Abstract

Background: Increasing evidence suggests that adult cancer genes (ACGs) contribute substantially to the development of several malignancies in childhood, although with reduced penetrance. The association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 with breast and ovarian cancer is sufficiently described, as well as the presence of heterozygous mutations in one of the mismatch repair genes (MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, PMS2) in hereditary colon carcinoma. Moreover, there is a plethora of genes, mainly regulating DNA repair mechanisms and cell cycle arrest as BRIP1, CHEK2, ATM, PALB2, HOXB13, RAD51C, RAD51D, which predispose to a variety of adult type cancers. The recurrent presence of pathogenic variants in one of the ACGs is observed in several pediatric cancer cohorts and gaining recognition in the field of pediatric cancer susceptibility. However, the incidence and impact of ACGs in childhood cancer and especially in pediatric hematological malignancies is not fully explored yet.

Aims: Our aim is to understand the frequency and the impact of germline variants in adult cancer predisposition genes in the etiology of hematological malignancies in children.

Methods: We analyzed parent-child whole exome sequencing (WES) data of 162 children (<18yrs) with hematological malignancies (N=117 leukemia, N=43 lymphoma, N=2 myelodysplastic syndrome) for the presence of pathogenic variants in adult onset cancer predisposition genes. For part of the detected variants, we performed further functional analysis to investigate the effect of the alteration on protein function.

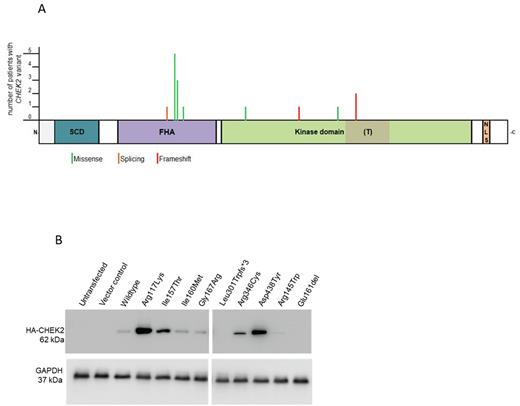

Results: We diagnosed a classical cancer predisposition syndrome associated with the respective hematological malignancy in 5/162 patients (3%): Li-Fraumeni (N=1), Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) (N=1), Nijmegen-Breakage syndrome (NBS) (N=1) and Noonan syndrome (N=2). Additionally we identified in 19/162 patients a pathogenic / likely pathogenic variant (P/LP) in one of the ACGs, including BRIP1, CHEK2, HOXB13, BRCA1, MSH2 and STK11. Strikingly, we observed a high frequency of CHEK2 germline variants in our cohort (15/162) (Figure 1A). The majority of those patients had a leukemia (N=11 BCP-ALL, N=1 T-ALL, N=1 CML) and two patients were diagnosed with a Hodgkin lymphoma. Interestingly, eight different CHEK2 variants including three truncating variants were detected in our cohort. Three variants were recurrent (p.Ile157Thr N=5, p.Ile160Met N=3, p.Thr367Metfs*15 N=2). According to the classification of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics 7/8 variants identified in 14 patients were predicted to be pathogenic or likely pathogenic. For two of these variants an impaired function had been already described in the literature. To test the functional consequences of the five remaining variants, we overexpressed these, in comparison to two control CHEK2 variants, in U2OS cells. Four out of seven variants (N=1 truncating, N=1 in-frame deletion, N=2 missense) led to loss of protein expression (Figure 1B) and loss of CHEK2-Thr68 phosphorylation upon irradiation induced DNA damage. Hence, according to the functional analysis, five out of fifteen patients carried a CHEK2 variant impairing its function. Interestingly, 4/5 patients with a pathogenic variant had a BCP-ALL and 1/5 had a BCR-ABL CML that rapidly progressed to lymphoid blast crisis while under imatinib therapy (400 mg/m2).

Conclusion/Summary: We identified heterozygous pathogenic variants in ACGs in the germline of 11.7% of children with hematological malignancies by WES-based screening of 162 cases. Strikingly 14/162 patients (8,6%) harbored a P/LP variant in the CHEK2 gene. Functional studies revealed that five patients carried a germline variant leading to loss of CHEK2 expression and/or loss of Thr68 phosphorylation upon irradiation. We conclude that impaired CHEK2 function may be an important germline-encoded host factor predisposing to the development of hematological malignancies in children.

Figure 1 (A): Schematic representation of the CHEK2 protein indicating the localization of the identified variants. The length of the bars correlates to the number of patients with the respective CHEK2 variant and the color of the bars to the variant type (green: missense, red: frameshift indels, orange: splicing). (B): Western blot analysis of HA-tagged CHEK2 protein variants ectopically expressed in U2OS cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal