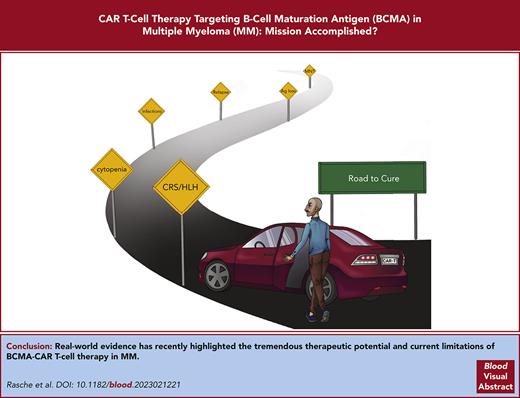

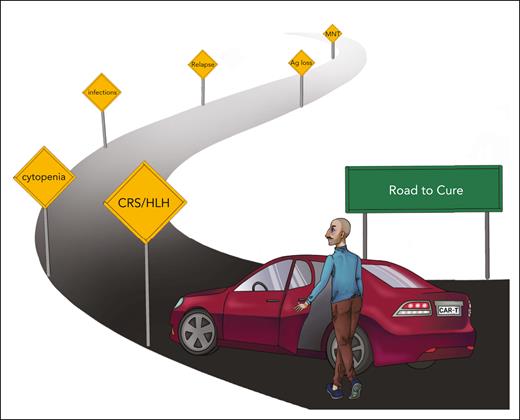

Visual Abstract

B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells are the most potent treatment against multiple myeloma (MM). Here, we review the increasing body of clinical and correlative preclinical data that support their inclusion into firstline therapy and sequencing before T-cell–engaging antibodies. The ambition to cure MM with (BCMA-)CAR T cells is informed by genomic and phenotypic analysis that assess BCMA expression for patient stratification and monitoring, steadily improving early diagnosis and management of side effects, and advances in rapid, scalable CAR T-cell manufacturing to improve access.

Real-world data with BCMA CAR T cells

The approval of 2 B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell products, idecabtagen vicleucel (ide-cel) and ciltacabtagen autoleucel (cilta-cel), by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2021 and 2022, respectively, manifested a new era of cellular immunotherapy in multiple myeloma (MM). Over the past ∼5 years, the field has recognized the enthusiastic reports of investigators who were engaged in the clinical trials that led to these approvals. Recently, an increasing body of data with longer-term clinical follow-up, correlative research, and real-world evidence has added a broader perspective and highlighted the tremendous therapeutic potential and current limitations of BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in MM (Table 1).

MM cure with CAR T-cell therapy: key challenges and potential solutions

| Primary resistance | Use CAR T-cell therapy in early (preferably the first) treatment line and avoid prior immunotherapy-based mode of action |

| Secondary resistance (here, antigen loss) | No prior therapy against same target antigen Dual antigen targeting |

| Pharmacokinetic: poor CAR T-cell engraftment/persistence | May not be required for all CAR T-cell products Use CAR T-cell therapy in early treatment line (or at least collect T cells early) Select memory/naive T-cell subpopulations Perform genetic engineering with transcription factors that enhance T-cell performance |

| Treatment strategy: sequencing of immunotherapy (mode of action and antigen) | Use CAR T cells before bsAbs Perform whole genome sequencing to determine heterozygous and biallelic loss and quantitative analysis to determine antigen density on MM cells and select the mode of action/product |

| Toxicity: CRS/ICANS/neurologic | Vigilant monitoring and proactive therapy Determine minimal effective CAR T-cell dose required |

| Availability: long vein-to-vein time | Use rapid CAR T-cell manufacturing protocol Fresh-in/fresh-out noncryopreserved CAR T-cell product Implement point-of-care manufacturing |

| Access: limited patient access | Reduce cost, for example, with rapid, virus-free, automated CAR T-cell manufacturing Evaluate alternative reimbursement concepts (performance-based, staggered payments) |

| Primary resistance | Use CAR T-cell therapy in early (preferably the first) treatment line and avoid prior immunotherapy-based mode of action |

| Secondary resistance (here, antigen loss) | No prior therapy against same target antigen Dual antigen targeting |

| Pharmacokinetic: poor CAR T-cell engraftment/persistence | May not be required for all CAR T-cell products Use CAR T-cell therapy in early treatment line (or at least collect T cells early) Select memory/naive T-cell subpopulations Perform genetic engineering with transcription factors that enhance T-cell performance |

| Treatment strategy: sequencing of immunotherapy (mode of action and antigen) | Use CAR T cells before bsAbs Perform whole genome sequencing to determine heterozygous and biallelic loss and quantitative analysis to determine antigen density on MM cells and select the mode of action/product |

| Toxicity: CRS/ICANS/neurologic | Vigilant monitoring and proactive therapy Determine minimal effective CAR T-cell dose required |

| Availability: long vein-to-vein time | Use rapid CAR T-cell manufacturing protocol Fresh-in/fresh-out noncryopreserved CAR T-cell product Implement point-of-care manufacturing |

| Access: limited patient access | Reduce cost, for example, with rapid, virus-free, automated CAR T-cell manufacturing Evaluate alternative reimbursement concepts (performance-based, staggered payments) |

At present, a key question is the optimal sequence of CAR T cells and other anti-MM therapies, in particular, T-cell–engaging bispecific antibodies (bsAbs). The objective is to unfold a maximum therapeutic effect that requires T cells that are not terminally exhausted and MM cells that have not been edited to diminish or loose target antigen expression. Preliminary findings indicate that administering cilta-cel to patients who have received prior anti-BCMA bsAbs (n = 7) resulted in an overall response rate (ORR) of 57.1% and a progression-free survival (PFS) of 5.3 months, whereas BCMA-naive patients showed an ORR of 98% and a median PFS of not reached.1 In a retrospective real-world study from the United States, the authors included 196 patients who underwent apheresis for ide-cel.2 Patients were heavily pretreated, and only a minority would have satisfied the inclusion criteria of the KarMMa pivotal trial. PFS was 8.5 months compared with 11.3 months in the KarMMa pivotal trial (optimal dose group),3 and nonrelapse mortality was 5%. Prior BCMA-directed therapy and bsAbs, in particular,4 were associated with inferior outcome of BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in a multivariable analysis (median PFS, 3.2 vs 9 months). These data suggest that prior therapy with 1 of the 2 approved BCMA-directed bsAbs, teclistamab5 and elranatamab,6 has a negative impact on the efficacy of BCMA CAR T cells and that the sequence of bsAbs followed by CAR T cells is suboptimal. In contrast, using bsAbs after CAR T-cell therapy has only slightly reduced ORR at this point, considering the small number of patients.7

Patient selection for BCMA CAR T-cell therapy

Because of the availability and relatively easy access to bsAbs, patient and product selection for CAR T-cell therapy remains challenging,8 but there has lately been a steep learning curve. One example is that frailty does not constitute a barrier for CAR T-cell therapy if organ function is adequate.9 Indeed, there are several ongoing trials that evaluate BCMA CAR T cells for patients who are ineligible for an autologous transplant (eg, CARTITUDE-5 [NCT04923893]). A recent study even suggested that CAR T-cell therapy was feasible for patients who are on hemodialysis.10 In contrast, high-risk features such as a Revised International Staging System (R-ISS) score of 3 and extramedullary disease remain poor prognostic factors for CAR T-cell therapy in MM.3,11 As a consequence, patients with highly proliferative relapsed/refractory (R/R) MM may not be good candidates for CAR T-cell therapy without an effective bridging and/or debulking therapy. This is especially true for situations in which the vein-to-vein (ie, the leukapheresis-to-CAR T-cell infusion) time exceeds 6 to 8 weeks, which renders disease control for these patients challenging. A notable rate of manufacturing failures and out-of-specification CAR T-cell products add to this issue. A new wave of improved manufacturing schemes for CAR T cells with very short ex vivo culture and virus-free fresh-in/fresh-out manufacturing accomplishes vein-to-vein time periods of 2 to 3 weeks or less, and data from clinical trials with these “fast” CAR T-cell products are eagerly awaited (NCT05172596, NCT04935580, NCT04394650, and NCT0449933912). Allogeneic CAR T cells can be available as off-the-shelf products, but efficacy in pilot clinical trials was rather disappointing and inferior to autologous CAR T cells, likely because of immunogenicity resulting from HLA-disparity and genotoxicity resulting from gene editing.13

Acute and chronic toxicity of BCMA CAR T cells

With an increasing number of patients receiving BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, additional insights into acute and chronic toxicity and strategies for their clinical management have been derived. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) is seen in up to 80% of patients with MM who receive CAR T-cell therapy14 but has lost its “fear factor” because refined algorithms for diagnosis and treatment have been established15 and because there is increasing experience, especially at “high-volume” CAR T-cell centers. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a rare but potentially fatal complication after BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, if not adequately managed, with rapidly rising ferritin as a key laboratory finding.16,17 Sarcoidosis-like flare up is another rare condition related to CRS.18,19 A common challenge after BCMA CAR T-cell therapy in MM are infections. There is a well-documented notion of disease-related immunosuppression and the ensuing susceptibility of patients with MM to infections.20 The lymphodepleting conditioning before CAR T-cell infusion, on-target recognition of B cells and plasma cells, and bone marrow inflammation during CRS add to the quantitative and qualitative defect of the immune system. At the American Society of Hematology 2022 conference, Shambavi et al reported that more than one-third of patients have not recovered serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) and peripheral blood T-cell and B-cell counts at 2 years after CAR T-cell therapy, even though they were in complete remission from MM.21 Performing vaccinations before CAR T-cell therapy and IV Ig substitution can aid in preventing infections.22,23

In our view, the most troublesome side effect after BCMA CAR T-cell therapy is multilineage cytopenia.24 In many patients, cytopenia has a biphasic course with a first nadir early after CAR T-cell infusion (mainly due to lymphodepletion) and a second nadir ∼1 month after CAR T-cell infusion (mainly due to on-target reactivity and inflammation). As a consequence, some patients remain dependent on blood transfusions or experience severe infections, which negates the benefit of having a treatment-free interval from MM. Recently, Rejeski et al presented a scoring system, CAR-HEMATOTOX, to assess the risk for prolonged severe neutropenia and severe infections in patients with R/RMM who receive BCMA CAR T-cell therapy.25 In addition to growth factor support, an autologous stem cell boost ought to be evaluated in patients with prolonged cytopenia.26,27

Neurotoxicity after BCMA-directed immunotherapy remains mechanistically poorly understood. In contrast to CD19-CAR T cells, immune effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome is uncommon after BCMA CAR T-cell therapy. However, several neuropathologic adverse events add up to an incidence of ∼20% in patients who receive BCMA CAR T cells. These include headache, tremor, mild aphasia, altered mental status with impaired attention and confusion, apraxia, and lethargy. Less common are Guillain-Barre–like syndrome, Bell paresis, and other cranial nerve palsies, which can be mild to life-threatening. A puzzling side effect are movement and neurocognitive treatment-emergent adverse events (MNT), which has been reported in ∼5% of patients who received cilta-cel.28 A recent case study reported weak BCMA expression in the basal ganglia and caudate nucleus in a patient who presented with Parkinson-like symptoms and eventually deceased.29 Patients with high tumor burden and early neurotoxicity are at risk of MNT at a later time point.28 In clinical practice, reducing MM burden through an effective bridging therapy, vigilant monitoring, and treatment of CRS and neurological symptoms has substantially reduced the rate of late neurotoxicity.28 A recent case report suggests cyclophosphamide may be an effective treatment for MNT.30 We would like to point out, however, that overall, nonrelapse mortality was <5% in clinical trials and between 5% and 9% in real-world studies with BCMA CAR T cells,2,3,11,31 which is not higher than with conventional chemotherapy in the lateline R/R MM setting.32-34

Emerging challenge: relapse after BCMA CAR T cells in late lines of therapy

There is a consensus in the field that BCMA CAR T-cell therapy is the most potent anti-MM therapy that has ever been introduced into the clinic.11 Still, the majority of patients ultimately experience relapse and at the time of relapse, MM cells have frequently acquired changes in target antigen expression. Salvage therapies with CAR T cells and bsAbs that are directed against alternative antigens such as GPRC5D,35,36 FcRH5,37 and SLAMF712,38 showed promising activity in preclinical and early clinical trials. MCARH109, an anti-GPRC5D CAR T-cell product achieved an ORR of ∼70% in patients with R/R MM, regardless of whether they had received prior BCMA-directed therapies.35

BCMA downmodulation and loss is a key mechanism of MM escape from the selective pressure of CAR T cells and bsAbs. We and others have described a number of genomic aberrations that result in BCMA loss such as homozygous deletion,39,40 deletion and mutation,41 and, most recently, a single nucleotide variant disrupting the binding site of teclistamab and elranatamab.42 This single nucleotide variant was detected as a germ line variant in a patient who was primary refractory to ide-cel. Similarly, antigen loss after GPRC5D-CAR T-cell therapy and bsAbs seems to be a common mechanism of resistance.35,40,42 A systematic analysis on the frequency of antigen loss for the panel of candidate target antigens in MM has yet to be performed. Another focus of ongoing research projects is to determine the threshold in BCMA antigen density that is required for MM cell recognition and elimination by distinct CAR T-cell products and bsAbs. In previous work, we have shown that this threshold can be in the range of few 100 CD19 molecules for an optimized CD19-CAR, and correlative clinical data support the notion that CD19 expression above a certain threshold is associated with a higher likelihood of achieving and maintaining remission from lymphoma.43,44 Therefore, we believe that novel diagnostics tools such as whole genome sequencing and single-molecule–sensitive microscopy ought to be implemented into clinical pathology workup for MM to aid in patient stratification and monitoring.

Elucidating additional mechanisms of effective therapy and relapse will inform the refinement of CAR T cells and bsAb and their optimal clinical use. Lin et al reported correlative data from the KarMMa trial highlighting greater CAR T-cell expansion in responding patients compared with patients who were nonresponding.45 Interestingly, a high percentage of naive and early memory CD4 T cells in the leukapheresis material correlated with clinical CAR T-cell expansion and response. These data encourage efforts to augment CAR T-cell performance, for example, through expression of transcription factors that support engraftment, in vivo expansion, and longevity.46,47 The MM microenvironment affects T-cell migration and entry into plasma cell tumors. Robinson et al revealed intralesional and spatial heterogeneity in MM with coexistence of T-cell–rich and T-cell–free microregions potentially regulated by agonistic signals and CD2-CD58 interaction.48 Alterations in T-cell repertoire and macrophage content were recently described in intramedullary lesions49 and reinforced the growing interest in modulating the MM microenvironment in favor of CAR T-cell performance.

Emerging opportunity: myeloma cure with CAR T cells in early lines of therapy?

Recently, 2 randomized trials reported the outcomes of BCMA CAR T-cell therapy vs standard therapy in early treatment lines. The KarMMa-3 trial randomized patients with R/R MM who were daratumumab refractory (the majority were also immunomodulatory imide drug refractory) with 2 to 4 prior therapies to receive ide-cel or standard therapy. At a median follow-up of 18.6 months, the median PFS was 13.3 months in the ide-cel group vs 4.4 months in the standard-therapy group.50 In CARTITUDE-4, lenalidomide-refractory patients with MM with 1 to 3 prior lines of therapy were randomized to cilta-cel or standard therapy. At a median follow-up of 15.9 months, the median PFS was not reached in the cilta-cel group vs 11.8 months in the standard-therapy arm.51 Therefore, we are convinced that BCMA CAR T-cell therapy should and will become the new cornerstone of frontline therapy in MM, with the potential to cure a substantial fraction of patients (Figure 1). Several clinical trials that evaluate BCMA CAR T cells as well as bsAbs in frontline therapy are currently ongoing and tackle induction (eg, NCT05695508), consolidation (eg, NCT05257083), and maintenance (NCT05243797) in firstline therapy.

Potential for MM cure with CAR T-cell therapy in early treatment lines. Currently, CAR T-cell therapy is used in advanced disease settings. The benefit for patients is diminished by manufacturing failure/long vein-to-vein time periods, a high rate of (secondary) resistance that leads to relapse. Therefore, only a minority of patients remains in remission long term. In the future, CAR T-cell therapy ought to be implemented early in the disease course, which, we anticipate, will reduce the percentage of patients who are “lost” because of manufacturing failure or primary and secondary resistance and will lead to a fraction of patients who are long-term survivors after MM.

Potential for MM cure with CAR T-cell therapy in early treatment lines. Currently, CAR T-cell therapy is used in advanced disease settings. The benefit for patients is diminished by manufacturing failure/long vein-to-vein time periods, a high rate of (secondary) resistance that leads to relapse. Therefore, only a minority of patients remains in remission long term. In the future, CAR T-cell therapy ought to be implemented early in the disease course, which, we anticipate, will reduce the percentage of patients who are “lost” because of manufacturing failure or primary and secondary resistance and will lead to a fraction of patients who are long-term survivors after MM.

A major objective still to be accomplished is to broaden and facilitate patient access to CAR T-cell therapy. At the time of writing this article, ide-cel was available and reimbursed in 5 countries (United States, France, Switzerland, Japan, and Germany) and cilta-cel only in 2 countries (United States and Germany). The advancement of scalable, virus-free, automated manufacturing will increase the number of available products. Point-of-care manufacturing is another key leverage to shorten the vein-to-vein time, reduce cost, and engage clinical sites in work flow and valorization. Finally, revisiting the one-off reimbursement scheme in favor of a baseline payment plus performance-based installments can aid in acceptance by health care payers and enable patient access in countries that are blank on the CAR T-cell world map.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emilia Stanojkovska and Maik Luu for their assistance in preparing the figure.

The authors acknowledge the support of the Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation (L.R., M.H., H.E.). The authors were supported by the European Union’s innovation program under grant agreement numbers 101016909 (AIDPATH) (M.H.) and 754658 (CARAMBA) (M.H., H.E.), the EURA-NET-TransCan Network (SmartCAR-T) (M.H.), and the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement numbers 853988 (imSAVAR) (M.H., H.E.) and 116026 (T2EVOLVE) (M.H., H.E.). This Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program and EFPIA. The authors have been supported by the patient advocacy group Hilfe im Kampf gegen den Krebs e.V., Würzburg, Germany, and Forschung hilft Stiftung zur Förderung der Krebsforschung an der Universität Würzburg. Furthermore, the authors were supported by German Cancer Aid (Stiftung Deutsche Krebshilfe) grant 70114707 (AvantCAR.de) (M.H.) and the Mildred-Scheel-Nachwuchszentrum program (L.R.). The authors have been supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Transregio (TRR) 221, subproject A03 [M.H., H.E.] and TRR 338, subproject A02 [M.H.]) and the Bavarian Center for Cancer Research (Bayerisches Zentrum für Krebsforschung, Leuchtturm Immuntherapie [M.H., H.E.]). The authors acknowledge support from the German Ministry for Science and Education (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung) grants 13N15986 (IMAGINE) (M.H. and H.E.), 01EN2306A (ROR2 CART) (M.H., H.E.), and 031L0311B (TissueNet) (L.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: L.R., M.H., and H.E. wrote and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.R. participated in scientific advisory boards for Janssen, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi and has received research support from SkylineDx. M.H. participated in scientific advisory boards for Janssen and Celgene/BMS; received research support from Celgene/BMS and Miltenyi Biotec; received honoraria from Janssen, Celgene/BMS, Kite/Gilead, Novartis, and Lymphoma/MyelomaHub; is listed as an inventor on patent applications and granted patents related to CAR technologies that have been filed by the University of Würzburg and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA, and that has been, in part, licensed to industry; and is a cofounder and equity owner of the biotech company T-CURX GmbH, Würzburg, Germany. H.E. participated scientific advisory board for Janssen, Celgene/BMS, Amgen, Novartis, and Takeda; received research support from Janssen, Celgene/BMS, Amgen, and Novartis; and received honoraria from Janssen, Celgene/BMS, Amgen, Novartis, and Takeda.

Correspondence: Hermann Einsele, Universitätsklinikum Würzburg, Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik II, Oberdürrbacherstr 6, N/A 97080 Würzburg, Germany; email: einsele_h@ukw.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal