In this issue of Blood, Ghobadi and colleagues examine the role of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) in adults with Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) who achieve a complete molecular response within 90 days of starting treatment and conclude that allo-HCT does not improve overall survival compared with treatment with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) plus intensive chemotherapy.1 Ph+ ALL is an aggressive, frequently fatal leukemia that occurs mainly in adults. Potent inhibitors of the constitutively active ABL kinase have drastically improved outcomes for patients with Ph+ ALL and are a compulsory component of therapy. Historically, allo-HCT has also been a standard recommendation for all eligible patients in first complete remission (CR1).

In the preimatinib era, allo-HCT improved the rate of cure from dismal (<20%) to low (40%).2 The benefit of allo-HCT in CR1 was confirmed in the imatinib era.3,4 Subsequently, the potent second-generation (dasatinib, nilotinib) and then third-generation (ponatinib) TKIs have further improved outcomes, and cure is now achieved in the majority of transplant-eligible patients diagnosed with Ph+ ALL. As powerful TKIs move the survival needle upward, the necessary role of allo-HCT has become less certain for patients who respond rapidly and deeply to treatment with a TKI and intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy.5,6 A recent noncomparative, large case series of patients treated with a TKI plus the hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine sulfate, doxorubicin hydrochloride, and dexamethasone) regimen reported excellent outcomes in patients who achieved a BCR-ABL1 transcript level <0.01% by 3 months, even without allo-HCT.7

In this context, investigators from 5 transplant centers collaborated to report outcomes of a combined cohort of 230 adult patients diagnosed with Ph+ ALL over 2 decades (2001-2018) who had achieved a complete molecular response, defined as a BCR-ABL1 transcript level < 0.01% by quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay, within 90 days of treatment with TKI plus chemotherapy. Outcomes between those who did (n = 98) and did not (n = 132) receive allo-HCT in CR1 were compared. Most patients in the study were treated with hyper-CVAD (81%) plus dasatinib or ponatinib. Recipients of allo-HCT were younger, fitter, and less likely to have received ponatinib. Most transplants were myeloablative (82%), and approximately half (54%) included total body irradiation (TBI) conditioning.

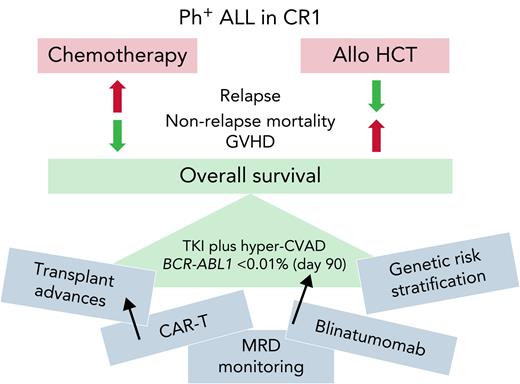

The primary study conclusion was that allo-HCT in CR1 did not improve overall and relapse-free survival in a cohort of intensively treated patients achieving BCR-ABL1 transcript level <0.01% within 90 days. In these patients, allo-HSCT was associated with less relapse but more nonrelapse mortality (and of course more graft-versus-host disease) so that overall survival was not statistically different between cohorts (see figure). In the absence of a randomized trial, this relatively large, retrospective study represents a noteworthy contribution to our knowledge. Importantly, the authors endeavored to address imbalances in patient and treatment characteristics between the allo and non-allo HCT cohorts with statistical adjustments, although the methods applied may not account for all factors biasing transplant referral.

Balancing the pros and cons of allo-HCT in CR1 for patients with Ph+ ALL achieving complete molecular remission after TKI plus chemotherapy.

Balancing the pros and cons of allo-HCT in CR1 for patients with Ph+ ALL achieving complete molecular remission after TKI plus chemotherapy.

Hematologists caring for adults with Ph+ ALL are hungry for data to guide practice. The findings of this study are significant, but the conclusions must be limited to comparable patients: those with newly diagnosed, de novo Ph+ ALL who achieve a deep remission (BCR-ABL1 transcript level <0.01%) within 90 days of treatment being managed with an intensive induction and consolidation chemotherapy regimen. This study does not address the role of allo-HCT in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in lymphoid blast crisis, therapy-related ALL (an increasingly recognized entity), or Ph+ ALL that responds more slowly to therapy. It also does not apply to those treated with a chemotherapy-free or chemotherapy-light approach. Indeed, a recent report from the ongoing GRAAPH 2014 study revealed inferior outcomes in patients who did not receive either intensive (cytarabine-based) consolidation or allo-HCT.8 Finally, this study does not address the need for allo-HCT in patients treated with novel chemotherapy-free regimens such TKI plus blinatumomab.9

Perhaps the biggest challenge of applying the findings of this study to current practice is the rapid expansion of knowledge and improvements in clinical practice in both Ph+ ALL and allo-HCT. Thus, the risk-benefit ratio of allo-HCT overall, and particularly within specific patient subgroups, is likely to continually evolve. Will patients with additional high-risk genetic features such as IKZF1 plus other copy number abnormalities be found to benefit from allo-HCT?10 Will use of measurable residual disease (MRD) assays more specific for the lymphoblastic disease compartment better identify patients needing therapeutic intensification with allo-HCT? Will advances in prevention and management of graft-versus-host disease, and development of non-TBI allo-HCT conditioning decrease toxicity and treatment-related mortality after allo-HCT? Will availability of more effective salvage therapies (TKI and non-TKI based) ensure that allo-HCT in CR2 can be reliably realized so that we do not need to “get it right the first time”? Will advances in chimeric antigen receptor therapy (CAR-T) make it the preferred and definitive salvage option in relapsed or refractory disease?

The management of Ph+ ALL is evolving at lightning speed, and it is imperative that prospective, randomized trials of transplant and nontransplant approaches be conducted to obtain the necessary high-quality data to rationally advance the field. In the meantime, the study by Ghobadi et al suggests that allo-HCT may be reasonably deferred in transplant-eligible patients who respond rapidly and deeply to a TKI plus intensive chemotherapy. Still, given the complexity of the disease and treatment landscape, as recommended by the authors, “early referral to a high-volume transplant center to evaluate transplant eligibility, identify potential allogeneic donors, and discuss the risks and benefits of allogeneic transplant as a therapeutic option remains an essential component of management in Ph+ ALL.” Until all the cards have been dealt, transplant colleagues: we still need you!

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal