In this issue of Blood, Fuchs et al performed a randomized trial in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) using either unrelated umbilical cord blood (UCB) or haploidentical related donors. They found that nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and overall survival (OS) were favored in the haploidentical treatment arm.1

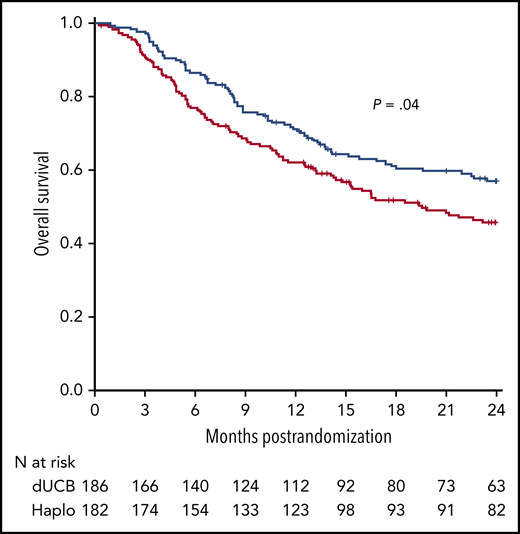

OS after transplantation according to graft source. See Figure 6D in the article by Fuchs et al that begins on page 420.

OS after transplantation according to graft source. See Figure 6D in the article by Fuchs et al that begins on page 420.

Findings from the Fuchs et al study suggest that transplantation of bone marrow (BM) from a haploidentical relative and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis that includes posttransplantation cyclophosphamide should be the preferred approach in leukemia or lymphoma patient candidates for allo-HCT who lack an HLA-matched donor because it can significantly improve OS without increased toxicity.

In the last decade, allo-HCT from a haploidentical donor and GVHD prophylaxis with posttransplantation cyclophosphamide have garnered interest with a dramatic increase in its application worldwide because of the relative simplicity of such an approach combined with good engraftment and effective GVHD control. Administration of high doses of cyclophosphamide 3 and 4 days after hematopoietic cell infusion (posttransplantation cyclophosphamide) is a key step for the success of this procedure. Posttransplantation cyclophosphamide is selectively toxic to proliferating alloreactive T cells compared with nonproliferating, nonalloreactive T cells. In addition, it is nontoxic to hematopoietic stem cells and shows decreased incidence of acute GVHD and decreased severity in animal models.2 For a long time, there were no randomized trials that evaluated the optimal stem cell source for the so-called alternative donor allo-HCT. A few noncontrolled studies reported that haploidentical allo-HCT could lead to encouraging results when compared with other donor sources.3 Even though the results are from a recent, relatively small randomized trial, they support the use of haploidentical donors vs UCB cells because of a lower incidence of NRM.4 The results from the study by Fuchs et al provide another convincing argument in the same direction, because in the haploidentical arm, the lower NRM translated into a significant OS advantage (see figure). Despite not being the primary end point of the trial, the latter finding is of paramount importance because it suggests that the use of haploidentical donors can lead to a net positive final outcome, which is usually a combination of different variables such as disease relapse, infection-related mortality, GVHD, and adverse effects.

The question now is to investigate whether haploidentical allo-HCT with reduced-intensity conditioning, an unmanipulated BM, and use of posttransplantation cyclophosphamide for GVHD prophylaxis is the best modality to use in all transplant candidates who do not have a readily available matched related or unrelated donor, and whether one can further optimize the use of such a platform. This modality is definitely proving to be an effective option to control GVHD. In the Fuchs et al trial, the incidence and severity of both acute and chronic GVHD did not differ between treatment groups. Posttransplantation cyclophosphamide for GVHD prophylaxis is likely to be a successful option in the mismatched unrelated donor allo-HCT setting.5 Although conditioning intensity may not play a significant role in older patients, the optimal timing of posttransplantation cyclophosphamide administration and the ideal stem cell graft source still remain unknown.2

The use of posttransplantation cyclophosphamide has rapidly gained popularity, but one should not ignore the potential adverse effects of high-dose cyclophosphamide in some elderly or frail patients. Another important phenomenon is that of donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies that are recognized as an important barrier against successful engraftment of haploidentical donor cells, which can affect transplant outcome.6 Moreover, although the role of HLA mismatching on unshared haplotype does not seem to be sufficiently prominent to justify its consideration in selecting a haploidentical donor, this may not be true in the case of UCB transplantation.7 In the study by Fuchs et al, each cord blood unit had to be HLA-matched to the patient at only 4 or more loci. In the future, expansion techniques may help overcome some of the limitations of cord blood transplantation (eg, engraftment rate, immune recovery kinetics, and NRM).8

The Fuchs et al randomized trial did not tackle the specific issue of maintenance after allo-HCT with the goal of reducing relapse. The incidence of recurrent disease was actually similar and was the most common cause of death in both treatment groups. Thus, independent of the issue of choice of donor, post–allo-HCT maintenance is likely to become an essential step in any allo-HCT procedure. Maintenance after allo-HCT, for example, in acute myeloid leukemia patients with FLT3-ITD mutation can lead to better OS without increased toxicity.9 However, achievement of a minimal residual disease status before allo-HCT can further complicate this issue because in patients with pretransplantation minimal residual disease, the probability of OS after receipt of a transplant from a cord-blood donor was at least as favorable as that after receipt of a transplant from an HLA-matched unrelated donor and was significantly higher than the probability after receipt of a transplant from an HLA-mismatched unrelated donor.10 Comparing the different allo-HCT procedures, including donor origin, hematopoietic cell source, preparative regimen, GVHD prophylaxis regimen, pre- and posttransplant therapies, and disease status pretransplant, has always been a challenging endeavor because many subtle and yet unidentified parameters can influence the final outcome. Thus, allo-HCT from a haploidentical donor and GVHD prophylaxis that includes posttransplantation cyclophosphamide is now established as an attractive modality in terms of feasibility, GVHD incidence and severity, and cost-effectiveness. It also provides a reasonable quality of life for patients. Despite these limitations, the results of the Fuchs et al study, combined with previous registry-based and phase 2 data, are a step in the right direction, given the observed OS benefit.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.M. has received research support and lecture honoraria from Adaptive, Amgen, Astellas, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Jazz, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, and Sanofi, all outside the scope of this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal