Abstract

The development of a protective cellular immune response against human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is the most important determinant of recovery from HCMV infection after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT). The ultimate aim of our study is to develop an antigen-specific and peptide-based vaccine strategy against HCMV in the setting of BMT. Toward this end we have studied the cellular immune response against the immunodominant matrix protein pp65 of HCMV. Using an HLA A*0201-restricted T-cell clone reactive against pp65 from peripheral blood from a seropositive individual, we have mapped the position of the cytolytic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitope from HCMV pp65 to an 84-amino acid segment. Of the four peptides which best fit the HLA A*0201 motif in that region, one nonamer sensitized an autologous Epstein-Barr virus immortalized lymphocyte cell line for lysis. In vitro immunization of PBMC from HLA A*0201 and HCMV seropositive volunteers using the defined nonamer peptide stimulated significant recognition of HCMV infected or peptide-sensitized fibroblasts. Similarly, HLA A*0201 transgenic mice immunized with the nonamer peptide developed CTL that recognize both the immunizing peptide and endogenously processed pp65 in an HLA A*0201 restricted manner. Lipid modification of the amino terminus of the nonamer peptide resulted in its ability to stimulate immune respones without the use of adjuvant. This demonstration of a vaccine function of the nonamer peptide without adjuvant suggests its potential for use in an immunization trial of BMT donors to induce protective CTLs in patients undergoing allogeneic BMT.

HUMAN cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a member of the herpesvirus family of enveloped viruses and has been associated with a number of clinical syndromes. It has a genome of ∼230 kb of double-stranded DNA, which has been completely sequenced. The HCMV genome encodes more than 200 different polypeptides.1 HCMV infection is relatively common, and is usually self-limiting in the healthy, immunocompetent child or adult.2-4 Patients undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) are especially vulnerable to the morbidity resulting from HCMV.5 6 This is a result of the profound immunosuppression associated with treatment strategies aimed at preventing rejection or graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which also delay HCMV-specific immune reconstitution.

The HCMV life cycle provides insight into the most effective time frame for targeting a vaccine to maximally disrupt virus production and spread. pp65 and pp150, two viral structural matrix or tegument proteins, are produced during the late phase of gene expression7; however, mature pp65 protein is transferred into cells with the HCMV virion at the onset of infection, even before the initiation of viral gene expression.8,9 In fact, pp65 has been identified as a target antigen for HCMV-specific class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restricted cytolytic T lymphocyte (CTL) derived from the peripheral blood (PB) of most asymptomatic HCMV seropositive individuals.10,11 Importantly, CD8+ class I MHC restricted CTL specific for pp65 will recognize autologous HCMV-infected cells without the requirement for de novo viral gene expression.8,12,13 These observations led investigators to perform clinical trials in which donor-derived HCMV-specific CD8+ CTL were infused into BMT recipients as an alternative to ganciclovir prophylaxis and therapy.14 The transfer of CD8+ CTL clones to allogeneic BMT recipients results in the development of immunity to HCMV, and the reduction of cases of HCMV infection and pneumonia after BMT.15

MHC class I molecules preferentially bind to peptides that conform to a given sequence motif. The amino acid residues at specific positions of a peptide motif are conserved for a peptide to bind to MHC class I molecules with high affinity.16,17 In most cases the length of these peptides is between 8 and 11 amino acids as determined by either mass spectrometry or Edman degradation.18,19 Synthetic versions of these peptides bind to MHC molecules and sensitize targets to lysis by CD8+ CTL.18 Peptides that bind to MHC identified in this manner are referred to as “naturally processed epitopes” or minimal cytotoxic epitope (MCE). They require no further proteolytic processing to be active, and they are capable of sensitizing the TAP-deficient cell line, T2, for lysis by an appropriate MHC-restricted CTL.20

An alternative to an adoptive immunotherapy strategy, and analogous to the HBV (hepatitis B virus) vaccine,21 is to boost the memory response to HCMV using MCE peptides derived from the viral nucleoproteins pp65 or pp150. Toward this goal, we have defined an MCE from HCMV pp65. This epitope is recognized in five individuals that we have screened in the context of HLA A*0201, an allele which is expressed at a relatively high frequency in most ethnic populations.22 This MCE peptide can stimulate CD8+ CTL from asymptomatic and seropositive individuals to lyse HCMV-infected autologous fibroblasts in vitro. In addition, we have shown that in vivo immunization of HLA A2.1 transgenic mice with the MCE peptide will simulate an immune response which recognizes and kills HCMV-infected human fibroblasts. These studies suggest that the HLA A*0201 restricted peptide is a candidate CTL epitope vaccine to prevent or minimize HCMV infection after BMT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus stocks.Seed stock of HCMV isolate AD169 was provided by J. Zaia (City of Hope [COH] Medical Center). Concentrated virus stocks were prepared by standard methods which include infection of MRC-5 fibroblasts, harvesting of viral supernatant, and titreing of HCMV stocks on MRC-5 cells by immunoperoxidase detection of immediate-early and late antigens. Vaccinia viruses containing recombinant HCMV proteins were obtained from W. Britt (University of Alabama Medical Center, Birmingham), including full-length pp28 (Vac), pp65 (Vac), and pp150 (Vac). Wt strain WR of vaccinia virus was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD). Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected marmoset cells were obtained from S. Flanagan (COH).

Human serum.Plasma was obtained from anonymous donors who are blood group AB+ and HCMV seronegative as described.15 The HCMV status of the plasma was confirmed at the COH Clinical Microbiology Laboratory using a standard antibody test. Serum was prepared by the introduction of CaCl2 into the plasma transfer bag and the observation of clot formation. The soluble serum was extruded from the clot, clarified, heat inactivated at 55°C for 30 minutes, and tested for its ability to support normal human T-cell growth. A pool was made of four to five individual aliquots (150 to 200 mL), retested, and then frozen in aliquots to be thawed just before use in growth medium. The product is referred to as HAB.

Derivation of fibroblast cell lines.Three-millimeter skin punch biopsy samples were obtained from HLA-typed volunteers. A freshly excised biopsy specimen was immediately placed in 5 mL sterile complete medium (CM) (Waymouth's supplemented with L-Glutamine [Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD], Pen/Strep [Sigma, St Louis, MO], 15% heat inactivated fetal calf serum [FCS; Hyclone, Logan, UT], and 2.5 μg/mL Fungizone [Gemini Bioproducts]) in a 50-mL sterile culture tube. Skin and media were sterilely transferred to a 100-mm Petri dish and minced finely. Tissue pieces were distributed into a 12-well tissue culture plate. One milliliter of CM was added to each well, and the plate incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. When fibroblast outgrowth was apparent at 1 to 2 weeks, 0.5 to 1.0 mL CM was added, depending on the density of cells. One half of spent media was replaced as needed until cells were nearly confluent; each well was then trypsinized and cells passed to a T-25 flask and, after 1 to 2 weeks, to T-75 flasks. Aliquots were frozen in Waymouth's medium supplemented with 80% FCS, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a low passage number.

Derivation of EBV lymphocyte cell line (EBVLCL).EBV-treated PB mononuclear cells were used to derive transformed B-cell lines referred to as EBVLCL by standard methodology.23 Most cell lines were derived from volunteers at the COH. Some cell lines, including JY, are from a panel defined at the 11th International Workshop on Histocompatibility.24

Derivation of shuttle plasmids.Portions of pp65 cDNA were transferred from the polylinker region of the Bluescript (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) plasmids into the polylinker region of a modified pSC11 shuttle plasmid referred to as pSC11MCS25 (gift of R. Siliciano, Johns Hopkins Medical Center, Baltimore, MD). The shuttle plasmids were further modified by insertion of a 938-bp Sal I/Hpa I fragment of pEBVHis (Invitrogen) into the polylinker at the Sal I/Stu I sites which replaces all of the previous cloning sites with those from pEBVHis. Also inserted is a methionine codon with a Kozak translation initiation motif 26 flanked 3′ by restriction sites which change the reading frame by one base in each of the three different versions of pEBVHis (A, B, C). pp65 fragments in which the initiator methionine was removed were fused in frame using one of the three versions of pSC11MCS modified by EBVHis sequences (A, B, C). Plasmids were double banded in CsCl, and the correct reading frame was verified by dideoxy sequencing.

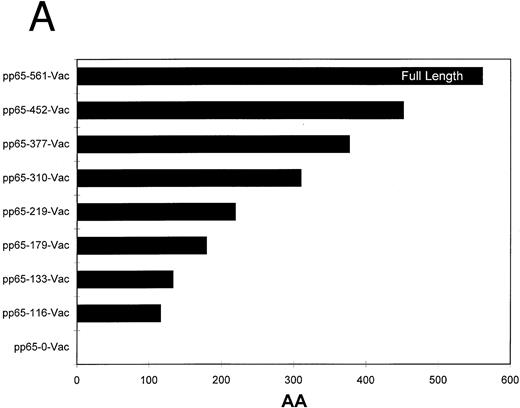

Homologous recombination and plaque purification of recombinant vaccinia viruses.The recombinant pSC11MCS plasmids were transfected into CV1 cells that had been simultaneously infected with an attenuated nonrecombinant laboratory strain of vaccinia virus (Strain WR) using Lipofectin (Life Sciences) as described.27 Homologous recombination will generate recombinant virus which was plaque purified several times using a combination of TK selection and β-galactosidase expression screening.28 The recombinant vaccinia was amplified by infection of progressively larger numbers of CV1 cells. The concentration of the final recombinant vaccinia virus was determined using a viral plaque assay. The deletion end points of the series of pp65 truncations used in this report are depicted in Fig 2a.

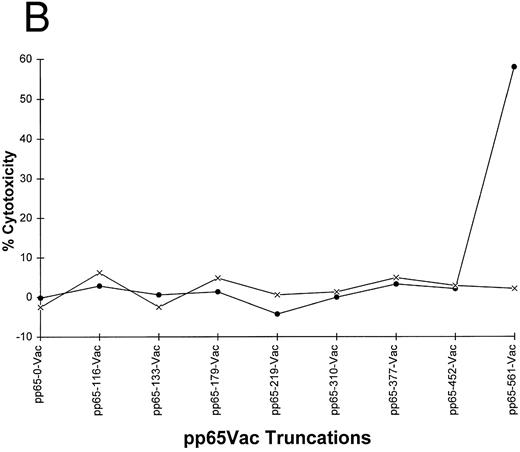

(A) Carboxyl terminal truncations of pp65 localize CTL epitope to a single region. Restriction fragments of pp65 were subcloned into pSC11MCS, and vaccinia viruses were made by techniques discussed in Materials and Methods. The size of the insert in “AA” is indicated by the length of the bars. (B) Identification of boundaries for location of CTL epitope. Either HLA A2 matched (•) or mismatched (×) EBVLCL targets were infected with the series of vaccinia viruses shown in (A). A standard CRA was performed using 10,000 targets at an E:T of 10.

(A) Carboxyl terminal truncations of pp65 localize CTL epitope to a single region. Restriction fragments of pp65 were subcloned into pSC11MCS, and vaccinia viruses were made by techniques discussed in Materials and Methods. The size of the insert in “AA” is indicated by the length of the bars. (B) Identification of boundaries for location of CTL epitope. Either HLA A2 matched (•) or mismatched (×) EBVLCL targets were infected with the series of vaccinia viruses shown in (A). A standard CRA was performed using 10,000 targets at an E:T of 10.

Derivation of CD8+CTL.Methods for deriving T-cell clones from HCMV seropositive individuals have been described in the literature.10 29 Our modified protocol is as follows: 40 to 50 mL of PB were obtained from HCMV seropositive volunteers (detected by standard antibody methods), and PB mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated from other blood components using Ficoll-HyPaque (DuPont) density gradient centrifugation. The cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and washed two times. Four to five million PBMCs/mL were resuspended in T-cell medium (TCM) with 10% HAB composed of RPMI-1640 (Irvine Scientific) together with 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 4 mmol/L L-glutamine, 25 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.5). To initiate the in vitro stimulation of the PBMCs, a monolayer of autologous dermal fibroblasts was established by plating the cells in 12-well plates at 105 cells/mL/well in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)-10% HAB for 24 hours. After 24 hours in culture the fibroblasts were infected with HCMV virions (AD169) for 2 hours at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of between 1 and 5. The medium was aspirated from the monolayer, and 1 mL of fresh DMEM-HAB was added. The monolayer was incubated in the medium for an additional 4 hours, after which time the medium was aspirated. Two milliliters of TCM-10% HAB containing 8 to 10 million PBMCs was added per well containing HCMV-infected fibroblasts.

The responder cells were restimulated on day 7 by plating onto a fresh monolayer of HCMV-infected autologous fibroblasts prepared as described above. In addition, γ-irradiated (2,500 rad) autologous PBMCs (fivefold over responder cells) were added as feeder cells, and the medium was supplemented with recombinant interleukin-2 (rIL-2, 10 IU/mL; Cetus) on days 2 and 4 of the second stimulation. Medium with rIL-2 was replaced as necessary in wells which exhibited rapid cell growth.

After 12 to 16 days in culture, the cells were harvested and assayed for recognition of HCMV matrix proteins in a chromium release assay (CRA). The CRA was performed by preparing antigen presenting cells (APCs) as target cells that were autologous or HLA-mismatched to the T-cell clone by infection with recombinant vaccinia viruses containing the DNA for HCMV proteins such as pp28Vac, pp65Vac, pp150Vac, or wild-type virus strain WR (wtVac). Fibroblasts used as targets in a CRA were first pretreated with 800 U/106 cells of recombinant interferon-γ (IFN-γ; Peprotech) for 48 hours to upregulate MHC class I expression.30 The fibroblasts were then infected with HCMV virions at an m.o.i. of between 1 and 5. After 2 hours, the medium was aspirated from the monolayer, and fresh DMEM-HAB was added for an additional 10 to 14 hours until the cells were harvested for chromium loading.

Targets were incubated with 100 μCi chromium-51 (ICN Pharmaceuticals) and the assay was performed as described.10 Briefly, after a 4-hour incubation period, the medium in which the cells were incubated was harvested. The release of radioactivity in the experimental condition (Re) was assessed with a gamma counter. The extent to which infected targets exhibit spontaneous lysis and the release of radioactivity (Rs) in the absence of CTLs was established for each virus vector. The maximum amount of radioactivity incorporated into and released by the target cells (Rmax) was established by lysis of target cells in a detergent (1% Triton X100; Sigma) solution. Percentage cytotoxicity can be expressed as: 100 × {(Re) − (Rs)}/{(Rmax) − (Rs)}.

PBMC stimulated two times by HCMV on infected dermal fibroblasts were cloned by limiting dilution in 96-well U-bottom plates. They were first depleted of CD4+ T cells by incubation with paramagnetic beads (Dynal) conjugated to anti-CD4 antibodies by negative selection. The resulting population was between 90% and 95% CD8+ and 99% CD3+ as assayed by either flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy (data not shown). This final population of cells was plated at a concentration of between 0.3 and 3 cells per well in a final volume of 150 μL. Each well also contained γ-irradiated 1.5 × 105 allogeneic PBMCs in TCM-10% FCS (HyClone) supplemented with 50 to 100 IU/mL rIL-2 (Cetus) and 0.5 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Murex). After 3 days of culture, the PHA was diluted twofold by exchanging 75 μL with fresh TCM-10% FCS supplemented with rIL-2 at the same concentration. The wells were supplemented with fresh rIL-2 every 3 to 4 days, and medium was replaced as necessary. The cells were restimulated after 12 to 14 days with irradiated fresh allogeneic PBMCs as described above, and the plates were carefully observed for growth in individual wells. At the stage of accumulation of several million cells, an aliquot was cryopreserved, and others were subjected to further screening.

Derivation of truncation plasmids in pCINEO.Portions of pp65 cDNA that are between the boundaries of the fragments contained in the series of vaccinia viruses as described previously were cloned into a modified pCINEO (Promega) vector. Similarly as for pSC11MCS, the polylinker region of pEBVHis as an Sal I/Not I fragment (775 bp) was transferred into the polylinker of pCINEO, and cloned into the Xho I/Not I site. pp65 fragments in which the initiator methionine was removed were fused in frame using one of the three versions of pCINEO modified by EBVHis sequences (A, B, C). Plasmids were double banded in CsCl, and the correct reading frame was verified by dideoxy sequencing.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) sensitivity assay.pp65 fragments along with the HLA A*0201 gene were cloned separately into pCINEO, and then transfected into COS cells. The pCINEO vector contains the SV40 ori region, which causes the plasmid DNA to replicate to high copy number in 2 days in COS cells, with concomitant high expression of gene products expressed from the plasmid.31 Methods for transfection can be found in the report of Buchwalder et al.32 Transfected COS cells were dislodged from individual wells of a 6-well plate using PBS/0.1 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8.0, and replated in 96-well U-bottom plates. Ten thousand COS cells were plated in triplicate wells for each experimental condition. 3-3F4 T cells (HLA A*0201 restricted pp65-specific T-cell clone, Fig 1c) were added to the COS cells at an effector:target (E:T) of 5. Control wells contained only 3-3F4 or COS cells. Cells were incubated for 24 hours in 200 μL TCM-10% FCS. After the incubation, the supernatant was manually harvested, and 50-μL aliquots from each well were deposited into three 96-well flat-bottom plates and frozen at −20°C until needed.

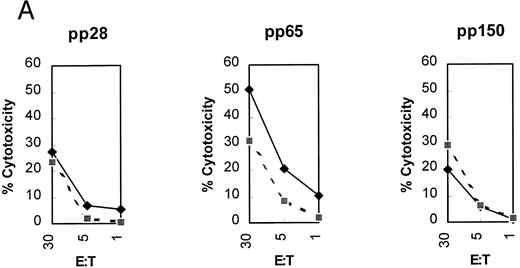

(A) Initial reactivity of polyclonal CD8+ T cells to HCMV nucleoproteins. After two rounds of stimulation on HCMV-infected autologous fibroblasts, PBMCs were depleted of CD4+ T cells. The population of PBMCs before depletion was tested in a CRA for recognition against autologous (diamonds) or mismatched (squares) EBVLCL targets infected with vaccinia viruses for 16 hours expressing the HCMV proteins written above each panel. Methods for conducting the experiments can be found in Materials and Methods. Spontaneous lysis did not exceed 30% for any of the vaccinia cell lines tested. Ten thousand targets were assayed for each condition at the E:T indicated. (B) Recognition of HCMV nucleoproteins by clonal CD8+ CTL. CD4+ depleted PBMCs were cloned in 96-well plates as described in Materials and Methods. Wells were restimulated every 14 days. Colonies visible to the eye were expanded in successively larger wells, and aliquots of cells were tested against the recombinant vaccinia viruses containing HCMV proteins pp28, pp65, and pp150.11 Conditions for the CRA can be found in Materials and Methods and the legend for (a). Six representative CD8+ T-cell clones, 1G6, 3F6, 1H2, 3G2, 2H3, and 3-3F4, were tested at two different E:Ts against autologous and mismatched EBVLCL targets infected with the vaccinia viruses indicated at the bottom of the figure. Data from the E:T = 10 series are shown.

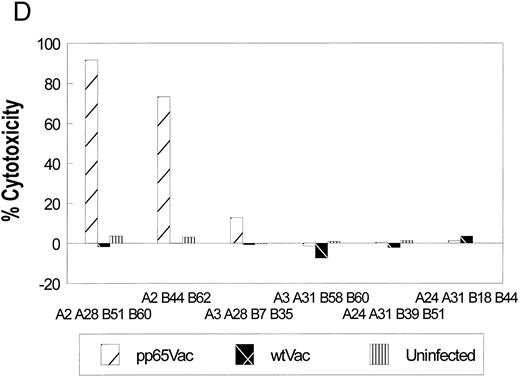

(C) Specific recognition of HCMV-infected fibroblasts by CD8+ CTL clone 3-3F4. Autologous (▨) and mismatched () fibroblasts were treated with IFN-γ for 2 days before infection with the AD169 strain of HCMV as described in Materials and Methods. Mock-infected fibroblasts were treated with medium alone. Two thousand fibroblasts were incubated with 3-3F4 T cells at an E:T of 10 in a standard 4-hour CRA. (D) MHC restriction of the 3-3F4 T-cell clone response to HCMV pp65. EBVLCL targets from individuals HLA-typed at the COH were infected with vaccinia viruses with (pp65Vac) or without (wtVac) recombinant HCMV pp65, or mock-infected. A standard CRA was performed using 10,000 targets at an E:T of 10. Cell lines expressing single allele matches from the autologous EBVLCL (A2 A28 B51 B60) were tested for recognition by the T-cell clone 3-3F4, as well as a completely matched (autologous) and mismatched EBVLCL targets.

(E) T-cell clone 3-3F4 recognizes HCMV pp65 with HLA A*0201. EBVLCL JY (▨) or Jurkat cells transfected with the HLA A*0201 genomic DNA clone (), or the untransfected parental Jurkat cells (▥) were tested for recognition by T-cell clone 3-3F4 in a standard CRA using 10,000 targets at an E:T of 10.

(A) Initial reactivity of polyclonal CD8+ T cells to HCMV nucleoproteins. After two rounds of stimulation on HCMV-infected autologous fibroblasts, PBMCs were depleted of CD4+ T cells. The population of PBMCs before depletion was tested in a CRA for recognition against autologous (diamonds) or mismatched (squares) EBVLCL targets infected with vaccinia viruses for 16 hours expressing the HCMV proteins written above each panel. Methods for conducting the experiments can be found in Materials and Methods. Spontaneous lysis did not exceed 30% for any of the vaccinia cell lines tested. Ten thousand targets were assayed for each condition at the E:T indicated. (B) Recognition of HCMV nucleoproteins by clonal CD8+ CTL. CD4+ depleted PBMCs were cloned in 96-well plates as described in Materials and Methods. Wells were restimulated every 14 days. Colonies visible to the eye were expanded in successively larger wells, and aliquots of cells were tested against the recombinant vaccinia viruses containing HCMV proteins pp28, pp65, and pp150.11 Conditions for the CRA can be found in Materials and Methods and the legend for (a). Six representative CD8+ T-cell clones, 1G6, 3F6, 1H2, 3G2, 2H3, and 3-3F4, were tested at two different E:Ts against autologous and mismatched EBVLCL targets infected with the vaccinia viruses indicated at the bottom of the figure. Data from the E:T = 10 series are shown.

(C) Specific recognition of HCMV-infected fibroblasts by CD8+ CTL clone 3-3F4. Autologous (▨) and mismatched () fibroblasts were treated with IFN-γ for 2 days before infection with the AD169 strain of HCMV as described in Materials and Methods. Mock-infected fibroblasts were treated with medium alone. Two thousand fibroblasts were incubated with 3-3F4 T cells at an E:T of 10 in a standard 4-hour CRA. (D) MHC restriction of the 3-3F4 T-cell clone response to HCMV pp65. EBVLCL targets from individuals HLA-typed at the COH were infected with vaccinia viruses with (pp65Vac) or without (wtVac) recombinant HCMV pp65, or mock-infected. A standard CRA was performed using 10,000 targets at an E:T of 10. Cell lines expressing single allele matches from the autologous EBVLCL (A2 A28 B51 B60) were tested for recognition by the T-cell clone 3-3F4, as well as a completely matched (autologous) and mismatched EBVLCL targets.

(E) T-cell clone 3-3F4 recognizes HCMV pp65 with HLA A*0201. EBVLCL JY (▨) or Jurkat cells transfected with the HLA A*0201 genomic DNA clone (), or the untransfected parental Jurkat cells (▥) were tested for recognition by T-cell clone 3-3F4 in a standard CRA using 10,000 targets at an E:T of 10.

Measurement of TNF-α using the WEHI-164 cell line (kind gift of N. Ruddle, Yale University, New Haven, CT) bio-assay was performed as previously described.33 34 The assay detects the amount of TNF-α by its ability to inhibit cell proliferation. The actual quantity of TNF-α was measured indirectly using the water-soluble MTS assay (CellTiter 96; Promega Corp, Madison, WI) with known amounts of the cytokine as standards. Absorbance was read at 490 nm using a plate reader (ThermoMax, Molecular Devices), and a standard curve of TNF-α concentration was generated using proprietary software (SoftMax Pro, Molecular Devices). Experimental values were generated by the use of the software, and were acceptable if the mean of three determinations had a variance less than 30%.

Peptide synthesis.Peptides were synthesized on an ABI 432 using Fmoc chemistry as a 25 μmol/L synthesis. Peptides were cleaved from the resin using standard TFA/thioanisole/ethanedithiol cleavage mixtures, allowing increased times for removal of protecting groups from arginines.35 Lipidated peptides were similarly synthesized, except that 75 μmol of the lipid, palmitic acid (Aldrich) was added as the final coupling to the peptide during the automated synthesis protocol. For monolipidated peptide, a standard Fmoc-L-Lysine (Boc) protected amino acid cartridge was used in a single coupling step (see Table 3). Dilipidated peptides were synthesized by two additions of palmitic acid to the Fmoc-L-Lysine-Fmoc protected amino acid (Bachem). Lyophilized peptides were dissolved in either 0.1% acetic acid or 10% DMSO in H2O, depending on hydrophobicity at a concentration of 5 mg/mL. Peptides were analytically chromatographed on a Vydac (Hesperia, CA) C18 column in 0.1% TFA and developed with a gradient of acetonitrile from 0% to 60%. Peptides used in this study have purities of ≥80%, and were evaluated by either Fast Atom Bombardment (FAB) mass spectrometry or amino acid analysis, or both.

Primary Structure of Peptides Used to Immunize HLA A2.1 Transgenic Mice

| Lipid Molecule(s) . | Adaptor Sequence . | Epitope Sequence . | Carboxyl Terminus . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -K-S-S- | -N-L-V-P-M-V-A-T-V- | OH |

| 1 Palmitic acid | -K-S-S- | -N-L-V-P-M-V-A-T-V- | OH |

| 2 Palmitic acid | -K-S-S- | -N-L-V-P-M-V-A-T-V- | OH |

| Lipid Molecule(s) . | Adaptor Sequence . | Epitope Sequence . | Carboxyl Terminus . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -K-S-S- | -N-L-V-P-M-V-A-T-V- | OH |

| 1 Palmitic acid | -K-S-S- | -N-L-V-P-M-V-A-T-V- | OH |

| 2 Palmitic acid | -K-S-S- | -N-L-V-P-M-V-A-T-V- | OH |

Peptides were synthesized on the ABI 432 (Applied Biosystems) and purified and analyzed as described in the legend to Table 1. Palmitic acid (Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethylformamide, and automatically coupled to the amino terminal lysine. The amino terminal lysine of the monolipidated form of the peptide was protected by two protecting groups, Fmoc and Boc. Only the Fmoc is cleaved during synthesis to allow for a single lipid moiety to be added. For the dilipidated form, a double Fmoc protected form of lysine was used, therefore allowing for two lipid moieties to be added. Refer to Materials and Methods for further details of the synthesis of lipidated peptides.

Peptide screening and CTL sensitivity.Peptides to be screened were diluted to 10 μmol/L in TCM and incubated with chromated targets for 1 hour before washing two times with TCM. Peptide-loaded targets were incubated with T-cell clone 3-3F4 for 4 hours in a 37°C CO2 incubator at varying E:T ratios, then the supernatants were harvested and counted in a Cobra II Gamma Counter (Packard Instrument).

Determination of CTL sensitivity to peptide concentration was conducted using either autologous EBVLCL or T2 cells.20 Peptides were serially diluted from a 10 μmol/L stock solution, incubated with chromated targets for 1 hour, before washing two times with TCM. A CRA was performed as described above.

In vitro immunization of human PBMCs.Several different procedures were used, although our modification of a protocol developed recently for in vitro immunization with CTL epitopes works most efficiently and reproducibly.36 For data shown in Fig 4a, a different approach was used. Monolayers of HLA A*0201 fibroblasts were incubated with CTL epitope at 10 μmol/L for 2 hours, then the peptide washed out. Fresh PBMCs were added to the monolayer and incubated for 7 days in TCM-10% HAB medium. The responder cells from the first stimulation were depleted of CD4+ T cells by negative selection using Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway), then transferred to a second peptide-sensitized fibroblast monolayer for a second week. rIL2 at 10 IU/mL was added on days of stimulation, some of the PBMCs were tested in a CRA against autologous fibroblasts, either peptide sensitized, HCMV-infected, or untreated at an E:T = 25. Fibroblasts were pretreated with 800 U/106 cells of IFN-γ (Peprotech) for 48 hours as described above. The remaining responder cells were transferred to fresh peptide-sensitized fibroblasts for a third stimulation. A final CRA was done during week 4. The experiment shown in Fig 4b was done according to Wentworth et al.36 A slight modification of the technique consisted of using acid-stripped and peptide-loaded PHA blasts as stimulators for both stimulations.36

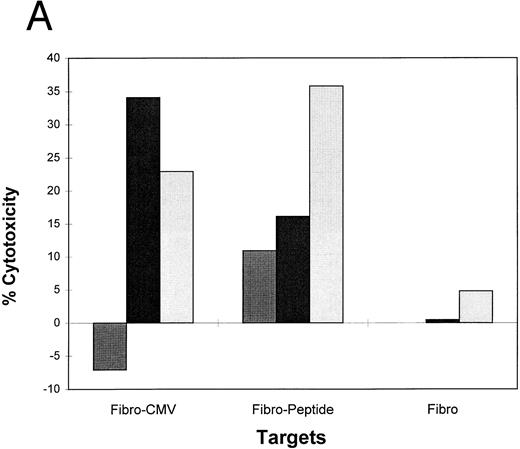

(A) PBMCs from a seropositive donor are inducible to become HCMV-specific cytotoxic effectors using peptide-loaded fibroblasts. Autologous fibroblasts were incubated with 10 μmol/L pp65495-503 , and fresh PBMCs were added to the well for a 7-day stimulation repeated three times as described in Materials and Methods. Two days before harvest of the PBMCs, autologous fibroblasts were treated with IFN-γ, and infected with HCMV strain AD169. Additional IFN-γ–treated fibroblasts were incubated with peptide or medium, and a CRA was conducted at the indicated time points using 2,000 targets in each case. To verify that the target fibroblasts could function as APC, at each time point they were evaluated against the T-cell clone 3-3F4 (data not shown). The CRAs were conducted at each time point using PBMCs that had been depleted of CD4+ T cells. (), Day 0; (▪), second stimulation; (), third stimulation. (B) PBMCs from a seropositive donor are inducible to become HCMV-specific cytotoxic effectors using peptide-loaded PHA-blasts. Fresh PBMCs were incubated with peptide-loaded PHA-blasts for two rounds of stimulation. The effectors were incubated with CMV-infected or peptide-sensitized fibroblasts as described in (A). Both autologous and completely HLA mismatched fibroblast targets were used in CRAs with the peptide-stimulated PBMCs. (), Matched; (▪), mismatched.

(A) PBMCs from a seropositive donor are inducible to become HCMV-specific cytotoxic effectors using peptide-loaded fibroblasts. Autologous fibroblasts were incubated with 10 μmol/L pp65495-503 , and fresh PBMCs were added to the well for a 7-day stimulation repeated three times as described in Materials and Methods. Two days before harvest of the PBMCs, autologous fibroblasts were treated with IFN-γ, and infected with HCMV strain AD169. Additional IFN-γ–treated fibroblasts were incubated with peptide or medium, and a CRA was conducted at the indicated time points using 2,000 targets in each case. To verify that the target fibroblasts could function as APC, at each time point they were evaluated against the T-cell clone 3-3F4 (data not shown). The CRAs were conducted at each time point using PBMCs that had been depleted of CD4+ T cells. (), Day 0; (▪), second stimulation; (), third stimulation. (B) PBMCs from a seropositive donor are inducible to become HCMV-specific cytotoxic effectors using peptide-loaded PHA-blasts. Fresh PBMCs were incubated with peptide-loaded PHA-blasts for two rounds of stimulation. The effectors were incubated with CMV-infected or peptide-sensitized fibroblasts as described in (A). Both autologous and completely HLA mismatched fibroblast targets were used in CRAs with the peptide-stimulated PBMCs. (), Matched; (▪), mismatched.

Murine immunizations.C57 BL/6 mice transgenic for the human HLA A*0201 gene37 (kind gift of V. Engelhard, University of Virginia, Charlottesville) were immunized with peptides from pp65 (aa 495-503, see Table 2) or from human p53 (aa 149-15730) by a modification of previously published protocols.21,30,38,39 Briefly, 100 μg of CTL epitope and 20 μg of PADRE HTL (T-helper) epitope38 were diluted into PBS from 5-mmol/L stocks. This was mixed with incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA), and emulsified by sonication for 15 to 30 seconds. Each mouse received 100 μL of peptide/IFA by subcutaneous injection at the base of the tail. There was no booster, and after 12 to 14 days the mice were killed and the spleens removed.

HLA A*0201 Motif Peptides Between 477-561 AA of HCMV pp65

| Amino Acid Sequence of Peptide . | Amino Acid No. . | Motif . | Score* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| I L A R N L V P M V | 491-500 | A*0201-decamer | 67 |

| E L E G V W Q P A | 526-534 | A*0201-nonamer | 59 |

| R I F A E L E G V | 522-530 | A*0201-nonamer | 55 |

| N L V P M V A T V | 495-503 | A*0201-nonamer | 63 |

| Amino Acid Sequence of Peptide . | Amino Acid No. . | Motif . | Score* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| I L A R N L V P M V | 491-500 | A*0201-decamer | 67 |

| E L E G V W Q P A | 526-534 | A*0201-nonamer | 59 |

| R I F A E L E G V | 522-530 | A*0201-nonamer | 55 |

| N L V P M V A T V | 495-503 | A*0201-nonamer | 63 |

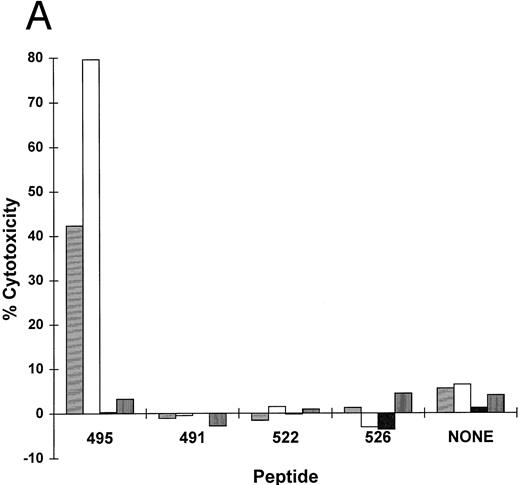

Vaccinia truncation analysis (Fig 2) established a limited region between 477-561 where the epitope lies. Computer analysis of the sequence of HCMV pp65 shows 4 relatively high scoring peptides in that region, which generally reflects good binding to the MHC.51 Each peptide was synthesized on the ABI 432 peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems), and tested for recognition by 3-3F4 (see Fig 3). Note that peptides at pp65491-500 and pp65495-503 overlap.

Adapted from D'Amaro et al.51

A splenic suspension was made, and the effectors were added to spleen-cell APCs from a littermate which were first lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated for 72 hours,39 then acid treated and peptide loaded according to a modification40 of Wentworth et al.36 An additional in vitro stimulation was performed on day 7 using acid-treated and peptide-pulsed Jurkat/A2.1 cells.40 Six days after the second in vitro stimulation, a CRA was performed to test the cytotoxic activity of the responding cells against relevant and irrelevant peptide-pulsed targets. For establishing long-term CTL lines, the responding cells were restimulated at weekly intervals with acid-treated and peptide-pulsed Jurkat/A2.1 cells as APC and irradiated spleen cells as feeders. Beginning with the third week of in vitro stimulation, growth factors in the form of 5% (vol/vol) Rat T-Stim with Con A (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) were added to the culture.

RESULTS

Derivation of T-cell clones.Previous work has established that pp65 is a common target protein of a CD8+ CTL response against HCMV in seropositive individuals.10,13,41 Because HLA A*0201 is the most commonly expressed polymorphic class I HLA allele in North America,42 and pp65 is the preferred CTL target from HCMV in most individuals, we hypothesized that recognition of pp65 might be HLA A*0201 restricted. We used methodology to derive CD8+ clones from HLA A*0201 typed individuals that is similar in concept to published protocols.10 15 We confirmed that two stimulations on HCMV-infected fibroblasts were effective in increasing the precursor frequency of HCMV pp65 specific T cells by conducting a 51Cr release assay (CRA) with appropriate controls using EBVLCL targets that had been previously infected with pp65Vac (Fig 1A). Minimal responses were detected against pp28Vac and pp150Vac, whereas the greatest response was found against pp65Vac. The specific polyclonal responses against pp65 prompted us to CD4+ deplete and clone CD8+ CTL by limiting dilution, to further characterize the specific allelic restriction and epitope specificity. After two stimulations (see Materials and Methods), we obtained numerous clones, 21 of which were expanded and tested.

Determination of antigen specificity and MHC restriction.Representative clones were tested in a CRA against HCMV proteins expressed from vaccinia viruses including pp28, pp65, pp150, and wtVac as a control (Fig 1B). Targets were either the autologous EBVLCL, or EBVLCL mismatched at the HLA A and B loci. Of the 21 clones, only one had significant reactivity against autologous EBVLCL targets infected with pp65Vac with minimal reactivity against an HLA-mismatched line. The clone, designated 3-3F4, also showed minimal reactivity against pp28Vac (data not shown), pp150Vac, and wtVac infected EBVLCL targets. The T-cell clone also recognized and killed HCMV-infected autologous fibroblasts in an MHC-restricted manner (Fig 1C). We also identified the HLA A*0201 allele as the restriction element for the recognition of pp65 (Fig 1D). To ensure that the restricting allele was HLA A*0201 and not a subtype allele,43 we conducted a CRA using HLA A*0201 transfected Jurkat cells and HLA A*0201 expressing JY cells as targets. Once again, the HLA A*0201 allele was necessary and sufficient as the MHC restricting allele for the T-cell clone 3-3F4 (Fig 1E).

Definition of the minimal cytotoxic epitope.A proven approach for locating the proximity of a CTL epitope is to use truncations of the target protein expressed as vaccinia viruses.44,45 We created a series of carboxyl terminal deletions of pp65, and cloned them into vaccinia virus strain WR using homologous recombination with a modified pSC11 shuttle vector46 (Fig 2A). Among the series tested, the vaccinia vector that encodes the whole pp65 protein was the only one that sensitized HLA A*0201 EBVLCL targets for lysis (Fig 2B). This analysis localized the CTL epitope between aa 452-561 (the carboxyl terminus of the protein). As expected, a mismatched EBVLCL target infected with the same vector was not recognized by 3-3F4 (Fig 2B).

Further narrowing of the region containing the epitope was accomplished by using the COS cell transfection system,47 and quantitative analysis of cytokine release by T-cell clone 3-3F4 using the WEHI 164 cell assay.33,48 A plasmid containing the human HLA A*0201 gene49 was cotransfected into COS cells with portions of the pp65 gene, with each separately cloned into an expression vector and fused in frame with a Kozak consensus sequence. Although COS cells are relatively resistant to direct lysis by human CD8+ CTL, when appropriately recognized they are capable of stimulating the T cells to produce cytokines such as TNF-α in a 24-hour incubation.50 When this assay was applied to monitor whether 3-3F4 produced TNF-α in response to PMA/PHA stimulation, a highly positive response was measured (Table 1). A series of plasmids was then constructed to further narrow the region where the putative HLA A*0201 epitope is located (Table 1). Plasmids which have an amino terminus at aa 452 or 477 worked as well as full-length pp65, whereas a fragment between aa 376-452 was not recognized, and no TNF-α was produced. Therefore, the region with the epitope was further narrowed to 84 aa between 477-561.

T-Cell Clone 3-3F4 Makes TNF-α in Response to an 84 AA Fragment of pp65 Expressed in COS Cells With HLA A*0201

| Condition . | pp65 AA Tested . | HLA A*0201 . | pg TNF-α Detected . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-3F4 | None | No | ND |

| 3-3F4 + PMA/PHA | None | No | 27.9 |

| 3-3F4 + COS | 1-561 | Yes | 32.3 |

| 3-3F4 + COS | 377-452 | Yes | ND |

| 3-3F4 + COS | 452-561 | Yes | 21.2 |

| 3-3F4 + COS | 477-561 | Yes | 33.0 |

| 3-3F4 + COS | None | Yes | ND |

| 3-3F4 + COS | None | No | ND |

| COS | 1-561 | Yes | ND |

| COS | 452-561 | Yes | ND |

| COS | 377-452 | Yes | ND |

| COS | 477-561 | Yes | ND |

| COS | None | Yes | ND |

| Condition . | pp65 AA Tested . | HLA A*0201 . | pg TNF-α Detected . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-3F4 | None | No | ND |

| 3-3F4 + PMA/PHA | None | No | 27.9 |

| 3-3F4 + COS | 1-561 | Yes | 32.3 |

| 3-3F4 + COS | 377-452 | Yes | ND |

| 3-3F4 + COS | 452-561 | Yes | 21.2 |

| 3-3F4 + COS | 477-561 | Yes | 33.0 |

| 3-3F4 + COS | None | Yes | ND |

| 3-3F4 + COS | None | No | ND |

| COS | 1-561 | Yes | ND |

| COS | 452-561 | Yes | ND |

| COS | 377-452 | Yes | ND |

| COS | 477-561 | Yes | ND |

| COS | None | Yes | ND |

Fragments of pp65 were cloned in frame after a Kozak Initiation sequence in a modified version of pCINEO (see Materials and Methods). HLA A*0201 was also cloned as a genomic fragment in pCINEO. COS cells were transfected with and without HLA A*0201, and with fragments of pp65 in pCINEO as described in Materials and Methods. Ten thousand COS cells per well were incubated for 24 hours in a 96-well plate in triplicate with or without T-cell clone 3-3F4 at an E:T of 5. As controls, 3-3F4 T cells with and without PMA/PHA stimulation were also incubated in triplicate in a 96-well plate without COS cells. 50 μL of supernatant was introduced into wells containing the TNF-α sensitive WEHI-164 cells in triplicate for a 48-hour incubation.

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

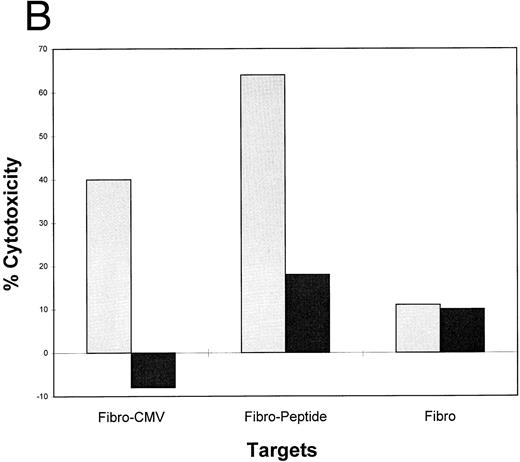

The sequence of pp65 was scanned for HLA A*0201 binding motif peptides using a computer algorithm developed for that purpose.51 A series of peptides with progressively better fit to an optimal binding motif were predicted. Shown in Table 2 are four of the peptides with the best scores from the region 477-561: three are nonamers and one is a decamer that overlaps the nonamer at position 495. These four peptides at 10 μmol/L were incubated with an HLA A*0201 EBVLCL targets to determine if they would cause them to become sensitive to lysis in a CRA with T-cell clone 3-3F4. One nonamer peptide, at aa 495-503, sensitized target cells for lysis as efficiently as infection with pp65Vac (Fig 2B). No activity on HLA mismatched cells was observed (Fig 3A). We titered the peptide to establish how well it bound to HLA A*0201 using an EBVLCL and the transporter associated with T-cell antigen processing (TAP) transporter-deficient cell line, T2,20 as targets (Fig 3B). The peptide gave maximal lysis at 0.66 nmol/L on an HLA A*0201 TAP+ cell, and 0.02 nmol/L on T2 cells, at an E:T of 5. These numbers compare favorably with other HLA A*0201 binding CTL epitopes.52-55

(A) HLA A*0201 nonamer motif peptide primes matched EBVLCL targets to be lysed by T-cell clone 3-3F4. HLA A*0201 peptides (Table 2) in the region 477-561 AA from HCMV pp65 were synthesized.51,55 62 Matched and mismatched EBVLCL targets were incubated with 10 μmol/L of each peptide or no peptide (none) while 51Cr loading for 1 hour, the peptide was washed out, and 10,000 of each target was incubated with T-cell clone 3-3F4 at the indicated E:T in a standard CRA. (▤), Matched E:T = 1; (□), matched E:T = 5; (▪), mismatch E:T = 1; (▥), mismatch E:T = 5. (B) Sensitivity of CTL killing to peptide concentration: Comparison of TAP+ and TAP− cell lines. T2 (TAP−) or JY (TAP+) cells were incubated with serial dilutions of pp65495-503 at the indicated concentration for 1 hour at 37°C. The peptide was washed out and a standard CRA was performed using 10,000 targets at the E:Ts shown. (♦), TAP+, E:T = 1; (▪), TAP+, E:T = 5; (), TAP−, E:T = 1; (×), TAP−, E:T = 5.

(A) HLA A*0201 nonamer motif peptide primes matched EBVLCL targets to be lysed by T-cell clone 3-3F4. HLA A*0201 peptides (Table 2) in the region 477-561 AA from HCMV pp65 were synthesized.51,55 62 Matched and mismatched EBVLCL targets were incubated with 10 μmol/L of each peptide or no peptide (none) while 51Cr loading for 1 hour, the peptide was washed out, and 10,000 of each target was incubated with T-cell clone 3-3F4 at the indicated E:T in a standard CRA. (▤), Matched E:T = 1; (□), matched E:T = 5; (▪), mismatch E:T = 1; (▥), mismatch E:T = 5. (B) Sensitivity of CTL killing to peptide concentration: Comparison of TAP+ and TAP− cell lines. T2 (TAP−) or JY (TAP+) cells were incubated with serial dilutions of pp65495-503 at the indicated concentration for 1 hour at 37°C. The peptide was washed out and a standard CRA was performed using 10,000 targets at the E:Ts shown. (♦), TAP+, E:T = 1; (▪), TAP+, E:T = 5; (), TAP−, E:T = 1; (×), TAP−, E:T = 5.

Response to pp65495-503 peptide by serologic HLA A2 individuals.We wanted to confirm whether the pp65495-503 peptide could sensitize fibroblasts, a physiologic target of HCMV infection to be killed by the T-cell clone 3-3F4. Dermal fibroblasts from three serologically HLA A2 defined individuals were treated with IFN-γ for 48 hours, then infected with HCMV for 18 hours, or incubated with the pp65495-503 peptide for 2 hours, and a CRA was performed. The peptide or HCMV infection both caused target lysis, while uninfected fibroblasts were not recognized by the T-cell clone, 3-3F4 (data not shown). This result indicates that the peptide could serve as an effective vaccine, if it is capable of eliciting CTL after immunization of individuals who are HCMV seropositive.

In vitro immunization studies.We wanted to establish the conditions for in vitro immunization using the pp65495-503 peptide as a means to predict whether it might be active in vivo. We stimulated PBMCs from two HCMV seropositive individuals using two different approaches. The stimulator cells were either peptide loaded autologous fibroblasts (Fig 4A) or PHA blasts (Fig 4B) that were first acid treated then peptide pulsed.56 After two or three rounds of peptide stimulation, the PBMC effector population was assayed in a CRA for recognition of either HCMV-infected, peptide-loaded, or untreated autologous fibroblasts (Fig 4A and B). In one case we were able to compare the level of target killing before and after peptide stimulation (Fig 4A). It is evident that the peptide caused recognition of HCMV-infected fibroblasts by the effector population, and in one case we show that the recognition is MHC-restricted (Fig 4B). We have recently derived HLA A*0201-restricted and pp65-specific CTL which recognize pp65495-503 from two additional volunteers using the methods described here, and in vitro restimulation using pp65Vac57 (unpublished results, April 1997). Therefore, we have identified a total of five asymptomatic HCMV seropositive HLA A*0201 individuals who use peptide pp65495-503 in their immune response against HCMV.

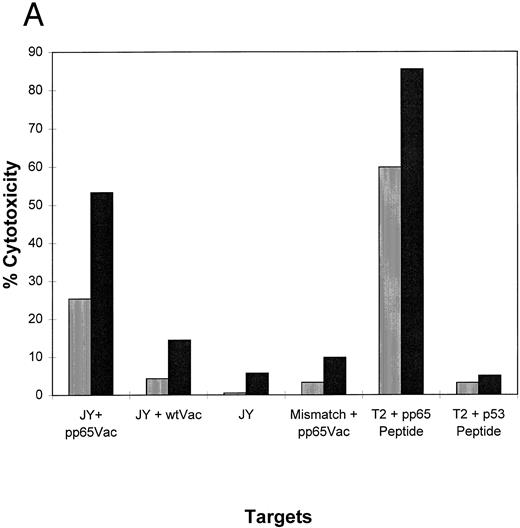

Immunization of a transgenic mouse model of HLA A*0201.The results from our in vitro stimulation of PBMC suggest that the pp65495-503 peptide may function in vivo to stimulate CTL precursor (CTLp) as a memory response from individuals with prior HCMV exposure. To test whether the peptide could stimulate de novo CTLp without prior virus exposure, we turned to a transgenic mouse model, the HLA A*0201 mouse.37 Three mice were immunized subcutaneously at the base of the tail with peptide pp65495-503 from pp65 or peptide p53149-157 from p5330 together with the polyclonal HTL peptide PADRE38 emulsified in IFA. After 12 days a splenic suspension was made, and the effector cells were restimulated using p53149-157 or pp65495-503 peptide sensitized syngeneic LPS blasts.58 Thereafter, the stimulator cells were Jurkat A2.1 cells, prepared by acid treatment and subsequent loading of peptides. After two in vitro restimulation cycles, the splenic effector population was tested for recognition of p53149-157 or pp65495-503 peptide-loaded T2 cells. There was clear evidence of recognition of pp65495-503 or p53149-157 peptide in mice that had been appropriately immunized, without recognition of the nonimmunizing peptide (data not shown). We then tested whether the splenic effectors would recognize endogenously processed pp65 in a CRA with human HLA A*0201 EBVLCL targets infected with pp65Vac (Fig 5A). The results clearly show that the splenic effector population from the pp65495-503 immunization are recognizing endogenously processed pp65 in an HLA A*0201–restricted manner. Further proof that pp65495-503 peptide causes recognition of virus-infected cells comes from a CRA using HCMV-infected human fibroblasts as targets, and murine CTL derived from the pp65495-503 peptide stimulation as the effector population. HLA A*0201 fibroblasts infected with HCMV were lysed by the CTL, whereas both uninfected or mismatched fibroblasts were not recognized (Fig 5B).

(A) HLA A2.1 transgenic mice recognize pp65495-503 and develop CTL that lyse EBVLCL targets which express endogenously processed HCMV pp65. Mice were immunized once with pp65495-503 as described in the text and Materials and Methods. After five in vitro stimulations, the CTL were tested against uninfected JY cells, or infected with pp65 (pp65Vac) or wt (wtVac) vaccinia viruses. A non-HLA A2.1 EBVLCL was included as a control. The specificity of the CTL for pp65495-503 peptide was shown in an assay using peptide-loaded T2 cells using either the pp65 or a p53 HLA A2 epitope. A standard CRA was performed using 5,000 targets at an E:T of 2 (▥) and 20 (▪). (B) HCMV-infected fibroblasts are lysed by immunized splenic effectors. MRC-5 which expresses HLA A*0201 and non-HLA A*0201 fibroblasts were infected for 16 hours with HCMV strain AD169. The infected and noninfected fibroblasts were chromated, and 2,000 were used as targets for each point in a standard CRA using peptide-stimulated murine splenic effectors as in (A). Simultaneously, the recognition of peptide-loaded and nonloaded T2 cells was evaluated using the same effector population. (▥), E:T = 2; (▪), E:T = 20.

(A) HLA A2.1 transgenic mice recognize pp65495-503 and develop CTL that lyse EBVLCL targets which express endogenously processed HCMV pp65. Mice were immunized once with pp65495-503 as described in the text and Materials and Methods. After five in vitro stimulations, the CTL were tested against uninfected JY cells, or infected with pp65 (pp65Vac) or wt (wtVac) vaccinia viruses. A non-HLA A2.1 EBVLCL was included as a control. The specificity of the CTL for pp65495-503 peptide was shown in an assay using peptide-loaded T2 cells using either the pp65 or a p53 HLA A2 epitope. A standard CRA was performed using 5,000 targets at an E:T of 2 (▥) and 20 (▪). (B) HCMV-infected fibroblasts are lysed by immunized splenic effectors. MRC-5 which expresses HLA A*0201 and non-HLA A*0201 fibroblasts were infected for 16 hours with HCMV strain AD169. The infected and noninfected fibroblasts were chromated, and 2,000 were used as targets for each point in a standard CRA using peptide-stimulated murine splenic effectors as in (A). Simultaneously, the recognition of peptide-loaded and nonloaded T2 cells was evaluated using the same effector population. (▥), E:T = 2; (▪), E:T = 20.

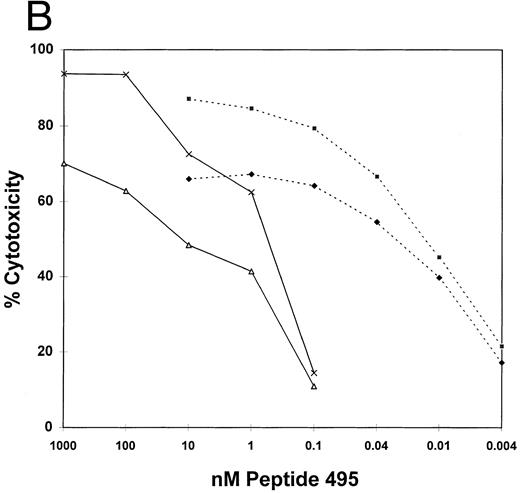

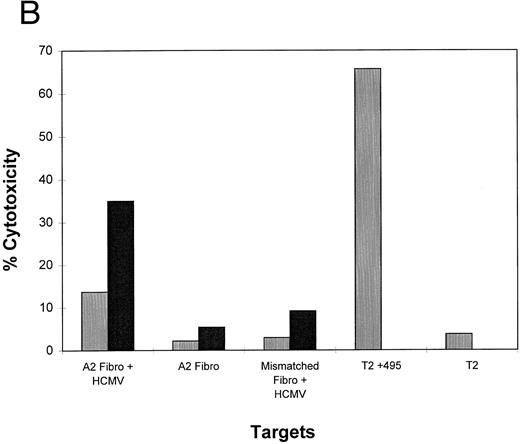

Lipidated peptides incorporating pp65495-503 as adjuvant independent vaccines.Use of adjuvants to enhance immunogenecity is a common strategy in animal studies, but there are severe limitations for human use. To bypass adjuvants, we have constructed peptides that incorporate lipid molecules at the amino terminus based on a proven strategy that has been efficacious in both animal59 and clinical studies.21 We have added either one or two palmitic acid moieties to the amino terminus of the pp65495-503 peptide, and conducted a series of immunization studies in the transgenic HLA A2.1 mice. The primary structure of the lipidated epitopes is shown in Table 3. Separate mice were immunized with unmodified pp65495-503 and either the monolipidated or dilipidated forms of the peptide. Because it has been previously shown that lipidated peptides will stimulate immunity without coadministration of Freund's adjuvant,60 we compared immunization of mice with and without emulsifying the peptides in IFA. Using a similar strategy of immunization with the PADRE HTL as described above, after 12 days the mice were splenectomized, and the spleen cell population was restimulated twice in vitro. The splenic effectors were then tested in a CRA with peptide loaded T2 cells, EBVLCL targets infected with pp65Vac, and HCMV-infected fibroblasts (Fig 6). The results are encouraging in that they show that the lipidated form of the CTL epitope without emulsification in adjuvant induces an immune response capable of recognizing endogenously processed pp65 and virus infected cells. To a lesser degree, the monolipidated form induces a weaker immune response (compare with and without IFA), whereas the unmodified CTL epitope free peptide is without activity unless it is emulsified in IFA.

Lipidated pp65495-503 peptide stimulates a cytotoxic immune response in HLA A2.1 transgenic mice. Mice were immunized with 50 nmol of either pp65495-503 peptide without lipid attached, one lipid attached, or two lipids attached together with the PADRE HTL peptide (20 μg) with or without IFA adjuvant. After 12 days mice were killed, spleens were removed, and the spleen cells restimulated as described in Materials and Methods for two cycles. A CRA was performed on all spleen cell suspensions at an E:T = 20. p53 and pp65 peptides were pulsed onto T2 cells, pp65 and wt Vacs were used to infect JY cells, and MRC-5 HLA A*0201 fibroblasts were either infected with HCMV AD169 (Fibro-CMV) or not (Fibro) as the targets for the CRA.

Lipidated pp65495-503 peptide stimulates a cytotoxic immune response in HLA A2.1 transgenic mice. Mice were immunized with 50 nmol of either pp65495-503 peptide without lipid attached, one lipid attached, or two lipids attached together with the PADRE HTL peptide (20 μg) with or without IFA adjuvant. After 12 days mice were killed, spleens were removed, and the spleen cells restimulated as described in Materials and Methods for two cycles. A CRA was performed on all spleen cell suspensions at an E:T = 20. p53 and pp65 peptides were pulsed onto T2 cells, pp65 and wt Vacs were used to infect JY cells, and MRC-5 HLA A*0201 fibroblasts were either infected with HCMV AD169 (Fibro-CMV) or not (Fibro) as the targets for the CRA.

DISCUSSION

Vaccination using subunits of viruses has been a successful strategy to prevent infection in humans for the last decade. As our understanding of the tenets of antigen processing and presentation become sharpened, the design of peptide vaccines has emerged as an alternative to more traditional approaches using attenuated or killed forms of whole virus as an immunogen. The critical element in a peptide vaccine approach is the ability of the MCE to bind to MHC molecules that are expressed in a major proportion of the population.55,61 62 Our findings show that an MCE can be isolated from a known immunogenic protein from HCMV pp65, and that the epitope binds to cells expressing HLA A*0201, and mediates their lysis by CTL.

An effective vaccine against HCMV will need to stimulate an immune response that results in the recognition of infected cells. We have shown that the pp65495-503 peptide can be used to amplify a memory CTL response to HCMV as reported here and in studies conducted subsequent to this report with additional subjects. Furthermore, in a transgenic mouse model of HLA A*0201, a primary response to the pp65495-503 peptide caused recognition of HCMV-infected fibroblasts. Splenocytes from mice immunized and restimulated in vitro with a different HLA A*0201 restricted epitope such as from human p53 (aa 149-157) did not recognize HCMV infected fibroblasts (J.S. and D.J.D., unpublished results, December 1996). We also found in preliminary studies that the PADRE HTL epitope was absolutely necessary to be included in the immunization, and that stimulation of naive splenocytes with peptide pp65495-503 from unimmunized mice did not induce recognition of HCMV-infected fibroblasts (J. Sun, M. Barth, and D.J. Diamond, unpublished results, March 1997). These results are suggestive that the CTL epitope pp65495-503 is the sole epitope used by humans who are HLA A*0201, to mediate the recognition and inhibition of active or latent HCMV infection. Further tests, either by in vitro immunization of human PBMC or dendritic cells, or vaccination of HCMV seronegative volunteers will answer whether it is possible to elicit primary immunity against HCMV using the CTL epitope defined here.

The pp65495-503 peptide was derived by initially showing that a T-cell clone recognized an endogenously processed form of pp65 expressed in EBVLCL targets as well as HCMV-infected fibroblasts. Truncation analysis narrowed a region of activity to a small segment between aa 477-561. From the truncation studies, it became feasible using motif algorithms to predict the active epitope. Algorithms for peptide motifs specific for particular HLA A alleles have been established by various groups using synthetic peptides and/or results of Edman degradation of peptidic material released from MHC class I molecules.18,63 This peptide possesses the preferred anchor residue leucine at position 2 and valine at position 9 of the established HLA A*0201 binding motif.55,62 As expected, the nonamer pp65495-503 peptide sensitized both T2 and JY cells to be killed by the T-cell clone 3-3F4. HLA A*0201 restricted CTL clones against HCMV pp65 have been recently reported by another group.64 Their CTL recognized both a 15mer and a decamer which overlaps our reported sequence. However, they did not report that the nonamer peptide is the MCE, and could function as an immunogen in both human in vitro and murine in vivo studies. Although similar in concept to the recently published report, our results extend the previous observations by demonstrating that the nonamer is the MCE, and it can act as a vaccine without adjuvant in the HLA A2.1 transgenic mouse model.

The pp65495-503 peptide was capable of stimulating PBMCs from seropositive individuals to lyse HCMV-infected fibroblasts, a necessary property of a CTL epitope-based vaccine. The difference in recognition of either CMV-infected or peptide-sensitized fibroblasts compared with the untreated control is reproducibly large, and comparable to the results we obtained with the 3-3F4 T-cell clone. Each target fibroblast was simultaneously incubated with the T-cell clone 3-3F4, and only the HLA-matched and peptide loaded or HCMV-infected fibroblasts were lysed, whereas the untreated control fibroblasts or HLA mismatched targets were not recognized (data not shown). Using a recently described approach of deriving antigen-specific clones using recombinant vaccinia stimulation of PBMCs,57 we have been able to derive pp65 CTL which recognize the pp65495-503 peptide using pp65Vac stimulation from additional individuals who are HLA A*0201 (P. Hao, J. York, C.L. Wright, S.J. Forman, and D.J. Diamond, unpublished results, April 1997).

Although a substantial number of CTL epitopes have been identified, it is clear that more peptide sequences bind to MHC class I molecules than are used by APC in developing functional immune responses. CTL epitopes which are defined as a result of their matching an algorithm may not always function as the endogenously processed epitope in vivo. We have conducted preliminary immunization studies using HLA A2.1 transgenic mice with peptides from pp65 predicted by motif algorithms51 65 to bind better to HLA A*0201 than pp65495-503 , the naturally processed epitope (J. Sun, M. Barth, and D.J. Diamond, unpublished results, May 1996). We found that nonamer peptides beginning at AA 14, 40, 227, 245, and 304 were capable of eliciting peptide-specific responses in the HLA A2.1 mice but, unlike the pp65495-503 peptide, the splenic effectors were unable to recognize endogenously processed pp65 (J. Sun, M. Barth, and D.J. Diamond, unpublished results, June 1996). It remains to be determined how the immune system in concert with the cellular peptide degradation pathway selects epitopes to be presented by APC, which are in turn recognized by CTL.

Our results showing that a lipidated pp65495-503 peptide can be used to elicit splenic effectors without adjuvant makes the epitope defined here a prime candidate as a vaccine for clinical studies (Fig 6). Studies are in progress to test whether a chimeric lipidated HTL/CTL molecule will function as a vaccine without adjuvant in the HLA A2.1 mouse model. This approach of using a chimeric peptide was shown earlier to be an effective means of stimulating primary immunity against HBV in asymptomatic volunteers.21 Preliminary results using a preparation of lipidated HTL/CTL vaccine are encouraging. We have immunized 2 mice with 50 or 100 nmol of peptide dissolved in DMSO/PBS. After two in vitro stimulations (IVS), we can detect potent lytic activity against HCMV-infected HLA A*0201 human fibroblasts, with little activity against the mismatch at E:T ratios as low as 20:1 (J. Sun, J.A. Zaia, and D.J. Diamond, unpublished results, June 1997).

The notion that an MCE epitope can function as a vaccine to stimulate CTLs that limit virus infection is the motivation for defining the MCE epitopes of immunogenic proteins from HCMV. Historically, there have been a wide range of approaches to induce protective immunity, although most strategies were designed to protect uninfected individuals from infection. A strategy conceived by Plotkin et al66,67 in the 1970s was to use an attenuated HCMV strain as a therapeutic vaccine; however, concerns about using live virus have minimized the generality of that approach. Other viral approaches to making vaccines, which include using either canarypox or vaccinia virus encoding an immunogenic viral protein, have the same caveat of caution during periods of immunosuppression.2,45,68 69 Recently, subunit vaccines against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HBV, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) have been designed to prevent the worsening of symptoms of infection in seropositive individuals. Our approach is analagous to these more recent strategies, because the goal is to prevent the reactivation of HCMV and the development of disease in seropositive BMT recipients.

Alternatively, some have suggested the use of full-length proteins as immunogens to achieve the goal of sustaining long-term immunity.70-72 The success of this approach depends on the introduction of the protein into the cell such that it will be recognized and processed as an endogenous protein. There are few effective approaches of chaperoning a protein across the plasma membrane so it will be processed by the class I degradation pathway. Several studies have focused on the use of either adjuvants or liposomes. The current status of adjuvant research is not sufficiently advanced that one can reliably predict that a particular adjuvant will lead to the production of systemic and long-lived antigen-specific CTL.72,72 Other approaches that show promise in animal models include introduction of DNA vectors encoding the immunogenic protein as a means to elicit protective CTL.74-76 At this early stage in their development it remains unknown whether these subunit protein or DNA vaccines will be effective and safe in clinical studies. The development of a vaccine against HCMV based on the use of CTL epitopes is dependent on the presence of frequent HLA alleles in the general population. The gene frequency of predominant alleles in separate ethnic groups that comprise a national population will determine the potential relevance of isolating corresponding CTL epitopes from HCMV. Statistical studies have shown that a large proportion of many ethnic populations express at least one of a small number of HLA-A or B alleles. This suggests that identifying a limited number of CTL epitopes from HCMV would allow the formulation of a more generalized vaccine strategy.22,61 This is especially relevant because several studies, including our own, suggested that the human immune response against HCMV is limited to a few proteins, with the predominant response directed against pp65, followed by a much lower frequency response against pp150, with almost no response against all other HCMV-expressed proteins.12,64,77 This fortuitous situation suggests that defining CTL epitopes among the most frequent HLA-A and B alleles for pp65 and pp150 would provide enough information for a vaccine strategy applicable to most people. In fact, the identification of just five CTL epitopes from pp65 would potentially enable the vaccination of greater than 97% of the Dutch population who are CMV seropositive.61

Because it has been difficult to develop an effective means to immunize with whole protein in such a way that CTL development occurs,72,73 a practical alternative is to use the MCE as part of single or multi-CTL epitope vaccine to induce CTL.21,78 Our approach for in vivo immunization is to use the MCE defined for viral antigen to boost a CTL memory response to a virus. Properly administered, the MCE can serve as a potent vaccine, because of its property of direct binding to MHC class I molecules without the need for further cellular processing. However, it is known that to stimulate a CTL response, the non–lipid-modified MCE must be suspended in a strong adjuvant.60,79,80 We have also found that strong adjuvants such as IFA are necessary to stimulate immune responses to CTL epitopes as described in Fig 5. This is an apparent obstacle because the preferred clinical strategy is to use less harsh reagents as adjuvants such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved alum, or saponin containing adjuvants such as QS-21.81

An alternative strategy that has gained favor is to use lipidated peptides as part of a vaccine against infectious diseases, as reported here. Studies originating in 1989 in the laboratory of Rammensee, have shown the utility of lipidated CTL epitopes administered in the absence of strong adjuvants at eliciting CTL against influenza in several different mouse models.59,82,83 Several groups have also explored vaccinating macaques or mice in the absence of adjuvant, and have obtained good immune responses using lipidated CTL epitopes from HIV.84,85 In addition, safety studies have shown that the lipid moiety does not cause skin inflammation and is safer than many alternatives.86 87 We have extended this approach in studies with the murine transgenic model in which the lipidated CTL epitope is coimmunized with an HTL epitope (Fig 6). Our successful murine immunization with the lipidated PADRE HTL epitope covalently attached to the pp65495-503 as a single moiety, although preliminary, suggests a method of administering the vaccine for clinical use without the need for adjuvant.

Several obstacles still remain for achieving long-lived immunity using a CTL epitope vaccine with or without prior viral infection. Studies by Vitiello et al21 suggest that primary immunization with 500 μg of a lipidated combined CTL/HTL epitope and a single boost will result in the induction of HBV-specific CTL. In contrast to their murine studies with a similar molecule where specific memory CTL were detectable more than 1 year later, the CTL in human PB declined within a month of immunization. The HBV study used the tetanus 830-843 AA peptide to stimulate T-help. Later studies have shown this peptide to be less efficient at stimulating T-help in humans than the PADRE peptide used here.38 Whether infection by virus subsequent to immunization would cause a true secondary response is uncertain, and it remains a challenge to develop an efficacious vaccine without live virus to establish long-term immunity in seronegative individuals.

Since the inception of BMT as a therapy for hematologic malignancies, one of the most difficult infectious complications is pneumonia caused by HCMV infection.88,89 Various attempts over the last 15 years have been made to control the pathologic consequences of HCMV infections. Although initial strategies focussed on the use of HCMV immune-globulin to control the spread of infection, later studies have shown that CD8+ CTL development is necessary to control HCMV infection and prevent IP (interstitial pneumonia) in BMT recipients.88-92 Pharmacologic agents that limit virus replication, such as acyclovir, and more recently, ganciclovir and foscarnet, have become the methods of choice for prophylaxis of HCMV infection over the past 5 years.93-95 Nonetheless, there are significant side effects of these drugs, especially in the setting of immunosuppression after BMT.96,97 Such disadvantages to ganciclovir prophylaxis include cost of the drug, severe hematologic side effects, and a delay in the development of CD8+ CTL leading to late-stage IP after the cessation of drug treatment.41

Alternative strategies exist that are effective in limiting complications of HCMV in the setting of BMT. Elegant studies using antigen-specific adoptive immunotherapy have been used successfully to limit HCMV infections after BMT.93,95 98 These seminal studies provided the impetus to identify MCE as a potential immunogen to augment donor and possible host immunity to CMV. In addition, an effective and safe HCMV vaccine might be useful in situations other than BMT. An HCMV vaccine could have application for other at-risk groups, including solid organ donors, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, and seronegative women of childbearing years.

As the period of maximal immuno-incompetence after BMT is relatively short, it provides an appropriate setting to test whether an HCMV vaccine would confer protective immunity for a short duration (<6 months), until normal immunocompetence is reestablished in the recipient.99,100 Because many BMT recipients are unable to mount an effective immune response immediately after transplant when the risk for IP is the greatest, we have considered a strategy of immunizing the marrow donor. Studies to determine whether there is transfer of humoral and cellular immunity after BMT have been conducted over the past 15 years. The consensus is that humoral immunity is transferred, especially after vaccination of the donor and recipient.101 102

The case for cellular immunity is more guarded. Vaccination of BMT donors against pertussis, measles, and mumps showed almost no transfer to the recipient,103 and donor reactivity to varicella zoster was rarely transmitted to recipients.104 Yet it has been shown for HCMV, EBV, hepatitis B, and in one case of myeloma, that it is possible to transfer donor cellular immune responses to recipients of BMT.105-108 More predictably, expansion of donor-derived antigen-specific HCMV or EBV T-cell clones in vitro, and their subsequent adoptive transfer to BMT recipients is an effective means of limiting disease.15,106,109 These studies are suggestive of a CD8+ CTL-dependent means of controlling infection, which agrees with studies showing the absolute dependence of protection from IP on the establishment of a CTL response.88,89,92 110 Therefore, it is plausible that vaccinating a BMT donor with a CTL epitope which induces the proliferation of CTL which lyse HCMV-infected cells might be sufficient in imparting immunity to the BMT recipient during the critical period after transplant. This is a candidate strategy to immunize individuals at risk for reactivation of HCMV in the transplant setting or establishing primary immunity in immunocompetent individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the members of the COH Blood Bank and its director Dr I. Sniecinski and supervisor, Linda Aldridge, for providing quality blood products. Construction of vaccinia viruses and expression plasmids was accomplished by Drs Takuya Tsunoda and Xiping Liu with the aid of Hsinyi Chang. The WEHI-164 cell line was gratefully donated by Dr N. Ruddle. Drs V. Engelhard and W. Britt are gratefully acknowledged for providing us with HLA A2.1 transgenic mice, and recombinant vaccinia viruses for several HCMV proteins, respectively. We appreciate the time and effort devoted by Dr Z.W. Yu in teaching us how to raise murine CTL. Dr J.D.I. Ellenhorn is thanked for procuring skin biopsy specimens and for his acumen as an immunologist in critically reviewing the manuscript. Drs Stan Riddell and Phillip Greenberg are thanked for their advice, including the suggestion of the use of HAB for CTL generation. Drs R.F. Siliciano and J.A. Zaia are gratefully acknowledged for providing continuous and professional expertise in reviewing the manuscript and making suggestions for its improvement.

Supported by US Public Health Service Grant No. PO1-CA30206 and Clinical Cancer Research Center Grant No. CA33572 to the City of Hope.

Address reprint requests to Don J. Diamond, PhD, Department of Hematology and BMT, City of Hope Medical Center, 1500 E Duarte Rd, Duarte, CA 91010.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal