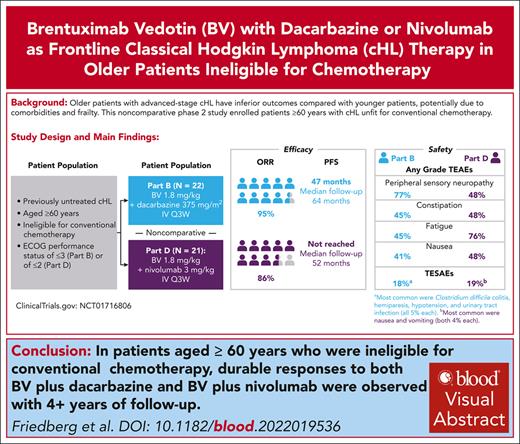

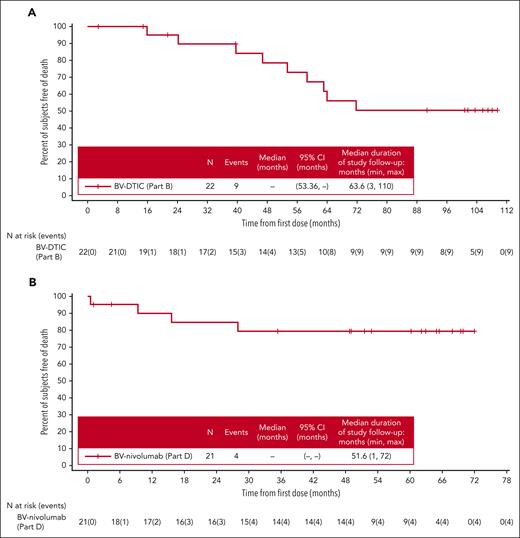

With a median follow-up of 63.6 months, mPFS of patients aged ≥60 years with cHL treated with upfront BV-DTIC was 47.2 months.

Noncomparatively, mPFS of patients aged ≥60 years with cHL treated with BV-nivolumab was not reached with a median follow-up of 51.6 months.

Visual Abstract

Older patients with advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) have inferior outcomes compared with younger patients, potentially due to comorbidities and frailty. This noncomparative phase 2 study enrolled patients aged ≥60 years with cHL unfit for conventional chemotherapy to receive frontline brentuximab vedotin (BV; 1.8 mg/kg) with dacarbazine (DTIC; 375 mg/m2) (part B) or nivolumab (part D; 3 mg/kg). In parts B and D, 50% and 38% of patients, respectively, had ≥3 general comorbidities or ≥1 significant comorbidity. Of the 22 patients treated with BV-DTIC, 95% achieved objective response, and 64% achieved complete response (CR). With a median follow-up of 63.6 months, median duration of response (mDOR) was 46.0 months. Median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 47.2 months; median overall survival (mOS) was not reached. Of 21 patients treated with BV-nivolumab, 86% achieved objective response, and 67% achieved CR. With 51.6 months of median follow-up, mDOR, mPFS, and mOS were not reached. Ten patients (45%) with BV-DTIC and 16 patients (76%) with BV-nivolumab experienced grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events; sensory peripheral neuropathy (PN; 27%) and neutropenia (9%) were most common with BV-DTIC, and increased lipase (24%), motor PN (19%), and sensory PN (19%) were most common with BV-nivolumab. Despite high median age, inclusion of patients aged ≤88 years, and frailty, these results demonstrate safety and promising durable efficacy of BV-DTIC and BV-nivolumab combinations as frontline treatment, suggesting potential alternatives for older patients with cHL unfit for initial conventional chemotherapy. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01716806.

Introduction

The overall survival (OS) of adult patients with advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) has improved dramatically over the past 2 decades because of refinements in chemotherapy, response-adapted approaches, novel salvage options, and enhanced supportive care.1-3 Up to 20% of patients with cHL are aged ≥60 years,4-6 and outcomes in older patients are inferior to outcomes in younger patients. For example, in the E2496 and ECHELON-1 trials, patients aged ≥60 years had long-term OS of 58% and 74%, respectively, compared with >90% for patients aged <60 years.3,7

In a recent analysis of Medicare patients aged ≥65 years, only 25% were treated with full-course chemotherapy, 50% received partial regimens or single-agent treatment, and 26% received no therapy.8 Improved survival is observed with full-course chemotherapy; however, this is confounded by selection bias because patients with comorbidities and frailty are less likely to be treated with these regimens.9,10 Established guidelines emphasize there is no treatment standard for patients aged ≥60 years with cHL, and clinical judgment with goals of minimizing toxicity and maximizing efficacy is important.

With the introduction of brentuximab vedotin (BV) and checkpoint inhibitors into the cHL armamentarium, there is enthusiasm to evaluate these agents in older patients. A sequential therapy approach of single-agent BV, followed by chemotherapy, and then BV maintenance therapy demonstrated favorable outcomes in patients who could complete the regimen.11

We previously reported that BV as a monotherapy and in combination with dacarbazine (DTIC) has yielded response rates >90%, with a median duration of response (mDOR) of 9 months and 45 months, respectively.12 In younger patients with relapsed or refractory cHL, the combination of BV-nivolumab also confers high and durable complete response (CR) rates, although 74% of patients also received per-protocol autologous stem cell transplant after BV-nivolumab treatment.13 Herein, we provide long-term follow-up data on the BV-DTIC combination and report on a subsequent multicenter phase 2 trial that evaluated the safety and antitumor activity of combination therapy with BV-nivolumab in previously untreated older patients with cHL.

Methods

SGN35-015 (NCT01716806) was a phase 2, open-label study of BV as monotherapy or in combination as frontline therapy. The trial was approved by the institutional review board at each participating institution and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent.

There were 6 parts in the study: part A (BV), part B (BV-DTIC), part C (BV-bendamustine), part D (BV-nivolumab), part E (BV), and part F (BV). This manuscript reports the final results from parts B and D of the study. In parts B and D of the study, eligibility criteria (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website) included patients aged ≥60 years with histologically confirmed newly diagnosed cHL who were ineligible for or had declined initial conventional combination chemotherapy and who had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of ≤3 (part B) or ≤2 (part D). Key exclusion criteria included prior immuno-oncology therapy, kidney disease requiring ongoing dialysis, and grade ≥2 peripheral neuropathy (PN). Patients were treated with BV (1.8 mg/kg) and DTIC (375 mg/m2) in part B of the study and treated with BV (1.8 mg/kg) and nivolumab (3 mg/kg) in part D on day 1 of each 3-week cycle for up to 16 cycles. They could continue per investigator decision until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The primary end point, objective response rate (ORR), was assessed by the investigator according to Cheson et al14 for BV-DTIC and the Lugano Classification and the Lymphoma Response to Immunomodulatory Therapy Criteria for BV-nivolumab.15,16 For both BV-DTIC and BV-nivolumab cohorts, computed tomography scans were performed at baseline, cycles 2, 4, 8, and 12, and at end of therapy (EOT). Positron emission tomography (PET) scans were also performed at cycles 2 and 8 for BV-DTIC and cycles 4, 8, and 12 for BV-nivolumab. After completion of therapy, disease status was assessed by computed tomography at intervals of at least every 6 months for the first 2 years, an annual assessment for the third year, and then per institutional standard of care until disease progression. Per the protocol, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was optional, and patients received G-CSF at the discretion of the investigator or per institutional standards.

The ORR and CR rate and their respective 2-sided 95% exact confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with the Clopper-Pearson method.17 Time-to-event end points (DOR, progression-free survival [PFS], and OS) were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methodology with 2-sided 95% CIs computed from the complementary log-log transformation method.18 Comprehensive geriatric assessment was performed by using components from a tool developed and evaluated by Hurria et al.19 Assessment variables from the tool included aspects of function, comorbidity, cognition, psychological state, social activity/support, and nutritional status. For both the BV-DTIC and BV-nivolumab cohorts, a sample size of 20 in each cohort was planned to detect an ORR of >25%, which was considered to show minimal clinical benefit given that this patient population may not have other options for initial conventional chemotherapy. With an overall significance level of 0.1, observing ≥9 objective responses among 20 patients (45% ORR with lower bound of exact 90% CI, 25.9%) would indicate a true ORR of >25%.

Results

Brentuximab and dacarbazine cohort

Twenty-two patients with cHL were enrolled and treated with BV-DTIC. The median age was 69 years (range, 62-88), and most patients were male (73%) with stage III/IV disease (73%) and an ECOG performance status of ≤1 (68%) (Table 1). Seven patients (32%) had an ECOG performance status of 2, and none had an ECOG performance status of 3. Comprehensive geriatric assessment was completed on all patients at baseline (Table 2). Seventy-three percent of patients reported limitations to performing physical functioning tasks, and 50% of patients had ≥3 comorbidities in general or at least 1 comorbidity that significantly interfered with quality of life. Forty-one percent of patients treated with BV-DTIC took >13.5 seconds to complete the “up and go” test.

Summary of demographics and patient characteristics (full analysis set)

| Category/variable . | Part B (n = 22), n (%) . | Part D (n = 21), n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||

| n | 22 | 21 |

| Mean (STD) | 74.0 (9.0) | 72.1 (7.8) |

| Median | 69.0 | 72.0 |

| Min, max | 62, 88 | 60, 88 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 16 (73) | 15 (71) |

| Female | 6 (27) | 6 (29) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (18) | 1 (5) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 18 (82) | 20 (95) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Black or African American | 3 (14) | 2 (10) |

| White | 19 (86) | 19 (90) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| n | 22 | 21 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.7 (5.2) | 28.4 (6.2) |

| Median | 26.1 | 28.1 |

| Min, max | 18, 36 | 18, 49 |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| Grade 0 | 6 (27) | 4 (19) |

| Grade 1 | 9 (41) | 16 (76) |

| Grade 2 | 7 (32) | 0 |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Disease stage at initial diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Stage I | 4 (18) | 3 (14) |

| Stage II | 2 (9) | 1 (5) |

| Stage III | 9 (41) | 10 (48) |

| Stage IV | 7 (32) | 6 (29) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Histologic subtype, n (%) | ||

| Nodular sclerosis | 9 (41) | 7 (33) |

| Mixed cellularity | 9 (41) | 2 (10) |

| Lymphocyte-rich | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Not otherwise specified | 3 (14) | 8 (38) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Category/variable . | Part B (n = 22), n (%) . | Part D (n = 21), n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||

| n | 22 | 21 |

| Mean (STD) | 74.0 (9.0) | 72.1 (7.8) |

| Median | 69.0 | 72.0 |

| Min, max | 62, 88 | 60, 88 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 16 (73) | 15 (71) |

| Female | 6 (27) | 6 (29) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (18) | 1 (5) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 18 (82) | 20 (95) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Black or African American | 3 (14) | 2 (10) |

| White | 19 (86) | 19 (90) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| n | 22 | 21 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.7 (5.2) | 28.4 (6.2) |

| Median | 26.1 | 28.1 |

| Min, max | 18, 36 | 18, 49 |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||

| Grade 0 | 6 (27) | 4 (19) |

| Grade 1 | 9 (41) | 16 (76) |

| Grade 2 | 7 (32) | 0 |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Disease stage at initial diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Stage I | 4 (18) | 3 (14) |

| Stage II | 2 (9) | 1 (5) |

| Stage III | 9 (41) | 10 (48) |

| Stage IV | 7 (32) | 6 (29) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Histologic subtype, n (%) | ||

| Nodular sclerosis | 9 (41) | 7 (33) |

| Mixed cellularity | 9 (41) | 2 (10) |

| Lymphocyte-rich | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Not otherwise specified | 3 (14) | 8 (38) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (5) |

Max, maximum; Min, minimum; SD, standard deviation; y, years.

Summary of geriatric assessment questionnaire at baseline in part B (BV-DTIC) (full analysis set)

| Category/variable . | Part B (n = 22), n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Physical functioning, no. of items [10] | |

| Patients who reported “limited a lot” with ≥1 task | 16 (73) |

| Instrumental activities of daily living, no. of items [7] | |

| Patients who are completely dependent on ≥1 task | 2 (9) |

| OARS Comorbidity, no. of items [15] | |

| Patients who have 3 or more comorbidities or at least 1 comorbidity, that significantly interferes with QoL | 11 (50) |

| Time to perform “up and go,” no. of items [1] | |

| >13.5 s | 9 (41) |

| Someone to help if you were confined to bed, no. of items [1] | |

| None or a little of the time | 2 (9) |

| Someone to help you with daily chores if you were sick, no. of items [1] | |

| None or a little of the time | 1 (5) |

| Percentage unintentional weight loss in last 6 mo, no. of items [1] | |

| ≥10% | 5 (23) |

| Blessed orientation-memory-concentration test, no. of items [1] | |

| >6 | 7 (32) |

| Category/variable . | Part B (n = 22), n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Physical functioning, no. of items [10] | |

| Patients who reported “limited a lot” with ≥1 task | 16 (73) |

| Instrumental activities of daily living, no. of items [7] | |

| Patients who are completely dependent on ≥1 task | 2 (9) |

| OARS Comorbidity, no. of items [15] | |

| Patients who have 3 or more comorbidities or at least 1 comorbidity, that significantly interferes with QoL | 11 (50) |

| Time to perform “up and go,” no. of items [1] | |

| >13.5 s | 9 (41) |

| Someone to help if you were confined to bed, no. of items [1] | |

| None or a little of the time | 2 (9) |

| Someone to help you with daily chores if you were sick, no. of items [1] | |

| None or a little of the time | 1 (5) |

| Percentage unintentional weight loss in last 6 mo, no. of items [1] | |

| ≥10% | 5 (23) |

| Blessed orientation-memory-concentration test, no. of items [1] | |

| >6 | 7 (32) |

Geriatric assessment questionnaire used components from a tool developed and evaluated by Hurria et al.19

No., number; OARS, Older Americans Resources and Services questionnaire; QoL, quality of life.

Additional baseline characteristics are described in supplemental Table 2. The ORR was 95% (95% CI, 77.2-99.9), and the CR rate was 64% in the full analysis set (all treated patients) (supplemental Table 3). The median duration of CR had not been reached (95% CI, 14.7 months-not estimable). With a median follow-up of 63.6 months, mDOR was 46.0 months (supplemental Figure 1A). The median PFS (mPFS) (Figure 1A) was 47.2 months, and the median OS (mOS) (Figure 2A) had not yet been reached in the full analysis set (95% CI for mPFS, 10.8 months-not estimable; 95% CI for mOS, 53.4 months-not estimable). For the 12 patients treated with BV-DTIC who then did not receive any subsequent cancer-related therapies, the 5-year OS rate was 90% (95% CI, 47-99), and the median duration of follow-up after first dose was 96.13 months. Of the 21 patients who were evaluated by PET at cycle 2, a total of 14 (67%) were PET negative, and 7 (33%) were PET positive. Of the 6 patients who were evaluated at EOT, 3 (50%) were PET negative, and 3 (50%) were PET positive; PET was not required after CR was reached.

PFS for patients treated with BV-DTIC (part B) or BV-nivolumab (part D) (full analysis set). (A) For patients treated with BV-DTIC, mPFS was 47.2 months (95% CI, 10.78-not estimable) at a median follow-up of 63.6 months, and there were 8 PFS events among 22 patients. (B) For patients treated with BV-nivolumab, mPFS has not been reached yet (95% CI, 9.36-not estimable), and 8 PFS events have occurred among 21 patients with a median follow-up of 51.6 months. Censored patients are denoted by hash marks. PD, progressive disease.

PFS for patients treated with BV-DTIC (part B) or BV-nivolumab (part D) (full analysis set). (A) For patients treated with BV-DTIC, mPFS was 47.2 months (95% CI, 10.78-not estimable) at a median follow-up of 63.6 months, and there were 8 PFS events among 22 patients. (B) For patients treated with BV-nivolumab, mPFS has not been reached yet (95% CI, 9.36-not estimable), and 8 PFS events have occurred among 21 patients with a median follow-up of 51.6 months. Censored patients are denoted by hash marks. PD, progressive disease.

OS for patients treated with BV-DTIC (part B) or BV-nivolumab (part D) (full analysis set). (A) For patients treated with BV-DTIC, mOS has not been reached yet (95% CI, 53.36-not estimable) at a median follow-up of 63.6 months, and there were 9 OS events among 22 patients. (B) For patients treated with BV-nivolumab, mOS has not been reached yet (95% CI, not estimable-not estimable) at a median follow-up of 51.6 months, and 4 OS events occurred among 21 patients. Censored patients are denoted by hash marks.

OS for patients treated with BV-DTIC (part B) or BV-nivolumab (part D) (full analysis set). (A) For patients treated with BV-DTIC, mOS has not been reached yet (95% CI, 53.36-not estimable) at a median follow-up of 63.6 months, and there were 9 OS events among 22 patients. (B) For patients treated with BV-nivolumab, mOS has not been reached yet (95% CI, not estimable-not estimable) at a median follow-up of 51.6 months, and 4 OS events occurred among 21 patients. Censored patients are denoted by hash marks.

The median number of cycles of BV was 12.5 per patient, and the median number of cycles of DTIC was 12.0 per patient. Three patients received >16 cycles of BV, whereas none received >16 cycles of DTIC. The median duration of treatment for patients treated with BV-DTIC was 37.6 weeks. The duration of treatment for BV-nivolumab and the associated timepoints of best response are listed in supplemental Table 4. Seven of 22 patients (32%) treated with BV-DTIC received G-CSF. Three patients (14%) had experienced neutropenia.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) are summarized in supplemental Table 5. For patients treated with BV-DTIC, the most common TEAEs were peripheral sensory neuropathy (experienced by 77%), constipation (45%), fatigue (45%), and nausea (41%) (Table 3). Seven patients (32%) experienced a TEAE that resulted in dose delay. Grade ≥3 TEAEs occurred in 10 patients (45%) treated with BV-DTIC. The most common grade ≥3 TEAEs were peripheral sensory neuropathy (27%) and neutropenia (9%). Treatment-emergent serious AEs (TESAEs) occurred in 18% of patients treated with BV-DTIC. The most common TESAEs were clostridium difficile colitis, hemiparesis, hypotension, and urinary tract infection (all experienced by 5% each). At the data cutoff date (7 April 2023), 11 patients (50%) discontinued treatment because of a TEAE (peripheral sensory neuropathy [n = 8], asthenia [n = 1], hypotension [n = 1], and noncardiac chest pain [n = 1]). Ten patients (46%) treated with BV-DTIC had posttreatment therapy. The subsequent cancer-related therapies for patients treated with BV-DTIC are summarized in supplemental Table 6.

TEAEs occurring in 10% or more of patients in either part B (BV-DTIC) or part D (BV-nivolumab) (full analysis set)

| Preferred term . | Part B (n = 22), n (%) . | Part D (n = 21), n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with any event | 22 (100) | 21 (100) |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 17 (77) | 10 (48) |

| Constipation | 10 (45) | 10 (48) |

| Fatigue | 10 (45) | 16 (76) |

| Nausea | 9 (41) | 10 (48) |

| Arthralgia | 7 (32) | 7 (33) |

| Chills | 0 | 7 (33) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (27) | 10 (48) |

| Edema peripheral | 6 (27) | 3 (14) |

| Productive cough | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Pruritus | 6 (27) | 3 (14) |

| Decreased appetite | 5 (23) | 7 (33) |

| Infusion-related infection | 0 | 7 (33) |

| Dyspnea | 5 (23) | 0 |

| Fall | 5 (23) | 0 |

| Headache | 5 (23) | 4 (19) |

| Insomnia | 3 (14) | 4 (19) |

| Rash | 5 (23) | 3 (14) |

| Weight decreased | 5 (23) | 4 (19) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Alopecia | 4 (18) | 3 (14) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Hyperglycemia | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Hypokalemia | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Cough | 4 (18) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 4 (18) | 5 (24) |

| Dry skin | 4 (18) | 4 (19) |

| Epistaxis | 4 (18) | 0 |

| Muscular weakness | 4 (18) | 2 (10) |

| Neck pain | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Pain | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Paresthesia | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Pyrexia | 4 (18) | 7 (33) |

| Rash maculopapular | 0 | 6 (29) |

| Lipase increased | 0 | 5 (24) |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (14) | 4 (19) |

| Abdominal discomfort | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Amylase increased | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Anemia | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Back pain | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Dehydration | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Fall | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Hyperkalemia | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Malaise | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Asthenia | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Myalgia | 3 (14) | 4 (19) |

| Oral candidiasis | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Pain in extremity | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Neutropenia | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Night sweats | 3 (14) | 3 (14) |

| Peripheral motor neuropathy | 3 (14) | 5 (24) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 3 (14) | 4 (19) |

| Preferred term . | Part B (n = 22), n (%) . | Part D (n = 21), n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with any event | 22 (100) | 21 (100) |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 17 (77) | 10 (48) |

| Constipation | 10 (45) | 10 (48) |

| Fatigue | 10 (45) | 16 (76) |

| Nausea | 9 (41) | 10 (48) |

| Arthralgia | 7 (32) | 7 (33) |

| Chills | 0 | 7 (33) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (27) | 10 (48) |

| Edema peripheral | 6 (27) | 3 (14) |

| Productive cough | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Pruritus | 6 (27) | 3 (14) |

| Decreased appetite | 5 (23) | 7 (33) |

| Infusion-related infection | 0 | 7 (33) |

| Dyspnea | 5 (23) | 0 |

| Fall | 5 (23) | 0 |

| Headache | 5 (23) | 4 (19) |

| Insomnia | 3 (14) | 4 (19) |

| Rash | 5 (23) | 3 (14) |

| Weight decreased | 5 (23) | 4 (19) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Alopecia | 4 (18) | 3 (14) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Hyperglycemia | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Hypokalemia | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Cough | 4 (18) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 4 (18) | 5 (24) |

| Dry skin | 4 (18) | 4 (19) |

| Epistaxis | 4 (18) | 0 |

| Muscular weakness | 4 (18) | 2 (10) |

| Neck pain | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Pain | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Paresthesia | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Pyrexia | 4 (18) | 7 (33) |

| Rash maculopapular | 0 | 6 (29) |

| Lipase increased | 0 | 5 (24) |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (14) | 4 (19) |

| Abdominal discomfort | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Amylase increased | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Anemia | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Back pain | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Dehydration | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Fall | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Hyperkalemia | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Malaise | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Asthenia | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Myalgia | 3 (14) | 4 (19) |

| Oral candidiasis | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Pain in extremity | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Neutropenia | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Night sweats | 3 (14) | 3 (14) |

| Peripheral motor neuropathy | 3 (14) | 5 (24) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (14) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 3 (14) | 4 (19) |

TEAEs are presented and defined as newly occurring (not present at baseline) or worsening after first dose of study drugs. Summaries are sorted by decreasing frequencies in preferred terms. When a patient reported >1 TEAE that was coded to the same preferred term, the patient was counted only once for that specific preferred term.

Of the 22 patients treated with BV-DTIC, 19 (86%) had treatment-emergent PN. Twenty-seven percent had a maximum severity grade of 3. Seven patients (37%) had complete resolution of all PN AEs, and 5 patients (26%) had improvement; 12 patients (63%) had ongoing PN, with 7 patients (37%) and 5 patients (26%) having a maximum severity grade 1 or 2, respectively. The median time to improvement and time to resolution of PN events was 16.0 weeks and 4.6 weeks, respectively. Five patients (23%) enrolled with grade 1 PN at baseline, and the median time to first onset of any PN among those with at least 1 event was 12.3 weeks.

Brentuximab and nivolumab cohort

Twenty-one patients with cHL were enrolled and treated with BV-nivolumab. The median age was 72 years (range, 60-88 years), and most patients were male (71%) with stage III/IV disease (77%) and an ECOG performance status of ≤1 (95%) (Table 1). No patients treated with BV-nivolumab had an ECOG performance status of 2 or 3. One patient (5%) had a missing ECOG performance status. Comprehensive geriatric assessment was completed on all patients at baseline (Table 4). Forty-three percent of patients reported limitations to performing physical functioning tasks, and 38% of patients had ≥3 comorbidities in general or at least 1 comorbidity that significantly interfered with quality of life. Forty-eight percent of patients in the BV-nivolumab cohort took >13.5 seconds to complete the “up and go” test.

Summary of geriatric assessment questionnaire at baseline in part D (BV-nivolumab) (full analysis set)

| Category/variable . | Part D (n = 21), n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Physical functioning, no. of items [10] | |

| Patients who reported “limited a lot” with ≥1 task | 9 (43) |

| Instrumental activities of daily living, no. of items [7] | |

| Patients who are completely dependent in ≥1 task | 1 (5) |

| OARS comorbidity, no. of items [15] | |

| Patients who have 3 or more comorbidities or at least 1 comorbidity, that significantly interferes with QoL | 8 (38) |

| Time to perform “up and go,” no. of items [1] | |

| >13.5 s | 10 (48) |

| Someone to help if you were confined to bed, no. of items [1] | |

| None or a little of the time | 7 (33) |

| Someone to help you with daily chores if you were sick, no. of items [1] | |

| None or a little of the time | 5 (24) |

| Percentage unintentional weight loss in last 6 mo, no. of items [1] | |

| ≥10% | 3 (14) |

| Blessed orientation-memory-concentration test, no. of items [1] | |

| >6 | 3 (14) |

| Category/variable . | Part D (n = 21), n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Physical functioning, no. of items [10] | |

| Patients who reported “limited a lot” with ≥1 task | 9 (43) |

| Instrumental activities of daily living, no. of items [7] | |

| Patients who are completely dependent in ≥1 task | 1 (5) |

| OARS comorbidity, no. of items [15] | |

| Patients who have 3 or more comorbidities or at least 1 comorbidity, that significantly interferes with QoL | 8 (38) |

| Time to perform “up and go,” no. of items [1] | |

| >13.5 s | 10 (48) |

| Someone to help if you were confined to bed, no. of items [1] | |

| None or a little of the time | 7 (33) |

| Someone to help you with daily chores if you were sick, no. of items [1] | |

| None or a little of the time | 5 (24) |

| Percentage unintentional weight loss in last 6 mo, no. of items [1] | |

| ≥10% | 3 (14) |

| Blessed orientation-memory-concentration test, no. of items [1] | |

| >6 | 3 (14) |

Geriatric assessment questionnaire used components from a tool developed and evaluated by Hurria et al.19

No., number; OARS, Older Americans Resources and Services questionnaire; QoL, quality of life.

Additional baseline characteristics are described in supplemental Table 2. The ORR was 86% (95% CI, 63.7-97.0), and the CR rate was 67% in the full analysis set (all treated patients) (supplemental Table 3). The median duration of CR had not been reached (95% CI, 6.6 months-not estimable). With a median follow-up of 51.6 months, mDOR had not been reached in part D (supplemental Figure 1B). The mPFS (Figure 1B) and mOS (Figure 2B) in the full analysis set have not been reached (95% CI for mPFS, 9.4 months-not estimable; 95% CI for mOS, not estimable to not estimable). For the 15 patients treated with BV-nivolumab who then did not receive any subsequent cancer-related therapies, the 5-year OS rate was 78% (95% CI, 46-92), and the median duration of follow-up after first dose was 52.83 months. Of the 2 patients evaluated by PET at cycle 2, both (100%) were PET positive; at cycle 4, a total of 13 of 19 (68%) were PET negative. Of the patients evaluated at EOT, 6 of 7 (86%) were PET negative; similar to part B, PET was not required after CR was reached.

The median number of cycles of BV was 10.0 per patient, and the median number of cycles of nivolumab was 10.0 per patient. No patients received >16 cycles of BV, whereas 1 received >16 cycles of nivolumab. The median duration of treatment for patients treated with BV-nivolumab was 42.9 weeks. The duration of treatment for BV-nivolumab and the associated timepoints of best response is listed in supplemental Table 4. One of 21 patients (5%) treated with BV-nivolumab received G-CSF. One patient (5%) experienced neutropenia.

TEAEs are summarized in supplemental Table 5. For patients treated with BV-nivolumab, the most common TEAEs were fatigue (76%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (48%), constipation (48%), nausea (48%), and diarrhea (48%) (Table 3). Seven patients (33%) experienced a TEAE that resulted in dose delay. Grade ≥3 TEAEs occurred in 16 patients (76%) treated with BV-nivolumab. The most common grade ≥3 TEAEs were increased lipase (24%), motor PN (19%), and sensory PN (19%). TESAEs occurred in 19% of patients treated with BV-nivolumab. The most common TESAEs were nausea and vomiting (both experienced by 14% each). At the data cutoff date (7 April 2023), 5 patients (24%) in part D discontinued treatment because of a TEAE (acute kidney injury [n = 1], hyponatremia [n = 1], peripheral motor neuropathy [n = 1], Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia [n = 1], and pneumonitis [n = 1]). One death due to a TEAE (sepsis) was not considered treatment related. Six patients (29%) treated with BV-nivolumab had posttreatment therapy. The subsequent cancer-related therapies for patients treated with BV-nivolumab are summarized in supplemental Table 6.

Of the 21 patients treated with BV-nivolumab, 13 (62%) had treatment-emergent PN. Thirty-eight percent had a maximum severity grade of 3. Four patients (31%) had complete resolution of all PN AEs, and 5 patients (38%) had improvement; 9 patients (69%) had ongoing PN with 2 patients (15%), 6 patients (46%), and 1 patient (8%) having a maximum severity of grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The median time to improvement and time to resolution of PN events was 13.9 weeks and 14.2 weeks, respectively. Three patients (14%) enrolled with grade 1 PN at baseline, and the median time to first onset of any PN among those with at least 1 event was 9.4 weeks.

Discussion

Older patients with HL have substantial morbidity and mortality when treated with combination chemotherapy. In the initial cohort of the SGN35-015 trial of BV monotherapy in patients deemed ineligible for conventional chemotherapy, the median age of patients enrolled was 78 years, and 5 patients were aged >85 years. The response rate to treatment was 92%, including a CR rate of 73%.20 However, the mDOR with BV alone was only 9 months, which led to interest in combination approaches.

In this analysis, we provide long-term follow-up of the BV-DTIC combination (part B), showing an mPFS of 47.2 months, supporting the inference that some patients treated with this regimen may go on to be cured, and this regimen is currently endorsed as a treatment option for older patients with advanced-stage HL by established guidelines. Despite the signal of durable responses in some patients, the majority of patients still experienced disease progression, which emphasizes the need for novel regimens.

Checkpoint inhibition is highly active in the treatment of relapsed HL, both as a single agent and in combination with chemotherapy.21-26 A randomized trial comparing pembrolizumab with BV in patients with refractory cHL who have relapsed after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or are ineligible for autologous HSCT showed improved PFS with pembrolizumab.27 These data, along with the complementary and distinct mechanisms of action of BV and checkpoint inhibitors, led to studies of the combination in the relapsed setting. In an early phase trial, the combination of BV-nivolumab was highly active, with >80% of patients responding to treatment, including a CR rate of 62%.28 Long-term follow-up of BV-nivolumab as a first salvage regimen showed durable efficacy and prolonged PFS (especially in patients who proceeded directly to HSCT) without additional late toxicity concerns.13 Similar results were obtained in an early phase study of BV combined with nivolumab, ipilimumab, or both.29 Most recently, preliminary results of the SWOG S1826 trial randomizing patients with advanced-stage cHL to doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (AVD)–BV or AVD-nivolumab were presented, showing a PFS benefit and superior safety profile of the AVD-nivolumab combination.30 Ten percent of patients enrolled in this trial were aged >60 years, and the magnitude of benefit was preserved in this subgroup of patients, providing further enthusiasm for early use of checkpoint blockade in HL.30

Given these favorable results and acceptable safety profile of checkpoint inhibitors in combination with BV and chemotherapy, we now report definitive results of our study combining BV and nivolumab in older patients ineligible for chemotherapy. Despite a high median age, inclusion of patients aged up to 88 years, and frailty demonstrated on comprehensive geriatric assessment, our results compare favorably with our previous single agent and combination studies in older patients incorporating BV. With a median follow-up of almost 4 years, the mDOR and mPFS have not been reached, supporting the inference that some patients treated with this regimen may go on to be cured. Comprehensive geriatric assessments demonstrated similar rates of frailty and geriatric syndromes in BV-nivolumab cohort compared with the BV-DTIC cohort.

Our results are in contrast to the Academic and Community Cancer Research United (ACCRU) study, which also evaluated the BV and nivolumab combination in a similar population (median age, 71.5 years), with most patients having some comorbidities.31 The outcomes of the ACCRU study were inferior to our results. Although the predefined ORR was greater than that in this study at 68%, it was not met. Only 16 of the first 25 patients (64%) achieved a response; however, responding patients demonstrated durability in that trial. Importantly, patients in the ACCRU study only received up to 8 cycles of therapy vs up to 16 cycles in this study, which may partially explain the lower ORR than that of our longer treatment program.31 Moreover, robust prospective geriatric assessments were not reported in the ACCRU trial, making cross-trial comparisons challenging. These geriatric fitness markers correlate more strongly with patient outcomes in HL than with performance status and are an evolving standard to assess the fitness of older patients for chemotherapy treatment.32

Limitations of our study include the small numbers of patients from underrepresented backgrounds, broad eligibility criteria, and single-arm design. Moreover, the small sample size results in wide CIs, and the study was not adequately powered to statistically compare the 2 regimens. However, the high median age and documented comorbidities of the enrolled patients and the long-term follow-up provide confidence of the exportability of the results. The rate of neuropathy is in keeping with prior experience with BV in this patient population. For BV-DTIC, 17 patients (77%) experienced peripheral sensory neuropathy, whereas for BV-nivolumab, 10 patients (48%) experienced peripheral sensory neuropathy. In addition, 8 patients (36%) treated with BV-DTIC discontinued because of neuropathy, but only 1 patient (5%) treated with BV-nivolumab discontinued because of neuropathy. Future studies may explore a limited number of BV cycles and prolonged checkpoint inhibition as a means to abrogate this toxicity and maintain the observed high level of efficacy.

Subsequent therapy in our study was not protocol defined and was at the discretion of the treating physician. A small number of patients had improved performance status after induction therapy and received aggressive salvage approaches. However, <20% of patients in both cohorts received subsequent curative-intent therapy, emphasizing the frailty of the patients in our study. The heterogeneous approaches for subsequent therapy used for these patients demonstrate the lack of a clear standard and emphasize a need for prospective studies dedicated to older patient populations in this setting.

Although other more aggressive chemotherapy-containing regimens have demonstrated greater efficacy in selected patients who can tolerate them,3,30 our study demonstrates tolerable safety and promising efficacy of the combination of BV and nivolumab in the larger population of older patients with cHL with substantial comorbidities. Unlike previous single-agent studies, some responses appear to be durable across cohorts. In fact, many patients in both cohorts who did not receive any subsequent therapy had durable CRs with no further therapy. Although this study was not powered to be comparative, mPFS was numerically greater with the BV-nivolumab combination than with BV-DTIC, now with almost 4 years of follow-up. The safety profile was consistent with previous experiences of BV and nivolumab as monotherapies. If our results are validated in larger studies, a future precision approach to the treatment of older patients with cHL may include baseline geriatric assessment, with fit patients receiving chemotherapy-based approaches similar to younger patients and unfit/frail patients receiving the BV-nivolumab regimen, given our observed durable CRs in a subset of these patients.

Acknowledgments

Assistance in medical writing was provided by Amr Y. Eissa of ICG Medical, Inc (San Jose, CA).

This study was funded by Seagen Inc in accordance with good publication practice guidelines.

Authorship

Contribution: J.W.F., R. Bordoni, D.P.-D., T.L., J.G., R. Boccia, V.J.M.C., A.A., and C.A.Y. contributed to the acquisition of the data; A.M. and J.L. accessed and verified the data; J.W.F. wrote the manuscript; T.L., R. Boccia, A.M., J.L., A.A., and C.A.Y. critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R. Bordoni served on advisory boards for Maritz Global Events Inc, OncoCyte, Sanofi US, MJH Events, and Targeted Oncology; served on speakers’ bureaus for Guardant Health, NeoGenomics, AstraZeneca, and Janssen Biotech; and received honoraria from APOS and Cardinal Summit. J.G. served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and Genmab; is an employee of and serves on a corporate board for Blue Ridge Cancer Care; served as a consultant for Ontada and Amgen; served on a speakers’ bureau for G1 Therapeutics; received travel expenses from Ontada and G1 Therapeutics. R. Boccia served on advisory boards for AbbVie, Genmab, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cellectar Biosciences, and DSI; served as a consultant for Cellectar Biosciences; received honoraria from AbbVie, Janssen Biotech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, BeiGene, and Sanofi US; received research funding from Genmab, AbbVie, Amgen, and DSI; and served on speakers’ bureaus for AbbVie, Janssen Biotech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, BeiGene, and Sanofi US. V.J.M.C. served as a consultant and on the safety monitoring committee for CanBas Co Ltd. A.M. and J.L. are employees of and have equity ownership in Seagen Inc. C.A.Y. served as a consultant for Seagen Inc; received research funding from Seagen Inc, Incyte, AstraZeneca, Lilly, and Karyopharm Therapeutics; and served on speaker’s bureaus for BeiGene and Lilly. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.M. is Bristol Myers Squibb, Seattle, WA.

Correspondence: Jonathan W. Friedberg, Wilmot Cancer Institute, University of Rochester, 601 Elmwood Ave, Box 704, Rochester, NY 14642; email: jonathan_friedberg@urmc.rochester.edu.

References

Author notes

Deidentified patient-level trial data that underlie the results reported in this publication will be made available on a case-by-case basis to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. Additional documentation may also be made available. Data availability will begin after approval of the qualified request and end 30 days after receipt of data sets. All requests can be submitted to CTDR@seagen.com and will be reviewed by an internal review committee. Please note that the data sharing policy of this clinical study's sponsor, Seagen Inc, requires all requests for clinical trial data be reviewed to determine the qualification of the specific request. This policy is available at https://www.seagen.com/healthcare-professionals/clinical-data-requests and is aligned with BIO's Principles on Clinical Trial Data Sharing (available at https://www.bio.org/blogs/principles-clinical-trial-data-sharing-reaffirm-commitment).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal