Key Points

Cavernomas have stable clots with polyhedrocytes that result in cerebral hypoxia.

CCM lesions have a vascular heterogeneity with coagulant and anticoagulant regions.

Abstract

Cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) is a neurovascular disease that results in various neurological symptoms. Thrombi have been reported in surgically resected CCM patient biopsies, but the molecular signatures of these thrombi remain elusive. Here, we investigated the kinetics of thrombi formation in CCM and how thrombi affect the vasculature and contribute to cerebral hypoxia. We used RNA sequencing to investigate the transcriptome of mouse brain endothelial cells with an inducible endothelial-specific Ccm3 knock-out (Ccm3-iECKO). We found that Ccm3-deficient brain endothelial cells had a higher expression of genes related to the coagulation cascade and hypoxia when compared with wild-type brain endothelial cells. Immunofluorescent assays identified key molecular signatures of thrombi such as fibrin, von Willebrand factor, and activated platelets in Ccm3-iECKO mice and human CCM biopsies. Notably, we identified polyhedrocytes in Ccm3-iECKO mice and human CCM biopsies and report it for the first time. We also found that the parenchyma surrounding CCM lesions is hypoxic and that more thrombi correlate with higher levels of hypoxia. We created an in vitro model to study CCM pathology and found that human brain endothelial cells deficient for CCM3 expressed elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and had a redistribution of von Willebrand factor. With transcriptomics, comprehensive imaging, and an in vitro CCM preclinical model, this study provides experimental evidence that genes and proteins related to the coagulation cascade affect the brain vasculature and promote neurological side effects such as hypoxia in CCMs. This study supports the concept that antithrombotic therapy may be beneficial for patients with CCM.

Introduction

Cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) is a vascular disease that is characterized by mulberry-like lesions in the brain and spinal cord.1,2 CCM lesions (cavernomas) are leaky, prone to rupture, and cause side effects such as epileptic seizures, hemorrhagic strokes, and focal neurological deficits.1,2 CCM can be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner (prevalence of 1:10 000) due to an endothelial specific loss-of-function mutation in 1 of the 3 CCM genes: CCM1(KRIT1), CCM2(OSM), or CCM3(PDCD10).3 Recently, gain-of-function mutations in PIK3CA were also reported in patients with CCM.4 Cavernomas can also appear spontaneously (prevalence of 1:200) as single isolated lesions.1,3 To date, neurosurgery is the only treatment for patients with CCM, and location makes some lesions inoperable.5

Coagulation has not been fully investigated in cavernomas, but recently it has been considered in the etiology of CCM.1,6-9 Some studies showed that surgically resected lesions were surrounded by encapsulated thrombi and a thick basal membrane.1,6,9 However, these studies did not identify the clear molecular signatures of microthrombi in CCM. Recently we have shown that inflammation in CCM recruits neutrophils with neutrophil extracellular traps10 to cavernomas, which, together with coagulant factors, are known to contribute to immunothrombosis.11

The data presented in this study shows that the hemostatic system is dysregulated in CCM and that it results in cerebral hypoxia. We found increased levels of genes and proteins related to the coagulation cascade in Ccm3-deficient mice. We also identified polyhedrocytes (compressed polyhedral erythrocytes)12 in CCM for the first time and show that cavernomas have a vascular heterogeneity in regards to coagulation. We identified regions prone to thrombi (“hot” regions) and regions prone to hemorrhage (“cold” regions). Our study supports the concept that CCM lesions are dynamic and have both procoagulant and anticoagulant regions.

Methods

Genetically modified mice

Cdh5(PAC)-Cre-ERT2/Ccm3flox/flox(Ccm3-iECKO) mice were generated as previously described.13 In short, Cdh5(PAC)-Cre-ERT2/Ccm3flox/flox pups with a single Cre allele were injected intragastrically with 60 μg tamoxifen (T5648; Sigma-Aldrich) at postnatal day 1 (P1). Cdh5(PAC)-Cre-ERT2/Ccm3flox/flox Cre-negative pups, and in some experiments Cdh5(PAC)-Cre-ERT2/Ccm3flox/flox Cre-positive pups injected with corn oil, were used as wild-type controls.

Endothelial cell isolations

At P9, wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The cerebellums were dissected, minced, and dissociated with the gentleMACS Octo Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) following the instructions of the Adult Brain Dissociation kit (130-107-677; Miltenyi Biotec). CD45+ cells were removed from the homogenate with CD45 MicroBeads (30-052-301; Miltenyi Biotec), and endothelial cells were enriched with CD31 MicroBeads (30-097-418; Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Details regarding RNA extraction and library preparation can be found in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website.

RNAscope

At P8, wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of Avertin (Sigma #T48402, 0.4 mg/g) and perfused through the heart with Hanks buffered saline solution (Gibco). Brains were dissected, coronally embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, and snap frozen. Samples were sectioned with a cryostat (10 μm) and processed for RNAscope according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ACD Bio, RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit v2 Assay). Probes from ACD Bio were used to detect the genes encoding for claudin-5, tissue factor (TF), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor-a (VEGF-A) (Cldn5, F3, Serpine1, and Vegfa, respectively).

Immunofluorescence

At P6, P7, and P8 wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice were anesthetized as described above and perfused through the heart with 1% paraformaldehyde. The samples were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and then prepared for sectioning. Detailed methods for immunofluorescent experiments can be found in the supplemental Methods.

Human CCM brain biopsies

Brain biopsies from 6 patients with CCM were surgically obtained at the Department of Neurosurgery at Helsinki University Hospital in Finland. Paraffin-embedded biopsies from 3 patients with familial CCM were acquired from the Angioma Alliance DNA/Tissue Bank. In total, biopsies of 9 patients with CCM were analyzed in this study. Human brain biopsies from 2 patients with no known neurological symptoms were purchased from AMS Biotechnology Limited. Detailed methods for biopsy processing and staining can be found in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Transcriptome analysis identified genes related to the coagulation cascade and hypoxia in Ccm3-null mouse brain endothelial cells

To identify novel molecular mechanisms that contribute to CCM pathology, we analyzed the transcriptome of mouse brain endothelial cells (MBECs) isolated from wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (Figure 1A). We identified 1041 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between wild-type and Ccm3-null MBECs (supplemental Figure 1A); among them, 600 were upregulated and 441 were downregulated (Figure 1B). Using the MsigDB Hallmark Gene Sets collection, we found that several DEGs were related to coagulation and hypoxia: 87 upregulated DEGs; 34 downregulated DEGs (Figure 1B). We performed pathway enrichment using upregulated DEGs and found that blood coagulation, hemostasis, wound healing, and response to wounding were among the top overrepresented Gene Ontology (GO) terms in Ccm3-null MBECs (Figure 1C). Genes listed in those GO terms were related to thrombosis (F2rl1, Serpine1, F5, and Thbs1), anticoagulation (Anxa5 and Thbd), and hypoxia (Vegfa and Hif1a) (Figure 1D and supplemental Figure 1B). In addition, a gene set enrichment analysis confirmed that genes involved in coagulation and hypoxia (normalized enrichment score [NES] > 2 and false discovery rate [FDR] < 5%) were significantly higher in Ccm3-null MBECs than in wild-type MBECs (Figure 1E).

Transcriptome analysis reveals coagulation and hypoxia in CCM pathogenesis. (A) Diagram illustrating the study design of the transcriptome analysis of cerebellar brain endothelial cells (EC) isolated from wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (n = 3 mice per group). (B) Bar plot showing the number of significantly DEGs between wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice; 600 genes were upregulated and 441 were downregulated in Ccm3-iECKO mice. Importantly, 87 upregulated genes and 34 downregulated genes were related to coagulation and hypoxia. (C) Bar plot of a Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the upregulated genes in Ccm3-iECKO mice showing the top 20 overrepresented GO terms ranked by the number of DEGs in each group. GO terms related to coagulation are highlighted in red and marked with a star. (D) Heat map showing the expression levels (z score of regularized log [rlog]-transformed counts) of significantly upregulated DEGs (adjusted P value < .05 & |log2foldchange|>.5; blue: low; red: high) in Ccm3-iECKO mice. The first annotation after the biological replicates (wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice 1-3) indicates the differential expression in log2-fold change (Log2FC, red: high; white: low). The second to fifth annotations indicate the DEGs associated with enriched GO terms from the overrepresentation analysis in panel C. The genes labeled in red are described in this study. (E) Gene set enrichment analysis with hallmark enrichment plots demonstrating that genes related to coagulation and hypoxia were more expressed in endothelial cells isolated from Ccm3-deficient mice than endothelial cells of wild-type mice (NES > 2 and FDR < 5%). (F) Heat map showing the log-fold change of selected genes (related to coagulation and hypoxia, selected from panel D) in different endothelial subtypes of Ccm3-iECKO mice. On the right side the number of DEGs related to coagulation and hypoxia are listed for each endothelial subtype (upregulated in red, downregulated in blue; adjusted P value < .05). Only genes that were significantly differentially expressed between Ccm3-iECKO and wild-type mice in at least 1 endothelial cell subtype are shown. The identify of each endothelial cell cluster (C) is as follows: Cap, capillary (C0); Tip, tip cells (C1, C6); Mit Ven, mitotic/venous capillary (C2, C7); Art Cap, arterial capillary (C3, C5); Ven Cap, venous capillary (C4); Art, arterial (C8); Ven, venous/venous capillary (C9); Cap Tip, capillary/tip cells (C12, C14). Extr., extrinsic; neg., negative; path., pathway; pos., positive; reg., regulation; sig., signaling; rcp., receptors.

Transcriptome analysis reveals coagulation and hypoxia in CCM pathogenesis. (A) Diagram illustrating the study design of the transcriptome analysis of cerebellar brain endothelial cells (EC) isolated from wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (n = 3 mice per group). (B) Bar plot showing the number of significantly DEGs between wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice; 600 genes were upregulated and 441 were downregulated in Ccm3-iECKO mice. Importantly, 87 upregulated genes and 34 downregulated genes were related to coagulation and hypoxia. (C) Bar plot of a Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the upregulated genes in Ccm3-iECKO mice showing the top 20 overrepresented GO terms ranked by the number of DEGs in each group. GO terms related to coagulation are highlighted in red and marked with a star. (D) Heat map showing the expression levels (z score of regularized log [rlog]-transformed counts) of significantly upregulated DEGs (adjusted P value < .05 & |log2foldchange|>.5; blue: low; red: high) in Ccm3-iECKO mice. The first annotation after the biological replicates (wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice 1-3) indicates the differential expression in log2-fold change (Log2FC, red: high; white: low). The second to fifth annotations indicate the DEGs associated with enriched GO terms from the overrepresentation analysis in panel C. The genes labeled in red are described in this study. (E) Gene set enrichment analysis with hallmark enrichment plots demonstrating that genes related to coagulation and hypoxia were more expressed in endothelial cells isolated from Ccm3-deficient mice than endothelial cells of wild-type mice (NES > 2 and FDR < 5%). (F) Heat map showing the log-fold change of selected genes (related to coagulation and hypoxia, selected from panel D) in different endothelial subtypes of Ccm3-iECKO mice. On the right side the number of DEGs related to coagulation and hypoxia are listed for each endothelial subtype (upregulated in red, downregulated in blue; adjusted P value < .05). Only genes that were significantly differentially expressed between Ccm3-iECKO and wild-type mice in at least 1 endothelial cell subtype are shown. The identify of each endothelial cell cluster (C) is as follows: Cap, capillary (C0); Tip, tip cells (C1, C6); Mit Ven, mitotic/venous capillary (C2, C7); Art Cap, arterial capillary (C3, C5); Ven Cap, venous capillary (C4); Art, arterial (C8); Ven, venous/venous capillary (C9); Cap Tip, capillary/tip cells (C12, C14). Extr., extrinsic; neg., negative; path., pathway; pos., positive; reg., regulation; sig., signaling; rcp., receptors.

Because the RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data showed that genes related to the coagulation cascade and hypoxia were highly expressed in Ccm3-null MBECs, we analyzed our previously published single-cell RNA-seq data set to investigate how those genes were expressed in different endothelial subtypes.14 Coagulation and hypoxia-related genes were mostly present in the venous/venous capillary endothelial cells (cluster 9, 26 upregulated and 7 downregulated genes) and in the tip endothelial cell cluster (cluster 6, 25 upregulated and 3 downregulated genes) (Figure 1F). The remaining endothelial cell subtypes showed 6 to 19 upregulated and 1 to 4 downregulated coagulant and hypoxic genes (Figure 1F). Most of the DEGs in the single-cell RNA-seq data set associated with coagulation and hypoxia were also upregulated in the Ccm3-null venous/venous capillary MBECs (Figure 1F). However, none of those coagulation- and hypoxia-related genes appeared in the arterial endothelial cluster (cluster 8) (Figure 1F).

To investigate the spatial expression of the genes identified in the RNA-seq data set, we analyzed our previously published spatial transcriptomics data (P8 wild-type and acute Ccm3-iECKO mice).14 The expression of F3 and Vegfa was higher in Ccm3-iECKO mice than in wild-type mice (Figure 2A,C,E; quantifications in Figure 2B,D, and F, respectively; lesions outlined in Figure 2G). We then investigated the spatial expression of F3, Serpine1, and Vegfa with RNAscope to visualize them at a higher resolution (Figure 2H,J,K, and L, respectively). We found that all 3 genes were higher in the Ccm3-iECKO mice (Figure 2I,K,M) compared with wild-type mice, although F3 and Vegfa were not statistically significant. Of interest, F3 and Vegfa appeared in the granular and molecular layers of the cerebellum (asterisks) and Serpine1 was expressed by endothelial cells lining the lesions (arrows).

CCM pathology promotes the expression of genes and proteins related to the coagulation cascade and hypoxia in vivo. (A) Visium spatial transcriptomics illustrating the expression of F3 in wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO P8 cerebellum sections. (B) Quantification of F3 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice. (C) Visium spatial transcriptomics illustrating the expression of Serpine1 in wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO cerebellums. (D) Quantification of Serpine1 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice. (E) Visium spatial transcriptomics illustrating the expression of Vegfa in wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO cerebellums. (F) Quantification of Vegfa in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice. (G) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained Ccm3-iECKO P8 cerebellum sections with lesions outlined in green. (H) RNAscope images of representative wild-type (right panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (left panel) cerebellum sections; a region is highlighted with a white box and magnified to the right. Lesions are outlined in dotted white lines and regions of interest are marked with a white asterisk; 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole(DAPI) (blue), Cldn5 (green), F3 (magenta). (I) Quantification of F3 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0635). (J) RNAscope images of representative wild-type (right panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (left panel) cerebellum sections. Lesions are outlined in dotted white lines; DAPI (blue), Cldn5 (green), Serpine1 (magenta). (K) Quantification of Serpine1+Cldn5+ endothelial cells in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0159). (L) RNAscope images of representative wild-type (right panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (left panel) cerebellum sections; a region is highlighted with a white box and magnified to the right. Lesions are outlined in dotted white lines; DAPI (blue), Cldn5 (green), Vegfa (magenta). (M) Quantification of Vegfa in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0635). (N) Primary human brain endothelial cells (HBECs) transduced with shRNA (scramble or CCM3) blotted and quantified (O) CCM3 (P = .0035), (P) TF (P = .3650), (Q) VEGF-A (P = .8346), and (R) PAI-1 (P = .0178). In the graphs N-R, n = 3 independent experiments. In graphs B, D, F, I, K, and M each data point represents 1 biological replicate (n = 2-8 mice per group), the bar indicates the mean of each group, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. For the RNAscope graphs, a Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare wild-type mice with Ccm3-iECKO mice. For the western blot quantifications, a t-test was used to compare shScramble with shCCM3 cells. The corresponding P values are indicated on each graph. L, lesion.

CCM pathology promotes the expression of genes and proteins related to the coagulation cascade and hypoxia in vivo. (A) Visium spatial transcriptomics illustrating the expression of F3 in wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO P8 cerebellum sections. (B) Quantification of F3 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice. (C) Visium spatial transcriptomics illustrating the expression of Serpine1 in wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO cerebellums. (D) Quantification of Serpine1 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice. (E) Visium spatial transcriptomics illustrating the expression of Vegfa in wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO cerebellums. (F) Quantification of Vegfa in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice. (G) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained Ccm3-iECKO P8 cerebellum sections with lesions outlined in green. (H) RNAscope images of representative wild-type (right panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (left panel) cerebellum sections; a region is highlighted with a white box and magnified to the right. Lesions are outlined in dotted white lines and regions of interest are marked with a white asterisk; 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole(DAPI) (blue), Cldn5 (green), F3 (magenta). (I) Quantification of F3 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0635). (J) RNAscope images of representative wild-type (right panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (left panel) cerebellum sections. Lesions are outlined in dotted white lines; DAPI (blue), Cldn5 (green), Serpine1 (magenta). (K) Quantification of Serpine1+Cldn5+ endothelial cells in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0159). (L) RNAscope images of representative wild-type (right panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (left panel) cerebellum sections; a region is highlighted with a white box and magnified to the right. Lesions are outlined in dotted white lines; DAPI (blue), Cldn5 (green), Vegfa (magenta). (M) Quantification of Vegfa in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0635). (N) Primary human brain endothelial cells (HBECs) transduced with shRNA (scramble or CCM3) blotted and quantified (O) CCM3 (P = .0035), (P) TF (P = .3650), (Q) VEGF-A (P = .8346), and (R) PAI-1 (P = .0178). In the graphs N-R, n = 3 independent experiments. In graphs B, D, F, I, K, and M each data point represents 1 biological replicate (n = 2-8 mice per group), the bar indicates the mean of each group, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. For the RNAscope graphs, a Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare wild-type mice with Ccm3-iECKO mice. For the western blot quantifications, a t-test was used to compare shScramble with shCCM3 cells. The corresponding P values are indicated on each graph. L, lesion.

The loss of CCM3 results in higher levels of PAI-1 in primary human brain endothelial cells

In this study, we developed a novel in vitro CCM model by silencing CCM3 in primary human brain endothelial cells (HBECs) with short hairpin RNA (shRNA). After silencing CCM3 (shCCM3, Figure 2N-O), we checked protein levels of TF, VEGF-A, and PAI-1. We found that TF and VEGF-A were unaffected between shScramble (control) and shCCM3 cells (Figure 2N,P, and Q, respectively). However, we found that PAI-1 was significantly higher in shCCM3 cells compared with shScramble cells (Figure 2N,R).

Ccm3-iECKO mice and human cavernomas have procoagulant regions

To investigate coagulation in CCM, we stained wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO cerebellum sections, at the peak of disease (P8),15 for signature coagulation mediators. TF is a potent initiator of the blood coagulation cascade, and, although not statistically significant, its expression was higher in Ccm3-iECKO mice compared with wild-type mice (supplemental Figures 2A-D and 3A-B). Similar to the RNAscope findings, TF appeared in the granular and molecular layers of the cerebellum. To investigate which cerebellar cells express TF, we checked the publicly available mouse cerebellar single-nucleus RNA-seq data set generated by the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.16,17 We found that astrocytes, Bergman glial cells, and granule neurons expressed the most F3 in healthy adult mice (supplemental Figure 3C). We then stained wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mouse brains with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; to identify astrocytes) and TF. We found that GFAP colocalized with TF near cavernomas in Ccm3-iECKO mice (supplemental Figure 3D, arrowheads).

Fibrin clots were clearly present in Ccm3-iECKO mice and absent in wild-type mice (Figure 3A-B). Fibronectin was also higher in Ccm3-iECKO mice (Figure 3A,C) and colocalized with fibrin (Figure 3A, arrows). Furthermore, von Willebrand factor (VWF) was low in wild-type mice and high in Ccm3-iECKO mice (Figure 3D-E). VWF was expressed by the vasculature; however, it also aggregated in the lumen of the lesions (Figure 3D, asterisks). A kinetic analysis of fibrin, fibronectin, and VWF in P6, P7, and P8 Ccm3-iECKO mice showed a rapid increase of all 3 proteins from P6 to P8 (supplemental Figure 4A,B, and C, respectively).

CCM lesions are procoagulant in vivo. (A) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with fibrin-fibrinogen (green), fibronectin (red), and isolectin (magenta). Colocalization of fibrin-fibrinogen and fibronectin is highlighted with an arrow. (B) Quantification of fibrin-fibrinogen in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0556). (C) Quantification of fibronectin in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0079). (D) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green), VWF (red), and DAPI (blue). A magnified image is shown in the right panel and the asterisks highlight secreted VWF. (E) Quantification of VWF in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0159). (F) A tile scan of a sporadic CCM patient biopsy with multiple lesions. DAPI (blue) highlights the nuclei of cells, fibrin-fibrinogen (green) highlights leakage and clots and VWF (magenta) outlines the vasculature and fills clots. A selected region (dashed box) is shown to the right and it demonstrates a large clot filled fibrin (green) and VWF (magenta). Fibrin and VWF colocalize in the clot (merged panel on the top right). (G) Confluent HBECs (shScramble, left and shCCM3, right) stained for VWF (green) VE-cadherin (red), and DAPI (blue). High magnification (zoom) images on the right side of each condition. Arrows represent VWF strings. In all graphs, each data point represents 1 biological replicate (n = 4-8 mice per group), the bar indicates the mean of each group, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare wild-type mice with Ccm3-iECKO mice; the corresponding P values are indicated on each graph.

CCM lesions are procoagulant in vivo. (A) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with fibrin-fibrinogen (green), fibronectin (red), and isolectin (magenta). Colocalization of fibrin-fibrinogen and fibronectin is highlighted with an arrow. (B) Quantification of fibrin-fibrinogen in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0556). (C) Quantification of fibronectin in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0079). (D) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green), VWF (red), and DAPI (blue). A magnified image is shown in the right panel and the asterisks highlight secreted VWF. (E) Quantification of VWF in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0159). (F) A tile scan of a sporadic CCM patient biopsy with multiple lesions. DAPI (blue) highlights the nuclei of cells, fibrin-fibrinogen (green) highlights leakage and clots and VWF (magenta) outlines the vasculature and fills clots. A selected region (dashed box) is shown to the right and it demonstrates a large clot filled fibrin (green) and VWF (magenta). Fibrin and VWF colocalize in the clot (merged panel on the top right). (G) Confluent HBECs (shScramble, left and shCCM3, right) stained for VWF (green) VE-cadherin (red), and DAPI (blue). High magnification (zoom) images on the right side of each condition. Arrows represent VWF strings. In all graphs, each data point represents 1 biological replicate (n = 4-8 mice per group), the bar indicates the mean of each group, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare wild-type mice with Ccm3-iECKO mice; the corresponding P values are indicated on each graph.

To validate our preclinical data of coagulation in CCM, we analyzed 9 biopsies from patients with CCM. Patient demographics and clinical background can be found in Table 1. We stained 6 biopsies from patients with sporadic CCM with fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF (Table 1). We used fibrin-fibrinogen to identify procoagulant regions and VWF to identify the vasculature. We found that some patients had large fibrin clots (Figure 3F and supplemental Figure 5A), and 1 patient had fibrin-fibrinogen–positive regions but no obvious clots (supplemental Figure 5B, patient #3). Although VWF was used to mark the vasculature, VWF also colocalized with fibrin in the lumen of the lesions (Figure 3F, asterisks). This suggests that VWF is secreted (by either activated endothelial cells or platelets) and is promoting a procoagulant environment in cavernomas. Of importance, healthy human brain biopsies did not have clots and expressed basal levels of fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF (supplemental Figure 5C and Table 1). To understand if the absence of CCM3 affects the expression of VWF, we stained shScramble and shCCM3 HBECs for VWF. We found that VWF was expressed in Weibel-Palade bodies in both shScramble and shCCM3 HBECs; however, VWF clearly appeared as strings in the absence of CCM3 (Figure 3G, arrows).

Patient demographics and clinical background

| Patient . | Age . | Gender . | Location of biopsy . | CCM type . | No. of lesions . | Lesion size (mm) . | Inherited mutation . | Hemorrhage . | Other symptoms . | Stained with . | Evidence of clots . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | F | Pons | Sporadic | >1 | 15 × 15 | None | Yes | No | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 2 | 48 | F | Pons | Sporadic | 1 | 10 | None | Yes | No | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 3 | 55 | F | Frontal lobe | Sporadic | 1 | 15 | None | Yes | No | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes∗ |

| 4 | 31 | M | Other | Familial | >10 | 25 | CCM1 | Yes | L, S, U, V | Fraser-Lendrum | Yes |

| 5 | 18 | M | Left frontal lobe | Familial | 2-10 | 10 | CCM2 | Yes, twice | C, H, S, U, V, vertigo | Fraser-Lendrum | Yes |

| 6 | 51 | F | Right temporal lobe | Familial | 2-10† | 25 | CCM1 | Yes | D, H, S, T, lethargy, V, tinnitus | Fraser-Lendrum | Yes |

| 7 | 23 | F | Parietal lobe | Sporadic | 1 | 20 | None | Yes‡ | T | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 8 | 31 | M | Parieto-occipital lobe | Sporadic | 1 | 20 | None | Yes | S | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 9 | 66 | M | Temporal lobe | Sporadic | >1 | 25 | None | Yes | S | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 10 | 34 | M | Frontal cortex | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | No |

| 11 | 69 | M | Frontal cortex | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | No |

| Patient . | Age . | Gender . | Location of biopsy . | CCM type . | No. of lesions . | Lesion size (mm) . | Inherited mutation . | Hemorrhage . | Other symptoms . | Stained with . | Evidence of clots . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | F | Pons | Sporadic | >1 | 15 × 15 | None | Yes | No | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 2 | 48 | F | Pons | Sporadic | 1 | 10 | None | Yes | No | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 3 | 55 | F | Frontal lobe | Sporadic | 1 | 15 | None | Yes | No | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes∗ |

| 4 | 31 | M | Other | Familial | >10 | 25 | CCM1 | Yes | L, S, U, V | Fraser-Lendrum | Yes |

| 5 | 18 | M | Left frontal lobe | Familial | 2-10 | 10 | CCM2 | Yes, twice | C, H, S, U, V, vertigo | Fraser-Lendrum | Yes |

| 6 | 51 | F | Right temporal lobe | Familial | 2-10† | 25 | CCM1 | Yes | D, H, S, T, lethargy, V, tinnitus | Fraser-Lendrum | Yes |

| 7 | 23 | F | Parietal lobe | Sporadic | 1 | 20 | None | Yes‡ | T | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 8 | 31 | M | Parieto-occipital lobe | Sporadic | 1 | 20 | None | Yes | S | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 9 | 66 | M | Temporal lobe | Sporadic | >1 | 25 | None | Yes | S | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | Yes |

| 10 | 34 | M | Frontal cortex | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | No |

| 11 | 69 | M | Frontal cortex | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Fibrin-fibrinogen and VWF | No |

Patients 10 and 11 were used as control human brain samples. The criteria for clots were based on the presence of fibrin, polyhedrocytes, or platelets.

C, coordination problems; D, decreased sensation; H, headaches; L, limb weakness; NA, not applicable; S, seizures; T, tingling sensation in extremities; U, understanding and speaking problems; V, vision problems.

Fibrin-positive regions, but absence of large clots.

In brain and skin.

Microbleeding.

Ccm3-iECKO mice and human familial CCM biopsies have stable clots and polyhedrocytes

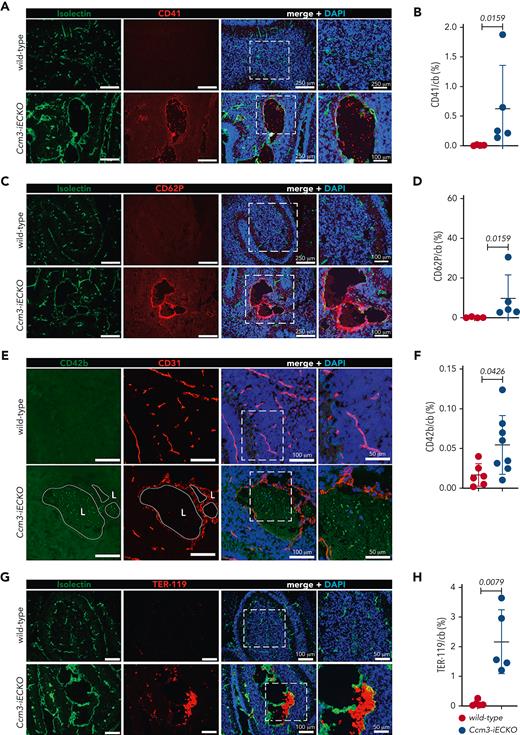

Upon vascular injury, TF and VWF mediate platelet adhesion and aggregation; therefore, we checked Ccm3-iECKO mice for CD41, a pan-marker of platelets and megakaryocytes. We found platelets in Ccm3-iECKO mice but not in wild-type mice (Figure 4A-B). A kinetic analysis of CD41 in P6-P8 Ccm3-iECKO mice showed an increase in platelets from P7 to P8 (supplemental Figure 4D). In addition, P-selectin/CD62P, a marker of activated endothelial cells and platelets, was higher in the absence of Ccm3 (Figure 4C-D) when compared with wild-type controls (Figure 4C). CD42b, another marker of activated platelets, was also higher in Ccm3-iECKO mice (Figure 4E-F, P = .0426) but undetected in wild-type mice (Figure 4E). To check for the presence of erythrocytes, which contribute to the formation of clots, we used TER-119 and found that erythrocytes remained low in Ccm3-iECKO mice from P6 to P7 but increased from P7 to P8 (supplemental Figure 4E). At P8 Ccm3-iECKO mice had more erythrocytes than wild-type controls (Figure 4G-H).

The endothelium of Ccm3-iECKO mice is activated and procoagulant. (A) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green), CD41 (red), and DAPI (blue). A magnified image is shown in the right panel. (B) Quantification of CD41 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0159). (C) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green), CD62P (red), and DAPI (blue). A magnified image is shown in the right panel. (D) Quantification of CD62P in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0159). (E) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with CD42b (green), CD31 (red), and DAPI (blue). A magnified image is shown in the right panel. (F) Quantification of CD42b area in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0426). (G) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green), TER-119 (red), and DAPI (blue). Merged image (left panel) shows TER-119-positive cells attached to the vessel wall in Ccm3-iECKO mice. (H) Quantification of TER-119 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0079). In all graphs, each data point represents 1 biological replicate (n = 4-8 mice per group), the bar indicates the mean of each group, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare wild-type mice with Ccm3-iECKO mice; the corresponding P values are indicated on each graph.

The endothelium of Ccm3-iECKO mice is activated and procoagulant. (A) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green), CD41 (red), and DAPI (blue). A magnified image is shown in the right panel. (B) Quantification of CD41 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0159). (C) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green), CD62P (red), and DAPI (blue). A magnified image is shown in the right panel. (D) Quantification of CD62P in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0159). (E) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with CD42b (green), CD31 (red), and DAPI (blue). A magnified image is shown in the right panel. (F) Quantification of CD42b area in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0426). (G) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green), TER-119 (red), and DAPI (blue). Merged image (left panel) shows TER-119-positive cells attached to the vessel wall in Ccm3-iECKO mice. (H) Quantification of TER-119 in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0079). In all graphs, each data point represents 1 biological replicate (n = 4-8 mice per group), the bar indicates the mean of each group, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare wild-type mice with Ccm3-iECKO mice; the corresponding P values are indicated on each graph.

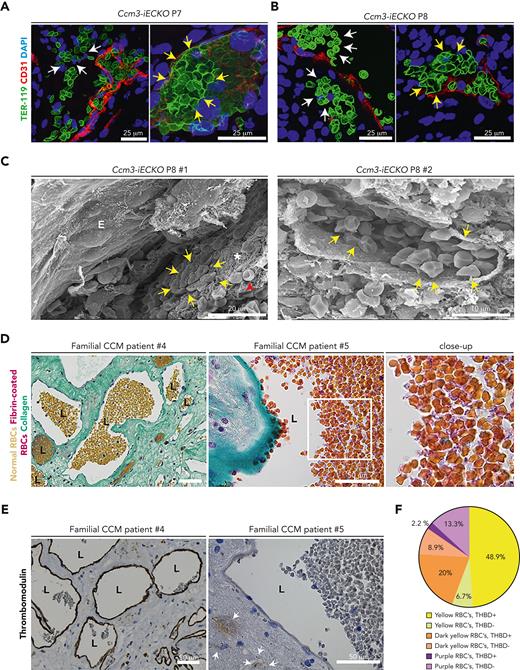

High-magnification images revealed microbleeds outside of the vasculature (Figure 5A, white arrows) and tight clusters of deformed erythrocytes in Ccm3-iECKO mice at P7 (Figure 5A, yellow arrows). Microbleeds and deformed erythrocytes were also seen at P8 (Figure 5B). Mouse cavernomas were analyzed via scanning electron microscopy. Fibrin clots were seen in some lesions (Figure 5C), and other lesions lacked clots (supplemental Figure 6A) but still showed activated platelet aggregates, fibrin threads, and biconcave erythrocytes (supplemental Figure 6B). Scanning electron microscopy images of lesions with clots revealed polyhedral erythrocytes (ie, polyhedrocytes) (Figure 5C, yellow arrows).

Vascular heterogeneity results in either microbleeds or polyhedrocytes at the vessel wall. (A) Confocal images of Ccm3-iECKO P7 (right) and (B) P8 (left) cerebellums illustrating microbleeds (white arrows) and polyhedral red blood cells (yellow arrows); DAPI (blue) TER-119 (green), and CD31 (red). (C) Scanning electron microscopy images of vessels in Ccm3-iECKO mice. In the right panel a clot near the vessel wall is seen with polyhedrocytes (yellow arrows), fibrin threads (asterisk), and regular red blood cells (red arrowhead). In the right panel, a vessel is seen with multiple polyhedrocytes. (D) Familial CCM patient biopsy stained for LENDRUM; normal red blood cells (yellow), fibrin-coated red blood cells (pink), and collagen IV (green). Different regions highlight the heterogeneity of red blood cells. In the left normal red blood cells are shown, and in the middle panel fibrin-coated red blood cells are highlighted. The region highlighted in a white box is magnified to the right. (E) Familial CCM patient biopsy stained for thrombomodulin. Patient #4 shows lesions with a high expression of thrombomodulin, and patient #5 shows a lesion with no thrombomodulin. White arrow shows hemosiderin, which is an indication of a previous hemorrhage. (F) Pie chart showing the quantification of the heterogeneous expression of thrombomodulin relative to red blood cell (RBC) composition. THBD, thrombomodulin; RBC, red blood cells.

Vascular heterogeneity results in either microbleeds or polyhedrocytes at the vessel wall. (A) Confocal images of Ccm3-iECKO P7 (right) and (B) P8 (left) cerebellums illustrating microbleeds (white arrows) and polyhedral red blood cells (yellow arrows); DAPI (blue) TER-119 (green), and CD31 (red). (C) Scanning electron microscopy images of vessels in Ccm3-iECKO mice. In the right panel a clot near the vessel wall is seen with polyhedrocytes (yellow arrows), fibrin threads (asterisk), and regular red blood cells (red arrowhead). In the right panel, a vessel is seen with multiple polyhedrocytes. (D) Familial CCM patient biopsy stained for LENDRUM; normal red blood cells (yellow), fibrin-coated red blood cells (pink), and collagen IV (green). Different regions highlight the heterogeneity of red blood cells. In the left normal red blood cells are shown, and in the middle panel fibrin-coated red blood cells are highlighted. The region highlighted in a white box is magnified to the right. (E) Familial CCM patient biopsy stained for thrombomodulin. Patient #4 shows lesions with a high expression of thrombomodulin, and patient #5 shows a lesion with no thrombomodulin. White arrow shows hemosiderin, which is an indication of a previous hemorrhage. (F) Pie chart showing the quantification of the heterogeneous expression of thrombomodulin relative to red blood cell (RBC) composition. THBD, thrombomodulin; RBC, red blood cells.

To investigate erythrocyte activation and clot stability in human CCM, familial human CCM brain sections were stained with Fraser-Lendrum stain. With this stain, normal erythrocytes appear yellow, collagen appears light green, fibrin-coated regions appear pink/purple, and activated erythrocytes appear dark yellow-orange. We found that some lesions had normal erythrocytes (Figure 5D, left panel) and some lesions had fibrin-coated polyhedral erythrocytes (Figure 5D, middle and left panel). Supplemental Figure 7A-C shows that this staining pattern appeared in multiple patients with CCM (supplemental Figure 7A-C, patients 4-6). The same CCM biopsies were stained for CD34 and thrombomodulin (supplemental Figure 7A-C, patients 4-6). The thrombomodulin stain also had a heterogeneous expression in all patients with CCM. Some lesions had a strong thrombomodulin expression and others a low expression (Figure 5E).

Furthermore, we investigated the relationship between activated erythrocytes and thrombomodulin. Matched regions of the material were scored for activated erythrocytes and the level of thrombomodulin (supplemental Figure 7D). In 48.9% of the scored lesions, the expression of thrombomodulin was high with normal erythrocytes (Figure 5F). In agreement, 13.3% of the scored lesions had a low expression of thrombomodulin and fibrin-coated, activated erythrocytes (Figure 5F).

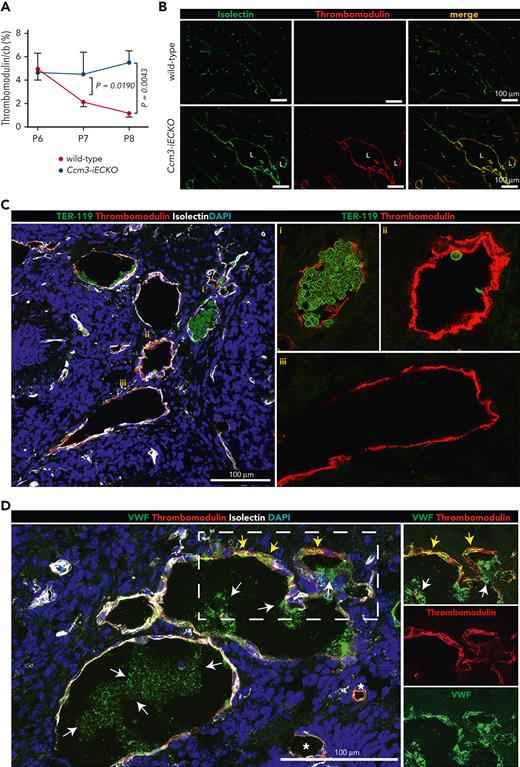

Vascular heterogeneity in the lesions of Ccm3-iECKO mice

We also investigated the expression of thrombomodulin in Ccm3-iECKO mice. We found a higher expression of thrombomodulin at P7 and P8 in Ccm3-iECKO mice when compared with wild-type controls (Figure 6A). Representative images of Ccm3-iECKO mice at P8 showed thrombomodulin upregulation in the vasculature (Figure 6B). Similar to our findings in human cavernomas, lesions of Ccm3-iECKO mice packed with polyhedrocytes had a lower expression of thrombomodulin (Figure 6Ci), and lesions largely void of erythrocytes expressed high levels of thrombomodulin (Figure 6Cii). Some lesions had an uneven expression of thrombomodulin (Figure 6Ciii). The expression of VWF was also heterogeneous (Figure 6D). Notably, thrombomodulin and VWF colocalized in some regions (Figure 6D, yellow arrows), and secreted VWF also appeared in the lumen of large lesions (Figure 6D, white arrows) but was absent in the lumen of small lesions (Figure 6D, left, asterisks). Furthermore, the anticoagulant gene/protein Anxa5/Annexin A5 was upregulated in Ccm3-iECKO mice (Figure 1D and supplemental Figure 8, respectively). To investigate the impact of flow on hemostasis in CCM pathology, we exposed HBECs to flow. The increased level of PAI-1 under static conditions (Figure 2N and supplemental Figure 9A) was partly reduced in cells exposed to flow (supplemental Figure 9A-B). Transcript levels of THBD and KLF2 increased with flow (supplemental Figure 9C-D).

Thrombomodulin is expressed in a heterogeneous manner in Ccm3-iECKO mice. (A) Kinetic expression of thrombomodulin at P6, P7, and P8 in the cerebellum (cb) shows that thrombomodulin expression decreased in wild-type mice (red line) but remained high in Ccm3-iEKO mice (blue line). Thrombomodulin was significantly higher in Ccm3-iEKO at P7 (P = .0190). and P8 (P = .0043) when compared with wild-type mice. (B) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green) and thrombomodulin (red). A merged image is shown in the right panel. (C) Images of the heterogeneous expression of erythrocytes (green) and thrombomodulin (red) show how (i) lesions filled with erythrocytes have a lower expression of thrombomodulin, whereas lesions that are hallowed (ii) and (iii) have a high expression of thrombomodulin. (D) Images showing the heterogeneous expression of VWF (green) and thrombomodulin (red) showing how some regions express high levels of vascular and extracellular VWF with thrombomodulin (dashed box, split channels to the right), and other vessels express low levels of VWF (asterisks). White arrows highlight secreted VWF, and yellow arrows highlight thrombomodulin/VWF colocalization. In panel A, the mean of n = 12 mice in each group are shown. Bars indicate the standard deviation in each group. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare wild-type mice with Ccm3-iECKO mice; the corresponding P values are indicated on each graph.

Thrombomodulin is expressed in a heterogeneous manner in Ccm3-iECKO mice. (A) Kinetic expression of thrombomodulin at P6, P7, and P8 in the cerebellum (cb) shows that thrombomodulin expression decreased in wild-type mice (red line) but remained high in Ccm3-iEKO mice (blue line). Thrombomodulin was significantly higher in Ccm3-iEKO at P7 (P = .0190). and P8 (P = .0043) when compared with wild-type mice. (B) Representative images of the cerebellum of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 mice stained with isolectin (green) and thrombomodulin (red). A merged image is shown in the right panel. (C) Images of the heterogeneous expression of erythrocytes (green) and thrombomodulin (red) show how (i) lesions filled with erythrocytes have a lower expression of thrombomodulin, whereas lesions that are hallowed (ii) and (iii) have a high expression of thrombomodulin. (D) Images showing the heterogeneous expression of VWF (green) and thrombomodulin (red) showing how some regions express high levels of vascular and extracellular VWF with thrombomodulin (dashed box, split channels to the right), and other vessels express low levels of VWF (asterisks). White arrows highlight secreted VWF, and yellow arrows highlight thrombomodulin/VWF colocalization. In panel A, the mean of n = 12 mice in each group are shown. Bars indicate the standard deviation in each group. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare wild-type mice with Ccm3-iECKO mice; the corresponding P values are indicated on each graph.

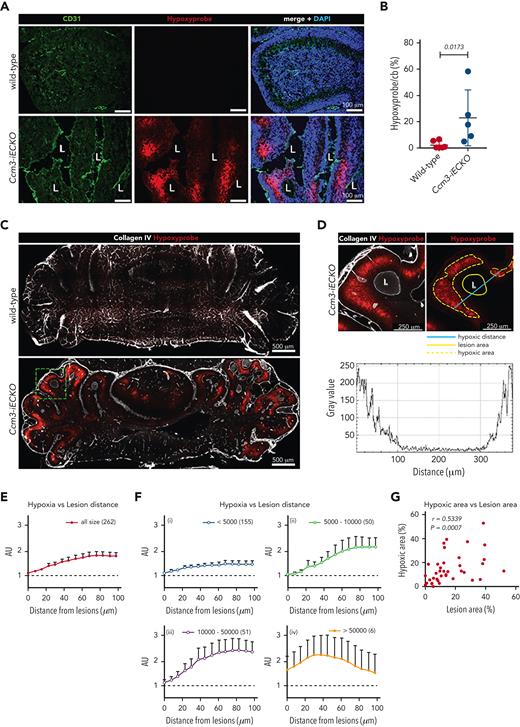

Ccm3-iECKO mice develop a hypoxic parenchyma after coagulation

Next, we investigated if coagulation affected brain oxygenation in Ccm3-iECKO mice. A linear increase in hypoxia was seen by hypoxyprobe staining from P6 to P8 (supplemental Figure 4F) with significantly more hypoxia in Ccm3-iECKO at P7 and P8 (supplemental Figure 4F). Notably, hypoxic regions consistently appeared outside of the lesions, in the parenchyma (Figure 7A). Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between fibrin-fibrinogen area and hypoxic area in Ccm3-iECKO mice (supplemental Figure 4G). There was also a positive correlation between the presence of erythrocytes and hypoxia (supplemental Figure 4H) and the presence of fibrin-fibrinogen and erythrocytes (supplemental Figure 4I). These findings support the hypothesis that coagulation triggers hypoxia in Ccm3-iECKO mice. Furthermore, lectin perfusions showed a reduced expression of injected lectin in the vasculature of Ccm3-iECKO mice compared with wild-type controls (supplemental Figure 9E-F).

CCM lesions are surrounded by hypoxia; more and larger lesions result in a hypoxic parenchyma. (A) Representative image of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 cerebellum sections: vessels are stained with CD31 (green), a marker of hypoxia (Hypoxyprobe, red), and DAPI (blue). Merged images (right panel) show that hypoxia appears in the periphery of the lesions. (B) Quantification of the hypoxic area in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0173). A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the 2 groups. Each point represents 1 biological replicate (n = 5-6 mice per group), the bar indicates the mean of each group, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. (C) Representative images of CLARITY-treated cerebellums of wild-type (upper) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower) mice stained with a marker of hypoxia (Hypoxyprobe, red), and collagen IV (white). (D) A magnified region of the dashed green square marked in panel C, illustrating how hypoxia and lesion distance were measured. The left panel shows hypoxia surrounding a lesion in 1 cerebellar lobe. Collagen IV is used to mark the vasculature. The right panel shows how lesion area, hypoxic area, and hypoxic distance were measured and the graph below shows the fluorescence intensity of hypoxia (gray value) after the hypoxic distance in micrometers was measured across the lesion. (E) Hypoxia intensity increases with distance from the lesions. Hypoxia intensity is shown as AU, which were determined by dividing the fluorescence intensity surrounding the lesions by the fluorescence intensity at the perimeter of the same lesions. Mean hypoxia intensity and lesion distance were determined for a total of 262 lesions from 3 Ccm3-iECKO mice. (F) The lesions were grouped by size (i-iv). The number of analyzed lesions in each group is indicated in parenthesis on the upper right corner of each graph. Data are shown as mean with 95% confidence intervals. (G) A total of 37 parts of the cerebellum (∼750 × 750 μm), such as in the lower image of panel C, were randomly selected from 5 sections of 3 Ccm3-iECKO mice and were evaluated for lesion size and hypoxic area. A correlation analysis was done between hypoxic area and lesion area. The Spearman correlation coefficient (r = 0.5339) and the corresponding P value (P = .0007) are indicated on the plot.

CCM lesions are surrounded by hypoxia; more and larger lesions result in a hypoxic parenchyma. (A) Representative image of wild-type (upper panel) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower panel) P8 cerebellum sections: vessels are stained with CD31 (green), a marker of hypoxia (Hypoxyprobe, red), and DAPI (blue). Merged images (right panel) show that hypoxia appears in the periphery of the lesions. (B) Quantification of the hypoxic area in the cerebellum (cb) of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (P = .0173). A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the 2 groups. Each point represents 1 biological replicate (n = 5-6 mice per group), the bar indicates the mean of each group, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. (C) Representative images of CLARITY-treated cerebellums of wild-type (upper) and Ccm3-iECKO (lower) mice stained with a marker of hypoxia (Hypoxyprobe, red), and collagen IV (white). (D) A magnified region of the dashed green square marked in panel C, illustrating how hypoxia and lesion distance were measured. The left panel shows hypoxia surrounding a lesion in 1 cerebellar lobe. Collagen IV is used to mark the vasculature. The right panel shows how lesion area, hypoxic area, and hypoxic distance were measured and the graph below shows the fluorescence intensity of hypoxia (gray value) after the hypoxic distance in micrometers was measured across the lesion. (E) Hypoxia intensity increases with distance from the lesions. Hypoxia intensity is shown as AU, which were determined by dividing the fluorescence intensity surrounding the lesions by the fluorescence intensity at the perimeter of the same lesions. Mean hypoxia intensity and lesion distance were determined for a total of 262 lesions from 3 Ccm3-iECKO mice. (F) The lesions were grouped by size (i-iv). The number of analyzed lesions in each group is indicated in parenthesis on the upper right corner of each graph. Data are shown as mean with 95% confidence intervals. (G) A total of 37 parts of the cerebellum (∼750 × 750 μm), such as in the lower image of panel C, were randomly selected from 5 sections of 3 Ccm3-iECKO mice and were evaluated for lesion size and hypoxic area. A correlation analysis was done between hypoxic area and lesion area. The Spearman correlation coefficient (r = 0.5339) and the corresponding P value (P = .0007) are indicated on the plot.

To investigate if larger lesions resulted in more hypoxia and how far hypoxia extended from lesions, we cleared the brains of wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (Figure 7C and supplemental Movies 1 and 2). Hypoxia only appeared near the lesions of Ccm3-iECKO mice (Figure 7C, lower panel, and Figure 7D). We selected 262 random lesions from 3 Ccm3-iECKO mice and measured their lesion area, the associated hypoxic area, and the furthest hypoxic distance from the lesion (Figure 7D, right panel). The graph in Figure 7D shows the fluorescence intensity of hypoxyprobe (gray value) along the indicated blue line drawn across the lumen of the lesion. The fluorescence intensity of hypoxyprobe (y-axis) and the lesion distance (x-axis) for the 262 lesions were plotted (Figure 7E). The lesions were grouped by size and we found that the hypoxic signal increased with lesion size and that the strongest hypoxic signal was 70 to 80 μm away from a lesion. The group with the smallest lesions (<5000 μm2) showed the weakest hypoxic signal (max mean arbitrary units [AU] = 1.49, Figure 7Fi) and lesions 5000 to 10 000 μm2 wide gave a maximum mean AU of 2.20 (Figure 7Fii). Lesions 10 000 to 50 000 μm2 wide showed the strongest hypoxic signal (max mean AU = 2.49, Figure 7Fiii), and the group with the largest lesions (>50 000 μm2) resulted in a different hypoxic pattern with a maximum hypoxyprobe signal of 2.0 AU at a 40-μm distance from the lesion (Figure 7Fiv). Lastly, we investigated whether more and/or larger lesions increased hypoxia by selecting 37 regions of the cerebellum (size = 750 μm × 750 μm) in the 3 Ccm3-iECKO mice. The lesion areas and their corresponding hypoxic areas were plotted and a moderate positive correlation was seen (Figure 7G).

Discussion

In this study we investigated the hemostatic system in CCM with preclinical CCM models and surgically resected human cavernomas. Our data show that coagulation is a phenomenon in CCM that it is followed by hypoxia. Microthrombi have been previously reported in surgically resected human CCM lesions1,6,9; however, in this study we define the kinetics of the thrombi formation, identify the molecular signatures of microthrombi in cavernomas, and show that they result in cerebral hypoxia.

TF is the major initiator of the coagulation cascade.18 We identified elevated levels of TF in Ccm3-iECKO mice and found that it was expressed by astrocytes surrounding the lesions. A recent study showed that proliferative astrocytes play a role in CCM pathology19 and, notably, astrocytes are the major producers of TF in the brain.20 Also, CCM-null endothelial cells undergo cellular stress such as dismantled junctions,21 and it is conceivable that the astrocytic end-feet, which are in direct contact with the endothelium,22 sense endothelial stress and in turn generate more TF.

When vascular integrity is disrupted, high levels of TF lead to the activation of thrombin, which cleaves soluble fibrinogen to insoluble fibrin monomers23 and promotes stable cross-linked fibrin clots with erythrocytes, activated platelets, and blood glycoproteins such as fibronectin and VWF.23 Here we identified fibrin clots that colocalized with erythrocytes, activated platelets, secreted VWF, and fibronectin in the lesion lumen of Ccm3-iECKO mice. Of interest, fibronectin has been described as an indicator of turbulent flow in atherogenesis.24 Furthermore, lectin perfusions showed a reduced lectin expression in lesion vasculature, which could indicate a dysregulated flow. Here we predict that large fibrin clots stabilized with fibronectin contribute to a turbulent flow that may create a backflow of blood into other regions of the fragile cavernoma and potentially lead to rupture, and thus cerebral hemorrhage.

The blood glycoprotein VWF is stored in Weibel-Palade bodies and is secreted by basal exocytosis or upon vascular activation.25 In normal conditions, CCM proteins restrain Weibel-Palade exocytosis.26 Here, we identified elevated levels of VWF in cavernomas and VWF strings in shCCM3 HBECs. VWF strings have been show to bind activated platelets and promote a prothrombotic environment.27 We also identified activated platelets with CD42b, a glycoprotein that forms a complex with factor IX and factor V and then binds to its receptor, VWF, to facilitate platelet adhesion to the endothelium.28 We also found that Ccm3-deficient MBECs had a higher yet heterogenous expression of Serpine1 and that shCCM3 HBECs expressed higher levels of the corresponding protein PAI-1, a serine protease linked to an increased risk of thrombosis in cancer patients.29 Because blood flow regulates hemostasis in endothelial cells, we investigated the effect of flow in shSramble and shCCM3 HBECs. PAI-1 was high in shCCM3 HBECs in static conditions, and it reduced upon exposure to flow. These results suggest that PAI-1 may be regulated by flow and low shear stress.

Notably, we identified polyhedrocytes in human and mouse cavernomas. When clots contract (to restore blood flow), erythrocytes undergo a phenotypic transformation and become polyhedrocytes.12 This polyhedral transformation allows erythrocytes to form a tight cluster at the site of injury and form a nearly impenetrable seal to prevent hemorrhage.12 Polyhedrocytes have been identified in diseases such as deep vein thrombosis,30 type 2 diabetes,31 and intracoronary thrombosis.32 Here, we report the presence of polyhedrocytes for the first time in CCM. Polyhedrocytes are unexpected in a disease that is mostly associated with bleeding. Cerebral hemorrhage is a hallmark of CCM, and it may result in severe neurological deficits33; however, polyhedrocytes are indicative of thrombi formation,34 suggesting that patients with CCM also experience coagulation. Indeed, histological investigation of human CCM biopsies showed evidence of fibrin clots, at different magnitudes, in all samples.

The activation of the coagulation cascade has previously been linked to hypoxia in mouse models of cerebral ischemia.35 Under hypoxic conditions, Vegfa, Hif1a, and several other genes related to angiogenesis, iron metabolism, glucose metabolism, cell proliferation, and survival are affected.36,37 Here we identified elevated levels of Vegfa in the cerebellar granular layer of Ccm3-iECKO mice. The cerebellar granular layer contains astrocytes,38 which have been shown to contribute to neurovascular dysfunction in CCM by secreting VEGF-A.19 Importantly, we found that the parenchyma surrounding cavernomas in Ccm3-iECKO mice is hypoxic. We hypothesize that coagulation in CCM drives hypoxia and increases the expression of VEGF-A in astrocytes. Notably, prolonged exposure to hypoxia may lead to neural cell loss and death, which may cause neuropathological conditions such as strokes,39 which many patients with CCM experience. Importantly, we also found that Hif1a was higher in Ccm3-deficient brain endothelial cells, suggesting that lesion endothelial cells sense the local hypoxia.

Anticoagulant proteins such as thrombomodulin, endothelial protein C receptor, and activated protein C have been shown to contribute to hemorrhage in cavernomas.8 In this study we found microthrombi in cavernomas; however, we also found elevated levels of the anticoagulant proteins Annexin IV and thrombomodulin. Interestingly we found a heterogeneous expression of thrombomodulin within the same lesion and between lesions. The expression of thrombomodulin was low in regions with polyhedrocytes and high in regions without polyhedrocytes. This suggests that cavernomas have a vascular heterogeneity and that they are prone to thrombi in some regions and prone to hemorrhage in other regions. We hypothesize that CCM lesions have “hot” and “cold” regions; “hot” regions are prothrombotic due to the presence of polyhedrocytes, which have been shown to prevent fibrinolysis,12 and “cold” regions are prone to hemorrhage due to their upregulation of anticoagulant proteins such as thrombomodulin and Annexin A5. These findings suggest that CCM lesions are dynamic, with anticoagulant and procoagulant regions that may be caused by different endothelial subtypes and a disturbed blood flow.

An ongoing debate in the CCM field is whether patients with CCM should receive anticoagulants. For a long time, anticoagulants were not prescribed to patients with CCM as they were thought to increase the risk of intracranial hemorrhage; however, a cohort study in 2013 revealed that antithrombotic pharmaceuticals did not promote hemorrhage in patients with CCM.40 In addition, a population-based cohort study showed that patients with CCM on antithrombotic pharmaceuticals actually had a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage compared with patients with CCM that were not on antithrombotic medications.41 Santos and colleagues also observed that patients on antithrombotic medication had fewer hemorrhagic events.42 All of these studies support our findings and show that understanding the molecular signatures of coagulation in CCM could give insights regarding suitable antithrombotic pharmaceuticals for patients with CCM.

In summary, this study shows that coagulation is an ongoing phenomenon in CCM and that it results in cerebral hypoxia. We identify polyhedrocytes for the first time in CCM and show that they are present in lesion thrombi. We further show that there is a coagulant vascular heterogeneity in CCM lesions as the hemostatic system is dysregulated. These findings contribute to the understanding of blood dynamics and endothelial cell diversity in CCM and support the concept that antithrombotic therapy may be beneficial for patients with CCM.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the BioVis Platform at Uppsala University for help with image scanning and analysis, the Angioma Alliance DNA/Tissue Bank (www.alliancetocure.org/dna-tissue-bank/) for the CCM patient biopsies, Svetlana Popova from the Research Development and Education Department at Uppsala University Hospital for preparing and staining the CCM patient biopsies, Ying Sun for preparing the GEO database, the SNP&SEQ sequencing facility at Uppsala, and R. H. Adams from the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine University in Münster for kindly donating the Cdh5(PAC)-Cre-ERT2 mouse line.

This study was supported by The Swedish Research Council (Contract No. 2013-9279 and 2021-01919), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (Contract No. 2015-0030), and the European Research Council (project EC-ERC-VEPC, Contract No. 74292).

Authorship

Contribution: M.A.G. designed the research, performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote and revised the manuscript; F.C.O., S.J., and A.C.Y.Y. performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, and revised the manuscript; F.O. and M.A. performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and revised the manuscript; L.L.C. analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and revised the manuscript; M.C., R.O.S., D.F., G.D., O.M., H.S., and A.W. performed research and revised the manuscript; C.R. and V.S. performed research; B.R.J., A.L., and M.N. acquired patient specimens and revised the manuscript; E.D. supervised the study; and P.U.M. supervised the study, designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Peetra U. Magnusson, Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, The Rudbeck Laboratory, Dag Hammarskjoldsv 20, 751 85 Uppsala, Sweden; e-mail: peetra.magnusson@igp.uu.se.

References

Author notes

The bulk RNA-seq dataset can be accessed from NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database through the accession number: GSE212018.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Transcriptome analysis reveals coagulation and hypoxia in CCM pathogenesis. (A) Diagram illustrating the study design of the transcriptome analysis of cerebellar brain endothelial cells (EC) isolated from wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice (n = 3 mice per group). (B) Bar plot showing the number of significantly DEGs between wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice; 600 genes were upregulated and 441 were downregulated in Ccm3-iECKO mice. Importantly, 87 upregulated genes and 34 downregulated genes were related to coagulation and hypoxia. (C) Bar plot of a Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the upregulated genes in Ccm3-iECKO mice showing the top 20 overrepresented GO terms ranked by the number of DEGs in each group. GO terms related to coagulation are highlighted in red and marked with a star. (D) Heat map showing the expression levels (z score of regularized log [rlog]-transformed counts) of significantly upregulated DEGs (adjusted P value < .05 & |log2foldchange|>.5; blue: low; red: high) in Ccm3-iECKO mice. The first annotation after the biological replicates (wild-type and Ccm3-iECKO mice 1-3) indicates the differential expression in log2-fold change (Log2FC, red: high; white: low). The second to fifth annotations indicate the DEGs associated with enriched GO terms from the overrepresentation analysis in panel C. The genes labeled in red are described in this study. (E) Gene set enrichment analysis with hallmark enrichment plots demonstrating that genes related to coagulation and hypoxia were more expressed in endothelial cells isolated from Ccm3-deficient mice than endothelial cells of wild-type mice (NES > 2 and FDR < 5%). (F) Heat map showing the log-fold change of selected genes (related to coagulation and hypoxia, selected from panel D) in different endothelial subtypes of Ccm3-iECKO mice. On the right side the number of DEGs related to coagulation and hypoxia are listed for each endothelial subtype (upregulated in red, downregulated in blue; adjusted P value < .05). Only genes that were significantly differentially expressed between Ccm3-iECKO and wild-type mice in at least 1 endothelial cell subtype are shown. The identify of each endothelial cell cluster (C) is as follows: Cap, capillary (C0); Tip, tip cells (C1, C6); Mit Ven, mitotic/venous capillary (C2, C7); Art Cap, arterial capillary (C3, C5); Ven Cap, venous capillary (C4); Art, arterial (C8); Ven, venous/venous capillary (C9); Cap Tip, capillary/tip cells (C12, C14). Extr., extrinsic; neg., negative; path., pathway; pos., positive; reg., regulation; sig., signaling; rcp., receptors.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/140/20/10.1182_blood.2021015350/5/m_blood_bld-2021-015350-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1767774558&Signature=MfC~3descFUFsV1tmvYlsqFqUYU5aczFIG49aIOeI9tCPohy3SICFTeWsl45m2mjwdlD0a-MdZ5bibnL4IS65e2MLz4SZ5JAjohpJQ2Ug8EDpjR5wNum5hEDpVdACF5aVOqoGV0qtx2DqnteJ4RZi3ZpGKM7zXX8ijHLz71dbqZEmAgFqBxiuZGSYGECTQp0bDU4iBlOpypeTFO12nMUyG-19MpAEt8lw8gb9G1IO~4~19gAlWjHHNFNa7c-MqYUo5j4sxxlECVUG4li2gonfeef3aK5ak8~SYv4EyBCTilq~tGNz2HkjWR-g68UcHlTTPX5ergg8YjyKQ6BxQDB-w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal