In this issue of Blood, Schavgoulidze et al validate the importance of the cytogenetic abnormality del(1p32) in risk stratification by analyzing a large cohort of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM). Importantly, the study also identifies an ultra high-risk group (UHR) with biallelic deletion, which demonstrates significantly adverse outcomes following current standard frontline treatment.1

The addition of cytogenetic criteria (del(17p) and/or t(4;14) and/or t(14;16)) as part of the revised International Staging System (R-ISS) represented a major advance towards improving risk stratification in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.2 Subsequently, the importance of additional cytogenetic and genomic abnormalities such as 1q gain/amplification and TP53 mutation status has been highlighted in defining cohorts of patients with particularly poor outcomes following non–risk-adapted therapeutic strategies. A UHR population of double-hit patients was identified in a report from the Myeloma Genome Project, based on biallelic inactivation of TP53 and amplification of CKS1B (1q21), which was associated with a median overall survival (OS) of only 21 months.3

Also, the deleterious impact of certain criteria in the R-ISS such as t(4;14) and/or t(14;16) appear to be abrogated by current standard-of-care triplet treatment regimens, which combine immunomodulatory drugs, proteasome inhibitors, and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), in eligible patients and maintenance strategies. Therefore, the criteria for risk stratification need ongoing reevaluation in light of new data pertaining to disease biology and treatment outcomes.

Significant progress in the availability of new therapeutic options over the past 2 decades has been associated with a marked improvement in progression-free survival and OS for the majority of patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.4 Unfortunately, these non–risk-adapted empiric strategies have not been successful in a subgroup of patients, who continue to have an OS <5 years.

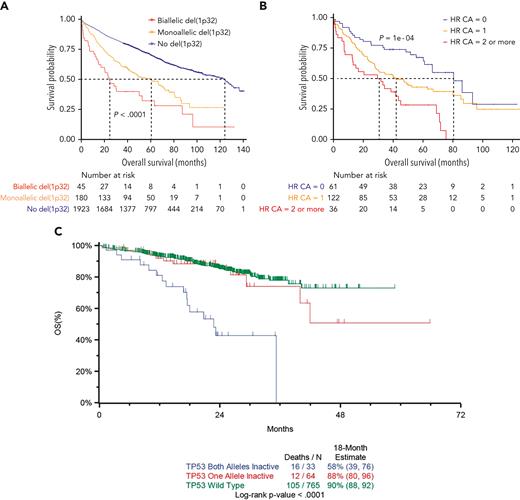

A consensus clinical definition for these high-risk (HR) groups is a median OS <5 years and <3 years for UHR patients.5 The median OS of 25 months for patients with biallelic 1p32 deletion in the current study satisfies the criterion for inclusion in the UHR category (see figure panel A). It also highlights the importance of monoallelic deletion (median OS, 60 months) and the cytogenetic abnormality of del(1p32) (median OS, 49 months) in identifying HR NDMM patients. Notably, this finding is observed in a substantial proportion, 11%, of patients at diagnosis. These findings need to be considered in updated risk-stratification criteria, around which prospective risk-adapted clinical trials can be designed. The phase 2 Optimum/Muknine trial for UHR patients included del(1p) in the criteria for eligibility and showed a benefit for an intensified treatment approach using a quintuplet induction (daratumumab, bortezomib, lenalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone), augmented ASCT, and quadruplet (daratumumab, bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone) consolidation strategy.6

(A) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients according to del(1p32) status. See Figure 2A in the article by Schavgoulidze et al that begins on page 1308. (B) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients with del(1p32) according to the association with other high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, defined by the presence of del(17p), t(4;14), and/or gain(1q). See Figure 4 in the article by Schavgoulidze et al that begins on page 1308. (C) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve by TP53 biallelic, monoallelic, or wild-type status. Reproduced from Walker et al,3 published under a CC BY 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

(A) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients according to del(1p32) status. See Figure 2A in the article by Schavgoulidze et al that begins on page 1308. (B) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients with del(1p32) according to the association with other high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, defined by the presence of del(17p), t(4;14), and/or gain(1q). See Figure 4 in the article by Schavgoulidze et al that begins on page 1308. (C) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve by TP53 biallelic, monoallelic, or wild-type status. Reproduced from Walker et al,3 published under a CC BY 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

This study also corroborates the negative prognostic impact of multiple HR cytogenetic abnormalities (see figure panel B), adding to the authors’ previous work in this area,7 and suggests that the biallelic deletion of 1p32 may have a similar prognostic impact to biallelic TP53 mutations, a well-recognized marker of UHR myeloma, in which the median OS is 24 months (see figure panel C).3 Another key message is the specification of the importance of the locus of del(1p), with only del(1p32) appearing to be useful in prognostication.

An additional important finding from the current analysis includes the equivalence of the different platforms (FISH/SNP arrays/NGS) used, which will help in discussions regarding standardization of methodology and cutoffs; this is essential if cytogenetic and genomic criteria are to be incorporated into risk-adapted treatment strategies outside of clinical trials.

However, it must be noted that this is a retrospective analysis of a large intergroup cohort of patients, with its attendant caveats, including missing data, and, therefore, corroboration of the impact of del(1p32) on outcomes from prospective clinical trial data sets is required, along with analysis of its impact on other known genomic negative prognostic markers, mainly TP53 mutations and 1q amplification.

It is anticipated that the results of this study will be pivotal in the effort to accurately define HR and UHR myeloma patients at diagnosis and disease progression, adding to data provided by the mSMART, EMC92/SKY92, UAMS GEP70, and CoMMpass criteria.8 This information will aid the design of prospective risk-adapted clinical trials to eventually improve outcomes for patients in this area of high unmet need.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.K. is a member of the advisory boards of Janssen, Celgene, Amgen, and Kyowa-Kirin, Mundipharma.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal