In this issue of Blood, Zhang et al introduce a new dimension to the intricate interplay between sensing mechanisms for oxygen and iron. They show how different affinities of an RNA stem-loop, iron-responsive element (IRE) on the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)2α subunit, to its binding proteins, the iron regulatory proteins IRP1 and IRP2, affect the systemic response to hypoxia.1

To ensure optimal cellular function, maintaining a precise balance of oxygen and nutrient concentrations is critical. The body uses intricate regulatory systems to monitor these concentrations, detect fluctuations, and initiate corrective responses to restore equilibrium. Intriguingly, there is tight cooperation between oxygen and iron regulation.

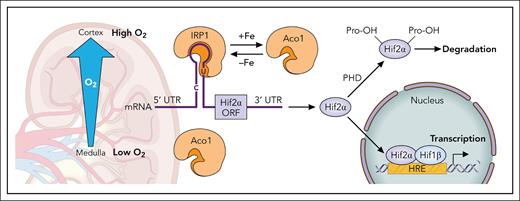

For effective oxygen supply, red blood cells are crucial. Erythropoietin (Epo), produced abundantly by peritubular interstitial Norn cells of the kidney, controls red blood cell production and ensures proper oxygen homeostasis. Epo production is controlled by the HIF complex, consisting of oxygen-sensitive α-subunits (HIF1α, HIF2α, or HIF3α) and a stable β-subunit (HIF1β). When oxygen levels are low, HIFα subunits translocate to the nucleus, form a complex with HIF1β, and bind to DNA, promoting transcription of numerous target genes, including EPO. In contrast, when oxygen is abundant, HIFα subunits are hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) and subsequently degraded. PHDs, which are iron dependent, become less effective under iron deficiency. In addition to this degradational regulation of all HIFα subunits, the main α-subunit in Norn cells, HIF2α, is regulated at the translational level by the IRE/IRP system.2-4

Erythropoiesis, the major iron-consuming process in mammalian organisms, is not only regulated by oxygen, but also by iron availability. Iron deficiency limits hemoglobin synthesis, reducing arterial oxygen concentration, and on a cellular level, many iron-dependent functions are impaired. Conversely, oxygen contributes to the regulation of iron uptake and recycling. In the intestinal epithelium, for example, HIF2α activation enhances dietary iron absorption.5,6 Furthermore, iron-oxygen interactions extend to regulatory proteins with iron-sulfur clusters, such as the F-box leucine rich repeat protein 5 (FBXL5), Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 4 (NCOA4), and IRP1.

The labile iron pool (LIP) is a cytosolic reservoir of loosely bound Fe2+, providing iron for various cellular functions. The IRE/IRP system senses the LIP and regulates iron import, export, and storage accordingly. IRP1 and IRP2 function as cytosolic RNA-binding proteins that maintain iron homeostasis by binding to IREs located in the 5’ or 3’ untranslated regions of several proteins involved in iron metabolism. In vitro studies indicated that the binding affinities of IRP1 and IRP2 for IREs on the ferritin subunits are similar, whereas IRP2 has a higher affinity for the transferrin receptor 1 IREs. Additionally, analysis of murine mRNAs identified several novel IRE candidates that either interact with both IRPs or prefer one over the other.7,8 Both IRPs respond to low LIP status, with increased RNA-binding activity, although they sense the LIP through different mechanisms. IRP1 functions as a cytosolic aconitase (Aco1) when it contains an Fe-S cluster and as an RNA-binding protein (IRP1) when it lacks the cluster. Typically, under physiological oxygen levels, IRP1 is in its Aco1 form. Higher oxygen and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) lead to the transition from Aco1 to IRP1. In contrast, IRP2 is degraded in response to high LIP, oxygen, and ROS/RNS levels. The physiological implication of the difference in oxygen sensing of IRP1 and IRP2 is that IRP2 dominates the regulation of iron homeostasis in most cell types. IRP1, in turn, has a high regulatory range for iron sensing, the higher the cellular oxygen levels are. IRP1 is highly expressed in the kidney, where a steep oxygen gradient from the outer region of the cortex to the medulla implies that its ability to sense iron will depend on its location within the tissue (see figure).

Regulation of the Hif2α subunit in the kidney. Translational regulation: Binding of IRP1 to the 5’ RNA stem-loop of Hif2α inhibits its translation. The conformational change of IRP1 between its RNA-binding form (IRP1) and its cytosolic Aco1 form is an iron-sensing mechanism that functions only in the presence of sufficient oxygen or reactive oxygen/nitrogen species. The steep oxygen gradient in the kidney suggests that the regulatory range of IRP1 may vary depending on its specific location within the tissue. Degradational regulation: All 3 Hifα subunits undergo degradational regulation by prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs), which are activated in the presence of oxygen and iron. HRE, hypoxia-responsive element; UTR, untranslated region. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Regulation of the Hif2α subunit in the kidney. Translational regulation: Binding of IRP1 to the 5’ RNA stem-loop of Hif2α inhibits its translation. The conformational change of IRP1 between its RNA-binding form (IRP1) and its cytosolic Aco1 form is an iron-sensing mechanism that functions only in the presence of sufficient oxygen or reactive oxygen/nitrogen species. The steep oxygen gradient in the kidney suggests that the regulatory range of IRP1 may vary depending on its specific location within the tissue. Degradational regulation: All 3 Hifα subunits undergo degradational regulation by prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs), which are activated in the presence of oxygen and iron. HRE, hypoxia-responsive element; UTR, untranslated region. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Zhang et al made a surprising observation: Although both, HIF2α and ferritin subunits have 5’ IREs, HIF2α levels were not elevated in kidneys of IRP2–/– mice, whereas ferritin subunits were highly elevated. IRP1 RNA-binding activity increased in the kidneys of IRP2–/– mice, suggesting a compensatory activation of IRP1 in this tissue. They discovered that the IRE on the HIF2α transcript binds with higher affinity to IRP1 than to IRP2, a difference attributed to a bulged uridine in the upper stem of the HIF2α IRE. These findings explain why IRP1–/– mice exhibit elevated Epo levels and erythrocytosis, whereas IRP2–/– mice experience a refractory anemia.9 The study offers a molecular explanation for the varying affinities of the HIF2α IRE for IRP1 and IRP2.

Although many genes with IREs are regulated by IRPs, the in vivo affinities of these IREs for each IRP remain underexplored. The proportion of HIF2α IREs within the total IRE pool varies between cell types, yet it is likely low in comparison to the highly expressed ferritin subunits, suggesting that gene-specific IRE affinities may impact the regulatory priorities of the IRE/IRP system. Investigating these affinities both in vitro and in vivo will deepen our understanding of the iron-oxygen regulatory balance.

The data further underline how affinity-differences for one or the other IRP influence the regulatory role of IRP1 and IRP2 under fluctuating oxygen levels. In the case of the HIF2α-IRE, which has a higher affinity for IRP1, hypoxia stabilizes IRP1 in its enzymatic Aco1 form, which does not bind RNA, thereby permitting the translation of HIF2α without inhibition. This shifts iron allocation toward erythropoiesis. In contrast, higher oxygen levels in the kidney enhance IRP1's regulatory capacity, leading to reduced erythropoiesis when iron stores are limited. Additionally, because IRP2 is degraded under high oxygen/ROS/RNS conditions and is not activated like IRP1, the IRP1/IRP2 ratio will impact how IRP-regulated genes respond to iron and oxygen fluctuations. For instance, the strong anti-inflammatory effect of IRP1 deletion in a Crohn disease mouse model might be due to HIF2α activation in intestinal epithelial cells.10

Conversely, high IRP2 levels in the brain could partially decouple HIF2α regulation from iron availability. HIF2α is highly expressed in brain blood vessels, where it seems important not to regulate its expression by iron, ensuring that the brain does not inappropriately neglect an adequate hypoxic response due to iron deficiency. Has the HIF2α IRE possibly evolved to evade repression by IRP2 in the brain?

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal