Key Points

Differentiation bias of hematopoietic stem cells alone is an insufficient explanation for myeloid bias among multipotent progenitors.

Proliferation of early myeloid-primed progenitors also contributes to myeloid bias with NFκB dysregulation, aging, and malignancy.

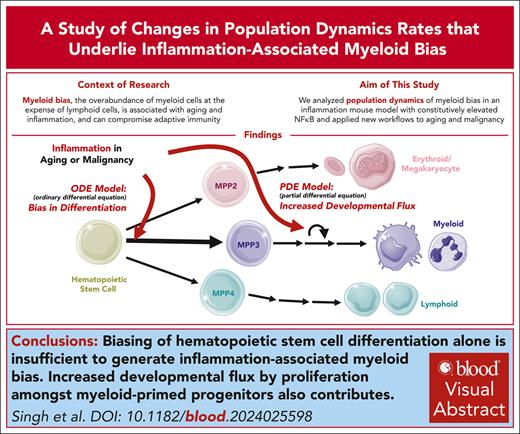

Visual Abstract

Aging and chronic inflammation are associated with overabundant myeloid-primed multipotent progenitors (MPPs) among hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Although hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) differentiation bias has been considered a primary cause of myeloid bias, whether it is sufficient has not been quantitatively evaluated. Here, we analyzed bone marrow data from the IκB− (Nfkbia+/−Nfkbib−/−Nfkbie−/−) mouse model of inflammation with elevated NFκB activity, which reveals increased myeloid-biased MPPs. We interpreted these data with differential equation models of population dynamics to identify alterations of HSPC proliferation and differentiation rates. This analysis revealed that short-term HSC differentiation bias alone is likely insufficient to account for the increase in myeloid-biased MPPs. To explore additional mechanisms, we used single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) measurements of IκB− and wild-type HSPCs to track the continuous differentiation trajectories from HSCs to erythrocyte/megakaryocyte, myeloid, and lymphoid primed progenitors. Fitting a partial differential equations model of population dynamics to these data revealed not only less lymphoid-fate specification among HSCs but also increased expansion of early myeloid-primed progenitors. Differentially expressed genes along the differentiation trajectories supported increased proliferation among these progenitors. These findings were conserved when wild-type HSPCs were transplanted into IκB− recipients, indicating that an inflamed bone marrow microenvironment is a sufficient driver. We then applied our analysis pipeline to scRNA-seq measurements of HSPCs isolated from aged mice and human patients with myeloid neoplasms. These analyses identified the same myeloid-primed progenitor expansion as in the IκB− models, suggesting that it is a common feature across different settings of myeloid bias.

Introduction

Myeloid bias, the overabundance of myeloid cells at the potential expense of lymphoid cells, is associated with aging in both humans1,2 and mice3-5 and can compromise adaptive immunity, such as vaccine responses and infection resistance.6 Myeloid bias has also been observed in patients with inflammatory diseases or mouse models of such diseases.7-11 Hematopoietic cells are responsive to inflammatory cytokines12-16 and toll-like receptor ligands,17,18 which can induce myeloid cell production.

Early hematopoietic progenitor abundances change with aging19,20 and inflammation,15 affecting bone marrow output. Several studies have characterized subsets of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), defined by cell-surface markers, in terms of different differentiation potential.21-25 Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are multipotent and include long-term HSCs, capable of hematopoietic reconstitution, and their immediate short-term HSC progeny, with more limited self-renewal capacity. ST-HSCs differentiate into multipotent progenitors (MPPs), which are further categorized by differentiation biases: MPP2s are primed to generate megakaryocytes and erythrocytes, MPP3s to granulocytes and monocytes, and MPP4s to lymphocytes.25 Although HSC differentiation lineage bias is an acknowledged contributor to myeloid bias in early hematopoiesis,26 it is unclear whether it is a sufficient explanation.

Quantification of population dynamic rates from cell-count data requires a mathematical model. Previous modeling work has interrogated the steady-state dynamics of hematopoiesis in vivo.27,28 Using inducible genetic labeling of HSCs and recording the number of labeled cells over time, net proliferation and differentiation rates were estimated.27 This same study made measurements in aged mice and identified decreased MPP differentiation into common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs). However, this work did not differentiate MPP subpopulations. A more recent study integrated genetic labeling with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) in young and aged mice,29 permitting finer resolution of HSPC heterogeneity. However, without a mathematical model, potential differences in population dynamics could not be discerned.

Given the association with inflammation, we studied population dynamics of myeloid bias in a tractable mouse model with constitutively elevated NFκB, IκB− (Nfkbia+/−Nfkbib−/−Nfkbie−/−, described in Chia et al30). NFκB-signaling dysregulation has been implicated in aging31,32 and malignancy33-35 and can mediate cytokine production that promotes myelopoiesis.36 We analyzed HSPC counts in IκB− using a mathematical model and established that ST-HSC differentiation bias is likely insufficient to explain the increase in MPP3s. Using scRNA-seq measurements of IκB− and wild-type (WT) HSPCs, we found that early expansion among myeloid-primed progenitors also contributes and differentially expressed genes along this lineage supported increased proliferation. These population dynamics changes were conserved when WT HSPCs were transplanted into IκB− recipients. Remarkably, model-aided analyses detected this myeloid-primed progenitor expansion in scRNA-seq measurements of HSPCs from aged mice and human patients with myeloid neoplasm. Together, these analyses demonstrate that inflammatory signaling promotes myeloid bias not only through biasing HSC differentiation but also through enhanced expansion of early myeloid-primed progenitors.

Methods

Flow cytometry and cell quantification

HSPCs (Lin−/Sca1+ cKithi gate) were collected and enumerated (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website) by multiplying the percentage of the total gated population by the absolute bone marrow cell counts in the bilateral femurs and tibias.30

ODE model of HSPC population dynamics

Here, and , are net proliferation and differentiation rates, respectively, and (branching-ratio) describes the ST-HSC proportion differentiating into each MPP population. Assuming steady-state such as in previous work,27 we derived relationships relating rate parameters to cell counts (supplemental Information, Eq. 1.6-1.9). We compared counts between conditions to determine potential rate changes (supplemental Information, Eqs. 2.1-3.5).

HSPC collection and scRNA-seq data processing

Approximately 30 000 HSPCs sorted from WT or IκB− mice were barcoded and pooled for sequencing37 (as in Chia et al30). Single-cell transcriptome and feature barcode libraries were generated using Chromium Next GEM38 Single Cell 3ʹ Reagent Kits (v.3.1), paired-end sequenced (50 bp) by the University of California Los Angeles Technology Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics core facility: NovaSeqSP system, and counts were quantified by CellRanger (v.7.0).38 Quality control criteria based on minimum unique molecular identifier, percent mitochondrial counts, and potential doublets were applied (see the supplemental Information; GEO: GSE262024). Principal component analysis (PCA) was calculated from 115 hematopoietic genes (supplemental Table 2), and WT HSPCs were used for Slingshot.39 IκB− and published data were projected onto the pseudotime trajectories, and cell densities were obtained by sampling lineage weights and applying a kernel density estimate40 (see the supplemental Information).

PDE model of HSPC population dynamics

Here, is pseudotime and and are now functions of . Before the branch-point, the rates are shared across lineages (erythrocyte/megakaryocyte-primed, myeloid-primed, and lymphoid-primed) and the densities summed to form the HSC lineage. Solving for steady state, we derived relationships between the rate functions and cell-density changes between conditions and fit these to the experimental densities (supplemental Information, Eq. 4.5-4.14).

Code for fitting models, pseudotime analysis, and cell-density calculation is provided at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11043829.

Differential gene expression along lineages (LineageDE)

A negative binomial generalized-additive model (NB-GAM) was fit to gene expression along pseudotime (supplemental Information, Eq. 6.1-6.4).41-43 We evaluated the likelihood ratio test statistic between models with different or shared coefficients across conditions. We sampled cells with replacement and reperformed the pseudotime analysis 100 times for a permutation test to incorporate uncertainty in pseudotime assignments43 (see the supplemental Information). LineageDE is available at https://github.com/apekshasingh/LineageDE.

Results

Bias in HSC differentiation is insufficient to explain altered MPP populations

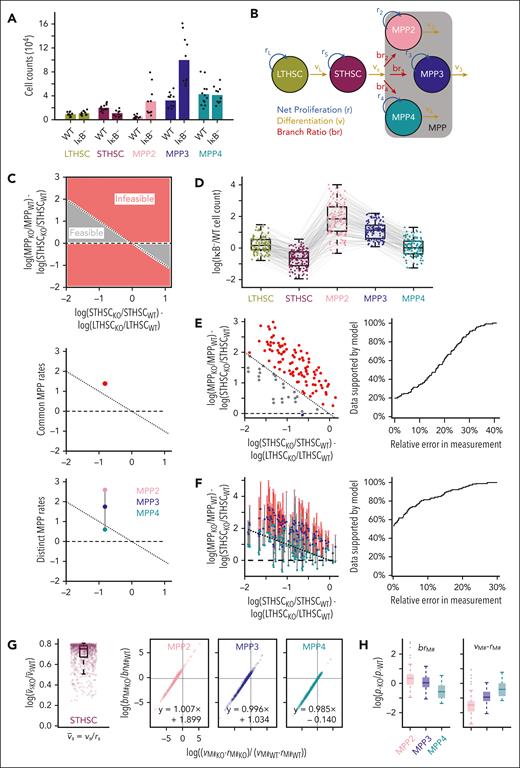

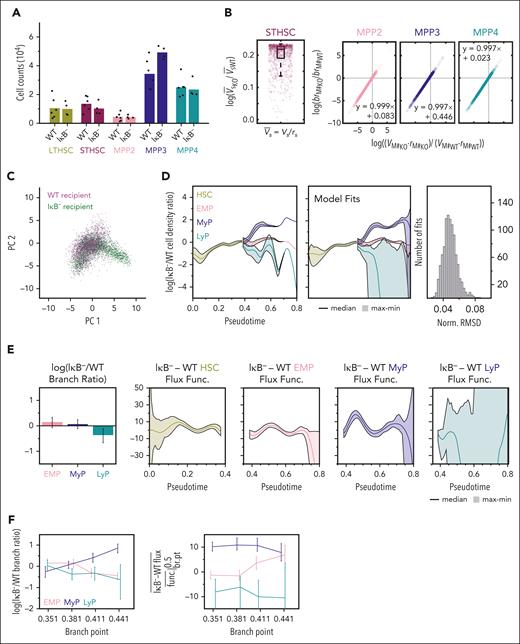

We focused on a mouse model of inflammation induced by IκB deficiency to investigate how the dynamics of hematopoiesis are altered in myeloid bias. HSPC subpopulation quantification by flow cytometry revealed an increase in MPP2s and MPP3s30, indicating myeloid bias (Figure 1A). To understand how dynamic rate changes could account for the observed cell-count differences in IκB− vs WT, we constructed an ODE model of HSPC differentiation (Figure 1B; Eq. 1.1-1.5). This model includes net proliferation (division rate - death rate) and differentiation rates for each cell type, including a branching ratio that describes ST-HSC propensity to differentiate into each MPP.

Bias in HSC differentiation is insufficient to explain altered MPP populations. (A) Average HSPC subpopulation counts in IκB− (n = 10) vs WT (n = 12) with individual data points overlaid. (B) Schematic of ODE model of early hematopoiesis. (C) Regions of feasible/infeasible observations under a model that only permits the rate and differentiation bias of ST-HSCs to vary between WT and IκB− (top). The MPP rates of differentiation and net proliferation are the same between WT and IκB− for these analyses. Mean values collapsing MPP subpopulations (assuming common rates of differentiation and net proliferation across the 3 MPP subpopulations) is infeasible (middle). Mean values allowing distinct rates for each MPP subpopulation (that are then equivalent across experimental conditions) is feasible (line connecting values passes through feasible region) (bottom). (D) HSPC subpopulation cell-count ratios between IκB− and WT. Each IκB− animal was compared with each WT animal resulting in 120 sets of data points. Gray lines connect cell-count ratios originating from a single IκB− and WT pair. (E) Scatterplot of 120 observations on feasibility map (left) with common rates across MPPs. Only 24 (gray) are feasible. Most have an increase in IκB− MPPs that exceeds what is permissible (red). Allowing for measurement error, a relative error rate of nearly 40% is needed to account for all data under the restricted model (right). (F) Scatterplot of 120 observations on feasibility map (left) with distinct rates across MPPs; 64 (gray) are feasible and a relative error rate near 27% is needed to account for all data (right). (G) Parameter fits to the average cell counts for a model where ST-HSC differentiation and branching ratio is allowed to vary between IκB− and WT, as well as the rate parameters for each MPP population. Formula for line of best fit specified for MPP parameters. (H) Top 10% of parameter fits in (G) ordered by smallest total difference (absolute value of the logarithm of ratios) between IκB− and WT parameters (p).

Bias in HSC differentiation is insufficient to explain altered MPP populations. (A) Average HSPC subpopulation counts in IκB− (n = 10) vs WT (n = 12) with individual data points overlaid. (B) Schematic of ODE model of early hematopoiesis. (C) Regions of feasible/infeasible observations under a model that only permits the rate and differentiation bias of ST-HSCs to vary between WT and IκB− (top). The MPP rates of differentiation and net proliferation are the same between WT and IκB− for these analyses. Mean values collapsing MPP subpopulations (assuming common rates of differentiation and net proliferation across the 3 MPP subpopulations) is infeasible (middle). Mean values allowing distinct rates for each MPP subpopulation (that are then equivalent across experimental conditions) is feasible (line connecting values passes through feasible region) (bottom). (D) HSPC subpopulation cell-count ratios between IκB− and WT. Each IκB− animal was compared with each WT animal resulting in 120 sets of data points. Gray lines connect cell-count ratios originating from a single IκB− and WT pair. (E) Scatterplot of 120 observations on feasibility map (left) with common rates across MPPs. Only 24 (gray) are feasible. Most have an increase in IκB− MPPs that exceeds what is permissible (red). Allowing for measurement error, a relative error rate of nearly 40% is needed to account for all data under the restricted model (right). (F) Scatterplot of 120 observations on feasibility map (left) with distinct rates across MPPs; 64 (gray) are feasible and a relative error rate near 27% is needed to account for all data (right). (G) Parameter fits to the average cell counts for a model where ST-HSC differentiation and branching ratio is allowed to vary between IκB− and WT, as well as the rate parameters for each MPP population. Formula for line of best fit specified for MPP parameters. (H) Top 10% of parameter fits in (G) ordered by smallest total difference (absolute value of the logarithm of ratios) between IκB− and WT parameters (p).

To evaluate whether HSC differentiation bias was sufficient to explain IκB− observations, we first identified sets of WT and IκB− counts (“feasible”) that conformed to a model where only ST-HSC differentiation rate and bias differed between conditions (Figure 1C; supplemental Information, Eq. 2.1-2.4). We found mean IκB− vs WT counts fell into the infeasible range, assuming a dynamically homogenous MPP compartment. Relaxing this assumption (supplemental Information, Eq. 2.7-2.10), the mean values were feasible; however, small measurement uncertainty could eliminate this possibility (Figure 1C). We therefore considered the variability in measured counts and paired measurements from each WT (n = 12) to IκB− animal (n = 10), yielding 120 count-ratio sets (Figure 1D). Only 20% of the observations could be explained by altering ST-HSC differentiation (Figure 1E), and a high relative-error rate (absolute difference of measured and true counts divided by true counts) of nearly 40% (typically <5% mean deviation for technical replicates) would be needed to capture all data (supplemental Information, Eq. 2.5-2.6). Dropping the homogenous MPP assumption still only explained 64 of 120 observations, with a relative error rate of nearly 30% needed to capture all data (Figure 1F), suggesting that ST-HSC differentiation bias is likely insufficient to explain IκB− HSPC counts.

To interrogate what additional rate alterations might promote myeloid bias, we next fit a model that also allowed MPP net proliferation and differentiation rates to vary between IκB− and WT (supplemental Information, Eq. 3.1-3.5). This model predicted increased ST-HSC differentiation rate (Figure1G; 2.12×, median [range, 1.02-2.24]), with changes in the branching ratio or dynamic rates specific to each MPP. Although the model permits different combinations of MPP changes, approximate ratios between model parameters are identifiable as the y-intercept of the best-fit line through predicted parameters (Figure 1G). The y-intercept values for MPP2 (1.90 [1.78, 2.59]) and MPP3 (1.03 [0.94, 1.75]) were positive and larger than for MPP4 (−0.14 [−0.22, 0.59]), indicating at least an increased branching ratio, decreased differentiation rate, or increased net proliferation rate for these IκB− subpopulations. Among the fits, we identified a subset that minimized the total difference between IκB− and WT parameters, suggesting the smallest changes that could generate the mutant counts. These mostly included decreased MPP4 branching ratio and favored MPP2 and MPP3 expansion, as evident by decreased differences between differentiation and net proliferation rates (Figure 1H). Together, these analyses suggest that MPP dynamic rate changes may underlie myeloid bias, in addition to ST-HSC differentiation bias.

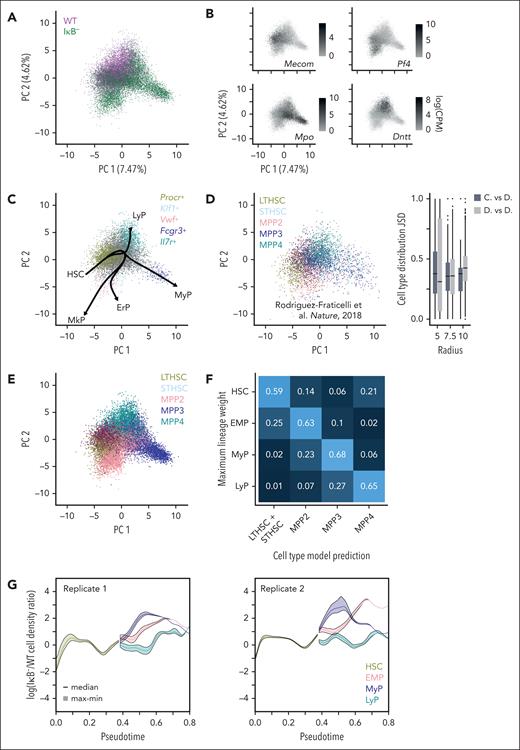

A cell-state coordinate system constructed from scRNA-seq measurements of HSPCs

For finer resolution of these additional dynamics responsible for the IκB− phenotype, we obtained scRNA-seq measurements of WT and IκB− HSPCs to provide a continuous analysis of cell states. These scRNA-seq data were projected into a low-dimensional space using 115 hematopoietic genes44-48 to focus on cell-cell differences meaningful to hematopoietic differentiation.49 Visualizing the first 2 principal components (Figure 2A) revealed clear differences in the IκB− and WT HSPC distributions. Marker-gene expression (Figure 2B) confirmed regions of increased IκB− density aligned with regions primed toward myeloid differentiation.

A cell-state coordinate system constructed from scRNA-seq measurements of HSPCs. (A) PCA of native HSPC scRNA-seq data with cells colored by genotype reveals differences in density across selected gene expression space. (B) PCA plots with cells colored by expression levels of different gene markers (Mecom, HSC; Pf4, megakaryocytes; Mpo, granulocytes; Dntt, lymphocytes). (C) Data (WT HSPCs) used for pseudotime analysis colored by input clusters defined by listed marker genes, with resulting differentiation trajectories given by black arrows. ErP, erythrocyte-primed; MkP, megakaryocyte-primed; MyP, myeloid-primed; LyP, lymphoid-primed. (D) Projection of published sorted HSPC scRNA-seq (inDrops platform) data50 into same PCA space (left). Jensen Shannon Divergence (JSD) values (right) between WT HSPC cell-identity distributions (lineage weights) and local distribution of cell types in sorted HSPCs within radius specified (dark gray). Most JSD values are closer to zero demonstrating similarity between the cell type and lineage-weight distributions. As a reference, the same computation was performed on the sorted HSPCs, using the sorted cell types as their cell-identity distributions (light gray). (E) PCA of native HSPC scRNA-seq data with cells colored by predicted cell type from classification model30 built from microarray data of sorted HSPCs.25 (F) Fraction of each cell type defined by maximum lineage-weight predicted as each cell type by classification model demonstrates strong correspondence (59%-68% match). (G) Logarithm of the ratio of IκB− to WT HSPC density over pseudotime for the different lineages in both experimental replicates. Densities were estimated 1000 times to reflect uncertainty in lineage assignments; solid line indicates median and shaded region covers minimum to maximum values.

A cell-state coordinate system constructed from scRNA-seq measurements of HSPCs. (A) PCA of native HSPC scRNA-seq data with cells colored by genotype reveals differences in density across selected gene expression space. (B) PCA plots with cells colored by expression levels of different gene markers (Mecom, HSC; Pf4, megakaryocytes; Mpo, granulocytes; Dntt, lymphocytes). (C) Data (WT HSPCs) used for pseudotime analysis colored by input clusters defined by listed marker genes, with resulting differentiation trajectories given by black arrows. ErP, erythrocyte-primed; MkP, megakaryocyte-primed; MyP, myeloid-primed; LyP, lymphoid-primed. (D) Projection of published sorted HSPC scRNA-seq (inDrops platform) data50 into same PCA space (left). Jensen Shannon Divergence (JSD) values (right) between WT HSPC cell-identity distributions (lineage weights) and local distribution of cell types in sorted HSPCs within radius specified (dark gray). Most JSD values are closer to zero demonstrating similarity between the cell type and lineage-weight distributions. As a reference, the same computation was performed on the sorted HSPCs, using the sorted cell types as their cell-identity distributions (light gray). (E) PCA of native HSPC scRNA-seq data with cells colored by predicted cell type from classification model30 built from microarray data of sorted HSPCs.25 (F) Fraction of each cell type defined by maximum lineage-weight predicted as each cell type by classification model demonstrates strong correspondence (59%-68% match). (G) Logarithm of the ratio of IκB− to WT HSPC density over pseudotime for the different lineages in both experimental replicates. Densities were estimated 1000 times to reflect uncertainty in lineage assignments; solid line indicates median and shaded region covers minimum to maximum values.

To describe the developmental pathway in a continuous manner,51,52 we defined differentiation trajectories using the pseudotime algorithm Slingshot,39 anchored by an HSC starting-cluster and erythrocyte-primed "ErP", megakaryocyte-primed "MkP" (∼MPP2), myeloid-primed "MyP" (∼MPP3), and lymphoid-primed "LyP" (∼MPP4) progenitor ending clusters defined by marker gene expression (Figure 2C). IκB− cells were projected onto the coordinate system constructed from WT data. We defined a branch-point where HSCs transition to progenitors at the pseudotime value where differentiation-trajectories diverged (supplemental Figure 1A). Pseudotimes before the branch-point were assigned to the HSC lineage and those beyond to the progenitors. The ErP and MkP lineages were collapsed into erythrocyte/megakaryocyte-primed "EMP" for simplification. The pseudotimes assigned to each cell provided a continuum description of cell states, and lineage weights provided assignment uncertainty (supplemental Figure 1B). These cell-state assignments were robust to choice of input cells (supplemental Figure 2)53 and algorithm (supplemental Figure 3A-B)54,55 used for pseudotime analysis, recapitulated expected lineage-associated expression patterns of hematopoietic transcription factors (TFs)56,57 (supplemental Figure 3C), and aligned with cell types defined by cell-surface markers (Figure 2D-F).50,58

Using these cell-state assignments, we quantified the continuous HSPC density along pseudotime (supplemental Figure 4). The ratio of IκB– vs WT density (Figure 2G) revealed a drop in HSC density just before the branch-point, and an increase in EMP and MyP progenitor densities, particularly early in the myeloid-primed progenitor lineage (more than 7× near pseudotime 0.5) in both replicates. This analysis of the scRNA-seq data provides greater dynamic detail than flow cytometry of the IκB− HSPC abundance changes.

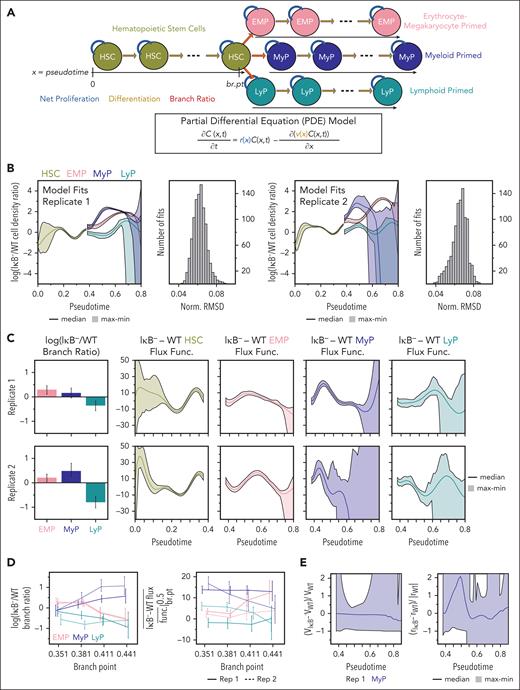

Early dynamic rate changes in myeloid-primed progenitors contribute to their expansion

We next updated our population dynamics model to capture the cell-state continuum. We described HSPC density over the HSC to progenitor differentiation axis using a reaction-advection model59,60 (Figure 3A; Eq. 2.1-2.3). The reaction and advection terms describe net proliferation and differentiation, respectively, and these rates vary along the differentiation trajectories. To identify likely dynamic parameter changes underlying the IκB− densities, we minimized the discrepancy between experimentally observed and model predicted densities (supplemental Information, Eq. 4.14). For each optimization run, the experimental densities were resampled to reflect cell-state assignment uncertainty. The model recapitulated the experimental data for both replicates, with a normalized root mean square deviation < 10% for all fits (Figure 3B). Toward the pseudotime extrema, the model was less constrained given the optimization objective and few cells captured.

Early dynamic rate changes in myeloid-primed progenitors contribute to their expansion. (A) Schematic of HSPC population dynamics model that uses PDEs to capture a continuum of cell-states along hematopoietic differentiation described by the pseudotime analysis. refers to the cell-density at pseudotime value at time . (B) Top model fits obtained for 1000 optimization runs of each replicate (each with a different estimate of the experimental cell densities). Normalized root mean square deviation (Norm. RMSD) was calculated by dividing each optimized objective value by the average experimental IκB− cell-density for that replicate. (C) Difference in branching ratio (left) and lineage developmental-flux functions (right) between IκB− and WT given by parameters underlying model fits. Error bars and shaded regions denote range. The branching ratio describes how much the HSCs contribute to each primed progenitor lineage at the branch-point. The developmental-flux function is composed of the net proliferation and differentiation rates, and its difference between IκB− and WT can be increased if IκB− net proliferation is increased or differentiation is decreased, and vice versa. (D) Difference in IκB− and WT branching ratio (left) and average difference in IκB− and WT developmental-flux functions over the domain from the branch-point to pseudotime value 0.5 (right) for model fits with different values for the branch-point. Lines connect median values and error bars denote maximum/minimum values across 500 fits. (E) Predicted difference between IκB− and WT differentiation (left) and net proliferation (right) rates relative to magnitude of WT rates from minimizing difference between IκB− and WT rates while satisfying the steady-state constraint of differences in developmental-flux functions. Results from replicate 1 where difference in flux functions determined with greater certainty.

Early dynamic rate changes in myeloid-primed progenitors contribute to their expansion. (A) Schematic of HSPC population dynamics model that uses PDEs to capture a continuum of cell-states along hematopoietic differentiation described by the pseudotime analysis. refers to the cell-density at pseudotime value at time . (B) Top model fits obtained for 1000 optimization runs of each replicate (each with a different estimate of the experimental cell densities). Normalized root mean square deviation (Norm. RMSD) was calculated by dividing each optimized objective value by the average experimental IκB− cell-density for that replicate. (C) Difference in branching ratio (left) and lineage developmental-flux functions (right) between IκB− and WT given by parameters underlying model fits. Error bars and shaded regions denote range. The branching ratio describes how much the HSCs contribute to each primed progenitor lineage at the branch-point. The developmental-flux function is composed of the net proliferation and differentiation rates, and its difference between IκB− and WT can be increased if IκB− net proliferation is increased or differentiation is decreased, and vice versa. (D) Difference in IκB− and WT branching ratio (left) and average difference in IκB− and WT developmental-flux functions over the domain from the branch-point to pseudotime value 0.5 (right) for model fits with different values for the branch-point. Lines connect median values and error bars denote maximum/minimum values across 500 fits. (E) Predicted difference between IκB− and WT differentiation (left) and net proliferation (right) rates relative to magnitude of WT rates from minimizing difference between IκB− and WT rates while satisfying the steady-state constraint of differences in developmental-flux functions. Results from replicate 1 where difference in flux functions determined with greater certainty.

Evaluating the parameter fits, we found decreased LyP branching-ratios in IκB− cells (0.61× [0.47-0.75], 0.43× [0.33-0.54]), that is, fewer HSCs differentiating into the lymphoid-primed lineage (Figure 3C). The other model parameters include the developmental-flux functions (supplemental Information, Eq. 4.8-4.13) which describe the rate of change in steady-state density across pseudotime. Inspecting differences between IκB− and WT developmental-flux functions, we observed the largest difference early on after the branch-point in the myeloid-primed lineage (+20.23 [17.64, 22.97], +23.59 [15.83, 32.69]; Figure 3C). To interrogate the robustness of the predictions, we repeated the analysis with reduced polynomial-order for the developmental-flux functions (supplemental Figure 5) and varied the branch-point (≈±10%, +20%; Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 6); all predicted reduced LyP branching-ratio and increased early MyP developmental-flux function in IκB−.

The increase in IκB− developmental-flux function may be attributed to increased net proliferation, decreased differentiation, or both. We leveraged published time course scRNA-seq measurements of labeled HSCs61 to probe these possibilities. We estimated WT dynamic parameters (supplemental Information, Eq. 5.1-5.4; supplemental Figure 7) that included rates across all of the differentiation trajectories and then determined IκB− rates that permitted the observed steady-state densities while minimizing the differences between IκB− and WT rates (supplemental Information, Eq. 5.5-5.6). The median predicted IκB− vs WT net proliferation was high in the MyP lineage (+2× near pseudotime 0.5), supporting increased net proliferation in the IκB− expansion of myeloid-primed progenitors (Figure 3E). However, model fits still include differences in IκB− and WT differentiation, so a role for altered differentiation cannot be eliminated.

Elevated NFκB activity in the niche is sufficient to dysregulate HSPC population dynamics

In IκB− mice, the observed HSPC phenotypes may be driven directly by increased NFκB activity within HSPCs or indirectly through an inflammatory microenvironment. Inflammatory cytokines were elevated in bone marrow supernatants from IκB− mice.30 Furthermore, experiments in which CD45.1 bone marrow was transplanted into WT vs IκB− CD45.2 recipients demonstrated that NFκB dysregulation in the niche was sufficient to drive phenotypic and transcriptomic myeloid bias of HSPCs30 (Figure 4A). We therefore asked whether inflammatory niche conditioning changed population dynamics as in IκB− HSPCs. Applying the same ODE model from Figure 1G (supplemental Information, Eq. 3.1-3.5) that permitted different ST-HSC differentiation and MPP-specific rates between IκB− and WT recipients, we found that mean cell counts could be explained by rate changes similar (but less severe) to those in native (nontransplanted) IκB− mice (Figure 4B). The model predicted increased ST-HSC differentiation in the IκB− recipient (1.24× [1.00-1.27]) and MPP-specific rate changes defined by their y-intercept values, again higher for MPP2 (0.08 [0.05, 0.29]) and MPP3 (0.45 [0.41, 0.65]) than for MPP4 (0.02 [−0.01, 0.23]).

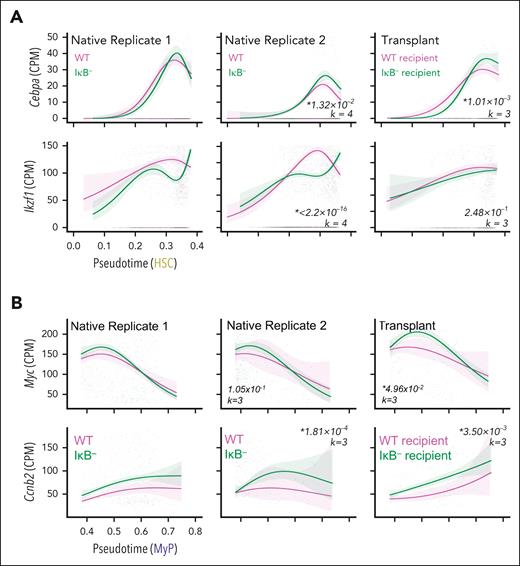

Elevated NFκB activity in the niche is sufficient to dysregulate HSPC population dynamics. (A) Average cell counts in HSPC subpopulations from WT donors transplanted into WT (n = 6) and IκB− (n = 4) recipients with individual data points overlaid. (B) ODE model parameter fits to average cell counts, in which differentiation rate and branching ratio for ST-HSCs and the rate parameters for each MPP population are allowed to vary between IκB− and WT recipients. Formula for line of best fit specified for MPP parameters. (C) Transplanted HSPC scRNA-seq data projected into same gene expression space as native HSPC PCA with cells colored by genotype of recipient. (D) Ratio of IκB− to WT recipient HSPC density over pseudotime (left) estimated 1000 times to reflect uncertainty in lineage assignments; solid line indicates median and shaded region covers minimum to maximum value. Top model fits (center) obtained for 1000 optimization runs of the PDE-based cell population dynamics model and respective normalized RMSD values (right). (E) Difference in branching-ratio (left) and lineage developmental-flux functions (right) between IκB− and WT recipient given by parameters underlying model fits. Error bars and shaded regions denote range. (F) Difference in branching ratio (left) and average difference of developmental-flux functions in early (br.pt to 0.5) progenitor lineages (right) for model fits with different values for the branch-point. Lines connect median values, and error bars denote maximum/minimum values across 500 fits.

Elevated NFκB activity in the niche is sufficient to dysregulate HSPC population dynamics. (A) Average cell counts in HSPC subpopulations from WT donors transplanted into WT (n = 6) and IκB− (n = 4) recipients with individual data points overlaid. (B) ODE model parameter fits to average cell counts, in which differentiation rate and branching ratio for ST-HSCs and the rate parameters for each MPP population are allowed to vary between IκB− and WT recipients. Formula for line of best fit specified for MPP parameters. (C) Transplanted HSPC scRNA-seq data projected into same gene expression space as native HSPC PCA with cells colored by genotype of recipient. (D) Ratio of IκB− to WT recipient HSPC density over pseudotime (left) estimated 1000 times to reflect uncertainty in lineage assignments; solid line indicates median and shaded region covers minimum to maximum value. Top model fits (center) obtained for 1000 optimization runs of the PDE-based cell population dynamics model and respective normalized RMSD values (right). (E) Difference in branching-ratio (left) and lineage developmental-flux functions (right) between IκB− and WT recipient given by parameters underlying model fits. Error bars and shaded regions denote range. (F) Difference in branching ratio (left) and average difference of developmental-flux functions in early (br.pt to 0.5) progenitor lineages (right) for model fits with different values for the branch-point. Lines connect median values, and error bars denote maximum/minimum values across 500 fits.

Transplanted WT HSPCs from WT or IκB− recipients were also analyzed by scRNA-seq30 (Figure 4C). Projecting these data into the same gene expression space as the native data, we observed increased IκB− recipient density among myeloid-primed progenitors (Figure 4D). Inspecting the PDE model fits of the HSPC densities, we found decreased LyP branching ratio (0.70 × [0.52-0.90]) and increased early MyP developmental-flux function (+18.69 [13.88-23.52]) in the IκB− recipient (Figure 4E), and varying the branch-point demonstrated robustness of these predictions (Figure 4F). These findings suggest that cell-extrinsic NFκB activity is sufficient to dysregulate both HSC differentiation and MyP expansion.

Differential gene expression along lineages supports mathematical model predictions

We next analyzed differential expression along pseudotime of genes with known function to evaluate our mathematical model predictions. We developed LineageDE to test for statistically significant differences between experimental conditions. We first applied LineageDE to evaluate lineage-associated TFs along the HSC lineage (Figure 5A). Cebpa (important for myelopoiesis62,63 and suppressing lymphoid development64) expression increased with HSC differentiation and reached a higher peak in IκB− conditions, whereas Ikzf1 (important for lymphopoiesis65) expression also increased along the HSC lineage but was reduced in late IκB− HSCs. These gene expression differences support reduced HSC contribution to the LyP lineage, aligning with the predicted decrease in lymphoid-lineage branching ratio.

Differential gene expression along lineages supports mathematical model predictions. (A) Expression of Cebpa and Ikzf1 along the HSC lineage, transcription factors important for myeloid and lymphoid development, respectively. (B) Expression of Myc and cell-cycle gene, Ccnb2, along the MyP lineage, associated with cell proliferation. Lines in A and B are NB-GAM fits, shaded regions are 95% confidence intervals, and transparent points are individual cell data. Italicized numbers are P values and degrees of freedom used for NB-GAM fits specified by k.

Differential gene expression along lineages supports mathematical model predictions. (A) Expression of Cebpa and Ikzf1 along the HSC lineage, transcription factors important for myeloid and lymphoid development, respectively. (B) Expression of Myc and cell-cycle gene, Ccnb2, along the MyP lineage, associated with cell proliferation. Lines in A and B are NB-GAM fits, shaded regions are 95% confidence intervals, and transparent points are individual cell data. Italicized numbers are P values and degrees of freedom used for NB-GAM fits specified by k.

Furthermore, PDE modeling predicted an increase in the early MyP developmental-flux function for IκB− HSPCs. One potential explanation for this difference is a higher proliferation rate in these cells; thus, we evaluated the expression of genes important for cell growth and division. Myc and Ccnb2 expression were increased in cells from IκB− models early in the MyP lineage compared with WT models (Figure 5B). The difference in Myc expression is statistically significant in the transplant data set but falls short in the native (P value = 1.05 × 10−1); however, c-Myc response genes Cdk4 and Ccnb166 were elevated in cells from both native and recipient IκB− (supplemental Figure 8A). The early increase in Myc expression was also unique to the MyP lineage (supplemental Figure 8B), as Myc expression revealed a modest, late increase in the EMP lineage and was decreased or unchanged in the LyP lineage. These gene expression differences support increased proliferation in myeloid-primed progenitors as important for myeloid bias.

Aged murine HSPCs show evidence of myeloid-primed progenitor expansion

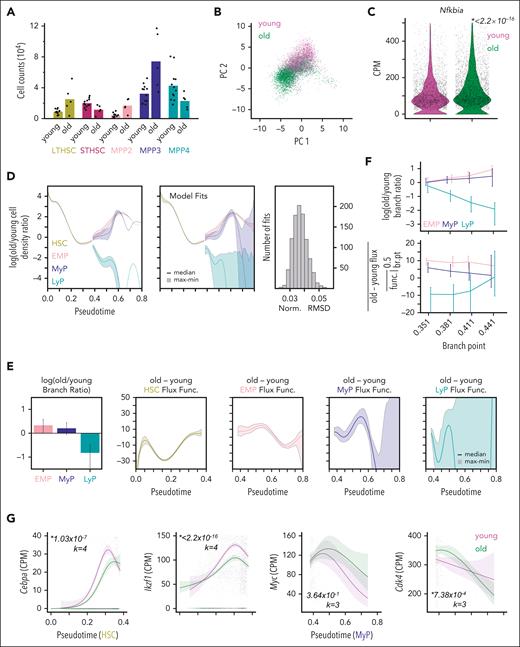

As aging is associated with myeloid bias and elevated NFκB activity,31,32 we asked whether the rate changes found in the IκB− mouse models also occur with aging. Evaluating HSPC counts from young (8-12 weeks) and old (18-22 months) mice,30 we observed more MPP2s and MPP3s as in native IκB− and a decrease in ST-HSCs (Figure 6A). Aged bone marrow also revealed an increase in long-term HSCs in line with established literature,67 but unlike IκB− models; thus, we asked whether altered short-term HSC differentiation could sufficiently account for the age-related increase in MPPs. Evaluating all old to young cell-count ratios, 58 of 60 observations could potentially be explained by a model with only ST-HSC differentiation altered with aging (supplemental Information, Eq. 2.7-2.10). However, given the NFκB dysregulation associated with aging, we wondered whether additional dynamics changes found in the IκB− mouse models remained a possibility.

Aged murine HSPCs show evidence of myeloid-primed progenitor expansion. (A) Average cell counts in HSPC subpopulations from young (n = 12) and old (n = 5) mice with individual data points overlaid. (B) HSPC scRNA-seq data from young and old mice projected into same gene expression space as native HSPC PCA with cells colored by age. (C) Expression of Nfkbia in old vs young HSPCs. Italicized number is P value given by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (D) Ratio of old to young HSPC density over pseudotime (left) estimated 1000 times to reflect uncertainty in lineage assignments; solid line indicates median and shaded region covers minimum to maximum value. Top model fits (center) obtained for 1000 optimization runs of the PDE-based cell population dynamics model and respective normalized RMSD values (right). (E) Difference in branching ratio (left) and lineage developmental-flux functions (right) between old and young mice given by parameters underlying model fits. Error bars and shaded regions denote range. (F) Difference in branching ratio (top) and average difference of developmental-flux functions in early (branch-point to 0.5) progenitor lineages (bottom) for model fits with different values of the branch-point. Lines connect median values and error bars denote maximum/minimum values across 500 fits. (G) Expression of Cebpa and Ikzf1 along the HSC lineage (left) and expression of Myc and c-Myc response gene, Cdk4, along the MyP lineage (right) in old vs young HSPCs. Lines in G are NB-GAM fits, shaded regions are 95% confidence intervals, and transparent points are individual cell data. Italicized numbers are P values and degrees of freedom used for NB-GAM fits specified by k.

Aged murine HSPCs show evidence of myeloid-primed progenitor expansion. (A) Average cell counts in HSPC subpopulations from young (n = 12) and old (n = 5) mice with individual data points overlaid. (B) HSPC scRNA-seq data from young and old mice projected into same gene expression space as native HSPC PCA with cells colored by age. (C) Expression of Nfkbia in old vs young HSPCs. Italicized number is P value given by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (D) Ratio of old to young HSPC density over pseudotime (left) estimated 1000 times to reflect uncertainty in lineage assignments; solid line indicates median and shaded region covers minimum to maximum value. Top model fits (center) obtained for 1000 optimization runs of the PDE-based cell population dynamics model and respective normalized RMSD values (right). (E) Difference in branching ratio (left) and lineage developmental-flux functions (right) between old and young mice given by parameters underlying model fits. Error bars and shaded regions denote range. (F) Difference in branching ratio (top) and average difference of developmental-flux functions in early (branch-point to 0.5) progenitor lineages (bottom) for model fits with different values of the branch-point. Lines connect median values and error bars denote maximum/minimum values across 500 fits. (G) Expression of Cebpa and Ikzf1 along the HSC lineage (left) and expression of Myc and c-Myc response gene, Cdk4, along the MyP lineage (right) in old vs young HSPCs. Lines in G are NB-GAM fits, shaded regions are 95% confidence intervals, and transparent points are individual cell data. Italicized numbers are P values and degrees of freedom used for NB-GAM fits specified by k.

To address this, we fit our continuous cell-state model to published scRNA-seq data of HSPCs from young (6-12 weeks) and old (18-31 months) mice.68 Aged HSPCs had diminished abundance in the high lymphoid-marker PCA region (Figure 6B) and elevated NFκB-response gene expression, Nfkbia (Figure 6C), consistent with previous findings of elevated NFκB activity.30,31 Mapping these data onto the cell-state axis revealed an increase in the EMP and MyP lineage of aged HSPCs and a significant drop in the LyP lineage (Figure 6D). Fitting these data with our PDE model revealed perturbations in dynamic parameters of aged HSPCs such as those found in IκB− data: decreased LyP branching ratio (0.44× [0.24-0.61]) and increased MyP developmental-flux function (+25.42 [16.57-36.06]; Figure 6E). Again, varying the branch-point demonstrated robustness in these predictions (Figure 6F). Although Cebpa expression was not elevated in aged HSPCs along the HSC lineage, Ikzf1 was decreased in aged HSCs consistent with the decreased LyP branching ratio (Figure 6G). Along the MyP lineage, Myc-responsive gene Cdk4 was significantly increased in early MyP cells (Figure 6G), consistent with the increased MyP developmental-flux function with aging.

Model-aided analysis identifies common HSPC dysregulation in myeloid neoplasms

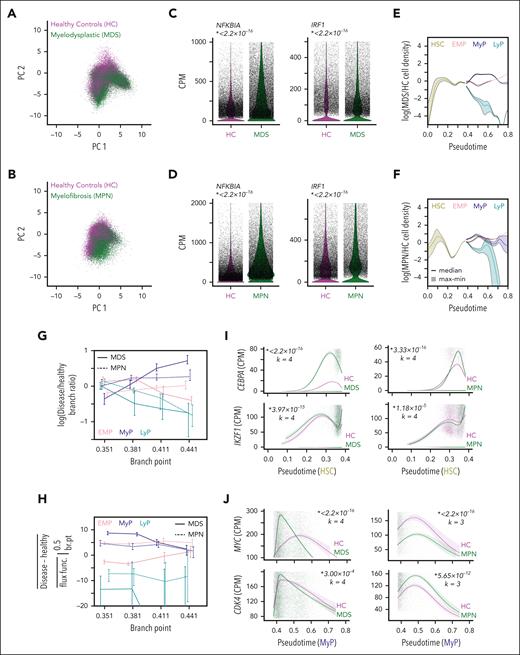

We explored the applicability of our population dynamics analysis to published scRNA-seq data of HSPCs from patients with myeloid neoplasms. Although myelodysplastic neoplasm (MDS) is characterized by cytopenias and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) instead display overabundant hematopoietic output, NFκB dysregulation is common between them,34,35,69-71 and suggested as a therapeutic target in both.72,73 Several NFκB-signaling pathway components can be overexpressed or have gain-of-function mutations in MDS,74 including toll-like receptors,75-77 MYD88,78 and IRAK1.79 Here, we evaluated CD34+ HSPCs from the bone marrow of 4 patients with MDS (aged 54-83 years; WHO fourth edition classification MDS with multineage dysplasia) and 3 healthy controls (61-74 years).80 NFκB activation in MPNs may result directly from activated kinase signaling or through increased inflammatory mediator expression.81,82 We also evaluated CD34+ HSPCs collected from the peripheral blood of patients with myelofibrosis,83 from which we analyzed data from 5 patients with exclusively JAK2V617F mutations (49-79 years) and 6 healthy controls (51-67 years).

When projected into the previously defined PCA coordinates (mapping mouse genes to human orthologs), the MDS and MPN HSPC distributions were elevated in high myeloid-marker regions (Figure 7A-B), and NFκB-response gene expression, NFKBIA and IRF1, were elevated (Figure 7C-D). We calculated the patient vs control HSPC ratio along pseudotime (Figure 7E-F). As total HSPC abundance information is not available for these data sets, we assumed equal numbers across conditions. This assumption may vertically shift the entire plot, but importantly, the curves’ shapes are unaffected. HSPC cell abundance ratios for both patients with MDS and patients with MPN increased in the MyP lineage relative to that in HSC lineage at the branch-point, whereas it decreased in the LyP lineage.

Model-aided analysis identifies common HSPC dysregulation in myeloid neoplasms. (A) CD34+ HSPC scRNA-seq data from patients with MDS and healthy controls (HC) (B: patients with MPN and HC) projected into the same gene expression space as the murine models. (C) Expression of NFκB-response genes, Nfkbia and Irf1, in MDS vs HC HSPCs (D: MPN vs HC HSPCs). Italicized number is P value given by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (E) Ratio of MDS to HC HSPC density (F: MPN to HC HSPC density) over pseudotime (assuming equal number of HSPCs in each condition) estimated 1000 times to reflect uncertainty in lineage assignments; solid line indicates median and shaded region covers minimum to maximum value. (G) Difference in branching ratio between MDS (solid lines) or MPN (dashed lines) and HC inferred from fitting the population dynamics model to the scRNA-seq data with different branch-point values. Lines connect median values and error bars denote maximum/minimum values across 500 fits. (H) Analogous to G for the average difference of developmental-flux functions in early (branch-point to 0.5) progenitor lineages. (I) Expression of Cebpa and Ikzf1 along the HSC lineage in MDS patients (left) and MPN patients (right) compared with healthy controls. (J) Expression of Myc and c-Myc response gene, Cdk4, along the MyP lineage in patients with MDS (left) and patients with MPN (right) compared with healthy controls. Lines in panels I-J are NB-GAM fits, shaded regions are 95% confidence intervals, and transparent points are individual cell data. Italicized numbers are P values and degrees of freedom used for NB-GAM fits specified by k.

Model-aided analysis identifies common HSPC dysregulation in myeloid neoplasms. (A) CD34+ HSPC scRNA-seq data from patients with MDS and healthy controls (HC) (B: patients with MPN and HC) projected into the same gene expression space as the murine models. (C) Expression of NFκB-response genes, Nfkbia and Irf1, in MDS vs HC HSPCs (D: MPN vs HC HSPCs). Italicized number is P value given by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (E) Ratio of MDS to HC HSPC density (F: MPN to HC HSPC density) over pseudotime (assuming equal number of HSPCs in each condition) estimated 1000 times to reflect uncertainty in lineage assignments; solid line indicates median and shaded region covers minimum to maximum value. (G) Difference in branching ratio between MDS (solid lines) or MPN (dashed lines) and HC inferred from fitting the population dynamics model to the scRNA-seq data with different branch-point values. Lines connect median values and error bars denote maximum/minimum values across 500 fits. (H) Analogous to G for the average difference of developmental-flux functions in early (branch-point to 0.5) progenitor lineages. (I) Expression of Cebpa and Ikzf1 along the HSC lineage in MDS patients (left) and MPN patients (right) compared with healthy controls. (J) Expression of Myc and c-Myc response gene, Cdk4, along the MyP lineage in patients with MDS (left) and patients with MPN (right) compared with healthy controls. Lines in panels I-J are NB-GAM fits, shaded regions are 95% confidence intervals, and transparent points are individual cell data. Italicized numbers are P values and degrees of freedom used for NB-GAM fits specified by k.

We then fit the PDE model to these data (supplemental Figure 9A-B) and found dynamic parameter changes (decreased LyP branching ratio and increased early MyP developmental-flux function) in both myeloid neoplasms as observed in the IκB− models (supplemental Figure 9C-D). Varying the branch-point, these model predictions were robust, especially the increased early MyP developmental-flux (Figure 7G-H). Lineage-associated TF expression mirrored our branching-ratio findings, with increased CEBPA in the MDS and MPN HSC lineages, and reduced IKZF1 just before the branch-point in the MPN HSC (Figure 7I). Evaluating the MyP lineage, MYC and CDK4 expression were elevated early in MDS cells (Figure 7J). In patients with MPN, CDK4 expression was increased, though surprisingly, MYC expression was decreased (Figure 7J), perhaps reflecting G-CSF exposure in healthy controls for peripheral mobilization which is known to induce MYC.84 Evaluation of additional proliferative markers85 supported increased proliferation underlying myeloid-primed progenitor expansion in patients with MDS and patients with MPN (supplemental Figure 9E).

Discussion

Previous work established that myeloid bias is rooted in early hematopoiesis; however, the population dynamics changes that contribute to this phenotype had not been quantified. Here, we studied HSPC changes caused by chronic inflammation by developing a mathematical modeling approach that allowed us to quantify differences in differentiation and net proliferation rates. We then applied this modeling framework to published data sets of HSPCs from aged mice and human patients with myeloid neoplasm, revealing common population dynamics mechanisms underlying myeloid bias across these conditions.

Comparing HSPC counts from NFκB-dysregulated IκB− mutants with WT controls revealed that ST-HSC differentiation bias is likely insufficient to explain increases in MPP3s. Evaluating scRNA-seq measurements of these HSPCs and positioning cells along a continuous cell-state axis, we found that early expansion of myeloid-primed progenitors also contributes to myeloid bias in addition to loss of lymphoid-fate specification in HSCs. Differential gene expression supported increased proliferation among myeloid-primed progenitors early in the lineage. Transplanting WT HSPCs into IκB− recipients demonstrated that an inflammatory niche was sufficient to induce both HSC and MyP changes in population dynamic rates. Key to these analyses was the quantification of HSPC dynamic rates, which requires interpretation of cell abundances with a population dynamics model. These estimates considered uncertainty in experimental observations, such as cell counting error in flow cytometry, or lineage assignment ambiguity in pseudotime analysis.

Steady-state measurements of HSPCs specified relationships between dynamic rates, and we leveraged gene expression data to refine predictions, leveraging mechanistic-modeling and data-driven approaches together.86 Several studies have attempted to infer dynamic rates from scRNA-seq data sets, but with additional data or assumptions. Fischer et al60 inferred rates for T-cell maturation but with scRNA-seq data sets at 8 time points during embryogenesis. Even if multiple scRNA-seq experiments can be performed, many dynamic processes are at steady state and require labeling to generate time course data.87 Weinreb et al59 determined the differentiation potential of WT HSPCs from steady-state scRNA-seq data by assuming cell entry/exit rates from previous literature; however, these rates may not hold across mutant-model or disease contexts. Other methods use RNA velocity to characterize differentiation. Those based on quantification of unspliced vs spliced transcripts often require strong modeling assumptions,88,89 whereas others based on time-resolved scRNA-seq require additional metabolic labeling.90 Here, we have demonstrated that information about dynamic rate changes can be learned from single-snapshot, steady-state scRNA-seq data sets, which is obtainable for human patients.

For our population dynamics analyses, we assumed a simple model topology of early hematopoiesis. Previous scRNA-seq studies have suggested additional or alternative differentiation paths50,91 and unipotent progenitors among HSPCs.47,92 However, the true in vivo differentiation potential of HSPCs at single-cell resolution remains unresolved, and a lack of consistent cell-identity definitions makes integration of findings challenging. Model topology could also change in mutant-model or disease contexts. Previous work has suggested potential transdifferentiation of B-cell progenitors to myeloid progenitors93; however, it is unclear from where these myeloid-like cells specifically originate. Although this possibility, which might be variable across settings of myeloid bias, cannot be ruled out by our analysis, we are still able to rule in other dynamic rate changes. We also defined cell states in our model from gene expression data, but fate-commitment markers could be better correlated with epigenetic changes, posttranslational modifications, etc. Although our chosen model topology may have combined or omitted some differentiation branches, it nonetheless permitted sufficient parameter identifiability to detect biological differences across murine models, aging, and myeloid neoplasm conditions, all supported by the expression of hallmark genes Cebpa, Myc, or Cdk4.

In all settings of myeloid bias we explored, both HSC differentiation bias and myeloid-primed progenitor expansion contributed. However, these may not be driven by the same mechanisms or be equally responsive to the same driver. As myeloid progenitor expansion is downstream of HSC fate commitment, effectively limiting this expansion could adequately control myeloid bias in early hematopoiesis. Furthermore, our analysis suggests that an inflamed niche is sufficient to drive myeloid bias with progenitor proliferation. Cell-extrinsic factors are more pharmacologically targetable and proinflammatory cytokine blockade could limit myeloid expansion.94 Combining HSPC abundance data with our model-aided analysis, rate changes in patients may be quantifiable and inform the utility of targeting myeloid progenitor expansion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yu-Sheng Lin for initiating the project; Yi Liu and Kylie Farrell for technical assistance; and Haripriya Vaidehi Narayanan for feedback on the manuscript. The visual abstract was generated using components from Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

A.S. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences training grants T32GM008185 and T32GM008042. J.J.C. acknowledges support from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine UCLA Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research Training Program. This research was funded by the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R01AI127867, R01AI173214, and R01AI132731 (A.H.) and the NIH, National Cancer Institute grant R01CA264986 (D.S.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.S. developed the methodology, analyzed the data, and generated the figures; J.J.C. designed and performed the experiments; A.S. and A.H. wrote the manuscript; J.J.C. and D.S.R. edited the manuscript; D.S.R. supervised the bone marrow transplantation experiments; and A.H. oversaw work and provided funding.

Conflict of interest disclosure: D.S.R. has served as a consultant to AbbVie, a pharmaceutical company that develops and markets drugs for hematologic disorders. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alexander Hoffmann, UCLA MIMG Box 951570, 570 Boyer Hall, Los Angeles, CA 90095; email: ahoffmann@ucla.edu.

References

Author notes

The single-cell RNA-sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE262024).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal