Abstract

Metabolic rewiring and cellular reprogramming are trademarks of neoplastic initiation and progression in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Metabolic alteration in leukemic cells is often genotype specific, with associated changes in epigenetic and functional factors resulting in the downstream upregulation or facilitation of oncogenic pathways. Targeting abnormal or disease-sustaining metabolic activities in AML provides a wide range of therapeutic opportunities, ideally with enhanced therapeutic windows and robust clinical efficacy. This review highlights the dysregulation of amino acid, nucleotide, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism in AML; explores the role of key vitamins and enzymes that regulate these processes; and provides an overview of metabolism-directed therapies currently in use or development.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clonal disorder of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) characterized by abnormal growth, differentiation blockade, and accumulation of immature myeloblasts.1 Clinical manifestations include various types of pancytopenia (and the complications thereof), as well as constitutional symptoms. Epidemiologically, AML is the most common form of acute leukemia in adults, and although it occurs across a spectrum of age groups, it is seen predominantly in older individuals.2 Induction chemotherapy, followed by a consolidation phase of additional chemotherapy and/or an allogeneic stem cell transplant, has remained the mainstay of initial AML treatment, but many patients fail to achieve remission or experience a relapse of the disease.3-5 Advances, including the successes of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) inhibitors,6,7 FLT3 inhibitors,8 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitors combined with hypomethylating agents (HMAs)9-11 have been directed toward patients with relapsed/refractory disease or elderly patients. Still, outcomes achieved with current therapies remain suboptimal, arguing for the development of novel therapeutic approaches.

Emerging literature has shown that metabolic perturbations, centered on specific metabolites and their related pathways, play pivotal roles in leukemogenesis and disease progression. These alterations, which are often entangled with underlying genetic, epigenetic, and functional factors facilitate proleukemic processes ranging from cellular transformation to chemotherapy resistance. Therefore, one avenue toward the development of novel therapies focuses on identifying and manipulating leukemia-specific metabolic vulnerabilities.12 Herein, we review recent advances in the characterization of metabolic pathways in AML, with a focus on potential therapeutic targets.

Amino acid metabolism and AML

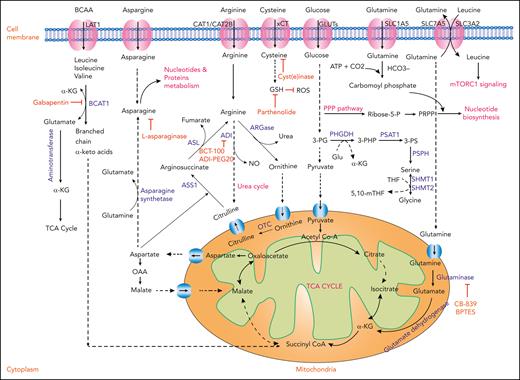

Amino acids play a critical role in protein synthesis. Their derivatives serve as energy and nucleotide sources; maintain reduction-oxidation balance; and contribute to homeostatic, epigenetic, and protein regulation. Cancer cells and healthy cells diverge in their relative production, uptake, and downstream utilization of amino acids. It is clear from the interrogation of the AML stem cell metabolome that amino acid metabolism represents a point for therapeutic intervention (Figure 1).13

Amino acid metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. Schematic representation showing the cellular uptake and utilization of select amino acids and their downstream intermediates. Enzymes with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue. Inhibitory compounds or proteins are highlighted in red. Biological outputs and metabolic pathways are highlighted in pink. ADI, arginine deaminase; ASL, arginosuccinate lyase; ASN, asparagine; ASS1, arginosuccinate synthetase 1; NO, nitric oxide; OAA, oxaloacetic acid; OTC, ornithine transcarbamylase; PSAT1, phosphoserine aminotransferase 1; PSPH, phosphoserine phosphatase; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; 3-PHP, 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate; 3-PS, 3-phosphoserine; THF, tetrahydrofolate; 5,10-mTHF, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate.

Amino acid metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. Schematic representation showing the cellular uptake and utilization of select amino acids and their downstream intermediates. Enzymes with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue. Inhibitory compounds or proteins are highlighted in red. Biological outputs and metabolic pathways are highlighted in pink. ADI, arginine deaminase; ASL, arginosuccinate lyase; ASN, asparagine; ASS1, arginosuccinate synthetase 1; NO, nitric oxide; OAA, oxaloacetic acid; OTC, ornithine transcarbamylase; PSAT1, phosphoserine aminotransferase 1; PSPH, phosphoserine phosphatase; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; 3-PHP, 3-phosphohydroxypyruvate; 3-PS, 3-phosphoserine; THF, tetrahydrofolate; 5,10-mTHF, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate.

Essential amino acids

Essential amino acids cannot be synthesized de novo or are inadequately synthesized relative to metabolic requirements.14 Of 20 proteinogenic amino acids, 9 are considered essential for normal cellular function. Among these, branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) (Figure 1), methionine, and tryptophan have been studied in AML. Related targets and mechanisms of action are summarized herein and in Table 1.

Compounds FDA approved or under preclinical and clinical development that target AML metabolism

| Serial number . | Drugs/compounds . | Enzymes/metabolic pathways affected and its mechanism . | In vitro/preclinical/clinical trials . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid metabolism and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 1 | Gabapentin | BCAT1 inhibitor/BCAA depletion; accumulation of αKG and impaired leukemogenesis. | In vitro | 15 |

| 2 | SETD2-IN-1 TFA | SETD2 inhibitor; preventing the transfer of methyl groups from SAM to H3K36 by SETD2. | Preclinical | 16 |

| 3 | SAHH inhibitor | SAHH inhibitor; preventing the conversion of SAH to homocysteine, thereby altering the SAM:SAH ratio and disrupting the SAM cycle. | Preclinical | 16 |

| 4 | Indoximod (1MT), epacadostat (INCB024360), and linrodostat (BMS986205) | IDO inhibitors; activating immune system (T cells and natural killer cells). | Preclinical/phase 1 | 17, 18 |

| 5 | CB-839, BPTES | GLS inhibitor/glutamine depletion; decreased OXPHOS, reduced GSH, and increased ROS. | Preclinical | 19 |

| 6 | ASNase + Ara-C | Depletion of circulating asparagine. | Phase 1/2 | 20 |

| 7 | BCT-100, ADI-PEG20 | Depletion of extracellular and intracellular arginine concentrations. | Preclinical | 21, 22 |

| 8 | Cyst(e)inase | Depletion of cysteine; reduced extracellular L-cysteine, depleted intracellular GSH, enhanced intracellular ROS, induced cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis. | Preclinical | 23 |

| 9 | Parthenolide | Depletion of GSH in cysteine metabolism; depleted GSH and inhibited GSH metabolic enzymes (eg, GCLC and GPX1), and induced oxidative stress. | In vitro | 24 |

| 10 | WQ-2101 + Ara-C | Inhibition of PHGDH. | Preclinical | 25 |

| 11 | RZ-2994, SHIN-2 | Inhibition of SHMT1 and SHMT2. | Preclinical | 26, 27 |

| FA metabolism and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 12 | Dehydrocurvularin | ATP citrate lyase inhibition. | Preclinical | 28 |

| 13 | Bezafibrate + medroxyprogesteron acetate | Prostaglandin inhibition. | In vitro | 29, 30 |

| 14 | Statin-dipyridamole | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor/MVA biosynthesis inhibition. | Preclinical | 31 |

| 15 | Statin + (venetoclax or navitoclax) | MVA biosynthesis inhibition, BCL-2 and BCL-XL inhibitor, and upregulation of the p53 protein. | In vitro | 32 |

| 16 | Statin | MVA biosynthesis inhibition; upregulation of the p53 protein and isoprenylation of the Rho and Ras GTPases. | Phase 2 | 33 |

| 17 | LCL204 | Ceramide inhibition. | Preclinical | 34 |

| Nucleotide metabolism and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 18 | 6-thioguanine | PRPP amidotransferase inhibitor. | Clinical trials | 35 |

| 19 | FF-10501 | IMPDH inhibitor/inhibit purine metabolism. | Phase 1 (#NCT02193958) | 36, 37 |

| 20 | Ara-C, gemcitabine | Pyrimidine analog/inhibit nucleotide biosynthesis. | FDA approved | 38 |

| 21 | BAY-2402234 ASLAN003 PTC299 | Dihydrofolate dehydrogenase inhibition. | Phase 1 (#NCT03404726) Phase 2 (#NCT03451084) Phase 3 (#NCT03761069) | 39, 40, 41 |

| 22 | 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-O-monophosphate[10] | Thymidylate synthetase (TS) inhibitor/reduce thymidine nucleotide. | Preclinical | 42 |

| Glycolytic and mitochondrial OXPHOS and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 23 | 2,5-anhydro-D-mannitol + Ara-C | Fructose analog/inhibit GLUT5. | Preclinical | 43 |

| 24 | 2-DG | HK/glycolytic pathway; compete with glucose and phosphorylated into 2-DG-6-P. | Preclinical | 44, 45, 46 |

| 25 | 3-PO | PFKFB3 inhibitor/glycolytic pathway; suppressed glucose uptake and decreased intracellular lactate levels. | Preclinical | 47 |

| 26 | TT-232 | PKM2 inhibitor/glycolytic pathway; induced apoptosis and promoted autophagy. | Preclinical | 48 |

| 27 | CPI-613 (devimistat) | PDH and αKG-dehydrogenase complexes inhibition/TCA cycle. | Phase 3 (#NCT03504410) | 49 |

| 28 | 2,2-dichloroacetophenone | Inhibits PDK1, increased the activation of proapoptotic protein (PARP and caspase 3), decreased the expression of antiapoptotic protein (BCL-XL, BCL-2). | Preclinical | 50 |

| 29 | Ivosidenib (AG-120) Enasidenib (AG221) | IDH1 inhibitor; reduce 2-HG IDH2 inhibitor and 2-HG synthesis. | FDA approved | 6, 7, 51 |

| 30 | ABT-737, ABT-264 | OXPHOS inhibition. | In vitro | 52 |

| 31 | Venetoclax + azacitidine | TCA cycle and OXPHOS inhibition. | FDA approved | 11, 53 |

| 32 | 2′3′-dideoxycytidine | mtDNA polymerase γ inhibition, inhibition of mtDNA replication and OXPHOS. | Preclinical | 54, 55 |

| 33 | 2-C-methyladenosine | Inhibition of OXPHOS and termination of mitochondrial transcription. | Preclinical | 56 |

| Vitamins and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 34 | Vitamin C | Cofactor of Fe2+ and αKG-dependent dioxygenases, promotes TET2 activity to limit HSPC self-renewal and leukemogenesis. | Clinical trials (#NCT03526666 and #NCT02877277) | 57, 58, 59 |

| 35 | Isoniazid, 4′-O-methoxypyridoxine | Inhibition of PLP/pyridoxal kinase activity. | Preclinical | 60 |

| 36 | ATRA + arsenic trioxide | Overcome the differentiation arrest through transcriptional de-repression and degradation of PML-RARA. | Phase 3 (#NCT00482833) | 61 |

| Resistance mechanisms to the current treatment | ||||

| 37 | Venetoclax + azacitidine + tedizolid | Inhibition of mitochondrial translation. | Preclinical | 62 |

| 38 | Venetoclax + ibrutinib Venetoclax + cobimtinib | OXPHOS and Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibition. OXPHOS and MEK inhibition. | Preclinical | 63, 64 |

| Serial number . | Drugs/compounds . | Enzymes/metabolic pathways affected and its mechanism . | In vitro/preclinical/clinical trials . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid metabolism and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 1 | Gabapentin | BCAT1 inhibitor/BCAA depletion; accumulation of αKG and impaired leukemogenesis. | In vitro | 15 |

| 2 | SETD2-IN-1 TFA | SETD2 inhibitor; preventing the transfer of methyl groups from SAM to H3K36 by SETD2. | Preclinical | 16 |

| 3 | SAHH inhibitor | SAHH inhibitor; preventing the conversion of SAH to homocysteine, thereby altering the SAM:SAH ratio and disrupting the SAM cycle. | Preclinical | 16 |

| 4 | Indoximod (1MT), epacadostat (INCB024360), and linrodostat (BMS986205) | IDO inhibitors; activating immune system (T cells and natural killer cells). | Preclinical/phase 1 | 17, 18 |

| 5 | CB-839, BPTES | GLS inhibitor/glutamine depletion; decreased OXPHOS, reduced GSH, and increased ROS. | Preclinical | 19 |

| 6 | ASNase + Ara-C | Depletion of circulating asparagine. | Phase 1/2 | 20 |

| 7 | BCT-100, ADI-PEG20 | Depletion of extracellular and intracellular arginine concentrations. | Preclinical | 21, 22 |

| 8 | Cyst(e)inase | Depletion of cysteine; reduced extracellular L-cysteine, depleted intracellular GSH, enhanced intracellular ROS, induced cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis. | Preclinical | 23 |

| 9 | Parthenolide | Depletion of GSH in cysteine metabolism; depleted GSH and inhibited GSH metabolic enzymes (eg, GCLC and GPX1), and induced oxidative stress. | In vitro | 24 |

| 10 | WQ-2101 + Ara-C | Inhibition of PHGDH. | Preclinical | 25 |

| 11 | RZ-2994, SHIN-2 | Inhibition of SHMT1 and SHMT2. | Preclinical | 26, 27 |

| FA metabolism and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 12 | Dehydrocurvularin | ATP citrate lyase inhibition. | Preclinical | 28 |

| 13 | Bezafibrate + medroxyprogesteron acetate | Prostaglandin inhibition. | In vitro | 29, 30 |

| 14 | Statin-dipyridamole | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor/MVA biosynthesis inhibition. | Preclinical | 31 |

| 15 | Statin + (venetoclax or navitoclax) | MVA biosynthesis inhibition, BCL-2 and BCL-XL inhibitor, and upregulation of the p53 protein. | In vitro | 32 |

| 16 | Statin | MVA biosynthesis inhibition; upregulation of the p53 protein and isoprenylation of the Rho and Ras GTPases. | Phase 2 | 33 |

| 17 | LCL204 | Ceramide inhibition. | Preclinical | 34 |

| Nucleotide metabolism and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 18 | 6-thioguanine | PRPP amidotransferase inhibitor. | Clinical trials | 35 |

| 19 | FF-10501 | IMPDH inhibitor/inhibit purine metabolism. | Phase 1 (#NCT02193958) | 36, 37 |

| 20 | Ara-C, gemcitabine | Pyrimidine analog/inhibit nucleotide biosynthesis. | FDA approved | 38 |

| 21 | BAY-2402234 ASLAN003 PTC299 | Dihydrofolate dehydrogenase inhibition. | Phase 1 (#NCT03404726) Phase 2 (#NCT03451084) Phase 3 (#NCT03761069) | 39, 40, 41 |

| 22 | 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-O-monophosphate[10] | Thymidylate synthetase (TS) inhibitor/reduce thymidine nucleotide. | Preclinical | 42 |

| Glycolytic and mitochondrial OXPHOS and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 23 | 2,5-anhydro-D-mannitol + Ara-C | Fructose analog/inhibit GLUT5. | Preclinical | 43 |

| 24 | 2-DG | HK/glycolytic pathway; compete with glucose and phosphorylated into 2-DG-6-P. | Preclinical | 44, 45, 46 |

| 25 | 3-PO | PFKFB3 inhibitor/glycolytic pathway; suppressed glucose uptake and decreased intracellular lactate levels. | Preclinical | 47 |

| 26 | TT-232 | PKM2 inhibitor/glycolytic pathway; induced apoptosis and promoted autophagy. | Preclinical | 48 |

| 27 | CPI-613 (devimistat) | PDH and αKG-dehydrogenase complexes inhibition/TCA cycle. | Phase 3 (#NCT03504410) | 49 |

| 28 | 2,2-dichloroacetophenone | Inhibits PDK1, increased the activation of proapoptotic protein (PARP and caspase 3), decreased the expression of antiapoptotic protein (BCL-XL, BCL-2). | Preclinical | 50 |

| 29 | Ivosidenib (AG-120) Enasidenib (AG221) | IDH1 inhibitor; reduce 2-HG IDH2 inhibitor and 2-HG synthesis. | FDA approved | 6, 7, 51 |

| 30 | ABT-737, ABT-264 | OXPHOS inhibition. | In vitro | 52 |

| 31 | Venetoclax + azacitidine | TCA cycle and OXPHOS inhibition. | FDA approved | 11, 53 |

| 32 | 2′3′-dideoxycytidine | mtDNA polymerase γ inhibition, inhibition of mtDNA replication and OXPHOS. | Preclinical | 54, 55 |

| 33 | 2-C-methyladenosine | Inhibition of OXPHOS and termination of mitochondrial transcription. | Preclinical | 56 |

| Vitamins and therapeutic drugs | ||||

| 34 | Vitamin C | Cofactor of Fe2+ and αKG-dependent dioxygenases, promotes TET2 activity to limit HSPC self-renewal and leukemogenesis. | Clinical trials (#NCT03526666 and #NCT02877277) | 57, 58, 59 |

| 35 | Isoniazid, 4′-O-methoxypyridoxine | Inhibition of PLP/pyridoxal kinase activity. | Preclinical | 60 |

| 36 | ATRA + arsenic trioxide | Overcome the differentiation arrest through transcriptional de-repression and degradation of PML-RARA. | Phase 3 (#NCT00482833) | 61 |

| Resistance mechanisms to the current treatment | ||||

| 37 | Venetoclax + azacitidine + tedizolid | Inhibition of mitochondrial translation. | Preclinical | 62 |

| 38 | Venetoclax + ibrutinib Venetoclax + cobimtinib | OXPHOS and Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibition. OXPHOS and MEK inhibition. | Preclinical | 63, 64 |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; SAHH, S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase.

BCAAs

BCAAs (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) are essential for cancer growth. Functionally, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are highly sensitive to valine; perturbation of valine levels imbalances BCAAs and reduces the proliferation and survival of HSCs.65 Taya et al showed that HSCs fail to proliferate when cultured in valine-exhausted conditions.66 Accordingly, dietary valine restriction was sufficient to condition murine bone marrow for HSC transplantation, allowing for donor cell engraftment. Through high-resolution proteomics analysis, Raffel et al demonstrated that human AML stem cells (as compared with non–stem cell populations) were enriched for the BCAA pathway with overexpression of branched-chain amino acid transaminase 1 (BCAT1).67 BCAT1 knockdown resulted in the accumulation of α-ketoglutarate (αKG), degradation of HIF1α by EGLN1 (an αKG-dependent hydroxylase), and impaired leukemogenesis. Conversely, BCAT1 overexpression in leukemic cells depleted intracellular αKG, abrogated ten-eleven translocation (TET; an αKG-dependent dioxygenase) activity, and enhanced DNA hypermethylation. Given convergence on αKG homeostasis, a link between BCAT1 and IDH mutational status was explored. High BCAT1 expression correlated with shorter survival in IDHWTTET2WT but not in IDHmut or TET2mut AML, presumably reflecting the relative insensitivity of AML harboring these mutations to αKG perturbation.67 Collectively, these experiments suggest that the BCAA-BCAT1 pathway may represent a point of therapeutic opportunity. Gabapentin, an anticonvulsant drug with some inhibitory activity toward BCAT1, efficiently suppressed the clonal proliferation of primary human AML cells.15

Methionine

Methionine is a critical component of the 1-carbon metabolism. Biochemically, methionine is converted to S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) by isoenzymes of the methionine adenosyl transferase family. SAM then serves as a methyl donor for the modification of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids in a reaction catalyzed by SAM-dependent methyltransferases. A recent study by Cunningham et al examined amino acid dependencies in primary AML leukemic stem cells (LSCs) and demonstrated the dependence on methionine (as well as lysine, arginine, glutamine, and cysteine).68 Importantly, dietary methionine starvation delayed patient-derived xenograft (PDX) progression. Mechanistically, methionine was required for the generation of SAM to provide methyl groups for histone methylation. The inhibition of SETD2 (a H3K36-specific methyltransferase) exerted antileukemic effects and may serve as a therapeutic approach to exploit methionine dependency. Alternative approaches include targeting the methionine adenosyl transferase family directly (Table 1).16

Tryptophan

Beyond its use in protein synthesis, most of the remaining dietary tryptophan is metabolized via the kynurenine pathway, the first and rate-limiting step of which is catalyzed by either indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) or tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase. Immunosuppressive effects of IDO and kynurenine in cancer and preventing effector T-cell activation and inhibiting natural killer cell function are well described.17 Accordingly, high levels of serum kynurenine were independently predictive for shorter overall survival in patients with AML.69 Mechanistically, IDO is constitutively expressed in primary AML blasts, resulting in kynurenine secretion and suggesting a possible means of AML escape from immune surveillance.18 IDO inhibitors such as indoximod (1MT), epacadostat (INCB024360), and linrodostat (BMS986205) have undergone varying degrees of early clinical testing in AML (Table 1).

Nonessential amino acids

Eleven proteinogenic amino acids are normally synthesized by cells and considered nonessential. They play key roles in cancer metabolism by managing oxidation-reduction potential, contributing to macromolecule biosynthesis, and participating in signaling.70 Here, we review nonessential amino acids with established roles in AML biology and related metabolic targets (Figure 1; Table 1).

Glutamine

Glutamine is produced de novo by lysosomal degradation of proteins or imported by the glutamine transporter, SLC1A5. It can then be converted intracellularly into glutamate and subsequently αKG by the enzymes glutaminase (GLS) and glutamate dehydrogenase, respectively. In the reverse set of reactions, glutamine is produced from the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, in which αKG is converted into glutamate and then glutamine through the activity of glutamine synthase (GS). Glutamine serves as a carbon source for oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), and its involvement in anaplerosis is reinforced by data showing that derivative metabolites such as αKG, oxaloacetate, and pyruvate help actively dividing cancer cells survive in the context of glutamine deprivation.71 Instead, the production of glutamine-derived metabolites such as fumarate, malate, and citrate increases when glucose is limited.

In AML cells, glutamine deprivation inhibits target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling and induces apoptosis.72 This is thought in part due to the activity of bidirectional transporter SCL7A5/SCL3A2, which exchanges intracellular glutamine for leucine. Intracellular leucine, in turn, regulates amino acid/Rag/mTORC1 signaling by activating Ras-related GTPases, which enable mTORC1 localization in proximity to its activator, Rheb. Leucine depletion limits this Rheb-mediated mTOR activation and inhibits growth.73

Inhibition of GLS or SLC1A5 (a glutamine transporter) has been investigated as a therapeutic approach. In fact, knockdown of SLAC1A5 was shown to inhibit tumor formation in a xenotransplantation model of AML.72 In addition, the antineoplastic agent, L-asparaginase (ASNase; discussed further in the Asparagine section), harbors “off-target” antileukemic GLS activity74-76 and upregulates GS expression in leukemic cells.72 Knockdown of GS enhances the apoptotic and autophagic activity of ASNase in AML, implicating combinatorial GLS activity/glutamine uptake inhibition as a therapeutic strategy. GLS inhibitors such as CB-839 and BPTES also demonstrate antileukemic activity19 (Table 1).

Asparagine

Asparagine is synthesized by the transamination of aspartate and glutamine into asparagine and glutamate, respectively, catalyzed by asparagine synthetase (ASNS). In cancer cells, asparagine suppresses apoptosis and promotes cellular adaptation to glutamine deprivation without restoring TCA cycle intermediates.75 In fact, knockdown of ASNS can induce apoptosis in cancer cells even in the presence of glutamine. ASNase instead deaminates and depletes asparagine (and glutamine), leading to impaired protein translation and nucleotide synthesis. Clinical studies over the years have examined ASNase in AML, with some evidence of efficacy offered, for example, in combination with cytarabine.20 However, ASNase has not become a mainstay of treatment, with reduced sensitivity in AML compared with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), possibly attributable to variable ASNS levels.77 Toward improving the efficacy of ASNase in AML, 1 study found that activation of Wnt-dependent stabilization of proteins (STOP) could improve its therapeutic index by inhibiting GSK3-dependent protein ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.78

Arginine

Arginine is a conditionally essential amino acid, synthesized from citrulline by argininosuccinate synthetase-1 and arginosuccinate lyase. Under certain circumstances, cancer cells receive arginine from an external diet and import it using cationic amino acid transporters (CATs).79 Importantly, AML blasts lack argininosuccinate synthetase-1, making them auxotrophic for arginine. They instead import arginine using constitutively expressed arginine transporters CAT-1 and CAT-2B.80 Rapid depletion of arginine using BCT-100, a pegylated human recombinant arginase, leads to decreased AML proliferation and engraftment after transplantation in xenograft models.21 Further, BCT-100 synergizes with cytarabine to exert cytotoxic effects on AML blasts isolated from patients. Functionally, AML blasts alter the immune microenvironment by releasing arginase II into the plasma, resulting in T-cell inhibition and HSC proliferation.81 Miraki-Moud et al demonstrated that depletion of intracellular arginine using ADI-PEG20, a mycoplasma-derived arginine deaminase, reduces AML burden in PDXs, an effect potentiated by combination with cytarabine.22

Cysteine

Cysteine serves as a precursor for the biosynthesis of reduced glutathione (GSH). Due to high metabolic rates and the activity of certain oncogenes in cancer, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) are increased and result in oxidative stress. To counterbalance ROS and maintain intracellular redox potential, cancer cells enhance the production of reduced GSH (Figure 1). These cells take up extracellular cysteine through the disulfide L-cysteine (CSSC)/glutamate-based xCT antiporter. Thus, therapeutic strategies have been identified to suppress the import of extracellular cysteine. One such strategy is the engineering of “cyst(e)inase,” a modified version of human cystathionine-γ-lyase. In multiple tumor models, cyst(e)inase reduced extracellular L-cysteine and CSSC pools, depleted intracellular GSH, enhanced ROS, and induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.23

In AML, LSCs rely uniquely on amino acids, including cysteine, for OXPHOS and cell survival.13 In this context, cysteine depletion leads to reduced GSH levels and loss of glutathionylation of succinate dehydrogenase A, a crucial subunit of electron transport chain complex II. The resultant decrease in OXPHOS and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation impairs LSC survival.82 These studies expand on earlier work showing that CD34+ AML blasts have lower levels of reduced GSH and increased levels of oxidized GSH compared with their normal CD34+ counterparts. The use of the compound parthenolide, which reacts with accessible cysteines containing free thiols and depletes GSH, induces cell death in part through oxidative stress (Table 1).24

Serine and glycine

The biosynthesis of serine and glycine are interconnected. Serine is synthesized de novo from 3-phosphoglycerate and glutamate through the activity of 3 enzymes, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), phosphoserine aminotransferase 1, and phosphoserine phosphatase. De novo synthesis of glycine from serine is catalyzed by serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT1 and SHMT2) (Figure 1).83 Serine and glycine are indispensable for several metabolic pathways that facilitate oncogenesis.84 In AML, silencing of PHGDH or serine-deprivation exerted antileukemic effects.85 Additionally, WQ-2101, a small molecule of PHGDH, inhibited proliferation of FLT3–internal tandem duplication (ITD) AMLs and sensitized them to cytarabine.25 Inhibitors targeting SHMT, although not extensively studied in AML, have shown efficacy in T-cell ALL models26,27 and merit further investigation in myeloid disease.

Lipid metabolism and AML

Lipids and their derivatives are essential for energy production and as structural components of cellular and organelle membranes. Here, we review roles for several categories of lipids, including fatty acids (FAs), sterols, isoprenoids, and sphingolipids, in the pathophysiology of AML (Figure 2; Table 1).

FA metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. Schematic representation showing the transport of citrate into the cytoplasm, conversion to acetyl-CoA, and generation of FA intermediates through either downstream carboxylation or alternatively through the MVA pathway. Enzymes with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue. Chemical inhibitors or gene silencing effects are highlighted in red. ACC, acetyl Co-A carboxylase; ACLY, ATP citrate lyase; DCV, dehydrocurvularin; FASN, fatty acid synthase; HMGCR, HMG-CoA reductase; ME1, malic enzyme 1; OAA, oxaloacetate; SCD1, stearoyl CoA desaturase 1.

FA metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. Schematic representation showing the transport of citrate into the cytoplasm, conversion to acetyl-CoA, and generation of FA intermediates through either downstream carboxylation or alternatively through the MVA pathway. Enzymes with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue. Chemical inhibitors or gene silencing effects are highlighted in red. ACC, acetyl Co-A carboxylase; ACLY, ATP citrate lyase; DCV, dehydrocurvularin; FASN, fatty acid synthase; HMGCR, HMG-CoA reductase; ME1, malic enzyme 1; OAA, oxaloacetate; SCD1, stearoyl CoA desaturase 1.

FAs

Under normal conditions, de novo FA synthesis is repressed in adult tissues and dietary lipids are preferred for structural use. In contrast, dividing AML cells rely on FAs to support membrane biogenesis, increased biomass, lipoprotein generation, and importantly, energy production through β-oxidation.86,87 Therefore, FA metabolism represents an appealing therapeutic target. Some cancer cells preferentially utilize fatty acid oxidation (FAO), which generates 2.5 times more ATP per mole as compared with glucose oxidation, and express high levels of the required enzymes. A rate-limiting enzyme in the FAO pathway, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1a, was validated as a therapeutic target in AML.88 Similarly, carnitine transporter CT2, a membrane transporter that takes up carnitine (a cofactor for FAO), was shown to be overexpressed in certain AML lines, rendering them susceptible to CT2 short hairpin RNA–induced cytotoxicity.89 FA biosynthesis also represents a possible therapeutic target. For instance, high expression of ATP citrate lyase, which catalyzes the conversion of citrate to acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) for FA synthesis, is associated with worse overall survival in AML.90 Dehydrocurvularin, a fungal macrolide product, was thus identified through chemoproteomic profiling as an ATP citrate lyase inhibitor and candidate antineoplastic agent.28 Additional studies examined FA biogenesis in AML using mass spectrometry–based lipidomics.91 Through these methods, lipogenic enzymes, including stearoyl CoA desaturase 1, were shown to be effectors of AML cell death induced by a combination drug treatment of bezafibrate and medroxyprogesterone acetate, previously suggested to have antileukemic activity.29 However, significant clinical benefit from this combination therapy has not yet been appreciated.30

Sterols and isoprenoids

Produced from acetyl-CoA using the mevalonate (MVA) pathway (Figure 2), sterols and isoprenoids are vital for membrane structure, cell growth, and differentiation. Certain agents, such as statins and bisphosphonates, inhibit the MVA pathway and have been suggested to exert antineoplastic activity. Statins prevent the conversion of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) to MVA by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase.92 Evidence for antileukemic statin effects has existed for some time, as lovastatin was shown to induce apoptosis and upregulate differentiation markers in AML cell lines.93 More recently, through a compound screen for statin potentiators, Pandyra et al demonstrated that the antileukemic effects of statins could be enhanced by combination with dipyridamole, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor.31 Isoprenoid synthesis, dependent on the MVA pathway, is required for the function of oncogenic proteins such as Ras and the BCL-2. Through their inhibition of MVA production and downstream protein geranylgeranylation, a form of prenylation, statins increased the proapoptotic activity of venetoclax and navitoclax.32 Separately, statins were found to interfere with isoprenylation of the Rho and Ras GTPases, implicating Ras-MEK-ERK signaling in their mechanism of action.94 Clinically, statins were examined in a phase 2 study in combination with chemotherapy in relapsed/refractory AML, demonstrating a 75% complete recovery (CR) + CR with incomplete count recovery rate.33 However, this degree of efficacy was not appreciated in poor-risk AML groups.95 Ultimately, a prospective randomized trial (vs conventional therapy) will be required to evaluate the benefit of a statin-containing regimen.

Sphingolipids

Bioactive sphingolipids, including ceramides, dihydroceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), are responsible for cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and signal transduction.96 Biochemically, ceramides are generated by ceramide synthase and cleaved by acid ceramidase (AC). Tan et al demonstrated that high levels of AC expression in primary AML cells result in antiapoptotic MCL-1 activity, increased S1P levels, and decreased ceramide levels. Accordingly, treatment with the AC inhibitor LCL204 reduced AML cell viability and conferred a survival benefit to PDX-recipient mice.34 Sphingosine kinase 1, which generates S1P from sphingosine, was found to be overexpressed and constitutively active in AML.97 Targeting sphingosine kinase 1 induced apoptosis in AML blasts and LSCs isolated from patients. Further evidence links ceramide biology to the activity of AML oncogenes. For instance, FLT3-ITD mutations have been associated with suppressed generation of pro–cell death ceramides.98 FLT3 inhibition reactivated ceramide generation in AML cells and induced ceramide-dependent mitophagy and cell death.

Nucleotide metabolism and AML

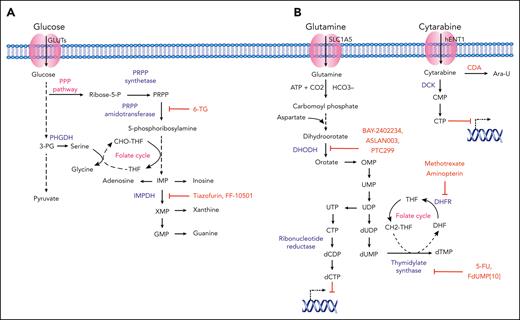

Indispensable for actively dividing cells, purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis are achieved either de novo or through salvage pathways (Figure 3). Using 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP), de novo pathway enzymes essentially build purine and pyrimidine nucleotides from “scratch” using simple molecules such as CO2, amino acids, and tetrahydrofolate. Certain exogenous nucleoside analogs and nucleobases (often termed antimetabolites) structurally resemble physiological purines and pyrimidines and serve as potential chemotherapeutic agents in leukemia. Functionally, nucleoside analogs such as cytarabine mimic endogenous nucleosides and integrate into newly synthesized DNA, leading to the block and termination of DNA synthesis. Nucleoside analogs also inhibit enzymes involved in purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis, leading to apoptosis through caspase activation.99,100

Nucleotide metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. (A) Purine nucleotide biosynthesis in AML. Schematic representation showing purine synthesis through the utilization of glycolytic intermediates. Key enzymes, inhibitory compounds, and metabolic pathways with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue, red, and pink, respectively. (B) Pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthesis in AML. Schematic representation showing the key enzymes involved in de novo pyrimidine synthesis. The transport of pyrimidine analog cytarabine and the mechanistic inhibition of DNA synthesis in leukemic cells is represented. Different enzymes, inhibitory compounds, and metabolic pathways with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue, red, and pink, respectively. Ara-U, uracil arabinoside; CDP, cytidine diphosphate; CMP, cytarabine monophosphate; CTP, cytidine triphosphate; DHF, dihydrofolate; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; DOODH, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; GMP, guanine monophosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; IMPDH, 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase; OMP, orotidine 5′-monophosphate; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PHGDP, 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; 6-TG; 6-thioguanine; UMP, uridine monophosphate; TS, thymidylate synthase; UDP, uridine diphosphate; UTP, uridine triphosphate; XMP, xanthine monophosphate.

Nucleotide metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. (A) Purine nucleotide biosynthesis in AML. Schematic representation showing purine synthesis through the utilization of glycolytic intermediates. Key enzymes, inhibitory compounds, and metabolic pathways with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue, red, and pink, respectively. (B) Pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthesis in AML. Schematic representation showing the key enzymes involved in de novo pyrimidine synthesis. The transport of pyrimidine analog cytarabine and the mechanistic inhibition of DNA synthesis in leukemic cells is represented. Different enzymes, inhibitory compounds, and metabolic pathways with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue, red, and pink, respectively. Ara-U, uracil arabinoside; CDP, cytidine diphosphate; CMP, cytarabine monophosphate; CTP, cytidine triphosphate; DHF, dihydrofolate; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; DOODH, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; GMP, guanine monophosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; IMPDH, 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase; OMP, orotidine 5′-monophosphate; 3-PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PHGDP, 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; 6-TG; 6-thioguanine; UMP, uridine monophosphate; TS, thymidylate synthase; UDP, uridine diphosphate; UTP, uridine triphosphate; XMP, xanthine monophosphate.

Purines

Purine analogs, such as cladribine and fludarabine, have been used routinely in the treatment of chronic leukemias such as hairy cell leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, respectively. Additional purine analogs such as 6-thioguanine and 6-mercaptopurine have been examined in the context of AML and acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), respectively.35,101 Among their targets in purine biosynthesis are PRPP amidotransferase and inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) (Figure 3A). In leukemia, prior work showed that the nucleoside analog tiazofurin could inhibit IMPDH activity in myeloid blasts, an effect potentiated in combination with chemotherapy.102 More recently, in human AML cell lines and bone marrow cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndrome, FF-10501, an oral competitive inhibitor of IMPDH, was shown to decrease leukemic proliferation, induce differentiation, and maintain efficacy in the context of azacitidine resistance.36,37

Pyrimidines

Cytarabine, an analog of deoxycytidine, inhibits DNA synthesis and is used extensively in the treatment of AML. Other pyrimidine analogs, such as gemcitabine, have well-established efficacy in solid tumors and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma but limited activity in AML.38 Metabolism-based resistance to cytarabine is discussed below. Regarding novel therapies, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, a key enzyme for de novo pyrimidine synthesis, was identified as a putative AML target in a high-throughput phenotypic screen to identify compounds (and their corresponding biological targets) capable of driving myeloid differentiation.103 Subsequently, analyses of potent dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors such as BAY2402234, ASLAN003, and PTC299 were shown to induce differentiation induction across multiple AML subtypes.39-41 All 3 agents are being evaluated in clinical trials for relapsed/refractory AML (#NCT03404726, #NCT03451084, and #NCT03761069). 5-fluorouracil is a synthetic analog of uracil that inhibits thymidylate synthetase. It is not used commonly in hematologic malignancies due to lack of evidence for efficacy and overlapping toxicity with standard therapies. However, a novel fluoropyrimidine, 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-O-monophosphate, was demonstrated to target thymidylate synthetase as well as topoisomerase I, exerting antileukemic effects in AML models.42 Finally, folate analogs, such as methotrexate, act as competitive inhibitors of dihydrofolate reductase, which generates tetrahydrofolate required for de novo thymidine synthesis. Although methotrexate is used commonly in ALL therapy, it has a limited role in treating myeloid disease. Additional folate analogs such as aminopterin have not demonstrated efficacy in AML.104

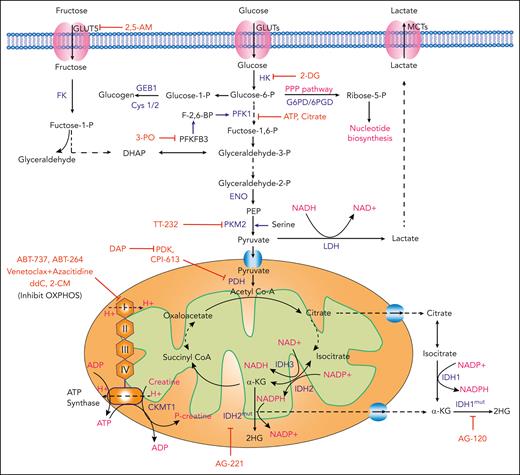

Glycolytic metabolism and AML

Through glycolysis, 1 molecule of glucose is converted into 2 molecules of pyruvate, generating ATP and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). Pyruvate may then be converted into lactate or enter the TCA cycle (Figure 4). Normal cells rely primarily on mitochondrial OXPHOS to generate ATP, but cancer cells increasingly favor aerobic glycolysis, whereby energy is produced through glycolysis followed by lactate fermentation, even in the presence of oxygen.105 Based on the 1924 observations of Otto Warburg, this phenomenon has been termed the “Warburg effect.” By providing biosynthetic precursors in the form of glycolytic intermediates, this mode of energy production, inefficient compared to OXPHOS, supports the production of macromolecules required for cancer proliferation.105

Glycolysis and mitochondrial OXPHOS in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. Schematic representation showing the cellular uptake and downstream utilization of glucose and fructose. Enzymes with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue. Chemical and biological inhibitors are highlighted in red. Biological outputs and metabolic pathways are highlighted in pink. 2,5-AM, 2,5-anhydro-D-mannitol; FK, fructose kinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCTs, monocarboxylate transporters; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

Glycolysis and mitochondrial OXPHOS in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. Schematic representation showing the cellular uptake and downstream utilization of glucose and fructose. Enzymes with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue. Chemical and biological inhibitors are highlighted in red. Biological outputs and metabolic pathways are highlighted in pink. 2,5-AM, 2,5-anhydro-D-mannitol; FK, fructose kinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCTs, monocarboxylate transporters; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

Highlighting the therapeutic implications of glycolytic metabolism in AML, independent studies have shown that upregulated glycolysis correlates with resistance to chemotherapeutic agents in vitro.106,107 Interestingly, however, the prognostic implications of increased glycolytic metabolism have been discrepant. For instance, Herst et al reported that high levels of aerobic glycolysis in AML blasts at diagnosis were predictive for improved therapy response and survival in a small series of patients.106 In contrast, Chen et al, by comparing metabolomic profiles of serum samples from 400 patients with AML with those from 446 healthy controls, were able to generate a prognosis risk score based on 6 metabolites that correlated inversely with glycolysis and survival (ie, low prognosis risk score was associated with enhanced glycolysis by gene expression and poor survival).107

GLUTs

Cellular glucose (and fructose) uptake is mediated by transporters such as glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) and GLUT5 in AML.108 During glucose deprivation (and presumably due to increased glucose consumption in leukemic bone marrow),109 AML cells preferentially take up fructose, a process facilitated by increased expression of fructose transporter GLUT5 (encoded by the SLC2A5 gene) in AML as compared with normal monocytes.43 In fact, increased SLC2A5 expression or fructose utilization was associated with poor outcomes in patients. Importantly, the fructose analog 2,5-anhydro-D-mannitol suppressed leukemic proliferation in low glucose conditions and synergized with cytarabine.43

HK

Hexokinase (HK) catalyzes the first rate-limiting step in glycolysis. Accordingly, studies have investigated 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), a glucose analog that inhibits glycolysis, induces oxidative stress, inhibits N-linked glycosylation, and activates autophagy.44 Biochemically, 2-DG competes with glucose for uptake by GLUTs and is subsequently phosphorylated into 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate (2-DG-6-P) by HK. 2-DG-6-P, which cannot be further metabolized by phosphoglucose isomerase, accumulates intracellularly to inhibit glycolysis through both competitive and noncompetitive inhibition of phosphoglucose isomerase and HK, respectively.44,45 Larrue et al assessed the effect of 2-DG in AML cell lines, where they showed it to modulate the cell-surface expression and activity of oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases.46 Treatment of primary human AML cells with 2-DG in vitro reduced proliferation, promoted apoptosis, and synergized with BCL-2 inhibition.110 Phase 1 studies of 2-DG in solid tumors demonstrated tolerability of the agent alone and in combination with chemotherapy. Toxicities included hypoglycemia and dose-limiting corrected QT interval (QTc) prolongation, an electrocardiogram abnormality.111,112 Phase 2 studies were initiated but terminated due to poor accrual, so efficacy remains unknown.

PFK1

Phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1) catalyzes the first committed and rate-determining step in glycolysis and is subject to complex catalytic and allosteric regulation by cellular metabolites, including adenosine monophosphate; adenosine diphosphate (ADP); ATP; fructose 2,6-bisphosphate; and citrate, among others. Anaplerotic conditions result in elevated intracellular levels of citrate, an allosteric inhibitor of PFK1, to slow glycolysis.113 PFK1 is activated at a separate allosteric site by fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (F-2,6-BP). F-2,6-BP is both generated and subsequently degraded by the bifunctional enzyme (kinase/phosphatase) phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase (PFKFB).114 Among 4 PFKFB isoenzymes in mammals, PFKFB3 (which has only kinase activity) has been shown relevant to tumor cell glycolysis.115 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one, a computationally identified inhibitor of PFKFB3, suppresses glucose uptake, decreases intracellular lactate levels, and inhibits AML proliferation in vitro and in xenotransplantation.47

PK

The third rate-limiting glycolytic enzyme, pyruvate kinase (PK) converts phosphoenolpyruvate and ADP to pyruvate and ATP. Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), 1 of 4 PK isozymes expressed in cells, is a key regulator of glycolysis in AML, in which its expression is inversely correlated with survival in patients with NPM1 mutations.116,117 PKM2 silencing seems to induce apoptosis and promote autophagy in AML cell lines, although the precise mechanism mediating the latter requires further elucidation.116 Nonetheless, this provides a rationale for targeting PKM2 therapeutically in NPM1-mutated AML. Interestingly, TT-232, a synthetic derivative of the peptide hormone somatostatin, was found to target PKM2 (in addition to somatostatin receptors SSTR1 and SSTR4) and inhibit the growth of leukemia cell lines and xenograft models.48 Although somatostatin receptors have themselves been implicated in AML pathogenesis,118,119 the dual specificity of TT-232 raises the possibility that PKM2 may also represent a therapeutic target.

Mitochondrial metabolism and AML

PDH

Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) serves to link FA metabolism, glycolysis, and the TCA cycle by converting pyruvate, coenzyme A, and NAD+ into acetyl-CoA, NADH, and CO2. Since studies have shown that high ROS levels, increased mitochondrial mass, and high OXPHOS may serve as a mechanism of resistance to chemotherapy, new strategies have emerged to target mitochondrial metabolism, and specifically, PDH (Figure 4). The drug CPI-613 (also known as devimistat), is an analog of lipoate, a catalytic cofactor, and modulator of several enzymes including PDH as well as the αKG-dehydrogenase complex and others involved in amino acid catabolism.120-122 Based on preclinical data showing that PDH inhibition sensitizes AML cells to treatment with chemotherapy, phase 1/2 studies of CPI-613 in combination with chemotherapy were performed.49,123 The combination was relatively well tolerated, with encouraging CR rates nearing 50%, even in elderly patients and those with poor cytogenetics. However, a phase 3 study of high-dose chemotherapy with or without CPI-613 in older patients with recurrent or persistent AML (#NCT03504410) was stopped due to futility.49

PDK

Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) inhibits PDH by ATP-dependent phosphorylation of 3 serine residues (Ser-264, Ser-271, and Ser-203) of the α (E1) subunit of the PDH complex. This inhibition of PDH uncouples glycolysis from glucose oxidation, thus, increasing pyruvate metabolism in the cytosol with a concomitant decrease in its mitochondrial oxidation.124,125 Qin et al showed that 2,2-dichloroacetophenone inhibits PDK1, blocking AML proliferation in vitro and in subcutaneous injection–based xenografts.50 Notably, 2,2-dichloroacetophenone treatment increased the activation of proapoptotic proteins [poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and caspase 3] and decreased the expression of antiapoptotic proteins (BCL-XL and BCL-2), suggesting PDK1 may serve as a therapeutic target in AML.

IDH

The IDH family of enzymes comprises cytoplasmic and peroxisomal IDH1 and mitochondrial IDH2 and IDH3. Importantly, recurrent missense mutations in the IDH1 and IDH2 genes are found in ∼20% of AML cases.126 The pathogenesis of IDH mutations in leukemia has been extensively reviewed.127-129 To summarize briefly, under physiologic conditions, IDH1 and IDH2 catalyze the NADP+-dependent oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate to αKG (Figure 4).130 Oncogenic IDH mutations instead confer a neomorphic activity, catalyzing the reduction of αKG to the (R) enantiomer of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), which in turn functions as a competitive inhibitor of αKG-dependent dioxygenases to facilitate leukemogenesis.131-137 One such αKG-dependent effector of mutant IDH is the AML tumor suppressor Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (TET2; discussed further in “Vitamin Metabolism and AML”), whose inhibition by (R)-2-HG results in global DNA hypermethylation and impaired myeloid differentiation.133 Importantly, ivosidenib (AG-120, a mutant IDH1 inhibitor) and enasidenib (AG-221, a mutant IDH2 inhibitor) are Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of IDH1-mutant and IDH2-mutant AML, respectively, based on successful phase 1/2 clinical trials.6,7,51 Studies investigating mechanisms of resistance to mutant IDH inhibition have identified cases in which mutations arise either in trans or cis at the IDH dimer interface (where the drug binds) in the targeted enzyme.138 Isoform switching, whereby, for instance, mutations in IDH2 arise after therapy targeting mutant IDH1, is also reported.139 Quite interestingly, the (S) enantiomer of 2-HG is physiologically induced in hematopoietic cells under conditions of hypoxia by lactate dehydrogenase and malate dehydrogenase, rather than IDH.140,141 Also capable of inhibiting αKG-dependent dioxygenases,142 these studies suggest that (S)-2-HG may play a role in the adaptation of malignant cells to hypoxic stress.

Mitochondrial OXPHOS

OXPHOS is essential to produce ATP required to increase biomass and meet the energy demands of malignant cells. AML cells, compared with normal HSPCs, have increased mitochondrial mass without a compensatory increase in respiratory chain complex activity.143 As such, they exhibit lower spare reserve capacity in the respiratory chain, which enhances their sensitivity to oxidative stress. Importantly, maintenance of LSC function and quiescence in the bone marrow niche also depends on redox homeostasis. Lagadinou et al determined that LSCs are functionally characterized by low levels of ROS, attributable to a low, yet necessary, level of OXPHOS without a compensatory increase in glycolysis.52 Further, they found that BCL-2 is highly upregulated in ROS-low LSCs and that its inhibition with compounds such as ABT-737 and ABT-264 (navitoclax) can reduce OXPHOS and induce LSC cell death without affecting normal HSCs.52 Based on this work, Pollyea et al showed that the use of venetoclax plus azacitidine in patients with AML disrupted the TCA cycle, inhibited electron transport chain complex II, and suppressed OXPHOS in LSCs.53 Clinically, the combinations of venetoclax and HMAs have proven successful, initially in phase 1b studies,10,144 and most recently in a phase 3 trial of venetoclax plus azacitidine with CR + CR with incomplete count recovery rates of 66.4% (vs 28.3% for placebo plus azacitidine, P < .001), leading to Food and Drug Administration approval.11

mtDNA

Studies have examined mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) biosynthesis in the context of AML. Gene expression profiling from 542 human AML patient samples demonstrated upregulation of the mtDNA biosynthesis pathway in a large proportion of AML as compared to normal hematopoietic cells.145 This finding is in accordance with the long-standing observation that mtDNA is amplified in AML.54 Knock down of cytoplasmic nucleoside kinases, which are increased in AML and support mitochondrial nucleotide generation, reduced mtDNA levels.145 Importantly, 2′3′-dideoxycytidine, a nucleoside analog and inhibitor of mtDNA polymerase γ, selectively targeted AML through inhibition of mtDNA replication and OXPHOS.54,55 Related efforts have instead targeted the mitochondrial RNA polymerase using 2-C-methyladenosine, a terminator of mitochondrial transcription (Table 1).56 As with 2′3′-dideoxycytidine, treatment of mice with 2-C-methyladenosine demonstrated efficacy against xenografted human AML cell lines without significant toxicity.56

Vitamin metabolism and AML

Vitamin C and TET activity

Certain AML subsets are characterized by abnormal DNA methylation patterns that probably silence the expression of tumor suppressor genes. TET2, a member of the TET family of αKG-dependent dioxygenases, facilitates DNA demethylation by converting 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (Figure 5A). Mutations in TET2 occur in ∼10% of AML cases and result in increased methylation at gene promoters.146 Moreover, mutations in IDH1, IDH2, and WT1 (encoding Wilms tumor protein 1) directly impact TET2 activity.147 Together, genetic alteration of the IDH-TET2-WT1 axis is appreciated in 30% to 50% of AML cases.148 As described above, mutant IDH catalyzes formation of the oncometabolite (R)-2-HG, which acts as a competitive inhibitor of TET2 and contributes to leukemogenesis. Therefore, it has been suggested that restoration of TET2 function could benefit patients with AML therapeutically.

Vitamin metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. (A) Regulation of TET enzymes by vitamin C (ascorbate). Schematic representation demonstrating the ascorbate-dependent regulation of the TET enzymes by ascorbate, as well as downstream epigenetic effects in HSCs (multipotent progenitors [MPPs]) and cancer stem cells. (B) Regulation of vitamin B6 (pyridoxal) in AML. Schematic representation of pyridoxal uptake and downstream utilization in AML cells, including a central role for PLP and downstream effector enzymes, ODC1 and GOT2 in leukemic proliferation. Enzymes and inhibitory compounds with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue, and red, respectively. BER, base exclusion repair; 5CaC, 5-carboxylcytosine; 5fC, 5-formyl cytosine; DHA, dehydroascorbate; GOT2, glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 2; 5mC, 5-methylcytosine; 5hmC, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine; ODC1, ornithine decarboxylase.

Vitamin metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. (A) Regulation of TET enzymes by vitamin C (ascorbate). Schematic representation demonstrating the ascorbate-dependent regulation of the TET enzymes by ascorbate, as well as downstream epigenetic effects in HSCs (multipotent progenitors [MPPs]) and cancer stem cells. (B) Regulation of vitamin B6 (pyridoxal) in AML. Schematic representation of pyridoxal uptake and downstream utilization in AML cells, including a central role for PLP and downstream effector enzymes, ODC1 and GOT2 in leukemic proliferation. Enzymes and inhibitory compounds with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue, and red, respectively. BER, base exclusion repair; 5CaC, 5-carboxylcytosine; 5fC, 5-formyl cytosine; DHA, dehydroascorbate; GOT2, glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 2; 5mC, 5-methylcytosine; 5hmC, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine; ODC1, ornithine decarboxylase.

Two noteworthy studies demonstrated that vitamin C, a cofactor of Fe2+- and αKG-dependent dioxygenases, promotes TET activity to limit HSPC self-renewal and leukemogenesis.149,150 Vitamin C depletion was shown to cooperate with FLT3-ITD mutations to promote HSC expansion and leukemogenesis, whereas vitamin C treatment suppressed leukemogenesis, mimicking TET2 reactivation.149,150 Because the oxidation products of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, such as 5-formyl cytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine, recruit base excision repair machinery for ultimate removal and DNA demethylation, PARP (a component of base excision repair), was suggested as a potential target in the context of vitamin C treatment (Figure 5A). In vitro, vitamin C appears to sensitize AML cells to PARP inhibition,149 although additional preclinical studies are required to strengthen a hypothesis of synergy and antileukemic activity.

Vitamin C transport

Cellular uptake of vitamin C is facilitated primarily by sodium vitamin C cotransporters (SVCTs) and GLUTs. SVCTs transport the reduced form of vitamin C (ascorbate), whereas GLUTs (GLUT1 and GLUT3) transport the oxidized form of vitamin C (dehydroascorbate).151 SLC23A2 (also known as SVCT2) is expressed in most hematopoietic cells, but expression is comparatively higher in HSCs and multipotent progenitors.150,152 The expression of SLC23A2 in AML blasts is typically low, impairing vitamin C uptake and restoration of TET2 activity.153 Nevertheless, vitamin C–restorative therapies remain appealing. To this end, several recent case reports and studies have investigated a role for vitamin C therapy in the treatment of AML and shown benefit.57-59 Further clinical evaluation is ongoing (#NCT03397173). Ideally, genetic and transcriptional context (eg, TET2 mutation status or SLC23A2 expression) will help to stratify response. Meanwhile, additional studies have identified TET-independent effects of vitamin C treatment in AML cells, such as the suppression of HIF1α and antiapoptotic BCL-2 family members (BCL2, BCL2L1, and MCL1).154

Vitamin B6

Vitamin B6 comprises 6 interconvertible 3-hydroxy-2-methylpyridine compounds. Mammals do not synthesize vitamin B6 de novo. They instead take up and convert dietary vitamin B6 into biologically active pyridoxal 5′- phosphate (PLP) using the vitamin B6 salvage pathway.155 PLP is a cofactor for a variety of reactions important for amino acid, nucleic acid, and FA metabolism. Our group recently showed that vitamin B6 metabolism is essential for AML maintenance and serves as a potential point of therapeutic intervention.60 We specifically demonstrated that pyridoxal kinase, which catalyzes PLP production, is required for the synthesis of key metabolites required for the proliferation of AML (Figure 5B). This AML dependency is mediated in part through the activity of PLP-dependent enzymes such as ornithine decarboxylase and aspartate aminotransferase. Importantly, pharmacologic disruption of PLP-dependent metabolism using pyridoxal kinase inhibitors such as isoniazid and 4′-O-methoxypyridoxine blocked AML proliferation.60

Retinoic acid

The active metabolite of vitamin A, retinoic acid plays a critical role in the pathophysiology and treatment of APL. This concept is long established and has been extensively reviewed,156-158 but to summarize, APL typically harbors the t(15;17)(q24.1;q21.2) cytogenetic abnormality that links the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene with the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARA) gene. The resultant PML-RARA fusion protein aberrantly binds DNA at retinoic acid–responsive elements, leading to altered gene expression, inhibition of RARA signaling in a dominant-negative fashion, and myeloid differentiation arrest. Given this pathogenesis, a chemotherapy-sparing regimen of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) plus arsenic trioxide, has become the standard of care for low-risk APL, yielding near-universal CRs and >95% event-free survival rates.61 Mechanistically, pharmacologic levels of ATRA overcome the differentiation arrest through transcriptional derepression and degradation of PML-RARA, the latter of which is facilitated by arsenic trioxide.159 To date, APL treatment stands as the quintessential metabolism-directed differentiation therapy. However, more recent studies suggest a potential role for retinoic acid in promoting the differentiation of non-APL disease (eg, NPM1-mutated AML), and clinical trials of ATRA or tamibarotene (a RARA agonist) plus HMAs have shown promise.160-163

Resistance mechanisms to the current treatment

Just as metabolic pathways have been implicated in the pathophysiology of AML, they have similarly been implicated in resistance to existing therapies.

Cytarabine resistance

As noted above, cytarabine is used extensively in AML, serving as effective monotherapy as well as the backbone of combinatorial chemotherapeutic regimens. Mechanistically, cytarabine is transported across the cell membrane by hENT1, encoded by SLC29A1. Loss-of-function mutations in hENT1 result in cytarabine resistance, requiring patients to receive higher doses of cytarabine at the time of relapse to counteract this effect, albeit, with the cost of increased toxicity.164 Deoxycytidine kinase (DCK), a rate-limiting enzyme for the activation of cytarabine, catalyzes the phosphorylation of cytarabine to cytarabine monophosphate, which is ultimately converted to the bioactive molecule, cytarabine triphosphate (Figure 3B). In AML cells rendered cytarabine resistant by exposure to increasing concentrations of the drug, DCK is downregulated, presumably resulting in a diminished antileukemic effect.165 Another enzyme, cytidine deaminase (CDA) inhibits cytarabine through its irreversible deamination to the inactive metabolite, uracil arabinoside. CDA overexpression is suggested as a possible mechanism for cytarabine resistance in patients with AML, whereby lower expression of CDA is associated with longer durations of remission.166,167 The above mechanisms; loss-of-function mutations in hENT1, reduced expression of DCK, and overexpression of CDA; have been shown to confer resistance to cytarabine and other nucleoside analogs in AML. Hence, strategies to bypass antimetabolite resistance are under development.

Venetoclax resistance

Multiple studies are now examining mechanisms that predict response and/or resistance to venetoclax plus HMA. Recently, it was shown that monocytic AML is more resistant to venetoclax-based therapy, downregulating BCL-2 and depending instead on MCL-1 for OXPHOS and cell survival.168 Using CRISPR-based screening, Sharon et al showed that inactivation of genes encoding regulators of mitochondrial translation could overcome venetoclax resistance.62 Accordingly, inhibition of mitochondrial translation using antibiotics (eg, tedizolid or doxycycline) was effective at restoring venetoclax sensitivity in resistant AML cells, and a triplet of tedizolid plus venetoclax plus azacitidine was more efficacious in PDX models than venetoclax plus azacitidine alone.62 Other recent studies demonstrated that ibrutinib (a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor) or cobimtinib (a MEK inhibitor) may enhance the activity of venetoclax in AML, although the precise mechanisms underlying these combinatorial effects require additional elucidation.63,64

Future perspectives

Over decades, many studies have investigated the role of metabolism in AML, culminating in recent successes. However, existing therapies are limited, reflecting difficulties in achieving efficacy while limiting toxicity. To overcome these challenges, the identification of metabolic perturbations specific to the heterogenous underlying genetic drivers and mutational configurations in AML remains essential. We have much to understand regarding the contribution of abnormal metabolism to the initiation, growth, and progression of leukemia for different subtypes of AML. Many metabolic pathways are shared by normal tissues. It is therefore imperative that we characterize the sensitivities of normal tissues, leukemic cells, and LSC compartments to metabolic perturbations in order to identify actionable therapeutic windows. Continued drug discovery and testing will be advanced by improving the in vitro process, generating relevant leukemic mouse models including PDXs, using combinatorial strategies, and selecting appropriate patient populations for clinical trials. The preclinical and clinical studies described above lay the groundwork for, and advance, what will hopefully be a growing arsenal of metabolism-based therapeutics for the betterment of human life in the near future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the CSHL President’s Council, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant P30 CA045508), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant U01 HL127522), National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant R01CA276938), Northwell Cancer Translational Research Award, Edward P. Evans Foundation MDS Young Investigator Award, and CDMRP Bone Marrow Failure Research Program Idea Development Award (L.Z.); and an American Society of Hematology Scholar Award and a grant from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (grant K08CA259453-01A1) (S.E.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: All authors wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lingbo Zhang, National Cancer Institute–Designated Cancer Center, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724; e-mail: lbzhang@cshl.edu.

References

Author notes

∗S.K.K. and S.E.M. contributed equally to this study.

![Vitamin metabolism in AML and relevant therapeutic strategies. (A) Regulation of TET enzymes by vitamin C (ascorbate). Schematic representation demonstrating the ascorbate-dependent regulation of the TET enzymes by ascorbate, as well as downstream epigenetic effects in HSCs (multipotent progenitors [MPPs]) and cancer stem cells. (B) Regulation of vitamin B6 (pyridoxal) in AML. Schematic representation of pyridoxal uptake and downstream utilization in AML cells, including a central role for PLP and downstream effector enzymes, ODC1 and GOT2 in leukemic proliferation. Enzymes and inhibitory compounds with demonstrated relevance to AML pathophysiology are highlighted in blue, and red, respectively. BER, base exclusion repair; 5CaC, 5-carboxylcytosine; 5fC, 5-formyl cytosine; DHA, dehydroascorbate; GOT2, glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 2; 5mC, 5-methylcytosine; 5hmC, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine; ODC1, ornithine decarboxylase.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/141/10/10.1182_blood.2022018092/3/m_blood_bld-2022-018092-c-gr5.jpeg?Expires=1762710987&Signature=SVm~dSZoHb~NSU6mByeggdsyxBwBVlFprnCNZ9p5B-oBnN~rDNKwsX1d4Nt51HHI9aNtstoE6nn5LbxFr42DYvakqS5P3iAFqVTHxUW3mlWDOsJknGpvbRCCDNFByTY6nLRLwl21ijgtPuATkOXEJPuGOTuOtMAH8AWTlCU1HJpiRLeMAuOOjGhFRQhkIh7kH3H1n2gMbRYqgYx8c3on2SB7B5e4pppxVodEjTQOgB8UeBSZV0Q31GTBy6BQf9wp5fECgIZMshc261tmwC2tnx-CzlwKphYzKJ21bSJYtX1wknaEJvUzUB8MX5epinAwb9vhcEIAxV0laMXLMTcRZw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal