In this issue of Blood, Knoebl et al have prospectively evaluated the effects of emicizumab for bleeding control in 12 patients with acquired hemophilia A (AHA), a rare autoimmune bleeding disease that requires prompt diagnosis and urgent treatment.1

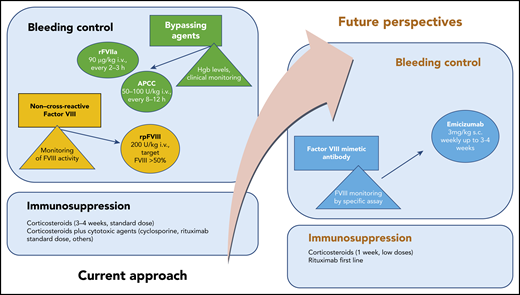

Recommended standard treatment and future perspectives in AHA. hgb, hemoglobin; i.v., intravenous; s.c., subcutaneous.

Recommended standard treatment and future perspectives in AHA. hgb, hemoglobin; i.v., intravenous; s.c., subcutaneous.

The pathogenesis of AHA, which usually occurs in adults and the elderly, consists of the production of neutralizing autoantibodies that inhibit the function of coagulation factor VIII (FVIII). In ∼50% of cases, AHA is associated with an underlying (often occult) pathology such as autoimmune disease, cancer, or graft‐versus‐host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Symptomatic patients require immediate management of acute bleeding, inhibitor suppression or eradication, and treatment of any underlying disease.

Three agents are currently licensed for bleeding control in AHA2 : recombinant activated FVII (rFVIIa), activated prothrombin complex concentrate (APCC), and recombinant porcine FVIII (rpFVIII). There are no studies that compare these treatments, so treatment choices are often made empirically. Although these drugs are effective, they are difficult to work with, especially in centers that do not have many patients with this disorder. Treatment requires frequent intravenous administration, laboratory monitoring, and careful monitoring for thromboembolic complications.

Treatment by eradication (if possible) or suppression of autoantibodies by immunosuppression may lead to complications. Data from international studies have shown that the risk of immunosuppression-related mortality, particularly as a result of infections, may be greater than the risk of fatal hemorrhages.3

Emicizumab is a recombinant, humanized, bispecific monoclonal antibody that bridges activated FIX and FX to mimic the function of missing activated FVIII. Emicizumab must be administered subcutaneously and is currently approved for prophylaxis in patients with congenital hemophilia A, both with and without inhibitors.4

Because of its mechanism of action, emicizumab may be an effective drug for controlling bleeding in patients with AHA. A recent ex vivo study5 that was performed by adding several concentrations of emicizumab to plasma from patients with AHA, has shown that the drug can restore thrombin generation. The efficacy of emicizumab after APCC or rpFVIII have failed has recently been described in case reports.6,7

The clinical experience now reported by Knoebl et al used an innovative treatment of bleeding control along with reduced-intensity immunosuppression for eradicating inhibitors, which may help overcome the current limits of combined therapy for AHA. This approach, adopted in frail patients, resulted in effective treatment without serious adverse events such as infections or thrombosis. The authors individualized therapy according to clinical response and serial laboratory measurements of coagulation FVIII.

Therefore, mimicking FVIII activity to control bleeding in AHA seems to be a promising option (see figure). Laboratory monitoring with FVIII chromogenic assays to taper treatment remains an important limitation to this approach. Other caveats from the report from Knoebl et al are the off-label administration of rituximab combined with low-dose steroids as immunosuppression and the need to avoid concomitant treatment with bypassing agents. In clinical practice, these antihemorrhagic agents are administered at the onset of disease or for breakthrough bleeding control. The combination of emicizumab and high-dose APCC has been reported to increase the risk for thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with congenital hemophilia A with inhibitors.4

This study raises several intriguing questions: Can emicizumab be administered as first-line or single-agent treatment for bleeding control in AHA? What is the optimal time interval between administration of bypassing agents and administration of emicizumab in AHA to avoid the risk of thrombosis? Does the long half-life of emicizumab expose patients to long-term adverse effects in the case of breakthrough bleeding control?

The advantages of using emicizumab are the route of administration and the prolonged interval between injections. The study by Knoebl et al further supports the role of using emicizumab, either as first-line treatment or when standard approaches for AHA prove ineffective. However, the clinical role of emicizumab vs other treatment approaches in AHA stills needs to be evaluated in a prospective clinical trial.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.S. acted as consultant for Bayer, BIOFVIIIx, Novo Nordisk, Amgen, Novartis, CSL Behring, and Takeda and received speaker fees from Kedrion, Takeda, Baxalta, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Novartis, and Amgen. M.N. acted as consultant for Bayer, BIOFVIIIx, Novo Nordisk, and Amgen and received speaker fees from Kedrion, Octapharma, Baxalta, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, and Bayer.