Abstract

Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation events in human blood platelets were investigated during their adhesion to collagen under flow conditions. Using 32P-labeled platelets and one-dimensional gel electrophoresis, we found that adhesion to collagen mediated primarily by the α2β1 integrin resulted in a strong dephosphorylation of several protein bands. Neither adhesion to polylysine nor thrombin-induced aggregation caused similar protein dephosphorylation. In addition, treatment with okadaic acid (OA), an inhibitor of serine/threonine protein phosphatases type 1 (PP1) and 2A (PP2A), caused significant inhibition of adhesion, suggesting that adhesion is regulated by OA-sensitive phosphatases. Recent studies indicate that phosphatases may be associated with the heat-shock proteins. Immunoprecipitations with antibodies against either the heat-shock cognate protein 70 (hsc70) or heat-shock protein 90 (hsp90) showed the presence of a phosphoprotein complex in 32P-labeled, resting human platelets. Antibody probing of this complex detected hsc70, hsp90, two isoforms of the catalytic subunit of PP1, PP1Cα and PP1Cδ, as well as the M regulatory subunit of PP1 (PP1M). OA, at concentrations that markedly blocked platelet adhesion to collagen, caused hyperphosphorylation of the hsc70 complex. In platelets adhering to collagen, hsc70 was completely dephosphorylated and hsp90, PP1α, and PP1M were dissociated from the complex, suggesting involvement of heat-shock proteins and protein phosphatases in platelet adhesion.

INTEGRIN-MEDIATED adhesion events are involved in many biologic functions such as development, tumor cell growth and metastasis, apoptosis, hemostasis, and the response of cells to mechanical stress.1 Binding of extracellular matrix proteins to integrins initiates cell signaling and the formation of focal adhesions that link integrins to cytoskeletal complexes and actin filaments.2 Heat-shock proteins (hsp) are a group of abundant and highly conserved molecules with important roles in the response of cells to environmental stress. Members of the 70- and 90-kD hsp families can associate with the cytoskeleton, bind to actin and tubulin, and participate in intracellular protein transport.3-9 There is evidence that these hsps are involved in regulating the activities of signaling molecules such as the steroid hormone receptors and several protein kinases, including pp60v-src, Raf, the initiation factor (eIF )-2α kinase, and casein kinase II.10 In humans, the hsp70 family consists of at least four members: the heat-shock cognate protein 70 (hsc70), hsp70, the glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78; also known as BiP), and hsp75.11 The Na+/H+ exchanger, which responds to integrin-activated signaling, has been shown to form a complex with hsp70.12 Tyrosine phosphorylation of hsc70 in response to ligation of T-cell antigen receptors and of a 75-kD protein, a member of the hsp70 family, in response to oxidative stress has been reported.13,14 Integrin-mediated signaling may also involve phosphoprotein phosphatases that are essential to preserve focal adhesions, to regulate cytoskeletal structure, and to maintain the structural integrity of intermediate filaments and microtubules.15-17 A critical role for the okadaic acid (OA)-sensitive protein phosphatases type 1 (PP1) and 2A (PP2A) in binding of the αLβ2 integrin to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and in adhesion via the α4 integrins to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 has been proposed.18,19 Dedhar and Hannigan20 have suggested that the association of signaling molecules, such as calreticulin, with the cytosolic tail of the β1 integrin and integrin activation may depend on dephosphorylation/phosphorylation events involving serine/threonine protein phosphatases and kinases. However, there have been no investigations of possible interactions between heat-shock proteins and protein phosphatases during integrin-activated signal transduction after cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix.

Platelet adhesion to collagen is one of the first steps in hemostasis when blood vessels are injured.21 Several membrane proteins have been proposed as collagen receptors, including glycoprotein (GP) Ia/IIa (α2β1 integrin), GPIV, and GPVI.22-25 However, it is uncertain which receptor serves as the major mediator of platelet adhesion to collagen or which one plays a signaling role. We previously described an approach for studying the initial events of adhesion to collagen under flow conditions.26 Immuno-inhibition experiments with the antibodies directed against different platelet receptors showed that adhesion to collagen in a plasma-free medium is primarily mediated by the α2β1 integrin.27 Use of a continuous-flow microcolumn adhesion approach26 enables investigating adhesion under arterial-flow conditions in the absence of secretion and αIIbβ3 integrin-mediated aggregation. 32P-labeled human platelets are pumped over a microcolumn of collagen-coated Sepharose beads to permit analysis of sub-second adhesion kinetics and rapid biochemical events.28 29 In the present study, we have focussed on protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation changes and the involvement of hsc70, hsp90, and serine/threonine phosphoprotein phosphatases during adhesion to collagen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and antibodies.Native, salt-soluble type I collagen from rat skin was donated by Dr Gary Balian (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA). A purified rat monoclonal antibody (MoAb) 1B5 against constitutively expressed heat-shock cognate protein 70 (hsc70), a mouse MoAb N27 (N27F3-4) against both the constitutive and inducible forms of human hsp70, and a mouse MoAb AC88 against hsp90 isolated from the water mold Achlya ambisexualis and cross-reacting with hsp90 from a variety of vertebrate species were all purchased from StressGen Biotechnologies Corp (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada). A mouse MoAb 13D3 recognizing hsc70 was obtained from Affinity BioReagents, Inc (Golden, CO). Purified bovine hsc70 and hsp90 were from StressGen Biotechnologies Corp. Nonimmune rat IgG was from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO). Nonimmune mouse IgG was from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). A polyclonal antibody recognizing the α catalytic subunit of PP1 was obtained from UBI (Lake Placid, NY). A polyclonal antibody to the δ catalytic subunit of PP1 was a gift from Dr John Lawrence (University of Virginia) and a polyclonal antibody recognizing the M regulatory subunit of PP1 was a gift from Dr David Hartshorne (University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ). [32P]-orthophosphate (carrier-free) was from Amersham Corp (Arlington Heights, IL). OA was from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The Immun-Lite chemiluminescent assay was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA), and other specialty chemicals used were from Sigma Chemical Co.

Preparation of human platelets.Human venous blood was anticoagulated with acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD) buffer to a final citrate concentration of 11.5 mmol/L in whole blood and centrifuged at 350g twice for 3 minutes and once for 5 minutes, all at room temperature. The resultant platelet-rich plasma was mixed with 0.05 vol of ACD and with inhibitors of platelet activation (apyrase [7.5 U/mL ADPase activity], indomethacin [1 μg/mL], and prostacyclin I2 [0.3 μg/mL]) and centrifuged at 620g for 20 minutes. The platelet pellet was then resuspended in phosphate-free buffer (140 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 0.05 mmol/L CaCl2 , 0.1 mmol/L MgCl2 , 0.01 g/mL bovine serum albumin [BSA], 16.5 mmol/L glucose, 15 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.35) containing 1 μg/mL indomethacin and left for 20 minutes before incubation with 0.1 mCi/mL carrier-free [32P]-orthophosphate for 90 minutes at 37°C. After a further wash, the platelets were resuspended at 6 × 108 cells/mL in a modified BSA-free Tyrode's-HEPES buffer (140 mmol/L NaCl, 0.34 mmol/L Na2HPO4 , 2.9 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 12 mmol/L NaHCO3 , 5 mmol/L glucose, 2 mmol/L MgCl2 , pH 7.4). Because collagen activation may lead to the formation of thromboxane A2 from arachidonate via cyclooxygenase and release of ADP from platelet dense granules, we added indomethacin (10 μmol/L) and apyrase (7.5 U/mL) to the platelet suspension to block any possibility of secondary stimulation by these platelet agonists. To prevent thrombin generation, hirudin (0.01 U/mL) was also included in the suspension buffer. Neither inhibitor affected adhesion.27

Platelet adhesion and aggregation assay.The continuous-flow adhesion approach was essentially as described.26 29 CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads were coated either with native soluble collagen type I from rat skin or with polylysine. Platelets and isotonic saline were pumped through a microcolumn of 50 μL of beads at a pumping speed of 3.4 μL/s, giving a shear rate of about 1,700 s−1 and a contact or adhesion time of 1.35 seconds. Adhesion was determined by counting single platelets in the suspension before and after exposure to the beads and is expressed as the percentage of platelets bound to collagen. To assess the changes in protein phosphorylation during adhesion, usually 250 μL of 32P-labeled platelets (1.5 × 108) suspended in a Tyrode's-HEPES buffer were pumped through a column at 37°C for 90 seconds. Knowing the percentage of platelet adhesion under the above flow conditions, usually set to give approximately 50%, identical amounts of resting (unstimulated), effluent (flow-through), and adherent platelets were solubilized for the electrophoresis and immunoprecipitation experiments described below. In some experiments, platelets were treated with 0.1 and 1 μmol/L OA dissolved in 0.1% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 10 minutes at 37°C. Control platelets were incubated with 0.1% (vol/vol) DMSO.

For aggregation experiment, platelets were stirred with 1 U/mL thrombin at about 1,000 rpm for 90 seconds at 37°C and aggregation was assessed by following the decrease in numbers of single platelets. A 10-fold excess of hirudin was used to neutralize thrombin before treating with lysis buffer.

Electrophoresis, immunoblotting, and immunoprecipitation.Collagen- and polylysine-adherent, thrombin-aggregated, and control (resting and effluent) platelets were all solubilized at 4°C with a low-salt lysis buffer containing 1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors29 followed by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-containing buffer (2% SDS [wt/vol], 5% 2-mercaptoethanol [vol/vol], 10% glycerol [vol/vol], 0.002% bromophenol blue [vol/vol], and 62.5 mmol/L Tris, pH 6.8). Proteins corresponding to 1.5 × 107 platelets were applied to each lane and were separated by vertical electrophoresis on 1.5-mm–thick and 20-cm–long SDS-polyacrylamide (8% and 12%) slab gels, stained with Coomassie blue, destained overnight, and dried. The dried gels were exposed to x-ray film at −80°C.

For immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting experiments, proteins were separated and electro-transferred using the Mini-Protean II system (Bio-Rad). Briefly, lysates from 5 × 108 platelets in the low-salt lysis buffer29 were first usually cleared of debris by centrifugation at 15,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C and then incubated overnight at 4°C with different antibodies, followed by the addition of a rabbit antirat or rabbit antimouse IgG bound to protein A-Sepharose beads. The low-salt lysis buffer was chosen to minimize dissociation of protein complexes. The immune complexes bound to protein A beads were washed twice in the low-salt lysis buffer and twice in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2. After final washing, platelet proteins were solubilized off the beads by heating in SDS-containing buffer and separated on minigels usually by 8% or 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). When required, gels were stained by either Coomassie Brilliant blue or silver nitrate using the Bio-Rad silver stain kit as described by the manufacturer. For autoradiography, the gels were dried and exposed to x-ray film. When Western blots were required, the resolved proteins were electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, followed by blocking with 5% BSA (wt/vol) in a buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.1% Tween (vol/vol), pH 7.5. Western blotting and detection were by enhanced chemiluminescence techniques.

Platelet fractionation.Adherent and control (resting) cells were first lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer as described above. Subcellular platelet fractions were obtained according to Fox et al,30 but with slight modifications. Samples (1 × 109 platelets/mL) were vigorously mixed and left on ice for 30 minutes. Platelet cytoskeletons were isolated by centrifugation at 15,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant (detergent-soluble fraction) was removed and centrifuged at 100,000g for 3 hours at 4°C to obtain a pellet (membrane-skeleton fraction) and supernatant (cytosolic fraction). The cytoskeletal and membrane-skeletal pellets were resuspended in 200 μL of SDS-containing buffer. The detergent-soluble supernatants were mixed at a ratio of 1:3 with 4 times concentrated (4×) SDS-containing buffer. Thus, the final detergent-insoluble samples (both cytoskeleton and membrane-skeleton fractions) were concentrated approximately 7 times relative to the detergent soluble fractions. The platelet fractions were boiled, subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE, electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted with the anti-hsp90 antibody, AC88.

Peptide sequencing.The 32P-labeled 67-kD protein band obtained by gel electrophoresis was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and digested in situ with trypsin.31 Sequencing of an aliquot of the digest was performed using microcapillary high-pressure liquid chromatography followed by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry.32

RESULTS

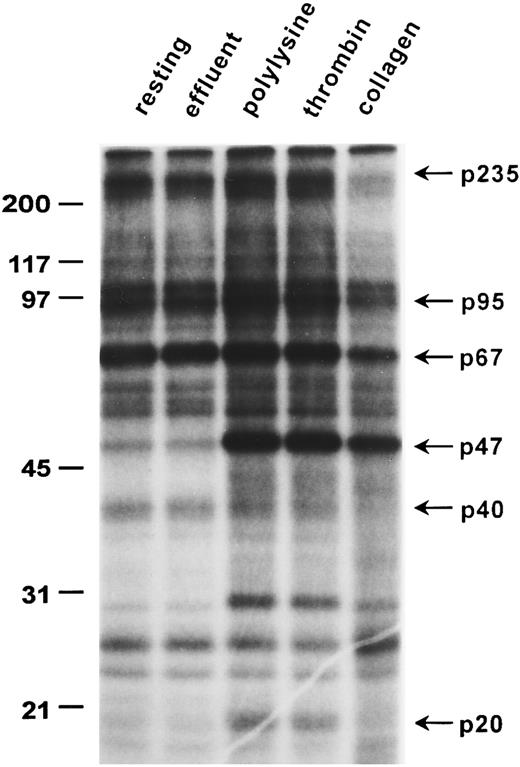

Platelet protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation changes induced by adhesion to collagen.One-dimensional gel electrophoresis of 32P-labeled human platelet proteins shows that platelet adhesion to collagen caused marked phosphorylation of pleckstrin, a 47-kD protein (p47; Fig 1) usually used as an index of protein kinase C (PKC) activation33 and the dephosphorylation of unknown protein bands of apparent molecular weights of 235, 220, 120, 100, 95, 67, and 40 kD, which were the major phosphorylated proteins in unstimulated platelets (Fig 1). Moreover, adhesion to collagen also increased phosphorylation of a 26-kD protein band, unlike polylysine or thrombin-activated platelets. In contrast to adhesion to the nonspecific substrate polylysine or thrombin-induced aggregation, adhesion to collagen did not induce significant phosphorylation of the 20-kD (p20) myosin light chains (Fig 1). Pleckstrin phosphorylation occurred in platelets stimulated with thrombin, as expected, but was also found in platelets adherent to polylysine. Analysis of platelets emerging in the effluent from the microcolumn show that shear forces acting alone26 29 or brief contact with collagen during flow through the beads caused little change in overall phosphorylation patterns (effluent; Figs 1 and 2). The dephosphorylation of the protein bands mentioned above was specific for collagen-induced adhesion, because it was not induced by adhesion to polylysine or by thrombin-induced aggregation. Although very similar labeling patterns were observed for 6 donors in 10 separate gels, there was some donor variability in the relative intensity of dephosphorylation observed in adherent platelets. Thus, dephosphorylation of a 40-kD protein band (Fig 1) was less apparent in some experiments (Fig 2). Nevertheless, we consistently observed dephosphorylation of the various bands in 10 of 10 experiments.

Adhesion-induced dephosphorylation of a 67-kD protein band. Washed, 32P-labeled human platelets were used to assess changes in phosphorylation caused either by adhesion to collagen and polylysine or by thrombin-induced aggregation as described in the Materials and Methods. Whole cells lysates from 1.5 × 107 platelets were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE full-size gels: “resting” refers to control unstimulated platelets; “effluent” refers to platelets that failed to adhere to collagen; “polylysine” refers to platelets adherent to polylysine; “collagen” represents platelets adherent to collagen; and “thrombin” refers to platelets aggregated by thrombin (1 U/mL). Molecular weight standards (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left, and the weights of some protein bands altered by adhesion are indicated on the right. An autoradiogram representative of six experiments is presented.

Adhesion-induced dephosphorylation of a 67-kD protein band. Washed, 32P-labeled human platelets were used to assess changes in phosphorylation caused either by adhesion to collagen and polylysine or by thrombin-induced aggregation as described in the Materials and Methods. Whole cells lysates from 1.5 × 107 platelets were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE full-size gels: “resting” refers to control unstimulated platelets; “effluent” refers to platelets that failed to adhere to collagen; “polylysine” refers to platelets adherent to polylysine; “collagen” represents platelets adherent to collagen; and “thrombin” refers to platelets aggregated by thrombin (1 U/mL). Molecular weight standards (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left, and the weights of some protein bands altered by adhesion are indicated on the right. An autoradiogram representative of six experiments is presented.

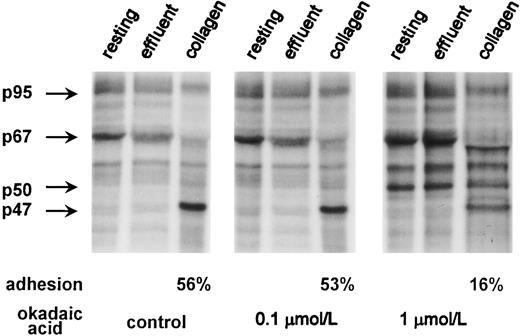

Effect of phosphoprotein phosphatase inhibition by OA on dephosphorylation of the 67-kD protein band. 32P-labeled platelets (6 × 108 platelets/mL) were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with 0.1 and 1 μmol/L OA or with buffer for 10 minutes and then used for adhesion experiment as in Fig 1. Adhesion (as a percentage) is shown for the control and OA-treated cells. Lysates from 1.5 × 107 platelets were applied per each lane and analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE full-size gels. Phosphorylation patterns for the 47-(pleckstrin), 50-, 67-, and 95-kD protein bands are shown on the left. An autoradiogram representative of three experiments is presented.

Effect of phosphoprotein phosphatase inhibition by OA on dephosphorylation of the 67-kD protein band. 32P-labeled platelets (6 × 108 platelets/mL) were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with 0.1 and 1 μmol/L OA or with buffer for 10 minutes and then used for adhesion experiment as in Fig 1. Adhesion (as a percentage) is shown for the control and OA-treated cells. Lysates from 1.5 × 107 platelets were applied per each lane and analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE full-size gels. Phosphorylation patterns for the 47-(pleckstrin), 50-, 67-, and 95-kD protein bands are shown on the left. An autoradiogram representative of three experiments is presented.

Effect of OA on adhesion and adhesion induced dephosphorylation.Significant evidence exists for the involvement of protein phosphatases in platelet function, both serine/threonine linked34 and tyrosine linked. 35 Most reports on serine/threonine phosphatases have concerned platelet aggregation and were often based on the use of OA and calyculin A, which are the strong inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A.36,37 Thus, Chiang37 suggested that PP1 is involved in collagen-induced aggregation. However, there are few studies on the role of protein phosphatases in platelet adhesion, and because protein dephosphorylation during adhesion could result from phosphatase activation, it is possible that their inhibition would block adhesion.

The involvement of protein phosphatases was therefore studied by using OA at concentrations of 0.1 and 1 μmol/L, respectively. We found that 10 minutes of preincubation with 0.1 μmol/L OA had little influence on platelet adhesion to collagen, causing only 2.6% inhibition compared with controls studied at the same adhesion time (Table 1). Treatment of resting platelets with 1 μmol/L OA significantly blocked subsequent adhesion (60%; Table 1). The extent and pattern of protein phosphorylation at 0.1 μmol/L OA were similar to those that were observed for untreated cells (Fig 2), whereas 1 μmol/L OA caused a marked phosphorylation of a 50-kD protein and a moderate increase in phosphorylation of 67-kD and 95-kD protein bands (Fig 2). Those platelets that actually managed to adhere to collagen in the presence of OA were still able to stimulate phosphatase activity as indicated by dephosphorylation of the 67-kD protein band and by comparison with OA-treated nonadherent (both resting and effluent) platelets. A 50-kD protein band that was phosphorylated during OA treatment was also dephosphorylated in adherent platelets compared with control OA-treated cells. Interestingly, a new unknown phosphorylated protein band slightly below 67 kD appeared in adherent cells.

Effect of OA on Platelet Adhesion to Collagen Mediated by the α2β1 Integrin

| Experimental Situation . | Extent of Adhesion (% singlets bound) . | Inhibition (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 51.0 ± 2.9 | 0 |

| OA (0.1 μmol/L) | 49.7 ± 2.9 | 2.6 |

| OA (1.0 μmol/L) | 20.3 ± 2.0 | 60.2 |

| Experimental Situation . | Extent of Adhesion (% singlets bound) . | Inhibition (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 51.0 ± 2.9 | 0 |

| OA (0.1 μmol/L) | 49.7 ± 2.9 | 2.6 |

| OA (1.0 μmol/L) | 20.3 ± 2.0 | 60.2 |

Washed platelets were pumped through a micro-adhesion column containing collagen-coated Sepharose beads at a shear rate of 1,700 s−1, giving an adhesion or contact time of 1.37 seconds, as described in the Materials and Methods. Where indicated, the platelets were pretreated with either 0.1 or 1 μmol/L OA dissolved in 0.1% (vol/vol) DMSO for 10 minutes at 37°C. Control platelets were incubated with 0.1% (vol/vol) DMSO. Adhesion data are means ± SD from three separate platelet preparations, with nonspecific adhesion of 7% having been subtracted from these values.26 The inhibition data reflect the percentage of effect of OA compared with the control adhesion value.

Presence of hsc70 in the 67-kD protein band.An initial aim of our study was to identify proteins present in the 67-kD protein band that was dephosphorylated during adhesion to collagen and that was sensitive to OA treatment (Figs 1 and 2). Microsequencing of proteins in this band conclusively identified the presence of hsc70 based on detection of the following sequences: VEXXANDQGNR, TTPSYVAFTDTER, FEEXNADLFR, and DAGTXAGXNVXR (in which X stands for either Leu or Ile that cannot be distinguished under the low-energy collision conditions that were used). Using a database, exact matches were found for all sequences to a human 71-kD heat-shock cognate protein (hsc70).38

Immunoprecipitation of human platelet hsc70.It is known that small hsps are present in platelets and that their phosphorylation state can change during platelet activation.39-41 Recent observations suggest regulation of protein phosphatase activity not only by small hsps, but also by a group of hsps of higher molecular weight.42-44 Our finding that hsc70 was present in the 67-kD protein band helped stimulate us to study the association of hsc70 with platelet protein phosphatases and their possible involvement during cell adhesion to collagen. The hsc70 represents a constitutive member of the hsp70 family of stress proteins, which usually act as molecular chaperones in protein folding45 and recently have been proposed as important signaling molecules capable of associating with protein kinases, transcription factors, and receptors.46 We immunoprecipitated hsc70 from 32P-labeled, resting platelets using a purified anti-hsc70 rat MoAb (1B5) or a nonimmune rat IgG as nonspecific control. Immunoblotting with anti-hsc70 1B5 antibody of either whole-platelet lysates or of anti-hsc70 immunoprecipitates showed that these resting platelets contained a protein recognized by the anti-hsc70 MoAb having an apparent molecular weight of 67-71 kD and that migrated identically to purified bovine brain hsc70 (Fig 3A). Nonspecific binding of control rat IgG to this platelet protein was not observed (Fig 3A). Based on these observations, we suggest that the 67-71–kD protein seen in the immunoblots contains platelet hsc70. We wish to note that the molecular weight of this protein when determined from full-size 20-cm–long slab gels was about 67 kD. However, when the molecular weight analysis was performed using minigels, its apparent molecular weight was about 71 kD. Consequently, we have termed this protein a 67-71–kD protein.

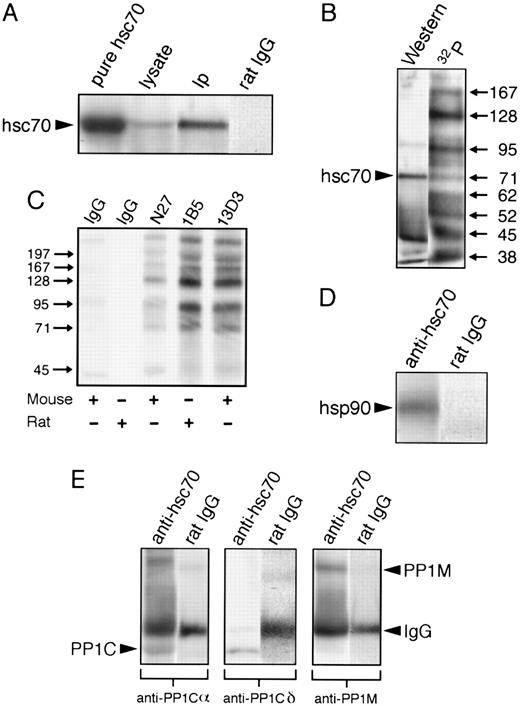

hsc70 forms a complex with hsp90 and PP1. hsc70 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of 5 × 108 resting platelets with MoAb 1B5 and probed with the indicated antibodies. 32P-labeling, immunoprecipitations (Ips), gels, and immunoblotting were as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) hsc70 in resting platelets. Preparations were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE minigels and immunoblotted with anti-hsc70 antibody 1B5. Pure hsc70 refers to 5 μg of purified hsc70; lysate refers to a whole-platelet lysate from 1.1 × 107 platelets; IP refers to an anti-hsc70 Ip; and rat IgG refers to a control Ip with nonimmune rat IgG. (B) hsc70 phosphoprotein complex. Both lanes represent anti-hsc70 Ips of 32P-labeled resting platelets. Western is an anti-hsc70 immunoblot; 32P is an autoradiogram. (C) Autoradiogram of immunoprecipitates from control (resting) platelets with nonimmune rat and mouse IgGs, and with specific MoAbs against hsc70 (N27, 1B5, and 13D3). Immunoprecipitates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE minigels. (D) hsc70 complex with hsp90. Both lanes are Ips of resting platelets blotted with anti-hsp90. Anti-hsc70 is an anti-hsc70 Ip; rat IgG is a nonimmune rat IgG Ip. (E) hsc70 complex with PP1. Resting platelet Ips were blotted with antibodies raised against different subunits of PP1. Anti-hsc70 is an anti-hsc70 Ip; rat IgG is a nonimmune rat IgG Ip. The lower labels indicate the antibodies used for blotting. The arrow labels designate specific proteins; PP1C identifies PP1Cα and PP1Cδ, which migrated similarly.

hsc70 forms a complex with hsp90 and PP1. hsc70 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of 5 × 108 resting platelets with MoAb 1B5 and probed with the indicated antibodies. 32P-labeling, immunoprecipitations (Ips), gels, and immunoblotting were as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) hsc70 in resting platelets. Preparations were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE minigels and immunoblotted with anti-hsc70 antibody 1B5. Pure hsc70 refers to 5 μg of purified hsc70; lysate refers to a whole-platelet lysate from 1.1 × 107 platelets; IP refers to an anti-hsc70 Ip; and rat IgG refers to a control Ip with nonimmune rat IgG. (B) hsc70 phosphoprotein complex. Both lanes represent anti-hsc70 Ips of 32P-labeled resting platelets. Western is an anti-hsc70 immunoblot; 32P is an autoradiogram. (C) Autoradiogram of immunoprecipitates from control (resting) platelets with nonimmune rat and mouse IgGs, and with specific MoAbs against hsc70 (N27, 1B5, and 13D3). Immunoprecipitates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE minigels. (D) hsc70 complex with hsp90. Both lanes are Ips of resting platelets blotted with anti-hsp90. Anti-hsc70 is an anti-hsc70 Ip; rat IgG is a nonimmune rat IgG Ip. (E) hsc70 complex with PP1. Resting platelet Ips were blotted with antibodies raised against different subunits of PP1. Anti-hsc70 is an anti-hsc70 Ip; rat IgG is a nonimmune rat IgG Ip. The lower labels indicate the antibodies used for blotting. The arrow labels designate specific proteins; PP1C identifies PP1Cα and PP1Cδ, which migrated similarly.

Coimmunoprecipitation of 32P-labeled hsc70 with other phosphoproteins in resting platelets.Autoradiograms of 32P-labeled platelet proteins immunoprecipitated with the anti-hsc70 1B5 antibody in seven separate immunoprecipitation experiments consistently showed 10 phosphoprotein bands possessing apparent molecular weights of 197, 167, 128, 102, 95, 82, 62, 52, 45, and 38 kD (Fig 3B), in addition to the 67-71–kD protein recognized by anti-hsc70 antibody. Because hsc70 is an abundant protein in cells, it is important to note that these 10 phosphoproteins might associate with hsc70 in a nonspecific manner. To clarify this issue, we immunoprecipitated hsc70 and associated phosphoproteins from 32P-labeled platelets by using two additional MoAbs against hsc70: a purified mouse MoAb (N27) and a mouse MoAb (13D3). Nonimmune mouse and rat IgGs served as controls (Fig 3C). Autoradiography of SDS-polyacrylamide gels showed a very similar pattern of distinct bands in platelets immunoprecipitated with the three anti-hsc70 MoAbs (1B5, N27, and 13D3), but not with the control antibodies. The fact that the different anti-hsc70 MoAbs immunoprecipitated essentially the same amount of protein (Coomassie blue stain; data not presented) and phosphoproteins (Fig 3C), which migrated similarly, suggests specific interactions between hsc70 and the other phosphoproteins. As just noted, the phosphorylation patterns obtained with the different antibodies (Fig 3C) were very similar for the same donor. However, we have observed that there was some variation in the extent of phosphorylation of the lower molecular weight components in the hsc70 complex for different donors.

Coimmunoprecipitation of platelet hsp90 and PP1 with hsc70.Based on evidence in other cells that hsp70 may associate with hsp9045 and interact with phosphoprotein phosphatases,44 we performed additional experiments in which either anti-hsc70 (1B5) or nonimmune IgG immunoprecipitates were blotted with antibodies against hsp90 (AC88) and the catalytic and targeting subunits of PP1. This approach showed that the hsc70-associated 95-kD band (Fig 3B) corresponded to hsp90 (Fig 3D), the 38-kD band (Fig 3B) to the α and δ catalytic subunits of PP1 (Fig 3E), and the 128-kD band (Fig 3B) to PP1M (Fig 3E). Nonspecific binding of hsp90, PP1Cα, PP1Cδ, and PP1M to control immunoprecipitates with nonimmune rat IgG was not observed (Fig 3D and E).

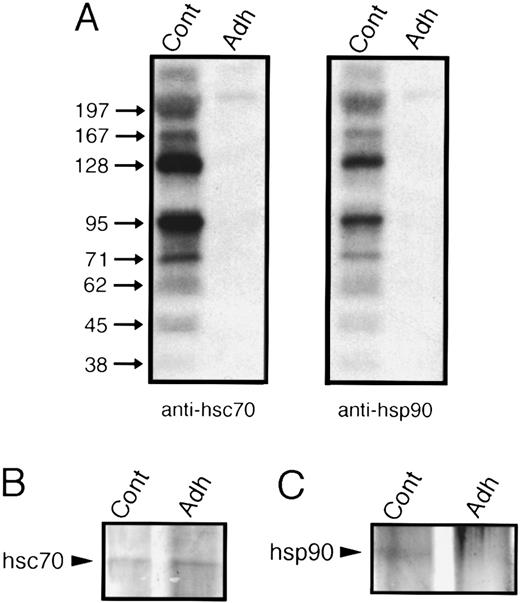

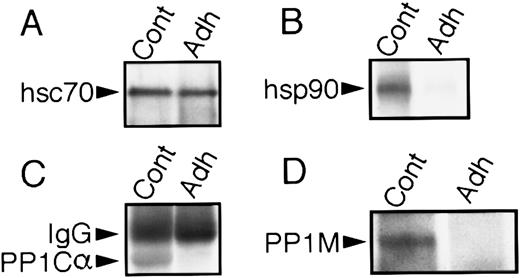

Dephosphorylation of hsc70 during platelet adhesion to collagen.We then assessed whether platelet adhesion to collagen influenced the phosphorylation state of the 67-71–kD protein, presumably hsc70. Lysates of 32P-labeled platelets from either control or adherent platelets were immunoprecipitated with anti-hsc70 MoAb. Because the pattern and extent of phosphorylation of hsc70 immunoprecipitates were very similar for effluent and resting platelets (data not shown), in most experiments we used resting (unstimulated) platelets as controls. Autoradiography of the hsc70 immunoprecipitates showed complete dephosphorylation of the 67-71–kD protein and dephosphorylation or dissociation of the other phosphoproteins after adhesion (Fig 4A, two left lanes). Both silver stain and immonoblots of immunoprecipitates with anti-hsc70 antibody showed similar amounts of 67-71–kD protein in control and adherent cells (Figs 4B and 5A, respectively). In sharp contrast to adhesion, thrombin-induced aggregation performed for the same length of time did not initiate dephosphorylation of platelet proteins (Fig 1). When hsc70 was immunoprecipitated from thrombin-aggregated 32P-labeled cells, it was even more highly phosphorylated after thrombin stimulation than in resting platelets and the complex remained intact (data not shown), indicating different signaling pathways induced by thrombin and collagen.

Platelet adhesion to collagen causes dephosphorylation of hsc70 and hsp90 phosphoprotein complexes. Immunoprecipitates (Ips) from lysates of 32P-labeled platelets were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE minigels. The gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography. Cont refers to Ips from resting platelets and Adh to Ips from platelets adherent to collagen. (A) The two left lanes are anti-hsc70 Ips using the antibody 1B5; the two right lanes are anti-hsp90 Ips using the antibody AC88. (B) Silver stain of hsc70 immunoprecipitates. (C) Silver stain of hsp90 immunoprecipitates. An autoradiogram and silver stain of the gels representative for four experiments are presented.

Platelet adhesion to collagen causes dephosphorylation of hsc70 and hsp90 phosphoprotein complexes. Immunoprecipitates (Ips) from lysates of 32P-labeled platelets were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE minigels. The gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography. Cont refers to Ips from resting platelets and Adh to Ips from platelets adherent to collagen. (A) The two left lanes are anti-hsc70 Ips using the antibody 1B5; the two right lanes are anti-hsp90 Ips using the antibody AC88. (B) Silver stain of hsc70 immunoprecipitates. (C) Silver stain of hsp90 immunoprecipitates. An autoradiogram and silver stain of the gels representative for four experiments are presented.

hsp90, PP1Cα, and PP1M are released from the hsc70 phosphoprotein complex during platelet adhesion to collagen. Anti-hsc70 immunoprecipitates from lysates of resting (Cont) and adherent (Adh) platelets were separated by SDS-PAGE minigels, and Western blots were performed with the appropriate antibodies as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Equal amounts of hsc70 were immunoprecipitated from resting and adherent platelets. (B) hsp90 dissociates from hsc70, (C) PP1Cα dissociates from hsc70, and (D) PP1M dissociates from hsc70 when platelets adhere to collagen.

hsp90, PP1Cα, and PP1M are released from the hsc70 phosphoprotein complex during platelet adhesion to collagen. Anti-hsc70 immunoprecipitates from lysates of resting (Cont) and adherent (Adh) platelets were separated by SDS-PAGE minigels, and Western blots were performed with the appropriate antibodies as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Equal amounts of hsc70 were immunoprecipitated from resting and adherent platelets. (B) hsp90 dissociates from hsc70, (C) PP1Cα dissociates from hsc70, and (D) PP1M dissociates from hsc70 when platelets adhere to collagen.

Adhesion-induced dissociation of hsc70/hsp90/PP1 complex.We subsequently assessed whether platelet adhesion to collagen influenced the association of the 67-71–kD protein with other proteins. To evaluate whether these proteins may have dissociated from the complex, immunoprecipitation experiments with the anti-hsc70 MoAb were performed on control and adherent platelets, followed by immunoblotting with anti-hsc70, anti-hsp90, anti-PP1Cα, and anti-PP1M. Immunoblotting with anti-hsc70 showed that comparable amounts of 67-71–kD protein were precipitated from the adherent and control platelets (Fig 5A). However, the 95-kD protein (hsp90; Fig 5B), PP1Cα (Fig 5C), and PP1M (Fig 5D) were no longer associated with the hsc70 complex, indicating that adhesion had caused their release.

Immunoprecipitation of platelet hsp90.hsp90 is a major phosphoprotein that can interact with various proteins such as actin, tubulin, calmodulin, steroid-hormone receptors, and a number of protein kinases.46 We therefore assessed the presence and phosphoprotein associations of hsp90 in unstimulated, 32P-labeled platelets by means of immunoblots and immunoprecipitations with both anti-hsp90 and control antibodies. We used the AC88 antibody that recognizes free hsp90 or hsp90 not complexed with steroid hormone receptors47 and that was previously used to immunoprecipitate proteins that react with antibodies against α and β tubulin.9 This antibody recognized a 95-kD phosphoprotein that migrated identically to purified bovine hsp90 (data not shown). Immunoprecipitations of control 32P-labeled platelets showed a pattern of coimmunoprecipitating phosphoproteins similar to that observed for hsc70 with the 1B5 antibody (Fig 4A, two right lanes). As observed before (Fig 3C), control nonimmune mouse IgG did not precipitate significant amounts of 32P-labeled platelet proteins.

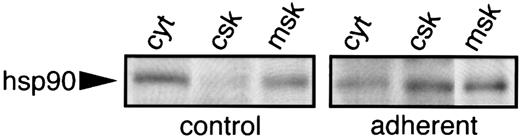

hsp90 is translocated to the cytoskeleton during adhesion.Autoradiograms of 32P-labeled hsp90 immunoprecipitates of adherent platelets showed a complete loss of radioactive phosphate (Fig 4A, two right lanes). However, in contrast to our observations for hsc70, the amount of hsp 90 immunoprecipitated with the AC88 MoAb in adherent cells was almost undetectable compared with control or nonadherent platelets as determined by silver stain of the hsp90 immunoprecipitates (Fig 4C). Because our methods involved preclearing platelet lysates by centrifugation at 15,000g for 10 minutes before incubation with precipitating antibody, the 95-kD protein could have been translocated to the platelet cytoskeleton and thus been cleared during the 15,000g centrifugation. To examine the subcellular localization of hsp90 in resting and adherent platelets, differential centrifugation methods30 were used with lysates of control and adherent cells to obtain the cytoskeleton (csk; 15,000g pellet), the membrane-skeleton (msk; 100,000g pellet), and solubilized cytosolic proteins (cyt; 100,000g supernatant). Western blot analysis with anti-hsp90 MoAb AC88 showed that the majority of hsp90 in resting platelets was present in solubilized cytosol and that trace quantities of hsp90 were detectable in the membrane-skeleton. After adhesion, the amount of hsp90 was greatly reduced in the cytosol of adherent platelets and more hsp90 became associated with the cytoskeleton and membrane-skeleton (Fig 6).

Translocation of hsp90 from the cytoplasm to the cytoskeleton and membrane skeleton during platelet adhesion to collagen. Resting and adherent platelets were solubilized in lysis buffer and cytoskeletal (csk), membrane-skeleton (msk), and cytosol (cyt) fractions were prepared by using differential centrifugation.30 The fractions were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The presence of hsp90 in each fraction was examined by Western blot analysis using the hsp90 antibody AC88. The location of hsp90 is indicated by the arrow. One of two similar experiments is shown.

Translocation of hsp90 from the cytoplasm to the cytoskeleton and membrane skeleton during platelet adhesion to collagen. Resting and adherent platelets were solubilized in lysis buffer and cytoskeletal (csk), membrane-skeleton (msk), and cytosol (cyt) fractions were prepared by using differential centrifugation.30 The fractions were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The presence of hsp90 in each fraction was examined by Western blot analysis using the hsp90 antibody AC88. The location of hsp90 is indicated by the arrow. One of two similar experiments is shown.

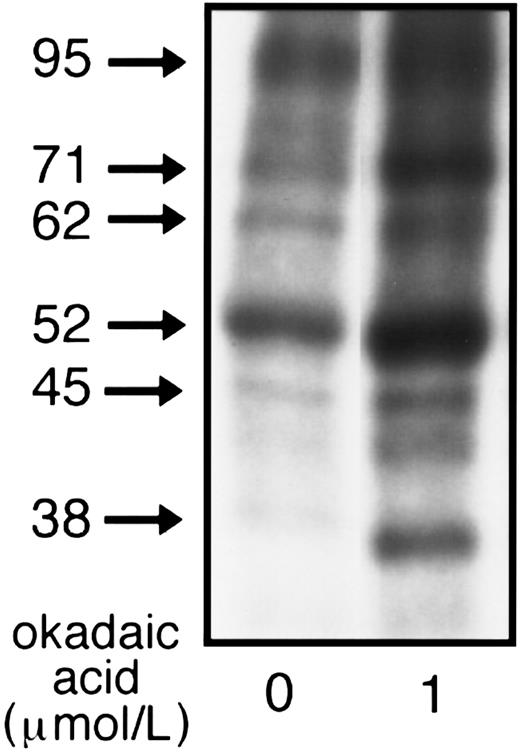

Effect of OA on hsc70 complex.Because OA blocked adhesion (Table 1) and is known to cause marked changes in protein phosphorylation of resting platelets,34 we also examined the effects of OA on the phosphorylation of the hsc70 protein complex. Immunoprecipitation with anti-hsc70 of 32P-labeled resting platelets showed that OA significantly increased 32P incorporation into hsc70 (p71) and hsp90 (p95) as well as into other unknown proteins that coimmunoprecipitated with hsc70, particularly p62, p52-50, p45, and p38 (Fig 7).

Effect of OA on phosphorylation of the hsc70 complex. 32P-labeled resting platelets (5 × 108 platelets/mL) preincubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with either 1 μmol/L OA (OA-treated) or with 0.1% DMSO (control) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-hsc70 MoAb. To avoid gel overexposure after OA treatment, only 25% of the total immunoprecipitated material from control and OA-treated platelets was applied to the 8% SDS-PAGE minigels, dried, and analyzed by autoradiography. One of five similar experiments is presented.

Effect of OA on phosphorylation of the hsc70 complex. 32P-labeled resting platelets (5 × 108 platelets/mL) preincubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with either 1 μmol/L OA (OA-treated) or with 0.1% DMSO (control) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-hsc70 MoAb. To avoid gel overexposure after OA treatment, only 25% of the total immunoprecipitated material from control and OA-treated platelets was applied to the 8% SDS-PAGE minigels, dried, and analyzed by autoradiography. One of five similar experiments is presented.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have shown that platelet adhesion to collagen under flow conditions induced distinct changes in protein phosphorylation compared with adhesion to the nonspecific substrate polylysine or to aggregation induced by thrombin. In particular, adhesion to collagen caused significant dephosphorylation of several protein bands, which were highly phosphorylated in resting platelets (Fig 1). We also observed that OA strongly inhibited adhesion. These new findings suggest that activation of serine/threonine protein phosphatases could be involved in the initiation of adhesion as well as occur as a result of adhesion. We have now found that resting platelets contain a phosphoprotein complex of hsc70 with hsp90, PP1Cα, PP1Cδ, PP1M, and 7 unidentified phosphoproteins. The association of hsc70 with these proteins was modified during α2β1 integrin-mediated adhesion to collagen such that hsc70 became dephosphorylated and hsc70-associated proteins were released from the complex. Stimulation with thrombin did not cause dephosphorylation of hsc70 and complex dissociation, showing that this behavior was specific for activation by collagen.

In addition to the dephosphorylation events noted above, adhesion to collagen caused phosphorylation of a 47-kD protein (p47, pleckstrin) indicating PKC activation.33 PKC activation also occurred in platelets stimulated by thrombin or in platelets adherent to polylysine (Fig 1). However, in contrast to thrombin-and polylysine-stimulated platelets, we observed minimal phosphorylation of a 20-kD protein (p20; Fig 1), which is a substrate for the Ca2+/calmodulin dependent myosin light-chain kinase,48 indicating that adhesion did not induce a significant increase in [Ca2+]i. This observation parallels other studies showing that either adhesion to collagen or stimulation with collagen in the presence of indomethacin causes only a small degree of phospholipase C activation and IP3 formation, without a corresponding increase in [Ca2+]i.49,50 In contrast, Smith et al51 found that direct activation by collagen involves an increase in platelet cytosolic free Ca2+ but also noted that this increase is not required for platelet adhesion to collagen. Poole and Watson52 observed an increase in cytosolic calcium in single human platelets adherent to collagen fibers by using dynamic fluorescence ratio imaging. Under the labeling conditions used in our studies, a 67-71–kD protein band was the most highly phosphorylated protein band in resting platelets, and adhesion to collagen was correlated with significant dephosphorylation of this band (Fig 1). This finding indicates that in unstimulated platelets these constitutively phosphorylated proteins have a potential role for initiating signaling and that there is a need to identify the proteins that are dephosphorylated to help establish the significance and mechanisms of activation of phosphatases during adhesion. Interestingly, a correlation has been described between aggregation induced by either phorbol myristate acetate or by U46619 and the dephosphorylation of a 68-kD protein band sensitive to OA.53

Treatment of platelets with 1 μmol/L OA, a potent inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A, increased the phosphorylation of several proteins, including the 67-71–kD protein band; in general, the increases were similar to changes reported previously.54 This finding parallels other results indicating that constitutive protein kinases and phosphatases are actively cycling and are responsible for the observed pattern of phosphorylation seen in unstimulated cells.34 Our observation that OA increased phosphorylation of the 67-71–kD band in resting cells suggests that OA-sensitive phosphatases are involved in dephosphorylating proteins in this band under basal conditions. It is also possible that the phosphorylation state is controlled by both OA-sensitive phosphatases and by unknown kinases. Inhibition of PP1 and/or PP2A by OA blocked adhesion (Table 1), indicating either a direct or indirect role for dephosphorylation in adhesion, and this corresponds to other studies with human B cells.18,19 Those platelets that actually managed to adhere still exhibited strong dephosphorylation of the 67-71–kD protein band. These OA-treated adherent platelets were concentrated such that the same amount of platelet protein was then added to each electrophoresis lane. This result could be interpreted that, under these conditions, the phosphatase(s) involved is insensitive to OA or that OA is poorly penetrant into platelets. Alternatively, a subpopulation of platelets insensitive to OA could exist. In this context, it is well known that a significant pool of platelets (15% to 20%) can adhere to collagen even in the presence of high levels of cAMP.27 The identity of the new small band just below the 67-kD band (Fig 2) is unknown. The importance of phosphatases in platelet activation has been suggested by the transient phosphorylation of proteins such as pleckstrin (p47) and myosin light chain (p20) that occurs after thrombin- or collagen-induced aggregation.34 In addition, prior studies with OA and calyculin A showed that, in thrombin-stimulated platelets, inhibition of PP1 and PP2A blocked aggregation, phosphatidyl inositol (PI) metabolism, Ca2+ entry, and secretion from dense granules.37 54-56 In all of these cases, the inhibition of protein phosphatases reversed the phosphorylation changes that occur during activation of feedback pathways involving protein kinase A and C. However, our understanding about signal transduction events during adhesion is still limited, including protein phosphorylation changes and how these relate to the establishment of stable irreversible adhesion.

The finding that hsc70 was present in the 67-kD protein band encouraged us to study the association of hsc70 with platelet phosphoprotein phosphatases. In many cell types, hsc70 and hsp 90 are the most abundant proteins in cytosol and both can exist as phosphoproteins.57,58 There is considerable evidence that these hsps are involved in regulating protein folding, serve as chaperones, and assist protein-protein interactions.10,11,45,46 There is some evidence that hsp70s can interact with protein phosphatases and alter their activities in vitro.44,59 We have now shown that resting platelets possess phosphorylated hsc70 that associated with a number of other proteins (Fig 3B), using immunoprecipitations with antibodies directed against hsc70, followed by immunobloting and autoradiography. Some of these proteins have been identified: hsp90, PP1Cα, PP1Cδ, and PP1M. The association of hsp70 with hsp90 has been previously described in other cell types such the human mammary tumor T47D cell line, the hepatoma cell line 1c1c7, and chicken oviduct,60-62 but not in human platelets. It is possible that the proteins described here could have become associated with hsc70 nonspecifically after platelet lysis. However, specific associations and interactions are likely, because a limited number of proteins coimmunoprecipitated with hsc70 in a highly reproducible manner, even using different antibodies. Whether these proteins interact directly with hsc70 or bind to one of the other proteins complexed with hsc70 requires further analysis. Recent reports support our new findings on the association of hsc70 with protein phosphatases. The 78-kD glucose-regulated protein, a member of the hsp70 family, has been shown to associate with the PP1γ2 catalytic subunit.44 In addition, purified hsp70 when added to rabbit reticulocyte lysates may activate phosphoprotein phosphatases.59 In the studies reported here, some of the proteins associated with hsc70 have been identified. Other proteins bound to hsc70 that were not detected by 32P-labeling may well exist. For example, tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins, nonphosphorylated proteins, or proteins only weakly bound to hsc70 that could have been washed off the immunoprecipitates, even by the low-salt conditions, were used.

Little is presently known about how collagen binding to the α2β1 integrin might initiate intracellular signaling. Keely and Parise63 found that the α2β1 integrin may be required as coreceptor for activation of pp72syk and subsequent phosphorylation of phospholipase C-γ2 in aggregating platelets stimulated with collagen fibers. In addition, GPVI appeared to be stongly involved in pp72syk activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase C-γ2, pp95vav, and of focal adhesion kinase, pp125FAK.25 We previously observed that adhesion caused rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of pp125FAK that was blocked by the anti-α2β1 antibody and associated with changes in cyclic nucleotides.27,29 In the present study, we have shown that adhesion to collagen was correlated with dephosphorylation of hsc70. Some of the proteins which coimmunoprecipitated with hsc70 in resting platelets, such as hsp90, PP1α, and PP1M were released from the phosphoprotein complex after adhesion and moved to new cellular compartments. For example, hsp90 was partially translocated to the cytoskeleton and to the membrane skeleton. The localization and phosphorylation changes of the other complex components after adhesion are currently under study. Recently, Uzawa et al64 reported the presence of a centrin/hsp70/hsp90 complex in CSF-arrested Xenopus oocytes that dissociates after treatments known to activate the oocyte for embryologic development. At the moment we do not know if or how the platelet complex may be associated with the α2β1 integrin or another collagen receptor. It has been recently shown that the α2β1 integrin can directly bind to actin65 that might thus form a bridge to heat-shock proteins and the collagen receptor. In addition, hsp70 may cross-link intracellular molecules to actin microfilaments3 and indirectly modulate adhesive receptors.

The 95-kD protein present in the phosphoprotein complex of resting platelets and sensitive to OA was shown to be hsp90 (Figs 1, 2, and 6). It may correspond to the unknown 90-kD protein whose phosphorylation was increased by OA and calyculin A and that correlated with dramatic changes in the morphology of resting platelets.66 This unknown 90-kD protein was shown to coimmunoprecipitate with tubulin. Previously, colocalization of hsp90 along tubulin-containing fibrillar structures was reported in epithelial cells.9 In addition, Fostinis et al67 showed colocalization of hsp90 with microtubules and the presence of hsp90 in the Triton X-100 insoluble cytoskeleton of a human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line. Thus, there is good evidence that hsp90 may associate with the cytoskeleton of cells, an association supported by our localization studies.

A number of platelet proteins become hyperphosphorylated in the presence of OA, in particular, a 50-kD protein whose phosphorylation correlates with inhibition of platelet function and that is markedly potentiated by prostacyclin.68 This 50-kD protein is also a major substrate for cyclic nucleotide-dependent kinases in platelets and is known as the VASP protein.69 We showed earlier that adhesion is blocked by both prostacyclin and sodium nitroprusside.27 In the present study, we found that platelet adhesion was inhibited by OA, correlating with enhanced phosphorylation of the 50- and 67-kD protein bands. OA also caused hyperphosphorylation of hsc70 and other complex components (Fig 7), such an unknown protein of molecular mass of 52-50 kD, which on one-dimensional SDS-PAGE ran similarly to phosphorylated VASP. This finding would fit in with the general theme that the 50-kD protein is VASP in its hyperphosphorylated state69 and is associated with inhibition of platelet function, plus the observation that the heat-shock protein complex is phosphorylated in the resting or inactive state of platelets (Fig 3). The theme that heat-shock protein complexes are phosphorylated in resting cells and are poised to initiate and regulate cellular signaling pathways has been developed by Rutherford and Zucker.46

We wish to emphasize that we do not have direct evidence that the 67-71–kD protein band dephosphorylated during adhesion (Fig 1) and that migrates at the same molecular weight of hsc70 in whole-cell lysates is the same hsc70 that was immunoprecipitated with the anti-hsc70 antibody and shown to be dephosphorylated in immunoprecipitates of adherent cells. It is possible that hsc70 itself was not phosphorylated in unstimulated platelets, but rather was associated with another phosphoprotein(s) of similar molecular weight that was immunoprecipitated with the anti-hsc70 MoAb. Although the present study shows an association of hsc70 with hsp90, PP1, and other unidentified phosphoproteins in resting platelets, the functional significance of these interactions is still unknown. The interaction of hsc70, hsp90, and PP1 could have little relevance in platelets, possibly due to the high intracellular levels of these proteins that may lead to nonspecific associations. However, the finding that α2β1 integrin-mediated adhesion to collagen was always correlated with complex disassembly and dephosphorylation of some components supports the thesis that the complex plays an important role in cell adhesion. Recent studies describing tyrosine phosphorylation of hsc70 in response to ligation of the T-cell antigen receptors13 and of hsp75 in response to oxidative stress14 indicate that this modification might regulate hsp function and thus cell adhesion. There is strong evidence linking hsp90 and hsp70 to the signaling functions of the glucocorticoid receptor complex70 and hsp90 is known to form complexes with a number of signaling molecules, including protein kinases, such as pp60v-src and Raf.46 Our findings now show that heat-shock proteins possess the ability to bind other critical signaling enzymes, such as protein phosphatases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank J. Lawrence and D. Hartshorne for providing antibodies; D. Brautigan and A. DePaoli-Roach for advice about phosphatase antibodies; T. Haystead, T. Sturgill, G. Balian, and J. Hockensmith for critical review of the manuscript and helpful discussions; and V. Gordon and L. Beggerly for technical assistance.

Research supported by the Carman Trust and initially by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant No. HL-27014. The mass spectrometry studies were supported by the NIH Grant No. GM-37537.

Presented in part in abstract form at the American Society for Cell Biology Thirty-fifth Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, December 1995 (Mol Biol Cell 6:384a, 1995 [suppl]).

Address reprint requests to Renata Polanowska-Grabowska, PhD, Department of Biochemistry, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal