In this issue of Blood, Bruno et al1 identify an enhancer that controls expression of nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) in multiple myeloma cells and demonstrate that targeting this enhancer can sensitize cells to bortezomib. Myeloma has been referred to as an enhanceropathy,2,3 based on the frequent structural variations juxtaposing oncogenes with potent enhancers. Fifty percent of myelomas are associated with clonal translocations in the IGH locus, however other plasma cell enhancers (IGL, IGK, and TENT5C) are also hijacked during myelomagenesis and can have clinical implications.4 These enhancers that drive oncogenes in myeloma are the target of thalidomide and its more potent analogs (collectively referred to as immunomodulatory drugs or cereblon E3 ligase modulatory drugs). Additionally, the study of noncoding regulatory RNAs that are associated with regions of accessible chromatin have been demonstrated to classify myeloma as well as gene expression itself. These regions were typically distal to coding genes and likely represent enhancers.3 Thus, the myeloma enhanceropathy extends beyond enhancers hijacked by translocations.

In the current study the authors look to extend these findings by performing the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) on plasma cells from 55 patients with myeloma to determine regions of accessible chromatin that change with disease progression. The authors also determine computationally, potential transcription factors that are regulating these sites through transcription factor (TF) motif analysis. From this they determined that the TF binding motifs clustered into three categories of which the second cluster had the highest penetrance across the samples. This cluster, which included factors that regulate essential processes such as the cell cycle and the TF binding motif that was ranked highest, was for NRF1.

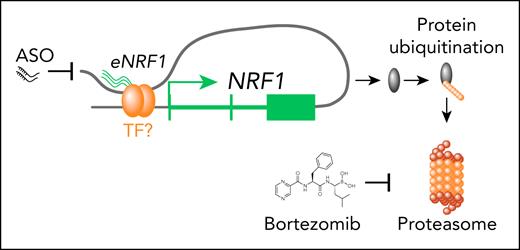

A protein called NRF1 that regulates expression of proteasome subunits has been implicated in responses to bortezomib, however that protein is encoded by the nuclear factor erythroid 2-like 1 gene (NFE2L1) and is distinct from the TF, encoded by NRF1.5 NRF1 is a TF that regulates the expression of genes involved in respiration, heme biosynthesis and mitochondrial replication.6 The authors show that NRF1 is an essential gene in cancer cell lines and silencing results in decreased proliferation of myeloma cells. Additionally, its expression increases during myeloma progression, and high expression is associated with worse outcomes. Therefore, they investigated the mechanism of NRF1 expression. Using a combination of approaches to determine chromatin regulation, they found that the NRF1 promoter had constitutive chromatin accessibility in all cells tested. However, analysis of HiChIP (chromatin immunoprecipitation and high-throughput chromatin interaction analysis) data demonstrated that a putative enhancer element ∼170 kb downstream of the NRF1 promoter was looped such that it contacted the promoter (see figure). The authors demonstrated that this region was accessible in their ATAC-seq analysis in myeloma samples but not MGUS samples suggesting that this enhancer element controlled the myeloma-specific expression. Consistent with this region being a NRF1 enhancer, they detected an enhancer RNA expressed from this element that also correlated with disease state. Targeting the expression of this enhancer RNA (eNRF1) resulted in decreased expression of NRF1 and diminished cell growth. Importantly, targeting eNRF1 was also effective in other tumor cell lines that expressed NRF1 but not in lines where this enhancer was not active.

NRF1 is an essential gene in cancer cell lines and silencing results in decreased proliferation of myeloma cells. The NRF1 promoter had constitutive chromatin accessibility in all the tested MM cells. An enhancer element ∼170 kb downstream of the NRF1 promoter was looped such that it contacted the promoter. This region was accessible in their ATAC-seq analysis in myeloma samples. Targeting the expression of this enhancer RNA (eNRF1) resulted in decreased expression of NRF1 and diminished cell growth. Importantly, targeting eNRF1 was also effective in other tumor cell lines that expressed NRF1 but not in lines where this enhancer was not active. Targeting NRF1 resulted in decreased protein ubiquitination and sensitized MM cells to bortezomib.

NRF1 is an essential gene in cancer cell lines and silencing results in decreased proliferation of myeloma cells. The NRF1 promoter had constitutive chromatin accessibility in all the tested MM cells. An enhancer element ∼170 kb downstream of the NRF1 promoter was looped such that it contacted the promoter. This region was accessible in their ATAC-seq analysis in myeloma samples. Targeting the expression of this enhancer RNA (eNRF1) resulted in decreased expression of NRF1 and diminished cell growth. Importantly, targeting eNRF1 was also effective in other tumor cell lines that expressed NRF1 but not in lines where this enhancer was not active. Targeting NRF1 resulted in decreased protein ubiquitination and sensitized MM cells to bortezomib.

Having determined that NRF1 is necessary for myeloma cell growth, its expression is associated with disease progression and how its expression is regulated, the authors turned their focus to understanding what genes NRF1 regulates in myeloma cells. To accomplish this, they performed ChIPseq for NRF1 in myeloma cell lines and determined which binding sites were in open chromatin regions in myeloma but not MGUS samples, from their ATAC-seq. This ultimately focused their analysis on 177 genes that were direct targets of NRF1 and demonstrated that this gene set was downregulated when NRF1 was silenced in cell lines. Like NRF1 itself, expression of this 177 gene set was associated with myeloma progression and outcome. Interestingly, the genes in this signature were enriched for protein ubiquitination, RNA splicing, and cell cycle and respiratory function. As protein production is a function that myeloma cells maintain from their cell of origin, the authors focused on protein ubiquitination and demonstrated decreased ubiquitinated proteins when NRF1 was silenced (see figure). This also resulted in the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). The sensitivity of myeloma cells to proteasome inhibition is at least in part due to protein production resulting in a requirement to maintain protein homeostasis.7-9 Therefore, the authors determined if NRF1 plays a role in sensitivity to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Similar to activation of stress protective pathways, NRF1 is upregulated following proteasome inhibition and silencing NRF1 sensitized cells to proteasome inhibition but not to thalidomide. This raised the possibility that targeting NRF1 could be a means to sensitize cells to proteasome inhibitors. Unfortunately, like most transcription factors, there are currently no small molecules to inhibit NRF1. However, gene expression can now be targeted using antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) and the authors approached this by targeting the eNRF1 enhancer with ASO. They provide evidence that the eNRF1 ASO results in decreased tumor growth and importantly, enhances the effect of bortezomib inhibition of tumor growth and survival in a xenograft model. Taken together, these studies point toward the potential opportunity to selectively target an undruggable transcription factor that is essential in myeloma by targeting a key regulator of its expression.

As impressive as these studies were, there remain questions to be answered. If loss of NRF1 results in decreased protein ubiquitination, how would this decreased proteasome load result in cells being sensitized to bortezomib? What are the key factors regulating NRF1, specifically at the eNRF1 enhancer? The mouse studies involved subcutaneous tumors, will this approach work in the context of systemic bone marrow disease? Will there be on-target, off-tumor effects that result in toxicity? To this end, if the eNRF1 enhancer is specific to multiple myeloma (MM; or other cancers) this may provide cell specificity to the author’s approach. Addressing these issues will be necessary for translation to the clinic, however the current studies open the possibility of targeting undruggable targets like NRF1 in a tumor-selective manner. This could include targeting the IGH enhancer that drives oncogenes in MM.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal