staining pattern with the tested anti-CD32 MoAbs, distinct from that described for the previously characterized FcγRIIa and FcγRIIb isoforms.

Flow cytometric analysis of FcγRIIc1 and IIc3 expression in stable transfections. K562 cell line or Jurkat cells transfected with full-length cDNAs encoding FcγRIIb1, FcγRIIc1, and FcγRIIc3 were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence staining with four anti-CD32 MoAbs (filled histograms) or with a mouse IgG isotype control (dotted line), followed by staining with FITC-GAMIgG.

Flow cytometric analysis of FcγRIIc1 and IIc3 expression in stable transfections. K562 cell line or Jurkat cells transfected with full-length cDNAs encoding FcγRIIb1, FcγRIIc1, and FcγRIIc3 were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence staining with four anti-CD32 MoAbs (filled histograms) or with a mouse IgG isotype control (dotted line), followed by staining with FITC-GAMIgG.

FcγRIIc expression on NK cells varies among donors and correlates with the allelic polymorphism of FcγRIIC.

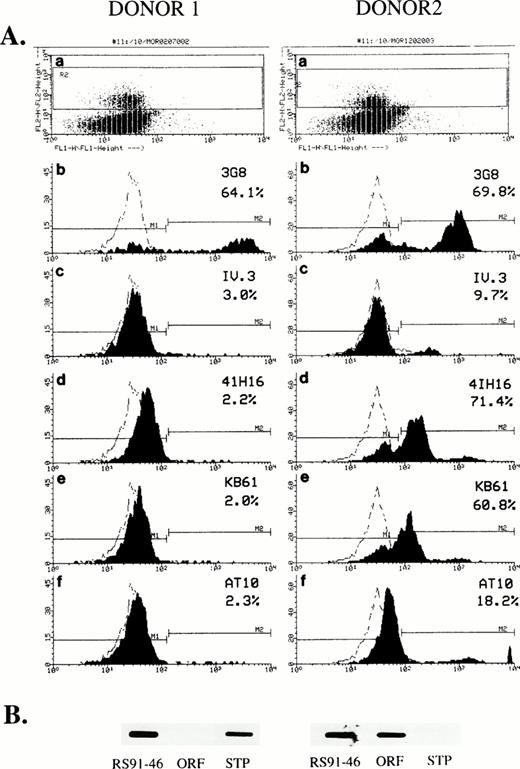

In view of the novel molecular findings and the unique MoAb staining pattern of FcγRIIc detected on Jurkat transfectants, we looked for CD32 expression on fresh NK cells from additional donors. In these experiments, PBMCs were analyzed by two color flow cytometry for expression of CD32 and CD16 on CD56+ cells (a marker that is expressed on most NK cells) and compared with the binding of mouse IgG1 isotype control. Results shown in Fig8A identify different patterns of CD32 expression and staining in two normal individuals. With donor 1, 64% of CD56+ cells were also CD16+, but no CD32 expression was detected by the four anti-FcγRII MoAbs used. In contrast, with donor 2, a high level of CD32 expression on CD56+ NK cells was detected. Notably, the percentages of CD56+/CD32+ cells and CD56+/CD16+ cells in this donor were comparable. In addition, the pattern of CD32 staining with the four anti-CD32 MoAbs was comparable to that found in FcγRIIc Jurkat transfectants: high levels of staining with the 41H16 and KB61 MoAbs, low levels of staining with AT10 and IV.3.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD32 expression on human NK cells and its correlation with the allelic polymorphism of FcγRIIC. (A) PBLs isolated from donor 1 and donor 2 were analyzed by using PE-conjugated anti-CD56. Gated CD56+ cells (R7 box, panels a) representing NK-cell population, were then assessed for their levels of CD16 (3G8, panels b), or CD32 expression (IV.3, panels c; 41H16, panels d; KB61, panels e; and AT10 panels f). Percentages of positive CD16 and CD32 cells are shown for each histogram and are compared with the binding of mIgG isotype control. (B) SB analyses of FcγRIIc-specific RT/PCR amplifications using RS91-46 and ASO probes to detect the genotype of the two donors. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD32 expression on human NK cells and its correlation with the allelic polymorphism of FcγRIIC. (A) PBLs isolated from donor 1 and donor 2 were analyzed by using PE-conjugated anti-CD56. Gated CD56+ cells (R7 box, panels a) representing NK-cell population, were then assessed for their levels of CD16 (3G8, panels b), or CD32 expression (IV.3, panels c; 41H16, panels d; KB61, panels e; and AT10 panels f). Percentages of positive CD16 and CD32 cells are shown for each histogram and are compared with the binding of mIgG isotype control. (B) SB analyses of FcγRIIc-specific RT/PCR amplifications using RS91-46 and ASO probes to detect the genotype of the two donors. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

To further test the hypothesis that individuals lacking expression of CD32 on their NK cell are homozygous for STP allele, we investigated the correlation between the level of CD32 expression and the genotype of these two donors. RT-PCR experiments on RNA obtained from NK cells from these two donors were performed using FcγRIIc-specific primers (STC-3′IIA); the amplified products were further analyzed by DB using ASO probes. As shown in Fig 8B, donor 1 (no detectable CD32 expression) was found to be homozygous for STP (STP/STP), whereas donor 2 (high levels of CD32 expression) was homozygous for ORF (ORF/ORF). We can therefore explain the previous lack of detection of CD32 on NK cells, as a result of donor variability due to an allelic polymorphism within the FcγIIC gene, in conjunction with the use of inappropriate anti-CD32 MoAbs for staining.

FcγRIIc expressed on human NK cells is a protein of approximately 40 kD.

To determine the biochemical features of CD32 expressed on human NK cells, we performed immunoprecipitations from biotinylated cell lysates obtained from U937 cells, as well as from PBL and highly purified NK cells isolated from donor 2 using 41H16 MoAb or a mouse IgG2a as negative control. As shown in Fig 9, a protein of approximately 40 kD was specifically precipitated with the anti-CD32 MoAb from the NK-cell preparation and PBL and was comparable in size with the proteins detected in U937 lysates. The number of cells used to generate lysates was comparable for each cell source. In addition, no material was adsorbed by the beads coupled with the isotype control (mIgG2a). These biochemical findings provide further evidence that the proteins on NK cells detected by flow cytometry with certain anti-CD32 MoAbs are indeed FcγRII.

Immunoprecipitation of FcγRIIc from highly purified NK cells. Lysates generated from biotinylated 2 × 106 PBL, NK cells, or U937 cells were incubated with 41H16-, IV.3-, or mIgG2a-coated sepharose-GAM beads o/n at 4°C, eluted by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDP membranes, and incubated with HRP-neutravidin. The bands were detected by ECL. Results represent one experiment out of two performed. The molecular markers are shown on margins.

Immunoprecipitation of FcγRIIc from highly purified NK cells. Lysates generated from biotinylated 2 × 106 PBL, NK cells, or U937 cells were incubated with 41H16-, IV.3-, or mIgG2a-coated sepharose-GAM beads o/n at 4°C, eluted by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDP membranes, and incubated with HRP-neutravidin. The bands were detected by ECL. Results represent one experiment out of two performed. The molecular markers are shown on margins.

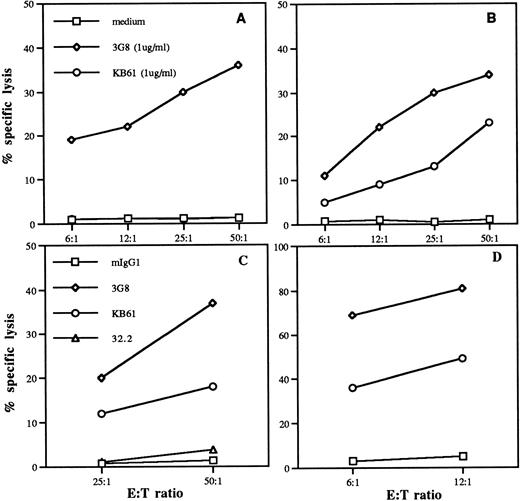

FcγRIIc expression on NK cells mediates rADCC.

To investigate the functional potential of FcγRII expressed on NK cells in certain individuals, we analyzed the role of CD32 ligation in triggering cytotoxic events. The results were compared with the cytolysis triggered through CD16 on the same cells. Fresh, highly-purified NK cells isolated from donors 1 and 2, as well as A-NK cells generated from donor 2, were used in rADCC assays in the presence of intact anti-CD32 MoAb KB61, anti-CD16 MoAb, 3G8 or anti-CD64 MoAb 32.2 against FcR+ target P815. All of these MoAbs were mIgG1 and as a negative control, rADCC in the presence of a nonspecific mIgG1 MoAb was also assessed. Results in Fig10 show that both fresh or IL-2–activated NK cells isolated from donor 2 (Fig 10B through 10D) could be triggered to kill P815 through either CD16 or CD32, although the killing efficiency of A-NK cells was significantly higher (Fig10D). In contrast, NK cells isolated from donor 1 (Fig 10A), which lack CD32 expression, were cytotoxic against the P815 target only when triggered via CD16. Addition of anti-CD64 MoAb 32.2 (Fig 10C) did not result in killing of the target cells, further confirming the absence of contaminating monocytes in the NK-cell preparations. These findings provide evidence that CD32 on NK cells is a functional molecule.

Comparison of rADCC induction through CD16 and CD32 expressed on human NK cells. Fresh, highly-purified NK cells from donor 1 (A) and donor 2 (B and C) as well as A-NK cells generated from donor 2 (D) were tested in the presence of KB61 anti-CD32 (1 μg/mL) or 3G8 anti-CD16 (1 μg/mL) for their ability to kill the FcP+target P815 in a 4-hour 51Cr-release cytotoxicity test at the indicated E:T ratios. NK cells from donor 2 were also tested in the presence of 32.2 anti-CD64 (1 μg/mL) (C).

Comparison of rADCC induction through CD16 and CD32 expressed on human NK cells. Fresh, highly-purified NK cells from donor 1 (A) and donor 2 (B and C) as well as A-NK cells generated from donor 2 (D) were tested in the presence of KB61 anti-CD32 (1 μg/mL) or 3G8 anti-CD16 (1 μg/mL) for their ability to kill the FcP+target P815 in a 4-hour 51Cr-release cytotoxicity test at the indicated E:T ratios. NK cells from donor 2 were also tested in the presence of 32.2 anti-CD64 (1 μg/mL) (C).

DISCUSSION

Three classes of receptors for the Fc domain of IgG (FcγRI, FcγRII, and FcγRIII) are known to provide a critical link between the humoral and the cellular compartments of the immune system. Following interaction with IgG, a large array of biologic responses are triggered, such as phagocytosis, endocytosis, ADCC, and cytokine release. A total of eight genes have been described for the FcγRs, and further significant transcript heterogeneity results from alternative splicing. In addition, allelic polymorphisms have been described for FcγRIa,47 FcγRIIa,21FcγRIIc,20 FcγRIIIA,48 and FcγRIIIB.49 Some of these polymorphisms result in significant functional differences,50-52 whereas others do not appear to influence the functional capabilities of these receptors or to result in obvious clinical manifestations.52,53 Human FcγRII (CD32), the low affinity receptor for IgG, has been characterized as a 40-kD glycoprotein, with a putative protein core of 36 kD16-18; it is the most broadly distributed FcγR, and numerous reports have previously described coexpression of FcγRIIA, B, and C gene products in hematopoietic cells.18 33

The results presented in this study provide conclusive evidence that human NK cells express significant levels of FcγRII. In certain individuals, CD32 is expressed on 70% to 80% of their NK cells, at levels comparable to those observed for CD16. The molecular characterization of CD32 isoforms expressed by NK cells revealed that these cells express FcγRIIc isoforms. No transcripts from the FcγRIIA or FcγRIIB genes have been detected, to date, in at least 10 individuals studied, suggesting that NK cells might be relatively unique among hematopoietic cells and only express FcγRIIc isoforms. Four FcγRIIc transcripts were identified, three encoding transmembrane proteins (IIc1, IIc2 and IIc3), and one encoding a putative soluble form (IIc4). The variability in detection of CD32 expression among donors was found to be related to two main factors: (1) an allelic polymorphism, in the EC1 domain of FcγRIIC and (2) a unique pattern of recognition by anti-CD32 MoAbs. These two factors, we believe, are responsible for previous failures to find CD32 on NK cells. The data in this paper show that although certain individuals express only CD16 on their NK cells, others express both CD32 and CD16. The allelic polymorphism results either in a null allele (STP) or a functional one (ORF). An individual who exhibited a high level of CD32 expression was found to be homozygous for ORF/ORF, whereas an individual whose NK cells were CD32 negative was homozygous for STP/STP. We have begun to extend these studies and have been able to identify an additional 5 individuals (out of 10 more tested) that express high levels of CD32 on their NK cells. The precise correlation between the genotypic form (heterozygous v homozygous for STP and/or ORF) and variable (high v low) phenotypic expression of FcγRIIc in these donors remains to be established. Immunoadsorbtion with 41H16 MoAb from CD32+ NK-cell lysates revealed a protein of approximately 40 kD, comparable in size with the material precipitated from PBLs and slightly smaller than the proteins adsorbed from U937 cells. This is in good agreement with a previous report providing evidence of discrete differences in gel migration among CD32 isoforms immunoprecipitated from different cell types, including from U937 cell lysates. The proteins ranged from 37 to 42 kD, and that was shown to be dependent on both isoform type and the state of glycosylation.54

In addition, we show that NK-cell populations that express CD32 as well as CD16 may mediate lytic events through either receptor. Interestingly, the levels of killing against P815 when triggered through CD16 were greater as compared with those triggered through CD32, and this is probably related to differences in the levels of expression of these two FcγRs on the NK cells used. The mean fluorescence intensity obtained using the anti-CD32 MoAb KB61 is significantly lower than that obtained with anti-CD16 MoAb 3G8 and could reflect either lower levels of expression of CD32 than CD16, or that recognition of CD32 by KB61 is not optimal. In any event, these studies show conclusively that significant functional lytic activity can be triggered through CD32 on NK cells.

Transfection experiments using FcγRIIc1 and IIc3 revealed that these full-length cDNAs encode functionally expressed proteins and that they display a unique pattern of reactivity with a set of anti-CD32 MoAbs. Most significantly these isoforms were recognized poorly by AT10 (described to be a pan anti-FcγRII MoAb) and IV.3, a commonly used anti-CD32 MoAb. The NK-cell–derived FcγRIIc isoforms were best recognized by 41H16 and KB61, which are known to predominantly recognize FcγRIIb isoforms.46 Most of the studies describing the lack of CD32 expression on NK cells used either IV.3 or AT10 MoAbs. One study in addition to ours, that described CD32+ NK cells, used the 41H16 MoAb. Because it appears that human NK cells only express FcγRIIc, the appropriate antibodies to detect this isoform are 41H16 and KB61.

Sequence analyses of the FcγRIIc isoforms isolated from human NK cells identified several aa differences in the EC2 domain, as compared with the previously described FcγRII isoforms. At position 107, an arginine (R) was changed to a lysine (K) in the FcγRIIc2 and FcγRIIc4 isoforms, and at position 120 a threonine (T) found in FcγRIIa, b and c was changed to an isoleucine (I) in four out of seven FcγRIIc3 clones. In addition, all FcγRIIc isoforms were found to have a tyrosine (Y) in position 161 instead of a phenylalanine (F) found in FcγRIIa and FcγRIIb. It is possible that these unique changes occurring at aa 161, as well as aa 107 and aa 120 for some FcγRIIc isoforms, might influence receptor-ligand interactions. Hulett et al18 previously showed that for FcγRII, EC2 is the principal domain involved in IgG binding, with the 154-161 aa region playing a direct role in ligand binding, and indirect binding contributions by the 111-114 and 130-135 aa regions. The relative inability of the AT10 MoAb to recognize the FcγRIIc isoforms may correlate with the aa change at position 161, as this was the only change common to all IIc isoforms sequenced. If this proves to be the case, it should be possible to use this region to generate new MoAbs that would be specific for FcγRIIc. Although it appears that these changes may reflect allelic polymorphisms of the FcγRIIC gene, it is also possible that some of these sequences represent transcripts from an as yet unidentified FcγRII gene.

Transcripts for the FcγRIIc1 isoform have been detected in monocytes, macrophages, and PMNs, as well as in several tumor cell lines,19,33 and we extend this to include its expression by NK cells. Detailed characterization of the ligand-binding specificities or functional abilities of the FcγRIIc1 isoform have not been reported, but IIc transcripts would be expected to share binding specificities with the FcγRIIb isoforms (ie, IgG3 ≥ IgG1 > IgG4 ≫ IgG2)55 with potential unique binding features caused by the aa changes detected within EC2 of FcγRIIc. This is an important point to address in the case of NK cells, because they coexpress FcγRIIIa, with different ligand binding specificities (IgG3 = IgG1 >>> IgG2 = IgG4).17The expression of FcγRIIc on NK cells of certain individuals at levels comparable to CD16 might create an alternative IgG ligand binding specificity that may have functional significance.

The FcγRIIc1 isoform is likely to be a triggering molecule, because its cytoplasmic tail, homologous with the FcγRIIa isoform, contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM; Fig6),56 and this is confirmed by our rADCC results using both fresh or IL-2–activated NK cells. FcγRIIIa on NK cells was shown to be a potent triggering molecule, but for efficient expression and signaling requires the coassociation with TCR ζ- and/or FcεRI γ-chains.10,57 It is possible that the FcγRIIc1 might function by itself but also may associate with these chains in a manner similar to FcγRIIa, which has been shown to physically and functionally associate with the FcεRI γ-chain.28 29This may lead to a complex interaction between FcγRIIc1 and FcγRIIIa when both are expressed on the same cell. Thus, in addition to an alternative ligand binding specificity, IIc1 might also offer an alternative signal transduction pathway, and current studies are ongoing to address these issues.

In contrast to the FcγRIIc1 isoform, the IIc2 and IIc3 isoforms do not contain the ITAM sequence in their cytoplasmic tails. Thus, while the IIc2 and IIc3 isoforms might not bear intrinsic triggering properties, they may have a significant role in cross-regulating signaling by way of FcγRIIIa/FcγRIIc1 on NK cells. They may serve to focus immune complexes on the cell surface and trigger FcγRIIIa/FcγRIIc1, as has been shown in the case of FcγRIIIb and FcγRIIa on PMNs.58 59

The IIc4 transcript in NK cells represents a previously undescribed potential soluble form of FcγRIIc. This transcript results from the alternative usage of an EC exon that encodes a stop codon before the TM domain. We have obtained and sequenced one full-length IIc4 clone, but previous cloning experiments with shorter, non–full-length, RT-PCR products from several NK-cell preparations generated additional IIc4 cDNA clones, indicating that this isoform is widely expressed. The functional significance of this isoform in NK cells remains to be established. The soluble FcγRs, also known as IgG-binding factors, have been found in supernatants of activated FcR+lymphocytes and phagocytes and were determined to have immunoregulatory properties.60 sFcγRs may be encoded by all three FcγR genes, and several mechanisms have been described for their generation including (1) a premature stop codon in EC3 for the b1 and c FcγRI cDNAs61; (2) alternative splicing with deletion of the TM sequence for the FcγRIIa2 cDNA21; or (3) proteolytic cleavage of membrane FcγRIII.62

In summary, we have characterized four FcγRIIc isoforms, three of them novel, in human NK cells. There appears to be a great deal of heterogeneity among individuals in the expression of these isoforms because of complex factors including the presence of null alleles for each of the isoforms described in certain donors, which results in lack of CD32 expression, as well as differential binding of anti-CD32 MoAb to FcγRIIc caused by the aa differences observed in the EC2 domain of the FcγRIIc isoforms. It is important to emphasize that in all of the individuals we have examined to date, their NK cells mainly express products of the FcγRIIC gene. The absence of FcγRIIa or FcγRIIb on NK cells further shows that the CD32 expression observed on these cell preparations in not caused by contaminating monocytes or B cells. Reports that NK cells fail to express CD32 should be reconsidered in the light of these new data. In addition, the presence of FcγRIIc on NK cells might provide an expanded ligand binding specificity beyond that of the FcγRIIIa repertoire. CD32 on NK cells appears to be triggering molecule, and the functional relevance of the presence of two FcγRs on the surface of NK cells in some individuals remains to be established.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Theresa Whiteside for providing valuable access to the UPCI Immunologic Monitoring and Diagnostic Laboratory facilities, and Dr Nikola Vujanovic and Dr Shighe Nagashima for providing us with highly purified A-NK cell populations. We also thank Drs Jeffrey Ravetch, Steven Ziegler, and Jan van de Winkel for the kind gift of reagents used in these studies. We thank Dr Huiling He for assistance and advice with the sequencing studies, Dewayne Falkner for excellent technical support, and Alexis Styche and Robert Lakomy for the flow cytometric data acquisition.

Supported in part by R03 TW00480 grant. During the performance of this study, Dr Diana Metes was a recipient of a Fogarty International Fellowship.

Address reprint requests to Penelope Morel, MD, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, W1057 Biomedical Science Tower, 200 Lothrop St, Pittsburgh, PA, 15213.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

![Fig. 3. Southern blot analysis to determine the FcγRII isoforms expressed by human NK cells. RT-PCR with the FcγRIIa/c-specific primer pair on three A-NK cell samples, U937 and K562 cell lines (positive control), or Molt4 (negative control) was performed as described. The Southern blots were probed with oligonucleotides specific for all the FcγRII isoforms (RS91-46; [A]), for FcγRIIa (HR; [B] and LR; [C]) and for FcγRIIc (IIB; [D]), and cell-specific transcripts of the expected sizes were detected with each probe.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2369/3/m_blod4070803.jpeg?Expires=1764989779&Signature=Nv4kZsmW-XYUEuX8Fohx1SPwjR4aBYtJKmw5VtxQuf9ByXnebvIvoCPrnhuB2EUxhuaD~By~xtsc6kmJqITeOmrT4654PbZeDwqk~fniLMJ-NqufV4tbIWXV0gn4YPC~ifo-sYpcyW-ksTY7fHkP6H~sybcvmvxy7swKsh6TW73qeQYjz3TmWi3h3YupHq2hgW-M5bv2I~L0iU5Jog1ZBOtH1jGrrolMg2bBgD4xaFz-NzGtZfNyrGjKmAjXsdllJo-zrOQaqc~4bfmLedzbgRa9sM6jWzluHBOi5XQnAyu2FQ0UFUMQmSBJz8WxiN28kSU14UolwY3L8Meo1foy3w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal