To The Editor:

Adenovirus vectors are attractive vehicles for clinical gene transfer as these replication-deficient vectors exhibit wide tissue tropism, infection of both replicating and nonreplicating cell types, and provide highly efficient expression of transgenes linked to appropriate promoters.1-3 Consequently, such vectors are now in widespread use in clinical gene therapy trials, particularly for cancer immunotherapy.

Nevertheless, adenoviral vectors infect primary human lymphoid tissue at low efficiency4,5 reflecting low levels of adenoviral internalization receptors on the cell surface,6thus limiting the potential for treatment of human lymphoid malignancies. However, we and others have previously reported that adenovirus vectors can efficiently infect myeloma cell lines and to a lesser degree primary plasma cells.7,8 Furthermore, Cantwell et al6 showed that, in a majority of patients, chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells can be transfected with an adenovirus vector, albeit using a high multiplicity of infection. In contrast, as expected, lymphoma cell lines can only be infected at low efficiency.7

The cytokine interleukin-2 (IL-2) can mediate antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo by inducing lymphokine-activated killer cells and activating tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.9Serious side effects have proved a limitation to the clinical use of high-dose systemic IL-2 as an antitumor agent.10 To circumvent these side effects and to maintain high intratumoral concentrations of IL-2, attention has turned to the use of gene delivery systems to express IL-2 continuously within or around the tumor.11 Previous reports from our laboratories have shown sustained tumor regression and immune protection in mice injected with an E1, E3-deleted adenovirus carrying the human IL-2 (hIL-2) cDNA.12 Furthermore, others have reported regression of a murine plasmacytoma after transfection with the IL-2 gene.13

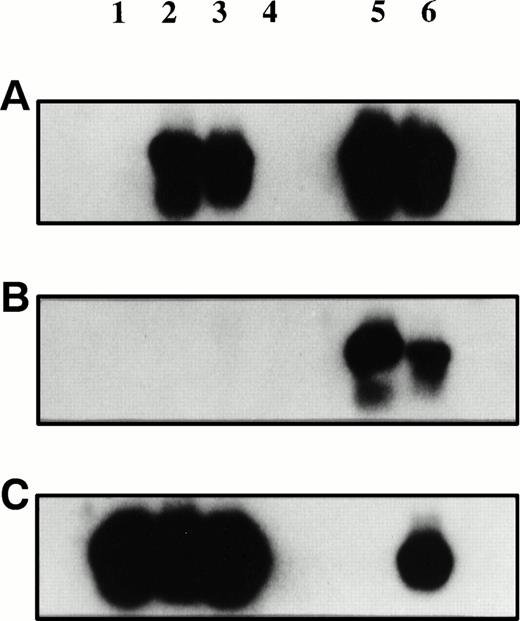

Plasmacytoma biopsy samples before and after injection of AdCAIL-2 were PCR-amplified using primers specific for AdCAIL-2 (A), Ad5 E1 (B), or B-actin (C). PCR products were detected using internal radiolabeled probes. Lane 1, tumor biopsy sample preinjection; lane 2, tumor biopsy sample 7 days postinjection; lane 3, tumor at autopsy; lane 4, negative control—mock DNA extraction from autopsy tumor; lanes 5 and 6, positive controls. No E1 sequences from wild-type adenovirus were detected in the tumor. In contrast, AdCAIL-2 was readily detected in the postinjection biopsy samples.

Plasmacytoma biopsy samples before and after injection of AdCAIL-2 were PCR-amplified using primers specific for AdCAIL-2 (A), Ad5 E1 (B), or B-actin (C). PCR products were detected using internal radiolabeled probes. Lane 1, tumor biopsy sample preinjection; lane 2, tumor biopsy sample 7 days postinjection; lane 3, tumor at autopsy; lane 4, negative control—mock DNA extraction from autopsy tumor; lanes 5 and 6, positive controls. No E1 sequences from wild-type adenovirus were detected in the tumor. In contrast, AdCAIL-2 was readily detected in the postinjection biopsy samples.

Encouraged by these findings we injected a patient with subcutaneous plasmacytomas with a clinical grade adenovirus expressing hIL-2 (AdCAIL-2) as part of an ongoing phase 1 trial of AdCAIL-2 in subcutaneous malignancy.14 Here we report the first example of successful in vivo adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into primary malignant plasma cells and demonstrate expression of the gene product for at least two weeks after infection.

A 46-year-old woman with chemotherapy refractory relapsed multiple myeloma developed cutaneous tumor metastases 5 months after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biopsy of an occipital tumor mass revealed malignant plasma cells consistent with a plasmacytoma. The patient was enrolled on a compassionate basis on a phase I study of direct injection of AdCAIL-2 into subcutaneous tumor metastases.

Construction of the adenoviral vector AdCAIL-2 and the clinical protocol have been described elsewhere.12 14 Briefly, a recombinant E1, E3-deleted Ad5 vector expressing hIL-2 was constructed in which the E1 region was substituted with an expression cassette containing the human cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter (HCMV), an hIL-2 cDNA (a gift of Dr Robert Ralston, Chiron Corp, Emeryville, CA), and the SV40 polyadenylation signal.

A baseline tumor biopsy sample was obtained from the patient following which a total of 1 × 1010 Plaque-forming units (pfu) of AdCAIL-2 in 1 mL of saline was administered in split dose via fine needle into the cutaneous occipital tumor, two other cutaneous lesions, and a left supraclavicular lymph node. A biopsy of the cutaneous occipital tumor mass was performed 1 week after the inoculation. We examined the biopsy specimens for evidence of the viral vector using sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based indicators of viral sequences. Oligonucleotide primers from the CMV promoter (5′ TTGCGAGTACATCAATGGGCGTGG3′) and from the hIL-2 mini cassette (5′ TGAGCATCCTGGTGAGTTTGGG3′) were used to detect the presence of AdCAIL-2. To detect wild-type adenovirus, primers spanning the deleted Ad5 E1 region were used (5′ TTATCTGCCACGGAGGTGT3′ and 5′CGGCGAGCGCCTTCTGGCGG3′). PCR products were run on ethidium gels and after Southern transfer were detected with radiolabeled internal probes. These PCR assays can detect 1.5 × 103 pfu (1.5 × 104 particles) of AdCAIL-2 and as few as 10 pfu of wild-type adenovirus respectively (not shown).

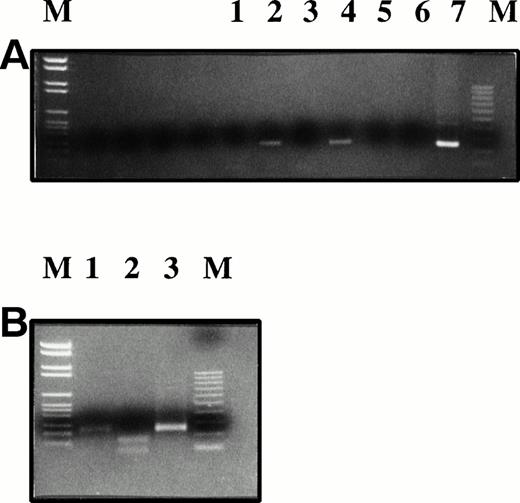

No Ad5 E1 sequence was detected in either the preinjection or postinjection tumor biopsy specimens (Fig 1). Saliva and blood screened by PCR for E1 sequences were also negative (not shown). No virus could be recovered by 7-day culture of lysed tumor cells on A549 cells (a cell line permissive for replication of wild-type adenovirus but not replication defective vectors). In contrast AdCAIL-2 sequences were readily detected in the postinjection biopsy specimen and in a second injected tumor site at autopsy 12 days after injection (Fig 1). By reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis, we next demonstrated that the tumor cells expressed hIL-2 mRNA, as shown in Fig2. The naturally occurring hIL-2 gene contains an Mwo I restriction enzyme site at bp 163 that the vector derived hIL-2 gene lacks because of a silent guanine to thymidine substitution. Thus, while PCR amplified IL-2 from normal donor T lymphocytes is digested by Mwo I the hIL-2 cDNA derived from the tumor and plasmid DNA control is not cut, confirming that IL-2 present in the tumor is primarily derived from the adenovirus.

RT-PCR for hIL-2 mRNA was performed and the products detected by ethidium gel. The PCR product was isolated (Geneclean) andMwo I restriction enzyme digestion shows that the hIL-2 amplified from the tumor is predominantly derived from the AdCAIL-2 vector. (A) RT-PCR for hIL-2. Lanes 1, 3, 5, and 6: negative controls; lane 2: tumor biopsy sample 7 days postinjection; lane 4: normal donor phytohemagglutinin-activated T lymphocytes; lane 7: AdCAIL-2 plasmid positive control. (B) PCR products from (A) were digested withMwo I. Lane 1: PCR product from tumor biopsy sample; lane 2: normal donor activated T cells; lane 3: plasmid control. The IL-2 in the tumor post injection is predominantly derived from AdCAIL-2 and does not digest with Mwo I.

RT-PCR for hIL-2 mRNA was performed and the products detected by ethidium gel. The PCR product was isolated (Geneclean) andMwo I restriction enzyme digestion shows that the hIL-2 amplified from the tumor is predominantly derived from the AdCAIL-2 vector. (A) RT-PCR for hIL-2. Lanes 1, 3, 5, and 6: negative controls; lane 2: tumor biopsy sample 7 days postinjection; lane 4: normal donor phytohemagglutinin-activated T lymphocytes; lane 7: AdCAIL-2 plasmid positive control. (B) PCR products from (A) were digested withMwo I. Lane 1: PCR product from tumor biopsy sample; lane 2: normal donor activated T cells; lane 3: plasmid control. The IL-2 in the tumor post injection is predominantly derived from AdCAIL-2 and does not digest with Mwo I.

Although successful adenoviral-mediated hIL-2 gene transfer into the plasmacytoma was observed, no regression of the lesion was seen clinically and, in contrast to our findings in other patients on this trial, no evidence for T-cell infiltration of the tumor nor of enhanced autologous lymphocyte proliferation to AdCAIL-2–transfected cellsin vitro was observed (A.K. Stewart, unpublished results, December 1997). This most likely reflects the immunosuppressed state and steroid-dependent condition of the myeloma patient (absolute CD4 count 65 × 106/L).

We conclude that adenovirus vectors can successfully mediate gene transfer in human plasmacytoma cells in vivo. Furthermore, vector-specific DNA can be detected for at least 12 days and expression of the adenovirus-derived transgene persists for at least 7 days postinjection. These results encourage further examination of the role of adenovirus vectors for genetic immunotherapy in patients with multiple myeloma.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal