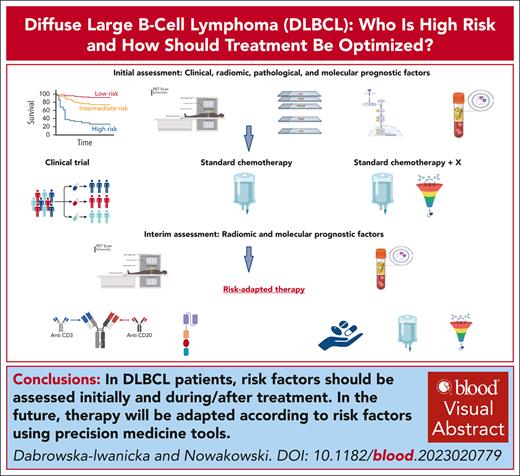

Visual Abstract

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), not otherwise specified, is the most common subtype of large B-cell lymphoma, with differences in prognosis reflecting heterogeneity in the pathological, molecular, and clinical features. Current treatment standard is based on multiagent chemotherapy, including anthracycline and monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, which leads to cure in 60% of patients. Recent years have brought new insights into lymphoma biology and have helped refine the risk groups. The results of these studies inspired the design of new clinical trials with targeted therapies and response-adapted strategies and allowed to identify groups of patients potentially benefiting from new agents. This review summarizes recent progress in identifying high-risk patients with DLBCL using clinical and biological prognostic factors assessed at diagnosis and during treatment in the front-line setting, as well as new treatment strategies with the application of targeted agents and immunotherapy, including response-adapted strategies.

Introduction

Large B-cell lymphomas (LBCLs) account for ∼30% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (DLBLC NOS) being the most common subtype.1 Immunochemotherapy with R-CHOP containing anti-CD20 antibody, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and steroids has been the mainstay of DLBCL treatment for the last 20 years, resulting in a long-time overall survival (OS) of ∼60%.2

Unfortunately, patients with early relapse or refractory disease have a dismal prognosis, with a median OS of 6.3 months and 3-year event-free survival (EFS) of only 20% in relapsed patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT).3,4 Recently, the survival of patients with relapsed and refractory DLBCL has improved owing to the introduction of immunotherapy, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy.5-9 However, even with these approaches, most patients succumb to disease. Numerous efforts have been made to identify patients at high risk of disease relapse based on clinical, pathological/molecular factors, early response to therapy, and to optimize their treatment in the front-line setting. Although these are yet to be translated into new treatment paradigms, they are used for the design of new clinical trials that will likely impact new therapeutic strategies.

This review focused primarily on defining high-risk patients with DLBCL NOS and other aggressive subtypes of LBCLs, such as high-grade B-cell lymphomas and approaches to improve their outcomes.

Clinical prognostic factors

The International Prognostic Index (IPI), which is based on clinical factors, was developed in the prerituximab era10 and has retained its prognostic value. The IPI assigns scores to clinical factors (Figure 1) and categorizes patients into 4 risk groups (0-1 = low, 2 = low-intermediate, 3 = high-intermediate, and 4-5 = high risk), with OS ranging from 26% to 73%. The revised IPI (R-IPI) was designed for patients treated with R-CHOP using the same clinical variables, divided patients into 3 risk groups with OS ranging from 55% to 94%.11 Finally, an NCCN-IPI (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) was developed with the same clinical predictors but differentiating scores according to age range, LDH value, and specific extranodal sites. NCCN-IPI categorized patients with scores of 0 to 8 into 4 groups with 5-year OS ranging from 33% to 96% and was able to delineate subgroups with the highest and lowest risk.12 All 3 prognostic indices were compared in the analysis of 2124 patients. NCCN-IPI had the best discrimination power for OS, with the greatest difference between the highest (NCNN-IPI = 6-8) and the lowest risk groups (0-1) with OS ranging from 49% to 92%.13 However, NCCN-IPI failed to identify patients with the worst prognosis and OS significantly below 50% (Table 1).

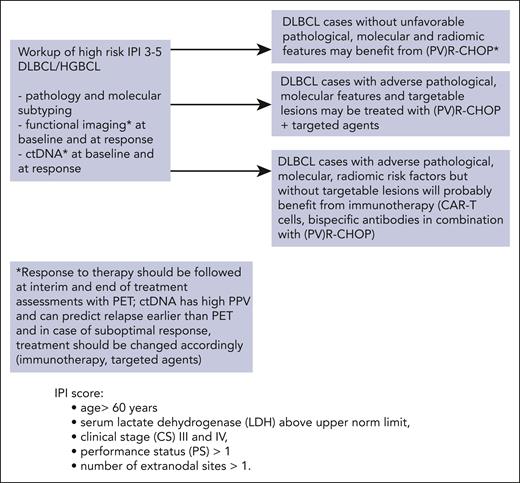

Proposed hypothetical pathway for clinical high risk (IPI 3-5) patients with DLBCL in future. An ideal workup should include molecular subtyping, functional imaging with radiomic risk assessment, and ctDNA measurements at the baseline and during treatment. Therapies should be adjusted for the various risk factors. Patients without other than clinical risk factors and with a good response to therapy might not need additional treatment other than standard (PV)R-CHOP. Notably, the addition of PV to R-CHOP requires the omission of vincristine (PV-R-CHP).

Proposed hypothetical pathway for clinical high risk (IPI 3-5) patients with DLBCL in future. An ideal workup should include molecular subtyping, functional imaging with radiomic risk assessment, and ctDNA measurements at the baseline and during treatment. Therapies should be adjusted for the various risk factors. Patients without other than clinical risk factors and with a good response to therapy might not need additional treatment other than standard (PV)R-CHOP. Notably, the addition of PV to R-CHOP requires the omission of vincristine (PV-R-CHP).

Summary of the most important risk features defining high-risk patients with DLBCL already used in clinical practice or in clinical trials with corresponding survival parameters

| Risk factors . | High-risk features . | Survival . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical factors | IPI = 3; high-intermediate | 5-y OS (43%-67%) | 10,13 |

| IPI = 4, 5; high risk | 5-y OS (26%-53.9%) | 10,13 | |

| R-IPI = 3 (3-5 risk factors) | 4-y OS (55%-60.9%) | 11,13 | |

| NCCN-IPI = 6-8; high risk | 5-y OS (33%-49%) | 12,13 | |

| Biological factors | COO = ABC subtype | 5-y OS (35%-56%) | 14,15 |

| COO = type 3 unclassifiable | 5-y OS (39%-62%) | 14,15 | |

| DEL | 5-y OS (30%-40%) | 16-18 | |

| DHL/THL | 2-y OS (38%-82%) | 19-22 | |

| DHTsig+ | 5-y TTP 57% | 23 | |

| Biological factors: molecular taxonomy | MCD/C5/MYD88 | 5-y OS (26%-60%) | 24-26 |

| N1 | 5-y OS (27%-40%) | 24,27 | |

| A53/C2 | 5-y OS 63% (33%-100%) | 24-26 | |

| BN2/C1/NOTCH2 | 5-y OS 67% (38%-100%) | 24-27 | |

| EZB DHTsig+ MYC+ | 5-y OS (40%-48%) | 24-27 | |

| Radiomics prognostic factors: baseline and dynamic | ΔSUVmax < 66% at iPET2 | 2-y OS 54.2% | 28 |

| High TMTV > 328 cm3 and ΔSUVmax < 66% at iPET2 | 2-y OS 37.1% | 28 | |

| ECOG-PS ≥ 2 and TMTV > 220 cm3 | 4-y OS (41%-61%) | 29 | |

| High-risk IMIPI | 3-y OS 51.5% | 30 | |

| High-risk clinical PET model | 2-y PFS 48.6% | 31 | |

| ctDNA: baseline and dynamic | No EMR | 2-y EFS 50% | 32 |

| No MMR | 2-y EFS 46% | 32 |

| Risk factors . | High-risk features . | Survival . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical factors | IPI = 3; high-intermediate | 5-y OS (43%-67%) | 10,13 |

| IPI = 4, 5; high risk | 5-y OS (26%-53.9%) | 10,13 | |

| R-IPI = 3 (3-5 risk factors) | 4-y OS (55%-60.9%) | 11,13 | |

| NCCN-IPI = 6-8; high risk | 5-y OS (33%-49%) | 12,13 | |

| Biological factors | COO = ABC subtype | 5-y OS (35%-56%) | 14,15 |

| COO = type 3 unclassifiable | 5-y OS (39%-62%) | 14,15 | |

| DEL | 5-y OS (30%-40%) | 16-18 | |

| DHL/THL | 2-y OS (38%-82%) | 19-22 | |

| DHTsig+ | 5-y TTP 57% | 23 | |

| Biological factors: molecular taxonomy | MCD/C5/MYD88 | 5-y OS (26%-60%) | 24-26 |

| N1 | 5-y OS (27%-40%) | 24,27 | |

| A53/C2 | 5-y OS 63% (33%-100%) | 24-26 | |

| BN2/C1/NOTCH2 | 5-y OS 67% (38%-100%) | 24-27 | |

| EZB DHTsig+ MYC+ | 5-y OS (40%-48%) | 24-27 | |

| Radiomics prognostic factors: baseline and dynamic | ΔSUVmax < 66% at iPET2 | 2-y OS 54.2% | 28 |

| High TMTV > 328 cm3 and ΔSUVmax < 66% at iPET2 | 2-y OS 37.1% | 28 | |

| ECOG-PS ≥ 2 and TMTV > 220 cm3 | 4-y OS (41%-61%) | 29 | |

| High-risk IMIPI | 3-y OS 51.5% | 30 | |

| High-risk clinical PET model | 2-y PFS 48.6% | 31 | |

| ctDNA: baseline and dynamic | No EMR | 2-y EFS 50% | 32 |

| No MMR | 2-y EFS 46% | 32 |

Values in brackets refer to survival parameters in different patient cohorts described in the cited publications.

Other clinical variables are also associated with adverse outcomes. These include a short time from diagnosis to treatment corresponding to an aggressive disease course,33 low vitamin D3 levels,34 hypercalcemia,35 and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio.36 However, these have not been routinely incorporated into prognostic indices.

Clinical prognostic indices using readily available factors are frequently used to identify patients at a risk of relapse in clinical practice. In clinical trials, IPI is frequently used as part of the eligibility criteria to focus study intervention on high-risk patients, most likely to benefit from intensified regimens, as well as a stratification factor during randomization to ensure balance of study arms. Recently, with the recognition that a long time from diagnosis to treatment might have impacted the results of some studies and resulted in overperformance of the control arm,33 some studies excluded patients with a long time from diagnosis to treatment.37 In contrast to prognostic utility of clinical factors, attempts to use these factors to guide therapy have been largely unsuccessful, as dicussed below.

Pathological and molecular prognostic factors

DLCBL NOS defined as a specific subtype of LBCLs, is characterized by significant clinical and biological heterogeneity. Pivotal work of Alizadeh et al identified, with gene expression profiling (GEP) method, 2 different subtypes of DLBCL related to the cell of origin (COO).38 The germinal center B-cell–like subtype (GCB) and activated B-cell–like subtype (ABC) resemble in genotype their counterparts in lymphoid cell development. Further work identified type 3 DLBCL with gene expression that was not linked to GCB or ABC.14 Patients with the ABC subtype have been described to have inferior outcomes compared with those with the type 3 and to GCB, with 5-year OS rates of 35%-56%, 39%-62% and 60%-78% for the ABC, type 3, and GCB subtypes, respectively.14,15 Noteworthy, in prospective trials such as the GOYA trial, the difference between GCB and ABC was less prominent, with 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 66% and 56% in the GCB and ABC subtypes, respectively.39 This clearly points toward biological and molecular heterogeneity within the respective COO subtypes and thus potentially an under-representation of patients with poor prognostic characteristics in these trials. Similarly, the ROBUST and PHOENIX trials prospectively enrolled patients with ABC or non-GCB DLBCL subtypes and showed better outcomes for these patients in the control arm compared with historic controls,40,41 pointing out difficulties in extrapolating results from retrospective studies into prospective trial designs, especially because of enormous biological and molecular heterogeneity.

The GEP method is not available in routine practice and alternative methods using immunohistochemistry (IHC) algorithms have been designed, with the Hans algorithm being the most widely used.42-44 Notably, there is a quite high discordance rate (15%-50%) between IHC models and the GEP method, leading to a high rate of misclassifications by IHC.45,46 New techniques designed for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies are better surrogates for GEP than IHC, including the Lymph2Cx assay, with >95% concordance between the 2 methods15 but their use in clinical practice remains limited.

Double expression of BCL2 and MYC (double expressor lymphomas [DELs]) has been shown to be a negative prognostic factor, with a 5-year OS between 30% and 40%.16-18 DELs occur more often within the ABC subtype but they form an unfavorable independent prognostic factor regardless of the COO.18

In accordance with the new World Health Organization classification, DLBCL cases with MYC and BCL2 rearrangements (R) belong to a new subtype—depending on cell morphology and growth pattern—called DLBCL/high-grade B-cell lymphomas (HGBL)-MYC/BCL2-R, that is, double-hit lymphoma (DHL) and in cases of additional BCL6 rearrangement—triple hit lymphoma (THL).1 According to the World Health Organization classification, lymphomas with MYC and BCL6 rearrangements have not been separately categorized but fall into either DLBCL or HGBL subtypes, as assessed by morphological features. The International Consensus Classification distinguishes both subtypes: HGBL with MYC/BCL6 and HGBL with MYC/BCL2 rearrangements47 DLBCL/HGBL-MYC/BCL2-R (DHL) have GC gene expression profiles, representing 5% to 10% of newly diagnosed DLBCL and have been reported to portend poor prognosis with long-term OS below 50%.19,20 Retrospective data suggests that intensifying therapy with R-DaEPOCH, R-Hyper CVAD/MA and R-CODOX-M/IVAC could improve outcomes; however, this has not been testified in a randomized study.21,22 Data from clinical trials have shown a 2-year OS of patients with DHL in the range of 63%.48 Discrepant results of survival in the DHL subgroup are related to bias in performing fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in the past. Ennishi et al delineated with GEP method a group of high-risk patients with a double-hit signature (DHITsig) and adverse prognosis. They belonged to the GCB subtype and had a 5-year time to progression (TTP) of 57% for DHITsig+ vs 81% DHITsig–, regardless of the MYC/BCL2 status.23 Notably, some MYC and BCL2 rearrangements are cryptic and cannot be detected by FISH.49 Acknowledging the rare occurrence of DHL, the paucity of clinical and molecular data, and conflicting results regarding their prognosis, patients with MYC/BCL2 rearrangements belong to a high-risk group with inferior survival after R-CHOP. There is no evidence from randomized trials concerning the best treatment choice and participation in clinical trials is encouraged. FISH testing for MYC-R, BCL2-R, and BCL6-R is the recommended diagnostic procedure for all patients with DLBCL.

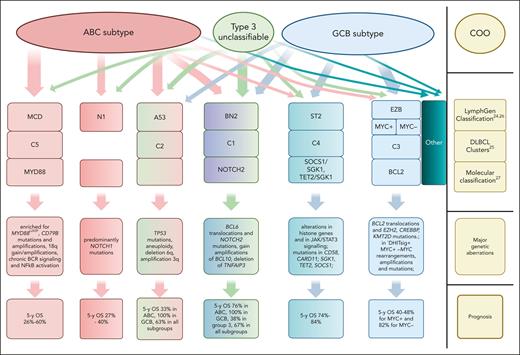

Recent studies have provided insights into the molecular alterations in DLBCL and paved the way for a future new taxonomy of DLBCL. Distinguishing new genetic subtypes has helped to understand the biological and clinical heterogeneity within and beyond COO groups and to identify patients with specific genetic alterations and different outcomes. Two pivotal studies by Schmitz et al and Chapuy et al have laid the foundation for this new molecular classification using whole exome sequencing (WES), DNA copy-number analysis, and targeted amplicon resequencing.24,25 This comprehensive genomic analysis of DLBCL has enabled the identification of mutations, somatic copy-number alterations, and structural variants. An analysis performed by Chapuy et al in the Harvard group found 98 mutations that were enriched in the examined cohort and a median of 17 genetic driver alterations per single DLBCL sample. Using the clustering method, 5 subtypes were identified: C1-C5 clusters with distinct genetic signatures but also with different survival probabilities and correlations to COO.25 The National Cancer Institute group applying WES identified 4 distinct genetic subgroups.24 This was later refined with additional research and as a result 7 genetic subtypes were distinguished; a special algorithm, available at https://llmpp.nih.gov/lymphgen/index.php was developed.26 A similar genetic classification was recapitulated by a research group from the United Kingdom27 (Figure 250).

Relationship between COO and probabilistic genetic subtypes as proposed by Schmitz et al,24Chapuy et al,25Lacy et al27(adapted from Wright et al26and de Leval et al50). Major genetic aberrations and prognosis are also shown. The width of the arrows and the solid color of the boxes correspond to the strength of the correlation between COO and molecular subtype. For example, the MCD/C5/MYD88 subtypes are assigned purely to the ABC group, whereas EZB/C3/BCL2 belongs almost exclusively to GCB subtypes. The molecular subtypes shown in boxes with color gradients include lymphomas originating from different COO groups. Notably, 37% of lymphomas cannot be assigned with sufficient probability to any of the molecular subtypes, as shown in the far-right panel. There is also a small subgroup of tumors called the composite group, presenting genetic aberrations characteristic of >1 molecular subtype (not shown in the figure). Taxonomy/abbreviations of the genetic subtypes are described in the cited original publications.

Relationship between COO and probabilistic genetic subtypes as proposed by Schmitz et al,24Chapuy et al,25Lacy et al27(adapted from Wright et al26and de Leval et al50). Major genetic aberrations and prognosis are also shown. The width of the arrows and the solid color of the boxes correspond to the strength of the correlation between COO and molecular subtype. For example, the MCD/C5/MYD88 subtypes are assigned purely to the ABC group, whereas EZB/C3/BCL2 belongs almost exclusively to GCB subtypes. The molecular subtypes shown in boxes with color gradients include lymphomas originating from different COO groups. Notably, 37% of lymphomas cannot be assigned with sufficient probability to any of the molecular subtypes, as shown in the far-right panel. There is also a small subgroup of tumors called the composite group, presenting genetic aberrations characteristic of >1 molecular subtype (not shown in the figure). Taxonomy/abbreviations of the genetic subtypes are described in the cited original publications.

Molecular taxonomy adds granularity to the COO classification and clearly helps discern subgroups of patients with different prognosis within the COO assignment.

Functional imaging: baseline and dynamic radiomic prognostic factors

Radiomic features of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), used at staging to evaluate disease burden and response to therapy, have been proven to have prognostic significance. Thus, PET-CT is considered the gold standard for DLBCL diagnosis, including response assessment. Many analyses have shown that higher total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) is associated with inferior PFS and/or OS.28,51 The prognostic value of the TMTV is an independent prognostic factor that can be enhanced when combined with biological and/or clinical risk factors.29,52 A new prognostic model—the International Metabolic Prognostic Index (IMPI)—was proposed by Mikhaeel et al. IMPI consists of MTV, age, and CS, and it defines better high-risk groups than IPI (https://petralymphoma.org/impi).30 Another model prognostic for OS was developed by LYSA.53 HOVON group designed “clinical PET” model, combining clinical and radiomic features: age, PS, MTV, SUVpeak, and Dmaxbulk (the maximum distance between the largest and any other lesion).54 Clinical PET was confirmed to have a higher positive predictive value (PPV) than IPI for PFS and TTP.31

Interim PET (iPET) has a high negative predictive value for PFS and EFS.55 A recently published study refined the criteria for the response and optimal timing of iPET as a prognostic factor and tool for the adaption of first-line treatment. Both iPET-2 and iPET-4 (after the 2nd and 4th therapy cycles, respectively) equally defined subgroups of patients with different prognosis, with iPET-4 and Deauville score (DS) 5 having the highest hazard ratio for PFS. The difference in the maximum standardized uptake value from the baseline (ΔSUVmax) assessed at iPET-2 and iPET-4 had a better predictive value than that measured only by DS4/5. DS 5 at iPET-2 and iPET-4 had the highest PPV for PFS. Hence, patients with DS5 at iPET-2 created a subgroup with the highest risk of disease relapse and could be identified very early as potential candidates for treatment modification. Similarly, patients with DS4/5 and/or ΔSUVmax < 70% on iPET-4 are at risk of treatment failure.56

Circulating tumor DNA as a prognostic factor at baseline and during treatment

Measurement of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has become another tool to assess tumor volume and predict treatment outcomes. Since the seminal papers published by Scherer57 and Kurtz,32 numerous reports have shown a correlation between pretreatment ctDNA and survival. Analysis of ctDNA in 217 patients with DLBCL showed that high levels of ctDNA predicted unfavorable EFS and OS. In multivariate analysis (MVA), ctDNA remained an independent prognostic factor for EFS. The dynamics of ctDNA was strongly associated with the response to therapy. Rapid decline of ctDNA levels at the start of therapy cycle 2, and deep reduction >2.5 log at cycle 3, termed an early and major molecular response (EMR and MMR, respectively), characterized patients who achieved complete response (CR). It was prognostic for EFS and OS, with patients without EMR and MMR having significantly worse survival.32 The importance of ctDNA dynamics as a prognostic factor was also confirmed in data from the prospective phase 3 POLARIX and Nordic phase 2 trials.58,59

A complex prognostic model (continuous individualized risk index [CIRI]) integrating clinical, molecular, and radiomic features was proposed by Kurtz et al, which comprises pretreatment and dynamic factors: IPI, molecular COO, iPET, baseline ctDNA, EMR, and MMR (https://ciri.stanford.edu).60

The above-mentioned studies clearly showed that ctDNA could be a powerful tool to define high-risk patients with DLBCL before and after treatment. Ongoing and future trials will determine whether ctDNA measurements can improve patient outcomes through treatment adaptation, according to the results of ctDNA genotyping.

Treatment optimization: intensification of the 1st line chemotherapy

As shown above, with increasing knowledge of tumor biology and refinement of diagnostic methods, clinicians have many tools to identify high-risk patients with DLBCL. Strategies used to improve their outcomes include enrichment of first-line immunochemotherapy with new targeted agents, application of immunotherapy in the early stage of disease and adjusting therapy according to dynamic risk factors.

Early attempts to improve patient outcomes with the substitution of rituximab with obinutuzumab–type 2 anti-CD20 antibody or intensification of chemotherapy have not been successful.39,48,61,62 The MegaCHOEP trial included patients aged <60 years with age-adjusted (aa) IPI 2-3 and randomized them between R-CHOP and dose-escalated regimen with ASCT. Patients in the R-MegaCHOEP arm did not have any survival benefit but experienced more grade 3/4 hematological toxicity and infections.62 No difference in OS and PFS was observed in a randomized phase 3 Alliance/CALGB50303 trial, which studied the efficacy of dose-intensive R-DaEPOCH vs R-CHOP-21 in the front-line setting.63 Notably, on post hoc analysis, an improvement in PFS but not OS was noticed in patients with IPI 3-5. The negative results of the study could have been attributed to the fact that the standard arm achieved a very favorable 2-year OS of 85.7% and high-risk patients were underrepresented. Strategies for consolidation of first-line R-CHOP with HDT/ASCT failed to provide OS benefit. The Italian group showed that in the cohort of high-risk patients with aaIPI 2-3, consolidation with HDT/ASCT resulted in increased 2-year failure-free survival but without a difference in OS.64 Similarly, in a randomized study by Stiff et al HDT/ASCT did not result in a survival advantage in the entire cohort of patients with an IPI of 3-5. However, in the subgroup analysis, a survival benefit of consolidation with ASCT was noticed in the high-risk group.65

Treatment optimization in the 1st line: R-CHOP + X concept

Endeavor to overcome adverse prognosis of high-risk patients resulted in designing randomized trials for newly diagnosed patients with DLBCL comparing R-CHOP + X to standard R-CHOP, where “X” were novel drugs mainly selected according to their activity in relapsed setting but also to their biological mechanisms of action. Despite the encouraging results of new agents for relapsed disease, the outcomes of these trials have been, until recently, largely disappointing. The only study exploiting the concept R-CHOP + X, which met its primary end point, was the POLARIX study, investigating the antibody-drug-conjugate polatuzumab vedotin (PV) (antiCD-79b antibody conjugated with monomethyl auristatin E) in combination with R-CHP in first-line patients with DLBCL with IPI 2-5.66 PV-R-CHP demonstrated a 27% reduction in the relative risk of disease progression, relapse, or death compared with R-CHOP, with similar toxicity profiles. The difference in the 2-year PFS was 6.5%, with no impact on OS, which may reflect the current better therapeutic options for relapsed and refractory disease. Although the trial was not powered to detect differences between subgroups, an exploratory analysis showed a PFS benefit for patients >60 years, with the ABC subtype and IPI 3-5. PV with R-CHP has recently been approved as the first-line treatment.

A deeper understanding of molecular DLBCL subtypes helped identify patients who benefited from adding new X drugs in trials, which otherwise were negative for the whole patient population. The REMoDL-B study examined the addition of bortezomib to R-CHOP and stratified the patients according to their COO using GEP. In the primary analysis with a median follow-up of 30 months, the experimental arm did not show any improvement in survival.67 However, additional analysis after 5 years unexpectedly showed differences in OS and PFS for specific molecular subtypes. Although no benefit of combination therapy was seen in the whole group, the addition of bortezomib significantly improved patient outcomes in the ABC and molecular high-grade subgroups.68 PHOENIX was another trial designed according to the R-CHOP + X scheme and investigated R-CHOP + ibrutinib vs R-CHOP in patients with the DLBCL non-GCB subtype (COO established using IHC criteria) and IPI ≥ 1. The study failed to meet the primary end point, which was the difference in the EFS.40 However, in an unplanned analysis, R-CHOP + ibrutinib improved EFS and OS in a group of patients <60 years. In patients aged >60 years, there was an increased toxicity of ibrutinib, which impaired the timely delivery of chemotherapy. Retrospective genomic profiling identified 2 molecular subgroups that achieved outstanding survival compared with the standard arm, namely the MCD and N1 subgroups, both with adverse prognosis. The 3-year EFS and OS of MCD and N1 patients aged <60 years treated with R-CHOP + ibrutinib were 100% for both parameters vs 42.9% and 50% for EFS, and 69.6% and 50% for OS, respectively, in the R-CHOP arm.69 These unexpected positive results confirming the activity of BTK inhibitors in subsets of patients with non-GCB prompted researchers to design new trials using 2nd generation BTK-inhibitor, acalabrutinib. Two ongoing phase 3 trials are evaluating the addition of acalabrutinib to R-CHOP vs R-CHOP in newly diagnosed DLBCL: REMoDL-A70 and ESCALADE.71 E1412 was a large, randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide plus R-CHOP vs R-CHOP in all commers DLBCL, in which lenalidomide was associated with improved PSF and OS.72 In contrast, a phase 3 study using this approach focused on ABC DLBCL (ROBUST) did not show the benefit of the addition of lenalidomide,41 possibly due to the under-representation of high-risk patients in the latter study. The median time from diagnosis to treatment was 31 days in the ROBUST study vs 20 days in the E1412 study, demonstrating some of the difficulties in real-time implementation of molecular profiling and its impact on the selection of lower-risk patients able to wait for molecular analysis results.

The phase 3 randomized, double-blinded FRONT-MIND trial builds on E1412 by investigating the addition of anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody tafasitamab and lenalidomide to the R-CHOP vs R-CHOP arm in high-risk patients with DLBCL with IPI 3-5.73 Patients eligible for the FRONT-MIND trial were <28 days from diagnosis based on the biopsy date—an attempt to avoid sections of low-risk patients entering the study. This trial has completed accrual and the results of this trial, and other first-line studies will hopefully open ways to the improvement of the outcomes of high-risk patients.

Treatment optimization: response–adapted 1st line therapy using dynamic risk factors

As mentioned previously, the definition of a high-risk population is not limited to factors identified at diagnosis but also captures features assessed during and after treatment, such as the absence of metabolic response: DS5 at iPET2 or DS4/5 and/or ΔSUVmax <70% at iPET4, MRD+ disease at the end of treatment, and lack of EMR and MMR after the second cycle of therapy. Response–adapted therapy strategies with intensified chemotherapy have been studied previously by various research groups, but no clear advantage in terms of survival has been observed.74-77 In the PETAL trial, patients were treated with 2 cycles of R-CHOP. Those with positive PET results (ΔSUVmax < 66%) were randomized to receive chemotherapy according to the Burkitt protocol or continue R-CHOP. This strategy did not result in any survival benefit but induced significantly higher toxicity.74 Hence, high-risk patients with chemorefractory disease, defined by a suboptimal response at interim assessment, require other approaches, that is, targeted agents or immunotherapy. Ongoing SAKK 38-19 trial is evaluating whether the addition of acalabrutinib to R-CHOP after 2 cycles of therapy in patients with positive iPET and/or a lack of molecular response will improve outcomes.78

A response–adapted therapy approach was tested in the ZUMA-12 trial, which included high-risk patients with IPI ≥ 3 and/or DHL/THL. Patients with DS 4/5 on iPET after 2 cycles of therapy were referred for CAR T-cell therapy. Overall, 37/40 patients received the product (axicabtagene ciloleucel [axi-cel]), with a high CR rate of 78% and overall response rate (ORR) of 89%; the median duration of response, PFS, and EFS were not reached.79 Noteworthy, patients achieved a higher number of CAR T cells in the final product, and higher peaks of CAR T cells were noted compared with leukapheresis products from patients after more lines of therapy. This may advocate the use of CAR T cells in earlier lines of therapy in high-risk patients with DLBCL.

Treatment optimization in the 1st line using immunotherapy

The introduction of CAR T cells has revolutionized treatment paradigms for relapsed or refractory DLBCL,5-9 setting them as the treatment choice in refractory and early relapsing patients after 1st line therapy,5,9 instead of HDT/ASCT, with clear benefits in PFS and OS. Median OS was not reached in axi-cel arm vs 31.1 months in standard HDT/ASCT arm, with PFS of 14.7 months vs 3.7 months.5 CAR T cells are being tested in the first-line setting in the ZUMA-23 trial, which recruits high-risk patients with DLBCL, HGBCL, transformed marginal zone, and follicular lymphoma with an IPI ≥ 4. After 1 cycle of R-chemotherapy, patients are randomized to a standard arm (5 × R-CHOP or R-DaEPOCH) or an experimental CAR T-cell arm (axi-cel).80 This study will set the role of CAR T cells in the first-line treatment of high-risk patients with DLBCL/HGBCL.

Bispecific anti-CD20xCD3 monoclonal antibodies have proved their efficacy in relapsed disease in heavily pretreated populations. They elicit responses in the range of ORR 52%, CR 39% (glofitamab),81 and ORR 63%, CR 39% (epcoritamab),82 with some long-term CRs lasting beyond the end of therapy, which could suggest the curative potential of these agents. These agents have been tested and are still under investigation in the first line. Glofitamab was tested in phase 1b with R-CHOP giving high ORRs of 93.5% and complete metabolic responses of 76.1%, with low incidence of cytokine release syndrome.83 A study combining glofitamab with PV-R-CHP in newly diagnosed patients with DLBCL with an IPI of 2-5 is underway.84 The combination of epcoritamab and R-CHOP in a phase 1b/2 study in 47 high-risk patients with DLBCL (IPI 3-5) resulted in an ORR of 100% and CR of 76%; equally good results were seen in patients with DHL/THL, with a manageable safety profile.85 The addition of epcoritamab to R-CHOP is being evaluated in a phase 3 randomized trial in patients with DLBCL IPI 3-5.86 Immunotherapy in the early stages of treatment has some clear advantages: it uses more robust and fit immune cells and elicits more potent immune responses in comparison to patients after many lines of therapy, as shown in ZUMA-12. It is also indifferent to molecular subtypes, enabling patients to enter trials without the need to perform molecular assays before treatment (Figure 1).

Conclusions

Results of trials using targeted therapies, coming from post hoc analyses, show a clear survival benefit in some groups of patients with unfavorable prognosis, including molecular high-risk. Moreover, the activity of the targeted agents confirmed the biological rationale of such approaches, as in the case of ibrutinib in the MCD subgroup. However, the molecular mechanisms standing behind activity of BTK inhibition in the N1 subtype remain to be elucidated. Similarly, biologically driven differences in patient outcomes in the POLARIX study87 confirm the importance of including broad groups of patients in trials and performing biological studies. Thus, the outcomes of clinical trials can inspire and fuel basic research in tumor biology, which in turn paves the way for the development of new therapies. These examples support designing new trials in “all comers” fashion, thus enabling wider population of patients to take advantage of novel agents. High-risk patients create a group that could potentially gain the greatest benefit from new therapies; however, their participation is limited by poor performance status, which is strictly related to disease biology. To achieve this goal, changes should be introduced in the design of clinical trials to include more high-risk patients, such as liberalization of inclusion criteria and decentralization of trial sites. Conversely, biomarker-informed studies could save resources by limiting the study population to selected groups and preventing patients from overtreatment. Molecular correlative studies have become an indispensable part of current clinical trials and will probably become a part of clinical practice in the near future. The use of immunotherapy in patients with refractory DLBCL has already prolonged their survival and overcome adverse prognosis. Moving immunotherapy to earlier stages of treatment and the use of biomarker-informed therapies will probably improve the outcomes of high-risk patients with DLBCL.

Acknowledgment

Graphics were created with BioRender.com.

Authorship

Contribution: A.D.-I. and G.S.N. designed the research, summarized the data, and wrote and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.S.N. reports consultancy from Blueprint Medicines, Bantam Pharmaceuticals LLC, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Kite Pharma Inc, Kymera Therapeutics, TG Therapeutic, Inc, Zai Lab Limited, Selvita Inc, Debiopharm, Ryvu Therapeutics, Celgene Corporation, Morphosys AG, Genentech Inc, Fate Therapeutics, MEI Pharma Inc, Curis, Incyte Corporation, ADC Therapeutics, Seagen, Bristol Myers Squibb, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Limited, Daiichi Sankyo, and Constellation Pharmaceuticals. A.D.-I. received travel grants from AbbVie and Gilead and consultancy from AbbVie.

Correspondence: Anna Dabrowska-Iwanicka, Department of Lymphoid Malignancies, Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, 5 WK Roentgen St, Warsaw 02-781, Poland; email: anna.dabrowska-iwanicka@nio.gov.pl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal