Abstract

In recent pediatric trials of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), children with Down syndrome (DS) have had significantly more megakaryoblastic leukemia and have experienced better outcome than other children. To further characterize AML in DS, Children's Cancer Group Studies 2861 and 2891 prospectively studied demography, biology, and response in AML and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) of children with and without DS. These studies evaluated timing of induction therapy and compared postremission chemotherapy with marrow transplantation in 1,206 children. One-hundred eighteen (9.8%) had DS, a fourfold increase in 20 years. DS patients were younger, had lower white blood cell and platelet counts, more antecedent MDS, acute megakaryoblastic leukemia or undifferentiated AML, and an under-representation of chromosomal translocations (P < .001 for each variable). Four-year event-free survival in DS was 69% versus 35% in others (P < .001). Intensively timed induction conferred significantly higher mortality in DS patients; bone marrow transplantation offered no advantage. Conventional induction followed by chemotherapy achieved an 88%, 4-year, disease-free survival in DS patients versus 42% in others (P < .001). Megakaryoblastic leukemia was unfavorable in others but prognostically neutral in DS. AML in DS is demographically and biologically distinct from AML in other children. It is singularly responsive to conventional chemotherapy and may warrant even less therapy. The increasing proportion of DS patients with AML most likely reflects changes in attitudes about entering DS patients on AML trials and possibly increasing ability to distinguish megakaryoblastic leukemia from lymphoid leukemia.

BASED ON A mail survey in 1957, Krivit and Good1 concluded that, in the United States, children with Down syndrome (DS) had at least a threefold excess risk of developing acute leukemia. Barber and Spiers2 estimated that, in England and Wales, their excess risk was 10- to 100-fold. Recent analyses place their risk at a 10- to 20-fold increase.3-5

The decades between 1950 and 1980 brought considerable debate about whether leukemia in DS was predominantly lymphoid or myeloid.6 Ultimately, the consensus was that the ratio of lymphoid to myeloid leukemia in DS approximated that of the general pediatric population, ie, about four lymphoid to one myeloid.3-5

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the predominant form of leukemia in DS children under age 4 and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) dominates in older children.7,8 When megakaryoblastic leukemia (French-American-British [FAB] M7) was formally defined, M7 was recognized as the most common form of AML in children with DS.9,10 Children with DS have over a 400-fold excess risk of developing megakaryoblastic leukemia.10 Megakaryoblastic leukemia may present as a myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or it may superficially resemble ALL.11-14 In retrospect, some cases of megakaryoblastic leukemia in children with DS were misdiagnosed as ALL.11,13 14

In the 1960s and 1970s many children with DS and AML were not treated. By 1983, inclusion of children with DS in large cooperative group studies became standard practice. With few exceptions, these studies showed that children with DS have an outcome significantly better than other children with AML or MDS.15-18

This report describes AML/MDS in 118 children with DS registered on two sequential Children's Cancer Group studies, CCG-2861 and CCG-2891. The aims of these studies with respect to the DS subgroup were (1) to provide unselected, unbiased protocol-based therapy to children with DS and (2) to compare the demography, biology, and response to therapy of AML and MDS in children with DS with those of the other children registered on CCG-2861 and CCG-2891.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients from birth though 20 years of age with previously untreated AML or MDS were eligible for CCG-2861 or CCG-2891 after Institutional Review Board approval and written, signed consent. Between March 16, 1988 and October 12, 1995, 143 children registered on CCG-2861 and 1,126 on CCG-2891.19 20 Seventeen patients were ineligible. Forty-six patients were excluded from this analysis, 26 because they had second malignant neoplasms, 11 because they presented with isolated chloromas, and 9 because their DS status was unknown.

AML and MDS were classified according to the FAB criteria.9,21-23 Morphology, histochemistry, and institutional immunophenotype reports were reviewed centrally in 69% of cases. When central review was not available, institutional results were used. Methods and concordance have been described previously.24 Together, central and institutional review allowed FAB classification of 1,131 (94%) patients. Karyotypes performed on stimulated and unstimulated cultures were centrally reviewed in 53% of patients on CCG-2891 with 83% acceptance.

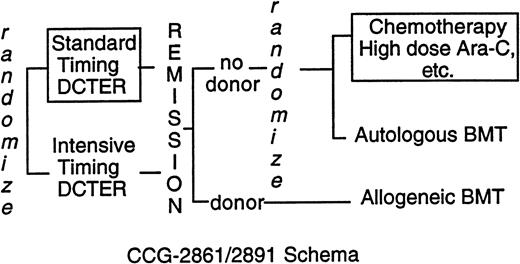

CCG-2861 was a pilot study testing the toxicity and efficacy of intensively timed induction therapy followed by 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide (4-HC)–purged autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT) or matched related allogeneic marrow transplant in children with previously untreated AML or MDS.19 CCG-2891, the successor Phase III randomized trial, compared intensively timed induction therapy with conventionally timed induction therapy. Postremission high-dose cytosine arabinoside (ara-C)–based chemotherapy was compared with 4-HC–purged autologous BMT or matched-related allogeneic BMT.20 The last cohort of 283 children on CCG-2891 received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after day 6 of intensively timed induction. This last cohort of patients is grouped with intensive-timing induction for comparisons of presenting features and outcome of induction therapy. When interim analyses showed excessive toxicity in children with DS, CCG-2891 excluded them first from allogeneic BMT (August 29, 1988) then autologous BMT and intensively timed induction (July 18, 1992). Thereafter, children with DS were assigned to standard-timing induction followed by chemotherapy (Fig 1). Because three fourths of the children with DS had treatment assigned, “as-treated” analyses rather than “intent-to-treat” analyses are presented. In the patients without DS, the intent-to-treat and as-treated analyses are essentially identical.20

The five-drug DCTER regimen consists of dexamethasone, 6 mg/m2/d by mouth (PO); ara-C, 200 mg/m2/d continuous infusion (CI); 6-TG, 50 mg/m2 PO twice daily; etoposide, 100 mg/m2/d CI; and rubidomycin, 20 mg/m2/d CI.20 Ara-C, etoposide, and rubidomycin are mixed in a single bag. Children under 3 years receive per kilogram dosing. One course of intensively-timed DCTER is given on days 0 to 3 and 10 to 13; standard-timing DCTER is given on days 0 to 3 and after marrow recovery if the day-14 marrow has <5% blasts or on days 14 to 17 if there are 5% blasts. Patients receive two courses of induction therapy. Transplant cytoreduction consists of busulfan 1 mg/kg every 6 hours for 16 doses. Graft-versus-host prophylaxis is with methotrexate. Chemotherapy consists of Capizzi II high-dose ara-C, 3 g/m2or 100 mg/kg 3-hour intravenous infusion every 12 hours four times on days 0 and 1 and days 7 and 8; and L-asparaginase, 6,000 U/m2 or 200 U/kg intramuscular at 42 hours. After marrow recovery patients receive daily 6-TG with ara-C, 75 mg/m2and 5-azacytidine at 100 mg/m2 four times, and cyclophosphamide, 75 mg/m2 four times for 2 months. Treatment ends with a modified DCTER regimen. Central nervous system prophylaxis is with 7 doses of intrathecal ara-C. Boxed in regimens are those used for DS patients after July 18, 1996.

The five-drug DCTER regimen consists of dexamethasone, 6 mg/m2/d by mouth (PO); ara-C, 200 mg/m2/d continuous infusion (CI); 6-TG, 50 mg/m2 PO twice daily; etoposide, 100 mg/m2/d CI; and rubidomycin, 20 mg/m2/d CI.20 Ara-C, etoposide, and rubidomycin are mixed in a single bag. Children under 3 years receive per kilogram dosing. One course of intensively-timed DCTER is given on days 0 to 3 and 10 to 13; standard-timing DCTER is given on days 0 to 3 and after marrow recovery if the day-14 marrow has <5% blasts or on days 14 to 17 if there are 5% blasts. Patients receive two courses of induction therapy. Transplant cytoreduction consists of busulfan 1 mg/kg every 6 hours for 16 doses. Graft-versus-host prophylaxis is with methotrexate. Chemotherapy consists of Capizzi II high-dose ara-C, 3 g/m2or 100 mg/kg 3-hour intravenous infusion every 12 hours four times on days 0 and 1 and days 7 and 8; and L-asparaginase, 6,000 U/m2 or 200 U/kg intramuscular at 42 hours. After marrow recovery patients receive daily 6-TG with ara-C, 75 mg/m2and 5-azacytidine at 100 mg/m2 four times, and cyclophosphamide, 75 mg/m2 four times for 2 months. Treatment ends with a modified DCTER regimen. Central nervous system prophylaxis is with 7 doses of intrathecal ara-C. Boxed in regimens are those used for DS patients after July 18, 1996.

Comparisons between the patients with DS and the others are made using a log rank statistic.25 Comparisons of prognostic factors among subsets of patients are made using Yates adjusted χ2 tables.26P values are two sided. Actuarial estimates of survival, event-free survival (EFS), and disease-free survival (DFS) are calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method; 95% confidence intervals (CI95), by the method of Simon and Lee.27 28 EFS is the time from on study to induction failure, marrow relapse, or death. DFS is the time from the end of induction to marrow relapse or death. Relapse-free survival (RFS) is the time from the end of induction to marrow relapse or death caused by progressive disease (PD); censored are deaths from other causes, presumably treatment related. Not all patients had data for all comparisons. Hence, numbers vary in some analyses. Data sets were frozen in January 1996.

RESULTS

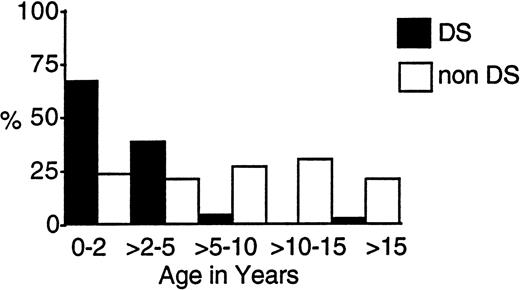

One hundred eighteen eligible patients (9.8%) with DS and 1,088 children without DS entered the two trials. Table 1 compares their presenting characteristics. Those with DS were significantly younger, with a median age of 1.8 years compared with 7.5 years. Figure2 shows that, whereas over 95% of those with DS were under 5 years, 40% of the others presented under age 5. Two patients with DS were under 2 months of age.

Presentation of AML or MDS in Children With and Without Down Syndrome (DS)

| . | N . | DS . | N . | No DS . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 118 | 1,088 | ||||

| Gender (M:F) | 0.76 | 1.10 | .058 | ||

| Race (white:other) | 1.29 | 1.65 | .134 | ||

| Age in yr (mean) | 1.8 | 7.5 | <.001 | ||

| Interquartile range | (1.3-2.4) | (2.5-13.2) | |||

| Hgb (g/dL) (median) | 8.5 | 8.2 | .99 | ||

| Interquartile range | (5.7-9.9) | (6.5-9.8) | |||

| WBC × 103/μL | 7.6 | 19.9 | <.001 | ||

| Interquartile range | (4.5-16.1) | (6.4-61.6) | |||

| Platelets × 103/μL | 29.0 | 52.0 | <.001 | ||

| Interquartile range | (15-51) | (26-110) | |||

| History of MDS | 23 | (20%) | 89 | (8%) | <.001 |

| FAB* | |||||

| MDS | 8 | (8%) | 39 | (4%) | .11 |

| FAB M0 | 10 | (10%) | 27 | (3%) | <.01 |

| FAB M1/2 | 10 | (10%) | 420 | (41%) | <.001 |

| FAB M3 | 2 | (2%) | 70 | (7%) | .08 |

| FAB M4/5 | 7 | (7%) | 383 | (37%) | <.0001 |

| FAB M6 | 3 | (3%) | 22 | (2%) | .863 |

| FAB M7 | 65 | (62%) | 56 | (6%) | <.001 |

| . | N . | DS . | N . | No DS . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 118 | 1,088 | ||||

| Gender (M:F) | 0.76 | 1.10 | .058 | ||

| Race (white:other) | 1.29 | 1.65 | .134 | ||

| Age in yr (mean) | 1.8 | 7.5 | <.001 | ||

| Interquartile range | (1.3-2.4) | (2.5-13.2) | |||

| Hgb (g/dL) (median) | 8.5 | 8.2 | .99 | ||

| Interquartile range | (5.7-9.9) | (6.5-9.8) | |||

| WBC × 103/μL | 7.6 | 19.9 | <.001 | ||

| Interquartile range | (4.5-16.1) | (6.4-61.6) | |||

| Platelets × 103/μL | 29.0 | 52.0 | <.001 | ||

| Interquartile range | (15-51) | (26-110) | |||

| History of MDS | 23 | (20%) | 89 | (8%) | <.001 |

| FAB* | |||||

| MDS | 8 | (8%) | 39 | (4%) | .11 |

| FAB M0 | 10 | (10%) | 27 | (3%) | <.01 |

| FAB M1/2 | 10 | (10%) | 420 | (41%) | <.001 |

| FAB M3 | 2 | (2%) | 70 | (7%) | .08 |

| FAB M4/5 | 7 | (7%) | 383 | (37%) | <.0001 |

| FAB M6 | 3 | (3%) | 22 | (2%) | .863 |

| FAB M7 | 65 | (62%) | 56 | (6%) | <.001 |

*FAB MDS includes only those who had not transformed to AML; M0 was included in CCG-2891 only (n = 111 for DS and 956 for others). Ninety-four percent of cases were classified by FAB criteria.

Age-related incidence of AML and MDS in children with and without DS treated on CCG-2861 and CCG-2891.

Age-related incidence of AML and MDS in children with and without DS treated on CCG-2861 and CCG-2891.

Table 1 shows that the presenting white blood cell (WBC) count and platelet count were significantly lower in those with DS and that a significantly greater percentage with DS had a history of antecedent myelodysplastic presentation (P < .001). Of those with AML, 62% of the children with DS had FAB M7, acute megakaryoblastic leukemia and 10% had undifferentiated AML (FAB M0), whereas the FAB M1 and M2 granulocytic and M4 and M5 monocytic subtypes each comprised about 40% of the AML/MDS among those without DS (P< .001).

Table 2 shows that, in the leukemic marrows, normal or abnormal karyotypes were equally distributed among those with and without DS. As a group, t(8;21), t(15;17), and rearrangements of chromosomal band 16q22 were significantly under-represented among those with DS (P < .001), whereas an additional nonconstitutional chromosome 21 occurred more frequently in the children with DS (P = .05), as do numerical abnormalities in the aggregate (P = .04, not shown).

Karyotype of AML or MDS in Children With and Without Down Syndrome (DS)

| Karyotype . | DS . | No DS . | P Value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | % . | N . | % . | ||

| Normal/constitutional | 13 | (26) | 106 | (24) | .97 |

| t(8;21); t(15;17); 16q22 | 1 | (2) | 106 | (24) | <.001 |

| 11q23 | 3 | (6) | 62 | (14) | .15 |

| −7; 7q- | 2 | (4) | 26 | (6) | .79 |

| +8 | 7 | (14) | 29 | (7) | .12 |

| +21 | 4 | (8) | 9 | (2) | .05 |

| Hyperdiploid | 4 | (8) | 12 | (3) | .13 |

| Hypodiploid | 1 | (2) | 6 | (2) | .63 |

| Other | 16 | (31) | 81 | (19) | .04 |

| Karyotype . | DS . | No DS . | P Value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | % . | N . | % . | ||

| Normal/constitutional | 13 | (26) | 106 | (24) | .97 |

| t(8;21); t(15;17); 16q22 | 1 | (2) | 106 | (24) | <.001 |

| 11q23 | 3 | (6) | 62 | (14) | .15 |

| −7; 7q- | 2 | (4) | 26 | (6) | .79 |

| +8 | 7 | (14) | 29 | (7) | .12 |

| +21 | 4 | (8) | 9 | (2) | .05 |

| Hyperdiploid | 4 | (8) | 12 | (3) | .13 |

| Hypodiploid | 1 | (2) | 6 | (2) | .63 |

| Other | 16 | (31) | 81 | (19) | .04 |

Results from 590 of 1,126 cases reviewed; 83% (488 of 590) were acceptable.

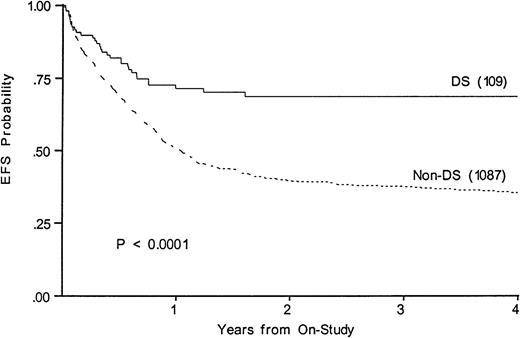

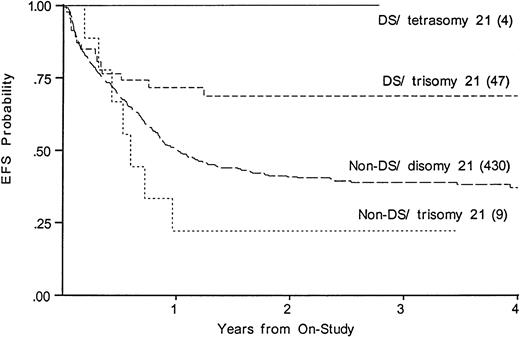

Figure 3 shows a 68% 4-year EFS in DS (CI95, 47%-84%) compared with 35% (CI95, 30%-41%) in those without (P < .0001). Survivals at 4 years are 67% in DS (CI95, 46%-83%) and 43% in others (CI95, 38%-49%). Table 3 lists events among the two groups according to induction therapy. Among DS patients with a determinate outcome (n = 110), intensive timing of induction was associated with a 32% mortality in the children with DS and 11% mortality in the others (P = .003). Standard timing achieved a 95% remission induction rate in those with DS, with 2.4% dying and 2.4% not entering remission. Only 64% of DS patients achieved remission with intensive timing. Among those without DS, intensive timing affected a significantly higher survival, EFS, and DFS than standard timing of induction (not shown).20 In contrast, intensive timing significantly reduced EFS (74% v 52%,P = .008) and survival in those with DS and had no effect on DFS (not shown). Conventional induction followed by chemotherapy achieved an 88%, 4-year DFS in DS patients versus 42% in others (P < .001).

Kaplan-Meier plot of actuarial EFS in children with and without DS on CCG-2861 and CCG-2891; numbers in parentheses indicate number at risk. EFS in DS is 68%; (CI95, 47%-84%); in non-DS, 35%; (CI95, 30%-41%).

Kaplan-Meier plot of actuarial EFS in children with and without DS on CCG-2861 and CCG-2891; numbers in parentheses indicate number at risk. EFS in DS is 68%; (CI95, 47%-84%); in non-DS, 35%; (CI95, 30%-41%).

Induction Outcome Among Children With and Without Down Syndrome

| . | DS . | No DS . | DS/No DS P Value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | (%) . | N . | (%) . | ||

| Standard timing | 85 | (100) | 300 | (100) | |

| Fail | 2 | (2) | 67 | (22) | <.001 |

| Die | 2 | (2) | 14 | (5) | .525 |

| CR | 81 | (95) | 219 | (73) | <.001 |

| Intensive Timing | 25 | (100) | 652 | (100) | |

| Fail | 1 | (4) | 65 | (10) | .520 |

| Die | 8 | (32) | 69 | (11) | .003 |

| CR | 16 | (64) | 518 | (79) | .108 |

| . | DS . | No DS . | DS/No DS P Value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | (%) . | N . | (%) . | ||

| Standard timing | 85 | (100) | 300 | (100) | |

| Fail | 2 | (2) | 67 | (22) | <.001 |

| Die | 2 | (2) | 14 | (5) | .525 |

| CR | 81 | (95) | 219 | (73) | <.001 |

| Intensive Timing | 25 | (100) | 652 | (100) | |

| Fail | 1 | (4) | 65 | (10) | .520 |

| Die | 8 | (32) | 69 | (11) | .003 |

| CR | 16 | (64) | 518 | (79) | .108 |

Excludes 130 patients with indeterminate outcome and 14 who switched induction therapy from standard to intensive timing midcourse when intensive timing was determined to be the superior regimen.

Table 4 shows postremission outcomes independent of induction therapy. DS patients had an overall RFS of 86% (CI95, 58%-97%) at 4 years compared with 57% (CI95, 49%-65%) in non-DS patients (P = .0002). Among those with DS, postremission treatment-related mortality is 6%; progressive disease, 8%. Among those without DS, treatment-related mortality is 15% and progressive disease, 15%. Table 4 shows that chemotherapy was the best postremission regimen among those with DS, and allogeneic BMT was best for those without DS. As with the intensive induction, the transplant regimens in DS were associated with unacceptably high mortality and no significant reduction in failure rate. Among those with DS, chemotherapy achieved a 91% RFS (CI95=38%-99%) compared with 52% among the others (P = .0001).

Postremission Outcomes at 4 Years Among Children With and Without Down Syndrome

| . | N . | DS Outcome . | %CI95 . | N . | No DS Outcome . | %CI95 . | P Value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postremission* | ||||||||

| RFS | 87 | 86% | (58-97) | 730 | 57% | (49-65) | .0002 | |

| DFS | 87 | 81% | (52-94) | 730 | 56% | (49-63) | .0002 | |

| Chemotherapy | 64 | 89% | (38-99) | 232 | 54% | (37-70) | .0001 | |

| Allogeneic BMT† | 3 | 33% | (6-79) | 153 | 71% | (61-80) | .17 | |

| Autologous BMT† | 6 | 67% | (30-90) | 199 | 56% | (48-64) | .49 |

| . | N . | DS Outcome . | %CI95 . | N . | No DS Outcome . | %CI95 . | P Value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postremission* | ||||||||

| RFS | 87 | 86% | (58-97) | 730 | 57% | (49-65) | .0002 | |

| DFS | 87 | 81% | (52-94) | 730 | 56% | (49-63) | .0002 | |

| Chemotherapy | 64 | 89% | (38-99) | 232 | 54% | (37-70) | .0001 | |

| Allogeneic BMT† | 3 | 33% | (6-79) | 153 | 71% | (61-80) | .17 | |

| Autologous BMT† | 6 | 67% | (30-90) | 199 | 56% | (48-64) | .49 |

*Based on as-treated analysis; excluded are 331 not in remission and 28 event/censored before entry.

Two-year DFS.

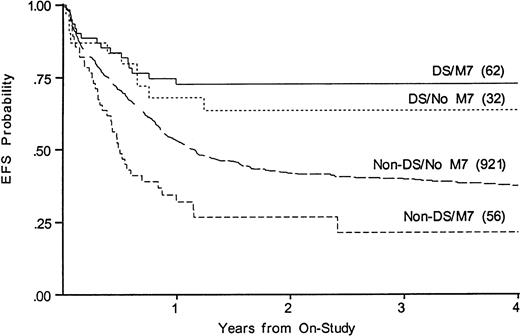

Whereas WBC at diagnosis is a significant predictor of outcome in non-DS patients, it is not predictive in DS patients, nor is antecedent MDS. Three DS patients were over age 5; two died of disease and one of toxicity. To determine whether the disparate proportions of M7 AML could account for the disparate results among those with and without DS, we compared outcomes among those with and without FAB M7 in DS and non-DS patients. Figure 4 shows that EFS for FAB M7 was significantly better among those with DS (73% v21% EFS, P < .001, for DS v non-DS patients). Among children with DS, M7 was not a significant variable (EFS 73% v64% for those with and without FAB M7). Among non-DS patients, FAB M7 was significantly unfavorable (EFS 21% v 37%, P = .001). FAB M0 was also over-represented among the DS, but was prognostically neutral in both DS and non-DS patients. Outcome for those with MDS was not significantly different from AML in either group (not shown).

Kaplan-Meier plot of actuarial EFS in children with and without DS with megakaryoblastic leukemia on CCG-2861 and CCG-2891; numbers in parentheses indicate number at risk. EFS in DS M7 is 73% (CI95, 41%-91%); DS non-M7, 64% (CI95, 31%-87%); non-DS M7, 21% (CI95, 6%-53%); non-DS non-M7, 37% (CI95, 32%-43%).

Kaplan-Meier plot of actuarial EFS in children with and without DS with megakaryoblastic leukemia on CCG-2861 and CCG-2891; numbers in parentheses indicate number at risk. EFS in DS M7 is 73% (CI95, 41%-91%); DS non-M7, 64% (CI95, 31%-87%); non-DS M7, 21% (CI95, 6%-53%); non-DS non-M7, 37% (CI95, 32%-43%).

We compared EFS, DFS, and survival among those DS patients with tetrasomy 21 in the leukemic clone to the DS patients with trisomy 21; among the non-DS patients, we compared trisomy 21 with disomy 21. Figure 5 shows that an extra chromosome 21 in the leukemic cells was not favorable among those without DS. Figure5 suggests that an additional nonconstitutional chromosome 21 in the leukemic clone may even be unfavorable; however, the log-rank statistic is compromised by early crossing of the curves (EFS, 36% disomy 21v 22% in trisomy 21). In the four DS patients with tetrasomy 21 there were no deaths, no failures, and no relapses.

Kaplan-Meier plot of actuarial EFS for DS and non-DS patients with and without trisomy 21 in the leukemic clone. EFS in DS, tetrasomy 21 is 100%; DS, trisomy 21, 69% (CI95, 45%-85%); non-DS trisomy 21, 22% (4%-66%); non-DS disomy 21 (CI95, 32%-46%).

Kaplan-Meier plot of actuarial EFS for DS and non-DS patients with and without trisomy 21 in the leukemic clone. EFS in DS, tetrasomy 21 is 100%; DS, trisomy 21, 69% (CI95, 45%-85%); non-DS trisomy 21, 22% (4%-66%); non-DS disomy 21 (CI95, 32%-46%).

To examine the effects of ara-C as a relatively isolated variable in CCG-2891, we compared the duration of therapy, morbidity, and mortality of the Capizzi II high-dose ara-C/L-asparaginase in patients with and without DS. Table 5 shows that the median duration of course, gastrointestinal and hepatic toxicity, and mortality were similar in DS and non-DS patients.

Toxicity of High-Dose Ara-C Postremission Therapy in CCG-2891

| Grade III or IV Toxicity . | DS . | No DS . | P Value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 68 . | (%) . | n = 236 . | (%) . | ||

| Liver | 2 | (3) | 11 | (5) | .78 |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 | (9) | 14 | (6) | .57 |

| CNS | 1 | (2) | 4 | (2) | .68 |

| Death | 1 | (2) | 12 | (5) | .34 |

| Median duration in days | 43 | 45 | |||

| Grade III or IV Toxicity . | DS . | No DS . | P Value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 68 . | (%) . | n = 236 . | (%) . | ||

| Liver | 2 | (3) | 11 | (5) | .78 |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 | (9) | 14 | (6) | .57 |

| CNS | 1 | (2) | 4 | (2) | .68 |

| Death | 1 | (2) | 12 | (5) | .34 |

| Median duration in days | 43 | 45 | |||

DISCUSSION

These two CCG studies showed that 9.8% of children with AML/MDS have DS, nearly twice that recently reported by the Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) and more than four times that previously reported by the CCG.4,15 This increase makes the ratio of AML to ALL in DS about one to one. The large proportion of DS patients in CCG-2861 and CCG-2891 probably results from greater recognition of megakaryoblastic leukemia, inclusion of MDS, and more registrations of children with DS on cooperative group trials. The high number may also reflect parental and medical responses to Baby Doe legislation in the United States and general recognition that AML in DS is treatable.29-31 A similar increase has been noted in the population-based Nordic AML study in which 13% of the pediatric AML patients had DS.32A big increase in incidence of AML among children with DS over the last two decades is unlikely.

The superior response of children with DS to AML therapy in CCG-2861 and CCG-2891 confirms earlier results.8,15,32-35Explanations for this outcome are that either the disease is different or the host is different or both. Compared with AML/MDS in children without DS, AML in those with DS presents at a younger age with lower WBC and platelet counts. In this study, all three patients over age 3 years died. Possibly they have a biologically different disease from younger patients. Morphology is most often megakaryoblastic or undifferentiated, and there is a high frequency of numerical karyotypic abnormalities and a paucity of translocations.14,16,36-40Among the infants without DS, 60% to 70% have monocytic, high tumor burden variants of AML with 11q23 abnormalities, a rare constellation of findings among the infants with DS.41 These findings suggest that the disease is different in the two populations.

Both the excessive toxicity of dose-intensive induction therapy and BMT postremission therapy in DS patients in these studies argue for host-related differences as well. Taub et al18 have proposed that the superior outcome in DS patients is a result of altered metabolism of ara-C. Dose-dependent alterations of folate pools and abnormally high levels of the active metabolite of ara-C in DS myeloblasts and Epstein Barr virus-transformed DS cell lines in the presence of ara-C occur in vitro.18 Altered ara-C metabolism may explain the responsiveness of AML to conventional therapy, but it should also contribute to excessive ara-C–mediated toxicity. However, our failure to find excessive toxicity in the high-dose ara-C postremission therapy among the children with DS does not support this hypothesis. It is possible that the dose of ara-C in the Capizzi II regimen is too high to discriminate between the DS and non-DS patients.

Other host factors may also contribute to the toxicity of intensive regimens. For example, children with DS experience excess toxicity with ALL induction therapy that does not involve the folate pathways,4,42,43 and children with DS have excess early mortality even when they do not have leukemia.44-48Additional host factors may involve metabolism of other drugs. DS patients have increased risk of steroid-induced and L-asparaginase–induced diabetes; they experience a vast spectrum of endogenous hematologic and immunologic disorders, congenital heart disease, and other factors as yet to be defined that render them vulnerable to disease-related and treatment-related morbidity and mortality.8 44-49

At one point, only 25% of transplant-eligible children with DS and leukemia actually underwent BMT.31,32 Demonstration that BMT could be successfully accomplished without obvious psychological devastation and the goal of providing unbiased care led us to enroll these children in the BMT regimens on these studies.31,50Now, despite the small numbers of DS patients undergoing BMT, the results of CCG-2861 and CCG-2891 suggest that BMT adds toxicity without any apparent therapeutic gain in children with DS in AML in first remission. The results of CCG with standard timing induction therapy followed by chemotherapy, the results of POG 8498, and the use of low-dose ara-C alone in some children indicate that the majority of these children can be cured with regimens of moderate intensity.15,32,33 35

To explore the disease itself, we examined the obvious features that distinguish AML in the DS patients from AML in others: FAB M7 and an extra chromosome 21. Whereas megakaryoblastic morphology is prognostically neutral in the DS patients, it is significantly unfavorable in the others. FAB M7 encompasses heterogeneous diseases, some of which are responsive and others unresponsive. FAB M0 is also over-represented in the DS patients. Although generally regarded as an unfavorable form of AML because of its association with monosomy 7 and 7q-, FAB M0 is not unfavorable in those with DS.51 Interestingly, even monosomy 7 may not be unfavorable in those with DS.12 Morphology, immunophenotype, and karyotype in children with and without DS warrant further scrutiny.

An extra constitutional chromosome 21 clearly increases the risk of developing acute leukemia and, in the case of AML, clearly increases the chance of cure.15,18,30,35 Molecular mapping localizes DS to chromosome 21, band q22.1-22.2, the region ofAML1 gene involved in t(8;21), t(3;21), and t(16;21) AML, the familial platelet/AML disorder, the interferon α/β receptor, the cytokine receptor family, and other genes that regulate hematopoiesis, especially megakaryopoiesis.51-54We examined the effect of an extra chromosome 21 in the leukemic marrows of children with and without DS. An additional nonconstitutional chromosome 21 conferred no benefit in non-DS patients. In fact, in non-DS patients, there is a trend for the extra chromosome 21 in the leukemic population to confer a poorer outcome, whereas an extra nonconstitutional 21 in the DS patients appears to have no prognostic value.

The results of CCG-2861 and CCG-2891 show that AML and MDS in DS patients are characterized by demography, biology, and outcome that differ from that of other patients with AML. Current investigations are using less intensive therapy for AML in DS, defining the relationship between DS and the genes on chromosome 21, measuring differences in metabolism of chemotherapy, and examining apoptosis in the leukemia blasts of DS patients.

APPENDIX Participating Principal Investigators—Children's Cancer Group

| Institution . | Investigators . | Grant No. . |

|---|---|---|

| Group Operations Center Arcadia, CA | W. Archie Bleyer, MD Anita Khayat, PhD Harland Sather, PhD Mark Krailo, PhD Jonathan Buckley, MBBS, PhD Daniel Stram, PhD Richard Sposto, PhD | CA 13539 |

| University of Michigan Medical Center Ann Arbor, MI | Raymond Hutchinson, MD | CA 02971 |

| University of California Medical Center San Francisco, CA | Katherine Matthay, MD | CA 17829 |

| University of Wisconsin Hospital Madison, WI | Paul Gaynon, MD | CA 05436 |

| Children's Hospital & Medical Center Seattle, WA | Ronald Chard, MD | CA 10382 |

| Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital Cleveland, OH | Susan Shurin, MD | CA 20320 |

| Children's National Medical Center Washington, DC | Gregory Reaman, MD | CA 03888 |

| Children's Memorial Hospital Chicago, IL | Edward Baum, MD | CA 07431 |

| Children's Hospital of Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA | Jorge Ortega, MD | CA 02649 |

| Children's Hospital of Columbus Columbus, OH | Frederick Ruymann, MD | CA 03750 |

| Columbia Presbyterian College of Physicians & Surgeons New York, NY | Sergio Piomelli, MD | CA 03526 |

| Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh Pittsburgh, PA | Joseph Mirro, MD | CA 36015 |

| Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Nashville, TN | John Lukens, MD | CA 26270 |

| Doernbecher Memorial Hospital for Children Portland, OR | Lawrence Wolff, MD | CA 26044 |

| University of Minnesota Health Sciences Center Minneapolis, MN | William Woods, MD | CA 07306 |

| Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Philadelphia, PA | Anna Meadows, MD | CA 11796 |

| Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center New York, NY | Peter Steinherz, MD | CA 42764 |

| James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children Indianapolis, IN | Philip Breitfeld, MD | CA 13809 |

| University of Utah Medical Center Salt Lake City, UT | Richard O'Brien, MD | CA 10198 |

| University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada | Christopher Fryer, MD | CA 29013 |

| Children's Hospital Medical Center Cincinnati, OH | Robert Wells, MD | CA 26126 |

| Harbor/UCLA & Miller Children's Medical Center Torrance/Long Beach, CA | Jerry Finklestein, MD | CA 14560 |

| University of California Medical Center (UCLA) Los Angeles, CA | Stephen Feig, MD | CA 27678 |

| University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Iowa City, IA | Raymond Tannous, MD | CA 29314 |

| Childrens Hospital of Denver Denver, CO | Lorrie Odom, MD | CA 28851 |

| Mayo Clinic and Foundation Rochester, MN | Gerald Gilchrist, MD | CA 28882 |

| Izaak Walton Killam Hospital for Children Halifax, Canada | Dorothy Barnard, MD | — |

| University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC | Joseph Wiley, MD | — |

| University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey Camden, NJ | Milton Donaldson, MD | — |

| Children's Mercy Hospital Kansas City, MO | Maxine Hetherington, MD | — |

| University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE | Peter Coccia, MD | — |

| Wyler Children's Hospital Chicago, IL | F. Leonard Johnson, MD | — |

| M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Houston, TX | Beverly Raney, MD | — |

| Princess Margaret Hospital Perth, Western Australia | David Baker, MD | — |

| New York University Medical Center New York, NY | Aaron Rausen, MD | — |

| Children's Hospital of Orange County Orange, CA | Mitchell Cairo, MD | — |

| Institution . | Investigators . | Grant No. . |

|---|---|---|

| Group Operations Center Arcadia, CA | W. Archie Bleyer, MD Anita Khayat, PhD Harland Sather, PhD Mark Krailo, PhD Jonathan Buckley, MBBS, PhD Daniel Stram, PhD Richard Sposto, PhD | CA 13539 |

| University of Michigan Medical Center Ann Arbor, MI | Raymond Hutchinson, MD | CA 02971 |

| University of California Medical Center San Francisco, CA | Katherine Matthay, MD | CA 17829 |

| University of Wisconsin Hospital Madison, WI | Paul Gaynon, MD | CA 05436 |

| Children's Hospital & Medical Center Seattle, WA | Ronald Chard, MD | CA 10382 |

| Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital Cleveland, OH | Susan Shurin, MD | CA 20320 |

| Children's National Medical Center Washington, DC | Gregory Reaman, MD | CA 03888 |

| Children's Memorial Hospital Chicago, IL | Edward Baum, MD | CA 07431 |

| Children's Hospital of Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA | Jorge Ortega, MD | CA 02649 |

| Children's Hospital of Columbus Columbus, OH | Frederick Ruymann, MD | CA 03750 |

| Columbia Presbyterian College of Physicians & Surgeons New York, NY | Sergio Piomelli, MD | CA 03526 |

| Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh Pittsburgh, PA | Joseph Mirro, MD | CA 36015 |

| Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Nashville, TN | John Lukens, MD | CA 26270 |

| Doernbecher Memorial Hospital for Children Portland, OR | Lawrence Wolff, MD | CA 26044 |

| University of Minnesota Health Sciences Center Minneapolis, MN | William Woods, MD | CA 07306 |

| Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Philadelphia, PA | Anna Meadows, MD | CA 11796 |

| Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center New York, NY | Peter Steinherz, MD | CA 42764 |

| James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children Indianapolis, IN | Philip Breitfeld, MD | CA 13809 |

| University of Utah Medical Center Salt Lake City, UT | Richard O'Brien, MD | CA 10198 |

| University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada | Christopher Fryer, MD | CA 29013 |

| Children's Hospital Medical Center Cincinnati, OH | Robert Wells, MD | CA 26126 |

| Harbor/UCLA & Miller Children's Medical Center Torrance/Long Beach, CA | Jerry Finklestein, MD | CA 14560 |

| University of California Medical Center (UCLA) Los Angeles, CA | Stephen Feig, MD | CA 27678 |

| University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Iowa City, IA | Raymond Tannous, MD | CA 29314 |

| Childrens Hospital of Denver Denver, CO | Lorrie Odom, MD | CA 28851 |

| Mayo Clinic and Foundation Rochester, MN | Gerald Gilchrist, MD | CA 28882 |

| Izaak Walton Killam Hospital for Children Halifax, Canada | Dorothy Barnard, MD | — |

| University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC | Joseph Wiley, MD | — |

| University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey Camden, NJ | Milton Donaldson, MD | — |

| Children's Mercy Hospital Kansas City, MO | Maxine Hetherington, MD | — |

| University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE | Peter Coccia, MD | — |

| Wyler Children's Hospital Chicago, IL | F. Leonard Johnson, MD | — |

| M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Houston, TX | Beverly Raney, MD | — |

| Princess Margaret Hospital Perth, Western Australia | David Baker, MD | — |

| New York University Medical Center New York, NY | Aaron Rausen, MD | — |

| Children's Hospital of Orange County Orange, CA | Mitchell Cairo, MD | — |

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following cytogeneticists who contributed karyotypes to this study: T.W. Glover and S. Sheldon, University of Michigan; C. Sandin, Integrated Genetics; T.K. Mohandas, Harbor/UCLA Medical Center; C.W. Yu and L.L. Immken, Valley Children's Hospital; W.D. Loughman, Oakland Children's Hospital; R.S. Sparkes, UCLA Health Sciences Center; S.R. Patil, University of Iowa; L. McGavran, University of Colorado; V.M. Park, R. Stallard, and S. Schwartz, Case Western Reserve University; G.W. Dewald, Mayo Clinic; R. Gasparini, Baystate Medical Center; W.S. Stanley and S.A. Schonberg, Children's National Medical Center; K.W. Rao, University of North Carolina; K.-L. Ying, Children's Hospital Los Angeles; L.E. McMorrow and L.J. Sciorra, University of Medicine & Dentistry New Jersey; K.S. Theil, Ohio State University; L.M. Pasztor, Children's Mercy Hospital Kansas City; D. Warburton, Babies Hospital Columbia University; W.G. Sanger, University of Nebraska; S.L. Wenger, Children's Hospital Pittsburgh; S.M. Gollin, University of Pittsburgh; R.G. Best, University of South Carolina; M.G. Butler, Vanderbilt University; K.L. Satya-Prakash, Medical College of Georgia; M.M. LeBeau and D. Roulston, University of Chicago; R.E. Magenis, Oregon Health Sciences University; P.B. Jacky, Kaiser Permanente NW Regional Laboratory; D.C. Arthur, University of Minnesota; G. Williams and A.J. Dawson, Health Sciences Center of Winnipeg; P. Nowell, University of Pennsylvania; P.A. Farber, Geisinger Medical Center; S.C. Jhanwar, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; P.R.K. Koduru, North Shore University Hospital; P. Benn, University of Connecticut; N.A. Heerema, Indiana University; A.R. Brothman, University of Utah; D.K. Kalousek, British Columbia Children's Hospital; C. Phillips, Emory University; J.R. Waterson, Children's Hospital Medical Center Akron; D.E. Powell and A.L. Pettigrew, University of Kentucky.

Supported by Grants from the Division of Cancer Treatment, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD.

Contributing Children's Cancer Group Investigators, institutions, and grant numbers are given in the Appendix.

Address reprint requests to Beverly J. Lange, MD, Children's Cancer Group, PO Box 60012, Arcadia, CA 91066-6012.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal