In this issue of Blood, Efficace and colleagues presented secondary end point results of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) from a phase 3 randomized acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) trial of 606 patients.1 Fit adults aged 60+ were randomized to decitabine (10 days) or daunorubicin + cytarabine (3 + 7) with the intent to transplant. HRQoL was measured with the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 302 and the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire Elderly 14.3 Data were collected at baseline, at recovery from cycle 2, at 6 months, at 12 months after randomization, and before and 100 days after transplantation.

The study design is robust, comparing 2 treatments in a randomized controlled trial, and provides estimates for both survival and HRQoL, showing that the risk of deterioration in HRQoL in the decitabine arm was lower compared with the 3 + 7 arm at the 2-month recovery time point (see figure). Survival and allogeneic stem cell transplant rates were similar between the 3 + 7 and decitabine treatment groups. No significant differences were detected in HRQoL at long-term follow-up after the results were merged for 6 and 12 months. Deteriorations in HRQoL were identified between baseline and postallogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for both groups. Physical and role functioning (the capacity of an individual to perform activities typical to a specific age and particular social responsibility), fatigue, pain, and burden of illness were chosen as end points before the study commenced. Patients in the 3 + 7 arm had clinically meaningful deteriorations in 4 of the 5 subscales for HRQoL, and those in the decitabine arm did not.

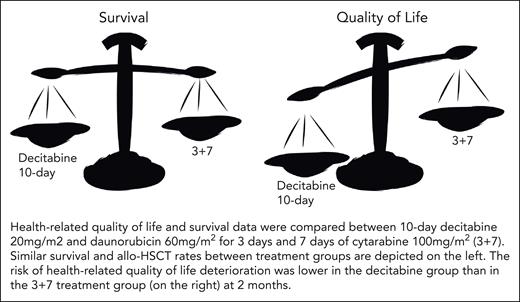

HRQoL and survival data were compared between 10-day decitabine 20 mg/m2 and daunorubicin 60 mg/m2 for 3 days and 7 days of cytarabine 100 mg/m2 (3 + 7). Similar survival and allo-HSCT rates between treatment groups are depicted on the left. The risk of HRQoL deterioration was lower in the decitabine group than in the 3 + 7 treatment group (on the right) at 2 months.

HRQoL and survival data were compared between 10-day decitabine 20 mg/m2 and daunorubicin 60 mg/m2 for 3 days and 7 days of cytarabine 100 mg/m2 (3 + 7). Similar survival and allo-HSCT rates between treatment groups are depicted on the left. The risk of HRQoL deterioration was lower in the decitabine group than in the 3 + 7 treatment group (on the right) at 2 months.

Both HRQoL and survival data are important when discussing treatment options. If survival is similar between treatments, HRQoL may be the tiebreaker. Overall survival has typically been the benchmark for success in oncology clinical trial end points.4 Improvement in HRQoL is prioritized over survival by many patients with cancer, especially older adults.5 This is one of the few well-designed studies with compelling data on survival and HRQoL from 606 participants. These findings provide evidence for a more balanced discussion between the health care team, patient, and caregiver for shared decision-making that includes patient goals.

Recommendations for treatment of older adults with AML are particularly complex and challenging.6 This is due to frailty, performance status, and comorbidity heterogeneity among older adults. A personalized approach for each patient will help identify the best treatment that will do more good than harm. One of the challenges in engaging older patients in evidence-based discussions is the need for more data on older adults with AML in an era of expanding treatment options. Eleven new treatments have been approved for the treatment of AML since 2017, including those specifically designed for older adults with AML.7 The Food and Drug Administration approval of these new treatments has been based on survival, with inadequate data on HRQoL, frailty, performance status, and comorbidities.

A multidisciplinary committee from the American Society of Hematology (ASH) developed guidelines for treating newly diagnosed older adults with AML.8 The ASH 2020 guidelines are evidence-based recommendations. The McMaster Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Centre assisted in developing the guidelines by performing systematic reviews and leading the GRADE approach. Recommendations made in the guidelines are for the treatment of older adults with AML over no treatment. If a patient is deemed fit enough for intensive therapy, this treatment is recommended over less intensive therapy. Importantly, these guidelines emphasize continuing conversations between clinicians and patients, focused on treatment goals and discussion of the risks and benefits of treatments. Few published studies have patient-reported outcomes with AML treatment, which is a limitation of the guidelines. These recommendations underscore the need for greater diligence in patient-reported outcomes and evaluation of quality of life to inform and ensure the highest-quality shared decision-making between clinicians and patients and caregivers.

This study by the Gruppo Italiano Malattie EMatologiche dell'Adulto (GIMEMA) and German Myelodysplastic Syndromes Study Group (GMDS-SG) group contributes to an area of great need in creating evidence-based guidelines. This will enhance the discussion of risks and benefits between treatments. Future studies can be strengthened by including assessments of frailty, comorbidity, and patient goals and preferences. This work is a template for incorporating HRQoL and survival to provide a more comprehensive comparison between treatments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal