In this issue of Blood, Huber et al present a 3-year follow-up analysis of the phase 2 CLL2-GIVe trial, demonstrating continued robust clinical activity of the triplet combination of obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax in previously untreated patients with del(17p) and/or TP53-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1

Triplet therapy for CLL involving the combined use of B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling inhibitor, BCL2 inhibitor, and CD20-targeting monoclonal antibodies represents an emerging therapeutic innovation. Simultaneously targeting multiple CLL dependencies could theoretically limit the selection of therapy-resistant subclones, which could translate into deeper remissions that permit safe treatment discontinuation. In genetically unselected treatment-naïve patients, the triplet combination comprising ibrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab (IVO, also known as GIVe) previously demonstrated an undetectable measurable residual disease (MRD) (<10−4) rate of 67% following 14 cycles,2 whereas acalabrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab (AVO) produced MRD negativity (<10−4) in 86% of patients after 15 cycles in an earlier phase 2 study.3

TP53 alterations confer genomic instability and are associated with inferior long-term outcomes even with targeted therapy.4 Accordingly, the rationale for the use of triplet therapeutic combination is arguably stronger in the setting of high-risk CLL harboring TP53 deletion (ie, del[17p]) and/or mutation, and therefore warrants investigation specifically within this genetic subgroup. In this regard, the CLL2-GIVe trial, which enrolled 41 previously untreated patients with TP53-deleted/mutated CLL on a single-arm IVO regimen, provides instructive insight into the clinical activity of this triplet regimen for such a patient population. Specifically, patients enrolled in this study were treated with 6 cycles of IVO induction followed by 6 cycles of ibrutinib and venetoclax as consolidation and thereafter with 3 further cycles of ibrutinib. The subsequent duration of maintenance therapy was intended to be MRD-guided with ibrutinib monotherapy continued until the attainment of an MRD-negative complete response (CR/CRi). An interim report last year provided early evidence of its efficacy with MRD-negative (<10−4) rates of 78% and 66% in the peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM), respectively, at 15 months and a notable 95% 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).5

Herein, the investigators present an updated analysis of this important trial. With a median follow-up of 38 months, the outcome data remain highly encouraging. At final restaging at cycle 15, the overall response (OR) rate was 100%, and the CR/CRi rate was 59%, with a PB MRD-negative rate of 44% at 36 months. The 36-month PFS and OS were 80% and 93%, respectively, and median PFS and OS were not reached. In comparison, within the expansion cohort of the AVO trial that likewise enrolled exclusively treatment-naïve patients with TP53-aberrant CLL, the OR and CR rates in the 29 evaluable patients were 100% and 52%, respectively, at a median follow-up of 35 months, with 86% of patients achieving undetectable MRD (<10−4) in PB and BM at 15 months.6 Triplet combinations involving Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi), venetoclax, and obinutuzumab thus appear highly active in the setting of previously untreated TP53-aberrant CLL.

Currently, triplet combination therapies for CLL remain investigational rather than the standard of care. Important questions to be addressed include their efficacy and toxicity relative to single or dual targeted agents and whether such therapeutic combinations are desirable for all patients or only a select group of young and fit individuals. The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected patients with hematologic malignancies including CLL and brings to light the importance of considering potential infectious complications of CLL treatment. The current study was initiated in the prepandemic era, and although cytopenia was common, there were few reported treatment-limiting toxicities. However, attention needs to be paid to ascertain whether triplet therapies are more toxic than dual therapy or monotherapy in the postpandemic setting. In terms of comparative efficacy among previously untreated patients without TP53 alterations, IVO demonstrated superiority over venetoclax-rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy in the GAIA-CLL13 trial, but clear difference in MRD-negative rates between IVO and venetoclax-obinutuzumab was not apparent.7 Similarly, in older patients with treatment-naïve CLL, the Alliance A041702 trial thus far failed to demonstrate superiority of IVO over ibrutinib-obinutuzumab.8 Within the specific context of TP53-deleted/mutated CLL, results from the ongoing phase 3 CLL16 trial comparing AVO vs obinutuzumab-venetoclax will be eagerly awaited.

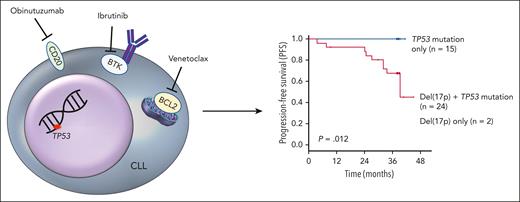

Although exploratory by nature owing to the limited sample size, correlative work in the current study revealed significantly inferior PFS in patients harboring both TP53 mutation and del(17p) compared with those with a sole TP53 mutation (see figure). Biallelic TP53 loss arising from deletion of 1 copy of the TP53 gene and inactivating mutation in the other results in the complete loss of p53-mediated cell cycle control and apoptosis in response to cellular stress and oncogenic activity.9 This could render CLL subpopulations harboring biallelic TP53 loss more genetically unstable with heightened risk of acquiring additional resistance mutations during treatment, as well as increased clonal repopulation propensity due to higher CLL proliferation rate upon subsequent treatment discontinuation.10 The former may manifest in a slower rate of CLL depletion during treatment and ultimately shallower remissions, whereas the latter may manifest in a shorter MRD doubling time upon stopping treatment.

Three-year PFS data from the CLL2-GIVe trial stratified by TP53 status. Patients with TP53 mutation only (n = 15, blue curve) displayed superior PFS with the triplet combination of obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax compared with patients with both del(17p) and TP53 mutation (biallelic TP53 loss, n = 24) or del(17p) alone (n = 2).

Three-year PFS data from the CLL2-GIVe trial stratified by TP53 status. Patients with TP53 mutation only (n = 15, blue curve) displayed superior PFS with the triplet combination of obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax compared with patients with both del(17p) and TP53 mutation (biallelic TP53 loss, n = 24) or del(17p) alone (n = 2).

This raises 2 important implications. First, maintenance therapy may be needed for patients with both TP53 mutation and del(17p), and in this respect, maintenance with ibrutinib monotherapy following completion of the triplet regimen appeared effective in suppressing subclonal outgrowth, with relapses being witnessed exclusively among patients without maintenance therapy. On the other hand, sole TP53-mutated CLL with mutated IGHV showed no progression events, and hence time-limited therapy could suffice. Second, if TP53-null clones are indeed associated with accelerated regrowth kinetics, this would suggest that remissions deeper than the conventional 10−4 MRD threshold may be necessary for treatment cessation to achieve durable response. More sensitive methods for MRD monitoring (eg, clonoSEQ; 10−6) may assist in guiding treatment duration and preempting the need for re-treatment.

Finally, with noncovalent BTKi and novel BCL2 inhibitors adding to the panoply of CLL treatments, the GIVe regimen of Huber et al may be the first therapeutic triplet for TP53-aberrant CLL but will certainly not be the last. For patients, cautious optimism is the order of the day. Watch this space!

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal