Abstract

Mammalian globin gene expression is activated through NF-E2 elements recognized by basic-leucine zipper proteins of the AP-1 superfamily. The specificity of NF-E2 DNA binding is determined by several nucleotides adjacent to a core AP-1 motif, comprising a recognition site for transcription factors of the Maf subfamily. Earlier work proposed that p18(MafK) forms a heterodimer with hematopoietic-specific protein p45 NF-E2 to activate transcription through NF-E2 sites. However, there was no direct evidence that p18(MafK) serves this function in vivo; in fact, mice lacking p18(MafK) have no phenotype. Here we describe a novel cDNA clone that encodes the human homolog of chicken MafG. Human MafG heterodimerizes with p45 NF-E2 and binds DNA with specificity identical to that of purified NF-E2 DNA binding activity. A tethered heterodimer of p45 and MafG is fully functional in supporting expression of α- and β-globin, and in promoting erythroid differentiation in CB3, a p45-deficient mouse erythroleukemia cell line. These results indicate that human MafG can serve as a functional partner for p45 NF-E2, and suggest that the p45/MafG heterodimer plays a role in the regulation of erythropoiesis.

THE ANALYSIS of mammalian globin gene transcription serves as a paradigm for understanding tissue-specific and developmental regulation of gene expression. The erythroid-specific activation of globin genes is mediated by unique regulatory elements which coincide with DNase I hypersensitive sites, termed locus control regions (LCRs).1,2 The LCRs contain core units of about 200 to 300 bp which are comprised of binding motifs for general and tissue-specific transcription factors.3 Among these, NF-E2 motifs have been shown to mediate a tissue-specific enhancer activity.4-11 NF-E2 sites act, at least in part, to promote opening of chromatin structure throughout the globin loci, potentiating gene expression.11-14

Although NF-E2 sites contain a core AP-1 motif, early experiments indicated that a G residue outside of the AP-1 consensus sequence was crucial for LCR-mediated gene expression. This led to the functional definition of the NF-E2 element as GCTGA(G/C)TCA (AP-1 motif underlined; critical G residue in italics).5,6,8,15 A hematopoietic-specific gel shift complex was identified that similarly required the upstream residue for protein-DNA interaction and, thus, correlated with the functional NF-E2 site.5,15 16

NF-E2 DNA binding activity was purified to near-homogeneity from mouse erythroleukemia (MEL) cells using the gel-shift assay.16,17 Polypeptides of approximately 45 kD (two major, several minor bands) and 18 kD (one major, several minor bands) were highly enriched in the final purification fractions16,17 (and N.C.A. unpublished data, September 1992). Partial amino acid sequence analysis was performed on material from each of these molecular-weight classes and two corresponding cDNA clones were obtained through the use of degenerate oligonucleotide probes.16,17 When coexpressed, the protein products of these cDNA clones generated NF-E2 DNA binding activity indistinguishable from the gel-shift complex previously noted. In this way, NF-E2 DNA binding activity from MEL cells was shown to consist of a heterodimer containing a 45-kD subunit (p45) and an 18-kD subunit (p18).16-18 Both subunits are members of the AP-1–like superfamily of nuclear basic-leucine zipper (bZIP) proteins.

p45 is expressed almost exclusively in hematopoietic cells.16,18,19 It shows strong homology to the products of the Drosophila cnc and Caenorhabditis elegans skn-1 genes.20,21 Subsequently, other related proteins have been characterized, including the ubiquitous factors NRF1/LCR-F1/TCF11, NRF2/ECH, Bach1, and the tissue-restricted factor Bach2.10,22-27 Extensive structure-function analysis of p45 has not yet been reported, but deletion mutations have shown that an activation domain is located in the amino-terminal portion of the protein.28 29

p18, also known as MafK, is expressed in most, if not all tissues.17,30-32 p18(MafK) belongs to the Maf protein family, of which the prototype is v-Maf, which induces tumors in chickens and transforms avian fibroblasts.33 Maf proteins may be subdivided into large and small classes. The cellular homolog of v-Maf, c-Maf, as well as MafB/kreisler and NRL, belong to a subgroup of large Maf proteins, which have activation domains at their amino-termini.33-36 Each of these has been shown to play an important role in differentiation: v-Maf disrupts normal differentiation and transforms cells,33 c-Maf controls T-cell–specific expression of the interleukin-4 gene,37 MafB/kreisler acts in development of the central nervous system,35 and NRL regulates expression of retinal gene products.34,38,39 MafB has also been implicated in the negative regulation of erythroid differentiation through interactions with Ets-1.40

In contrast, the small Maf proteins, which are more closely related to mouse p18(MafK), include chicken MafF, MafG, and MafK gene products.30,31,41 These proteins lack distinct activation domains. No tissue-specific functions have been assigned to the small Mafs, aside from the putative role of p18(MafK) in erythroid gene expression, as discussed below.17 42

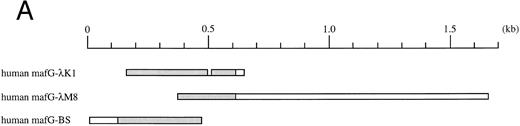

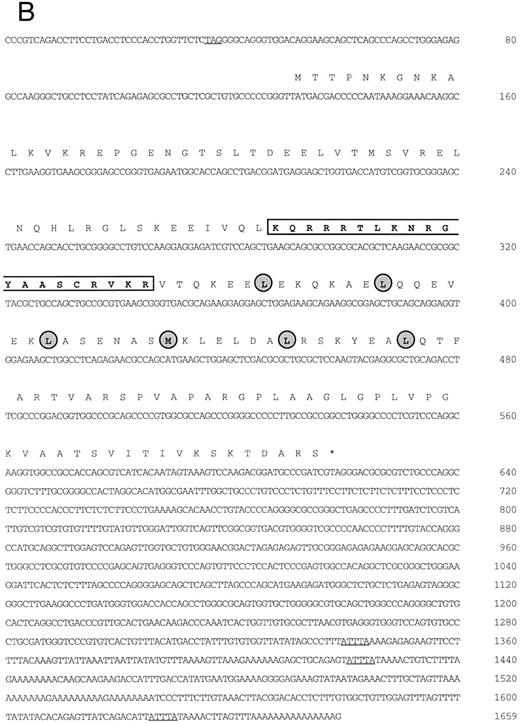

(A) Schematic representation of human MafG cDNAs. Coding sequences are shaded. (B) cDNA sequence of human MafG. The basic domain is boxed and lightly shaded. Dark shaded circles indicate the leucine zipper. An in-frame, upstream termination codon in the 5′UTR, and putative 3′UTR AUUUA mRNA degradation sequences55 are underlined.

(C) Comparison of human MafG to related small Maf proteins. Nonconserved amino acids are shaded. Numbers in parentheses represent amino acid positions. The basic region is indicated with a black bar; locations of leucine zipper residues are marked with black dots.

(A) Schematic representation of human MafG cDNAs. Coding sequences are shaded. (B) cDNA sequence of human MafG. The basic domain is boxed and lightly shaded. Dark shaded circles indicate the leucine zipper. An in-frame, upstream termination codon in the 5′UTR, and putative 3′UTR AUUUA mRNA degradation sequences55 are underlined.

(C) Comparison of human MafG to related small Maf proteins. Nonconserved amino acids are shaded. Numbers in parentheses represent amino acid positions. The basic region is indicated with a black bar; locations of leucine zipper residues are marked with black dots.

Several lines of evidence have supported the hypothesis that p45/p18(MafK) heterodimer is responsible for activation of murine globin gene expression through NF-E2 sites. First, p45 is expressed almost exclusively in blood-forming cells,16,18,19 consistent with the erythroid-specific nature of chromatin changes mediated by LCR NF-E2 sites.11-14 Recombinant p45/p18(MafK) heterodimer is able to open the chromatin structure of the β-globin locus in vitro, with the p45 subunit necessary to bind to chromatin, but not to naked DNA.13 Second, p18(MafK) confers a stringent DNA-binding specificity to the complex, corresponding to the functional NF-E2 consensus sequence described above.17 In fact, purification of NF-E2 DNA binding activity from MEL cells allowed a more detailed binding site characterization to be done and an 11-bp consensus sequence, (T/C)GCTGA(G/C)TCA(T/C), was shown to be important for recognition by the p45/p18(MafK) complex in vitro.16 17

Proof of the activity of p45/p18(MafK) in vivo has been more difficult to come by. A useful tool has been found in the mutant erythroleukemia cell line, CB3, which contains a retroviral insertion disrupting expression of p45.43 This cell line produces no detectable p45 protein and expresses very low levels of α- and β-globin. Forced expression of p45 restores globin gene expression43 and forced expression of a tethered molecule, which covalently links p45 to p18(MafK), recapitulates this rescue.28 Although LCR-F1 has been shown to interact with small Maf proteins in vitro,44 a similar molecule tethering p18(MafK) to LCR-F1 fails to rescue.28 These experiments strongly support the role of p45 in globin gene expression, at least in the context of this erythroleukemia cell line, but only indirectly support the role of p18(MafK). One experiment does address the role of p18(MafK) directly: p18(MafK) has been shown to induce erythroleukemia cell differentiation when overexpressed from a conditional promoter.42 However, the possibility remains that p18(MafK) is one of several proteins which may serve as partners for p45 in mouse cells in vivo. This possibility has been suggested previously by Igarashi et al,31 who found that all three chicken small Maf proteins (MafK, MafF, and MafG) can heterodimerize with murine p45 in vitro, whereas large Maf proteins cannot. They did not, however, directly examine the potential of these small Maf proteins to activate erythroid transcription.

Recent experiments support the notion that p18(MafK) is not the only factor which can dimerize with p45 to act through NF-E2 sites in the LCR-mediated regulation of globin gene expression. Gene targeting of the p18(MafK) locus yielded p18(MafK)-null mice which were indistinguishable from their wild-type litter mates.45 This indicates that the p18(MafK) subunit is dispensable in vivo. To date, only proteins of the Maf family are known to have the same DNA binding specificity as seen in the functional experiments defining the upstream nucleotide requirements of the NF-E2 element. This leads to the conclusion that if p18(MafK) is not the exclusive (or even major) partner in NF-E2 regulation, another Maf protein is the most likely substitute.

To find novel mammalian Maf proteins, we screened human cDNA libraries at low stringency with a mouse p18(MafK) probe. By using this approach we have cloned a new, ubiquitously expressed human gene that is highly homologous to chicken MafG. In this report we show that human MafG has properties, in vitro and in vivo, indistinguishable from those of murine p18(MafK). A tethered p45/MafG heterodimer fully rescues globin gene expression in CB3 cells and potentiates other aspects of erythroid differentiation. Thus, MafG is fully functional as a partner for p45 in regulating globin gene expression. Intriguingly, no cDNA sequence encoding a human homolog of p18(MafK) or MafF has been reported in the nucleic acids sequence database. This raises the possibility that MafG may be the major (or even exclusive) small Maf protein acting through LCR NF-E2 sites in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and transfection.COS-7 (monkey kidney), MEL (murine erythroleukemia clone 745 GM86), CB3 (p45-deficient murine erythroleukemia43 ), and MC8 (murine mast cell46 ) cells were passaged in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. K562 (human chronic myelogenous leukemia) cells and HEL (human erythroleukemia) cells were passaged in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Dami (human megakaryocytic) cells were passaged in a special media as described,47 but supplemented with 20% horse serum. Transient transfection of COS-7 cells with the pMT2 expression constructs was performed by the diethylaminoethyl (DEAE)-dextran procedure as described previously.16 Stable transfection of CB3 cells was performed as follows: 1.5 × 107 cells were electroporated with 20 μg of pEF1αneo constructs using a BioRad Gene Pulser II (Hercules, CA) at 290 mV and 950 μF. Stably transfected cells were selected in 1.5 mg/mL Geneticin (G418; GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD).

Isolation of MafG cDNA clones.A λgt11 cDNA library prepared from K562 mRNA (obtained from Stuart Orkin, Children's Hospital) was screened at low stringency with a mouse p18(MafK) cDNA probe17 using standard procedures. One positive clone was fully analyzed. This cDNA clone (λK1) was then used to probe a human muscle cDNA library (obtained from Louis Kunkel, Children's Hospital) and a human genomic library (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) at high stringency. The cDNA clone isolated from the human muscle cDNA library (λM8) contained additional 3′UTR sequence, but lacked the 5′ end of the MAFG coding sequence. A genomic clone, which will be described elsewhere, contained upstream sequences (V. Blank, J.H.M. Knoll, and N.C. Andrews, in preparation). A portion of this clone corresponded to an expressed sequence tag sequence (GenBank accession no. D3139048), allowing us to deduce the position of the 5′UTR and the likely initiation codon region of human MafG. Using reverse transcription followed by the polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with primers MafG-A6 (5′-GACTGGATCCTGACCTCCCACCTGGTGCTCTA-3′ ) and MafG-A5 (5′-GTCTGCAGCGCCTCGTACTT-3′ ) we obtained a cDNA clone (BS) from K562 RNA comprising the 5′UTR and part of the coding region. The overlapping BS and λM8 clones were assembled to generate a cDNA containing the entire coding sequence using an Sac I restriction enzyme site (position 438 of MAFG cDNA) common to both clones. The DNA sequence of this construct was determined using Sequenase (United States Biochemical, Cleveland, OH) according to the manufacturer's instructions. These cDNA clones are summarized in Fig 1A.

Plasmid constructs.The MAFG cDNA (position 15-1659) was subcloned into the EcoRI site of the pMT2 expression vector. A pMT2p45 expression construct has been previously described.16 The tethered p45/MafG cDNA was constructed by two sequential rounds of the PCR using overlap extension. The following primers were used in the first round of PCR: p45-F1L (5′-ATAGAATGCGGCCGCGAATTCTGGCACAGTAGGATGCCCCCGT-3′ ), p45-R1L (5′-GCCGCTCCCACCTCCAGAACCCCCGCCGGATCCACCCCCAGATCTATCTGTAGCCTCCATTTTGGT-3′ ), MafG-F2L (5′-GGGGTTCTGGAGGTGGGAGCGGCGGAGGGTCCGGCGGA-A G A T C T A T G A C G A C C C C C A A T A A A G G A A A - 3 ;pr ) , M a f G - R 2 L -(5′-ATAGAATGCGGCCGCGAATTCCTACGATCGGGCATCCGTCTT-3′ ). The primers contain restriction sites to facilitate subcloning. Both amplification products of the first round were used in a second round of PCR with primers p45-F1L and MafG-R2L to amplify a composite cDNA coding for a tethered heterodimer. The resulting tethered heterodimer contains the carboxy-terminus of p45 fused to the amino-terminus of MafG via a flexible peptide linker [RS(GGGS)4GGRS]. This procedure was similar to that used previously to prepare other tethered heterodimer transcription factors.28,49 The tethered p45/mafG cDNA was subcloned into the EcoRI site of pEF1αneo (from Stuart Orkin). The pEF1αneo expression vector is driven by the promoter of the human elongation factor 1α gene50 and contains the neomycin resistance gene as a selectable marker.

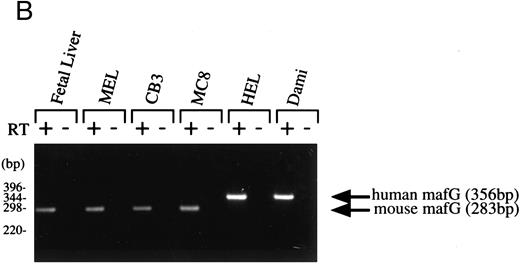

RNA expression analysis.Northern blots Human I, Human IV, and Fetal II from Clontech were used to analyze tissue expression of MafG. Each blot carries approximately 2 μg of poly (A)+ RNA per lane. Hybridization was performed with Quikhyb (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The probe used was a 0.4-kb Pvu I-Msc I fragment of the MafG cDNA (nucleotides 612-1016). RT-PCR was performed using the Superscript System (GIBCO-BRL). Specific primer pairs were used for amplification of human cDNA (hmafG-F 5′-GGCACATGG-C G A A T T T G G C T G C C C - 3 ;pr , h m a f G - R 5 ;pr - C A C T C G G G A G T G -GAGGGAACACTG-3′ ) and mouse cDNA (mmafG-F-5′-GGT-G T C A C T G T T T A C A T G A C C - 3 ;pr , m m a f G - R 5 ;pr - C T A A A C T C C A -ACAGCCACAGC-3′ ) (mouse sequence is our unpublished data). The expected products are 356 bp (human) and 283 bp (mouse) in size. The PCR protocol was as follows: 2 minutes of denaturation at 94°C, followed by 30 three-step cycles of 45 seconds of denaturation at 94°C, 30 seconds of annealing at 55°C, and 45 seconds of elongation at 72°C.

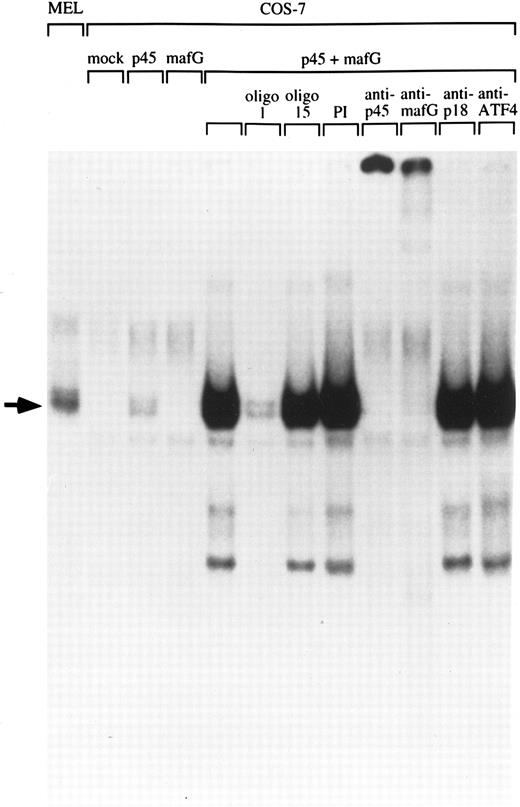

Gel-shift assays.Gel-shift assays were performed as described previously.51 Oligonucleotide 1 contains the NF-E2 binding site from the porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD) promoter16; this was used as a probe. Preimmune (PI) or immune sera were added to the reactions, as indicated, at a concentration of 1 μL per 15 μL total reaction volume. Anti-p45 and anti-p18(MafK) antisera have been described previously.16 17 Anti-MafG antiserum was prepared as described below. The unrelated anti-ATF4 antiserum was prepared by the same method against a glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein containing murine ATF4 sequence (L. Montross and N.C. Andrews, unpublished data). Unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides 1 to 16 were identical to those described previously16; these were added to a final concentration of 0.6 ng/μL.

Preparation of MafG antiserum.Female New Zealand White rabbits were immunized with a GST fusion protein containing amino acids 1-162 of human MafG. Antiserum was tested in parallel with preimmune serum to confirm the specificity to MafG.

RNase protection.MEL cells, CB3 cells, and stably transfected CB3 cells (see above) were induced to differentiate by dilution to 105 cells/mL and incubation in the presence of 1.8% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 3 days. Cell samples were split to prepare nuclear extracts as previously described52 and to isolate total RNA using RNA Stat-60 according the protocol of the manufacturer (LEEDO Medical Laboratories, Houston, TX). The RNase protection assay was performed according to standard procedures.53 Riboprobes specific for mouse α-, βmajor-globin, and γ-actin transcripts have been described.54

Nucleotide sequence accession number.The cDNA sequence of human MAFG has been submitted to the GenBank database. The accession number is U84249.

RESULTS

Isolation of a human MafG cDNA.We screened a K562 cDNA library at low stringency with a mouse p18(MafK) probe in an attempt to isolate new members of the Maf protein family that might participate in erythroid gene expression. A single clone was obtained (λK1) which showed strong homology to chicken MafG. This cDNA was missing the 5′ end and contained a small internal deletion. A longer cDNA that contained 3′UTR sequences (λM8) was isolated from a human muscle cDNA library, but this clone also lacked 5′ terminal sequences. We next isolated a genomic clone and identified an expressed sequence tag sequence which provided sequence information that allowed us to determine which sequences encoded the 5′UTR and the initiation codon. Using RT-PCR, we obtained a cDNA clone comprising the 5′UTR and part of the coding region (BS). A summary of all cDNA clones is provided in Fig 1A. The overlapping clones were assembled using suitable restriction enzyme cleavage sites. The composite cDNA codes for a new human bZIP transcription factor were designated human MafG because of its close relationship (93.8% identity) to chicken MafG41 (Fig 1B). An in-frame termination codon is present upstream of the predicted start codon of human MAFG, thereby defining an open reading frame of 162 amino acids. Putative mRNA-destabilizing sequences (AUUUA55 ) are present in the 3′UTR and are conserved among human, mouse, chicken, and rat mafG mRNAs41 (and unpublished data, 1996; GenBank accession numbers H31496, H3149756). A comparison of the protein sequences of human MafG and other small Maf proteins shows strong conservation of basic and leucine zipper domains (Fig 1C). There are two regions unique to MafG: a proline-rich hydrophobic stretch of 15 amino acids adjacent to the leucine zipper and 6 amino acids at the carboxy-terminus.

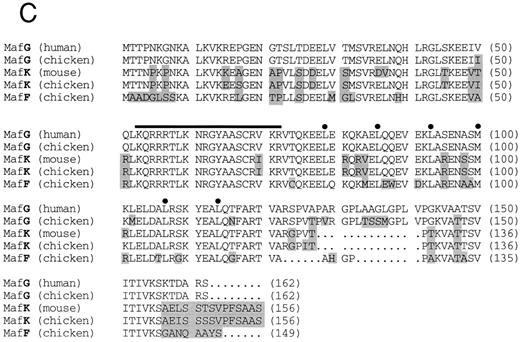

Expression pattern of human MAFG transcripts in various tissues and cell lines. (A) MAFG mRNA expression in human adult and fetal tissues. Northern blots were prepared by Clontech with approximately 2 μg of poly(A)+ RNA from each tissue. The identities of the tissues are shown at the top of each lane; “P. Blood Leukocytes” indicates “peripheral blood leukocytes.” RNA size markers are shown on the left. (B) RT-PCR amplification of total RNA from mouse fetal liver (d15), mouse cell lines (MEL, CB3, MC8), and human cell lines (HEL, Dami). Each RNA sample was processed with (+) and without (−) RT. Arrows on the right indicate specific human (356 bp) and mouse (283 bp) MafG amplification products. DNA size markers are shown on the left.

Expression pattern of human MAFG transcripts in various tissues and cell lines. (A) MAFG mRNA expression in human adult and fetal tissues. Northern blots were prepared by Clontech with approximately 2 μg of poly(A)+ RNA from each tissue. The identities of the tissues are shown at the top of each lane; “P. Blood Leukocytes” indicates “peripheral blood leukocytes.” RNA size markers are shown on the left. (B) RT-PCR amplification of total RNA from mouse fetal liver (d15), mouse cell lines (MEL, CB3, MC8), and human cell lines (HEL, Dami). Each RNA sample was processed with (+) and without (−) RT. Arrows on the right indicate specific human (356 bp) and mouse (283 bp) MafG amplification products. DNA size markers are shown on the left.

Expression pattern of human MafG.We next investigated the tissue distribution of human MafG by Northern blot and RT-PCR analysis. The high degree of homology among Maf family members precluded using coding sequence as a probe; instead, a highly specific probe was derived from the 3′UTR. This probe detected a major transcript of about 5.5 kb (Fig 2A). The level of expression was very low in all tissues, requiring 2 days of autoradiography with Kodak Biomax film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) to detect the signal. We believe that the discrepancy between the sizes of the cloned cDNA (1.66 kb) and the hybridizing transcript is most likely explained by as yet uncharacterized 3′UTR sequences. This conclusion is supported by the fact that no consensus polyadenylation site was found in the cDNA. Human MAFG mRNA was expressed in all adult and fetal tissues examined, at varying levels. Expression was particularly low in kidney, lung, and peripheral blood leukocytes.

If MafG interacts functionally with p45 NF-E2, it must be expressed in the same cell types. p45 is expressed almost exclusively in hematopoietic progenitors and myeloid cells of the erythroid, megakaryocytic, granulocyte, and mast cell lineages.16,18,19 57 Clearly MafG is expressed in some hematopoietic cells, as its cDNA was isolated from a K562 library. To examine other hematopoietic cell lines, oligonucleotide primers were designed to specifically amplify MAFG from human cells and from mouse cells (mouse mafG sequence is our unpublished data). Thus, we showed that MAFG transcripts were present in a human megakaryocytic (Dami) and erythroleukemia (HEL) cell lines, mouse erythroleukemia cell lines (MEL and CB3), and mouse mast cells (MC8) (Fig 2B). mafG mRNA was also expressed in day 15 mouse fetal liver, the major erythropoietic organ at that developmental stage. Thus, MafG is widely expressed and its expression pattern overlaps that of p45 NF-E2. We can conclude that MafG would be available in both mouse cells and human cells to act in conjunction with p45 to regulate gene expression.

Human MafG interacts with p45 NF-E2.Chicken MafG has been previously shown to heterodimerize with p45 NF-E2 in vitro.31 To determine whether human MafG could form functional heterodimers with p45, we transiently transfected COS-7 cells with constructs coding for human MafG and mouse p45 NF-E2, and examined DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts using a gel-shift assay (Fig 3). Mock-transfected COS-7 cells and cells transfected solely with a construct coding for MafG did not show any specific NF-E2 binding activity. Transfection of p45 NF-E2 cDNA alone gave rise to a weak binding activity, presumably due to interaction of p45 NF-E2 with an endogenous monkey Maf protein. Cotransfection of MafG and p45 NF-E2 resulted in a strong NF-E2–like gel shift band, that comigrates with the NF-E2 complex detected in MEL cells. This result shows that MafG is able to heterodimerize with p45 to bind DNA. The addition of an unlabeled oligonucleotide duplex with the same NF-E2 site (oligo 1) completely abolishes the binding. A mutant NF-E2 binding site oligonucleotide duplex that does not bind NF-E2 (oligo 15) did not compete for p45/MafG binding.

Heterodimerization of MafG with p45 NF-E2. A NF-E2 DNA-binding site derived from the human PBGD promoter was used as a probe to detect NF-E2 DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts from MEL cells and COS-7 cells transfected with different cDNAs. Competitor oligonucleotides (1 or 15), preimmune serum (PI) or anti-MafG, anti-p45, anti-p18, or anti-ATF4 serum was added to the reaction mix as indicated. Oligonucleotide 1 binds both NF-E2; oligonucleotide 15 contains a single base-pair mutation that blocks NF-E2 binding.16 An arrow indicates the position of NF-E2 and p45/MafG complexes.

Heterodimerization of MafG with p45 NF-E2. A NF-E2 DNA-binding site derived from the human PBGD promoter was used as a probe to detect NF-E2 DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts from MEL cells and COS-7 cells transfected with different cDNAs. Competitor oligonucleotides (1 or 15), preimmune serum (PI) or anti-MafG, anti-p45, anti-p18, or anti-ATF4 serum was added to the reaction mix as indicated. Oligonucleotide 1 binds both NF-E2; oligonucleotide 15 contains a single base-pair mutation that blocks NF-E2 binding.16 An arrow indicates the position of NF-E2 and p45/MafG complexes.

To facilitate biochemical studies of MafG complexes, we prepared a high-titer polyclonal antiserum against a GST fusion protein containing full-length human MafG. In extracts from COS-7 cells cotransfected with p45 and MafG cDNAs, both this antiserum and an anti-p45 antiserum disrupted the gel-shift complex, confirming that it contained both p45 and MafG (Fig 3). In contrast, antisera raised against murine p18(MafK) and ATF4 had no effect. These results show that MafG forms heterodimers with p45 NF-E2 resulting in complexes indistinguishable from those of the p45/p18(MafK) heterodimer.

We also found that MafG is able to bind to DNA as a homodimer in gel-shift experiments using a palindromic binding site probe consisting of two Maf half-sites (data not shown). p18(MafK) is also known to bind DNA as a homodimer.17 32

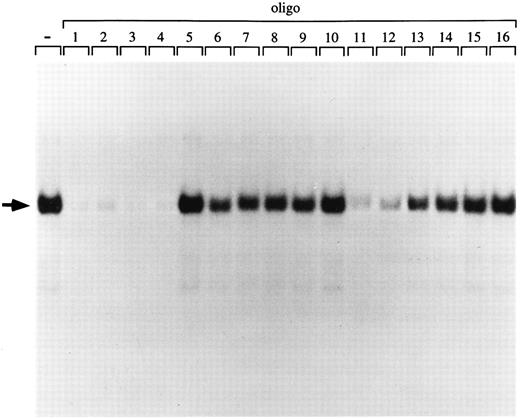

p45/MafG has the same DNA binding specificity as purified NF-E2 and p45/p18(MafK).To further characterize the binding specificity of the p45/MafG heterodimer, we used a series of closely related oligonucleotides to compete for binding to an NF-E2 site probe (Fig 4). Oligonucleotides corresponding to NF-E2 sites found in the human α-globin LCR (oligos 2 and 3), the chicken β-globin enhancer (oligo 4), as well as two mutant PBGD promoter sites (oligos 11 and 12) competed very well. As described above, it has been shown that a G residue outside the AP-1 core is important for NF-E2 enhancer activity.6,8,58 Accordingly, an oligonucleotide mutated at this residue (oligo 15) does not compete for binding of the p45/MafG complex (Figs 3 and 4). In summary, the p45/MafG binding pattern is indistinguishable from that of purified murine NF-E2 using the same set of oligonucleotide binding sites.16

DNA-binding specificity of the p45/MafG heterodimer. An NF-E2 DNA-binding site derived from the human PBGD promoter was used as a probe to detect NF-E2 DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts from COS-7 cells cotransfected with expression constructs coding for p45 NF-E2 and MafG. A series of wild-type and mutant NF-E2 binding site oligonucleotides were used as competitors. The sequences of competitor oligonucleotides 1 to 16 have been described previously.16

DNA-binding specificity of the p45/MafG heterodimer. An NF-E2 DNA-binding site derived from the human PBGD promoter was used as a probe to detect NF-E2 DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts from COS-7 cells cotransfected with expression constructs coding for p45 NF-E2 and MafG. A series of wild-type and mutant NF-E2 binding site oligonucleotides were used as competitors. The sequences of competitor oligonucleotides 1 to 16 have been described previously.16

We compared the rates at which p45/p18(MafK) and p45/MafG complexes release radiolabeled oligonucleotide probe in the presence of added cold competitor. The ‘off rates’ for the two complexes were indistinguishable (data not shown).

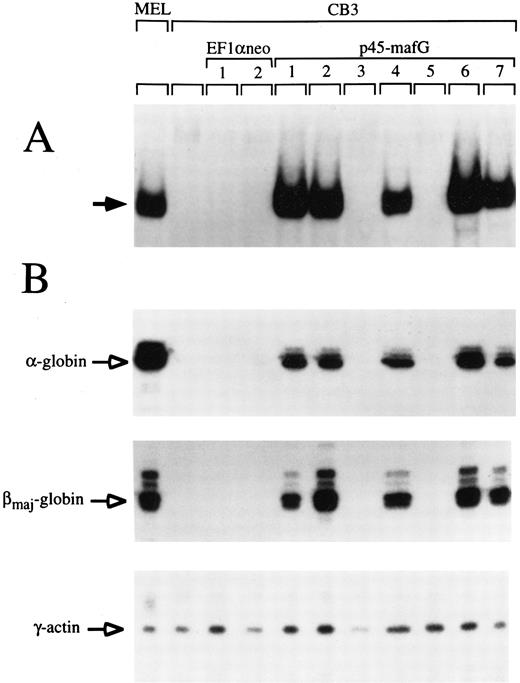

A tethered p45/MafG heterodimer rescues α- and β-globin expression in CB3 cells.The similarity of p45/MafG DNA binding specificity to that of p45/p18(MafK) suggested that the p45/MafG complex might be functionally interchangeable with p45/p18(MafK). To determine whether p45/MafG could activate globin gene expression in vivo, we chose mouse CB3 cells as an assay system. CB3 is a mutant mouse erythroleukemia cell line that does not express p45.43 Due to the absence of p45, α- and β-globin expression levels are very low in DMSO-induced CB3 cells, but can be partially restored upon transfection of constructs coding for p45 NF-E2 or covalently linked p45/p18(MafK).28 43 To test the function of p45/MafG, we constructed a cDNA encoding a tethered heterodimer in which p45 and MafG are joined by a glycine- and serine-rich linker segment. This construct was stably transfected into CB3 cells. Clones were selected in the presence of Geneticin (G418; GIBCO-BRL) and screened for tethered p45/MafG expression by gel-shift assay using an NF-E2 site probe. We used nuclear extracts from MEL cells as a positive control. CB3 cells, or CB3 cells transfected with expression vector alone, served as negative controls. As shown in Fig 5A, several clones transfected with the p45/MafG construct showed high-level expression of the heterodimer. The characteristic gel-shift band migrated slightly slower than that of the NF-E2 DNA binding activity in MEL cells, presumably because of the additional linker peptide.

A tethered p45/MafG heterodimer rescues α- and β-globin expression in the CB3 cell line. (A) Gel-shift assays were performed using nuclear extracts from MEL cells, untransfected CB3 cells, and CB3 cells stably transfected with either expression vector (EF1αneo) alone, or expression vector coding for a tethered p45/MafG heterodimer (see notations at top of lanes). An NF-E2 DNA-binding site derived from the human PBGD deaminase promoter was used as a probe. The arrow indicates the bound complex. The complex formed from p45/MafG tethered heterodimer migrates slightly slower than NF-E2 in MEL cells, presumably because of the mass of the linker segment. Not all clones transfected with the construct coding for p45/MafG express the heterodimer. (B) RNase protection analysis of cell lines described above. Probes were specific for mouse α- and βmajor-globin transcripts. γ-Actin was used as an internal control.

A tethered p45/MafG heterodimer rescues α- and β-globin expression in the CB3 cell line. (A) Gel-shift assays were performed using nuclear extracts from MEL cells, untransfected CB3 cells, and CB3 cells stably transfected with either expression vector (EF1αneo) alone, or expression vector coding for a tethered p45/MafG heterodimer (see notations at top of lanes). An NF-E2 DNA-binding site derived from the human PBGD deaminase promoter was used as a probe. The arrow indicates the bound complex. The complex formed from p45/MafG tethered heterodimer migrates slightly slower than NF-E2 in MEL cells, presumably because of the mass of the linker segment. Not all clones transfected with the construct coding for p45/MafG express the heterodimer. (B) RNase protection analysis of cell lines described above. Probes were specific for mouse α- and βmajor-globin transcripts. γ-Actin was used as an internal control.

To assess the functional capability of the expressed heterodimers, we performed RNase protection assays to see whether these cell clones expressed α- or βmajor-globin upon DMSO-induced differentiation (Fig 5B). γ-Actin was used as a internal control. All clones that tested positive for p45/MafG expression showed high levels of α- and β-globin transcripts upon induction. Quantitative analysis of phosphorimager signals from Northern blots showed a 20- to 40-fold induction of β-globin in these clones (data not shown). These results indicate that the p45/MafG heterodimer is able to activate endogenous globin gene expression in CB3 cells. In parallel experiments, we found that the activity of tethered p45/MafG was indistinguishable from that of tethered p45/p18(MafK) (data not shown). Thus, MafG can act as a functional partner for p45 NF-E2 in the expression of endogenous erythroid-specific genes. Additionally, we examined expression of erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) mRNA in CB3 cells that express high levels of the p45/MafG complex and found that levels increased about threefold with DMSO induction (data not shown). About half of the clones expressing p45/MafG showed elevated globin and EpoR transcript levels even without DMSO induction. This indicates that forced expression of p45/MafG activates an erythroid differentiation program in CB3 cells.

DISCUSSION

NF-E2 regulatory elements found in the tissue-specific DNase I hypersensitive sites upstream of α- and β-globin gene clusters play a major role in activation of globin gene expression.4-11,58 The mechanism of action of these sites is not entirely understood, but it appears that binding of specific transcription factors facilitates chromatin remodeling and opening of the globin loci.11-14,59 A major NF-E2 binding activity was identified by gel-shift experiments and purified from mouse cells using an in vitro DNA binding assay.16-18 Partial amino acid sequence allowed the isolation of cDNA clones encoding two polypeptides, p45 and p18(MafK), which could reconstitute NF-E2 DNA binding activity as a heterodimer.

A multiplicity of cellular proteins can recognize and bind AP-1–like NF-E2 sites. This has made it difficult to prove that p45/p18(MafK) is the factor which mediates NF-E2 activity in vivo. Mutagenesis experiments have narrowed the field of candidate factors, as they have established that at least two basepairs upstream of the core AP-1 motif are important for NF-E2 activity in tissue culture cells5,7 and in transgenic mice.6,8,10 The functional NF-E2 consensus site is GCTGA(G/C)TCA (AP-1 core is underlined). This site is asymmetric, made up of a larger recognition sequence [GCTGA(C/G)] fused to a mirror image AP-1–like half site [(G/C)TCA] with an axis of dyad symmetry through the central (G/C) basepair. The Maf family of bZIP transcription factors includes all proteins shown to have a DNA binding specificity matching the larger half site. They are unique among bZIP proteins in that a highly conserved amino acid sequence adjacent to the basic domain contributes to recognition of an extended DNA binding site.60 We conclude that the functional NF-E2 binding activity consists of a Maf-like protein and a second, non-Maf protein in a heterodimer pair.

Several in vivo assays of p45/p18(MafK) function have been performed. The CB3 MEL cell line lacks p45 protein and consequently fails to activate globin gene expression upon DMSO induction.43 Re-introduction of p45 alone43 or a tethered p45/p18(MafK) heterodimer28 restores globin production. A dominant negative form of p18(MafK) blocks globin expression in wild-type MEL cells, presumably by forming nonfunctional heterodimers with all available p45.28 Each of these experiments supports a role for p45 in globin gene expression and indicates that forced expression of a p45/p18(MafK) heterodimer is sufficient to mediate NF-E2 regulatory activity.

Only targeted disruption of the murine p18(MafK) gene has directly examined the role of that protein in vivo. The p18(MafK) knockout mouse is indistinguishable from its wild-type litter mates, indicating that that protein is dispensable.45 Erythropoietic tissue from these animals has an NF-E2 DNA binding activity that comigrates with p45/p18(MafK), but this activity must contain a different Maf protein because p18(MafK) is not present.45 Taken together, these data indicate that there is functional redundancy for p18(MafK) in the mouse and raise the possibility that p18(MafK) has no physiologic role in erythropoiesis.

Following up on the original reports of NF-E2 element specificity, cited above, we believed that the protein substituting for p18(MafK) must be another member of the Maf subfamily of bZIP factors. Therefore, we sought additional Maf proteins in mammalian cells by low stringency hybridization. This report describes human MafG, which is closely related to murine p18(MafK) and which appears to be the homolog of chicken MafG. Like murine p18(MafK), human MafG is expressed ubiquitously and is present in the same cell types as p45. We show that it can dimerize with p45 to form a complex with DNA binding specificity indistinguishable from that of p45/p18(MafK).

To test whether MafG could substitute for p18(MafK) in complex with p45, we performed a tethered heterodimer experiment in CB3 cells, similar to that previously done to show the function of p45/p18(MafK) in activating globin gene expression. This experiment is informative because tethering forces the two subunits to interact exclusively with one another, producing a ‘dominant positive’ activity.49 In equivalent experiments, we found that human MafG serves just as well as murine p18(MafK) in rescuing expression of α- and β-globins. We further showed that p45/MafG can promote erythroid differentiation of CB3 cells after DMSO induction, as demonstrated by augmentation of EpoR expression. Several p45/MafG transfectants spontaneously expressed elevated levels of globins and EpoR, even without DMSO induction.

Could MafG be the Maf protein that acts at LCR NF-E2 sites in vivo? Its similarity to p18(MafK) and the similar performance of MafG and p18(MafK) in the tethered heterodimer assay suggest that these proteins may be interchangeable in the mouse, consistent with the results of the p18(MafK) knockout experiment.45 Murine MafG is present in fetal liver, and likely contributes to the NF-E2 DNA binding activity found in p18(MafK)-null animals.

The redundancy of murine small Maf proteins has made it difficult to prove their roles in erythroid gene expression in vivo. The next steps will be to produce gene-targeted mice lacking each of the small maf genes, to breed them to produce animals lacking small Mafs altogether, and to study their erythropoiesis. It seems likely that this line of experimentation will reveal other functions for Maf proteins as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Stuart Orkin and Louis Kunkel for cDNA libraries, Michael Gurish for providing the MC8 cell line, and Robert Handin for the Dami cell line. Anita Eber and Sissela Park helped in the initial phase of this project. Bernard Mathey-Prevot gave useful criticism of the manuscript.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. HL51057 to N.C.A. She is an Assistant Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. V.B. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) during the first portion of this project; he is currently a research associate of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Address reprint requests to Nancy C. Andrews, MD, PhD, Division of Hematology/Oncology Enders 720, Children's Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal