In this issue of Blood, Koury et al describe the improvement in clinical outcomes of adults diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) in 5 Latin American countries from 2005 to 2020 because of work of the International Consortium on Acute Leukemia (ICAL).1

APL was once the most dreaded and “most malignant form of acute leukemia,”2 with patients experiencing “a very rapid fatal course of only a few weeks.”2 Since the introduction of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and anthracycline-based chemotherapy followed by ATRA and arsenic-based regimens, APL has been widely considered to be 1 of the most curable leukemias, with current remission rates of 90% to 95% and long-term survival in >80% of patients.3 What is often overlooked, however, is the fact that these excellent outcomes are achieved only in well-resourced, high-income nations. In the rest of the world, many patients lacking access to trained medical professionals, accurate diagnostic testing, and availability to effective drugs still experience the same rapidly fatal outcomes as originally described. To address this critical issue, in 2004, the international members of the American Society of Hematology formed the ICAL. The long-term results of the interventions instituted by the ICAL in 5 countries (Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay) over 15 years are detailed here in this landmark article.1 As described, the ICAL established clinical networks within each Latin American country to train medical personnel on APL diagnosis and treatment, expanded local infrastructure and laboratories for genetic testing, and ensured drug access and availability by petitioning local government and pharmaceutical companies.

The authors report the long-term results of 806 adult patients, aged 15 to 75 years, who were diagnosed and treated for de novo APL with modified standard ATRA and anthracycline chemotherapy over a 15-year period (2005-2020). Therapy was administered per the Progama para el Tratamiento de Hemopatias Malignas (PETHEMA)/Hemato-Oncologie Voor Volwassenen Nederland (HOVON) LPA 2005,4 with substitution of daunorubicin (more readily available and cheaper) in place of idarubicin during induction. As per the follow-up publication, incorporation of cytarabine and higher daunorubicin doses during consolidation was instituted for high- and intermediate-risk disease, respectively.5 The main causes of death in these patients were induction mortality due to bleeding and infections with higher mortality occurring in individuals with more advanced risk disease (ie, higher white blood cell count at presentation), poor functional status, central nervous system disease, and delay between symptoms and diagnosis of >48 hours.

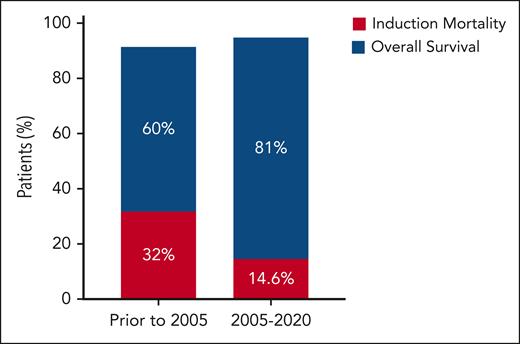

Although early outcomes of these interventions have previously been reported,6,7 what is impressive here is the sustained improvement in clinical outcomes in these countries, specifically a 50% reduction in induction-related mortality (from 32% to 14.6%) and an ≈20% improvement in long-term overall survival (estimated 4-year overall survival of 81% compared with 52%-60% previously)8 with a median follow-up of 53 months (see figure). This is especially remarkable, given that most of these patients with APL had high- and intermediate-risk disease and received cytotoxic chemotherapy plus ATRA throughout their disease course.

Areas of continued improvement clearly remain. For instance, as the authors point out, the prolonged time from initial symptom presentation to APL confirmation and treatment in these countries (ie, >10 days in some countries) remains challenging and was directly associated with higher induction mortality and risk of relapse in this study. More importantly, the induction mortality of almost 15% clearly is much greater than that reported (7%-9%) in patients treated with the same regimen in higher-income countries.5 One obvious approach to address this is to substitute arsenic in place of cytotoxic chemotherapy in combination with ATRA for low- to intermediate-risk disease. Although this would be expected to reduce cytopenias with decreased bleeding and infectious-related mortality,9 the availability and ease of administration of intravenous arsenic in these areas remain open questions. Furthermore, these outcomes did not include patients with therapy-related APL, those aged <15 or >75 years, or those with suboptimal organ function; and patients in countries who did not have ready access to supportive care measures, such as frequent transfusion support.

Nevertheless, the members of the International Consortium of Acute Leukemia should be applauded. Despite the innumerable challenges and obstacles, the long-term clinical outcomes achieved by >800 patients with APL in these 5 countries (Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay) clearly show that the changes wrought by the ICAL have permanently altered the trajectory of this disease in these areas. Many years ago, it was said that APL was converted from a deadly disease into a highly treatable one by the advent of ATRA added to anthracycline.3 However, one can argue that in addition to ATRA, it also required the concerted and dedicated efforts of an international group of hematologists to truly transform APL from a “highly fatal to highly curable” disease in these Latin American countries. The results of ICAL should serve as a model moving forward as to what can be accomplished by a worldwide collaboration of medical professionals and their impact on global hematology outcomes.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: E.S.W. has no specific conflicts of interest in relation to this commentary. Other conflicts of interest to report include advisory/consulting roles at AbbVie, Blueprint, Daiichi Sankyo, Immunogen, Kite, Kura, Qiagen, Rigel, Schrodinger, Stemline, and Syndax; speaking engagements for Pfizer, Astellas, and Dava Oncology; data safety monitoring committees for Gilead and AbbVie; and section editorship role for Up To Date.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal