In this issue of Blood, Armand and colleagues present results of the phase 2 CheckMate 140 study of programmed death-1 antibody nivolumab in recurrent follicular lymphoma. Although efficacy was limited, the authors did reveal important mechanistic insights into the immune response to nivolumab.1 Targeted inhibition of cellular immune checkpoints has proven to be a transformative therapeutic advance in both solid tumors and Hodgkin lymphoma. As a heterogeneous disease whose clinical behavior is heavily influenced by properties of the nonmalignant tumor microenvironment, follicular lymphoma is a logical setting in which to investigate immune modulation as treatment. The programmed cell death (PD) pathway, comprising the PD receptors (PD-1 and PD-2) and their ligands (PD-L1/L2), is activated by interactions between PD ligands and receptors, resulting in attenuation of downstream T-cell receptor signaling.2 This immune checkpoint is among several that play a critical role in modulating the innate antitumor immune response. Multiple tumors exploit this interaction to escape natural antitumor immunity.

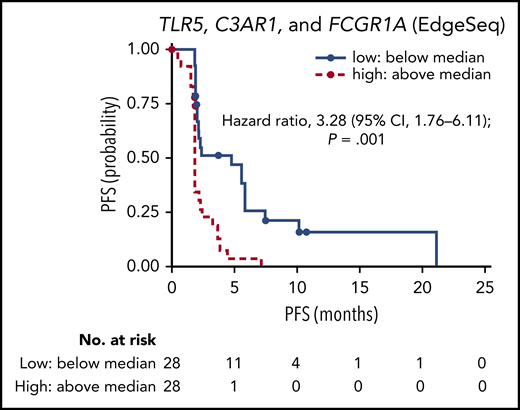

Outcomes with nivolumab in relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma based on gene expression signature. Progression-free survival (PFS) assessed by independent review committee by level of tumor-associated macrophage genes, TLR5, C3AR1, and FCGR1A. See Figure 4A in the article by Armand et al that begins on page 637.

Outcomes with nivolumab in relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma based on gene expression signature. Progression-free survival (PFS) assessed by independent review committee by level of tumor-associated macrophage genes, TLR5, C3AR1, and FCGR1A. See Figure 4A in the article by Armand et al that begins on page 637.

Although follicular lymphoma rarely expresses PD-L1/L2, nonmalignant tumor infiltrating T cells and macrophages in the tumor microenvironment do, and they also express PD-1. Pivotal studies have shown that, in general, elevated numbers of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment are associated with unfavorable outcomes, increased risk of disease progression, and death (immune response 2), whereas increased numbers of T cells correlate with a favorable prognosis (immune response 1).3 More recently, reduced intratumoral T cells have also been found to portend worse outcomes and increase the risk of early disease progression.4

It stands to reason that augmenting the antitumor immune response through checkpoint inhibition would be a promising approach in the treatment of follicular lymphoma. Moreover, elucidating the mechanisms involved in antitumor immunity would be important for the development of novel therapeutics. In a phase 1 study of 14 patients with follicular lymphoma, the anti–CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab was well tolerated. The overall response rate was modest at 11% (2 in 18 patients), yet the responses were durable, lasting 1 to 2 years.5 In combination with rituximab, PD-1 inhibition appears more efficacious, with overall response rates of ∼65% (50% to 54% complete response).6,7 In a phase 1 study of nivolumab, responses were observed in 4 of 10 patients with follicular lymphoma and lasted >1 year.8 These data led to the CheckMate 140 study, a prospective, open-label, multicenter phase 2 study of adult patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma following 2 or more therapies. Each therapy must have contained an anti-CD20 antibody or alkylating agent, and at least 1 therapy must have included rituximab. Ninety-two patients were enrolled and received nivolumab every 2 weeks until disease progression or toxicity. At the discretion of the treating physician, patients were permitted to remain on therapy if clinical benefit beyond progression was perceived. The primary endpoint was objective response rate by independent review committee.

After 12 months of follow-up, objective responses were minimal: 4% by independent review committee and 11% by investigator assessment. Median progression-free survival was 2.2 months, and duration of response was 11 months. Treatment-related adverse events occurred in more than half of patients. Three patients stopped therapy due to immune-mediated adverse events, and there were 3 treatment-related deaths due to respiratory failure, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and erythema multiforme.

Previous studies with more robust responses had combined anti-PD-1 antibodies with rituximab in less heavily pretreated populations, suggesting either synergistic activation of the immune response or a heterogeneous patient population. However, if follicular lymphoma pathogenesis is dependent on complex interactions between the nonmalignant tumor microenvironment and the neoplastic B cell, then interrupting immune tolerance should amplify the antitumor response. Therefore, why does PD-1 blockade monotherapy result in such limited responses? Why do a few patients have durable responses? In an attempt to answer these questions, the authors conducted several exploratory post hoc analyses to look for any biomarkers of response.

Multispectral immunofluorescence was performed on pretreatment samples from subsets of responding and nonresponding patients to identify expression of CD3, CD68, PD-1, and PD-L1. Follicular lymphoma specimens from 4 responding patients and 6 nonresponders revealed that responding patients had significantly higher infiltrating CD3+ T cells, of which most also expressed PD-1 (P = .016). Gene expression profiling was performed in 56 patients, and RNA sequencing was performed in 11 patients, to validate known immune response signatures. As demonstrated in the original pivotal study, increased expression of genes from the immune response 2 signature was strongly associated with poor progression-free survival. Patients with higher than average baseline levels of tumor-associated macrophage genes, TLR5, C3AR1, and FCGR1A were found to have increased risk of disease progression and death (see figure). Median progression-free survival for these patients was 1.9 months compared with 4.8 months in patients with low baseline gene levels (hazard ratio, 3.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.76 to 6.11; P = .001); these patients were also less likely to achieve complete or partial response (P = .048).

These results highlight important considerations for the development of future therapies in relapsed follicular lymphoma. In an era of rapidly evolving novel treatments and new Food and Drug Administration approvals for recurrent disease (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors, immunomodulator lenalidomide with rituximab, EZH-2 inhibitor tazemetostat), what is the optimal sequencing strategy? How can we develop biologically rational drug combinations to optimize efficacy and minimize toxicity? Also, most importantly, what patients are most likely to benefit from various treatments? Armand and colleagues demonstrate that the immune microenvironment has significant influence on response to therapy and prognosis in follicular lymphoma. Although efficacy of single-agent PD-1 blockade may be elusive in follicular lymphoma, there is now greater understanding into mechanisms of responsiveness that could shape future combination studies in this area.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal