Abstract

We previously reported that monocyte adhesion to tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)–treated endothelial cells increased expression of tissue factor and CD36 on monocytes. Using immunological cross-linking to mimic receptor engagement by natural ligands, we now show that CD15 (Lewis X), a monocyte counter-receptor for endothelial selectins may participate in this response. We used cytokine production as a readout for monocyte activation and found that CD15 cross-linking induced TNF-α release from peripheral blood monocytes and cells from the monocytic cell line MM6. Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showed an increase in steady-state TNF-α mRNA after 3 to 4 hours of cross-linking. CD15 cross-linking also concomitantly increased interleukin-1β (IL-1β) mRNA, while no apparent change was observed in the levels of β-actin mRNA, indicating specificity. To examine transcriptional regulation of cytokine genes by CD15 engagement, a CAT plasmid reporter construct containing IL-1β promoter/enhancer sequences was introduced into MM6. Subsequent cross-linking of CD15 increased CAT activity. CD15 engagement by monoclonal antibody also attenuated IL-1β transcript degradation, demonstrating that signaling via CD15 also had posttranscriptional effects. Nuclear extracts of anti-CD15 cross-linked cells demonstrated enhanced levels of the transcriptional factor activator protein-1, minimally changed nuclear factor-κB, and did not affect SV40 promoter specific protein-1. We conclude that engagement of CD15 on monocytes results in monocyte activation. In addition to its well-recognized adhesive role, CD15 may function as an important signaling molecule capable of initiating proinflammatory events in monocytes that come into contact with activated endothelium.

SEVERAL STUDIES HAVE suggested a role for monocyte adhesion molecules in amplifying cellular signaling and thus enhancing monocyte activation. Engagement of CD11/CD18 integrins, for example, has been shown to enhance endotoxin-induced monocyte activation.1 We have recently reported that monocyte adhesion to cytokine-activated endothelial cells induced tissue factor (TF ) and CD36 expression on the monocyte surface and that engagement of endothelial cell E-selectin with monocyte counter-receptors, such as CD15 (Lewis X), was necessary for the response.2,3 Weyrich et al4 have shown that monocyte adhesion to P-selectin also induced cell activation as manifested by increased secretion of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), although concomitant stimulation with platelet-activating factor was required.

Recognition of endothelial selectins by leukocytes requires cell surface expression of specific fucosylated carbohydrate structures.5,6 These include Lewis X (CD15), sialylated Lewis X (sCD15), and dimeric sialylated Lewis X (dsCD15).5,7-9 CD15 and related carbohydrates are found on numerous cellular proteins involved in cellular adhesive events and have a broad cellular distribution including leukocytes10 and tumor cells.11,12 Most of the CD15-related antigens are present on either glycoproteins or glycolipids. On neutrophils, CD15 is associated with several proteins of various molecular weights in the range of 105 and 165 kD.10 Although immunopreciptation studies indicate that CD15 is present on CD11/CD18 integrins,10,13 leukocytes from patients genetically deficient in CD11/CD18 (Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency) also bear CD15.14 Using microsequence and mass spectrometry, Mahrenholz et al15 recently established that CD15 is also associated with a member of the carcinoembryonic antigen-related family of cell adhesion molecules. The exact identity of the proteins and lipid moieties bearing the CD15 antigen that are involved in leukocyte adhesion and signaling is not known.10 Recently putative glycoprotein ligands for P-selectin (designated PSGL-1) and E-selectin (designated ESL-1) have been identified on human and mouse leukocytes, respectively.16

Immunological and cDNA transfection studies strongly suggest that these may be the major leukocyte counter-receptors for P- and E-selectin, and that recognition requires expression of the glycoprotein ligand and the fucosylated carbohydrate (generated by expression of a specific fucosyl transferase).17

Several studies have suggested that CD15 containing structures may mediate cell activation in neutrophils.18,19 Anti-CD15 antibodies inhibited the oxidative burst in neutrophils induced by zymosan particles and inhibited phagocytosis of IgG- and C-opsonized particles and bacteria.18 Furthermore, antibodies to CD15 have been shown to induce a transient increase in CD11/CD18 binding activity in neutrophils.19 In a recent study, we showed that anti-CD15 antibodies inhibited neutrophil recruitment in vivo and prevented the neutrophil-dependent pulmonary vascular injury.20

In contrast to these reported studies of the function of CD15 expressed by neutrophils, the role of CD15 has not been elucidated on mononuclear phagocytes. Monocyte adhesion to cytokine-activated endothelial cells is presumed to be an important early event in the development of proinflammatory lesions and atherosclerosis. We have recently shown that binding of monocytes to activated endothelium induced a phenotypic change in the adherent monocytes resulting in an increase in the surface expression of tissue factor procoagulant and CD36 (a receptor for thrombospondin and oxidized light density lipoprotein).2 3 Engagement of E-selectin with its counter-receptor(s) was a critical part of this phenotypic transformation. We thus hypothesize that engagement of CD15 may, at least in part, mediate monocyte activation. To test this hypothesis, we have used an immunological cross-linking approach to mimic the engagement of CD15 during monocyte attachment to activated endothelium. We found that cross-linking of CD15 resulted in the rapid activation of monocytes as evidenced by translocation of transcriptional factors such as activator protein-1 (AP-1), increased cytokine generation, and upregulation of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) gene promoter activity. These data suggest that engagement of CD15 by its natural ligands may result in the activation of a variety of macrophage responses and thus contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammation and vascular disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.RPMI-1640 and M199 were obtained from BioWhitaker (Walkersville, MD). Hanks' balanced salt solution, Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), trypsin-EDTA, L-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from GIBCO (Grand Island, NY). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from GIBCO containing <1 ng/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS (Escherichia Coli, J5) was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). All reagents were checked for the presence of endotoxin by a sensitive Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (BioWhittaker), and found to have <20 pg/mL. Human platelet-poor plasma was prepared from healthy donors. Phosphoinositol specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). All other chemicals were of reagent grade.

Monocytic cells.Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from freshly drawn blood by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation.21 Typically, cell viability exceeded 98% as assessed by Trypan blue exclusion. In some experiments, monocytes were depleted from peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes by adhesion to plastic tissue cultured dishes (Falcon, Frankin Lakes, NJ) for 60 minutes at 37°C. This process was repeated three times, and nonadherent lymphocytes were then harvested by washing with RPMI 1640 medium. For studies requiring large numbers of cells (eg, mRNA levels, mRNA degradation, and electromobility gel shift studies), we used a human monocyte-like cell line, Mono Mac 6 (MM6) provided by Dr H.W.L. Ziegler-Heitbrock (Institut fur Immunologie, Universitat Munchen).22 Pilot studies were performed to verify that these cells behaved similarly to freshly isolated monocytes in terms of cytokine and tissue factor production in response to CD15 cross-linking. These cells have been extensively characterized and shown to exhibit morphological, biochemical, and physiological features of mature monocytes,22 including the expression of CD14 and CD15 as assessed by flow cytometry (data not shown).

Antibodies.Purified murine anti-CD15 IgM monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) 80H5 and UN-172 were obtained from the Fifth Workshop and Conference on Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens 23and PM81 from Medarex (West Lebanon, NH). Murine IgM VIM2 against CD65 (dimeric sialyl-CD15) was a generous gift of Dr W. Knapp (Kaumberg, Austria). Hybridomas of additional control IgM MoAb 1B2 (against Type II lactosamine chains) and CSLEX1 (against sialyl-CD15) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). Ascities of these MoAbs were prepared in mice using a standard protocol and IgM subsequently purified by gel-filtration chromatography (Windsor Park Lab Inc, Teaneck, NJ). IgG anti-monocyte control antibodies, Hec 7 (CD31), IB4 (CD11/18), and W6/32 (HLA Class I) were from Dr W. Muller (Rockefeller University, New York, NY), Dr S. Wright (Rockefeller University), and ATCC, respectively. Anti-CD15 (PM81) and anti-CD31 (hec 7) antibodies were fluorescein conjugated by incubating 500 μL of MoAb (1 mg/mL at pH 9.0) with 50 μL fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (1 mg/mL) in the dark for 8 hours at 4°C. Unbound FITC was removed by extensive dialysis. Affinity purified F(ab)′2 goat antimouse IgM or IgG were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, NJ). All MoAbs were used at saturating concentrations (≈10 μg/mL) at a level that resulted in minimal cell aggregation as assessed by flow cytometry and light microscopy.

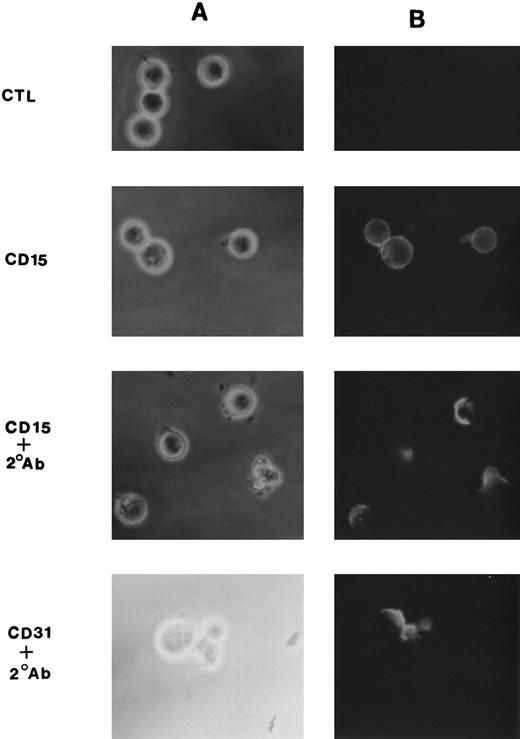

Cross-linking studies.Monocytic cells (5 × 105) were suspended in culture medium containing 10 μg of anti-CD15 MoAb per mL and incubated at 4°C for 20 minutes. Cells were then washed and incubated with F(ab)′2 fragments of goat antimouse IgM or IgG (10 μg/mL) at 4°C for 20 minutes. To allow cross-linking, cells were washed and then warmed to 37°C before performing assays described below.24 To assess for optimal cross-linking, in some studies FITC-conjugated antibodies were used and cells were examined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy 10 minutes after rewarming. As shown in Fig 1, in the absence of the F(ab)′2 secondary antibody, anti-CD15 (PM81, IgM) stained monocytic cells (MM6) in a rim pattern consistent with a uniform surface distribution of antigen. In the presence of the cross-linking F(ab)′2 , however, the fluoresence pattern changed with clear demonstration of antigen patching and capping of antigen of a majority of cells (≈70%). Similar results were seen with multiple control IgM and IgG antimouse monocytic antibodies. A fluorescence micrograph of CD31 is shown in Fig 1 as a representative example.

Cross-linking induced patching and capping of CD15. MM6 cells (1 × 106) were suspended in culture medium containing 10 μg FITC-conjugated anti-CD15 or anti-CD31 MoAb per mL and incubated at 4°C for 20 minutes. Cells were then washed and incubated with F(ab) ′2 fragments of goat anti-mouse IgM (for CD15) or IgG (for CD31) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL at 4°C for 20 minutes. Cells were washed and then warmed to 37°C for 10 minutes and examined by fluorescent microscopy. Shown are phase-fluoresecence pairs (A and B, respectively) for cells incubated with anti-CD15 alone (second row), anti-CD15 plus F(ab) ′2 secondary antibody (third row), and anti-CD31 plus F(ab) ′2 secondary antibody (bottom). The top row shows cells incubated with the F(ab) ′2 secondary antibody in the absence of primary antibody.

Cross-linking induced patching and capping of CD15. MM6 cells (1 × 106) were suspended in culture medium containing 10 μg FITC-conjugated anti-CD15 or anti-CD31 MoAb per mL and incubated at 4°C for 20 minutes. Cells were then washed and incubated with F(ab) ′2 fragments of goat anti-mouse IgM (for CD15) or IgG (for CD31) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL at 4°C for 20 minutes. Cells were washed and then warmed to 37°C for 10 minutes and examined by fluorescent microscopy. Shown are phase-fluoresecence pairs (A and B, respectively) for cells incubated with anti-CD15 alone (second row), anti-CD15 plus F(ab) ′2 secondary antibody (third row), and anti-CD31 plus F(ab) ′2 secondary antibody (bottom). The top row shows cells incubated with the F(ab) ′2 secondary antibody in the absence of primary antibody.

Enzymatic removal of monocyte surface CD14.Mononuclear cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) were suspended for 60 minutes at 37°C in HEPES-buffered RPMI 1640 containing bovine serum albumin (BSA) (2 mg/mL) and PI-PLC (10 U/mL, equivalent to ≈15 μg/mL). After the treatment, cells were washed twice with RPMI and then cross-linked with CD15 MoAb as described above. Loss of CD14 surface expression was monitored by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS), and was consistently ≥70% (data not shown).

Cytokine assays.An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Clontech Lab, Inc, Palo Alto, CA) was used to monitor the release of TNF-α from monocytes after cross-linking CD15.25 Quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to measure steady-state levels of TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA.26 Total RNA was isolated from MM6 cells (2 × 106 cells) with RNAzol (Biotecx Lab, Inc, Houston, TX), reversed transcribed,26 and a known amount of cDNA (0.2 μg/2 μL) amplified in the presence of defined concentrations of a synthetic competitor DNA for 30 cycles using specific primer pairs (Clontech). Control reactions included RNA samples in which the reverse transcription reaction mixture was omitted. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels, visualized by ethidium bromide staining, and photographed. The negatives of the photographs were analyzed by laser densitometry, and the absolute absorbance values of the PCR products were determined. The ratios of the absorbance of the relevant PCR product pairs were plotted against the concentration of the competitor DNA and the concentration of PCR product calculated.

Preparation of nuclear extracts.Nuclear extracts of monocytic cells (MM6) were harvested using the modified protocol of Schrieber et al27 following cell stimulation with either CD15 cross-linking or bacterial LPS (10 ng/mL) for timed intervals from 15 to 180 minutes at 37°C. Protein concentrations of the nuclear extracts were determined using the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and stored at −70°C until use.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.Double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the immunoglobulin κ light chain NF-κB consensus sequence (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′), the AP-1 consensus sequence (5′-CGCTTGATGAGTCAGCCGGAA-3′), and the SV40 promoter specific protein-1 (SP-1) consensus sequence (5′-ATTCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAGC-3′) were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed as described by Delude et al.25 In some experiments, 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled oligonucleotides were preincubated with the protein on ice for 5 minutes before the addition of the radioactive probe to assess the specificity of protein/DNA complexes. Competition for binding to the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) oligonucleotide was seen with 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled NF-κB oligonucleotide, but not with excesses of the AP-1 or SP-1 oligonucleotides (data not shown), thus demonstrating that only NF-κB was actually present in the nuclear fraction obtained from unstimulated MM6.

IL-1β promotor regulation.An IL-1β promoter/enhancer construct consisting of −3757 bp to +15 bp of the human IL-1β gene coupled to the thymidine kinase promoter and the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene28 was transfected into MM6 using a modified DEAE-Dextran method. After 48 hours, the cells were exposed to LPS (1 μg/mL) or cross-linked with anti-CD15 for 16 hours at 37°C. Unstimulated cells served as negative controls. Following stimulation, transfected cells were then harvested and disrupted by three freeze-thaw cycles. Supernatants were mixed with 14C-chloramphenicol (DuPont NEN, Boston, MA) and acetyl-CoA (Sigma) for 6 hours. Acetylated 14C-chloramphenicol species were separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) in chloroform:methanol (vol/vol, 95:5). The dried TLC sheet was exposed to KODAK X-OMAT AR film (VWR Scientific, Piscataway, NJ) and quantified by PhosphoImager. Transfection efficiency was normalized by cotransfection with a β-galactosidase expression plasmid.

IL-1β mRNA stability.To determine if CD15 cross-linking affected IL-1β mRNA degradation, we examined IL-1β mRNA stability in monocytic cells (MM6) treated with actinomycin D (5 μg/mL), which blocks the initiation of mRNA transcription. Total RNA was harvested from actinomycin D-treated MM6 at different times (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours) following cell stimulation. Quantitative RT-PCR was then performed on this RNA.

Statistical analysis.All values were expressed as means ± standard error (SE). Student's t-test was used to compare means for statistical significance at P < .05.

RESULTS

Immunologic Cross-Linking CD15 on Monocytes Induced TNF-α Release

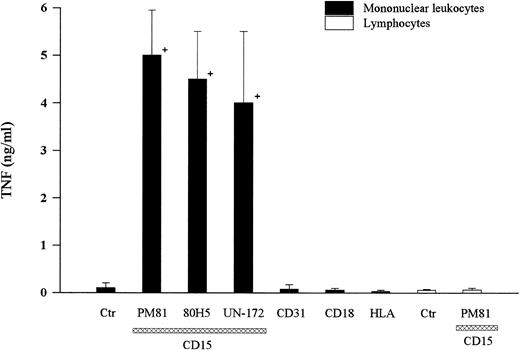

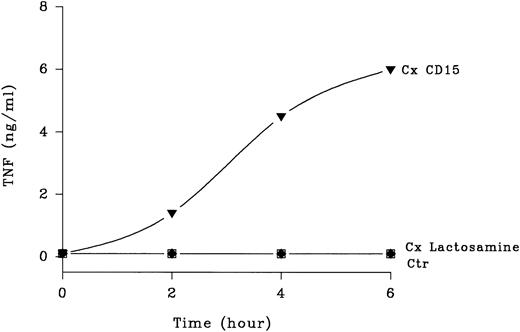

Cross-linking CD15 on human mononuclear leukocytes with any of three MoAbs (ie, PM81, 80H5, UN-172) induced significant TNF-α release (Fig 2). Time course studies showed that TNF-α release was detected by 2 to 3 hours and reached a peak at 6 hours (Fig 3). At 6 hours, 5 to 10 ng of TNF-α was present per mL of conditioned media harvested from anti-CD15 cross-linked monocytes, compared with <0.5 ng/mL from the untreated cells, thus representing >10-fold increase from the basal levels. Cross-linking other cell surface antigens expressed abundantly on monocytes, including the glycoproteins CD31, CD11/CD18, and HLA with IgG MoAbs did not induce TNF-α release. Furthermore, cross-linking structurally related carbohydrate antigens with specific IgM MoAbs, including nonsialylated lactosamine, sialyl-CD15, and dimeric sialyl-CD15 also had no effect (Fig 3), demonstrating specificity. We and others have established that lymphocytes do not express CD156 and treatment of mononuclear fractions that had been depleted of monocytes (ie, >95% CD2+ lymphocytes as determined by flow cytometry) by the same three anti-CD15 antibodies did not induce detectable TNF-α release (<0.1 ng/mL, n = 3 experiments), demonstrating that monocytes were the likely source of the TNF-α released from the mononuclear cell preparations.

Cross-linking CD15 induced TNF-α release. Human peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes prepared by ficoll gradient centrifugation (2 × 106 cells) were incubated with three anti-CD15 IgM MoAbs (PM81, 80H5, UN-172) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then cross-linked by the addition of goat anti-IgM F(ab) ′2 and allowed to incubate for 6 hours at 37°C. TNF-α released into the culture supernatant was then determined by ELISA. A representative of six separate experiments is shown. Cross-linking mononuclear leukocytes with anti-CD31 (MoAb hec-7), anti-CD11/CD18 (MoAb IB4), or anti-HLA (MoAb W6/32) for 6 hours was used for comparison. To determine the cell source of TNF-α, monocyte-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (<95% lymphocytes) were shown not to screte TNF, either under basal conditions (labeled control) or after CD15 cross-linked for 6 hours at 37°C (last column). + = Significantly different from control (P < .05).

Cross-linking CD15 induced TNF-α release. Human peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes prepared by ficoll gradient centrifugation (2 × 106 cells) were incubated with three anti-CD15 IgM MoAbs (PM81, 80H5, UN-172) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then cross-linked by the addition of goat anti-IgM F(ab) ′2 and allowed to incubate for 6 hours at 37°C. TNF-α released into the culture supernatant was then determined by ELISA. A representative of six separate experiments is shown. Cross-linking mononuclear leukocytes with anti-CD31 (MoAb hec-7), anti-CD11/CD18 (MoAb IB4), or anti-HLA (MoAb W6/32) for 6 hours was used for comparison. To determine the cell source of TNF-α, monocyte-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (<95% lymphocytes) were shown not to screte TNF, either under basal conditions (labeled control) or after CD15 cross-linked for 6 hours at 37°C (last column). + = Significantly different from control (P < .05).

Kinetics of CD15-mediated TNF-α release. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (2 × 106) were purified as in Fig 1 and incubated with primary anti-CD15 IgM PM81 (10 μg/mL), anti-lactosamine IgM IB2 (10 μg/mL) or no MoAb. Following addition of a cross-linking secondary F(ab) ′2 goat anti-mouse IgM, culture supernatants were harvested at various timed points from 2 to 6 hours. TNF-α levels in the supernatant were then determined by ELISA after centrifugation to remove cellular debris. One of three representative experiments with similar results is shown. Each point represents mean TNF-α released. Standard deviations (not shown) were 10% or less of the means.

Kinetics of CD15-mediated TNF-α release. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (2 × 106) were purified as in Fig 1 and incubated with primary anti-CD15 IgM PM81 (10 μg/mL), anti-lactosamine IgM IB2 (10 μg/mL) or no MoAb. Following addition of a cross-linking secondary F(ab) ′2 goat anti-mouse IgM, culture supernatants were harvested at various timed points from 2 to 6 hours. TNF-α levels in the supernatant were then determined by ELISA after centrifugation to remove cellular debris. One of three representative experiments with similar results is shown. Each point represents mean TNF-α released. Standard deviations (not shown) were 10% or less of the means.

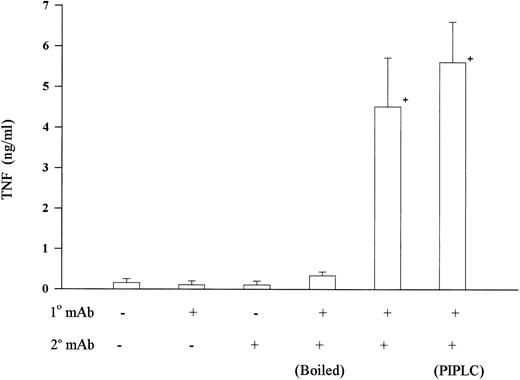

Bacterial LPS is a potent inducer of TNF-α release from monocytes and commonly contaminates many reagents. LPS concentrations in all MoAb preparations were <0.06 ng/mL as determined by a limulus lysate assay. We also performed a series of studies showing that the effect of cross-linking CD15 was likely not the result of undetectable LPS contamination. Neither primary nor secondary antibody alone was sufficient to induce TNF-α release (Fig 4). LPS is heat stable, yet boiling the primary MoAb completely abolished antibody-induced TNF-α release (Fig 4). Furthermore, LPS activation has been shown to require monocyte expression of CD14, a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-linked protein. The nearly complete removal of CD14 by treatment with PIPLC-specific phospholipase C (15 μg/mL) did not abrogate the TNF-α release induced by CD15 cross-linking (Fig 4), while it completely abolished TNF-α release induced by LPS (data not shown). These data indicate that monocyte activation mediated by CD15 could not be attributed to LPS contamination and suggest a distinct signaling pathway.

LPS was not involved in CD15-mediated TNF-α release. Human peripheral mononuclear cells were isolated and CD15 was cross-linked as in Fig 1. Incubation of either primary MoAb PM81 alone or secondary antibody alone did not increase TNF-α release. Also, boiling the primary MoAb (100°C for 15 minutes) abrogated the TNF-α-inducing effect. Incubating mononuclear cells with phosphoinositol specific phospholipase C (PIPLC, 15 μg/mL) for 60 minutes at 37°C, to remove the LPS receptor (ie, CD14) before cross-linking with CD15 MoAb had no effect. + = Significantly different from control (P < .05).

LPS was not involved in CD15-mediated TNF-α release. Human peripheral mononuclear cells were isolated and CD15 was cross-linked as in Fig 1. Incubation of either primary MoAb PM81 alone or secondary antibody alone did not increase TNF-α release. Also, boiling the primary MoAb (100°C for 15 minutes) abrogated the TNF-α-inducing effect. Incubating mononuclear cells with phosphoinositol specific phospholipase C (PIPLC, 15 μg/mL) for 60 minutes at 37°C, to remove the LPS receptor (ie, CD14) before cross-linking with CD15 MoAb had no effect. + = Significantly different from control (P < .05).

Molecular Basis of Cytokine Release Induced by Cross-Linking CD15

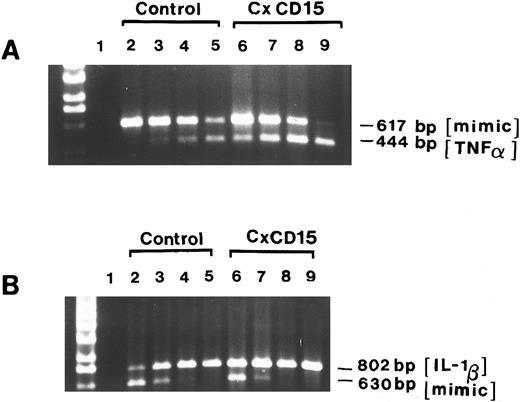

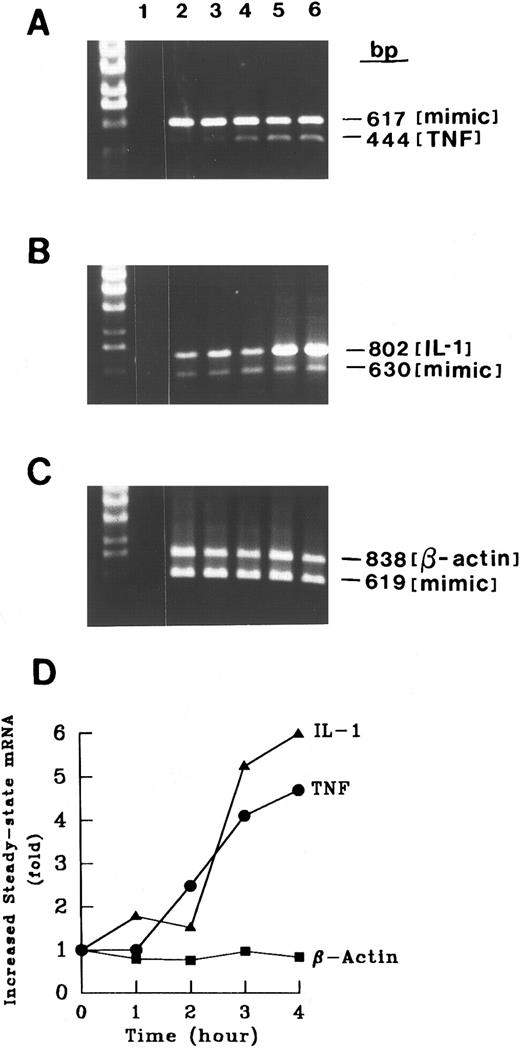

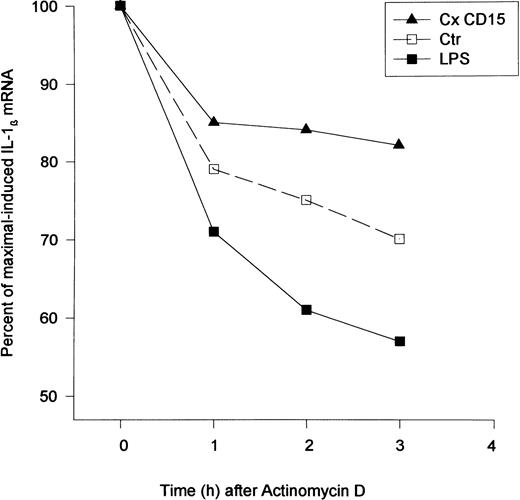

Induction of cytokine mRNA.Cross-linking CD15 on monocytic cells (MM6) induced an increase in steady-state mRNA levels of TNF-α and IL-1β at 4 hours as compared with basal levels (Fig 5). We detected a time-dependent increase in both TNF-α and IL-1β mRNAs (Fig 6). A control transcript, β-actin, did not change (Fig 6). To determine if CD15 may alter mRNA degradation, we treated MM6 cells with actinomycin D (5 μg/mL), which inhibits transcription. While LPS (10 ng/mL) enhanced the degradation of IL-1β transcripts, CD15 cross-linking resulted in a reduction in the rate of IL-1β mRNA degradation (Fig 7). To assess the mechanism by which CD15 may mediate the changes in cytokine mRNAs, we also studied expression of an IL-1β promoter/enhancer plasmid construct transfected into MM6 cells. We found that cross-linking CD15 on MM6 cells transiently transfected with a region of the IL-1β promoter spanning −3757 bp to +15 bp coupled to CAT induced an ≈ fourfold to sevenfold increase in CAT activity over that of untreated cells (n = 5 experiments). These data suggest that cytokine release induced by cross-linking CD15 was the result of both a specific increase in gene transcription, and in the case of IL-1β, a reduction in the rate of mRNA degradation.

Steady-state cytokine mRNA levels increased after CD15 cross-linking. Two micrograms of total RNA from unstimulated MM6 cells (as a control) or MM6 that were stimulated with anti-CD15 cross-linking (PM81, 10 μg/mL, 4 hours) were used as templates for cDNA synthesis. Aliquots were then amplified in the presence of 10-fold serial dilutions of the TNF-α competitors (617 bp) or IL-1β competitors (802 bp) (lanes 2 to 9). Lane 1 depicts control PCR whereby the reverse transcription reaction mixture was omitted. Lanes 2 to 5 represent the coamplification of cDNA from unstimulated MM6 cells and serial dilutions of the competitor DNA at 10−17, 10−18, 10−19, 10−20mol/L for TNF-α (A) and IL-1β (B), respectively. Lanes 6 to 9 represent the coamplification of cDNA from CD15-cross-linked (4 hours) and competitor serial dilutions of 10−17, 10−18, 10−19, 10−20 mol/L for TNF-α (A) and IL-1β (B), respectively. Aliquots of the final PCR products were resolved on a 1.6% EtBr-agarose gel.

Steady-state cytokine mRNA levels increased after CD15 cross-linking. Two micrograms of total RNA from unstimulated MM6 cells (as a control) or MM6 that were stimulated with anti-CD15 cross-linking (PM81, 10 μg/mL, 4 hours) were used as templates for cDNA synthesis. Aliquots were then amplified in the presence of 10-fold serial dilutions of the TNF-α competitors (617 bp) or IL-1β competitors (802 bp) (lanes 2 to 9). Lane 1 depicts control PCR whereby the reverse transcription reaction mixture was omitted. Lanes 2 to 5 represent the coamplification of cDNA from unstimulated MM6 cells and serial dilutions of the competitor DNA at 10−17, 10−18, 10−19, 10−20mol/L for TNF-α (A) and IL-1β (B), respectively. Lanes 6 to 9 represent the coamplification of cDNA from CD15-cross-linked (4 hours) and competitor serial dilutions of 10−17, 10−18, 10−19, 10−20 mol/L for TNF-α (A) and IL-1β (B), respectively. Aliquots of the final PCR products were resolved on a 1.6% EtBr-agarose gel.

Time course of CD15-induced increase in cytokine mRNA levels. RNA from control MM6 cells (1 × 106 cells) or MM6 cells cross-linked for various times (1 to 4 hours) was analyzed as in Fig 4. For each experiment, control tubes in which reverse transcriptase or RNA was excluded gave no signal after amplification, documenting the absence of contamination. The competitor concentrations used were 10−20 mol/L for TNF-α, 10−20mol/L for IL-1β, and 10−20mol/L β-actin. Thirty cycles of PCR were performed and the PCR amplified products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. β-Actin served as a negative control. Increased steady-state mRNAs were calculated using zero time as a reference. Shown is a representative experiment of four separate experiments with similar results.

Time course of CD15-induced increase in cytokine mRNA levels. RNA from control MM6 cells (1 × 106 cells) or MM6 cells cross-linked for various times (1 to 4 hours) was analyzed as in Fig 4. For each experiment, control tubes in which reverse transcriptase or RNA was excluded gave no signal after amplification, documenting the absence of contamination. The competitor concentrations used were 10−20 mol/L for TNF-α, 10−20mol/L for IL-1β, and 10−20mol/L β-actin. Thirty cycles of PCR were performed and the PCR amplified products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. β-Actin served as a negative control. Increased steady-state mRNAs were calculated using zero time as a reference. Shown is a representative experiment of four separate experiments with similar results.

Effect of CD15 cross-linking on IL-1β mRNA stability. CD15 cross-linking reduced IL-1β degradation. Mono Mac 6 cells (2 × 106/condition) were incubated with an anti-CD15 MoAb (PM81, 10 μg/mL) for 20 minutes followed by F(ab) ′2 goat antimouse IgM (10 μg/mL). Actinomycin D (5 μg/mL) was added to cells 2 hours after the CD15 cross-linking and total RNA was extracted at the designated time (hours). The level of steady-state of IL-1β mRNA was estimated by quantitative RT-PCR. The percent of maximal-induced IL-1β was calculated using the 2-hour time point as the zero time reference for comparison with the residual IL-1β mRNA at the later time points. Shown is a representative experiment of two separate studies.

Effect of CD15 cross-linking on IL-1β mRNA stability. CD15 cross-linking reduced IL-1β degradation. Mono Mac 6 cells (2 × 106/condition) were incubated with an anti-CD15 MoAb (PM81, 10 μg/mL) for 20 minutes followed by F(ab) ′2 goat antimouse IgM (10 μg/mL). Actinomycin D (5 μg/mL) was added to cells 2 hours after the CD15 cross-linking and total RNA was extracted at the designated time (hours). The level of steady-state of IL-1β mRNA was estimated by quantitative RT-PCR. The percent of maximal-induced IL-1β was calculated using the 2-hour time point as the zero time reference for comparison with the residual IL-1β mRNA at the later time points. Shown is a representative experiment of two separate studies.

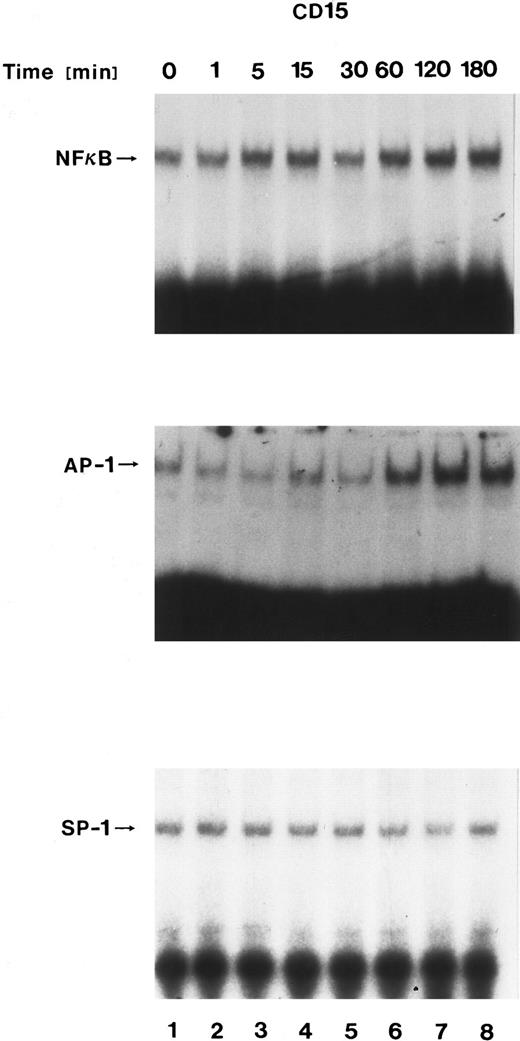

Nuclear translocation of transcription factors after CD15 cross-linking.To identify potential transcriptional factors involved in mediating CD15-induced gene regulation, we assessed nuclear fractions of stimulated monocytes using an electrophoretic mobility gel shift assay. Nuclear extracts obtained from untreated MM6 cells contained minor constitutive levels of proteins that bound synthetic DNA oligomers representing binding sites for AP-1, NF-κB, or SP-1. The specificity of complex formation was demonstrated by competition experiments with unlabeled oligonucleotides. Cross-linking CD15 induced increased binding of nuclear proteins to the labeled AP-1 oligomer, but only minimal changes of the NF-κB and no changes of SP-1 levels (Fig 8). In contrast, cross-linking nonfucosylated lactosamine carbohydrate antigens (MoAb IB2) had no effect, demonstrating specificity.

Nuclear translocation of transcription factors after CD15 cross-linking. Nuclear extracts from Mono Mac 6 cells cross-linked with an anti-15 MoAb (PM81, 10 μg/mL) for varying time periods were incubated with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide binding sites for AP-1, NF-κB, or SP-1. Binding of specific nuclear proteins was detected by a shift in electrophoretic mobility. Cross-linking CD15 increased AP-1, while only minimally effecting NF-κB and SP-1.

Nuclear translocation of transcription factors after CD15 cross-linking. Nuclear extracts from Mono Mac 6 cells cross-linked with an anti-15 MoAb (PM81, 10 μg/mL) for varying time periods were incubated with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide binding sites for AP-1, NF-κB, or SP-1. Binding of specific nuclear proteins was detected by a shift in electrophoretic mobility. Cross-linking CD15 increased AP-1, while only minimally effecting NF-κB and SP-1.

DISCUSSION

Data from our laboratory and others2-4 suggest that E-selectin tethering of monocytes on cytokine-activated endothelial cells may contribute to monocyte activation during the early stages of the inflammatory response. In this study we report that immunologic cross-linking of an E-selectin ligand, CD15, induced expression of proinflammatory cytokines through activation of transcriptional and posttranscriptional pathways. The effect of CD15 cross-linking was specific, as cross-linking of other surface antigens with isotypic MoAbs to other carbohydrate and glycoprotein antigens had no effect. Furthermore, our experimental result cannot be accounted for by LPS contamination because boiling of anti-CD15 MoAb abolished TNF induction, while enzymatic removal of the LPS receptor, CD14, had no effect.

While the sialylated form of CD15 is probably the major recognition motif for E-selectin–mediated leukocyte attachment to activated endothelial cells,29,30 the role of nonsialylated CD15 in monocyte adhesion is less clear. Our data, however, clearly demonstrate that cross-linking CD15, but not sCD15 or dimeric sCD15, resulted in monocyte activation. It is conceivable that E-selectin interaction with sialyl-CD15 may predominately mediate initial monocyte tethering, while concomitant or subsequent engagement of the nonsialylated form then mediates cell activation. The capacity of CD15 to activate monocytes may be particularly relevant to atherosclerosis where monocyte adhesion is an early and prominent histological feature. Consistent with this hypothesis is the finding by Landers et al31 that a subpopulation of adherent macrophages associated with the intimal lumen during early lesions of atherosclerosis expressed high levels of tissue factor.

The exact nature of the putative protein molecule(s) bearing CD15 that mediates cell-activation is unknown.6 Albrechtsen et al10 have shown that CD15 is associated with CD11/CD18 integrins, but CD15 is also found on neutrophils from leukocyte-deficient patients (lacking CD11/CD18),12 and blockade of CD11/CD18 did not effect monocyte activation by adhesion to TNF-treated endothelial cells.2 Enzymatic removal of CD14 did not affect the cellular response, indicating a minimal role, if any, for this LPS receptor in mediating the CD15 effect. Engagement of a number of monocyte antigens, including CD44 and CD45, has been shown to cause monocyte activation and lead to TNF-α release in vitro,32 whether the CD44 and CD45 glycoproteins bear CD15 is unknown. It is also not known whether a human homologue of the recently identified murine ESL-1 glycoprotein is present on monocytes, or whether ESL-1 is capable of transmitting cellular signals.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays demonstrated that CD15 cross-linking was associated with specific nuclear signaling events. Cross-linking CD15 led to a time-dependent increase in nuclear translocation of AP-1 and a small increase in NF-κB, but not SP-1. The AP-1 increase is consistent with the experimental data from many laboratories showing that AP-1 may be critical in monocyte activation including cytokine-dependent TNF-α, tissue factor, and IL-1β induction.33 Sequence analysis of TNF-α, tissue factor and IL-1β promoters indicate the presence of multiple sites for AP-1, NF-κB, and SP-1.34,35 It is of interest to note that LPS-dependent activation differed from CD15 cross-linking in that LPS increases both NF-κB and AP-1, while CD15 was mainly dependent on AP-1, suggesting that the signals associated with CD15 ligation are unique. In parallel with our data are those of Haskill et al36 who have shown that monocyte adhesion to substratum increased the mRNA of the protein components of AP-1, c-jun, and c-fos. While the exact cellular signaling pathway mediated by the CD15 in monocytes awaits further investigations, our data suggest that CD15-mediated monocyte activation may represent a novel and distinct signaling pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We express our thanks to Dr John Ho for his help in the study; Agathi Vallianatos, Lisa Bovis, and Susan Liu for their excellent technical assistance; and Zheng Qinghu for graphical illustrations.

Supported by Grant-In-Aid from the American Heart Association to S.K.L., National Institutes of Health Grants No. HL49883 to S.K.L., GM47127 to D.T.G., AI33087 to D.T.G., AR42588 to R.L.S., and HL46403 to R.L.S. D.T.G. is a recipient of a Junior Faculty Award from the American Cancer Society and S.K.L. is a fellow of the Dorothy Rodbell Cohen Foundation for Sarcoma Research.

Address reprint requests to Siu K. Lo, PhD, Department of Medicine (Hematology & Oncology), Cornell University Medical College, 1300 York Ave, New York, NY 10021.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal