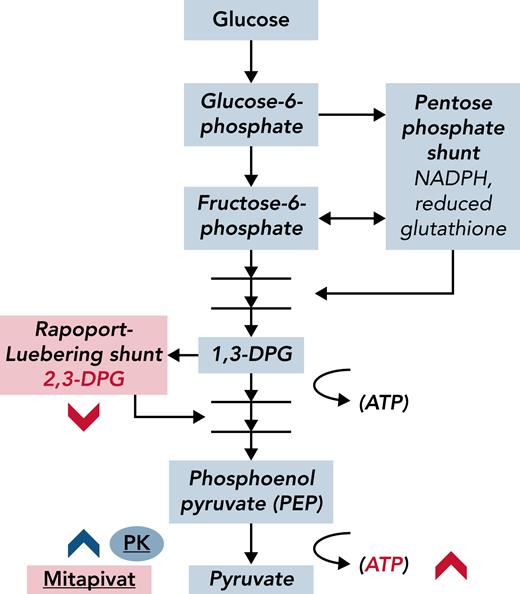

In this issue of Blood, Xu et al1 open the hood of the sickle hemoglobin (HbS)–containing red blood cells (RBCs) and cleverly soup up the carburetor; that is, they exploit endogenous metabolic pathways to improve RBC health in sickle cell disease (SCD) through activation of a distal enzyme in the glycolytic pathway, pyruvate kinase2 (PK; see figure). The goal is to increase the oxygen affinity of HbS by decreasing the concentration of the allosteric effector 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG).

In HbS, an increase in oxygen affinity inhibits polymer formation, and polymer formation is the proximate cause of much distress in patients with SCD, including hemolysis, anemia, inflammation, thrombophilia, pain, and organ damage. In a sense, PK activators endogenously recapitulate the actions of a novel small molecule, voxelotor (recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration), while also increasing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentrations in RBCs that contain HbS.

Sixteen adults with homozygous SCD successfully completed a 6- to 8-week trial of mitapivat, an oral activator of PK in RBCs. Slightly more than half of these patients (9 of 16) experienced an increase of ∼1 g/dL in total Hb, with suggestive decreases in markers of hemolysis and an acceptable safety profile.

PK deficiency results in damage to the RBC membrane and shortened RBC survival, hypersplenism, and anemia. From a biochemical standpoint, RBCs that are PK deficient and those that contain HbS both show decreased ATP, decreased oxygen affinity of Hb, increased 2,3-DPG, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), although they arise from distinct underlying mechanisms.3,4 In an earlier study of patients with PK deficiency, mitapivat improved total Hb in half the treated patients, without changes in levels of ATP or 2,3-DPG.5 In the Xu et al study of mitapivat in SCD, hemolysis and anemia improved, with measurably decreased 2,3-DPG and increased ATP. However, there was no change in the oxygen affinity of Hb, and the net impact of mitapivat on symptoms such as pain or fatigue in SCD was not evaluable in this uncontrolled study. Although it is likely that fatigue will decrease with an increase in Hb, and inflammatory damage will be less with a decrease in hemolysis, short-term improvements in pain are not ensured, and some pain was associated with the mitapivat treatment itself in the Xu et al study.

Using a PK activator in SCD is a striking leap of pathophysiological faith, and the potential of metabolic regulators to benefit people with SCD seems high. This is a truly innovative and exciting new avenue in providing care for patients with SCD. Nonetheless, the long-term clinical impact, associated pathophysiological effects, and related financial challenges of this class of drugs should be closely observed in the coming years.

Clinically, these are early days, and ongoing phase 2/3 clinical trials (NCT04624659, NCT04610866, and NCT04987489) will better describe the overall safety and functional impact of these medications in homozygous SCD. It will also be interesting to determine whether there are improvements in the health of RBCs and in clinical outcomes in sickle cell hemoglobin C (HbSC) and thalassemia (HbSβ+), orphans within an orphan disease in the United States, for which there are currently no well-validated disease-modifying therapies.

Adverse effects of mitapivat are manageable in patients with PK deficiency, as reported in a sizable and lengthy (6 months) trial5; however, hormonal perturbations and hypertriglyceridemia were reported, albeit at low levels. Of some concern, 2 patients with PK deficiency experienced accelerated hemolysis when treatment was abruptly halted. Unfortunately, in SCD we have seen that uninterrupted adherence can be problematic for patients who can get their medications only at specialty pharmacies, especially in a population that may experience limited resources, unstable insurance, and unreliable phone service. Prospectively acquired patient reported outcomes of fatigue or pain and/or physiological measures (eg, 6-Minute Walk Test) will give us a better understanding of the net effect of mitapivat and related medications on quality of life in people with SCD. The sustainability of improved hemolysis and the long-term impact on inflammation and organ damage will need to be monitored over time, because people with SCD have a wild-type PK enzyme, albeit with decreased activity.6

From a pathophysiological standpoint, it will be interesting to learn whether PK activation has a pan-cellular impact across the RBC lifespan. Single-cell analyses, such as those that examine RBC adhesion or deformability,7 may be more sensitive to this change than point-of-sickling analyses of the entire population (eg, Laser Optical Rotational Red Cell Analyzer [Lorrca] ektacytometry). In addition, the net effect of PK activation on oxidative stress is worth examining, because substrates in the antioxidant pentose pathway (see figure), and therefore ROS concentrations in RBCs, may be adversely affected by PK activation, despite evidence for overall improved health in RBCs (higher Hb, increased ATP) after treatment with mitapivat.

Glycolytic intermediaries are affected by the PK activator mitapivat in ways that improve hemolysis in SCD. Mature RBCs lack mitochondria; glycolysis is the anaerobic furnace for ATP production in these cells. Metabolic bypasses from the glycolytic pathway include the Rapoport-Luebering shunt, which generates 2,3-DPG, and the pentose phosphate shunt, which is a primary source of antioxidants (reduced glutathione) in RBCs. 2,3-DPG is a major allosteric effector of oxygen affinity in Hb; less 2,3-DPG results in slower oxygen release from Hb and delayed formation of deoxyhemoglobin, which is the major substrate for polymer formation in SCD. Activated PK (mitapivat, blue chevron) depletes 2,3-DPG, presumably through effective competition for 1,3-DPG. Theoretically, by decreasing 2,3-DPG and increasing oxygen affinity, less deoxyhemoglobin is produced. Xu et al have shown that in SCD, 2,3-DPG and ATP levels measurably changed (red chevrons) and that Hb levels increased after PK activation. NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen.

Glycolytic intermediaries are affected by the PK activator mitapivat in ways that improve hemolysis in SCD. Mature RBCs lack mitochondria; glycolysis is the anaerobic furnace for ATP production in these cells. Metabolic bypasses from the glycolytic pathway include the Rapoport-Luebering shunt, which generates 2,3-DPG, and the pentose phosphate shunt, which is a primary source of antioxidants (reduced glutathione) in RBCs. 2,3-DPG is a major allosteric effector of oxygen affinity in Hb; less 2,3-DPG results in slower oxygen release from Hb and delayed formation of deoxyhemoglobin, which is the major substrate for polymer formation in SCD. Activated PK (mitapivat, blue chevron) depletes 2,3-DPG, presumably through effective competition for 1,3-DPG. Theoretically, by decreasing 2,3-DPG and increasing oxygen affinity, less deoxyhemoglobin is produced. Xu et al have shown that in SCD, 2,3-DPG and ATP levels measurably changed (red chevrons) and that Hb levels increased after PK activation. NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen.

One cannot ignore the high cost of recently approved novel agents for SCD. Many people with SCD receive Medicaid, and Medicaid has struggled with high-cost treatments in the past, even when the treatments were curative.8 Many breakthrough therapeutic agents were developed only after significant public funding by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).9 It is possible to calculate the relative scientific contributions made to drugs discovered by using NIH funding, and it may be informative as we seek to appropriately acknowledge both private and public contributions to drug development, vis-à-vis appropriate cost for all novel agents in SCD. Equitable national and international integration of significant, life-improving, non-curative, and innovative therapies for SCD, such as PK activators, may prove to be, and should be, a priority in the coming decades.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.A.L. received research support from Global Blood Therapeutics (GBT), National Association of Sickle Cell Centers, and Bluebird Bio and is a member of the vaso-occlusion adjudication committee for the Hibiscus study from Forma.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal