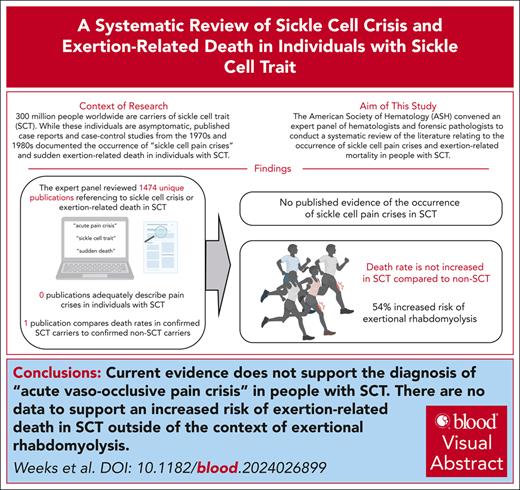

Visual Abstract

Globally, an estimated 300 million individuals have sickle cell trait (SCT), the carrier state for sickle cell disease (SCD). Although SCD is associated with increased morbidity and shortened life span, SCT has a life span comparable with that of the general population. However, “sickle cell crisis” has been used as a cause of death for decedents with SCT in reports of exertion-related death in athletes, military personnel, and individuals in police custody. To appraise this practice, the American Society of Hematology convened an expert panel of hematologists and forensic pathologists to conduct a systematic review of the literature relating to the occurrence of sickle cell pain crises and exertion-related mortality in people with SCT. Multiple bibliographic databases were searched with controlled vocabulary and keywords related to “sickle cell trait,” “vaso-occlusive pain,” and “death,” yielding 18 of 1474 citations. Independent pairs of reviewers selected studies and extracted data. We found no studies comparing uncomplicated acute pain crises in individuals with SCT and SCD. Additionally, no study was identified to support the occurrence of acute vaso-occlusive pain crises in individuals with SCT. Furthermore, this systematic review did not identify any evidence to support an association between SCT and sudden unexplained death in the absence of exertion-related rhabdomyolysis. We conclude that there are no data to support the diagnosis of acute vaso-occlusive sickle cell crisis as a cause of death in SCT, nor does the available evidence support the use of SCT as a cause of exertion-related death without rhabdomyolysis.

Introduction

Sickle cell trait (SCT) is the carrier state for sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited hemoglobinopathy caused by germ line pathogenic variants of the HBB gene, which encodes the β-globin proteins that form part of the hemoglobin tetramer. Individuals with SCD experience chronic hemolytic anemia, recurrent acute vaso-occlusive pain episodes (referred to here as acute pain crises), end-organ damage, and early mortality, with a median survival of 48 years at academic centers.1 Individuals with SCT do not have chronic hemolysis, the hallmark of SCD, and have the same life span as the general population.2 However, several case reports published in the 1970s and 1980s documented sudden exertion-related death3,4 or severe illness5,6 for individuals with SCT. Subsequently, excess exertion-related sudden death was reported in military recruits with SCT compared with individuals without SCT.7 High-profile out-of-season training deaths of National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes with SCT resulted in a requirement for documentation or a waiver for athletes with SCT wishing to participate in college sports.8,9 “In several cases of exertion-related death involving individuals with SCT, “sickle cell crisis” has been documented as the cause of death, and more recently, investigative journalists have uncovered 46 cases in which “sickle cell crisis” has been used as a cause of death for people with SCT who died while in police custody.”10,11 To critically appraise the validity of this practice, the American Society of Hematology convened an expert panel of hematologists and forensic pathologists to conduct a systematic literature review relating to the occurrence of acute vaso-occlusive sickle cell pain crises and exertion-related mortality in people with SCT.

Methods

Systematic review questions

The following PICO (population, intervention, comparator, outcome) questions were used to guide the systematic review:

Among individuals with SCT, compared with those with SCD, do uncomplicated acute pain crises occur?

Among individuals with SCT, compared with individuals without SCT, can physical activity above baseline result in sudden death?

For the purposes of question 1, “uncomplicated acute pain crises” are referred to as vaso-occlusive pain episodes, which, at diagnosis, are not complicated by other serious medical events, such as organ infarction, cancer, rhabdomyolysis, or infection. Noting that “sickle cell crisis” was occasionally used to describe more complicated clinical circumstances, as a supplementary analysis, we more broadly reviewed reports comparing mortality in individuals with and those without SCT.

Data sources and inclusion criteria

Best practices for conducting systematic reviews, consistent with the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook and the Evidence-based Practice Centers Methods Guide, were followed. This report follows the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting systematic reviews.12,13

The inclusion criteria consisted of articles published in English with documented laboratory testing for SCT and which reported the outcome variables of interest for PICO questions 1 and 2. Exclusion criteria included articles that did not report original data, did not include individuals with a confirmed laboratory diagnosis of SCT, or did not report exertion-related sudden death or acute pain crises.

When reviewing the literature for acute pain crises, we sought any documentation that may confirm the validity of diagnosing typical acute pain crises in SCT, including case reports. Publications reporting complicated pain presentations involving organ infarction, abdominal pain due to splenic sequestration, cancer, and rhabdomyolysis were not considered typical uncomplicated acute pain crises as observed in individuals with SCD and were excluded from review. We did not include case reports or case series when reviewing exertion-related sudden death because we focused on comparative risk measures.

A comprehensive language-agnostic search was conducted using several databases, with publication dates ranging from database inception to 18 October 2022. Included databases were Ovid MEDLINE (Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process, In-Data-Review and Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Daily), Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and conducted by a medical reference librarian. Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for SCT, pain, and mortality concepts. Section I of the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website, provides additional details regarding the search terms used and how they were combined.

Study selection and data extraction

Three pairs of independent reviewers evaluated the abstracts against the inclusion criteria. Abstracts considered potentially eligible by at least 1 reviewer were included for full-text review. The same pairs independently evaluated the full text of articles and determined final inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and consensus was reached after the reviewers had reviewed the article. Then, 2 reviewers extracted data from the final list of studies included in the systematic review.

Evaluation of study quality

The risk of bias in studies was evaluated by 2 reviewers using items derived from the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (for comparative studies evaluating mortality)14 and from a tool specific for case series (for noncomparative studies reporting pain episodes).15 From the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, we considered the documentation of SCT status (eg, by self-report, medical record review, or laboratory testing) to be the key factor in determining overall study quality and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Synthesis methods

Inconsistent study methods and outcome reporting precluded meta-analysis. Data were summarized narratively. The certainty in evidence was judged following the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) for systematic reviews without a feasible meta-analysis.16

Results

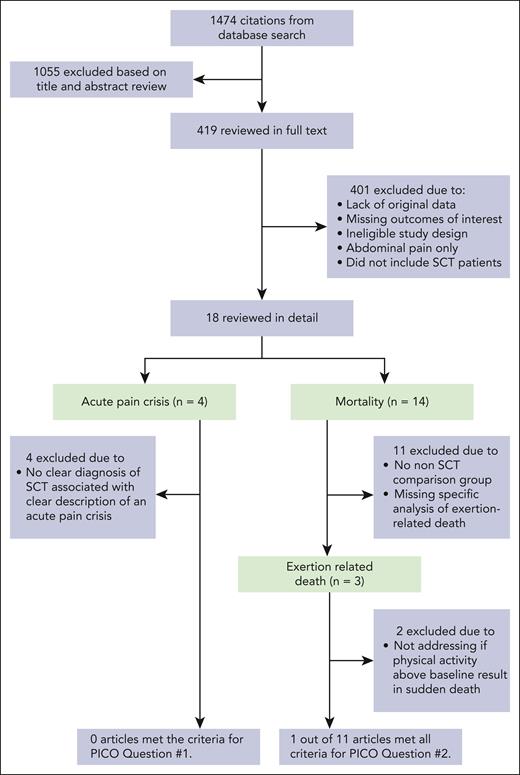

The search identified 1474 citations, of which 7 met the criteria for inclusion and analysis based on the 2 prespecified systematic review questions (Figure 1). The main reasons for excluding references were lack of original data, insufficient laboratory data to support the diagnosis of SCT, missing outcomes of interest, or reporting only on abdominal pain that may have been related to splenic ischemia or infarction.

Flow diagram illustrating the process of study selection and reasons for exclusion. PICO clinical questions are structured using the mneumonic P (population), I (intervention), C (comparator), and O (outcome).

Flow diagram illustrating the process of study selection and reasons for exclusion. PICO clinical questions are structured using the mneumonic P (population), I (intervention), C (comparator), and O (outcome).

Acute vaso-occlusive pain episodes related to SCT compared with SCD

None of the included studies assessed acute pain events directly related to acute vaso-occlusive episodes (acute pain crises) in individuals with SCT compared with individuals with SCD (question 1). Thus, we did not find any evidence that pain crises occur among individuals with SCT, compared with those with SCD. We identified 4 publications that purported to describe SCT-related uncomplicated acute pain crises.17-20 This included 2 case reports, 1 prospective cohort study, and 1 case-control study. The methodological quality of these 4 studies is summarized in Table 1. These 4 studies lacked a clear diagnosis of SCT associated with a clear description of an acute vaso-occlusive pain crisis. A more detailed description of the studies and their limitation is provided in section II of the supplemental Methods. The certainty of evidence derived from these reports was very low and thus could not address question 1.

Included studies reporting on the outcome of acute pain episodes

| Study . | Design . | Population . | Key findings and clinical descriptions . | Description of physical activity/trigger . | Diagnosis of SCT . | Is description of episode diagnostic of pain/vaso-occlusive episode (as typically observed in SCD)? . | Is the reported population representative of the whole experience of the authors (as in a consecutive or random sample)? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biedrzycki et al20 | Case report | A case report of 51-y-old Afro-Caribbean man with SCT | The patient had diabetes and presented acutely with hyperosmolar nonketotic acidosis. He rapidly deteriorated with multiorgan failure after hospital admission. Autopsy demonstrated sickled erythrocytes within the vasculature. The authors also report that the patient had “acute chest syndrome” without any clinical information to support this diagnosis. No prodrome of pain is presented. | Acute illness | History | No | No |

| Taksande et al19 | Case report | A case report of a single 35-y-old woman with “hemoglobin AS pattern on electrophoresis” from India | The patient reported low back pain for 6 mo while walking with relief in the supine position. Examination revealed pallor, hemoglobin of 6.5 g/dL and MCV of 77 fl. Peripheral smear was consistent with microcytic hypochromic anemia. Peripheral blood smear shows hypochromic microcytic anemia. MRI of the spine showed marrow necrosis in lumbar vertebrae, suggestive of cystic hemorrhagic necrosis of bone, which the authors attribute to sickle cell status. | Not described | Laboratory, electrophoresis | No | No |

| Dora et al18 | Prospective cohort | 119 peripartem females with SCT in India at an academic hospital | The authors report 5 individuals with pain and 1 with “acute chest syndrome” without detailed clinical description of either pain episodes or acute chest syndrome cases. | Pregnancy | Laboratory, HPLC | No | Yes |

| Souza et al17 | Case-control∗ | Cases: 31 individuals with SCT from 2 cities in Brazil Controls: archived frozen samples without SCT | The authors report that 22 of 31 individuals with SCT reported pain in clinical examination. The authors note that pain is in the upper and lower limbs and joints. Beyond this, no other clinical description is provided. | Not described | Laboratory, PCR | No | No |

| Study . | Design . | Population . | Key findings and clinical descriptions . | Description of physical activity/trigger . | Diagnosis of SCT . | Is description of episode diagnostic of pain/vaso-occlusive episode (as typically observed in SCD)? . | Is the reported population representative of the whole experience of the authors (as in a consecutive or random sample)? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biedrzycki et al20 | Case report | A case report of 51-y-old Afro-Caribbean man with SCT | The patient had diabetes and presented acutely with hyperosmolar nonketotic acidosis. He rapidly deteriorated with multiorgan failure after hospital admission. Autopsy demonstrated sickled erythrocytes within the vasculature. The authors also report that the patient had “acute chest syndrome” without any clinical information to support this diagnosis. No prodrome of pain is presented. | Acute illness | History | No | No |

| Taksande et al19 | Case report | A case report of a single 35-y-old woman with “hemoglobin AS pattern on electrophoresis” from India | The patient reported low back pain for 6 mo while walking with relief in the supine position. Examination revealed pallor, hemoglobin of 6.5 g/dL and MCV of 77 fl. Peripheral smear was consistent with microcytic hypochromic anemia. Peripheral blood smear shows hypochromic microcytic anemia. MRI of the spine showed marrow necrosis in lumbar vertebrae, suggestive of cystic hemorrhagic necrosis of bone, which the authors attribute to sickle cell status. | Not described | Laboratory, electrophoresis | No | No |

| Dora et al18 | Prospective cohort | 119 peripartem females with SCT in India at an academic hospital | The authors report 5 individuals with pain and 1 with “acute chest syndrome” without detailed clinical description of either pain episodes or acute chest syndrome cases. | Pregnancy | Laboratory, HPLC | No | Yes |

| Souza et al17 | Case-control∗ | Cases: 31 individuals with SCT from 2 cities in Brazil Controls: archived frozen samples without SCT | The authors report that 22 of 31 individuals with SCT reported pain in clinical examination. The authors note that pain is in the upper and lower limbs and joints. Beyond this, no other clinical description is provided. | Not described | Laboratory, PCR | No | No |

HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Pain evaluation not comparative.

Death among individuals with SCT, compared with individuals without SCT, while participating in physical activity

A total of 14 studies were identified describing death in individuals reported to have SCT (supplemental Table 1).2,7,21-33 Among these 14 studies, 3 met the initial requirements for inclusion. However, of the 3 studies,7,21,22 only 1 met all the necessary criteria to address question 2.22Table 2 summarizes the methodological quality of the 3 reviewed reports. Detailed description of the limitations of the other 2 studies is included in section II of the supplemental Methods. In the 1 retrospective cohort study that met the criteria for inclusion, 47 944 Black soldiers in the Stanford Military Data Repository identified from January 2011 to December 2014 had laboratory confirmation of SCT status performed. The Stanford Military Data Repository comprises all digitally recorded health encounters (inpatient and outpatient, within military facilities or purchased from civilian institutions) for all active-duty soldiers in the US Army. Universal precautions to prevent heat injury were implemented during this time frame. The study reported that SCT was not associated with overall mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 0.99; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46-2.1, P = .97), with similar HRs observed for battle-related and non–battle-related deaths.22 SCT was associated with a 54% higher risk of heat-related exertional rhabdomyolysis (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.12-2.12; P = .008). Therefore, we found no evidence that physical activity above baseline results in sudden death among individuals with SCT in the absence of rhabdomyolysis. Limitations of the other 2 studies to address question 2 are described in section II of the supplemental Methods and details about excluded studies on mortality in SCT are included in supplemental Table 1. The certainty of evidence was low due to the observational nature of these reports and plausible confounding.

Studies reporting on the outcome of exertion-related mortality

| Study . | Design . | Study population . | Primary outcome(s) investigated . | Method of SCT diagnosis . | Described perimortem physical activity or triggers . | Method used to ascertain the primary outcome . | Are compared populations representative? . | Are covariates considered in the analysis? . | Is the distribution of potential covariates similar in compared populations?1 . | Key findings (narrative) . | Reported associations . | Is the reported association adjusted for covariates? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson et al22 | Case-control | Active-duty Black soldiers in the US Army, 2011-2014 Universal precautions to prevent heat injury were implemented during this time frame | Any death Battle-related death Non–battle-related death Exertional rhabdomyolysis | Laboratory | Not described | Laboratory | Yes | Duration of service, physical conditioning, BMI, self-reported tobacco use | Yes | Similar rates of any death, battle-related death, and non–battle-related deaths, among Black soldiers with and without SCT Increased rate of exertional rhabdomyolysis among Black recruits with vs those without SCT | Any death: HR, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.46-2.13) Battle-related death: HR, 0.96 (95% CI, 0.13-7.3) Non–battle-related death: HR, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.43-2.27) Exertional rhabdomyolysis: HR, 1.54 (95% CI, 1.12-2.12) | Yes |

| Kark et al7 | Case-control | Enlisted US Armed Forces recruits during basic training (1977- 1981) | Exertion-related sudden death | History | Exercise | Autopsy and clinical records | No, only confirmed deaths were tested for SCT. All other participants’ SCT status inferred. | Race and age | Not presented | 13 total sudden deaths reported in Black recruits with SCT Increased relative risk of cardiac and heat-related sudden death in SCT vs non-SCT Cardiac and heat-related sudden death: RR 34.9 (95% CI, 6-38) in Black recruits and 33.7 (95% CI, 11-478) in all recruits | Any sudden death: RR, 39.8 (95% CI, 19.1-82.7) Sudden death among Black recruits: RR, 27.6 (95% CI, 10.2-75.1) | Stratified analysis by race and age |

| Kark et al21 | Case-control | Enlisted US Armed Forces recruits during basic training (1968- 1986) | Exertion-related sudden death | History | Exercise | Autopsy and clinical records | No, only confirmed deaths were tested for SCT. All other participants’ SCT status inferred. | Race and age | Not presented | 24 Deaths with SCT and 31 without SCT Stratified analysis by age group showing that the risk of death increases with age | Any sudden death: RR, 39.8 (95% CI, 17-90) Sudden death among Black recruits: RR, 28 (95% CI, 9-100) | Stratified analysis by race and age |

| Study . | Design . | Study population . | Primary outcome(s) investigated . | Method of SCT diagnosis . | Described perimortem physical activity or triggers . | Method used to ascertain the primary outcome . | Are compared populations representative? . | Are covariates considered in the analysis? . | Is the distribution of potential covariates similar in compared populations?1 . | Key findings (narrative) . | Reported associations . | Is the reported association adjusted for covariates? . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson et al22 | Case-control | Active-duty Black soldiers in the US Army, 2011-2014 Universal precautions to prevent heat injury were implemented during this time frame | Any death Battle-related death Non–battle-related death Exertional rhabdomyolysis | Laboratory | Not described | Laboratory | Yes | Duration of service, physical conditioning, BMI, self-reported tobacco use | Yes | Similar rates of any death, battle-related death, and non–battle-related deaths, among Black soldiers with and without SCT Increased rate of exertional rhabdomyolysis among Black recruits with vs those without SCT | Any death: HR, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.46-2.13) Battle-related death: HR, 0.96 (95% CI, 0.13-7.3) Non–battle-related death: HR, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.43-2.27) Exertional rhabdomyolysis: HR, 1.54 (95% CI, 1.12-2.12) | Yes |

| Kark et al7 | Case-control | Enlisted US Armed Forces recruits during basic training (1977- 1981) | Exertion-related sudden death | History | Exercise | Autopsy and clinical records | No, only confirmed deaths were tested for SCT. All other participants’ SCT status inferred. | Race and age | Not presented | 13 total sudden deaths reported in Black recruits with SCT Increased relative risk of cardiac and heat-related sudden death in SCT vs non-SCT Cardiac and heat-related sudden death: RR 34.9 (95% CI, 6-38) in Black recruits and 33.7 (95% CI, 11-478) in all recruits | Any sudden death: RR, 39.8 (95% CI, 19.1-82.7) Sudden death among Black recruits: RR, 27.6 (95% CI, 10.2-75.1) | Stratified analysis by race and age |

| Kark et al21 | Case-control | Enlisted US Armed Forces recruits during basic training (1968- 1986) | Exertion-related sudden death | History | Exercise | Autopsy and clinical records | No, only confirmed deaths were tested for SCT. All other participants’ SCT status inferred. | Race and age | Not presented | 24 Deaths with SCT and 31 without SCT Stratified analysis by age group showing that the risk of death increases with age | Any sudden death: RR, 39.8 (95% CI, 17-90) Sudden death among Black recruits: RR, 28 (95% CI, 9-100) | Stratified analysis by race and age |

BMI, body mass index; HR, hazard ratio; RR, risk ratio.

Discussion

In this study, an expert panel of hematologists and forensic pathologists systematically reviewed the literature to determine whether uncomplicated acute vaso-occlusive pain crises are a clinical entity in individuals with SCT, compared with individuals with SCD, and to examine the occurrence of sudden death after physical exertion in SCT, compared with individuals without SCT.

Our review demonstrates that individuals with SCT do not have documented spontaneous, uncomplicated acute pain crises. No published studies were identified comparing the occurrence of acute sickle cell crises in individuals with laboratory-confirmed SCT with those with SCD. Moreover, the identified case reports were flawed by a range of factors, including the absent or insufficient use of SCT diagnostics,20 clinical scenarios that were either inconsistent with19 or inadequate for hematology expert confirmation of the diagnosis of a typical acute sickle cell crisis,17,18 or both. Pain in the context of other medical issues can occur among patients with SCT. For instance, 1 study we reviewed reported pain in a patient with hyperosmolar nonketotic acidosis and acute illness (section II, supplemental Methods). In addition, multiple case reports and case series (excluded from this systematic review) document abdominal pain or splenic infarction in individuals with SCT after traveling to high altitude areas with low oxygen tension.34-38 Whether extreme conditions result in an increased risk of pain that can be causally linked to the diagnosis of SCT has not been systematically evaluated.

We found no data supporting an association between SCT and sudden unexplained death. One large retrospective cohort analysis that met all of our inclusion criteria did not document acute sickle cell crises as a cause of death in any of the decedents with SCT.7,22 Other studies examining the risk of death in SCT suffer from inferred SCT diagnosis among surviving cases and all controls, as well as the conflation of sudden unexplained death with death from heat injury or rhabdomyolysis. Importantly, after the implementation of universal precautions to prevent heat- and environment-related injury in military personnel, the race-adjusted risk of death was no different in individuals with SCT compared with individuals without SCT.22

During our systematic literature review, we identified multiple reports in which sickled erythrocytes at autopsy were erroneously cited as evidence of widespread antemortem sickle cell crises.20,28,29,31 Mechanistically, extreme combinations of heat, dehydration, and high-intensity exercise are postulated to trigger erythrocyte sickling that is etiologically linked to exertion-related morbidity and mortality in individuals with SCT.39 We have found no human data to support this hypothesis. None of the literature provides clinical descriptions sufficient to make a diagnosis of an acute pain crisis immediately preceding death. Although hemoglobin S in SCT does polymerize under hypoxic or acidic conditions,40,41 the degree of polymerization is less than that observed in SCD.41 In all decedents, oxygen saturation will fall <60%, the threshold required to observe erythrocyte sickling in SCT,41 and sickling of <1% of red cells may occur during exercise in individuals with SCT.42,43 Thus, the preponderance of the evidence indicates that sickled erythrocytes at autopsy are emblematic of perimortem systemic hypoxemia, a pathophysiologic end point for all deaths. Therefore, sickled cells in the microvasculature are an expected artifact on autopsy 44 and on their own are an insufficient biomarker for the cause of death.

The paucity of direct evidence derived from high-quality peer-reviewed literature is the primary limitation when addressing the 2 major questions in the systematic review. However, modern frameworks for evaluating certainty of evidence and decision-making (ie, GRADE) promote indirect evidence when direct evidence is sparse. Other adaptions of GRADE that have used indirect evidence to support clinical decision-making include the Clinical Practice Guideline Manual from the American Academy of Family Physicians and the World Health Organization Handbook for Guideline Development (Guideline Review Committee Handbook).45,46 Both panels encouraged evidence-based practitioners to consider factors other than the published literature, including indirect evidence, when recommending. We applied the GRADE approach, leveraging the panel’s extensive multidisciplinary clinical expertise. This enabled the group to address the absence of direct evidence and the abundance of indirect evidence and clinical experience that SCT is not associated with acute uncomplicated acute sickle cell crises and death.

After completing a systematic review, the American Society of Hematology multidisciplinary expert panel found no published data to support the occurrence of acute vaso-occlusive sickle pain crises among individuals with SCT. Furthermore, the panel found no evidence of death associated with physical exertion in the absence of rhabdomyolysis. Postmortem assessment in decedents with SCT should include an evaluation for rhabdomyolysis and attention to environmental and clinical findings associated with heat-related exertional illness. We conclude that there is no evidence to support the use of the terms “vaso-occlusive pain episode,” “sickle cell crisis,” “exertional sickling with SCT,” or any similar terminology on the death certificates of individuals with SCT.

Authorship

Contribution: L.D.W., M.H.M., R.P.N., and M.R.D. designed the study; L.D.W., A.C.W., M.H.M., R.P.N., Y.E., and M.R.D. screened citations for study inclusion; L.D.W., M.H.M., and M.R.D. extracted and summarized data from included citations; L.D.W. prepared the initial manuscript draft; all authors reviewed and proposed revisions to the manuscript; L.D.W., M.R.D., and M.H.M. reconciled the rounds of author revisions and prepared the manuscript for submission; M.R.D. was chair of the American Society of Hematology's systematic review panel; and all authors convened as a committee to conceive the idea for the review, critically reviewed the data, and approved the manuscript for final submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.D.W. reports consultancy for AbbVie, Vertex, and Sobi, all unrelated to this work. M.V. reports consultancy for Vertex, Novo Nordisk, and Bristol Myers Squibb, all unrelated to this work. P.T.M. reports research funding from Novartis, unrelated to this work. A.C.W. reports consultancy for Sanofi, Genentech, Sobi, Novo Nordisk, Takeda, and Spark and research funding from Pfizer, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, and Takeda, unrelated to this work. M.R.D. reports participating on a Novartis clinical trial steering committee; these activities are not directly related to this work. At the time of publication, A.U.Z. is an employee of and has equity in Agios Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lachelle D. Weeks, Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, DA 1133, Boston, MA 02215; email: lachelle_weeks@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

C.D. and R.A.M. are joint senior authors.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Comments

Sickle Cell Trait, Certainty, and Forensic Semantics: A Philosophical Clarification

This correspondence addresses significant epistemological, methodological, and medico-legal concerns regarding the article by Weeks et al., entitled “Sickle cell trait does not cause ‘sickle cell crisis’ leading to exertion-related death: a systematic review,” published in Blood (2025;145[13]:1345–1352).

The article’s conclusion—that sickle cell trait (SCT) is not causally related to sickle cell crises or exertion-related deaths—is presented with a level of certainty that is epistemologically problematic. The concept of 'certainty' is apophantic by nature: it is not a matter of gradation or probability. To suggest that a conclusion is of 'very low certainty' is a misuse of the term. What is being measured is not certainty, but the quality of evidence, which, by the authors’ own account, is based on limited and low-quality studies.

Moreover, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. The epistemic structure of probabilistic claims must not be confused with definitive negation, especially in contexts with forensic and legal implications. The interpretation of 'no association' in this case could be dangerously misapplied in judicial settings, leading to misinformed conclusions about the causes of death in individuals with SCT.

Additionally, it is unclear whether this systematic review protocol was preregistered in PROSPERO or another appropriate registry, as is required by current methodological standards. The absence of protocol preregistration represents a significant limitation, further undermining confidence in the findings, particularly given the potential forensic consequences.

In medicine—and particularly in forensic contexts—semantic precision is not optional. The distinction between 'proof' and 'evidence', as well as the careful use of terms such as 'certainty', is crucial. To conflate these notions may generate epistemic injustice or produce misleading inferences in judicial cases involving sudden death and SCT.

This Letter does not report new data. It is submitted solely to clarify foundational epistemological and semantic concerns that affect the interpretation and application of the original article.

Thank you for your attention to this important matter.

Sincerely,

Arturo Martí-Carvajal, MD,MSc,PhD

arturo.marti.carvajal@gmail.com /amarti@edu.uc.edu