Abstract

Type I interferons (IFNs-α and IFN-β) bind to a common receptor to exert strong antiproliferative activity on a broad range of cell types, including interleukin-6 (IL-6)–dependent myeloma cells. In this study, we investigated the effect of IFN-β pretreatment on IL-6–stimulated mitogenic signaling in the human myeloma cell line U266. IL-6 induced transient tyrosine phosphorylation of the IL-6 receptor signal-transducing subunit gp130, the gp130-associated protein tyrosine kinases Jak1, Jak2, and Tyk2, the phosphotyrosine phosphatase PTP1D/Syp, the adaptor protein Shc and the mitogen-activated protein kinase Erk2, and accumulation of GTP-bound p21ras. Prior treatment of U266 cells with IFN-β downregulated IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of gp130, Jak2, PTP1D/Syp, Shc, and Erk2, and GTP-loading of p21ras. Further analysis indicated that treatment with IFN-β disrupted IL-6–induced binding of PTP1D/Syp to gp130 and the adaptor protein Grb2; IFN-β pretreatment also interfered with IL-6–induced interaction of Shc with Grb2 and a 145-kD tyrosine-phosphorylated protein. These results suggest a novel mechanism whereby type I IFNs interrupt IL-6–promoted mitogenesis of myeloma cells in part by preventing the formation of essential signaling complexes leading to p21ras activation.

INTERLEUKIN-6 (IL-6) is a pleiotropic cytokine produced by a variety of cell types.1 The various activities of IL-6 are the result of its interaction with a membrane receptor consisting of an 80-kD ligand-binding α subunit (gp80), which triggers association with a 130-kD β subunit (gp130), a common signaling component shared with other members of the IL-6 cytokine superfamily.2-4 Ligation of the IL-6 receptor induces homodimerization and tyrosine phosphorylation of gp130, and activation of associated members of the Janus (Jak) family of protein tyrosine kinases.5-9 The spectrum of Jak kinases activated is variable and reportedly cell-type specific.6,7 Formation of this signaling complex subsequently leads to the activation of two members (Stat1α and Stat3) of the STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) family of latent cytoplasmic transcription factors,5,7,10-12 as specified by modular tyrosine-based motifs present in gp130.13 Besides the Jak/STAT pathway, the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogenactivated protein (MAP) kinase pathway has also been implicated as a signaling cascade mediating the various IL-6–induced cellular responses.4 14-19

One of the many biological activities of IL-6 is as a growth factor for murine plasmacytoma/hybridomas and human myeloma cells.20-24 Proteins potentially involved in transmission of a proliferative signal in these cells include components of the Jak/STAT pathway,6,7,19 as well as other nonreceptor tyrosine kinases25 and as yet unidentified tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins.7,26 However, activation by IL-6 of Raf-1, MEK1 (MAP kinase kinase) and Erk2 in myeloma cells implicates the ERK pathway,18,19 and two lines of indirect evidence suggest that the mitogenic signal proceeds through p21ras. First, IL-6 has been shown to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of the p52 isoform of Shc (p52shc), its association with the adaptor molecule Grb2 and recruitment of the p52shc-Grb2 complex to gp130 in myeloma cells,19 the p52shc-Grb2 complex functioning in other systems to activate p21ras to the guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP) form via the guanine nucleotide exchange factor SOS.15,27 Second, expression of oncogenic p21ras in IL-6–dependent myeloma cells was reported to lead to significant IL-6–independent growth.28 Nonetheless, it has not yet been demonstrated that p21ras is activated in the context of IL-6–stimulated myeloma cell proliferation,14,29 the potential contribution of Ras-independent ERK cascades in transducing a mitogenic signal from IL-6 not being excluded.30-32

Type I interferons (IFNs-α/β) are members of a heterogeneous family of cytokines that activate some of the same signaling intermediaries as IL-6. This is best documented in the case of the Jak/STAT pathway.33-35 The recent demonstration that IFN-β activates Erk2 and its association with Stat1α has shown further similarities between the signaling cascades triggered by IL-6 and IFNs-α/β, while providing a link between the ERK and Jak/STAT pathways.36 Despite the sharing of signaling components, type I IFNs, which bind competitively to a common receptor,37-39 often induce the opposite biologic effect in myeloma cells to that elicited by IL-6 (ie, growth arrest).40-42 The mechanism through which IFNs-α/β establish an antiproliferative state is largely unknown. Treatment with IFNs-α/β results in the induction of a set of genes, including 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase and the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase, which may play a role in this process.43 Transcription factors such as the STATs and IRF-1 are involved in regulating the expression of type I IFN-inducible genes.35,44 45

It was previously reported that pretreatment of monocytes with IFNγ-γ blocked colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1)–induced proliferation.46 While CSF-1 receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and interaction with proximal signaling molecules such as Grb2 were not affected, CSF-1–stimulated activation of Erk1/Erk2 was interrupted by IFNγ-γ treatment, with protein kinase C (PKC)-δ being identified as a primary target for the IFN-γ–mediated inhibitory effects. In this study, we employed the human myeloma cell line U266 to likewise investigate the mechanism of IFN-β–induced inhibition of IL-6–dependent cell growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.Recombinant human IL-6 (specific activity, 9.1 × 107 U/mg) was a gift from Sandoz Pharmaceuticals Corp (East Hanover, NJ) and IFN-β (specific activity, 2.0 × 108 U/mg) was purchased from Life Technologies, Inc (Gaithersburg, MD). The antiphosphotyrosine (anti-pTyr) monoclonal antibody (MoAb), 4G10, as well as rabbit polyclonal antibodies to gp130, Jak1, Jak2, Tyk2, and Shc were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc (Lake Placid, NY). The anti-pan–Erk and anti-PTP1D/Syp MoAbs were from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY) and the anti-Grb2 MoAb from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc (West Grove, PA). Enhanced chemiluminescence reagents for Western blotting were purchased from Amersham Canada Ltd (Oakville, Ontario) and Immobilon-P was from Millipore Corp (Bedford, MA).

Cell culture.The human myeloma cell line U266, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD), was maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with 50 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies, Inc). For serum deprivation experiments, cells were grown in IMDM supplemented with 0.5% FCS.

Ras assay.The analysis of p21ras-bound GTP/GDP was determined essentially as described previously.47 Cells were collected, washed twice with phosphate-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) and resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/mL in the same medium containing 0.5% dialyzed FCS. After 12 hours, 0.2 mCi/mL of carrier-free 32Pi (Amersham) was added and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 hours. When included, IFN-β (500 U/mL) was added 3 hours after the addition of 32Pi and 50 minutes before addition of IL-6. Cells were more than 95% viable after deprivation as judged by staining with trypan blue (0.04%). After activation with IL-6 (25 ng/mL) as indicated, cells were collected and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4 ), and lysed in 50 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 1% Triton X-100, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L MgCl2 , 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 0.1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mmol/L GTP and 0.1 mmol/L guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP). Nuclei were removed by centrifugation and Ras protein was immunoprecipitated by the addition of 10 μg of rat anti-Ras MoAb (Y13-259) for 1 hour at 4°C followed by the addition of protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech Inc, Piscataway, NJ) for an additional 1 hour. Precipitates were washed eight times with 50 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 500 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L MgCl2 , 1% Triton X-100, and 0.005% SDS, and p21ras-bound nucleotides eluted by incubation at 65°C in 25 μL of 2 mmol/L EDTA, 2 mmol/L dithiothreitol and 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Nucleotides were separated by thin layer chromatography on polyethyleneimine cellulose F plates (EM Separations, Gibstown, NJ) in 0.75 mol/L KH2PO4 (pH 3.5). Plates were imaged and radioactivity quantitated using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and the GTP/GTP+(1.5) GDP ratios calculated.

Western blotting and immunoprecipitations.U266 cells were treated as above with the exception that IMDM supplemented with 0.5% FCS was used during the starvation period. Subsequent to IL-6 induction, the cells were collected by centrifugation and washed once with ice-cold PBS containing 1 mmol/L Na3VO4 . Cell lysates were prepared using a buffer containing 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 137 mmol/L NaCl, 100 mmol/L NaF, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4 , 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/mL aprotinin and 10 μg/mL leupeptin. Lysates were incubated on ice for 15 minutes and particulate material removed by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 14,000g.

For analysis of global patterns of protein tyrosine phosphorylation,7 an equivalent volume of 2 × SDS sample buffer (120 mmol/L Tris [pH 6.8], 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 100 mmol/L dithiothreitol) was added to the lysate, the samples were placed in a boiling water bath for 2 minutes, separated in SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon-P using 25 mmol/L Tris, 192 mmol/L glycine, and 20% methanol. For immunoprecipitations, the lysate was precleared with protein A-sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech Inc) for 1 hour followed by incubation with polyclonal antibodies for 1 to 2 hours at 4°C, before collection of immune complexes with protein A-sepharose for an additional 1 hour. The protein A-sepharose beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, bound proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS-sample buffer, separated in SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon-P as described above. Membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and 6% bovine serum albumin for at least 1 hour, incubated with primary antibody for 1 hour, washed for 30 minutes with TBS-T, and developed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated second antibody for 45 minutes. Blots were washed again for 30 minutes with TBS-T, incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate solution and exposed to Kodak X-Omat film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Immunoblots of immunoprecipitated Jak kinases were initially probed with 4G10, stripped by rinsing twice with 62.5 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 100 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol for 20 minutes at 50°C, washed with TBS-T, and reprobed with either Jak1, Jak2, or Tyk2 as indicated. In the case of the Jak kinases, sequential immunoprecipitations were performed on individual lysates. In these instances, lysates were cleared twice with protein-A sepharose beads between successive immunoprecipitations to ensure that there was no carry over between experiments. This was routinely confirmed by immunoblot analysis.

In vitro binding studies.The glutathione S-transferase (GST) expression constructs containing the Grb2 cDNA (GST-Grb2) or the Grb2 SH2 domain (GST-Grb2SH2) have been previously described.48 GST-fusion proteins expressed in bacteria were prepared by purification onto glutathione sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia Biotech Inc, Piscataway, NJ) and used for binding assays as described.49 50 For each reaction, lysates were precleared with glutathione sepharose 4B beads before incubation with GST-fusion proteins (5 to 10 μg) bound to these beads for 1 to 4 hours at 4°C. After incubation, the beads were collected and washed three times with lysis buffer. Protein complexes were then eluted in SDS-sample buffer and analyzed by Western blotting as described above.

Cell proliferation assay.U266 cells were incubated at an initial concentration of 3 × 105/mL (200 μL/well) with or without the addition of IFN-β (200 U/mL) for various times. DNA was labeled by adding 0.2 μCi [3H]thymidine per well for 18 hours starting at the indicated times. Incorporation of radioactivity into precipitable material was measured using a Skatron cell harvester (Skatron Inc, Sterling, VA) and quantified in a Wallac model 1205 Beta plate reader (Wallac-Pharmacia, Baie D'Urfe, Canada).

RESULTS

IFN-β inhibits [3H] thymidine incorporation in U266 cells.Previous studies have shown that growth of U266 cells is regulated by IL-6 through an autocrine mechanism and that IFN-α exerts a dominant antiproliferative effect on IL-6–supported U266 growth.42 51 The results shown in Fig 1 demonstrate that IFN-β (200 U/mL) also has a similar inhibitory effect on U266 growth. This inhibition of U266 proliferation prompted us to examine the effects of IFN-β on IL-6–induced signal transduction.

IFN-β inhibits proliferation of U266 cells. U266 cells (3 × 105/mL) were incubated in medium containing 10% FCS for various times with (♦) or without (▪) IFN-β (200 U/mL). At the times indicated, [3H]thymidine (0.2 μCi/200 μL) was added for 18 hours and incorporated radioactivity measured as described in Materials and Methods.

IFN-β inhibits proliferation of U266 cells. U266 cells (3 × 105/mL) were incubated in medium containing 10% FCS for various times with (♦) or without (▪) IFN-β (200 U/mL). At the times indicated, [3H]thymidine (0.2 μCi/200 μL) was added for 18 hours and incorporated radioactivity measured as described in Materials and Methods.

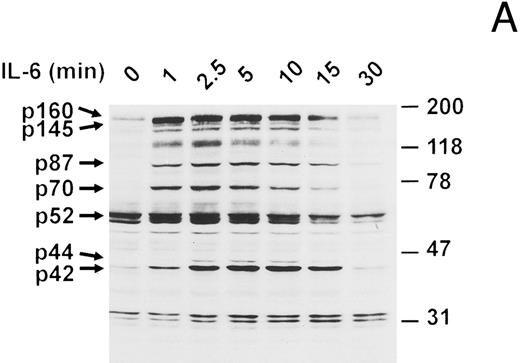

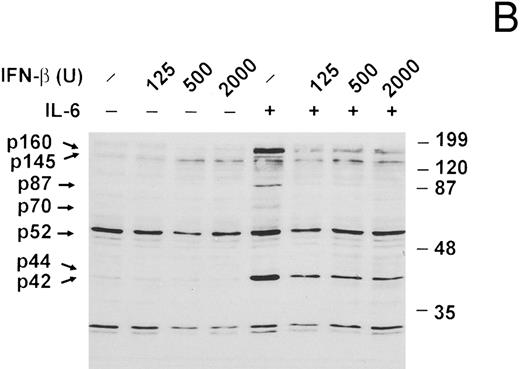

IFN-β blocks IL-6-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation.To determine if interruption of IL-6 signaling may account for the growth inhibitory effects of IFN-β, we investigated the changes in IL-6 signaling subsequent to IFN-β pretreatment. Analysis of serum-starved U266 myeloma cells stimulated with IL-6 showed the rapid induction of several tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins, the most prominent of which have apparent molecular masses of 160, 145, 87, 70, 52, 44 (weakly phosphorylated), and 42 kD (Fig 2A). These tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins are similar in size to a subset of those induced in ANBL-6 myeloma cells,7 suggesting their potential involvement in transmission of a mitogenic signal from IL-6. The induction kinetics varied somewhat among these proteins: p160, p70, and p52 demonstrated peak phosphorylation by 2.5 minutes, which declined thereafter, while p87, p44, and p42 showed a progressive increase in phosphorylation for at least 5 minutes. In all cases, the levels of phosphorylation declined to basal states by 30 minutes. The 70-, 52-, 44-, and 42-kD proteins have mobilities similar to PTP1D/Syp, p52shc, Erk1 (p44mapk) and Erk2 (p42mapk), respectively.19,30,49,52 53 The identity of these proteins was confirmed by further studies (see below).

IL-6–induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation in U266 cells and effect of IFN-β pretreatment. (A) Serum-deprived (14 hours) U266 cells were exposed to IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for the indicated times. Whole-cell extracts equivalent to 8 × 105 cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-pTyr MoAb (1:1,000 dilution) to detect tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. Representative of five separate experiments. (B) Serum-deprived U266 cells were treated with various doses of IFN-β (U/mL) for 50 minutes before addition of IL-6 (25 ng/mL) where indicated and subjected to immunoblotting with an anti-pTyr MoAb as in (A). Representative of three separate experiments. (C) U266 cells pretreated with or without IFN-β (500 U/mL) for 50 minutes were induced with IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for 10 minutes. Lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with a MoAb to pTyr (4G10) followed by stripping and reprobing with a MoAb recognizing Erks. Representative of three separate experiments. Proteins discussed in the text are indicated by arrows. The sizes of molecular mass markers (Prestained SDS-PAGE standards, broad range, and low range; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA) are indicated in thousands of daltons.

IL-6–induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation in U266 cells and effect of IFN-β pretreatment. (A) Serum-deprived (14 hours) U266 cells were exposed to IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for the indicated times. Whole-cell extracts equivalent to 8 × 105 cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-pTyr MoAb (1:1,000 dilution) to detect tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. Representative of five separate experiments. (B) Serum-deprived U266 cells were treated with various doses of IFN-β (U/mL) for 50 minutes before addition of IL-6 (25 ng/mL) where indicated and subjected to immunoblotting with an anti-pTyr MoAb as in (A). Representative of three separate experiments. (C) U266 cells pretreated with or without IFN-β (500 U/mL) for 50 minutes were induced with IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for 10 minutes. Lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with a MoAb to pTyr (4G10) followed by stripping and reprobing with a MoAb recognizing Erks. Representative of three separate experiments. Proteins discussed in the text are indicated by arrows. The sizes of molecular mass markers (Prestained SDS-PAGE standards, broad range, and low range; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA) are indicated in thousands of daltons.

Serum-starved U266 cells were next treated with various doses of recombinant IFN-β 50 minutes before stimulation with IL-6 for 10 minutes (Fig 2B). IFN-β pretreatment was found to significantly inhibit the IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of p160, p145, p87, p70, and p42. In general, the lowest IFN-β dose employed (125 U/mL) was sufficient to accomplish maximal inhibition. The identity of p42 as Erk2 was confirmed in a similar experiment (Fig 2C). IL-6 induced both tyrosine phosphorylation and a shift in the mobility of Erk2 (denoted pErk2), which were inhibited by IFN-β pretreatment (500 U/mL).

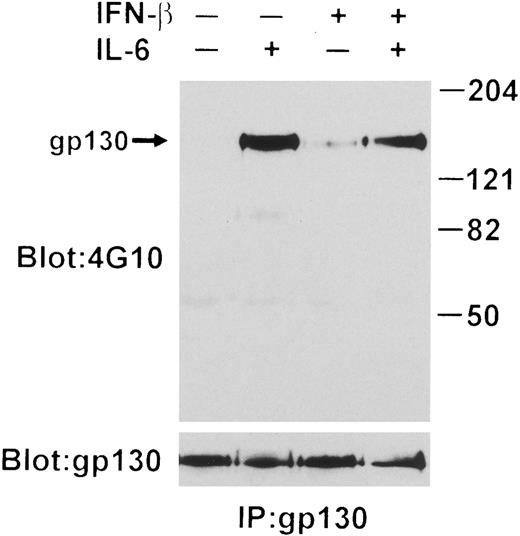

IFN-β influences IL-6-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of gp130.Tyrosine phosphorylation of gp130 is essential for transduction of signals triggered by IL-6.54 Because tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins migrating with molecular masses similar to gp130 (145 to 160 kD) was repressed by IFN-β, we examined the modification of gp130 directly by phosphotyrosine immunoblotting following immunoprecipitation of this protein. As shown in Fig 3, this analysis revealed a partially reduced level of IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of gp130 after IFN-β treatment. Interestingly, IFN-β treatment in the absence of IL-6 stimulated a slight increase in the level of gp130 tyrosine phosphorylation. The level of gp130 protein detected was not altered by IFN-β pretreatment.

IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of gp130 interrupted by IFN-β. gp130 was immunoprecipitated from lysates prepared from 1 × 107 U266 cells treated with IFN-β (500 U/mL) for 50 minutes or without followed by induction with or without IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for 10 minutes. Immunoblotting was performed with both anti-pTyr MoAb and anti-gp130. Arrow indicates the position of gp130.

IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of gp130 interrupted by IFN-β. gp130 was immunoprecipitated from lysates prepared from 1 × 107 U266 cells treated with IFN-β (500 U/mL) for 50 minutes or without followed by induction with or without IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for 10 minutes. Immunoblotting was performed with both anti-pTyr MoAb and anti-gp130. Arrow indicates the position of gp130.

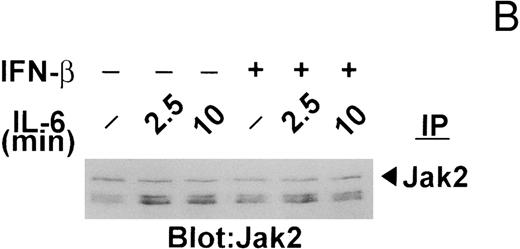

Changes in the tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak kinases following IFN-β pretreatment.Previously, we7 and others6,19 showed that the protein tyrosine kinases Jak1, Jak2, and/or Tyk2 are transiently phosphorylated on tyrosine in murine and human myeloma cell lines after exposure to IL-6. Because IFNs-α/β signal through Jak1 and Tyk2,35 we were interested in next examining whether the changes in the IL-6–induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation observed with IFN-β pretreatment were accompanied by altered phosphorylation of Jak kinases. As shown in Fig 4A, all three Jak kinases were rapidly (within 2.5 minutes) phosphorylated following IL-6 stimulation of serum-starved U266 cells, Jak2, and Tyk2 being strongly phosphorylated and Jak1 less so. As expected, IFN-β selectively induced the phosphorylation of Jak1 and Tyk2, but had no effect on Jak2. Exposure of U266 cells to IL-6 following IFN-β pretreatment resulted in further elevation in the levels of phosphorylation of Jak1 and Tyk2. On the other hand, IFN-β pretreatment repressed to some degree the IL-6–induced phosphorylation of Jak2, raising the possibility that IFN-β might interfere with IL-6 signaling in U266 cells in part by attenuating Jak2 activation (see Discussion). Concomitant with the decrease in Jak2 phosphorylation was increased tyrosine phosphorylation of two coprecipitating proteins of higher apparent molecular mass. Reprobing of this blot with polyclonal antibodies against Jak2 showed no change in Jak2 protein levels following IFN-β treatment (Fig 4B).

IFN-β pretreatment attenuates IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak2. (A) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from serum-deprived (14 hours) U266 cells pretreated with IFN-β (500 U/mL) for 50 minutes and then exposed to IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for the times indicated. Jak2, Jak1, and Tyk2 were sequentially immunoprecipitated from the same extracts and subjected to immunoblotting with an anti-pTyr MoAb. (B) The blot shown for Jak2 in (A) was stripped and reprobed with the immunoprecipitating MoAb to Jak2 to demonstrate equal loading and that the higher molecular mass bands detected with the anti-pTyr MoAb were not cross-reacting proteins recognized by the anti-Jak2 MoAb. The Jak/Tyk-specific bands are denoted by arrows. Representative of three separate experiments.

IFN-β pretreatment attenuates IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak2. (A) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from serum-deprived (14 hours) U266 cells pretreated with IFN-β (500 U/mL) for 50 minutes and then exposed to IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for the times indicated. Jak2, Jak1, and Tyk2 were sequentially immunoprecipitated from the same extracts and subjected to immunoblotting with an anti-pTyr MoAb. (B) The blot shown for Jak2 in (A) was stripped and reprobed with the immunoprecipitating MoAb to Jak2 to demonstrate equal loading and that the higher molecular mass bands detected with the anti-pTyr MoAb were not cross-reacting proteins recognized by the anti-Jak2 MoAb. The Jak/Tyk-specific bands are denoted by arrows. Representative of three separate experiments.

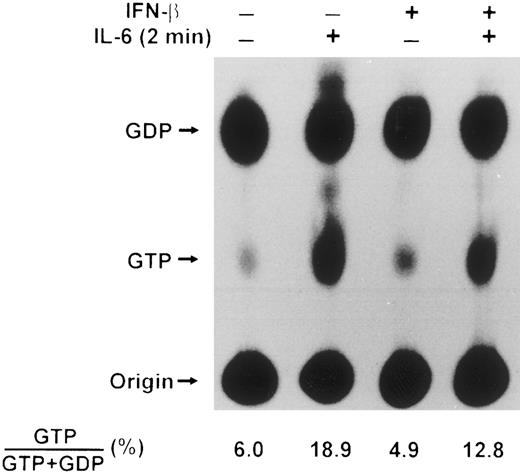

IFN-β pretreatment influences the activation of p21ras by IL-6.Because p21ras involvement in IL-6–induced activation of Erk2 in the AF10 subclone of U266 cells had been inferred,18,19 we next decided to examine directly the ability of IL-6 to induce GTP loading of p21ras in our U266 cell line and to assess whether IFN-β affected this process. Although p21ras has been implicated in IL-6–mediated signaling in other systems,4,29 there has been only one previous report documenting an increase in GTP-bound p21ras in IL-6–stimulated cells. This involved the rat PC12 pheochromocytoma cell line, which can be induced to differentiate into neuron-like cells by IL-655; in the PC12 system, p21ras activation was apparent only if the cells were pretreated with sodium orthovanadate, a potent inhibitor of phosphotyrosine phosphatases, but which possesses other pharmacological activities.14 Accordingly, we determined the activation state of p21ras in serum-starved U266 cells treated with IL-6 by labeling with 32Pi , in the absence of sodium orthovanadate, and immunoprecipitating Ras proteins. As demonstrated in Fig 5, IL-6 increased the percentage of GTP bound to p21ras approximately threefold. The increase in accumulation of GTP bound to p21ras following exposure to IL-6 was rapid with 19% of nucleotide bound by 2 minutes and decreasing shortly thereafter (data not shown). When IFN-β was added before IL-6 treatment of U266 cells, a partial inhibition of IL-6–stimulated p21ras activation was observed, with the maximum percentage of GTP bound to p21ras detected at 2 minutes reaching only 13%. These data thus established that p21ras is a downstream component of an IL-6 signaling pathway associated with cellular proliferation.56 Moreover, the decreased GTP-loading of p21ras observed after IFN-β treatment suggested that at least one target of IFN-β-induced inhibition of IL-6–stimulated Erk2 phosphorylation was upstream of p21ras.

Effect of IL-6 and IFN-β on p21ras activation in U266 cells. U266 cells were deprived of serum for 14 hours, labeled with 32Pi (0.2 mCi/mL) for the last 4 hours of serum deprivation and incubated for 50 minutes with or without IFN-β (500 U/mL) followed by IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for 2 minutes as indicated. Whole cell extracts from 1 × 107 cells were prepared, Ras proteins immunoprecipitated with Y13-259 MoAb, and nucleotides bound analyzed by thin layer chromatography on polyethyleneimine cellulose F plates in 0.75 mol/L KH2PO4 . The positions of GDP and GTP are indicated. Results presented are representative of three separate experiments, with the mean values shown below.

Effect of IL-6 and IFN-β on p21ras activation in U266 cells. U266 cells were deprived of serum for 14 hours, labeled with 32Pi (0.2 mCi/mL) for the last 4 hours of serum deprivation and incubated for 50 minutes with or without IFN-β (500 U/mL) followed by IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for 2 minutes as indicated. Whole cell extracts from 1 × 107 cells were prepared, Ras proteins immunoprecipitated with Y13-259 MoAb, and nucleotides bound analyzed by thin layer chromatography on polyethyleneimine cellulose F plates in 0.75 mol/L KH2PO4 . The positions of GDP and GTP are indicated. Results presented are representative of three separate experiments, with the mean values shown below.

IFN-β pretreatment interrupts IL-6-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PTP1D/Syp and association with Grb-2.Several routes of p21ras activation have been described in various cell types following stimulation with growth factors and cytokines. Recently, the phosphotyrosine phosphatase PTP1D/Syp (also called SHPTP2 and PTP2C) was found to couple Grb2 to the PDGFR leading to p21ras activation.52,53,57-59 As noted above, the approximately 70-kD protein phosphorylated on tyrosine in response to IL-6 and inhibited by IFN-β pretreatment is similar in molecular mass to PTP1D/Syp. Previously, Boulton et al17 reported an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of PTP1D/Syp following treatment of EW-1 (Ewing's sarcoma) cells with the IL-6–type cytokine ciliary neurotrophic factor, and Stahl et al13 identified the tyrosine-based motif in gp130, which is required for binding of PTP1D/Syp. To determine the status of PTP1D/Syp phosphorylation in this system, U266 cells, with or without IFN-β pretreatment, were exposed to IL-6 and the degree of tyrosine phosphorylation of PTP1D/Syp was evaluated following immunoprecipitation with a PTP1D/Syp-specific MoAb. As shown in Fig 6, IL-6 induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PTP1D/Syp and this was almost completely abrogated by IFN-β pretreatment. Stripping and reprobing of the blot with a PTP1D/Syp-specific MoAb demonstrated equivalent amounts of PTP1D/Syp immunoprecipitated. Because tyrosine phosphorylation of PTP1D occurs following recruitment to gp130, the reduced gp130 and PTP1D/Syp phosphorylation observed following IFN-β treatment predicts a corresponding decrease in gp130-PTP1D interaction. This prediction was confirmed by immunoprecipitation of lysates from control and IFN-β–treated cells with gp130 followed by probing with a PTP1D/Syp specific MoAb. As shown in the lower panel of Fig 6, IL-6 induced an association between these proteins, which was significantly impaired by IFN-β pretreatment.

IFN-β downregulates IL-6–induced PTP1D/Syp tyrosine phosphorylation and association with gp130. PTP1D/Syp was immunoprecipitated from lysates of IFN-β and IL-6–treated U266 cells (1 × 107) followed by immunoblotting with both anti-pTyr (top panel) and anti-PTP1D/Syp (middle panel) specific MoAbs. The lower panel shows samples (1.5 × 107 cells) immunoprecipitated with gp130 followed by probing with anti-PTP1D/Syp specific MoAb. Arrow indicates the position of PTP1D/Syp.

IFN-β downregulates IL-6–induced PTP1D/Syp tyrosine phosphorylation and association with gp130. PTP1D/Syp was immunoprecipitated from lysates of IFN-β and IL-6–treated U266 cells (1 × 107) followed by immunoblotting with both anti-pTyr (top panel) and anti-PTP1D/Syp (middle panel) specific MoAbs. The lower panel shows samples (1.5 × 107 cells) immunoprecipitated with gp130 followed by probing with anti-PTP1D/Syp specific MoAb. Arrow indicates the position of PTP1D/Syp.

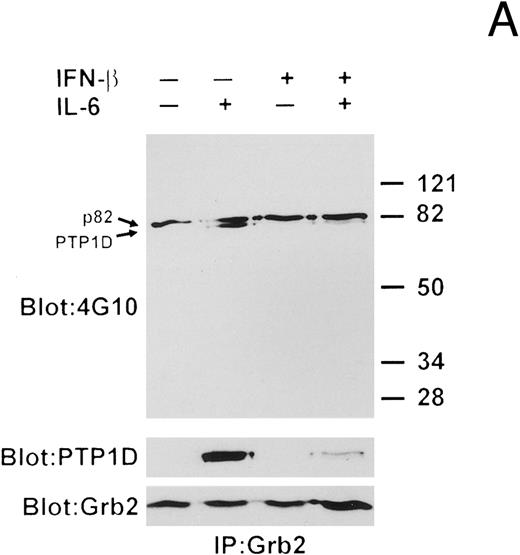

We next examined the interaction of Grb2 with PTP1D/Syp by performing Grb2 immunoprecipitations and Western blotting with anti-pTyr, anti-PTP1D/Syp, and anti-Grb2 MoAbs (Fig 7A). A constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of 82 kD (p82) coprecipitated with Grb2 under all conditions. IL-6 stimulation induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of a protein in the anti-Grb2 immunoprecipitates, which was identified as PTP1D/Syp. Pretreatment with IFN-β before IL-6 exposure was found to significantly reduce the amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated PTP1D/Syp that coprecipitated with Grb2.

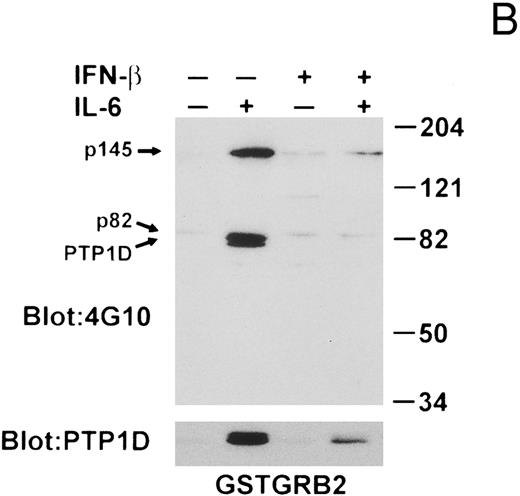

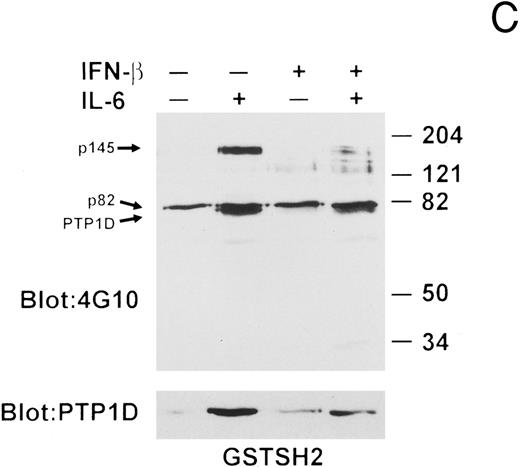

IFN-β influences the interaction of PTP1D/Syp and other tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins with GST-Grb2 fusion proteins. (A) Grb-2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates prepared from U266 cells (8 × 106) treated with IL-6 and/or IFN-β as indicated. Associated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-pTyr and anti-PTP1D/Syp specific MoAbs. Equivalent loading of Grb2 was confirmed by final reprobing of this blot with a Grb2-specific MoAb (bottom panel). (B) Extracts from U266 cells (1 × 107) treated with IFN-β and IL-6 as indicated were incubated with a GST-Grb2 fusion protein (approximately 10 μg) bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads for 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, associated proteins eluted in SDS-sample buffer, and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-pTyr and anti-PTP1D/Syp MoAbs. (C) The experiment in (B) was repeated using a GST-Grb2SH2 fusion protein (GSTSH2). (D) The experiment in (B) was repeated using control GST protein. Arrows indicate the position of PTP1D/Syp and other tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins discussed in the text.

IFN-β influences the interaction of PTP1D/Syp and other tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins with GST-Grb2 fusion proteins. (A) Grb-2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates prepared from U266 cells (8 × 106) treated with IL-6 and/or IFN-β as indicated. Associated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-pTyr and anti-PTP1D/Syp specific MoAbs. Equivalent loading of Grb2 was confirmed by final reprobing of this blot with a Grb2-specific MoAb (bottom panel). (B) Extracts from U266 cells (1 × 107) treated with IFN-β and IL-6 as indicated were incubated with a GST-Grb2 fusion protein (approximately 10 μg) bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads for 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, associated proteins eluted in SDS-sample buffer, and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-pTyr and anti-PTP1D/Syp MoAbs. (C) The experiment in (B) was repeated using a GST-Grb2SH2 fusion protein (GSTSH2). (D) The experiment in (B) was repeated using control GST protein. Arrows indicate the position of PTP1D/Syp and other tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins discussed in the text.

To obtain data supporting the notion that IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PTP1D/Syp enables formation of PTP1D/Syp-Grb2 complexes in this system and that IFN-β pretreatment negatively influenced this association, we next performed in vitro bead-binding assays using GST-fusion proteins. In the first set of experiments, a GST-fusion protein containing the entire Grb2 protein was used, followed by Western blotting with anti-PTyr and anti-PTP1D/Syp MoAbs (Fig 7B). The GST-Grb2 fusion protein bound an 82-kD tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in untreated lysates, which remained stably associated in lysates of IFN-β and/or IL-6–stimulated cells. Treatment of the cells with IL-6 led to a substantial increase in the association of tyrosine-phosphorylated PTP1D/Syp and a prominently tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of 145 kD (p145). IFN-β alone stimulated the association of a number of proteins, but abrogated the IL-6–induced binding of PTP1D/Syp, as well as p145 to Grb2.

To further investigate the nature of the interaction between PTP1D/Syp and Grb2, we repeated the in vitro bead-binding assays using a GST-fusion protein containing the Grb2 Src homology 2 (SH2) domain. As can be seen in Fig 7C, the results were essentially identical to those obtained with the full-length Grb2 protein, establishing that the PTP1D/Syp-Grb2 complex formed upon IL-6 stimulation, and disrupted by IFN-β pretreatment, occurs through binding of the Grb2 SH2 domain to tyrosine-phosphorylated PTP1D/Syp. These data also indicate that a similar mechanism is operative for the IL-6–stimulated and IFN-β-inhibited interaction of Grb2 with p145. Finally, the data argue that the constitutive association of tyrosine-phosphorylated p85 is likewise mediated by the Grb2 SH2 domain and that the additional proteins that bind to the full-length GST-Grb2 fusion in lysates of IL-6- and/or IFN-β–treated U266 cells must interact with other regions of Grb2, as no proteins bound to GST alone (Fig 7D).

Tyrosine phosphorylation and interaction of proteins with Shc is regulated by both IL-6 and IFN-β.A second adaptor protein, p52shc, which functions upstream of p21ras by binding to the Grb2-SOS complex15,48 has also been reported to associate with Grb2 after IL-6 stimulation.19 We confirmed and extended these findings by probing the blots shown in Fig 7 with Shc-specific antibodies (Fig 8). We were able to detect only the 52-kD isoform of Shc bound to the Grb2 GST-fusion proteins and found that IL-6 stimulated enhanced association of this protein with both full-length Grb2, as well as the SH2 domain of Grb2. IFN-β treatment itself resulted in increased association of p52shc with Grb2 at the 50-minute time point, although the enhanced binding of p52shc to Grb2 seen following IL-6 treatment was significantly hindered. We could not detect any binding of p46shc to the Grb2 GST-fusion proteins even though this isoform was readily detected in whole cell lysates (see Fig 9). These results were corroborated by Western blot analysis of anti-Shc immunoprecipitates with anti-Grb2 MoAbs (Fig 8).

IFN-β and IL-6 influence the interaction of Shc proteins with Grb2. Extracts prepared from IL-6 and IFN-β stimulated U266 cells were used for either GST-fusion protein interaction studies (top three panels) or immunoprecipitation with anti-Shc antibodies (bottom panel). In all cases lysates were incubated with the specified fusion proteins or antibodies for 2 hours at 4°C and associated proteins detected by immunoblotting with either anti-Shc (in the case of Grb2 fusion protein interaction studies) or anti-Grb2 MoAbs (in the case of Shc immunoprecipitations).

IFN-β and IL-6 influence the interaction of Shc proteins with Grb2. Extracts prepared from IL-6 and IFN-β stimulated U266 cells were used for either GST-fusion protein interaction studies (top three panels) or immunoprecipitation with anti-Shc antibodies (bottom panel). In all cases lysates were incubated with the specified fusion proteins or antibodies for 2 hours at 4°C and associated proteins detected by immunoblotting with either anti-Shc (in the case of Grb2 fusion protein interaction studies) or anti-Grb2 MoAbs (in the case of Shc immunoprecipitations).

Effect of IL-6 and IFN-β on the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc isoforms and Shc-associated proteins in U266 cells. Serum-deprived U266 cells were pretreated with IFN-β (500 U/mL) for 50 minutes and then exposed to IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for the times indicated. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from 1 × 107 cells, immunoprecipitated with an anti-Shc MoAb and subjected to immunoblotting with an anti-pTyr MoAb. The p52shc and p46shc isoforms, and the p145 and p45 Shc-associated proteins discussed in the text are indicated by arrows. Representative of four separate experiments.

Effect of IL-6 and IFN-β on the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc isoforms and Shc-associated proteins in U266 cells. Serum-deprived U266 cells were pretreated with IFN-β (500 U/mL) for 50 minutes and then exposed to IL-6 (25 ng/mL) for the times indicated. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from 1 × 107 cells, immunoprecipitated with an anti-Shc MoAb and subjected to immunoblotting with an anti-pTyr MoAb. The p52shc and p46shc isoforms, and the p145 and p45 Shc-associated proteins discussed in the text are indicated by arrows. Representative of four separate experiments.

In addition to Grb2, Shc has also recently been shown to interact with tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins of approximately 145 kD (p145) in certain hematopoietic cell lines stimulated with IL-3, Steel factor, and erythropoietin,60,61 as well as in fibroblasts stimulated with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF ) or fibroblast growth factor.62 We had noted that a protein(s) migrating with an apparent molecular mass of 145 to 160 kD is tyrosine phosphorylated following IL-6 treatment of U266 cells (Fig 2A) and shows sensitivity to IFN-β pretreatment (Fig 2B). An IFN-sensitive tyrosine-phosphorylated protein(s) in this size range was also found to associate with Grb2 in response to IL-6 (Fig 7B and C). To determine whether Shc might be associated with a 145-kD tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in IL-6–stimulated U266 cells and whether IFN-β pretreatment might affect the tyrosine phosphorylation state of Shc and/or this interaction, cells with or without IFN-β pretreatment were incubated with IL-6 for various times, lysed, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Shc antibodies followed by immunoblotting with the anti-pTyr MoAb. As can be seen in Fig 9, the p52shc and p46shc isoforms of Shc were tyrosine phosphorylated at a basal level. Upon stimulation with IL-6, the levels of phosphorylation of both p52shc and p46shc increased and a 145-kD tyrosine-phosphorylated protein was present in the immunoprecipitates. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the 145-kD Shc-binding protein was maximal at 2.5 minutes. At this time point, the p66shc isoform49 could also be visualized upon longer exposure of the blot. Treatment of the cells with IFN-β for 50 minutes in the absence of IL-6 also produced an increase in the level of phosphorylation of p52shc and p46shc. The increased tyrosine phosphorylation of p52shc is consistent with the finding of enhanced association of this protein with Grb2 (mediated via the Grb2 SH2 domain) at the 50-minute time point following IFN-β treatment (Fig 8). Interestingly, a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of 45 kD (p45) was also found in the anti-Shc immunoprecipitates following IFN-β treatment. When cells that had been pretreated with IFN-β were subsequently exposed to IL-6, both p145 and p45 coprecipitated with p52shc and p46shc. Whereas the levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of both Shc isoforms and p45 were slightly increased 2.5 minutes after exposure to IL-6, the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of p145 (or the amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated p145 bound to Shc) was reduced compared with that observed in response to IL-6 alone.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have identified components of the canonical Ras pathway as targets for growth inhibitory molecules. For example, elevated cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate levels have been reported to block growth factor-induced mitogenic signaling by interfering with ERK activation at the level of Raf-1.63 More recently, it was shown that IFN-γ blocked CSF-1–stimulated proliferation of monocytes46 also by delivering an antiproliferative signal to the ERK pathway. In this case, PKC-δ was identified as a potential target for inhibition at a point upstream of Raf-1. In U266 myeloma cells, we have demonstrated partial downregulation of IL-6–induced Erk2 and p21ras activation with the IFN-β pretreatment regimen employed. Using PKC inhibitors (staurosporin and calphostin C), we were unable to demonstrate a significant role of PKC in IL-6 signal transduction (data not shown).26 In addition, pretreatment of U266 cells with IFN-β had no effect on the ability of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate to activate Erk2 in these cells (data not shown). Taken together, these results imply that PKC-δ is probably not a target for IFN-β blockage of IL-6–stimulated U266 proliferation; the ERK/MAP kinase pathway activated by IL-6 in U266 cells thus differs qualitatively from that induced by CSF-1.

To identify the receptor proximal components responsible for the IFN-β–induced decrease in activation of p21ras and Erk2, we investigated the effects of IFN-β on other IL-6 signaling molecules. The most upstream signaling component affected by IFN-β pretreatment was gp130, in which a partial downregulation of IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation was detected. This finding, which most likely accounts for the subsequent disruption of downstream signaling events, distinguishes the present study from the IFN-γ induced effects on CSF-1 signaling,46 where no changes in receptor tyrosine phosphorylation were observed. The gp130-associated Jak kinases are responsible for tyrosine phosphorylation of gp130 and other essential signaling components such as STATs and PTP1D/Syp.5,6,8,64,65 Three members of this family, Jak1, Jak2 and Tyk2, are activated upon exposure of U266 cells to IL-6. IFN-β was found to negatively influence the IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak2 and promote its association with ancillary proteins. It is tempting to speculate that this modulation of Jak2 activation may account for the reduced phosphorylation of gp130 because successive treatment with INF-β and IL-6 had an additive effect on Jak1 and Tyk2 tyrosine phosphorylation. However, reduced availability of the IFN-β used kinases; Jak1 and Tyk2, could also contribute to the level of IL-6–induced gp130 tyrosine phosphorylation. This scenario implies functional nonequivalency among the Jak/Tyk kinases, a characteristic recently described in human fibrosarcoma cells activated with IL-664 and IFN-β.66 Overexpression of dominant-negative mutants of Jak kinases in U266 cells will be necessary to define the role of each kinase in these cells.64,66 67

Abrogation of gp130 tyrosine phosphorylation would be predicted to block activation of SH2-containing signaling components, which function by directly interacting with the sites involved. Stahl et al13 identified the gp130 tyrosine motifs essential for interaction with a number of SH2-containing signaling molecules including STATs and PTP1D/Syp. The gp130 tyrosine motif proximal to the membrane (QYSTV) is responsible for IL-6–induced association with the amino-terminal SH2 domain of PTP1D/Syp and for subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation of PTP1D/Syp to occur. Recent studies have defined PTP1D/Syp as an adaptor molecule leading to the downstream activation of p21ras in PDGF-stimulated fibroblasts and other cells.58 59 Tyrosine phosphorylation of the PDGFR is followed by SH2-mediated binding of PTP1D/Syp, recruitment of Grb2-SOS, and subsequent p21ras activation. Results reported here indicate that a similar signaling pathway is activated by IL-6 in U266 cells. Moreover, we have found that IL-6–stimulated PTP1D/Syp activation, as defined by tyrosine phosphorylation and interaction with gp130 and Grb2, is significantly impaired by IFN-β strongly suggesting that this interruption leads to the observed reduction in IL-6-induced p21ras and Erk2 activation.

Whether the catalytic activity of PTP1D/Syp mediates IL-6 signal transduction or functions by interrupting these signaling events in response to IFN-β remains to be determined. Because Kumar et al19 reported that IL-6 does not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of any of the members of the Src family of protein tyrosine kinases expressed in a subclone of U266 cells (AF10), it seems unlikely that dephosphorylation of the negatively regulating phosphotyrosine in these proteins would play any role. A more likely candidate substrate for PTP1D/Syp would be Jak2. Indeed Fuhrer et al65 recently described a direct physical association between Jak2 and PTP1D/Syp in IL-11–treated preadipocytes. We previously demonstrated that IL-6 and IL-11 induce common signaling molecules in murine plasmacytomas and hybridomas,7 making a physical association between Jak2 and PTP1D/Syp a reasonable possibility in IL-6–stimulated human myeloma cells. Additional support for this type of mechanism comes from the finding that the related SH2 domain-containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase PTP1C (also referred to as SHPTP1, HCP, and SHP) negatively regulates IFN signaling through dephosphorylation of Jak1.68

Besides PTP1D/Syp, Grb2 binds to additional tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins present in lysates from IL-6–induced U266 cells, including one or more proteins with molecular mass of approximately 145 kD. The significance of this binding is unknown at present, as we did not observe this association in vivo (ie, in Grb2 immunoprecipitations). A potential explanation for this discrepancy could be that there is a hierarchy of protein-protein interactions, which is not maintained under conditions of excess GST-Grb2 in vitro. Alternatively, the bacterially expressed GST-Grb2 may not faithfully mimic the endogenous protein.

Another protein known to function upstream of p21ras in several systems is the adaptor protein Shc.15,48 We have confirmed a prior report that IL-6 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of p52shc and its association with Grb2 in myeloma cells.19 We also found that IL-6 stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of the p46shc isoform and that the Shc proteins associate with a 145-kD tyrosine-phosphorylated protein(s). Interestingly, IFN-β treatment also stimulated the tyrosine phosphorylation of p52shc and p46shc, but inhibited IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of both p52shc and p46shc, as well as p145. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins of approximately 145-kD have been identified recently in other systems.60,62 Damen et al61 cloned p145 identifying it as an inositol tetraphosphate and phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate 5-phosphatase containing an NH2 -terminal SH2 domain, two target sites for PTB domains as well as a proline-rich region. Based on its characteristics they suggest that p145 regulates both Ras and inositol signaling pathways. It will be important to determine the relationship of p145 observed here to this 5-phosphatase. If p145 does function as a potential regulator of p21ras activity, it is plausible that the 45-kD tyrosine-phosphorylated protein that also coprecipitated with Shc proteins following IFN-β treatment may act by preventing the formation of IL-6–induced Shc-p145 complexes. In any event, these data implicate Shc as another potential point of convergence of the IL-6 and IFN-β signaling pathways in U266 cells.

It was recently reported that IFN-β activates Erk2 in U266 cells, inducing its association with Stat1α.36 We likewise observed activation of Erk2 following IFN-β challenge of our U266 cells (unpublished results, June 1995). Notably, activation of Erk2 by IFN-β differs in both magnitude and kinetics compared with that elicited by IL-6, with IL-6 inducing a more rapid and greater increase in Erk2 tyrosine phosphorylation. IFN-β also modified other signaling molecules used by IL-6 including induction of gp130 tyrosine phosphorylation, interaction of PTP1D with gp130 and Grb2 and Grb2-Shc association. The role of these modifications in IFN-β signaling and their contribution to IL-6/IFN-β crosstalk is currently under investigation.

In summary, the results presented here support a model in which IFN-β modifies the Ras-dependent ERK/MAP kinase pathway of IL-6 signaling in U266 cells. We propose that this occurs through the disruption of gp130-PTP1D/Syp-Grb2 and Grb2-Shc complexes. The partial inhibition of IL-6–induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak2 by IFN-β suggests that this kinase may be a primary target for the antagonistic IFN-β signaling effects. In this manner, IFN-β pretreatment downregulates IL-6–stimulated Jak2 phosphorylation of gp130 at sites necessary for association of PTP1D/Syp. The reduced phosphorylation of Jak2 may result from IFN-β–induced activation of a Jak2-specific phosphotyrosine phosphatase, with PTP1D/Syp itself being a candidate, or it may represent competition between Jak1/Tyk2 and Jak2 for gp130.64

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

Recently, Chin et al (Science 272:719, 1996) identified the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 as a primary target for IFN-γ–mediated cell growth suppression by STAT proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Jane McGlade for providing bacteria expressing the GST-Grb2 and GST-Grb2SH2 fusion proteins.

Supported in part by Grant No. 4510 from the National Cancer Institute of Canada (R.G.H.) and a fellowship from the Sunnybrook Trust for Medical Research (L.C.B.).

Address reprint requests to Robert G. Hawley, PhD, Oncology Research Laboratories, The Toronto Hospital, CRCS-424, 67 College St, Toronto, Ontario M5G 2M1, Canada.

![Fig. 1. IFN-β inhibits proliferation of U266 cells. U266 cells (3 × 105/mL) were incubated in medium containing 10% FCS for various times with (♦) or without (▪) IFN-β (200 U/mL). At the times indicated, [3H]thymidine (0.2 μCi/200 μL) was added for 18 hours and incorporated radioactivity measured as described in Materials and Methods.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/1/10.1182_blood.v89.1.261/2/m_bl_0023f1.jpeg?Expires=1767759979&Signature=tbySH1-~C~LGoZ6Wi1hVyuYalQzyabSz8fpqBoYud2XHfRGZ66pxsRpJRmVpfe62qfcvmpy8Hx~mX0KB8PLQD96in4KUAc~j0qwyPM8PrW0zJXyxds985HfG7x3BsODsiSHz2iXEReAq8WwecUzAdcEXUz6-X~D5K6ciTAtmRBauPh3CvmCAwC1-i3RdMKrmExdgIYA-930xRcAoW5o4O~vdHIq8QBHtSun~Y86~Zho0dxeUVxczjiGaZDVIqNkIZlNio2KgfTEmmWOF2ageXv311iUWM5Ss8fs1V7zs6mEZrA9SPJ~9fqlkJcs0IV3v2wgQQDjJY5GZ7SP5gDWt7A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal