Abstract

Recent data suggest that mast cells (MC) are involved in the regulation of leukocyte accumulation in inflammatory reactions. In this study, expression of leukocyte-chemotactic peptides (chemokines) in purified human lung MC (n = 16) and a human mast cell line, HMC-1, was analyzed. Northern blotting and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showed baseline expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 mRNA in unstimulated MC. Exposure of MC to recombinant stem cell factor (rhSCF, 100 ng/mL) or anti-IgE (10 μg/mL) was followed by a substantial increase in expression of MCP-1 mRNA. Neither unstimulated nor stem cell factor (SCF )-stimulated lung MC expressed transcripts for interleukin-8 (IL-8), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, or RANTES by Northern blotting. The mast cell line HMC-1, which contains a mutated and intrinsically activated SCF-receptor, was found to express high levels of MCP-1 mRNA in a constitutive manner. Exposure of HMC-1 cells to rhSCF resulted in upregulation of MCP-1 mRNA expression, and de novo expression of MIP-1β mRNA. The SCF-induced upregulation of MCP-1 mRNA in lung MC and HMC-1 was accompanied by an increase in immunologically detectable MCP-1 in cell supernatants (sup) (lung MC [<98%], control medium, 1 hour: 159 ± 27 v SCF, 100 ng/mL, 1 hour: 398 ± 46 pg/mL/106 cells; HMC-1: control, 1 hour: 894 ± 116 v SCF, 1 hour: 1,536 ± 265 pg/mL/106). IgE-dependent activation was also followed by MCP-1 release from MC. MC-sup and HMC-1–sup induced chemotaxis in blood monocytes (Mo) (control: 100% ± 12% v 2-hour–MC-sup: 463% ± 38% v HMC-1–sup: 532% ± 12%), and a monoclonal antibody (MoAb) to MCP-1 (but not MoAb to IL-8) inhibited Mo-chemotaxis induced by MC-sup or HMC-1–sup (39% to 55% inhibition, P < .05). In summary, our study identifies MCP-1 as the predominant CC-chemokine produced and released in human lung MC. MCP-1 may be a crucial mediator in inflammatory reactions associated with MC activation and accumulation of MCP-1–responsive leukocytes.

CHEMOKINES are structurally related proinflammatory peptides inducing mediator secretion and chemotaxis in leukocytes.1-5 Based on the spacing of the first two cysteine residues, three major groups of chemokines (CC, CXC, and C) have to be distinguished.1-3 The CC-chemokine family includes MCP-1 through 4, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES. Members of the CXC-chemokines are interleukin-8 (IL-8), growth-related protein (GRO), and interferon-γ–inducible protein (IP-10). A well-established concept is that CC-chemokines primarily act on monocytes, basophils, eosinophils, and T lymphocytes, whereas CXC-chemokines primarily exert their effects on neutrophil granulocytes.1-3 6-9

Chemokines are produced in distinct cells such as macrophages, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, or lymphocytes.10-15 In most cell systems, the chemokines are produced and secreted in huge amounts on cell activation, but not in resting cells.10-15 Correspondingly, high levels of chemokines are detectable in vivo in inflammatory reactions such as bacterial sepsis16 or autoimmune reactions.17 Also, chemokines are detectable in atherosclerotic lesions,18,19 and patients with bronchial asthma or other allergic disorders.20-24 Thus, under a variety of pathologic conditions, the chemokines are considered to be responsible for the migration, accumulation, and activation of leukocytes.1-5

Mast cells (MC) are multifunctional immune cells involved in diverse inflammatory processes.25-27 These cells store a number of vasoactive and proinflammatory mediator molecules and are able to release their mediators in response to cell activation by a specific antigen or by other stimuli.28-30 Recently, MC have been implicated in diverse pathophysiologic reactions related to endothelial cell activation and leukocyte function.25,31-35 For example, under certain conditions, mast cells and their products mediate the rapid transmigration of leukocytes through vascular endothelium and the consecutive accumulation of leukocytes in experimental animals.33-35 Such MC-dependent events are thought to be triggered by certain biologically active substances. Besides histamine, which can induce selectin-expression on endothelial cells, one of the important MC mediators appears to be tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF -α).31-35

More recent studies suggest that mast cells, in addition to their ability to produce TNF, are a source of multiple cytokines.36-39 Thus, murine mast cells produce and release a number of interleukins and other polypeptide cytokines such as granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ), IL-3, or IL-1. In addition, murine MC, after stimulation with IgE-dependent or other stimuli, can produce multiple chemotactic peptides including MIP-1α, MIP-1β, or MCP-1.38 However, little is known so far about the ability of human MC to produce and release chemokines. In one study, human skin MC have been described as a potential source of the CXC chemokine IL-8.39 The aims of the present study were to evaluate whether human lung MC are capable of producing chemokines, and to identify regulators of synthesis and secretion of chemokines in human MC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents, antibodies, and buffers. Recombinant human (rh) stem cell factor (SCF ) and rhMCP-1 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1) were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Collagenase type II was purchased from Sebak Co (Suben, Austria). Toluidine blue, hydrocortisone, and collagenase type IA were from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO). RPMI 1640 medium, gentamycin, amphotericin B, and fetal calf serum (FCS) were purchased from Sera Lab (Crawley Down, UK) and Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM), glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from GIBCO Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). Endothelial cell basal medium (EBM) and recombinant human endothelial cell growth factor (ECGF ) were from PromoCell Co (Heidelberg, Germany). The neutralizing monoclonal mouse antihuman MCP-1 antibodies (MoAb) S101 (IgG1 subclass) and S14 (IgG1) were obtained from Anogen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), and the neutralizing mouse antihuman IL-8 MoAb DM/C7 (IgG1) from Genzyme (Cambridge, MA). The monoclonal anti-IgE antibody E-124-2-8 (Dε2) was purchased from Immunotech (Marseille, France) and monoclonal IgE from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). The anti–c-kit MoAb YB5.B8 (IgG1) was kindly provided by L.K. Ashman (University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia). One liter Ca2+/Mg2+ free Tyrode's buffer contained 0.2 g KCl, 0.05 g NaH2PO4 .H2O, 0.8 g NaCl, and 1 g glucose. All oligonucleotide probes and primer pairs (for Northern blotting and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were from MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany).

Cell lines. The human mast cell line HMC-140 was established from a patient suffering from mast cell leukemia and kindly provided by J.H. Butterfield (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). HMC-1 cells were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics at 37°C and 5% CO2 . The human basophil precursor cell line KU-81241 was kindly provided by K. Kishi (Nijgata University, Nijgata, Japan) and kept in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FCS. Other myeloid cell lines used in this study were U937, HL-60, and KG-1; these cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 with 10% FCS.

Purification of primary MC. Lung tissue was obtained at surgery (lobectomy) from 16 patients suffering from bronchiogenic carcinoma after informed consent was given. Lung tissue was prepared following the method described by Schulman et al.42 In brief, tissue was placed in Tyrode's buffer immediately after resection, chopped into small fragments, and washed extensively in Mg2+/Ca2+-free Tyrode's buffer. Then, tissue fragments were incubated in collagenase type II (2 mg/mL) at 37°C for 1 to 3 hours. Thereafter, dispersed cells were recovered by filtration through Nytex cloth and washed three times in Tyrode's buffer. Cells were then examined for the percentage of MC by toluidine blue or Giemsa staining. MC-containing cell suspensions were further enriched for MC by current counter flow centrifugation (elutriation) as described by Willheim et al.43 In brief, cells were loaded at a flow rate of 12 mL per minute into a Beckman elutriator equipped with a JE-6B rotor (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA) (1,825 rpm, room temperature). Fractions were recovered at increasing flow rates (14, 18, 20, and 30 mL per minute). A selection was performed based on the content of MC. In one donor, two fractions containing more than 90% MC (total number of cells: 6 × 107) were recovered. These MC were cultured overnight (37°C, 5% CO2 ) and were then exposed to rhSCF, 100 ng/mL (3 × 107 cells) or control medium (3 × 107) at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 2 hours. Next, supernatants were recovered by aspiration and MC washed in RNase free NaCl (0.9%) and subjected to RNA preparation and Northern blot experiments. In the other donors (n = 15), the elutriated MC were further enriched by cell sorting using anti–c-kit MoAb YB5.B8 as described.43 In brief, MC were exposed to MoAb YB5.B8, washed, and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat antimouse antibody. MC were sorted as c-kit++ cells and were more than 98% pure as assessed by Giemsa staining (500 cells counted). Six of the 15 MC preparations (each >98% pure) were pooled (total number of cells, 7 × 106) for Northern blotting. Four MC preparations were used for RT-PCR analysis and five MC preparations for MCP-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measurements. In selected experiments, some of the purified MC samples (n = 3) were used for cytospin preparation and in situ staining experiments.

Stimulation of MC with rhSCF or anti-IgE. Primary lung MC being 91% pure, were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS in the presence or absence of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) for 2 hours. Ultrapure lung MC (>98%) were cultured in the presence of control medium or rhSCF (100 ng/mL) for 2 or 8 hours. In case of IgE-dependent activation, MC (n = 3) were first incubated with IgE (10 μg/mL, 3 hours), washed, and then exposed to either control medium, anti-IgE MoAb E-124-2-8 (10, 1, and 0.1 μg/mL) or a combination of anti-IgE (10 μg/mL) and SCF (100 ng/mL) at 37°C for 2 and 8 hours. After incubation with agonists, cells were centrifuged and the cell-free supernatants recovered. Cells were analyzed for MCP-1 mRNA (RT-PCR or Northern blotting) or cellular MCP-1 (ELISA) and the supernatants for the presence of released MCP-1 (ELISA). HMC-1 cells were exposed to (1) rhSCF (1 to 200 ng/mL), (2) a mixture of rhSCF and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 50 ng/mL), or (3) control medium (IMDM, 10% FCS) for 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, and 24 hours. All incubations were performed at 37°C in 5%CO2 .

Northern blot analysis. For Northern blot analysis, total RNA was extracted from cells by the guanidinium isothiocyanate/cesium chloride method described by Chirgwin et al.44 Northern blot analyses were performed using purified lung MC and HMC-1 as described previously.45 In brief, 10 μg RNA were size-fractionated on 1.2% agarose gels and transferred to synthetic membranes (Hybond N; Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK) with 20× SSC (1× SSC consists of 150 mmol/L NaCl and 15 mmol/L sodium citrate, pH 7.0) overnight, cross-linked to membranes by ultraviolet (UV) irradiation (UV Stratalinker 1800, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and then prehybridized at 65°C for 4 hours in 5× SSC, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10× Denhardt‘s solution (DhS) (1× DhS consists of 0.02% bovine serum albumin, 0.02% polyvinyl pyrolidone, and 0.02% Ficoll), 10% dextran sulfate, 20 mmol/L sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), sonicated salmon sperm DNA (100 μg/mL), and poly(A+) (100 μg/mL). Hybridization was performed with 32P-labeled synthetic oligonucleotide probes (Table 1) for 16 hours at 65°C in prehybridization buffer. Probes were labeled by terminal nucleotidyltransferase and α-32P 2′-Deoxy-adenosine-5′-triphosphate (dATP). Blots were washed once in 3× SSC, 5% SDS, 10× DhS, and 20 mmol/L sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, for 30 minutes at 65°C, and once in 1× SSC, 1% SDS for 30 minutes at 65°C. Bound radioactivity was visualized by exposure to XAR-5 films at −70°C using intensifying screens (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Oligonucleotide Sequences

| Gene . | n-mer . | Oligonucleotide Sequence . | Reference No. . |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | 34 | 5′-GGCTGGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAACATGATCTGG-3′ | 47 |

| c-kit | 34 | 5′-CCTTACATTCAACCGTGCCATTGTGCTTGAATGC-3′ | 66 |

| SCF | 35 | 5′-GCTGTCTGACAATTGTACTACCATCTCGCTTATCC-3′ | 67 |

| MCP-1 | 27 | 5′-GGGTTTGCTTGTCCAGGTGGTCCATGG-3′ | 13 |

| MIP-1α | 31 | 5′-CGTGTCAGCAGCAAGTGATGCAGAGAACTGG-3′ | 68 |

| MIP-1β | 28 | 5′-GGTCTGAGCCCATTGGTGCTGAGAGTGC-3′ | 68 |

| IL-8 | 27 | 5′-GGGGTGGAAAGGTTTGGAGTATGTCTT-3′ | 69 |

| RANTES | 31 | 5′-CCACTGGTGTAGAAATACTCCTTGATGTGGG-3′ | 70 |

| Gene . | n-mer . | Oligonucleotide Sequence . | Reference No. . |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | 34 | 5′-GGCTGGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAACATGATCTGG-3′ | 47 |

| c-kit | 34 | 5′-CCTTACATTCAACCGTGCCATTGTGCTTGAATGC-3′ | 66 |

| SCF | 35 | 5′-GCTGTCTGACAATTGTACTACCATCTCGCTTATCC-3′ | 67 |

| MCP-1 | 27 | 5′-GGGTTTGCTTGTCCAGGTGGTCCATGG-3′ | 13 |

| MIP-1α | 31 | 5′-CGTGTCAGCAGCAAGTGATGCAGAGAACTGG-3′ | 68 |

| MIP-1β | 28 | 5′-GGTCTGAGCCCATTGGTGCTGAGAGTGC-3′ | 68 |

| IL-8 | 27 | 5′-GGGGTGGAAAGGTTTGGAGTATGTCTT-3′ | 69 |

| RANTES | 31 | 5′-CCACTGGTGTAGAAATACTCCTTGATGTGGG-3′ | 70 |

RT-PCR analysis. Total RNA was isolated from a known number of (>98% pure) MC (30,000) using a modified guanidinium isothiocyanate-acid phenol extraction procedure (RNAzol B method, Biotecx Laboratories Inc, Houston, TX) as described.43 Cell pellets were resuspended in 0.8 mL of RNAzol B and then exposed to chloroform (80 μL). Samples were shaked vigorously and stored at 4°C for 5 minutes. After centrifugation at 12,000g (4°C, 15 minutes), the upper aqueous phase was collected. A total of 6 μg of carrier RNA (yeast tRNA, stored as 4 mg/mL solution in RNase free water) were added before precipitating RNA with 0.4 mL of isopropanol overnight at −20°C. Precipitated RNA was centrifuged for 15 minutes at 12,000g (4°C). The supernatants were then removed and the RNA pellet washed once in 75% ethanol. Finally, the pellet was dissolved in RNase-free water and stored in liquid nitrogen.

cDNA synthesis was performed using a single-stranded cDNA synthesis kit (First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Pharmacia Biotech, Brussels, Belgium) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, total RNA dissolved in 20 μL RNase-free water was initially heated to 65°C for 10 minutes, quick-chilled on ice, and then incubated with 11 μL Bulk First-Strand Reaction Mix (Cloned, FPLCpure Murine Reverse Transcriptase, RNAguard, RNase/DNase-Free BSA, 1.8 mmol/L each dATP, 2′-Deoxy-cytidine-5′-triphosphate [dCTP], 2′-Deoxy-guanosine-5′-triphosphate [dGTP], and 2′-Deoxy-thymidine-5′-triphosphate [dTTP] in aqueous buffer), 1 μL dithiothreitol (DTT) solution (200 mmol/L aqueous solution), 1 μL pd(N)6 primer (random hexadeoxynucleotides at 0.2 μg/mL in aqueous solution) at 37°C for 1 hour. The reaction was terminated by heating to 90°C for 5 minutes. Samples were chilled on ice immediately and stored at −20°C for subsequent analysis. Aliquots of the cDNA products, 3 μL for the constitutively expressed β-actin gene and 15 μL for the MCP-1 gene were used for RT-PCR in a final volume of 100 μL containing 1× PCR buffer (Perkin Elmer Cetus, Emeryville, CA), 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer Cetus), and 25 μmol/L of both the upstream and the downstream primers specific for the MCP-1 gene (primer sequences were selected in light of the known homology of MCP-1/-2/-3 genes, no sequence homology of the primer pair used with gene sequences in MCP-2 and -3 was found) (5′MCP-1 [26-mer]: 5′-CATGAAAGTCTCTCTGCCGCCCTTCT-3′ and 3′MCP-1 [24-mer]: 5′-AGTTA GCTGCAGATTCTTGGGTTG-3′, see Morita et al46 ) and for the human β-actin gene (5′β-actin [20-mer]: 5′-AGGCCGGCTTCGCGGGCGAC-3′; 3′β-actin [21-mer]: 5′-CTCGGGAGCCACACGCAGCTC-3′, Ponte et al47 ). A master mix of PCR components was made up for each set of reactions before addition of the cDNA templates. Samples were amplified by 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 minute, 55°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute after an initial denaturation step (95°C, 2 minutes). An aliquot of each reaction mixture was subjected to electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer. PCR products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining and photographed.

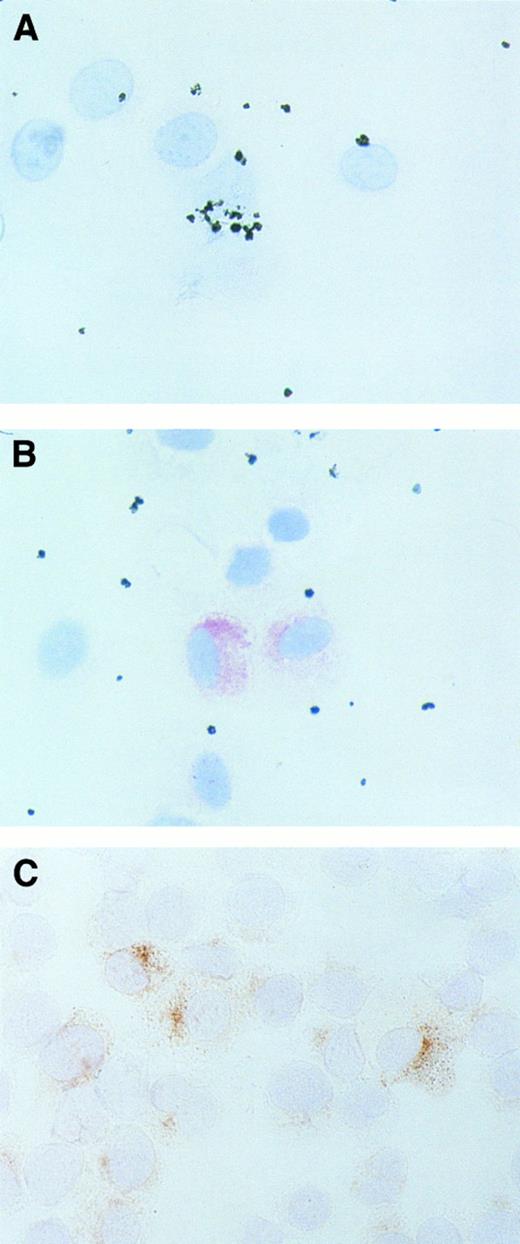

Immunohistochemistry of isolated MC. For evaluation of MCP-1 expression in single MC, purified lung MC (n = 3) and HMC-1 were suspended and exposed to rhSCF or control medium for 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 hours. Cells were then spun on cytospin slides and fixed in acetone. Immunohistochemistry was performed essentially as described48 using the antihuman MCP-1 MoAb S101 and the antitryptase MoAb G3 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). After washing the slides in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at pH 7.6, nonspecific binding was blocked with TBS and 1% horse serum (Vector, Burlingame, CA). The MoAbs S101 (anti–MCP-1) and G3 (antitryptase) were diluted in TBS (S101, 1:50 and G3, 1:1000), 1% horse serum and applied for 1 hour. Then, slides were washed and incubated with a biotinylated horse antimouse IgG (Vector) and streptavidin-alkaline–phosphatase complexes (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) or streptavidin-peroxidase complexes for 30 minutes. 3-Amino-9-ethyl carbazole (AEC) was used as substrate in peroxidase stains and neofuchsin (Dako) was used as chromogen in alkaline phosphatase staining experiments. Slides were counter-stained in Gill's hematoxylin. Control slides were similarly treated, with the primary antibody being omitted or by using isotype-matched control MoAbs.

Purification of blood monocytes (Mo). Human Mo were isolated from eight healthy volunteers by a one-step Percoll gradient protocol as described previously.49 In brief, mononuclear cells (MNC) were obtained from whole blood (80 to 100 mL) by Ficoll (Sebak, Suben, Austria) gradient centrifugation (500g, 30 minutes). Isolated MNC were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 150g to remove platelets and resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FCS. The MNC (30 mL, 1 to 2 × 106 cells/mL) were then layered over an iso-osmotic 46%-Percoll solution (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) containing 5% FCS (15 mL). After centrifugation (550g ) at room temperature for 30 minutes, the Mo-rich fraction was recovered from the interface, washed in PBS, and resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium. The resuspended Mo fractions were then checked for the percentage of Mo (by Giemsa staining) and for cell viability by trypan blue exclusion. Pure Mo were used for chemotaxis experiments immediately after isolation. Mo purity was more than 80% in all experiments and cell viability more than 90% in each case.

Mo-chemotaxis assay. Mo-chemotaxis was quantitated using a 24-well double-chamber chemotaxis assay. Chemotaxis experiments were performed essentially as described.50 In brief, Mo were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium and adjusted to a final cell concentration of 3 × 106 cells/mL. Chemotactic factors (various concentrations of rhMCP-1, or FMLP, 10−7 mol/L), MC supernatants (HMC-1 or purified, 91% pure lung MC, various dilutions), or control medium were placed into the lower chambers. In blocking experiments, MCP-1 and MC supernatants were incubated with anti–MCP-1 MoAbs S101 (10 μg/mL), S14 (10 μg/mL), or anti–IL-8 MoAb DM/C7 (10 μg/mL) for 1 hour before being placed into chemotaxis chambers. After agonists had been placed in the lower chambers, microporous filter-membranes (0.6 cm2; pore size, 3.0 μm, Cyclopore, Aalst, Belgium) were inserted. Thereafter, Mo were placed in the upper chambers and incubated for 3 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2 . To discriminate between chemotaxis and nondirected migration (chemokinesis) of Mo, checkerboard analyses were performed. In these experiments, Mo were placed in the upper chambers and various concentrations of rhMCP-1 (1 to 10 ng/mL) or various dilutions of HMC-1 supernatants (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%) were added into either the upper or lower wells or into both. After 3 hours, membranes were detached and removed together with nontransmigrated Mo. The migrated Mo in the lower chambers were incubated with the fluorescence dye Calcein AM (5 mmol/l, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Then, labeled Mo were measured in a multiplate reader (Biosearch, Hamburg, Germany) and the number of migrated Mo calculated by the calculation program delivered by the manufacturers.

Measurement of chemokines by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Expression and release of chemokines in primary lung MC and HMC-1 cells was quantified by ELISA. Commercial ELISA assays detecting MCP-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), IL-8 (R&D), MIP-1α (R&D), MIP-1β (R&D), or RANTES (R&D) were applied. The detection limits were as follows: MCP-1, 5 pg/mL; MIP-1α, 7 pg/mL; MIP-1β, 11 pg/mL; IL-8, 10 pg/mL; and RANTES, 5 pg/mL. No cross-reactivities with other chemokines (notably MCP-2 and MCP-3), cytokines (TNF, IL-1 through IL-15, GM/G/M-CSF ), histamine, tryptase, or heparin were detectable in the ELISA assays.

Isolation and culture of endothelial cells and blood eosinophils. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated from umbilical veins (n = 3) according to standard techniques using collagenase. Umbilical veins were obtained at birth after informed consent had been given by mothers. HUVEC were isolated using collagenase type IA, and cultured in EBM containing 10% heat-inactivated (56°C, 30 minutes) FCS, ECGF (10 ng/mL), hydrocortisone (1 μg/mL), and antibiotics at 37°C in 5% CO2 . Isolated HUVEC were cultured in fibronectin-coated 35-mm plastic petri-dishes (Costar, Cambridge, MA). Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of three patients suffering from the hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) after informed consent was obtained. Eosinophils were enriched from whole blood by fractionation, using 1.1% dextran T 70 and 0.008 mol/L EDTA for 90 minutes at room temperature. Cells of the granulocyte-rich upper layer were washed twice in NaCl and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS. The resuspended granulocytes were then checked for the percentage of eosinophils by Giemsa staining and for cell viability by trypan blue exclusion. Eosinophil purity was more than 85% in all three donors and cell viability more than 90%. The cells were cultured at 37°C/5% CO2 for 2 hours.

Statistical analysis. Statistical significance was checked by appropriate tests including the paired Student's t-test. The results were considered to be significant when the P value was <.05.

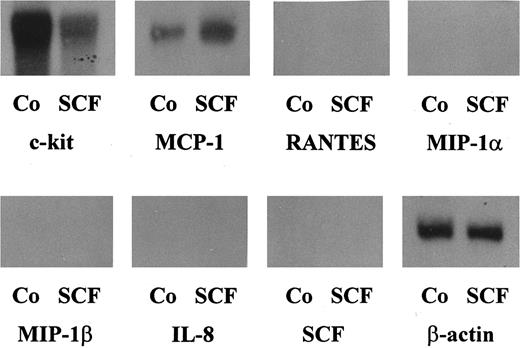

Northern blot analysis of purified human lung MC. Human lung MC (purity, 91%) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS in the presence of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) or control medium (Co) for 2 hours. Thereafter, cells were harvested and the extracted mRNA hybridized with oligo-nucleotide probes specific for MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IL-8, SCF or β-actin (as indicated). After each hybridization, blots were stripped. Unstimulated primary lung MC were found to express baseline levels of MCP-1 mRNA. However, incubation of MC with rhSCF resulted in a substantial increase in expression of MCP-1 mRNA (densitometry: control, 100%; rhSCF, 334%). Neither untreated nor SCF-treated MC expressed detectable amounts of transcripts specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, or IL-8.

Northern blot analysis of purified human lung MC. Human lung MC (purity, 91%) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS in the presence of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) or control medium (Co) for 2 hours. Thereafter, cells were harvested and the extracted mRNA hybridized with oligo-nucleotide probes specific for MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IL-8, SCF or β-actin (as indicated). After each hybridization, blots were stripped. Unstimulated primary lung MC were found to express baseline levels of MCP-1 mRNA. However, incubation of MC with rhSCF resulted in a substantial increase in expression of MCP-1 mRNA (densitometry: control, 100%; rhSCF, 334%). Neither untreated nor SCF-treated MC expressed detectable amounts of transcripts specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, or IL-8.

RT-PCR analysis of human MC. RT-PCR analyses were performed on highly purified lung MC (purity, <98%) ([A], lanes 1 through 8; [B], all lanes) and the mast cell line HMC-1 ([A], lanes 9 and 10) using primers specific for MCP-1 and β-actin. (A) Shows the effect of SCF on MCP-1 mRNA expression: primary MC were exposed to rhSCF or control medium for 2 or 8 hours. mRNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis was done as described in the text. Exposure of lung MC to rhSCF led to an increase in expression of MCP-1 mRNA after 2 hours (lane 4) and 8 hours (lane 8), compared with control (2 hours, lane 2; and after 8 hours, lane 6). RT-PCR analysis of lung MC was controlled by using primers specific for β-actin (lane 1, control medium, 2 hours; lane 3, rhSCF, 2 hours; lane 5, control medium, 8 hours; lane 7, rhSCF, 8 hours). HMC-1 cells expressed significant amounts of MCP-1 mRNA (lane 10) in a constitutive manner. Lane 9, β-actin control of HMC-1 cells. (B) Shows the effect of anti-IgE and anti-IgE + SCF on MC. Highly purified lung MC (<98%) were exposed to control medium (lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8), anti-IgE MoAb E-124-2-8, 10 μg/mL (lanes 3, 4, 9, and 10), and rhSCF, 100 ng/mL plus anti-IgE, 10 μg/mL (lanes 5, 6, 11, and 12) for 2 hours (lanes 1 through 6) or 8 hours (lanes 7 through 12) at 37°C. RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for MCP-1 (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12) and β-actin (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11). As visible, anti-IgE and anti-IgE + SCF augmented MCP-1 mRNA expression in lung MC.

RT-PCR analysis of human MC. RT-PCR analyses were performed on highly purified lung MC (purity, <98%) ([A], lanes 1 through 8; [B], all lanes) and the mast cell line HMC-1 ([A], lanes 9 and 10) using primers specific for MCP-1 and β-actin. (A) Shows the effect of SCF on MCP-1 mRNA expression: primary MC were exposed to rhSCF or control medium for 2 or 8 hours. mRNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis was done as described in the text. Exposure of lung MC to rhSCF led to an increase in expression of MCP-1 mRNA after 2 hours (lane 4) and 8 hours (lane 8), compared with control (2 hours, lane 2; and after 8 hours, lane 6). RT-PCR analysis of lung MC was controlled by using primers specific for β-actin (lane 1, control medium, 2 hours; lane 3, rhSCF, 2 hours; lane 5, control medium, 8 hours; lane 7, rhSCF, 8 hours). HMC-1 cells expressed significant amounts of MCP-1 mRNA (lane 10) in a constitutive manner. Lane 9, β-actin control of HMC-1 cells. (B) Shows the effect of anti-IgE and anti-IgE + SCF on MC. Highly purified lung MC (<98%) were exposed to control medium (lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8), anti-IgE MoAb E-124-2-8, 10 μg/mL (lanes 3, 4, 9, and 10), and rhSCF, 100 ng/mL plus anti-IgE, 10 μg/mL (lanes 5, 6, 11, and 12) for 2 hours (lanes 1 through 6) or 8 hours (lanes 7 through 12) at 37°C. RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for MCP-1 (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12) and β-actin (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11). As visible, anti-IgE and anti-IgE + SCF augmented MCP-1 mRNA expression in lung MC.

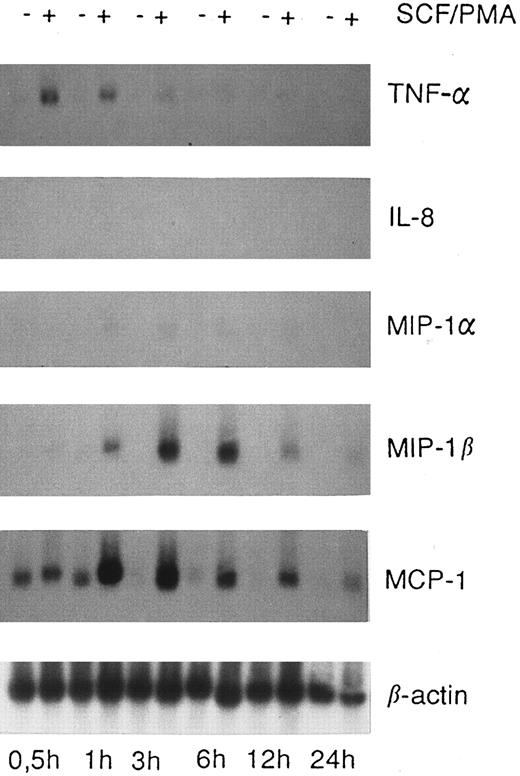

Expression of chemokine mRNA in HMC-1 cells. HMC-1 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of a mixture of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) and PMA (50 ng/mL) for various time periods as indicated. Thereafter, the cells were harvested and Northern blot analysis performed as described in the text. Unstimulated HMC-1 cells expressed MCP-1 mRNA, but no detectable amounts of mRNA specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, or IL-8. Stimulation of HMC-1 cells with rhSCF and PMA lead to a substantial increase in expression of MCP-1 and MIP-1β mRNA and minimal expression of MIP-1α mRNA, whereas transcripts for IL-8 were not detectable. Incubation of HMC-1 cells with rhSCF alone (without PMA) was also followed by an increase in MCP-1 mRNA expression, with a similar increase in mRNA when compared with cells exposed to rhSCF + PMA (not shown).

Expression of chemokine mRNA in HMC-1 cells. HMC-1 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of a mixture of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) and PMA (50 ng/mL) for various time periods as indicated. Thereafter, the cells were harvested and Northern blot analysis performed as described in the text. Unstimulated HMC-1 cells expressed MCP-1 mRNA, but no detectable amounts of mRNA specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, or IL-8. Stimulation of HMC-1 cells with rhSCF and PMA lead to a substantial increase in expression of MCP-1 and MIP-1β mRNA and minimal expression of MIP-1α mRNA, whereas transcripts for IL-8 were not detectable. Incubation of HMC-1 cells with rhSCF alone (without PMA) was also followed by an increase in MCP-1 mRNA expression, with a similar increase in mRNA when compared with cells exposed to rhSCF + PMA (not shown).

IgE-Mediated Release of MCP-1 From Isolated Lung MC

| Challenge . | MCP-1, pg per mL supernatant (106 cells per mL) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Donor 1 (%) . | Donor 2 (%) . | Donor 3 (%) . | Mean ± SD (%) . |

| Control buffer | 155.8 (100) | 162.8 (100) | 288.3 (100) | 202.3 ± 21.0 (100) |

| Anti-IgE, 10 μg/mL* | 358.8 (230) | 771.5 (474) | 529.5 (184) | 553.3 ± 210.6* (274) |

| Anti-IgE, 1 μg/mL | 210.8 (135) | 375.1 (230) | 348.5 (121) | 311.5 ± 116.2 (154) |

| Anti-IgE, 0.1 μg/mL | 140.2 (90) | 212.6 (131) | 280.0 (97) | 210.9 ± 34.0 (104) |

| Challenge . | MCP-1, pg per mL supernatant (106 cells per mL) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Donor 1 (%) . | Donor 2 (%) . | Donor 3 (%) . | Mean ± SD (%) . |

| Control buffer | 155.8 (100) | 162.8 (100) | 288.3 (100) | 202.3 ± 21.0 (100) |

| Anti-IgE, 10 μg/mL* | 358.8 (230) | 771.5 (474) | 529.5 (184) | 553.3 ± 210.6* (274) |

| Anti-IgE, 1 μg/mL | 210.8 (135) | 375.1 (230) | 348.5 (121) | 311.5 ± 116.2 (154) |

| Anti-IgE, 0.1 μg/mL | 140.2 (90) | 212.6 (131) | 280.0 (97) | 210.9 ± 34.0 (104) |

Human lung MC (three donors) were isolated as described in the text and kept in culture (RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% FCS) for 24 hours before release experiments were performed. MC were first incubated with IgE (10 μg/mL, 3 hours). Cells were then washed and exposed to control medium or anti-IgE MoAb E-124-2-8 (concentrations as indicated) at 37°C for 45 minutes. Thereafter, cells were centrifuged and the cell-free supernatants recovered and analyzed for the presence of MCP-1 by ELISA. The results show the MCP-1 concentrations (pg per mL) in the supernatants (mean of duplicates) in the three donors, and the mean ± SD of all data in the three donors.

A significant increase in MCP-1 in the supernatants as compared with control (P < .05) was obtained using 10 μg anti-IgE per mL.

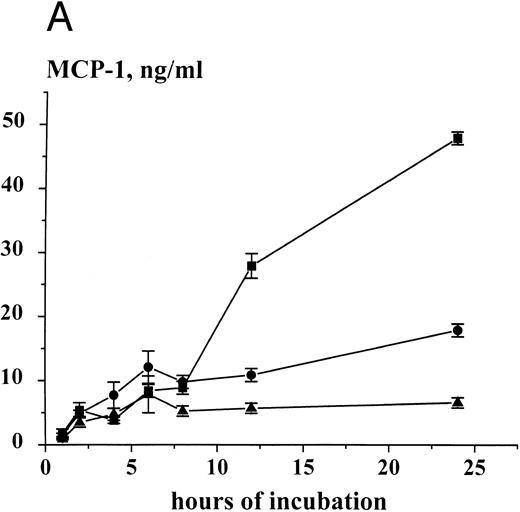

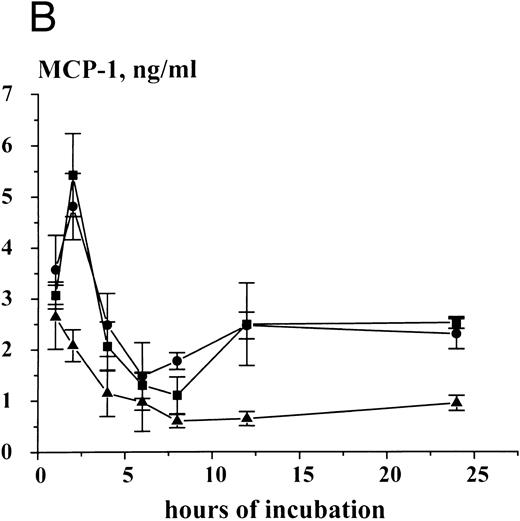

Time-dependent expression and release of MCP-1 in HMC-1 cells. HMC-1 cells (1 × 106 per mL) were cultured for various time periods in the presence of control medium (▴), rhSCF (100 ng/mL) (•), or a mixture of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) and PMA (50 ng/mL) (▪). After culture, cells were harvested, and MCP-1 peptide measured in supernatants (A) and cell lysates (B) by an ELISA. An accumulation of MCP-1 in the supernatants of either untreated or SCF-treated HMC-1 cells was seen. However, stimulation of cells with rhSCF or rhSCF + PMA significantly increased MCP-1 peptide release above control over time (A). The SCF-induced increase in MCP-1 expression in cell lysates (B) indicates induction of peptide synthesis. The results represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate cultures from one typical experiment. Similar data were obtained in two other experiments.

Time-dependent expression and release of MCP-1 in HMC-1 cells. HMC-1 cells (1 × 106 per mL) were cultured for various time periods in the presence of control medium (▴), rhSCF (100 ng/mL) (•), or a mixture of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) and PMA (50 ng/mL) (▪). After culture, cells were harvested, and MCP-1 peptide measured in supernatants (A) and cell lysates (B) by an ELISA. An accumulation of MCP-1 in the supernatants of either untreated or SCF-treated HMC-1 cells was seen. However, stimulation of cells with rhSCF or rhSCF + PMA significantly increased MCP-1 peptide release above control over time (A). The SCF-induced increase in MCP-1 expression in cell lysates (B) indicates induction of peptide synthesis. The results represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate cultures from one typical experiment. Similar data were obtained in two other experiments.

RESULTS

Expression of MCP-1 mRNA in human MC. Northern blot analyses were performed using highly purified unstimulated lung MC (pool of MC from six donors; in each preparation, MC were >98% pure), with 91% pure elutriated lung MC exposed to control medium or rhSCF (100 ng per mL) for 2 hours, as well as with HMC-1 cells cultured in the presence or absence of rhSCF (or a mixture of SCF, [100 ng/mL] and PMA, [50 ng/mL]) for up to 24 hours. All Northern blot experiments were performed using oligonucleotide probes.

Baseline amounts of MCP-1 mRNA were detectable in unstimulated pure MC, although these baseline levels were low (91% pure MC, Fig 1) or nearly undetectable (>98% pure MC). However, exposure of MC to rhSCF was followed by a substantial increase in expression of MCP-1 mRNA (Fig 1). Corresponding data were obtained for greater than 98% pure MC using RT-PCR (Fig 2). Again, baseline levels of MCP-1 mRNA were detectable in ultrapure MC, and incubation of cells in rhSCF was followed by a significant increase in detectable MCP-1 mRNA (Fig 2A). Incubation of MC with anti-IgE (10 μg/mL) or a combination of anti-IgE (10 μg/mL) and SCF (100 ng/mL) for 2 or 8 hours was also followed by an increase in detectable MCP-1 mRNA in RT-PCR analysis (Fig 2B).

The HMC-1 cell line, which contains an activating point mutation in the catalytic domain of c-kit (SCF-receptor), was found to express substantial amounts of MCP-1 mRNA in a constitutive manner (Figs 2 and 3). Exposure of HMC-1 cells to rhSCF (100 ng/mL) or a mixture of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) and PMA (50 ng/mL) for 0.5 to 24 hours (Fig 3), led to a substantial increase in MCP-1 mRNA expression when compared with untreated cells.

Expression of other chemokines in MC was also analyzed by Northern blotting. In these experiments, expression of mRNA specific for MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, or IL-8 was not detectable in untreated (91% or >98% pure) or SCF-treated (91% pure) lung MC (Fig 1). In untreated HMC-1, expression of chemokines other than MCP-1 could also not be detected. However, after exposure to rhSCF (100 ng/mL) and PMA (50 ng/mL) for 0.5 to 24 hours, HMC-1 cells were found to express MIP-1β mRNA and very low amounts of MIP-1α mRNA (Fig 3). All Northern blot experiments were appropriately controlled: Thus, the purified lung MC were found to express SCF receptor (c-kit)- and β-actin mRNA (Fig 1), but not SCF-, c-fms-, or CD25 mRNA. The oligonucleotide probes specific for IL-8 and RANTES, which did not give a positive blot signal with MC, showed positive results in Northern blots performed with activated lung fibroblasts (not shown).

Detection of MCP-1 in human MC by ELISA. Immunologically detectable MCP-1 was measured by an ELISA in supernatants and lysates of primary lung MC and HMC-1 cells. In primary untreated lung MC (91% or >98% pure), measurable amounts of MCP-1 were detectable. In 2-hour supernatants of 91% pure unstimulated MC (one donor), the level of measurable MCP-1 was 1,923 pg/106/mL, whereas in SCF-treated, 91% pure MC (100 ng/mL, 2 hours; same donor), the MCP-1 level amounted to 2,382 pg/106/mL. In greater than 98% pure untreated lung MC, the MCP-1 level in the supernatant was 159 ± 27 pg/106/mL after 1 hour, and 576 ± 47 pg/106/mL after 2 hours. Exposure of (>98%) pure MC to rhSCF for 2 hours at 37°C resulted in a significant increase in detectable MCP-1 in cell supernatants (control, 576 ± 47 v rhSCF, 1,224 ± 271). Stimulation of MC with anti-IgE MoAb E-124-2-8 for 45 minutes (after preincubation with IgE) also resulted in detectable MCP-1 release (control, 202 ± 21 v anti-IgE, 10 μg/mL, 553.3 ± 210.6 pg/106/mL of MCP-1; P < .05) (Table 2). The calculated amount of MCP-1 per 106 lung MC (lysates of washed cells) amounted to 326 ± 63 pg, whereas 106 HMC-1 cells were found to contain 2,081 ± 313 pg MCP-1. Similar to primary MC, HMC-1 cells were found to release MCP-1 into supernatants in a constitutive manner, and the MCP-1 peptide accumulated in HMC-1 supernatants over time reaching a plateau level at 8 hours (Fig 4A). Exposure of HMC-1 cells to rhSCF or a mixture of rhSCF (100 ng/mL) and PMA (50 ng/mL) resulted in an increased release of MCP-1 into supernatants over time when compared with untreated cells (Fig 4A). The cellular MCP-1 levels also increased in HMC-1 cells in response to rhSCF or rhSCF plus PMA, with two peptide-peaks, one observed at 2 hours and one observed at 12 hours, respectively (Fig 4B). Moreover, the effect of SCF on MCP-1 expression and release was found to be dose-dependent, with a maximum stimulation observed with 50 or 100 ng/mL of recombinant SCF (Table 3).

Dose-Dependent Expression and Release of MCP-1 in HMC-1 Cells in Response to SCF

| Stimulus . | MCP-1 Concentration, % of Control . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Sup 8 h . | Lysates 8 h . | Sup 12 h . | Lysates 12 h . |

| none | 100 ± 8 | 100 ± 23 | 100 ± 4 | 100 ± 25 |

| SCF, 1 ng/mL | 200 ± 18 | 258 ± 85 | 282 ± 22 | 235 ± 14 |

| SCF, 5 ng/mL | 215 ± 13 | 294 ± 35 | 295 ± 14 | 361 ± 20 |

| SCF, 10 ng/mL | 228 ± 12 | 483 ± 39 | 305 ± 27 | 324 ± 31 |

| SCF, 50 ng/mL | 458 ± 22 | 643 ± 52 | 480 ± 8 | 620 ± 63 |

| SCF, 100 ng/mL | 409 ± 37 | 611 ± 20 | 443 ± 13 | 475 ± 24 |

| SCF, 200 ng/mL | 466 ± 22 | 506 ± 38 | 442 ± 41 | 353 ± 21 |

| Stimulus . | MCP-1 Concentration, % of Control . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Sup 8 h . | Lysates 8 h . | Sup 12 h . | Lysates 12 h . |

| none | 100 ± 8 | 100 ± 23 | 100 ± 4 | 100 ± 25 |

| SCF, 1 ng/mL | 200 ± 18 | 258 ± 85 | 282 ± 22 | 235 ± 14 |

| SCF, 5 ng/mL | 215 ± 13 | 294 ± 35 | 295 ± 14 | 361 ± 20 |

| SCF, 10 ng/mL | 228 ± 12 | 483 ± 39 | 305 ± 27 | 324 ± 31 |

| SCF, 50 ng/mL | 458 ± 22 | 643 ± 52 | 480 ± 8 | 620 ± 63 |

| SCF, 100 ng/mL | 409 ± 37 | 611 ± 20 | 443 ± 13 | 475 ± 24 |

| SCF, 200 ng/mL | 466 ± 22 | 506 ± 38 | 442 ± 41 | 353 ± 21 |

HMC-1 cells were exposed to various concentrations of rhSCF (as indicated) and PMA (50 ng/mL) for 8 h or 12 h at 37°C in complete medium. After incubation, cells were centrifuged and the supernatants (sup) recovered. MCP-1 was measured in lysates and sups by ELISA. As visible, SCF induced an increase in cellular MCP-1 and MCP-1 release in a dose-dependent manner. The results represent the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures from one experiment. A similar dose-dependency was obtained with SCF in the absence of PMA (not shown).

Abbreviations: sup, supernatants; h, hour.

We next asked if MC also express and release detectable amounts of chemokines other than MCP-1. In these experiments, unstimulated HMC-1 cells were found to express low, but detectable amounts, of MIP-1β (171 ± 27.5 pg per 106 cells). Exposure of HMC-1 cells to rhSCF resulted in an increased expression of MIP-1β peptide (rhSCF, 2 hours, 608 ± 36 pg per 106 cells, P < .05). In unstimulated HMC-1 cells, the levels of MIP-1α were at or below the detectable limit. However, exposure of HMC-1 to rhSCF for 2 hours resulted in a slight increase in immunologically detectable MIP-1α in lysates (control, 18 ± 10 v rhSCF, 119 ± 12 pg per 106 cells, P < .05) and supernatants (control, 33 ± 3 v rhSCF, 2 hours, 52 ± 2 pg per 106 cells per mL, P < .05). IL-8 and RANTES were not detectable in lysates or supernatants of untreated or rhSCF-treated HMC-1 cells, whereas monocyte-supernatants contained huge amounts of both IL-8 and RANTES (=positive control, not shown).

In a next series of experiments, various types of cells including MC, were analyzed and compared for expression of MCP-1 peptide. In these experiments, purified lung MC and blood monocytes were found to produce similar amounts of MCP-1. HMC-1 cells were found to produce relatively large quantities of MCP-1 when compared with primary MC or to the other myeloid cell lines tested, ie, HL-60, KG-1, and U937 (Table 4). As expected, HUVEC produced huge amounts of MCP-1, even exceeding the peptide amount measurable in HMC-1 cells. Also, the lung cell fractions containing less than 1% MC were found to express substantial amounts of MCP-1. A summary of the ELISA results obtained with different types of cells is shown in Table 4.

Measurement of MCP-1 in Various Human Cells by ELISA

| Cell Type . | MCP-1 (pg/mL) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | 2-Hour Supernatant4-150 . | Cell Lysate4-151 . |

| Lung MC (98% pure) | 576 ± 47 | 326 ± 63 |

| Lung cells without MC (<1%) | 1,227 ± 570 | 170 ± 70 |

| HMC-1 (mast cell line) | 3,483 ± 735 | 2,081 ± 313 |

| PB MNC | 166 ± 120 | 187 ± 35 |

| Blood monocytes (Mo) | 163 ± 20 | 384 ± 128 |

| Eosinophils (HES) | <5 | <5 |

| BM MNC | <5 | <5 |

| HUVEC | >5,000 | NT |

| HL-60 (myeloid cell line) | NT | 350 ± 70 |

| KG-1 (myeloid cell line) | 66 ± 9 | 22 ± 12 |

| U937 (monoblastoid cell line) | <5 | 24 ± 5 |

| Cell Type . | MCP-1 (pg/mL) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | 2-Hour Supernatant4-150 . | Cell Lysate4-151 . |

| Lung MC (98% pure) | 576 ± 47 | 326 ± 63 |

| Lung cells without MC (<1%) | 1,227 ± 570 | 170 ± 70 |

| HMC-1 (mast cell line) | 3,483 ± 735 | 2,081 ± 313 |

| PB MNC | 166 ± 120 | 187 ± 35 |

| Blood monocytes (Mo) | 163 ± 20 | 384 ± 128 |

| Eosinophils (HES) | <5 | <5 |

| BM MNC | <5 | <5 |

| HUVEC | >5,000 | NT |

| HL-60 (myeloid cell line) | NT | 350 ± 70 |

| KG-1 (myeloid cell line) | 66 ± 9 | 22 ± 12 |

| U937 (monoblastoid cell line) | <5 | 24 ± 5 |

Abbreviations: NT, not tested; PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow; HUVEC, cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. MCP-1 was measured by a commercial ELISA.

Supernatants were obtained from cell cultures containing 1 × 106 cells per mL, after a 2-hour incubation period.

Cell lysates were prepared from 105 to 107 cells and results expressed as pg per 106 cells. All results represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments (cell lines) or donors (primary cells).

Detection of MCP-1 in MC by in situ staining. In a number of experiments, purified lung MC and HMC-1 cells were examined for expression of MCP-1 peptide by an in situ staining technique. In these experiments, purified lung MC exposed to rhSCF or control medium (2 to 12 hours), as well as HMC-1 cells (untreated), were spun onto cytospin slides. Immunohistochemistry was performed using anti–MCP-1 antibody S101 (Fig 5). After exposure to rhSCF, a subset of primary lung MC (approximately 10% to 20% of cells) were found to react with MoAb S101 (Fig 5B), whereas untreated lung MC did not at all react with S101 (Fig 5A). By contrast HMC-1 cells were found to be labeled by MoAb S101 even as untreated cells (Fig 5C). A granular staining pattern was obtained in both types of cells (lung MC and HMC-1). The antitryptase MoAb G3 (positive control) produced strong cytoplasmic staining (granular pattern) in the vast majority (>95%) of isolated lung MC. More than 99% of HMC-1 cells were found to react with MoAb G3 (not shown).

Immunohistochemistry of MC with an antibody against MCP-1. Purified human lung MC (A and B) and HMC-1 cells (C) were spun onto cytospin slides and stained with an antibody against MCP-1 (S101) as described in Materials and Methods. Primary lung MC were exposed to control medium (A) or rhSCF (B) for 2 hours before being exposed to S101. HMC-1 were used as untreated cells. Reactivity of lung MC with S101 was visualized by streptavidin-peroxidase and AEC and reactivity of HMC-1 cells with the antibody by alkaline phosphatase and neofuchsin (C). Note that expression of MCP-1 in lung MC was demonstrable after exposure to rhSCF, but not in control medium. Similar staining results were obtained when cells were exposed for 2 hours or 12 hours.

Immunohistochemistry of MC with an antibody against MCP-1. Purified human lung MC (A and B) and HMC-1 cells (C) were spun onto cytospin slides and stained with an antibody against MCP-1 (S101) as described in Materials and Methods. Primary lung MC were exposed to control medium (A) or rhSCF (B) for 2 hours before being exposed to S101. HMC-1 were used as untreated cells. Reactivity of lung MC with S101 was visualized by streptavidin-peroxidase and AEC and reactivity of HMC-1 cells with the antibody by alkaline phosphatase and neofuchsin (C). Note that expression of MCP-1 in lung MC was demonstrable after exposure to rhSCF, but not in control medium. Similar staining results were obtained when cells were exposed for 2 hours or 12 hours.

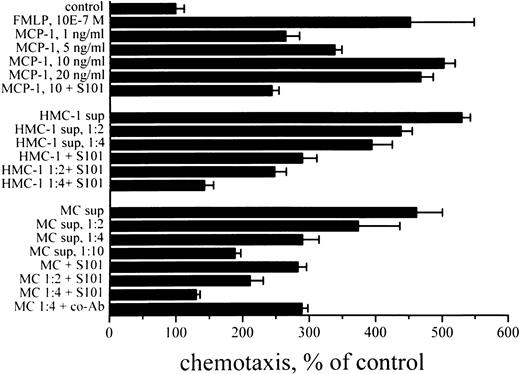

Demonstration of a chemotactic effect of MCP-1 derived from human MC. The chemotactic effect of MC-derived MCP-1 was analyzed in a chemotaxis chamber assay using enriched blood monocytes (Mo, >80% pure) and MC supernatants. In this chemotaxis assay, recombinant MCP-1 induced migration of blood monocytes in a dose-dependent manner with a plateau level at 10 ng/mL of rhMCP-1 (Fig 6). Supernatants of lung MC or HMC-1 also induced significant and dose-dependent migratory responses in Mo, comparable to the effects of rhMCP-1. The migration-inducing effects of MC-supernatants, HMC-1 supernatants, and rhMCP-1 could all be inhibited significantly by neutralizing anti–MCP-1 antibody S101 (P < .05) (Fig 6) and anti–MCP-1 antibody S14 (P < .05, data not shown), but not by a control antibody (anti–IL-8 MoAb DM/C7; P > .05) (Fig 6). Checkerboard analysis confirmed that the migration-inducing effects of both rhMCP-1 and mast cell supernatants were due to chemotaxis, not merely chemokinesis (Table 5).

Mast cell supernatant-induced chemotaxis of human Mo. Mo were purified by Percoll gradient centrifugation. Purified Mo were placed in the upper chambers of the chemotaxis assay. Various concentrations of rhMCP-1 (as indicated), various dilutions of HMC-1 sup, various dilutions of lung MC sup (91% pure lung MC, 2-hour incubation, 1,923 pg/mL of MCP-1 by ELISA), FMLP (10−7 mol/L = 10E-7 mol/L) (as positive control) or control medium were added into the lower chambers. MCP-1 and sup of MC or HMC-1 were applied in the presence or absence of blocking anti–MCP-1 antibody S101 (10 μg/mL). After 3 hours of incubation, the nonmigrated Mo were removed together with the filter, and the migrated Mo were recovered from the lower chambers and counted by use of the fluorescence dye calcein AM (5 mmol/L). The X-axis shows the percentage of migrated Mo as compared with the control (=number of Mo migrated against control medium into the lower chambers = 100%). Results represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Mast cell supernatant-induced chemotaxis of human Mo. Mo were purified by Percoll gradient centrifugation. Purified Mo were placed in the upper chambers of the chemotaxis assay. Various concentrations of rhMCP-1 (as indicated), various dilutions of HMC-1 sup, various dilutions of lung MC sup (91% pure lung MC, 2-hour incubation, 1,923 pg/mL of MCP-1 by ELISA), FMLP (10−7 mol/L = 10E-7 mol/L) (as positive control) or control medium were added into the lower chambers. MCP-1 and sup of MC or HMC-1 were applied in the presence or absence of blocking anti–MCP-1 antibody S101 (10 μg/mL). After 3 hours of incubation, the nonmigrated Mo were removed together with the filter, and the migrated Mo were recovered from the lower chambers and counted by use of the fluorescence dye calcein AM (5 mmol/L). The X-axis shows the percentage of migrated Mo as compared with the control (=number of Mo migrated against control medium into the lower chambers = 100%). Results represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Checkerboard Analysis of MCP-1 and HMC-1 sup-Induced Migration of Blood Mo

| Lower Chamber . | Upper Chamber, MCP-1, ng/mL . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCP-1, ng/mL . | 0 . | 1 . | 5 . | 10 . |

| 0 | 3,217 | 2,841 | 2,567 | 2,234 |

| 1 | 9,828 | 7,968 | 6,211 | 4,209 |

| 5 | 12,606 | 9,752 | 7,687 | 5,097 |

| 10 | 17,388 | 14,590 | 9,683 | 6,679 |

| Lower Chamber | Upper Chamber, % HMC-1 sup | |||

| % HMC-1 sup | 0 | 25 | 50 | 100 |

| 0 | 3,560 | 3,140 | 2,653 | 2,154 |

| 25 | 13,612 | 11,456 | 9,743 | 6,051 |

| 50 | 14,508 | 11,946 | 10,216 | 6,348 |

| 100 | 16,840 | 12,015 | 10,519 | 7,506 |

| Lower Chamber . | Upper Chamber, MCP-1, ng/mL . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCP-1, ng/mL . | 0 . | 1 . | 5 . | 10 . |

| 0 | 3,217 | 2,841 | 2,567 | 2,234 |

| 1 | 9,828 | 7,968 | 6,211 | 4,209 |

| 5 | 12,606 | 9,752 | 7,687 | 5,097 |

| 10 | 17,388 | 14,590 | 9,683 | 6,679 |

| Lower Chamber | Upper Chamber, % HMC-1 sup | |||

| % HMC-1 sup | 0 | 25 | 50 | 100 |

| 0 | 3,560 | 3,140 | 2,653 | 2,154 |

| 25 | 13,612 | 11,456 | 9,743 | 6,051 |

| 50 | 14,508 | 11,946 | 10,216 | 6,348 |

| 100 | 16,840 | 12,015 | 10,519 | 7,506 |

Checkerboard analysis of MCP-1–induced and HMC-1 sup-induced migration of blood Mo was done as described in the text. Cells were loaded in the upper chamber and after induction by rhMCP-1 or HMC-1 sup and the numbers of migrated Mo were counted in the lower chambers by dye (calcein AM) staining. Various concentrations of rhMCP-1 or HMC-1 sup were applied in either the lower or upper chambers of the chemotaxis assay system, or into both (upper and lower chambers). Selective migration of Mo against MCP-1 and HMC-1-sup suggests a chemotactic response.

DISCUSSION

Because MC have been implicated in the regulation of leukocyte chemotaxis and inflammation,33-35 38 we have analyzed expression of chemotactic peptides in primary human lung MC and the human mast cell line, HMC-1. Our experiments show that primary lung MC and HMC-1 cells produce and release biologically active MCP-1. The level of expression of MCP-1 mRNA in resting MC was found to be rather low. However, exposure to SCF, a major regulator of MC, was followed by a significant increase in expression and release of MCP-1 in human MC. Expression of MCP-1 in primary MC was demonstrable by Northern blot and RT-PCR analysis, as well as by ELISA and in situ staining experiments. Because more than 90% (and for PCR analysis even >98%) of examined cells were MC and because the MC agonist SCF showed an effect on mRNA expression, the possibility that the peptide was expressed in contaminating cells, but not MC, seems rather unlikely. Our in situ staining experiments are also in favor of the notion that primary lung MC can express MCP-1.

The observation that unstimulated (isolated) lung MC express low, albeit detectable amounts of MCP-1, is of interest, as this peptide primarily is produced on demand, for example in inflammatory reactions.11,12,14,15,51 52 The question as to whether normal resting MC in vivo express baseline levels of MCP-1 mRNA remains, at present, unknown. For example, it may well be that the isolation procedure or exposure to plastic surface caused expression of (low levels of ) MCP-1 mRNA in primary MC. So far, various attempts to identify MCP-1 in human lung MC by in situ staining of tissues gave negative results (not shown). However, even the isolated, untreated lung MC, which expressed low amounts of MCP-1 by RT-PCR, did not stain with antibodies against MCP-1. In situ hybridization experiments are in progress to clarify if tissue MC express significant amounts of MCP-1 mRNA as resting cells or in inflammatory diseases.

SCF is a well known regulator of human MC.53,54 Thus, SCF promotes the differentiation and survival of MC, as well as mediator release and MC chemotaxis.55-60 In the present study, SCF was found to promote expression of MCP-1 mRNA and release of MCP-1 peptide in isolated MC, as well as in HMC-1 cells. To our knowledge, this is the first report that SCF induces expression and release of a chemotactic peptide in human MC. The observation is in line with the general notion that SCF is a major regulator of MC. Thus, based on our data, it is tempting to speculate that SCF plays a role in MC-dependent reactions associated with accumulation of MCP-1–responsive leukocytes in the tissues. However, SCF may not be the only factor that regulates MCP-1 expression. The observation that anti-IgE stimulation also augments MCP-1 expression and release in human MC is of interest and is in line with the notion that IgE-dependent activation of murine MC induces expression of multiple cytokines and chemokines.38

The HMC-1 cell line contains two point mutations in the catalytic (kinase) domain of c-kit (SCF-receptor), a defect that is associated with autonomous (SCF-independent) cell signaling.61 Interestingly, in contrast to primary MC, HMC-1 cells were found to express huge amounts of MCP-1 mRNA and MCP-1 peptide in a constitutive manner. It is tempting to speculate that the mutation and intrinsic activation of SCF receptor is associated with high level transcription of the MCP-1 gene product. A remarkable observation was that SCF was able to further promote expression of MCP-1 mRNA expression in HMC-1 cells. This observation may indicate that the SCF receptor is not maximally stimulated by the mutation. The possibility that the HMC-1 cell subclone used in our laboratory had lost the mutation (during long-term culture and passage) could be excluded by PCR analysis and sequencing of c-kit (both mutations, ie, Val → Gly [560] and Asp → Val [816]61 were present).

The time kinetics of MCP-1 release in HMC-1 cells after exposure to rhSCF or rhSCF + PMA showed a biphasic increase with a first peak of MCP-1 release observed after 6 hours, and a second phase of peptide increase occurring after 12 hours. Interestingly, the first peak was more pronounced in cell cultures containing SCF, but not PMA (compared with SCF + PMA), whereas the second phase of peptide increase was more pronounced in SCF + PMA cultures (compared with SCF alone). The reason for the different kinetics and the MCP-1 peak profiles are not known. One possibility could be that the first increase is due to release of newly transcribed and/or preformed peptide, whereas the second increase is primarily due to release of de novo-synthesized peptide. Remarkably, a similar biphasic increase in response to SCF can be seen with TNF-α release in HMC-1 cells (unpublished results, 1992). Another interesting phenomenon was that SCF + PMA produced an increased level of released, but not cellular MCP-1, when compared with SCF alone. This phenomenon can, at present, not readily be explained. One possibility could be that the turnover of MCP-1 peptide production and release in SCF + PMA-treated cells was higher, as compared with SCF-treated cells.

MCP-1 is a major regulator of monocyte chemotaxis.1 Correspondingly, rhMCP-1, as well as MC supernatants containing immunologically detectable MCP-1, induced Mo chemotaxis, and this effect could be blocked by a neutralizing anti–MCP-1 antibody. However, MCP-1 exerts multiple biologic activities and acts not only on monocytes, but also on eosinophils, T lymphocytes, and basophils.1,6-8 For example, MCP-1 is a potent activation factor for human blood basophils and can induce histamine release in these cells.6,7 62-64 Thus, MCP-1 might be involved in the cross-talk between MC and basophils and various other types of immune cells.

The expression of MCP-1 in SCF-activated human MC may have several biologic implications. Thus, MC accumulate in various inflammatory processes and supposedly are involved in the regulation of leukocyte transmigration through endothelial cells.33-35 Also, MC activation is often associated with accumulation of other leukocytes in inflammed areas.26 From our data, we believe that MCP-1 plays a major role in the regulation of chemotaxis and accumulation of leukocytes during MC-dependent tissue reactions. This hypothesis is also supported by the recent observation that MC-dependent allergic disorders are associated with elevated MCP-1 production.20-24 For example, Kuna et al23 showed that MCP-1 levels (but not other chemokines) increase in nasal secretions obtained from patients with allergic rhinitis during the allergy season, when compared with preseasonal values.

A number of recent studies suggest that MC are a source of multiple cytokines and peptide mediators.35-39 In the human system, however, only few data on chemokine production in MC have been reported so far. Recent data have shown that HMC-1 cells express multiple chemokines.65 In one study, human skin MC have been described as expressing IL-8.39 In the present study, however, we were not able to detect IL-8 expression in MC. These differences may be due to the different types of MC analyzed (lung MC v skin MC). Another possibility could be that MC express extremely low amounts of IL-8, which could not be detected by the techniques applied (ie, Northern blotting and ELISA). It also remains unknown whether MC express significant amounts of MCP-2, -3 or -4.

In summary, our data show that human lung MC, as well as HMC-1 cells, express MCP-1 mRNA and MCP-1 peptide. Moreover, this study shows that SCF promotes expression and release of MCP-1 in human MC. MCP-1 may play a role in the accumulation of (responsive) leukocytes in mast cell-dependent processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Hans Semper for skillful technical assistance.

Supported by Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschafteichen Forschung in Österreich (Vienna, Austria) Grant No. P-9359, F-005/01, and S6707.

Address reprint requests to Peter Valent, MD, Department of Internal Medicine I, Division of Hematology, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, A-1090 Vienna, Austria.

![Fig. 2. RT-PCR analysis of human MC. RT-PCR analyses were performed on highly purified lung MC (purity, <98%) ([A], lanes 1 through 8; [B], all lanes) and the mast cell line HMC-1 ([A], lanes 9 and 10) using primers specific for MCP-1 and β-actin. (A) Shows the effect of SCF on MCP-1 mRNA expression: primary MC were exposed to rhSCF or control medium for 2 or 8 hours. mRNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis was done as described in the text. Exposure of lung MC to rhSCF led to an increase in expression of MCP-1 mRNA after 2 hours (lane 4) and 8 hours (lane 8), compared with control (2 hours, lane 2; and after 8 hours, lane 6). RT-PCR analysis of lung MC was controlled by using primers specific for β-actin (lane 1, control medium, 2 hours; lane 3, rhSCF, 2 hours; lane 5, control medium, 8 hours; lane 7, rhSCF, 8 hours). HMC-1 cells expressed significant amounts of MCP-1 mRNA (lane 10) in a constitutive manner. Lane 9, β-actin control of HMC-1 cells. (B) Shows the effect of anti-IgE and anti-IgE + SCF on MC. Highly purified lung MC (<98%) were exposed to control medium (lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8), anti-IgE MoAb E-124-2-8, 10 μg/mL (lanes 3, 4, 9, and 10), and rhSCF, 100 ng/mL plus anti-IgE, 10 μg/mL (lanes 5, 6, 11, and 12) for 2 hours (lanes 1 through 6) or 8 hours (lanes 7 through 12) at 37°C. RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for MCP-1 (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12) and β-actin (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11). As visible, anti-IgE and anti-IgE + SCF augmented MCP-1 mRNA expression in lung MC.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/90/11/10.1182_blood.v90.11.4438/3/m_bl_0032f2a.jpeg?Expires=1765933070&Signature=piTwA~oeaTaOeLpnyhqVq9KHBJBnJiFAuj4hD4s70pN8tY4EUaqQp7Y9V5Xd3gtczamfhn1SOCKIaGiZ2iZl26BHnT7zQZaclnz3f2GaOQHW9sh2HnUnb2A~-5t87DNslt2SUGVlDyeYKmc3OqZ1HQbLUeD5-Oa6Ms1OJqSkF~6pRSqFNS5NKsGVSxXYwxNi9dCaos~DlVlN1Lb-tpMyMdPuc9kC4x44NqONYsdWa7ESFjYG-2hJki90PGrwEQc-9d6LKM-53H4H4jgUrVghBeSIUkTaqRRqCMdt2BIAIh0doQXbyJqyQi3cU0pgb5ZK950laaSCkxpUXYV4BSNbmg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 2. RT-PCR analysis of human MC. RT-PCR analyses were performed on highly purified lung MC (purity, <98%) ([A], lanes 1 through 8; [B], all lanes) and the mast cell line HMC-1 ([A], lanes 9 and 10) using primers specific for MCP-1 and β-actin. (A) Shows the effect of SCF on MCP-1 mRNA expression: primary MC were exposed to rhSCF or control medium for 2 or 8 hours. mRNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis was done as described in the text. Exposure of lung MC to rhSCF led to an increase in expression of MCP-1 mRNA after 2 hours (lane 4) and 8 hours (lane 8), compared with control (2 hours, lane 2; and after 8 hours, lane 6). RT-PCR analysis of lung MC was controlled by using primers specific for β-actin (lane 1, control medium, 2 hours; lane 3, rhSCF, 2 hours; lane 5, control medium, 8 hours; lane 7, rhSCF, 8 hours). HMC-1 cells expressed significant amounts of MCP-1 mRNA (lane 10) in a constitutive manner. Lane 9, β-actin control of HMC-1 cells. (B) Shows the effect of anti-IgE and anti-IgE + SCF on MC. Highly purified lung MC (<98%) were exposed to control medium (lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8), anti-IgE MoAb E-124-2-8, 10 μg/mL (lanes 3, 4, 9, and 10), and rhSCF, 100 ng/mL plus anti-IgE, 10 μg/mL (lanes 5, 6, 11, and 12) for 2 hours (lanes 1 through 6) or 8 hours (lanes 7 through 12) at 37°C. RT-PCR was performed using primers specific for MCP-1 (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12) and β-actin (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11). As visible, anti-IgE and anti-IgE + SCF augmented MCP-1 mRNA expression in lung MC.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/90/11/10.1182_blood.v90.11.4438/3/m_bl_0032f2b.jpeg?Expires=1765933070&Signature=MOyMOgLkXxx0oWAoCeDHCJoMmZ9UWfex9uT9dKkK-uguk4oyudVcOMWrB5i23lNL7jTy7oqw5Yb0wOWvYKnue9dxIYmrKRrkbDeQZ-7ShoHUR-6amSLRYXaVHF8eG1IaYDppgOEXm4xIgRKHMoTuKSMVDFAFfchFDbaOsRHvXSei8y8nqUagU6RxnFdioe70~CgRznGtvBt-P8buKA2HMAUmSmSI2cGZC64zHUjWuDar27r6-iJJmXEnxhI24wX1DKbK9XBLKvFJn9V5WpHtSkVN8WRxTheBDMztOzigMoiPRZ0KG3X5kcGGCjIVXUZbJx5boW1pA5tZnBmKm5bFbQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal