Key Points

aGVHD triggers the generation of CD11b+CD163+ monocytes and TCRαβ+ or TCRγδ+ effector T cells with skin- or gut-homing properties.

Additional CD11b– dendritic subsets and IgM– plasmablasts classify patients with GVHD refractory to MSC-based second-line therapy.

Abstract

Acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) is an immune cell‒driven, potentially lethal complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation affecting diverse organs, including the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. We applied mass cytometry (CyTOF) to dissect circulating myeloid and lymphoid cells in children with severe (grade III-IV) aGVHD treated with immune suppressive drugs alone (first-line therapy) or in combination with mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs; second-line therapy). These results were compared with CyTOF data generated in children who underwent transplantation with no aGVHD or age-matched healthy control participants. Onset of aGVHD was associated with the appearance of CD11b+CD163+ myeloid cells in the blood and accumulation in the skin and GI tract. Distinct T-cell populations, including TCRγδ+ cells, expressing activation markers and chemokine receptors guiding homing to the skin and GI tract were found in the same blood samples. CXCR3+ T cells released inflammation-promoting factors after overnight stimulation. These results indicate that lymphoid and myeloid compartments are triggered at aGVHD onset. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) presumably class switched, plasmablasts, and 2 distinct CD11b– dendritic cell subsets were other prominent immune populations found early during the course of aGVHD in patients refractory to both first- and second-line (MSC-based) therapy. In these nonresponding patients, effector and regulatory T cells with skin- or gut-homing receptors also remained proportionally high over time, whereas their frequencies declined in therapy responders. Our results underscore the additive value of high-dimensional immune cell profiling for clinical response evaluation, which may assist timely decision-making in the management of severe aGVHD.

Introduction

Inflammatory cues, including both sterile damage-associated and pathogen-associated molecular patterns, drive innate and adaptive immune responses, wherein T cells are considered the main effector cells associated with targeted tissue-cell death. This basic concept also applies to acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD), a situation wherein damage to the skin, liver, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and other organ systems is classically attributed to donor T cells responding to inflammation-exposed host cells.1,2 Different replacement rates of skin CD163+ or CD163– (allo)antigen-presenting cells by cells arising from engrafted donor CD34+ stem cells have been reported.3 The transient setting of coexisting donor and host tissue-resident cells (mixed chimerism) early after graft infusion provides an ideal setting for alloimmune T-cell priming.4,5 Next to donor T cells, tissue-resident host T cells and newly generated donor macrophages seem to be additional drivers of aGVHD pathogenesis.6,7 Recruitment of innate and adaptive immune cells of donor origin to the skin and GI tract is likely fueled by commensal and pathogenic bacteria entering the body via epithelial tissues damaged by aGVHD.1 Although the beneficial effect of commensal flora elimination on graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) rates in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has been documented,8,9 more recent studies showed that specific microbial species are associated with increased aGVHD rates10 and that a diverse GI tract microbiome correlates with better transplantation outcomes.11-13 Translocating microbes, or their (metabolic) products, trigger cytokine release by tissue-resident innate immune cells, which promotes the migration of antigen-presenting cells to draining lymph nodes, where they interact with resting T cells.1 Some of these cytokines also promote myelopoiesis. The final step in this inflammatory cascade1,14,15 is the recruitment of immune effector cells that contribute to local inflammation and tissue damage through the release of cytokines and cytotoxic compounds.

Inflammation-driven recruitment of immune cells to GVHD-affected tissues indicates a key role for locally produced chemokines that, upon binding to chemokine receptors like CCR9 and CCR6, regulate their migration to the GI tract16 or the skin. Skin homing is also facilitated by cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA), CCR10, and CCR4.17-19 Interactions among CCL20-CCR6,20 CCL27-CCR10,18 and CXCL10-CXCR321 all seem to be involved in skin aGVHD. Because CXCR3-binding ligands are key immune cell attractants produced at sites displaying interferon (IFN)-γ-induced inflammation, it is conceivable that CXCR3+ T cells are codrivers of aGVHD.

High-dose steroids induce complete resolution of clinical symptoms in about 50% of patients with aGVHD.22-24 Steroid-refractory patients who progress to severe (grade III-IV) aGVHD require second- or third-line immunosuppressive treatment because of the high risk of transplantation-related mortality.23 Bone marrow‒derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are multipotent nonhematopoietic cells with strong immune modulatory and tissue regenerative capacity that can home to sites of injury- or disease-induced inflammation.25,26 Despite currently available clinical data27-31 underlying (conditional) approval of MSC therapy as second-line therapy in some countries, no firm conclusions regarding its efficacy and mechanism of action in the context of aGVHD can be drawn as yet. Nonetheless, we hypothesized that so-called MSC nonresponders (meaning those who do not respond to first-line steroids and second-line steroids combined with MSC therapy) represent a unique study population for the identification of immune correlates specifically associated with progressive, treatment-refractory aGVHD. Herein, we report the results of high-dimensional mass cytometry (CyTOF)‒based profiling32-34 of myeloid and lymphoid cell populations present in retrospectively selected peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) derived from such patients.

Methods

Study design

This CyTOF study cohort comprised 5 different pediatric study groups: (1) healthy control participants, (2) patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD, (3) patients who underwent HSCT and demonstrated aGVHD responsive to steroids, and patients undergoing HSCT who demonstrated steroid-refractory aGVHD being either responsive (4) or nonresponsive (5) to MSC-based second-line therapy. Summarized information of patients and control participants is presented in Table 1. Patient-specific information, including time points of peripheral blood sampling, is presented in supplemental Figure 1 and supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website. Patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD received 1 or 2 infusions of MSC prepared from bone marrow samples of third-party allogeneic donors in addition to first-line GVHD therapy (supplemental Table 1); 10 of 17 MSC recipients were enrolled in an investigator-initiated observational phase 1/2 study (2005-2009).30 Seven patients were treated on compassionate use base (2010-2013). Patient sampling for assessment of immune reconstitution was covered by protocol P01.028 (patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD and patients who underwent HSCT with steroid-responsive aGVHD) and P05.089 (HSCT with steroid-refractory aGVHD either responsive or nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy groups), both approved by the institutional review board of the Leiden University Medical Center. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was provided by the patients’ parents or legal guardians, which was documented in the patients’ medical records.

Characteristics of study participants

| CyTOF study cohort . | Patients who underwent HSCT and demonstrated aGVHD . | No aGVHD . | No HSCT . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (n = 11) . | Steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy group (n = 6) . | Steroid-responsive aGVHD (n = 7) . | HSCT control participants (n = 11) . | Healthy control participants (n = 7) . | |

| Age (y)∗ | 12.5 (1.3-18.1) | 12.6 (1.3-16.9) | 9.9 (2.4-15) | 11.1 (0.3-17.8) | 12.1 (8-18.3) |

| Transplantation period | 2005-2013 | 2005-2013 | 2005-2010 | 2005-2012 | N/A |

| Male sex | 6 (55%) | 4 (67%) | 5 (71%) | 7 (64%) | 5 (71%) |

| HSCT indication | |||||

| Malignant disease | 8 (73%) | 3 (50%) | 5 (71%) | 10 (91%) | N/A |

| Nonmalignant disease | 3 (27%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (29%) | 1 (9%) | |

| Graft type† | |||||

| BM | 8 (73%) | 5 (83%) | 5 (71%) | 9 (82%) | N/A |

| Other | 3 (27%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (29%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Donor type‡ | |||||

| IRD/ORD | 6 (55%) | 2 (33%) | 0 | 6 (54%) | N/A |

| MUD | 5 (45%) | 4 (67%) | 7 (100%) | 5 (45%) | |

| Conditioning regimen§ | |||||

| Bu-Cy based | 5 (45%) | 1 (17%) | 3 (43%) | 6 (55%) | N/A |

| Bu-Flu based | 2 (18%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (14%) | 0 | |

| Other | 4 (36%) | 4 (67%) | 3 (43%) | 5 (45%) | |

| Serotherapy‖ | |||||

| ATG | 3 (27%) | 3 (50%) | 7 (100%) | 4 (36%) | N/A |

| Alemtuzumab | 1 (9%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (9%) | |

| None | 7 (64%) | 3 (50%) | 0 | 6 (55%) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis¶ | |||||

| CsA ± MTX | 8 (73%) | 1 (17%) | 4 (57%) | 9 (82%) | N/A |

| CsA ± MTX + other | 2 (18%) | 2 (33%) | 3 (43%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Other | 0 | 3 (50%) | 0 | 0 | |

| None | 1 (9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| GVHD onset (day + range) | 57 (12-86, 195)∗∗ | 28 (14-62) | 30 (15-89) | N/A | N/A |

| GVHD grade# | |||||

| I | 0 | 0 | 2 (29%) | N/A | N/A |

| II | 0 | 0 | 3 (43%) | ||

| III | 7 (64%) | 2 (33%) | 2 (29%) | ||

| IV | 4 (36%) | 4 (67%) | 0 | ||

| Organ involvement | N/A | N/A | |||

| Skin | |||||

| 0 | 5 (46%) | 0 | 2 (29%) | ||

| 1-2 | 3 (27%) | 2 (33%) | 3 (43%) | ||

| 3-4 | 3 (27%) | 4 (67%) | 2 (23%) | ||

| Liver | |||||

| 0 | 6 (55%) | 4 (67%) | 6 (85%) | ||

| 1-2 | 2 (18%) | 0 | 1 (14%) | ||

| 3-4 | 3 (27%) | 2 (33%) | 0 | ||

| GI tract | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (71%) | ||

| 1-2 | 3 (27%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | ||

| 3-4 | 8 (73%) | 5 (83%) | 2 (29%) | ||

| GVHD treatment†† | |||||

| Steroids | 4 (36%) | 0 | 2 (29%) | N/A | N/A |

| Steroids + other | 7 (64%) | 6 (100%) | 5 (71%) | ||

| No. of MSC infusions | |||||

| 1 | 8 (73%) | 2 (33%) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 3 (27%) | 4 (67%) | |||

| Viral reactivations‡‡ | |||||

| Yes | 8 (73%) | 5 (83%) | 6 (86%) | 6 (55%) | N/A |

| Adenovirus | 1 (9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CMV | 2 (18%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | 2 (18%) | |

| EBV | 4 (36%) | 1 (17%) | 3 (43%) | 3 (27%) | |

| Combination | 1 (9%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (43%) | 1 (9%) | |

| 100% chimerism§§ | 11 (100%) | 4 (67%) | 7 (100%) | 9 (82%) | N/A |

| Alive at d + 365‖‖ | 9 (82%) | 1 (17%) | 7 (100%) | 10 (91%) | N/A |

| CyTOF study cohort . | Patients who underwent HSCT and demonstrated aGVHD . | No aGVHD . | No HSCT . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (n = 11) . | Steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy group (n = 6) . | Steroid-responsive aGVHD (n = 7) . | HSCT control participants (n = 11) . | Healthy control participants (n = 7) . | |

| Age (y)∗ | 12.5 (1.3-18.1) | 12.6 (1.3-16.9) | 9.9 (2.4-15) | 11.1 (0.3-17.8) | 12.1 (8-18.3) |

| Transplantation period | 2005-2013 | 2005-2013 | 2005-2010 | 2005-2012 | N/A |

| Male sex | 6 (55%) | 4 (67%) | 5 (71%) | 7 (64%) | 5 (71%) |

| HSCT indication | |||||

| Malignant disease | 8 (73%) | 3 (50%) | 5 (71%) | 10 (91%) | N/A |

| Nonmalignant disease | 3 (27%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (29%) | 1 (9%) | |

| Graft type† | |||||

| BM | 8 (73%) | 5 (83%) | 5 (71%) | 9 (82%) | N/A |

| Other | 3 (27%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (29%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Donor type‡ | |||||

| IRD/ORD | 6 (55%) | 2 (33%) | 0 | 6 (54%) | N/A |

| MUD | 5 (45%) | 4 (67%) | 7 (100%) | 5 (45%) | |

| Conditioning regimen§ | |||||

| Bu-Cy based | 5 (45%) | 1 (17%) | 3 (43%) | 6 (55%) | N/A |

| Bu-Flu based | 2 (18%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (14%) | 0 | |

| Other | 4 (36%) | 4 (67%) | 3 (43%) | 5 (45%) | |

| Serotherapy‖ | |||||

| ATG | 3 (27%) | 3 (50%) | 7 (100%) | 4 (36%) | N/A |

| Alemtuzumab | 1 (9%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (9%) | |

| None | 7 (64%) | 3 (50%) | 0 | 6 (55%) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis¶ | |||||

| CsA ± MTX | 8 (73%) | 1 (17%) | 4 (57%) | 9 (82%) | N/A |

| CsA ± MTX + other | 2 (18%) | 2 (33%) | 3 (43%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Other | 0 | 3 (50%) | 0 | 0 | |

| None | 1 (9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| GVHD onset (day + range) | 57 (12-86, 195)∗∗ | 28 (14-62) | 30 (15-89) | N/A | N/A |

| GVHD grade# | |||||

| I | 0 | 0 | 2 (29%) | N/A | N/A |

| II | 0 | 0 | 3 (43%) | ||

| III | 7 (64%) | 2 (33%) | 2 (29%) | ||

| IV | 4 (36%) | 4 (67%) | 0 | ||

| Organ involvement | N/A | N/A | |||

| Skin | |||||

| 0 | 5 (46%) | 0 | 2 (29%) | ||

| 1-2 | 3 (27%) | 2 (33%) | 3 (43%) | ||

| 3-4 | 3 (27%) | 4 (67%) | 2 (23%) | ||

| Liver | |||||

| 0 | 6 (55%) | 4 (67%) | 6 (85%) | ||

| 1-2 | 2 (18%) | 0 | 1 (14%) | ||

| 3-4 | 3 (27%) | 2 (33%) | 0 | ||

| GI tract | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (71%) | ||

| 1-2 | 3 (27%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | ||

| 3-4 | 8 (73%) | 5 (83%) | 2 (29%) | ||

| GVHD treatment†† | |||||

| Steroids | 4 (36%) | 0 | 2 (29%) | N/A | N/A |

| Steroids + other | 7 (64%) | 6 (100%) | 5 (71%) | ||

| No. of MSC infusions | |||||

| 1 | 8 (73%) | 2 (33%) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 3 (27%) | 4 (67%) | |||

| Viral reactivations‡‡ | |||||

| Yes | 8 (73%) | 5 (83%) | 6 (86%) | 6 (55%) | N/A |

| Adenovirus | 1 (9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CMV | 2 (18%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | 2 (18%) | |

| EBV | 4 (36%) | 1 (17%) | 3 (43%) | 3 (27%) | |

| Combination | 1 (9%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (43%) | 1 (9%) | |

| 100% chimerism§§ | 11 (100%) | 4 (67%) | 7 (100%) | 9 (82%) | N/A |

| Alive at d + 365‖‖ | 9 (82%) | 1 (17%) | 7 (100%) | 10 (91%) | N/A |

aGVHD, acute graft-versus-host disease; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; BM, bone marrow; Bu, busulfan; CB, cord blood; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CsA, ciclosporin; Cy, cyclophosphamide; CyTOF, mass cytometry; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; Flu, fludarabine; GI, gastrointestinal; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; IRD, identical related donor; MSC, mesenchymal stromal cell; MTX, methotrexate; MUD, matched unrelated donor; ORD, other related donor; N/A, not applicable.

Median age (range) in years at the day of hematopoietic stem cell donation or infusion.

Graft types include BM, CB, or granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized peripheral blood stem cells.

Donor types include MUD (minimal 10/12 matched), IRD, and ORD.

Other agents used are listed in supplemental Table 1.

T-cell-depleting agents include ATG or Campath (anti-CD52).

GVHD prophylactic medication included CsA and MTX. Other agents applied are listed in supplemental Table 1.

GVHD diagnoses were based on both clinical symptoms and histologic evaluation of biopsy samples obtained from affected sites, as reported earlier.1,68 Clinical symptoms of GVHD were scored and included degree of skin rash, total bilirubin levels, and output per day of diarrhea with or without abdominal pain.68 Steroid-refractory aGVHD was defined as either no response at least 7 d after starting a minimum daily dose of 2 mg/kg prednisone, or aGVHD progression of at least 1 grade within 72 h after prednisone-based treatment was initiated.

One patient demonstrated aGVHD at day d + 195 after receiving unselected donor lymphocytes administered at d + 156 for the conversion of a declined percentage of donor chimerism.

Other immune-suppressive drugs applied for GVHD treatment are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Viral reactivations were detected by routine polymerase chain reaction-based monitoring of blood samples collected up to the last PBMC sample (t = 2 or t = 3) included in the study.

Number of patients per group in whom 100% of PBMC (collected at or shortly before t = 1) displayed donor-specific DNA sequence as assessed by short tandem repeat assay.

Causes of death include GVHD, infectious complications, or relapse of the original malignancy, as detailed in supplemental Table 1.

Analysis of mass cytometry data

Details on the preparation and antibody staining of pooled, live, barcoded PBMC samples (5 individual patient samples and 1 control sample) and tissue samples can be found in the supplementary Methods and Data file. After data acquisition, multiplex samples were de-barcoded using a single-cell de-barcoder tool.32 Subsequently, live single cells were selected in FlowJo software version 10 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) by exclusion of calibration beads, dead cells, and doublets (supplemental Figure 2A) before further analysis. No stringent CD45 gating was applied at this stage to avoid excluding cells that express lower levels of CD45. The number of cells after de-barcoding and gating ranged between 2 × 104 and 7 × 105 (supplemental Figure 2B). To determine interexperiment and measurement variability, reference samples stained with antibody panel A and B were analyzed in 2 separate t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plots; the x and y coordinates of each individual sample were used for Jensen-Shannon analysis (supplemental Figure 2E). Jensen-Shannon plots were generated using Matlab version R2016a software. Two datasets each containing ± 31 × 106 cells (stained with antibody panel A or B) from patients and control participants were obtained after de-barcoding and gating for live single cells. To analyze the full dataset without downsampling, each group was initially analyzed separately using hierarchical stochastic neighbor embedding (HSNE) implemented in Cytosplore version 2.3.0.35 Values from all markers were arcsine5 transformed and a selection of markers was used to distinguish 6 major lineage populations in each sample group, as detailed in the supplemental Methods and Data file. Data generated on distinct lineage populations from all sample groups were pooled and analyzed together to compare subcluster frequency within different study groups. Subclusters were generated using the Gaussian-mean-shift method implemented in Cytosplore.

Statistical analysis

Flow cytometry standard (FCS) files from generated clusters were analyzed in R version 3.6.2 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the Cytofast package36 for further downstream analysis and data visualization. In addition, the R workflow from Nowicka et al37 was applied for statistical analysis. Generalized linear mixed models were applied for differences in cell abundance, and linear mixed models were used to evaluate differential marker expression. Detailed descriptions on statistical analysis of the data are found in the supplemental Methods. P values were corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to adjust for multiple comparisons and were considered significant when P < .05. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test before- and after-treatment differences of individual specified clusters.

Results

Profiling myeloid and lymphoid subpopulations in cryopreserved PBMCs

We generated immune profiles on PBMCs derived from 7 healthy control participants, 11 pediatric patients who underwent HSCT and did not demonstrate aGVHD (HSCT control group), and 24 pediatric patients with aGVHD who responded differently to first- or second-line (MSC-based) treatment. This third group included 7 patients responsive to first-line steroids (HSCT with steroid-responsive aGVHD) and 17 patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD who responded differently to MSC-based second-line therapy. The latter group comprised 11 patients in whom aGVHD symptoms resolved completely (HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy) and 6 HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy. Because aGVHD can occur at any given point after donor stem cell infusion, Table 1 shows the median day (plus range) of aGVHD onset. Timing of the first sample selection (t = 1) in relationship to the day of graft infusion and aGVHD onset for each patient is shown in supplemental Figure 1B and supplemental Table 1. Using a multiplex CyTOF staining approach, we identified 9 different immune populations within the overview datasets generated per study group (supplemental Figure 3A-C). Within CD45bright cells, we identified (1) CD4+TCRαβ+ T cells; (2) CD8+TCRαβ+ T cells; (3) TCRγδ+ T cells; (4) CD19+ B cells; and (5) CD11b+ myeloid cells. The CD45dim population contained (6) natural killer (NK) cells, (7) CD123brightCD14–CD11c+ basophils, and (8) CD34+ hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells; (9) CD11b– dendritic cells (DCs), including both CD11b–CD123–BDCA-2–CD11cbright conventional DCs (cDCs) and CD11b–CD123+BDCA-2+CD11c– plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), were found within the myeloid cells and the CD45dim population (supplemental Figure 3B). The frequencies of each major immune population varied per patient subgroup, which may be related to whether serotherapy was part of the GVHD prophylaxis (Table 1) and to variation in time between graft infusion and blood sampling (supplemental Figure 1B; Table 1). In line with other reports,38-40 significantly decreased frequencies of CD4+ T cells were observed in the t = 1 samples of all patient groups who underwent HSCT (supplemental Figure 3D) (P < .001). This corresponded to low absolute cell numbers in the same PBMC samples before cryopreservation (supplemental Figure 4). In contrast, CD14+ myeloid cells were significantly increased at t = 1 in both HSCT control participants (P < .01) and in patients with aGVHD (supplemental Figure 3D) (P < .05). The lowest frequencies of DC (P < .01) or B-cell (P < .05) lineage cells were found in the group of HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy. The latter finding was also in line with total B-cell counts assessed before cryopreservation (supplemental Figure 4). It is well known that B-cell recovery after allogenic HSCT is slow as it may take up to 1 year to reach normal B-cell counts.38-40 Taken together, these results indicate that the composition of the major immune populations detected in our patient cohort reflects the different rates of immune reconstitution after myeloablative HSCT. The results also indicate that cryopreservation did not result in disproportional loss of T-cell populations, B cells, or NK cells.

aGVHD is associated with increased frequencies of CD163+ monocytes

To further dissect the major immune populations present in these samples, we performed second-level analyses yielding 135 unique immune cell subclusters among the major lineage cells (supplemental Figure 5): B-cells (n = 18), NK cells (n = 10), monocytes (n = 12), DCs (n = 11), CD4+ T cells (n = 27), CD8+ T cells (n = 32) and TCRγδ+ T cells (n = 25). We first focused on differentially abundant myeloid cell subclusters that were more prevalent in patients who demonstrated aGVHD (Figure 1A-C). In line with observations in adult aGVHD,7 we observed increased frequencies of circulating HLA-DRdimCD14brightCD163+CD64+ with (Mo-8) or without (Mo-11) CD56 (Figure 1C). A second CD56+ monocyte subcluster, coexpressing the degranulation marker CD107a and CD64, but no CD163 (Mo-12), was found predominantly in patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD. In contrast, patients with aGVHD displayed lower frequencies of CD300e+ classical (Mo-6 and Mo-7) and nonclassical (Mo-2) monocytes. CD163+ cells, presumably macrophages, were also abundantly present in skin and GI tract biopsy samples of patients with severe (progressive) aGVHD (Figure 1D), extending earlier observations in cutaneous aGVHD.7,41 Hence, aGVHD onset is generally associated with increased production and recruitment of monocytes specialized in the recognition of bacteria.

CD163+cells are abundant in PBMC, skin, and GI tract samples of patients with acute GVHD. (A) Hierarchical stochastic neighbor embedding (HSNE)–guided dissection of blood-derived myeloid cells that belong either to the monocyte or DC lineage. (B) Heatmap showing 11 different monocyte subclusters (CD14+CD16– classical, CD14+CD16dim/intermediate, or CD14neg/dimCD16bright nonclassical monocytes) and 11 DC subclusters (CD11b–CD11c+CD123dim conventional cDCs and CD11b–CD11c–CD123+ plasmacytoid pDCs). Cluster annotation numbers displayed in (A) correspond to the numbers shown in (B). (C) Boxplots showing the relative abundance (median and interquartile range) of distinct monocyte subclusters, analyzed at 2 or 3 consecutive time points as indicated on the x-axis, that are significantly more (top row) or less (middle row) prevalent in HSCT patients who developed aGVHD. DC subclusters most prevalent in therapy refractory aGVHD patients (nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy) are indicated in the bottom row. Healthy ctr, healthy control participants; HSCT ctr, patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD; Steroid-CR, patients who underwent HSCT and demonstrated aGVHD responsive to steroids; GVHD-CR, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy; GVHD-NR, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy. (D) Representative images of the abundant presence of CD163+ cells (stained in brown) in skin and colon biopsy samples from patients with aGVHD. Note the sporadic presence of CD163+ cells in colon and skin biopsy samples collected from patients suspected of skin or gut aGVHD after undergoing HSCT. These biopsy samples however displayed no convincing pathologic features of aGVHD. The biopsy sample obtained after MSC therapy initiation (right panel) is derived from one of the patients with refractory aGVHD who did not respond to steroids and MSC. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

CD163+cells are abundant in PBMC, skin, and GI tract samples of patients with acute GVHD. (A) Hierarchical stochastic neighbor embedding (HSNE)–guided dissection of blood-derived myeloid cells that belong either to the monocyte or DC lineage. (B) Heatmap showing 11 different monocyte subclusters (CD14+CD16– classical, CD14+CD16dim/intermediate, or CD14neg/dimCD16bright nonclassical monocytes) and 11 DC subclusters (CD11b–CD11c+CD123dim conventional cDCs and CD11b–CD11c–CD123+ plasmacytoid pDCs). Cluster annotation numbers displayed in (A) correspond to the numbers shown in (B). (C) Boxplots showing the relative abundance (median and interquartile range) of distinct monocyte subclusters, analyzed at 2 or 3 consecutive time points as indicated on the x-axis, that are significantly more (top row) or less (middle row) prevalent in HSCT patients who developed aGVHD. DC subclusters most prevalent in therapy refractory aGVHD patients (nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy) are indicated in the bottom row. Healthy ctr, healthy control participants; HSCT ctr, patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD; Steroid-CR, patients who underwent HSCT and demonstrated aGVHD responsive to steroids; GVHD-CR, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy; GVHD-NR, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy. (D) Representative images of the abundant presence of CD163+ cells (stained in brown) in skin and colon biopsy samples from patients with aGVHD. Note the sporadic presence of CD163+ cells in colon and skin biopsy samples collected from patients suspected of skin or gut aGVHD after undergoing HSCT. These biopsy samples however displayed no convincing pathologic features of aGVHD. The biopsy sample obtained after MSC therapy initiation (right panel) is derived from one of the patients with refractory aGVHD who did not respond to steroids and MSC. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Therapy-refractory aGVHD is associated with increased frequencies of DC subtypes and class-switched B cells

We further focused on specific non‒T-cell subclusters abundant in the HSCT group with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (supplemental Figure 6A). Although the overall DC lineage is proportionally decreased at t = 1 in all patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD, only patients not responding to MSC-based second-line therapy (supplemental Figure 3) showed marked frequencies of CD14+CD11bdimBDCA2−CD11c+ cDC (DC-6 and DC-7) (Figure 1C). Similar to subclusters Mo-8 and Mo-11 (Figure 1A-B), these cDC coexpressed CD163 and CD64, suggestive of a DC3-like phenotype.42 Subclusters DC-6 and DC-7 could be separated by CD13 expression. The frequencies of other cDC subclusters lacking CD163 (in particular DC-5) were markedly lower in steroid-refractory aGVHD patients who did not respond to MSC-based second-line therapy (supplemental Figure 6B). A third DC subcluster highly prevalent in aGVHD patients refractory to steroids and MSC-based second-line therapy was confined to the plasmacytoid DC (pDC) clusters (Figure 1B-C). This CD11c–CD123brightBDCA2+ subcluster (DC-9) also expressed CD56.

Various NK cell subclusters were also identified (supplemental Figure 6C). In line with earlier observations,43 CD56brightCD16– NK cells (NK-3) were highly prevalent in all patients undergoing HSCT (HSCT control group, HSCT with steroid-responsive aGVHD group, HSCT with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy group, and HSCT with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy group) who displayed incomplete recovery of CD4+ T cells (supplemental Figure 6D). In contrast, subcluster NK-1, expressing CD107a (a reported marker of functional activity44) and CD24, tended to be more prevalent in all steroid-refractory aGVHD patients regardless of their response to MSC-based second-line therapy.

Finally, we compared the prevalence of different HLA-DR+CD19+ B-cell subclusters among all study groups (Figure 2). Although B-cell frequencies (Figure 2C) and absolute counts (supplemental Figure 4) were considerably lower at t = 1 in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy group, these patients displayed a dominant population (median 40% of B cells) of CD27+CD38+CD24–IgD–IgM– B cells (B-1), which persisted over time. These cells likely represent class-switched plasmablasts.45 Transitional IgD+IgM+CD38+CD24+ B cells (B-5) were proportionally higher in HSCT control participants. Note that the latter patients were also exposed to prophylactic immune suppressive medication (Table 1). In contrast, several naïve B-cell subclusters were less prevalent in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (supplemental Figure 6E). Altogether, the CyTOF dataset shows that class-switched plasmablasts (B-1), CD163+cDCs (DC-6 and DC-7), and CD56+ pDC (DC-9) are non‒T-cell populations found predominantly in HSCT patients with progressive aGVHD nonresponsive to either steroids or MSC-based second-line therapy.

Patients with steroid-resistant GVHD display a selective and persistent increase of circulating plasmablasts. (A) Heatmap of B-cell subclusters with annotation numbers corresponding to data shown in (B-C). (B) Hierarchical stochastic neighbor embedding (HSNE) map of B-cell subclusters (left). Right panel shows the same HSNE map as depicted on the left, but subclusters are color annotated according to the patient group in which they are most prevalent. (C) Boxplots (median and interquartile range) showing frequencies of B-cell subclusters that are increased significantly or decreased in refractory patients with aGVHD (HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-NR]). GVHD-CR, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy; Healthy ctr, healthy control participants; HSCT ctr, patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD; Steroid-CR, HSCT patients with steroid-responsive aGVHD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Patients with steroid-resistant GVHD display a selective and persistent increase of circulating plasmablasts. (A) Heatmap of B-cell subclusters with annotation numbers corresponding to data shown in (B-C). (B) Hierarchical stochastic neighbor embedding (HSNE) map of B-cell subclusters (left). Right panel shows the same HSNE map as depicted on the left, but subclusters are color annotated according to the patient group in which they are most prevalent. (C) Boxplots (median and interquartile range) showing frequencies of B-cell subclusters that are increased significantly or decreased in refractory patients with aGVHD (HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-NR]). GVHD-CR, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy; Healthy ctr, healthy control participants; HSCT ctr, patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD; Steroid-CR, HSCT patients with steroid-responsive aGVHD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Persistent inflammation correlates with increased frequencies of effector and regulatory T cells expressing skin- or gut-homing receptors

Pronounced differences were found in the T-cell compartment of HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD either responsive or nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (Figure 3; supplemental Figures 5A, 7, and 8). Within the major CD4+ and CD8+ TCRαβ+ T-cell populations, antigen-naïve (CD45RA+CCR7+CD56‒) vs antigen-experienced effector (CD45RA+/−CCR7–CD56+) as well as CD4+CD25highCD127dim/– regulatory T-cell (Treg) populations were identified (Figure 3A). Both effector and Treg subclusters were separated further by the presence of chemokine receptors (chemokineRs) that facilitate migration to both the skin and GI tract.17,18 T cells, including TCRγδ+ T cells, expressing CXCR3, CCR9, and CCR10 further are referred to as chemokineRhigh T cells (Figure 3A; supplemental Figures 7B and 10). CXCR3dim/–CCR9–CCR10– effector T cells were designated as chemokineRlow subclusters. Of note, nearly all CD4+ effector T cells and Tregs expressed CCR4. Assessing the dynamics of the main CD4+ and CD8+ effector T-cell populations in patients who responded to either steroids (HSCT with steroid-responsive aGVHD group) or to steroids plus MSC (HSCT with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy group) revealed a significant decrease in chemokineRhigh populations between t = 1 and t = 3 (P < .05) (Figure 3B), whereas chemokineRlow T cells were increasing significantly (P < .05). HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy demonstrated a trend in the opposite direction. In each of the 3 aGVHD patient subgroups, chemokineRhigh CD4+ Tregs displayed similar kinetics as CD4+ effector T cells. Comprehensive analysis of T-cell subclusters furthermore revealed significant differences in subcluster frequencies before and after MSC therapy in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD either responsive or nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (Figure 3C; supplemental Figures 7A and 8). The t = 1 samples obtained before the first MSC infusion from HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy showed significantly higher frequencies of the CLA+ subcluster CD4-4 and the PD1+ subclusters CD4-11 and CD4-13 (all P < .05) than HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (Figure 3C). On the contrary, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy displayed higher frequencies of naïve CD4+ T-cell subclusters CD4-16.2 and CD4-17 and effector T-cell subclusters CD4-18 and CD4-27. Four weeks after initiation of MSC therapy (t = 3), chemokineRlow subclusters CD8-19 and CD8-23 were found predominantly in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy. In contrast, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy displayed a clear increase in 5 different chemokineRhigh CD8 subclusters CD8-4 to CD8-8, CD4-27, and CD4+ Treg subclusters CD4-6, CD4-16.1, and CD4-21. These findings point out that clinical improvement of aGVHD over time is associated with a marked decrease in circulating effector T cells with gut- and skin-homing capacities. In contrast, chemokineRhigh effector T cells and Tregs remain present at high frequencies in the blood of patients with persistent grade III-IV aGVHD.

Opposite kinetics of TCRαβ+ effector and regulatory T-cell frequencies separate patients with therapy-refractory aGVHD from those with therapy-responsive aGVHD. (A) Heatmap displaying phenotypically different CD4- or CD8-expressing T-cell subclusters, including CD4+ Tregs. Effector T-cell subclusters were separated on the combined presence (chemokineRhigh) or absence (chemokineRlow) of CXCR3, CCR9, and CCR10. Matching color codes on the y-axis identify the markers used for subcluster annotation. (B) Frequency of effector T-cell and Treg populations with differential expression of chemokine receptors (as defined in [A]) in 3 different patient groups over time (purple indicates HSCT patients with steroid-responsive aGVHD [Steroid-CR]; green indicates HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-CR]; red indicates HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-NR]). Differences in cluster frequencies before (t = 1) and after initiation of immune suppressive therapy (steroids only or steroids plus MSC) were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (C) Radial plots showing differences in individual T-cell subclusters found in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-CR in green) and HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-NR in red) before (left) and 1 week (center) or 4 weeks (right) after initiation of MSC treatment. Cluster numbers correspond to heatmap annotation in (A). Significantly more prevalent T-cell subclusters are shown in bold. Scale of radial plots represent cell frequency (×102) as percentage of the major CD4 or CD8 lineage. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01.

Opposite kinetics of TCRαβ+ effector and regulatory T-cell frequencies separate patients with therapy-refractory aGVHD from those with therapy-responsive aGVHD. (A) Heatmap displaying phenotypically different CD4- or CD8-expressing T-cell subclusters, including CD4+ Tregs. Effector T-cell subclusters were separated on the combined presence (chemokineRhigh) or absence (chemokineRlow) of CXCR3, CCR9, and CCR10. Matching color codes on the y-axis identify the markers used for subcluster annotation. (B) Frequency of effector T-cell and Treg populations with differential expression of chemokine receptors (as defined in [A]) in 3 different patient groups over time (purple indicates HSCT patients with steroid-responsive aGVHD [Steroid-CR]; green indicates HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-CR]; red indicates HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-NR]). Differences in cluster frequencies before (t = 1) and after initiation of immune suppressive therapy (steroids only or steroids plus MSC) were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (C) Radial plots showing differences in individual T-cell subclusters found in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-CR in green) and HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-NR in red) before (left) and 1 week (center) or 4 weeks (right) after initiation of MSC treatment. Cluster numbers correspond to heatmap annotation in (A). Significantly more prevalent T-cell subclusters are shown in bold. Scale of radial plots represent cell frequency (×102) as percentage of the major CD4 or CD8 lineage. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01.

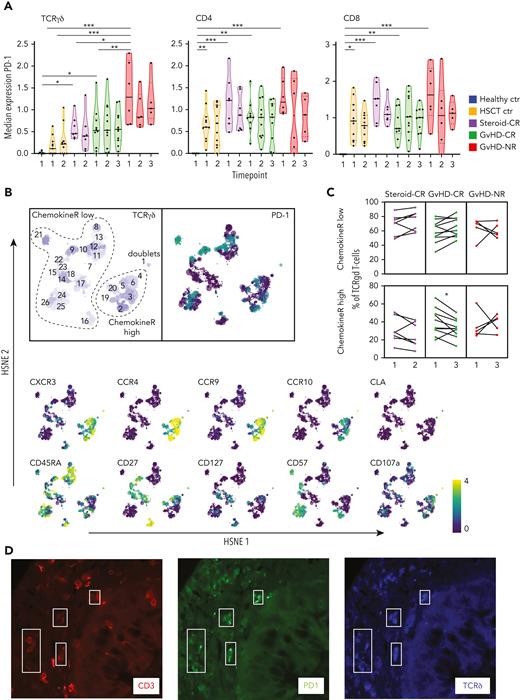

In all patients who underwent HSCT, the activation marker programmed death-1 (PD-1)-regulating T-cell activation and proliferation46 was expressed by several T-cell subclusters including TCRγδ+ cells (Figure 4). The highest median PD-1 expression was displayed by TCRγδ+ T cells derived from HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (Figure 4A). Similar to distinct CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets, we identified subpopulations within the TCRγδ+ T cells with high expression of CXCR3, CCR3, CCR9, and CCR10 and variable PD-1 expression (chemokineRhigh) (Figure 4B). Interestingly, chemokineRhigh TCRγδ+ T cells also showed a decrease over time in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy similar to chemokineRhigh TCRαβ+ T cells addressed in the previous section (P < .05) (Figure 4C). We also detected PD-1+ TCRγδ+ cells in GI-tract biopsy samples obtained from patients with severe visceral GVHD (Figure 4D).

Antigen-exposed TCRγδ+ T cells are present in the blood and GI tract of patients with severe intestinal GVHD. (A) Violin plots depicting median PD-1 expression levels on TCRγδ+ cells and TCRαβ+ CD4 or CD8 expressing T cells at the indicated time points in the different patient groups. (B) Hierarchical stochastic neighbor embedding (HSNE) map showing distinct subclusters of TCRγδ+ T cells found at all time points in all patients. Note the overlap among CXCR3, CCR4, CCR9, and CCR10 expression in TCRγδ+ cells (chemokineRhigh). (C) Frequency of chemokineRhigh TCRγδ+ T cells at time points 1 and 3 in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-CR) and HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-NR) (before and after MSC infusion) and at time points 1 and 2 in HSCT patients with aGVHD responsive to steroids (Steroid-CR). (D) Detection of TCRγδ+ T cells in a GI tract biopsy sample obtained from a patient with ongoing aGVHD. A combination of antibodies staining PD-1 (green), TCRδ (blue), and CD3 (red) was used to visualize PD-1-expressing TCRγδ+ T cells (marked by white quadrants; original magnification, ×400). Healthy ctr, healthy control participants; HSCT ctr, patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

Antigen-exposed TCRγδ+ T cells are present in the blood and GI tract of patients with severe intestinal GVHD. (A) Violin plots depicting median PD-1 expression levels on TCRγδ+ cells and TCRαβ+ CD4 or CD8 expressing T cells at the indicated time points in the different patient groups. (B) Hierarchical stochastic neighbor embedding (HSNE) map showing distinct subclusters of TCRγδ+ T cells found at all time points in all patients. Note the overlap among CXCR3, CCR4, CCR9, and CCR10 expression in TCRγδ+ cells (chemokineRhigh). (C) Frequency of chemokineRhigh TCRγδ+ T cells at time points 1 and 3 in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-CR) and HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-NR) (before and after MSC infusion) and at time points 1 and 2 in HSCT patients with aGVHD responsive to steroids (Steroid-CR). (D) Detection of TCRγδ+ T cells in a GI tract biopsy sample obtained from a patient with ongoing aGVHD. A combination of antibodies staining PD-1 (green), TCRδ (blue), and CD3 (red) was used to visualize PD-1-expressing TCRγδ+ T cells (marked by white quadrants; original magnification, ×400). Healthy ctr, healthy control participants; HSCT ctr, patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.

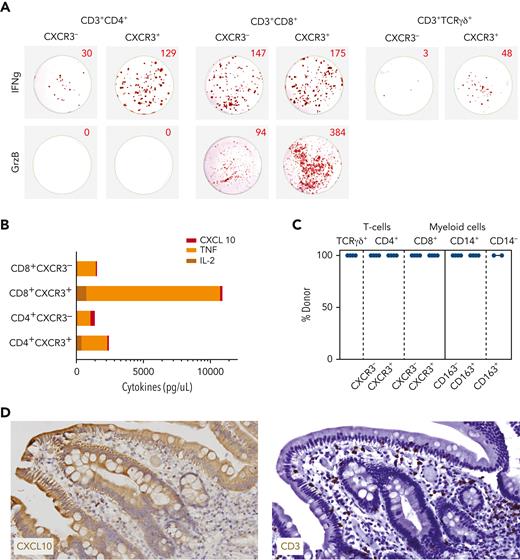

CXCR3-expressing T cells produce inflammation-promoting and tissue-destructive compounds

To address the functional properties of T cells that emerge around aGVHD onset, different T-cell subsets were isolated from 2 HSCT patients with steroid-responsive aGVHD, 1 HSCT patient with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy, and 1 HSCT patient with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy. Using the gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 9, we separated TCRαβ+ and TCRγδ+ T cells based on differential expression of CXCR3 and compared their potential to release granzyme B and IFN-γ (Figure 5A) as well as other cytokines (Figure 5B) after overnight stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin. CXCR3+ T cells expressing either TCRαβ+ or TCRγδ+ displayed higher production of IFN-γ as compared with their CXCR3– counterparts. Within the TCRαβ+ population, release of the cytolytic enzyme granzyme B was restricted to CD8+ T cells, with CXCR3+ cells containing the highest frequency of granzyme B-producing cells. CXCR3+CD8+ T cells also produced a substantial amount of tumor necrosis factor α and, to some extent, also interleukin 2.

CXCR3+ T cells are of donor origin and release inflammation-promoting compounds on short-term activation. (A) ELISpot wells showing IFN-γ (top row) and granzyme B (GrzB; bottom row) production by flow-sorted CD4+TCRαβ+ (left; 1600 cells/well), CD8+TCRαβ+ (center; 1600 cells/well), and TCRγδ+ (410 cells/well for CXCR3+ and 79 cells/well for CXCR3–) T cells plated in ELISpot plates (U-CyTech Biosciences) and stimulated overnight by PMA and ionomycin. (B) Supernatants from ELISpot assays using 65 000 or 12 500 cells (CD4+CXCR3– subset only) were harvested before cell lysis for testing by Luminex. CXCL10 (ligand binding to CXCR3), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin 2 (IL-2) levels are shown. Note that cytokine values for CD4+CXCR3– subset are corrected based on 5-fold less T-cell yield after sorting. (C) Results of short tandem repeats (STR) analysis performed on 20 000 flow-sorted TCRγδ+ T cells, TCRαβ+ T-cell subclusters separated according to the level of CXCR3 expression (supplemental Figure 9), and CD14+ myeloid subclusters separated according to the level of CD163 expression and CD14– myeloid cells. Chimerism data are representative for the results obtained from 4 different patients with aGVHD. (D) Detection of CXCL10+ cells (left) and CD3+ T cells (right), both in brown, in a duodenum biopsy sample obtained from a patient with steroid-refractory aGVHD. Note that CXCL10 is expressed by epithelial cells lining the villi as well as small lymphocytic cells residing in the lamina propria of the villi in the same localization as CD3+ T cells stained in a serial section.

CXCR3+ T cells are of donor origin and release inflammation-promoting compounds on short-term activation. (A) ELISpot wells showing IFN-γ (top row) and granzyme B (GrzB; bottom row) production by flow-sorted CD4+TCRαβ+ (left; 1600 cells/well), CD8+TCRαβ+ (center; 1600 cells/well), and TCRγδ+ (410 cells/well for CXCR3+ and 79 cells/well for CXCR3–) T cells plated in ELISpot plates (U-CyTech Biosciences) and stimulated overnight by PMA and ionomycin. (B) Supernatants from ELISpot assays using 65 000 or 12 500 cells (CD4+CXCR3– subset only) were harvested before cell lysis for testing by Luminex. CXCL10 (ligand binding to CXCR3), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin 2 (IL-2) levels are shown. Note that cytokine values for CD4+CXCR3– subset are corrected based on 5-fold less T-cell yield after sorting. (C) Results of short tandem repeats (STR) analysis performed on 20 000 flow-sorted TCRγδ+ T cells, TCRαβ+ T-cell subclusters separated according to the level of CXCR3 expression (supplemental Figure 9), and CD14+ myeloid subclusters separated according to the level of CD163 expression and CD14– myeloid cells. Chimerism data are representative for the results obtained from 4 different patients with aGVHD. (D) Detection of CXCL10+ cells (left) and CD3+ T cells (right), both in brown, in a duodenum biopsy sample obtained from a patient with steroid-refractory aGVHD. Note that CXCL10 is expressed by epithelial cells lining the villi as well as small lymphocytic cells residing in the lamina propria of the villi in the same localization as CD3+ T cells stained in a serial section.

Furthermore, we performed chimerism analysis on CXCR3+ effector T cells and CD163+ myeloid cells. All flow-sorted populations displayed 100% donor chimerism (Figure 5C). Hence, CXCR3+ effector T cells, which remain highly prevalent in patients with therapy-refractory aGVHD, are of donor origin and contain so-called licensed-to-kill effector cells with inflammation-promoting properties. Importantly, we also could show that the CXCR3-binding ligand CXCL10 is expressed by epithelial cells lining the villi and by individual lymphocytes residing in the lamina propria (Figure 5D).

Discussion

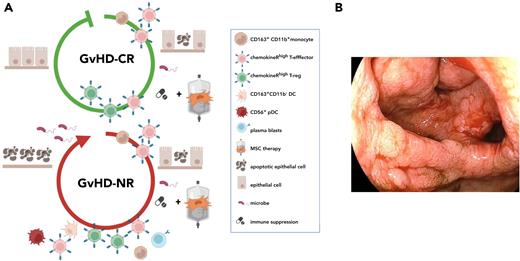

We report the results of the first CyTOF-based analysis of PBMCs derived from pediatric patients with aGVHD, who responded differently to either steroids alone or to steroids combined with MSC treatment.30,47 We found distinct immune populations in the blood early after aGVHD onset; several immune cell types seem to be associated uniquely with progressive, therapy-refractory aGVHD (steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy) (Figure 6). Unlike plasmablasts (data not shown), CD163+ myeloid cells and T cells resembling the chemokineRhigh T cells found after aGVHD onset could already be detected in PBMCs collected shortly before clinical manifestation of aGVHD, albeit in lower frequencies (supplemental Figure 10). Adhesion of leukocytes to endothelial cells lining blood vessels in the GI tract is a critical first step in the aGVHD pathologic process. These interactions involve, among others, the CXCR3-binding chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, which are highly expressed in the GI tract of mice after receiving an allogeneic bone marrow graft48 as well as in the GI tract of patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD (Figure 5D).49 Our study confirmed that aGVHD is associated with CXCR3+ T cells that coexpress CCR4, CCR9, CCR10, and occasionally CLA. These chemokineRhigh effector T cells remained proportionally high over time in patients with therapy-refractory aGVHD, but decreased in patients with treatment-responsive aGVHD. Along with classic TCRαβ+effector T cells, TCRγδ+ and CD4+ Tregs expressing the same set of chemokine receptors also are generated in patients with progressive aGVHD (Figures 3A-C and 4A). A recent study of PBMCs derived from adult patients who underwent HSCT also showed that Tregs express CCR4, CCR9, and CXCR3.50 Furthermore, tissue-specific Tregs appearing shortly after donor hematopoietic stem cell engraftment were shown to protect against skin and gut GVHD.51,52 Distinct shifts in proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory T-cell populations were also observed in a previous study on MSC-treated adult patients with aGVHD.53 Therefore, it seems likely that the marked increase of distinct chemokineRhigh Treg subclusters, as clearly observed in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy, acts as a compensatory mechanism counteracting on the various effector T-cell subpopulations that are activated over a prolonged period. ChemokineRhigh CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were most pronounced in patients with visceral aGVHD (supplemental Figure 11). Furthermore, T cells with skin-homing markers were not found solely in patients with skin inflammation; these patients also displayed CCR9+CXCR3+ T cells. Hence, homing-receptor expression does not seem to be related to specific organ involvement. We hypothesize that tissue accumulation of chemokineRhigh T cells seems primarily driven by ligand expression in aGVHD target organs (Figure 5D). Unbiased immune profiling also revealed the emergence of CD11b+CD163+ monocytes in all patients who demonstrate aGVHD. These cells were less frequent in patients undergoing HSCT without aGVHD and in healthy control participants respectively, confirming increased myeloid output in patients with aGVHD.54 Because CD163+ monocytes were already detectable before clinical manifestation of aGVHD (supplemental Figure 10), their presence seems driven by the degree of tissue inflammation and not by initiation of glucocorticoid treatment. CD163+ cDCs and CD56+ pDCs were other prominent and novel immune populations found early in the course of the disease in patients with progressive, therapy-refractory aGVHD. CD163 is a scavenger receptor that serves as an innate immune sensor.55 Single-cell protein and RNA analysis performed in other studies revealed that CD163+ cells in blood actually comprise 2 closely related inflammatory CD14+56 and conventional CD14– DC subtypes,57 previously defined as DC3.42,56,58 In patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, DC3 positively correlate with disease activity.56 CD163+ myeloid cells are specifically recruited to inflamed tissues, where they develop into tissue-resident inflammatory macrophage-like cells that upregulate messenger RNA coding for the production of cytolytic enzymes and factors like CXCL2, which attracts neutrophilic granulocytes.59 The degree of skin infiltration by CD163+ macrophages has been shown to correlate with aGVHD severity as well as with steroid-resistant aGVHD.60,61 Our study revealed that CD163+ myeloid cells also are abundant in GI tract biopsy samples collected from patients with visceral aGVHD. GI tract biopsy samples collected after MSC therapy from nonresponding patients also displayed high numbers of CD163+ cells (Figure 1D). HLA-DRdimCD14+CD163+ macrophage-like cells isolated from aGVHD-affected skin biopsy samples are capable of producing chemoattractant compounds like CCL5 and CXCL10 on lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation.7 Because these chemokines play an active role in the recruitment of DC, monocytes, effector T cells, and CD56+CD107a+ innate lymphoid cells, tissue-accumulating CD163+ cells should be seen as a second key aGVHD-promoting cell type. Our study also demonstrated the power of high-dimensional immune profiling with respect to the discovery of cells with unconventional marker expression. This is exemplified by the identification of a CD56+CD38+BDCA-2+CD11c– pDC subset (DC-9) in patients with refractory aGVHD. CD56 not only delineates 2 distinct populations of NK cells, but this marker is also expressed by monocytes, DCs, and activated T cells,62 as shown in supplemental Figure 5. While CD56+ monocytes are increased in other tissue-eroding pathologic conditions,63,64 preliminary evidence suggests that CD56+CD123+ DCs represent a unique DC subset with acquired cytolytic function that bears more resemblance to inflammatory DCs than to conventional pDCs.65-67 Whether the CD163+ or CD56+ DC subsets identified in this study contain cells expressing CXCR3 and CCR5, as earlier reported in the context of aGVHD,68 needs to be confirmed. Microbial triggering of toll-like receptors expressed by DCs and monocytes boosts the recruitment of additional innate and adaptive immune cells, including effector T cells and plasmablasts.69 Among CXCR3+ T cells, we also detected PD-1+ TCRγδ+ cells in blood (Figure 4A) and gut biopsy samples of patients with aGVHD (Figure 4D). Conflicting results on the role of TCRγδ+ T cells in aGVHD pathogenesis have been reported.70-72 Considering their tropism for epithelial tissues, where they contribute to immune surveillance against invading pathogens,73 we speculate that activation of TCRγδ+ donor T cells in patients with aGVHD is a secondary event, driven by the amount of microbes entering the body via damaged epithelial barriers. In line with this hypothesis, we also observed an increased frequency of IgM– class-switched plasmablasts exclusively among B cells present in patients with therapy-refractory aGVHD (Figure 2C). Because B-cell reconstitution generally is slow after myeloablative conditioning, information on the role of B cells and (allo)antibodies in aGVHD is limited. B cells likely contribute to alloimmune T-cell activation, because aGVHD can be treated successfully with B-cell‒depleting antibodies.74 This may explain the reported rise in B-cell‒activating factors in patients with aGVHD.74,75 In refractory aGVHD, B-cell activation and class-switching is more likely driven by the abundant presence of microbes in damaged tissues. We speculate that IgG antibodies produced by these plasmablasts facilitate opsonization and uptake of microbes by CD64+ phagocytes (Figure 1B) and CD16+ NK cells (supplemental Figure 5). IgA- or IgG-expressing B cells are increased in patients with mucosal infections,76 suggesting that these cells are crucial for maintaining immune homeostasis in mucosal tissues. Indeed, most circulating plasmablasts found in healthy donors express CCR10, CCR9, and integrin α4β7, facilitating their migration to both the skin and GI tract.77 Hence, timely control of translocating microbes and subsequent activation of additional immune cells beyond classic CD8+ effector T cells seems to be a critical factor determining aGVHD outcome.

Different patterns of immune cell activation and tissue destruction in patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responding differently to MSC therapy. (A) Graphical depiction of the appearance of characteristic immune populations and degree of epithelial cell damage in patients with aGVHD either responding (top) or refractory (bottom) to second-line immunosuppressive therapy. Both patient groups were treated consecutively with first-line immunosuppressive and second-line MSC therapy. HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD either responsive or nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy groups (GVHD-CR and GVHD-NR, respectively) initially showed high frequencies of circulating CD163+CD11b+ monocytes and CXCR3+CCR9+CCR10+ effector T cells shortly after introduction of immunosuppressive therapy. Patients nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy further showed increased frequencies of CD163+CD11b– DCs, CD56+ DCs, and plasmablasts, which persisted over time. In patients responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy, who showed complete resolution of all clinical aGVHD symptoms, CXCR3+CCR9+CCR10+ effector T cells, along with CXCR3+CCR9+CCR10+ Tregs, decreased over time. These populations remained high in the group of patients nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy, indicative of escalating immune reactivity leading to progressive tissue damage in aGVHD target organs, loss of epithelial barrier function, and concurrent infectious complications. (B) Endoscopy image showing the macroscopic appearance of the colon of one of the patients nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy. The biopsy was taken after MSC therapy was initiated.

Different patterns of immune cell activation and tissue destruction in patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responding differently to MSC therapy. (A) Graphical depiction of the appearance of characteristic immune populations and degree of epithelial cell damage in patients with aGVHD either responding (top) or refractory (bottom) to second-line immunosuppressive therapy. Both patient groups were treated consecutively with first-line immunosuppressive and second-line MSC therapy. HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD either responsive or nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy groups (GVHD-CR and GVHD-NR, respectively) initially showed high frequencies of circulating CD163+CD11b+ monocytes and CXCR3+CCR9+CCR10+ effector T cells shortly after introduction of immunosuppressive therapy. Patients nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy further showed increased frequencies of CD163+CD11b– DCs, CD56+ DCs, and plasmablasts, which persisted over time. In patients responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy, who showed complete resolution of all clinical aGVHD symptoms, CXCR3+CCR9+CCR10+ effector T cells, along with CXCR3+CCR9+CCR10+ Tregs, decreased over time. These populations remained high in the group of patients nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy, indicative of escalating immune reactivity leading to progressive tissue damage in aGVHD target organs, loss of epithelial barrier function, and concurrent infectious complications. (B) Endoscopy image showing the macroscopic appearance of the colon of one of the patients nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy. The biopsy was taken after MSC therapy was initiated.

Patients with aGVHD who become refractory to second-line immunosuppressive therapy are at high risk of transplantation-related mortality caused by disseminated infections, organ dysfunction, or early leukemia relapse.23,78 Indeed, 5 of 6 patients in the group of HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy were not alive at 1 year after graft infusion (Table 1). Intriguingly, the sole long-term survivor in this study group showed an effector T-cell signature more similar to signatures displayed by aGVHD patients in whom clinical symptoms ameliorated after combined steroid and MSC therapy (Figures 3B and 4C). As seen in most patients who undergo HSCT and are treated with high-dose immune suppressive drugs over a prolonged period, the patient’s aGVHD course was complicated by viral infection‒induced diarrhea. After viral infections were controlled and steroids had been tapered, the patient received a third MSC product, which was accompanied by a swift and complete disappearance of all GI-tract symptoms.

To conclude, even before initiation of MSC therapy, we found a unique immune signature in the blood that distinguishes patients with therapy-refractory aGVHD from those with therapy-responsive aGVHD. These discriminative immune populations displayed features indicative of escalating immune reactivity within the T-cell, B-cell, and myeloid compartment of patients with therapy-refractory aGVHD. Efforts to validate the new immune signature, as well as the tissue-homing potential and functional properties of newly identified DC and B-cell subpopulations, are currently being made in conjunction with a phase 3 clinical trial (EudraCT identifier, 2012-004915-30). Because the collection of tissue biopsy samples is an invasive procedure, monitoring of distinct immune populations in blood may help to evaluate clinical efficacy of first-line immune suppression and may facilitate decision-making to effect timely switching to alternative treatment options to prevent early transplantation-related mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Olga Karpus, Sanne Hendriks, Guillaume Beyrend, and Monique van Ostaijen-ten Dam for excellent support in antibody panel design, live barcoding, CyTOF data analysis, and data acquisition by spectral flow cytometry. The authors acknowledge the coordinators and operators of the Flow Cytometry Core Facility of the Leiden University Medical Center (https://www.lumc.nl/research/facilities/fcf), directed by F. J. T. Staal and J. J. M. van Dongen, for technical support and cell sorting assistance. The authors also acknowledge Yvonne Vaal and Els van Beelen for quantification of cytokine data, Inge Briaire-de Bruijn for advice on CXCL10 immunostaining, and Joachim Schweizer for providing the endoscopy image shown in Figure 6. The authors also thank Dietger Niederwieser and Janine Melsen for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under grant agreement number 643580.

Authorship

Contribution: A.G.S.v.H., J.S.S., M.J.D.v.T., and W.E.F. conceptualized the study; A.G.S.v.H., J.S.S., S.L., and A.-S.W. devised the methodology; J.S.S., A.G.S.v.H., J.B., S.L., S.T., A.S., and R.T. generated and analyzed the data; A.G.S.v.H. supervised the experiments; A.G.S.v.H. and J.S.S. wrote the original draft; and M.J.D.v.T., W.E.F., S.T., S.L., M.v.P., B.O.R., J.J.Z., A.C.L., and K.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: W.E.F. is chairman of an Independent Data Monitoring Committee for Glycostem Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for Astrid G. S. van Halteren is Department of Internal Medicine/Clinical Immunology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

The current affiliation for Anna-Sophia Wiekmeijer is ISA Pharmaceuticals BV, Oegstgeest, The Netherlands.

The current affiliation for Melissa van Pel is NecstGen, Leiden, The Netherlands.

The current affiliation for Koen Schepers is Department of Dermatology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Correspondence: Astrid G. S. van Halteren, Department of Internal Medicine/Clinical Immunology, Erasmus Medical Center, PO Box 2040, 3000 CA Rotterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: a.vanhalteren@erasmusmc.nl.

References

Author notes

∗A.G.S.v.H., J.S.S., M.J.D.v.T., and W.E.F. contributed equally to this study.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Astrid G. S. van Halteren, a.vanhalteren@erasmusmc.nl.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Patients with steroid-resistant GVHD display a selective and persistent increase of circulating plasmablasts. (A) Heatmap of B-cell subclusters with annotation numbers corresponding to data shown in (B-C). (B) Hierarchical stochastic neighbor embedding (HSNE) map of B-cell subclusters (left). Right panel shows the same HSNE map as depicted on the left, but subclusters are color annotated according to the patient group in which they are most prevalent. (C) Boxplots (median and interquartile range) showing frequencies of B-cell subclusters that are increased significantly or decreased in refractory patients with aGVHD (HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-NR]). GVHD-CR, HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy; Healthy ctr, healthy control participants; HSCT ctr, patients who underwent HSCT without aGVHD; Steroid-CR, HSCT patients with steroid-responsive aGVHD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/141/11/10.1182_blood.2022015734/4/m_blood_bld-2022-015734-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1762589328&Signature=GhDpm7klsFX0QDAqSkX6FV-ijK-4gC42tEMVrBFXNCGeFsKKU8ukhJsa35puebkjdaiKloKI9xt~ux3PjvvimFXNk7rhrkJQVTH2axUwNYDZB-yRgxo8ZscHaLyYfiBA0FSxAAgOIr7SSYz1h91ktybSNHKdLCVZWGCqCNAhrnc4TLQhRo9zDn6DbFwvWR9Jo733EMTjHadFD0vdts9~x76HZi2wtlSN~O05Cv4~X6qnhxJLHCOkevy0CCTDurVVNdLAmW8yqfi66b9KxEd0S~q0IJYfog6mzMHp4uGqWwoEku-4Cu6JYc8gkrAqUXL3oIPmFEgcKwgJQcEyWoH4ag__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Opposite kinetics of TCRαβ+ effector and regulatory T-cell frequencies separate patients with therapy-refractory aGVHD from those with therapy-responsive aGVHD. (A) Heatmap displaying phenotypically different CD4- or CD8-expressing T-cell subclusters, including CD4+ Tregs. Effector T-cell subclusters were separated on the combined presence (chemokineRhigh) or absence (chemokineRlow) of CXCR3, CCR9, and CCR10. Matching color codes on the y-axis identify the markers used for subcluster annotation. (B) Frequency of effector T-cell and Treg populations with differential expression of chemokine receptors (as defined in [A]) in 3 different patient groups over time (purple indicates HSCT patients with steroid-responsive aGVHD [Steroid-CR]; green indicates HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-CR]; red indicates HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy [GVHD-NR]). Differences in cluster frequencies before (t = 1) and after initiation of immune suppressive therapy (steroids only or steroids plus MSC) were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. (C) Radial plots showing differences in individual T-cell subclusters found in HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD responsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-CR in green) and HSCT patients with steroid-refractory aGVHD nonresponsive to MSC-based second-line therapy (GVHD-NR in red) before (left) and 1 week (center) or 4 weeks (right) after initiation of MSC treatment. Cluster numbers correspond to heatmap annotation in (A). Significantly more prevalent T-cell subclusters are shown in bold. Scale of radial plots represent cell frequency (×102) as percentage of the major CD4 or CD8 lineage. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/141/11/10.1182_blood.2022015734/4/m_blood_bld-2022-015734-gr3.jpeg?Expires=1762589328&Signature=LlDM1-4051jQzu4mTbWWtRrQBAz4ajSW5XmAEkDSXnBcLHxzy~vNEB~y12sgAEIVy0yZ40-a7Srw9cjLNDQ4ry5qODFRKJ~Grpbe8x4Oweg37Z~lkJKf86QtnCdddprXzLtlWVVB98gW0ULBwfQIVZSHdqPaIGhgmyUTNM8YRLw1684OtarpKPjTV6dMTLvtBJ5lbX~brNv7heTTMvmrJs5LNO8yfm4jg-iWj8qNNAq3g95KzOY2zuhDSmstiWWkz7xg6QzpXmbdtb3wRlICSZDI2Q-CfPzWqn-cYXphEub2jrAJEOmP0pgaWQrwkc-pObex-MCmx4HS-FkTKPWYeA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal