THE PLASMA CONCENTRATION of IgG has a direct bearing on the health of the host. Of all Ig deficiencies, only agammaglobulinemia is associated with certain fatal outcome in the absence of supplementation therapy. Since the time of Ehrlich1 in the 1890s, the transmission of immunity from mother to young was known to be essential to the health of the newborn, protecting the newborn from infection during the first weeks of life until its own immune responses could assume this function.

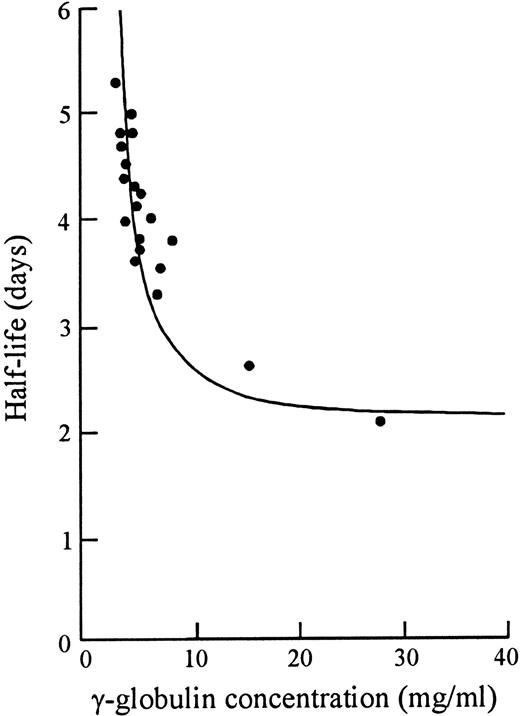

Forty years ago in 1958, Prof F.W.R. Brambell described a saturable receptor system (in fact, the first IgG receptor) that mediates this transport of Ig from mother to young, via yolk sac, intestine, or placenta.2 Analogous systems have since been shown or suggested in mammals (excepting, perhaps, ruminants), birds, reptiles, and fish.3 Subsequently, in 1964, Brambell inferred the presence of a similar or identical receptor system that protected IgG from catabolism to make it the longest surviving of all plasma proteins.4 IgG was unique in that it had increased fractional catabolism at higher plasma concentrations (Fig 1).5 This was paradoxical in that any receptor for catabolism should show less catabolism as it becomes saturated with IgG. To Brambell this suggested instead a nonsaturable catabolism mechanism and a saturable protection mechanism specific for IgG. After bulk phase endocytosis of IgG with other plasma proteins, he proposed that IgG was selectively returned to circulation via a protection receptor that rescued it from the pathway to lysosomes and catabolism that was the fate of other plasma proteins.4 6

Relation of half-life to serum concentration of γ-globulin in mice. Data derived from Sell and Fahey,5 with simulation according to the receptor model of Brambell et al.4 Adapted and reprinted with permission from Brambell et al.4

In the mid 1950s to early 1960s, pharmacokinetic studies indicated that most plasma proteins, including IgG, were catabolized in close contact with the vascular space and, furthermore, that no single organ was responsible for more than 10% of the total catabolism.7,8 This led Waldmann and Strober8 in 1969 to infer that the catabolic site for IgG and other proteins was most likely the vascular endothelium. Nearly 30 years later, this was supported by work demonstrating the protection receptor in endothelial cell lines9,10 and in endothelium in tissue sections.10

By a somewhat circuitous route (see Junghans3 for historical overview), the Brambell receptor (FcRB) was eventually shown both to mediate the transmission of IgG in the antenatal and/or neonatal period, in this expression termed FcRn,11 and to mediate the protection of IgG from catabolism, in this expression termed FcRp.12 Cloning showed a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-related heavy chain and a β2-microglobulin light chain.11 Mice knocked out for light chain (β2m−/−) lost transport of IgG from mother to young13 and similarly showed accelerated catabolism of IgG9,12,14 that equaled that of albumin in the same mice, which is not protected.12 Other studies of β2m−/− mice showed abolition of MHC class I-related functions, such as CD8 T-cell interactions, but normal T-helper functions, including B-cell help, were unaffected, with normal IgA and IgM levels; the B-cell compartment was the same size12 15-17 (D. Roopenian, personal communication).

The concentration of IgG at steady state (Css ), like all plasma proteins, is a balance between synthesis and catabolism:

in which q is the biosynthetic rate (in micrograms per milliliter per day) and k10 is the fractional catabolic rate constant (day−1). The FcRp functions to decrease the catabolic rate of IgG, thereby generating higher IgG levels (Eq. 1). In mice knocked-out for FcRB light chain, there was a near 10-fold decrease in IgG levels that is attributable to the action of the receptor.9,12,13,16 In humans, important susceptibilities are noted in hypogammaglobulinemic individuals with plasma IgG of 1/10th normal levels.18 A 10-fold improvement in IgG levels induced by the FcRp is therefore clinically important. From another perspective, the FcRp reduces the number of plasma cells that the body would otherwise need to maintain adequate IgG levels to guard against infection.

By this model, as IgG synthesis and serum IgG increased, the protection mechanism would progressively saturate and the catabolic rate would increase (Fig 1). The bend of the hyperbolic curve (Fig 1) is in the range of normal IgG levels in normal pathogen environments.8 This was predicted to yield a fairly narrow concentration range for normal IgG levels despite a wider range of IgG synthesis rates.19 However, it is probable that the sole selective pressure for creation of the FcRp was to raise total IgG to a useful protective range, rather than to prevent “excessively” high levels of IgG. When one looks at the physiological effects of complete IgG myeloma proteins, there is little evidence that intact IgG (without free heavy or light chains) has any deleterious effect at any concentration that could mediate a selective pressure to control against high levels.

Although numerous studies have shown that plasma IgG levels influence catabolism rates, which in turn regulate IgG levels,8 there has been an enduring impression that IgG levels also regulate IgG production. This “immunoregulatory feedback” was stated most cogently by Bystryn et al20 in 1971: “[It is suggested] that under physiologic conditions the level of serum antibody can regulate antibody synthesis. Hence, it can be postulated that a feedback mechanism exists ... [by] ‘sensing’ of specific antibody levels ...” Such a feedback would imply an undefined receptor on plasma cells and/or B cells, perhaps involving unmetabolized antigen complexes,20 to sense the IgG concentration and deliver appropriate signals in terms of B-cell progression to plasma cells or regulating plasma cell IgG synthesis. For more than two decades, this presumption has motivated the coapplication of immunosuppressants with plasmapheresis to inhibit the anticipated rebound in antibody synthesis: “In order to control the possible increase in antibody synthesis, it is now generally accepted that immunosuppressive drugs should accompany plasma exchange.”21 It is not our intent to review the diverse data that have been cited to support or oppose this hypothesis (see Charlton and Schindhelm22 ), but it is fair to state that the evidences to favor this phenomenon have not been compelling over time. By the mid 1980s, a review of apheresis technologies stated, “Controversy surrounds the practice of combining cytotoxic drug therapy with plasmapheresis to prevent rapid resynthesis of antibody, so-called antibody rebound. ... [T]here is no general agreement on this finding.” 23 Yet, the practice has continued to be widely followed from that earlier era down to the present.

In the mid-1980s, Charlton et al22,24-26 conducted a series of excellent studies that regrettably did not find their way into the mainstream hematology literature. These examined changes in IgG synthesis using a rabbit plasmapheresis model, using for the first time appropriate compartmental pharmacokinetic models to derive IgG biosynthetic rates. With a 60% plasma IgG removal (whole body change of −24%), a reduction in catabolism of 30% was shown, in accord with the Brambell model,4 but no impact on IgG synthesis could be detected during the return to normal plasma concentrations over the ensuing 5 days. The power of this conclusion was limited by the relatively minor impact on total IgG and a ±50% range in biosynthesis determinations. Nevertheless, this depletion was in the range of human IgG depletions by plasmapheresis and the lack of an aggressive rebound of oversynthesis was clear. They additionally showed that immunoadsorption to remove specific antibody could lead to release of small amounts of solid-phase antigen as an immune booster that could induce an artifactual antibody “rebound.” 26 We are unaware of any effort since this time to address the role of IgG concentration to mediate an “immunoregulatory feedback” on IgG biosynthesis, although it was cited as an active mechanism in a prominent review of IgG metabolism as recently as 1990.19

Scientifically, the practical limits on IgG depletion via plasmapheresis and the transient nature of the reduction put limits on the power of this procedure to address the question of a feedback mechanism in IgG synthesis. By contrast, the near 10-fold difference in steady-state IgG concentration in the FcRp-deficient mice presents an opportunity to address this question definitively. Concomitant with pharmacokinetic modeling to demonstrate the role of the Brambell receptor in protection of IgG from catabolism, we measured IgG biosynthetic rates in matched, inbred mice with different endogenous levels of IgG.12 If biosynthesis (q; Eq. 1) is constant, the null hypothesis, then changes in Css should be inversely related to changes in k10 . As shown in Table 1, IgG levels in FcRp−/− mice decreased approximately eight-fold concurrent with a comparable increase in catabolic rate (k10 ), whereas IgM16 and IgA,12 unrelated to FcRB action, were unaffected (not shown). The biosynthetic rate q = k10 Css (from Eq. 1) is shown in the final column. IgG biosynthesis was not significantly different between the wild-type and FcRp−/− mice despite the extreme difference in IgG levels. This confirms that the differences in IgG concentrations are fully explained by the difference in catabolic rates. We reject the alternative hypothesis that IgG synthesis is higher in low-IgG mice, and we conclude that IgG levels do not exert a feedback on IgG biosynthetic rates.

Analysis of IgG Biosynthetic Rates in Mice Differing in IgG Levels Because of Increased Catabolism

| . | t (days) . | k10 (day−1) . | CSS [IgG] (μg/mL) . | q (μg/mL/d) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 3.78 | 0.18 ± .01 | 2200 ± 100 | 396 ± 28 |

| FcRp knockout | 0.52 | 1.34 ± .06 | 260 ± 30 | 348 ± 43 |

| NS; P > .1 |

| . | t (days) . | k10 (day−1) . | CSS [IgG] (μg/mL) . | q (μg/mL/d) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 3.78 | 0.18 ± .01 | 2200 ± 100 | 396 ± 28 |

| FcRp knockout | 0.52 | 1.34 ± .06 | 260 ± 30 | 348 ± 43 |

| NS; P > .1 |

The listed t value is for the catabolic t , not the β t . Errors on k10 are derived from the fitting program of the average data and errors on the [IgG] are derived from the individual mouse plasma levels. There were 5 mice per group. The standard error of the product (q = k10 CSS) is derived by standard formulas. Statistical significance is determined by the two-tailed Student's t-test. Derived from Junghans and Anderson.12

Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

Because this conclusion flies in the face of long-held presumptions, it is important to highlight the technical performance of this study. Mice of different strains can have different basal metabolic rates, as reflected in albumin catabolism differences. Such differences in total protein catabolism in mixed background (C57BL/6 × 129/Ola) β2m-knockout and wild-type mice complicated comparisons of catabolism and synthesis of IgG,9,12 but these discrepancies disappeared when normalized to albumin catabolic rates.12 Thus, it proved important to use inbred mice, as in Table 1. However, even with inbred mice, a controlled pathogen environment is crucial for comparisons of biosynthesis and catabolism, due to direct effects of pathogen as a biosynthetic stimulus, as shown in dramatic fashion by Sell and Fahey in 1965.5 Furthermore, misleading conclusions on catabolism and synthesis of IgG and its fragments arise from use of commonly applied β-rate constants instead of catabolic rate constants, as pointed out by Waldmann and Strober in 19698 and as reiterated since.3,19 Our mice were born and raised in the same facilities and we used formal two-compartment pharmacokinetic modeling to derive actual catabolic rates.12 The use of control and knockout mice from different colonies and reference to β rather than catabolic rate constants explain the differences in apparent synthetic rates reported in another study9 (V. Ghetie, personal communication). Similarly, prior conclusions for “rebound” synthesis after pheresis (Bystryn et al20 and other studies) were not based on pharmacokinetic modeling. We conclude that early inferences of rebound can be explained by volume shift effects, IgG return to plasma from extravascular and lymphatic reservoirs, diminished catabolism (by the Brambell model), solid-phase antigen-release during immunoadsorption, and variability in IgG concentration assays.

We thus accept the null hypothesis — that IgG synthesis is unrelated to IgG levels — and conclude that there is no “immunoregulatory feedback” of IgG concentration to regulate IgG biosynthesis; all synthesis is related to the immune stimulus in the response to antigens. Finally, in terms of therapeutic interventions, with no mechanism for autoregulation of IgG concentration, there is no basis for concern of a “rebound” of excess IgG synthesis postpheresis: synthesis will continue just as it was before the procedure. Furthermore, this implicitly calls into question one of the theoretical rationales cited for the practice of coapplication of immunosuppression. On the other hand, immunosuppressants will continue to have an important general role in inhibiting synthesis of autoantibodies, but the particular timing of their application in proximity to pheresis should not be considered related to any “rebound” of IgG synthesis. The debate of the relative merits of immunosuppression versus plasmapheresis or their combination27 may thus proceed independent of concern for any plasmapheresis-induced rebound phenomena.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I thank Drs Walter Dzik, Derry Roopenian, and Bruce McLeod for useful discussions.

Address reprint requests to R.P. Junghans, PhD, MD, Harvard Institutes of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 77 Avenue Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02215.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal