In this issue of Blood, Kauppi et al show evidence that cullin 5 (Cul5) functions as a negative regulator of megakaryocyte (Mk)–biased progenitors within the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) pool.1 These data suggest Cul5 may be a critical player in the production of platelets in response to acute need, thus having implications for inflammation and disease.

A series of lineage-specific differentiation pathways can facilitate rapid production of blood cells from HSCs in response to acute need.2-4 This includes a subset of Mk-biased stem-like progenitor cells (Mk-SLPs) within the lineage –Sca-1+c-Kit+CD48–CD150+ (SLAM) HSC fraction that express Mk lineage determinants, including CD41 and von Willebrand factor (VWF).5 This population rapidly expands to generate Mk upon challenge with proinflammatory factors, including interferons (IFNs) and interleukin-1 (IL-1), and has increased abundance in the context of aging.5-7 However, the molecular mechanisms that regulate this unique pool of lineage-primed cells are incompletely understood.

Here, the authors explore the importance of Cul5 in hematopoiesis. Cul5 serves as a scaffold that coordinates assembly of cullin-RING-E3 ubiquitin ligase (CRL) complexes, which ubiquitinate protein targets for degradation.8 Importantly, CRL complexes incorporate proteins with suppressor of cytokine signaling box domains that target numerous proteins involved in JAK-STAT signaling.8 This includes cytokines that trigger inflammation and/or direct blood cell development, including IFNs, thrombopoietin (TPO), and IL-3. Strikingly, the authors show that deletion of Cul5 murine in hematopoietic cells using a Vav-Cre driver leads to an overabundance of platelets in the blood, accompanied by expansion of Mk and CD41+/VWF+ populations and clonogenic activity in the SLAM HSC fraction. Importantly, this phenotype was not replicated using the Mk lineage-specific Pf4-Cre driver, indicating Cul5 is required to regulate Mk production directly from HSCs vs downstream lineage-committed progenitors that express Pf4. Likewise, single-cell RNA sequencing and proteomics analysis validated the expansion of SLAM cells that exhibit features of Mk-SLPs, based on the expression of gene expression and proteomic signatures identified by previous studies.5 Taken together, the authors show that Cul5 plays a crucial role in regulating the size of the Mk-SLP pool, and in its absence Mk generation from the HSC compartment is substantially enhanced (see figure). Although Cul5-deficient mice exhibit thrombocytosis, addressing whether loss of Cul5 impacts the functional properties of Mk and platelets remains an important next step, with implications for aging, immune function, and cardiovascular disease. Lastly, the authors found that the abundance of other blood lineages or their progenitors was not significantly impacted by loss of Cul5, even though Cul5 could presumably regulate signaling from other hematopoietic cytokines using JAK-STAT, such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor or IL-3.

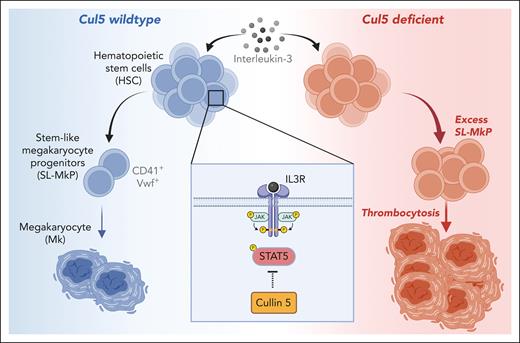

The role of Cul5 in megakaryopoiesis. HSCs are capable of rapidly differentiating into Mk via a subset of CD41+ VWF+ HSC-like cells termed stemlike megakaryocyte progenitors (SL-MkPs). SL-MkPs, in turn, differentiate into Mk. This pathway serves as a demand-adapted mechanism for rapid platelet production in response to inflammation and other cues. Cul5, which serves as a scaffold for CRL complexes, regulates this process via suppression of IL-3–mediated activation of STAT5. In its absence, IL-3 signaling triggers excess expansion of SL-MkPs and subsequent thrombocytosis. IL-3R, IL-3 receptor. Figure created with BioRender.com.

The role of Cul5 in megakaryopoiesis. HSCs are capable of rapidly differentiating into Mk via a subset of CD41+ VWF+ HSC-like cells termed stemlike megakaryocyte progenitors (SL-MkPs). SL-MkPs, in turn, differentiate into Mk. This pathway serves as a demand-adapted mechanism for rapid platelet production in response to inflammation and other cues. Cul5, which serves as a scaffold for CRL complexes, regulates this process via suppression of IL-3–mediated activation of STAT5. In its absence, IL-3 signaling triggers excess expansion of SL-MkPs and subsequent thrombocytosis. IL-3R, IL-3 receptor. Figure created with BioRender.com.

These results beg the question as to what cytokine pathways are deregulated by loss of Cul5. Interestingly, the authors’ proteomics analysis of lineage –Sca-1+c-Kit+ LSK cells from Cul5-deficient mice uncovered an upregulation of IFN response genes relative to wild-type controls. Whether this proteomic signature is related to the increased relative abundance of Mk-SLPs within the LSK fraction vs increased IFN activity attributable to Cul5 deletion is not clear. However, compound deletion of Ifnar1 or use of a Socs1 loss-of function mutation did not rescue the phenotype of Cul5-deficient mice, suggesting homeostatic type 1 IFN signaling is unlikely to play a role. Likewise, despite the important role for TPO in Mk development, deletion of Thpo or Mpl (the TPO receptor) did not rescue the relative overabundance of stemlike MK progenitors (SL-MkPs) or downstream Mk and platelets. Instead, absolute numbers of these cells were reduced across the board, consistent with previous characterizations of the knockouts.9 However, the authors found that knockout of the β common chain receptor, coupled with knockout of the mouse IL-3 β chain, ameliorated excessive thrombopoiesis in Cul5-deficient mice. The authors further identified IL-3, which has been shown to promote Mk differentiation,10 as the most likely driver of excessive thrombopoiesis in the Cul5-deficient setting via in vitro growth and clonogenic assays (see figure). Mechanistically, the authors found increased STAT5 phosphorylation in Cul5-deficient LSK cells treated with IL-3, suggesting the JAK2/STAT5 axis is likely to be the regulatory target of Cul5 in HSCs.

Collectively, the authors have identified a unique role for Cul5 as a regulator of HSC-directed Mk production, via suppression of IL-3 signaling. Further proteomics and mechanistic investigations will be needed to identify the direct target(s) of the Cul5 CRL complex that regulate megakaryopoiesis via the SL-MkP pathway. Furthermore, whether increases in the activity of STAT5 or other factor(s) are directly responsible for increased SL-MkP megakarypoiesis in Cul5-deficient mice is an open question with potentially important therapeutic implications.

This study raises numerous questions relating to the molecular and signaling requirements for homeostatic vs acute demand-adapted differentiation pathways in the hematopoietic system. Although proinflammatory factors drive expansion of Mk-SLPs, this study calls into question whether such signals are sufficient to activate demand-adapted megakaryopoiesis, which may instead rely on changes in IL-3 production and/or signaling activity triggered by inflammatory signals. Further experiments should address whether Cul5 is in fact a relevant regulator of demand-adapted megakaryocyte production using inflammatory challenge models in the Cul5-deficient setting. Likewise, whether inflammatory challenge, aging, and/or myeloproliferative mutations in JAK kinases suppress Cul5 expression and/or activity to drive increased Mk production, or simply trigger sufficient JAK/STAT signaling to overcome Cul5 regulation, remains to be determined. Last, the lineage-specific impact of Cul5 deletion suggests that other mechanism(s) regulating protein ubiquitination and degradation could have similar roles regulating demand-adapted hematopoiesis in other lineages. Numerous protein ubiqiutinase complexes have been already shown to play important roles in regulating HSC function. Further investigation will be needed to address the relevance of these mechanisms in demand-adapted production of other blood cell lineages from HSCs, such as the multipotent progenitor 3/multipotent progenitor granulocyte-macrophage pathway for myeloid cell production.2,4 Altogether, this study refines our understanding of the mechanisms regulating megakaryocyte production and offers new lines of investigation to address implications of these findings for aging and disease.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal