Key Points

The binding site of a novel inhibitory nanobody to GPVI has been mapped and shown to lie adjacent to the binding site of CRP.

The structure of GPVI in complex with an inhibitory nanobody reveals a novel domain swapped conformation implicated in platelet signaling.

Abstract

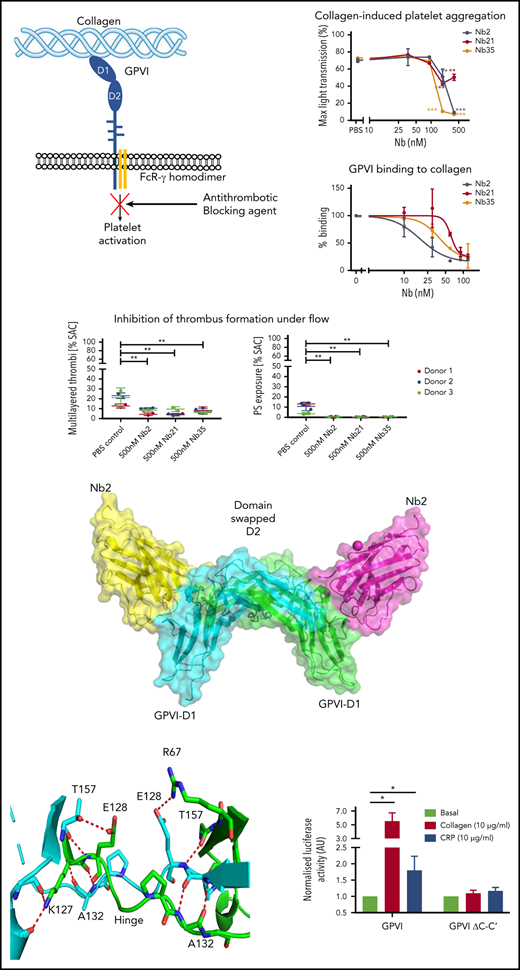

Glycoprotein VI (GPVI) is the major signaling receptor for collagen on platelets. We have raised 54 nanobodies (Nb), grouped into 33 structural classes based on their complementary determining region 3 loops, against recombinant GPVI-Fc (dimeric GPVI) and have characterized their ability to bind recombinant GPVI, resting and activated platelets, and to inhibit platelet activation by collagen. Nbs from 6 different binding classes showed the strongest binding to recombinant GPVI-Fc, suggesting that there was not a single dominant class. The most potent 3, Nb2, 21, and 35, inhibited collagen-induced platelet aggregation with nanomolar half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values and inhibited platelet aggregation under flow. The binding KD of the most potent Nb, Nb2, against recombinant monomeric and dimeric GPVI was 0.6 and 0.7 nM, respectively. The crystal structure of monomeric GPVI in complex with Nb2 revealed a binding epitope adjacent to the collagen-related peptide (CRP) binding groove within the D1 domain. In addition, a novel conformation of GPVI involving a domain swap between the D2 domains was observed. The domain swap is facilitated by the outward extension of the C-C′ loop, which forms the domain swap hinge. The functional significance of this conformation was tested by truncating the hinge region so that the domain swap cannot occur. Nb2 was still able to displace collagen and CRP binding to the mutant, but signaling was abolished in a cell-based NFAT reporter assay. This demonstrates that the C-C′ loop region is important for GPVI signaling but not ligand binding and suggests the domain-swapped structure may represent an active GPVI conformation.

Introduction

The platelet glycoprotein VI (GPVI) has been identified as an attractive antithrombotic target.1 GPVI is the major platelet signaling receptor for collagen2 and is a receptor for other ligands, including fibrin.3,4 GPVI consists of 2 N-terminal immunoglobulin-like domains (D1 and D2), a highly O-glycosylated and sialylated stalk region, a single trans-membrane spanning helix, and a short intracellular tail.5 There is a single N-glycosylation site in the D1 domain. GPVI signaling requires the FcR γ-chain homodimer, which associates through a salt bridge in the trans-membrane region of GPVI.6 Ligand binding occurs through the D1 domain7,8 and leads to phosphorylation of the 2 conserved tyrosines within the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM), present on the FcR γ-chain, by Src family kinases.9-11 Phosphorylation of the ITAM allows the recruitment of the tyrosine kinase Syk via its tandem SH2 domains and further downstream signaling.12

GPVI has been proposed to exist as a monomer and dimer in the membrane.13-15 Miura et al16 reported that recombinant dimeric GPVI, where the extracellular domains are fused to the dimeric Fc domain from immunoglobulin G (IgG), but not monomeric GPVI, binds to collagen with micromolar affinity. They proposed that the differential binding was either caused by increased avidity or the formation of a dimer-specific epitope. The latter was supported by the discovery of several dimer-specific antibodies that detected increased expression on platelet activation.13-15 Because GPVI is not present in intracellular stores in platelets, this suggests that the increase in binding is because of a conformational change as a result of dimerization.

The crystal structure of the recombinant GPVI extracellular domain has been solved for both unbound (Protein Data Bank [PDB]: 2GI7 and 5OU7) and collagen-related peptide (CRP)-bound forms (PDB: 5OU8 and 5OU9), with both structures revealing a back-to-back dimerization interface present within the D2 domain. Additionally, collagen can cluster GPVI receptors on the platelet membrane surface17 and therefore generate higher-order oligomers. GPVI signaling occurs once a critical level of clustering has been reached. The concept of a dimer-specific epitope in GPVI is not supported by the crystal structure of CRP bound to GPVI, which shows binding in the D1 domain and suggests a 1:1 stoichiometry rather than de novo formation of a binding epitope. Additionally, the site of binding of the dimer-specific antibodies and the mechanism whereby platelet activation leads to an increase in dimerization are required to establish a full understanding of the role of dimerization in platelet activation by GPVI.

Nanobodies have emerged as potential therapeutic agents that have the same antigen specificity and binding affinity as full-length antibodies, but are approximately a tenth of the size. The smaller size makes them more suitable to a variety of techniques including fluorescent imaging,18 as well as having greater tissue penetration. Nanobodies (Nbs) are comprised of a single variable domain derived from antibodies produced by camelids, which differ from human antibodies in that they do not have a light chain component and consist of 2 disulphide-linked heavy chains.19 In this report, we raised and characterized more than 50 Nbs against dimeric GPVI with the aim of producing a series of GPVI conformation-specific reagents. By solving the complex structure of GPVI with Nb2, the most potent GPVI inhibitory Nb, we revealed a novel domain swapped GPVI dimer and mapped its binding site adjacent to that of CRP.

Methods

Materials

Recombinant GPVI-Fcγ (GPVI residues 1-183) was expressed in the SigpIg+ plasmid as previously reported.20 Nbs were raised against GPVI through VIB Nanobody core (VIB Nanobody Service Facility, Brussels, Belgium), and the DNA sequences were provided in pMECS vector. Goat anti-human IgG and rabbit anti-6-His horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibodies were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Glasgow, United Kingdom) and Cambridge Bioscience (Cambridge, United Kingdom), respectively. Alexa Fluor-647 rabbit anti-6-His was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Paisley, United Kingdom). Collagen was purchased from Nicomed, and CRP was prepared as previously described.21 CRP-XL was purchased from CAMBOL Laboratories (Cambridge, United Kingdom). CD62P-phycoerythrin and isotype IgG1 κ-phycoerythrin were from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). PAR1 activating peptide (SFLLRN) was purchased from Severn Biotech (Kidderminster, United Kingdom).

PCR mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on GPVI to produce the glycosylation (N72/Q) domain swap hinge deletion mutants and thrombin cleavable Nbs. All mutagenesis was performed using a Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs) following the provided protocol. The primers used are shown in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site.

Expression and purification of recombinant GPVI

GPVI-Fc (dimeric) was expressed and purified in the SigpIg expression vector as previously described.20 The construct consists of both the D1 and D2 domains (residues 1-183) but does not contain the stalk like other GPVI-Fc constructs including Revacept.22 Monomeric GPVI was produced by cleavage of the Fc domain by incubating with human Factor Xa for 12 to 18 hours at room temperature (1 µg FXa for every 250 µg GPVI) in the presence of 2.5 mM CaCl2. Protein-A chromatography was used to separate the cleaved Fc and GPVI followed by gel filtration using a Superdex 75 26/60. All proteins were snap frozen and stored at −80°C.

Expression and purification of GPVI Nbs

All Nbs were expressed in Escherichia coli week-6 cells and contain an N-terminal PelB sequence that allows for secretion of the Nbs into the periplasmic space and C-terminal HA and His tags. Nanobodies were purified using nickel affinity chromatography. For crystallography experiments, the tags were removed by thrombin cleavage. A detailed description of the nanobody purification is provided in the supplemental Methods.

Solid-phase binding assay

Solid-phase binding assays were performed following previously documented experimental protocols.20 Wells were coated with collagen (4 µg/mL), CRP (4 µg/mL), or GPVI-Fc (1 µg/mL). HRP-conjugated anti-Fc antibody was used for the detection of GPVI-Fc binding, and HRP-conjugated anti-His was used for the detection of Nb binding.

Flow cytometry

Washed platelets (2 × 107/mL) were incubated with vehicle or PAR1 peptide (200 μM) for 3 minutes at room temperature. Platelets were then incubated with each Nbs (5 μM), and binding was detected with Alexa Fluor-647 rabbit anti-6-His antibody. Detailed description of the methods is provided in the supplemental Methods.

Platelet aggregation assay

Human platelets were freshly prepared, and aggregation was measured as previously described.20 Platelets were incubated with the Nb for 10 minutes before stimulation with 5 µg/mL collagen or 10 µg/mL CRP-XL. The effect of different concentrations of the Nb compared with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was determined using 2-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons.

Whole blood microfluidics

Whole blood (500 µL) was flown over Horm collagen I (100 μg/mL) through a Maastricht parallel flow chamber at a shear rate of 1000/s at room temperature as described previously.23 Blood was treated with either PBS or Nb (500 nM). Brightfield and fluorescence images were quantified for surface area coverage by specific semiautomated ImageJ scripts.24 Full methods are reported in the supplemental Methods.

Surface plasmon resonance

Surface plasmon resonance experiments were performed using a Biacore T200 instrument (GE Healthcare). GPVI was immobilized directly onto the CM5 chip using amine-coupling. Reference surfaces were blocked using 1 M ethanolamine, pH 8. All sensograms shown are double reference subtracted, and at least 2 replicates were injected per cycle, as well as experimental replicates of n = 3. Experiments were performed at 25°C with a flow rate of 30 μL/min in HBS-EP running buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% v/v surfactant P20). Each concentration of Nb2 was run as follows: 120-second injection, 900-second dissociation. Kinetic analysis was performed using the Biacore T200 Evaluation software using a global fitting to a 1:1 binding model.

Crystallization and structure determination

Crystallization was performed using the GPVI N72Q variant and untagged Nb2. Both proteins were mixed at 75 µM, and the complex was purified using a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL gel filtration column equilibrated in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and 140 mM NaCl. The complex was concentrated to 5 mg/mL. Crystals were generated in 0.2 M calcium acetate, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, and 18% PEG8K, and diffraction data were collected at the Diamond Light Source i24 Beamline.

The CCP4 software suite was used for structure determination. Molecular replacement was performed in PHASER using 2GI7 and 5TP3 as templates. This was followed by model building in Crystallographic Object-Oriented Toolkit (COOT) and multiple rounds of refinement in Refinement of Macromolecular Structures (REFMAC). Data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Space group | P 21 21 21 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 69.91 84.75 124.04 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

| Resolution (Å) | 84.57-2.5 |

| Rmerge | 0.122 (0.595)* |

| I/σI | 8.67 (2.69)* |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (98.6)* |

| Redundancy | 6.3 (6.4)* |

| Wavelength | 0.96864 Å |

| Refinement | |

| No. of reflections | 26 173 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 0.176/0.232 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 4664 |

| Ca2+ | 1 |

| Water | 271 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 43.91 |

| Metal | 24.33 |

| Water | 41.78 |

| RMS deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0084 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.568 |

| Data collection . | Value . |

|---|---|

| Space group | P 21 21 21 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 69.91 84.75 124.04 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

| Resolution (Å) | 84.57-2.5 |

| Rmerge | 0.122 (0.595)* |

| I/σI | 8.67 (2.69)* |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (98.6)* |

| Redundancy | 6.3 (6.4)* |

| Wavelength | 0.96864 Å |

| Refinement | |

| No. of reflections | 26 173 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 0.176/0.232 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 4664 |

| Ca2+ | 1 |

| Water | 271 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 43.91 |

| Metal | 24.33 |

| Water | 41.78 |

| RMS deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0084 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.568 |

Rfree, computed as in Rwork, but only for (5%) randomly selected reflections, which were omitted in refinement, calculated using Refinement of Macromolecular Structures (REFMAC); Rmerge, Σh Σi| <Ih> − Ih,i|/Σh Σi Ih,I, where I is the observed intensity and <Ih> is the average intensity of multiple observations from symmetry-related reflections calculated; Rwork, Sum(h) ||Fo|h − |Fc|h|/Sum(h)|Fo|h, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Nuclear factor of activated T-cell reporter assay

The nuclear factor of activated T-cell (NFAT) reporter assay was used for GPVI signaling detection, following the protocol documented by Tomlinson et al.25 DT-40 cells were transfected with 2 µg each of full-length GPVI, FcR-γ chain, and NFAT-controlled luciferase reporter construct. Transfected cells were incubated with 100 nM of each Nb for 15 minutes, followed by stimulation on the addition of 10 µg/mL collagen or CRP. All readouts were expressed as a percentage of the signal from collagen alone. GPVI surface expression was confirmed by cell-labeling samples with HY101 antibody followed by anti-mouse Alexa Fluor-647 secondary antibody staining and performing flow cytometry. The samples were acquired (FL1 and 4) and analyzed using an Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Statistics

Results are shown as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were performed with n = 3, whereas NFAT assays were performed with n = 5. A 2-tailed Student t test was used, and P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Testing of Nbs on recombinant GPVI

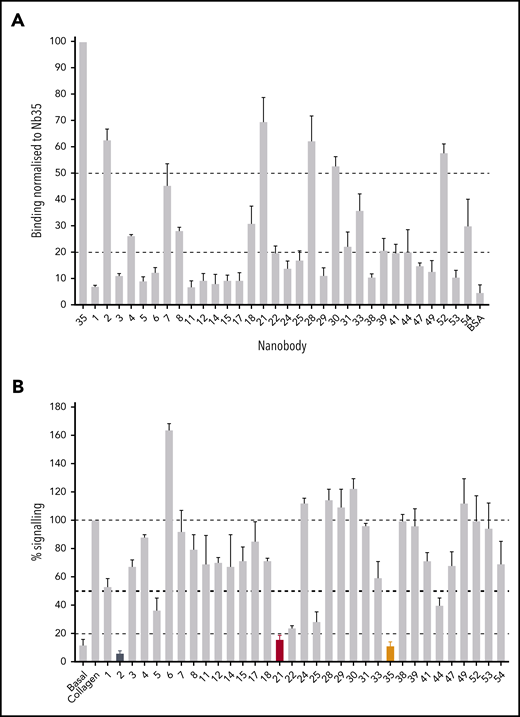

The recombinant GPVI used for immunization and testing consisted of the extracellular D1 and D2 domains fused with the Fc domain from IgG. Immunization with GPVI-Fc yielded 54 distinct Nb sequences. The Fc domain was used to test whether the Nbs recognize this region. The 54 Nbs were categorized into 33 distinct binding classes based on their complementary determining region 3 (CDR3) sequence, which is the region that confers ligand specificity.26 Nbs with CDR3 regions with >80% homology were considered in the same binding class. Nbs (1 µM) from each binding class were tested for their ability to recognize a recombinant GPVI-Fc–coated surface (Figure 1A). The degree of Nb binding varied between classes and could be categorized into strong (>50%), moderate (>20%), and weak binders (<20%). Strong binders included Nb2, 21, 35, and 52. Moderate binders included Nb7, 18, 28, and 54. All other Nbs were considered weak binders.

Testing of Nb binding and inhibition of GPVI signaling. (A) Surface binding assay of 1 Nb (100 nM) from each binding class to a GPVI-Fc–coated surface. All binding results have been normalized to Nb35, which gave the highest readout. Binding of each Nb to the Fc domain-coated surface was tested and subtracted from the GPVI-Fc readings. Binding was detected using HRP-conjugated anti-His antibody. The average binding of all the nanobodies to bovine serum albumin represents a nonspecific binding control. Data represent mean values of 3 experiments ± SD. (B) NFAT reporter assay of GPVI- and FcRγ-transfected DT40 cells stimulated by collagen (10 µg/mL) in the presence of the Nbs (100 nM). Results are plotted as a percentage of total signaling in the presence of collagen only. Dotted lines represent 100%, 50%, and 20% signaling levels, and nb2, 21, and 35 are colored in black, red, and orange, respectively. Data represent mean values of 3 experiments performed in triplicate ± SD.

Testing of Nb binding and inhibition of GPVI signaling. (A) Surface binding assay of 1 Nb (100 nM) from each binding class to a GPVI-Fc–coated surface. All binding results have been normalized to Nb35, which gave the highest readout. Binding of each Nb to the Fc domain-coated surface was tested and subtracted from the GPVI-Fc readings. Binding was detected using HRP-conjugated anti-His antibody. The average binding of all the nanobodies to bovine serum albumin represents a nonspecific binding control. Data represent mean values of 3 experiments ± SD. (B) NFAT reporter assay of GPVI- and FcRγ-transfected DT40 cells stimulated by collagen (10 µg/mL) in the presence of the Nbs (100 nM). Results are plotted as a percentage of total signaling in the presence of collagen only. Dotted lines represent 100%, 50%, and 20% signaling levels, and nb2, 21, and 35 are colored in black, red, and orange, respectively. Data represent mean values of 3 experiments performed in triplicate ± SD.

We used an NFAT reporter assay to investigate GPVI signaling in a transfected cell line (Figure 1B). This assay takes advantage of ITAM signaling through Src and Syk tyrosine kinases, which results in NFAT-dependent expression of a luciferase reporter.25 Collagen stimulated an 8.3 ± 2.8–fold increase in NFAT activity. Nbs 2, 21, and 35 (100 nM) inhibited the increase by greater than 80%, and Nbs 5, 22, 25, and 44 inhibited this by more than 50%. Several Nbs, Nbs 6, 24, 28 to 30, and 49, increased the response to collagen, and the remainder either had no effect or resulted in inhibition <50%. The marked potency of Nbs 2, 21, and 35 is in line with their high affinity for binding to GPVI (Figure 1A).

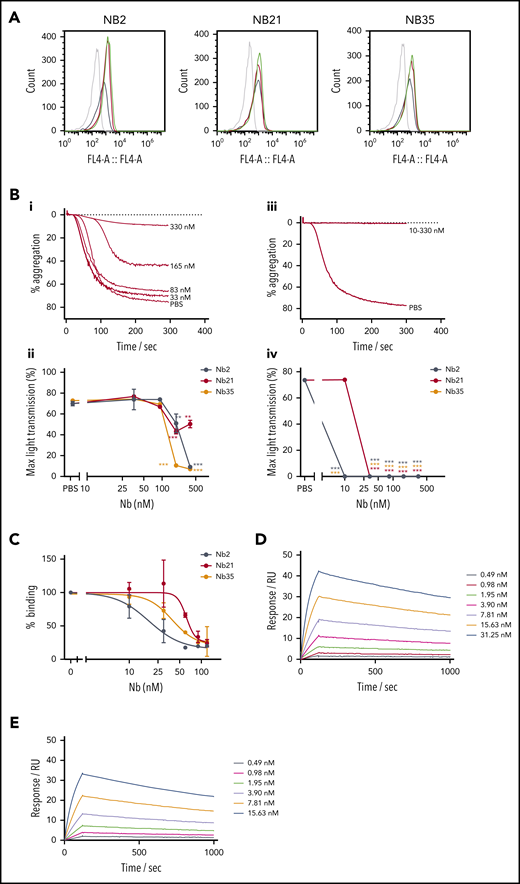

Evaluation of Nbs 2, 21, and 35 as blocking agents

The most potent Nbs, Nb2, 21, and 35, were further tested in their ability to inhibit GPVI function. First, their binding to platelets was tested using flow cytometry. All 3 Nbs exhibited similar binding to resting and activated platelets in the presence of PAR1 activating peptide (200 μM; Figure 2A), suggesting that they recognize both monomeric and dimeric GPVI. Previously, Jung et al14 reported that thrombin stimulates dimerization of GPVI. Further studies were performed on these Nbs to investigate the concentration response relationship in binding to GPVI and for inhibition of platelet aggregation and adhesion under flow. Nbs 2, 21, and 35 inhibited platelet aggregation to collagen (5 μg/mL) and CRP (10 μg/mL) with half maximal inhibitor concentration (IC50) values of 172, 85, and 115 nM for collagen and 1, 22, and 1 nM for CRP, respectively (Figure 2B). The differential IC50 values is likely to reflect binding of collagen to a second receptor on platelets, integrin α2β1.

Further testing of top inhibitory Nbs of GPVI. (A) Nbs 2, 21, and 35 (5 µM) binding to washed platelets in the presence or absence of 200 μM PAR1 by flow cytometry. Gray histograms show unstained washed platelets, black histograms show nonspecific staining of anti-His alexafluor647 secondary, red histograms show nanobody binding to resting platelets, and green histograms show nanobody binding to PAR1 peptide–activated platelets. (B) Platelet aggregation in response to (i-ii) 5 µg/mL collagen and (iii-iv) 10 µg/mL CRP in the presence of Nb2, 21, and 35. (i, iii) Representative aggregation curves for Nb2. (ii, iv) Maximum aggregation values for all Nbs. IC50 values of 172, 85, and 115 nM for collagen and 1, 22, and 1 nM for CRP were determined for Nb2, 21, and 35, respectively. The effect of different concentrations of the nanobody compared with the vehicle (PBS) was determined using 2-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons. (C) Solid-phase binding assay showing GPVI-Fc (100 nM) displacement from a collagen surface in the presence of increasing concentration Nb2, 21, and 35, with IC50 values of 18, 62, and 39 nM, respectively. Data represent mean values of 3 ± SD. (D-E) SPR data showing Nb2 at a range of concentrations binding to (D) GPVI-Fc and (E) GPVI immobilized on a surface. The binding affinity was determined by kinetic analysis with calculated KD values of 0.7 ± 0.03 nM for GPVI-Fc and 0.58 ± 0.06 nM for GPVI.

Further testing of top inhibitory Nbs of GPVI. (A) Nbs 2, 21, and 35 (5 µM) binding to washed platelets in the presence or absence of 200 μM PAR1 by flow cytometry. Gray histograms show unstained washed platelets, black histograms show nonspecific staining of anti-His alexafluor647 secondary, red histograms show nanobody binding to resting platelets, and green histograms show nanobody binding to PAR1 peptide–activated platelets. (B) Platelet aggregation in response to (i-ii) 5 µg/mL collagen and (iii-iv) 10 µg/mL CRP in the presence of Nb2, 21, and 35. (i, iii) Representative aggregation curves for Nb2. (ii, iv) Maximum aggregation values for all Nbs. IC50 values of 172, 85, and 115 nM for collagen and 1, 22, and 1 nM for CRP were determined for Nb2, 21, and 35, respectively. The effect of different concentrations of the nanobody compared with the vehicle (PBS) was determined using 2-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons. (C) Solid-phase binding assay showing GPVI-Fc (100 nM) displacement from a collagen surface in the presence of increasing concentration Nb2, 21, and 35, with IC50 values of 18, 62, and 39 nM, respectively. Data represent mean values of 3 ± SD. (D-E) SPR data showing Nb2 at a range of concentrations binding to (D) GPVI-Fc and (E) GPVI immobilized on a surface. The binding affinity was determined by kinetic analysis with calculated KD values of 0.7 ± 0.03 nM for GPVI-Fc and 0.58 ± 0.06 nM for GPVI.

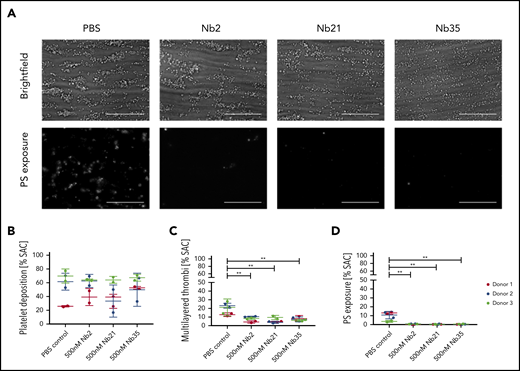

In a solid-phase binding assay, all 3 Nbs blocked the binding of GPVI-Fc (100 nM) to a collagen surface with IC50 values for Nbs 2, 21, and 35 of 18, 61, and 39 nM, respectively (Figure 2C). The binding affinity of the most potent of the 3 Nbs, Nb2, to immobilized GPVI and GPVI-Fc was determined by surface plasmon resonance (SPR), with a calculated equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) of 0.7 ± 0.03 and 0.58 ± 0.06 nM for GPVI-Fc and GPVI, respectively (Figure 2D-E). This binding affinity is approximately 25-fold higher than that of the full-length inhibitory GPVI antibody 9012.27 The similar binding affinities to monomeric and dimeric GPVI is consistent with the observation that binding of Nb2 to platelets is not altered on thrombin stimulation. To assess the effect of the most potent anti-GPVI nanobodies on platelet activation and subsequent thrombus formation, a whole blood flow adhesion assay was performed. Blood from healthy donors was preincubated with either PBS or 500 nM Nb2, 21, or 35 for 10 minutes, thrombin was inhibited, and then the blood was recalcified and flown over collagen at a shear rate of 1000/s. Quantitative analysis of the images demonstrated that all 3 Nbs had no significant effect on platelet adhesion under flow (Figure 3B) but that they inhibited the formation of multilayered aggregates (Figure 3C). The platelets that did adhere also had abrogated phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure relative to untreated controls (Figure 3D). The abolition of aggregation and PS exposure, but not adhesion, is consistent with results in patients who are GPVI deficient.23

Effect of anti-GPVI Nbs in whole blood microfluidics. (A) Representative images of whole blood perfused at an arterial shear rate (1000/s) over Horm collagen I in the presence of either PBS or 500 nM Nb 2, 21, or 35. Adhered platelets and platelet aggregates were imaged in brightfield after 3.5 minutes of flow. Platelets were labeled with Annexin V AF568 to assess PS exposure. All images were taken on an EVOS AMF4300 using a 60×, 1.42 NA oil objective. Data are representative of 2 runs for each of 3 donors per treatment. Scale bars, 50 µm. (B-D) Quantitative analysis of the images assessed the effect of the Nbs on percentage of total surface area covered by platelets (B), multilayered thrombi (C), and platelets exposing PS (D). Data points are individual runs for each of 3 donors (shown in different colors) per treatment (mean ± SD). Unpaired Student t test with Mann-Whitney correction was used to test for statistical significance: **P < .005. SAC, surface area coverage.

Effect of anti-GPVI Nbs in whole blood microfluidics. (A) Representative images of whole blood perfused at an arterial shear rate (1000/s) over Horm collagen I in the presence of either PBS or 500 nM Nb 2, 21, or 35. Adhered platelets and platelet aggregates were imaged in brightfield after 3.5 minutes of flow. Platelets were labeled with Annexin V AF568 to assess PS exposure. All images were taken on an EVOS AMF4300 using a 60×, 1.42 NA oil objective. Data are representative of 2 runs for each of 3 donors per treatment. Scale bars, 50 µm. (B-D) Quantitative analysis of the images assessed the effect of the Nbs on percentage of total surface area covered by platelets (B), multilayered thrombi (C), and platelets exposing PS (D). Data points are individual runs for each of 3 donors (shown in different colors) per treatment (mean ± SD). Unpaired Student t test with Mann-Whitney correction was used to test for statistical significance: **P < .005. SAC, surface area coverage.

Nb2 binds close to the CRP binding epitope and reveals a novel domain-swapped dimeric GPVI structure

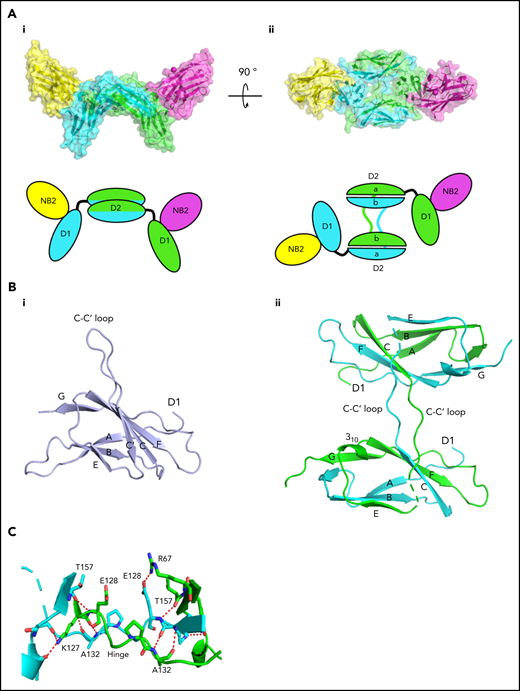

We next aimed to solve the crystal structure of the most potent of the Nbs, Nb2, with recombinant GPVI. Crystallization of dimeric GPVI-Fc was not successful so monomeric GPVI was used. For these studies, the single N-glycosylation site at N72 was mutated to glutamine (GPVI NQ). GPVI NQ was mixed with Nb2 in a 1:1 ratio at a concentration of 75 μM and purified as a complex by gel filtration (supplemental Figure 4). The crystal structure of this complex was solved with a resolution of 2.2 Å. The structure revealed the binding epitope of Nb2 and a novel GPVI dimer conformation (Figure 4). The dimer interface consisted of 2 domain-swapped D2 domains formed through the extension of the C-C′ loop region (labeling in accordance with Horii et al28 ). This extended loop forms a domain swap hinge that extends outward and folds with an adjacent D2 (Figure 4B). This is in stark contrast with the back-to-back D2 dimer reported in previous crystal structures.28 Additional novel features within the D2 structure are shown in Figure 4B-C. No observed electron density was found between residues K135 and R142, which in previous structures forms the C-terminal end of the C-C′ hinge loop and the start of the C′ β-strand. In addition, there is a slight shift within the E β-strand, which in previous structures is made up of residues I147 to V150 but is formed by residues S144 to I148 in the domain-swapped structure. The loop between the E and F β-strands forms a short 310 helix that has not been observed in other D2 structures but is present within D1. These small structural changes are likely the result of the extension of the hinge loop toward the adjacent subunit and subsequent destabilization of the C′ β-strand.

Crystallization of Nb2 and GPVI. (A) Structure of Nb2 binding to GPVI. (i) Side view of the GPVI-Nb2 structure. (ii) Top-down view illustrating the domain swap hinge region. A cartoon representation is shown below each figure. Separate GPVI protein subunits are shown in green and cyan, and both Nb2 proteins are shown in yellow and pink. The domain-swapped D2 domains are labeled D2a and D2b for the N- and C-terminal D2 regions, respectively. (B) Comparison of the D2 domains from the non–domain-swapped structure (PDB: 2GI7) (i) and the domain-swapped structure (ii) with major features highlighted. This highlights the differences within the C-C′ hinge region, the C′ β-strand where no electron density was observed for the domain-swapped structure, and the presence of a 310 helix between βE and F. (C) Enlarged view of the D2 domain-swapped hinge region with the hinge loops colored in green and cyan and the interchain polar contacts, which stabilize this region, shown as red dashes.

Crystallization of Nb2 and GPVI. (A) Structure of Nb2 binding to GPVI. (i) Side view of the GPVI-Nb2 structure. (ii) Top-down view illustrating the domain swap hinge region. A cartoon representation is shown below each figure. Separate GPVI protein subunits are shown in green and cyan, and both Nb2 proteins are shown in yellow and pink. The domain-swapped D2 domains are labeled D2a and D2b for the N- and C-terminal D2 regions, respectively. (B) Comparison of the D2 domains from the non–domain-swapped structure (PDB: 2GI7) (i) and the domain-swapped structure (ii) with major features highlighted. This highlights the differences within the C-C′ hinge region, the C′ β-strand where no electron density was observed for the domain-swapped structure, and the presence of a 310 helix between βE and F. (C) Enlarged view of the D2 domain-swapped hinge region with the hinge loops colored in green and cyan and the interchain polar contacts, which stabilize this region, shown as red dashes.

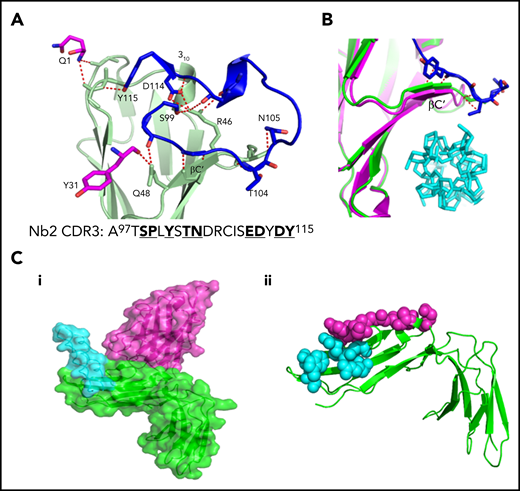

The Nb2 binding site was mapped within D1 adjacent to the CRP binding site. Residues involved in the Nb2-GPVI binding interface are shown in Figure 5A. The primary interaction interface is found toward the top of the CRP binding groove within the D1 C′ β-sheet and 310 helix found between βE and F strands. This forms a primary binding pocket and polar contacts between nanobody residues within the CDR3 loop with GPVI residues S45-Y47 found within the D1 C’ β-sheet, and S61 found in the short 310 helix. Additional contacts within the primary binding site are made between Nb2 CDR1 residue Y31 and GPVI residue Q48. A secondary interaction pocket is located away from the CRP binding groove made by residues Q1 and Y115 of Nb2 interacting with E21, P56, and A57 of GPVI. A summary of binding residues is presented in supplemental Table 2. The GPVI binding site lies entirely within the CDR3 loop of Nb2 apart from Q1 and Y31. The Nb2 binding site is adjacent to the CRP binding interface (Figure 5B) with the CDR2 loop extending toward the CRP binding site, which would induce steric clashes between both ligands. In addition, the binding of the CDR3 loop to the short C′ β-sheet of D1 the top of the CRP binding groove induces a small shift of approximately 1.5 Å, which causes a small distortion of the groove (Figure 5B). A Ca2+ cation can be found bridging 2 Nb2 subunits, through interactions with the side chain carboxyl group of E6 and peptide backbone carbonyl of G119, and 2 water molecules resulting in an octahedral Ca2+ ion coordination. In summary, the crystallization of the GPVI–Nb2 complex has revealed that the Nb2 binding site lies in close proximity to the CRP binding site and induces a small conformational change in D1. The structure also reveals a domain swap between the D2 domains.

Site of interaction of GPVI with Nb2 and CRP. (A) Enlarged view of the GPVI–Nb2 binding interface. GPVI is colored in light green, and Nb2 binding residues in the CDR3 loop are colored in blue and non-CDR3 residues in pink. Red dashed lines indicate polar contacts made between GPVI and Nb2 residues. The full CDR3 sequence for Nb2 is provided underneath the structure with binding residues highlighted in bold. (B) Enlarged view of the CRP binding groove of the CRP-bound GPVI structure (pink) and Nb-bound structure (green), with CRP shown in cyan and Nb2 cdr3 residues 100 to 105 shown in blue. The binding of Nb2 toward the top of the binding groove results in a shift of the βC′ sheet, resulting in a small distortion of the CRP binding groove. (C) Locations of the known Nb2 and CRP binding sites on GPVI. (i) Surface representation of Nb2 (pink) modeled onto the GPVI–CRP complex structure (PDB: 5OU8), colored in green and cyan, respectively, revealing the 2 nonoverlapping but closely situated binding sites. (ii) Nb2 and CRP binding residues mapped as pink and cyan spheres, respectively, on the structure of GPVI.

Site of interaction of GPVI with Nb2 and CRP. (A) Enlarged view of the GPVI–Nb2 binding interface. GPVI is colored in light green, and Nb2 binding residues in the CDR3 loop are colored in blue and non-CDR3 residues in pink. Red dashed lines indicate polar contacts made between GPVI and Nb2 residues. The full CDR3 sequence for Nb2 is provided underneath the structure with binding residues highlighted in bold. (B) Enlarged view of the CRP binding groove of the CRP-bound GPVI structure (pink) and Nb-bound structure (green), with CRP shown in cyan and Nb2 cdr3 residues 100 to 105 shown in blue. The binding of Nb2 toward the top of the binding groove results in a shift of the βC′ sheet, resulting in a small distortion of the CRP binding groove. (C) Locations of the known Nb2 and CRP binding sites on GPVI. (i) Surface representation of Nb2 (pink) modeled onto the GPVI–CRP complex structure (PDB: 5OU8), colored in green and cyan, respectively, revealing the 2 nonoverlapping but closely situated binding sites. (ii) Nb2 and CRP binding residues mapped as pink and cyan spheres, respectively, on the structure of GPVI.

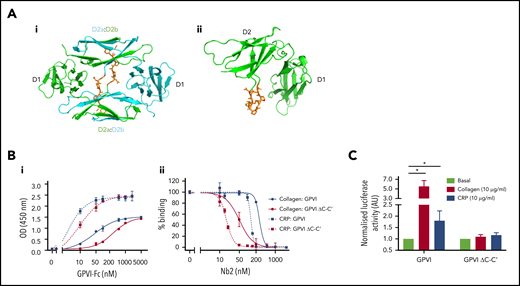

Truncating the domain swap hinge region prevents GPVI signaling but not ligand binding

The domain-swapped structure shows a critical role for the C-C′ hinge region, which, in the original structure of GPVI, was modeled as an unstructured loop region in 1 of the 2 GPVI monomers and was not resolved in the other. In a more recent crystal structure of the GPVI dimer in complex with CRP, this hinge region was removed, which means that the domain swap would not have been possible, and the structure of GPVI was the same as the original structure (PDB: 5OU7). The position of the hinge region in the nanobody bound structure and original GPVI structure is shown in Figure 6A.

The domain swap is required for signaling but not ligand binding. (Ai-ii) Crystal structures of the nanobody bound and original unbound GPVI structures, respectively, highlighting the region of the C-C′ hinge loop (orange) deleted for mutation studies. The domain-swapped structure contains 2 GPVI subunits colored in green and cyan, whereas only 1 subunit is shown for the original GPVI structure. The domain-swapped D2 domain is labeled D2a and D2b for the N- and C-terminal D2 regions, respectively. (Bi) Solid-phase binding assay comparing the dose-dependent binding of GPVI-Fc and GPVI-Fc ΔC-C′ to a collagen and CRP-coated surface. Respective EC50 values of 42 and 294 nM were calculated for GPVI and GPVI ΔC-C′ binding to collagen and 2 and 9 nM for CRP, respectively. (Bii) Binding of GPVI-Fc and GPVI-Fc ΔC-C′ to a collagen and CRP-coated surface and subsequent displacement by increased concentrations of Nb2. GPVI (500 nM) was used for collagen, and 100 nM GPVI was used for CRP. Data are normalized against the highest and lowest concentrations of Nb2 and are expressed as percent binding. Respective IC50 values of 268 and 51 nM were calculated for GPVI and GPVI ΔC-C′ binding to collagen and 132 and 17 nM for CRP. Data represent mean values of 3 experiments ± SD. (C) NFAT reporter assay of DT40 cells transfected with the FcR-γ chain and either full-length GPVI wild type or hinge mutant. Luciferase activity was reported for nonstimulated and CRP- and collagen-stimulated cells. Data represent mean values of 5 experiments performed in triplicate ± SD, and values are normalized against the respective basal levels. A Student 2-tailed t test was used to determine significance between basal and stimulated values.

The domain swap is required for signaling but not ligand binding. (Ai-ii) Crystal structures of the nanobody bound and original unbound GPVI structures, respectively, highlighting the region of the C-C′ hinge loop (orange) deleted for mutation studies. The domain-swapped structure contains 2 GPVI subunits colored in green and cyan, whereas only 1 subunit is shown for the original GPVI structure. The domain-swapped D2 domain is labeled D2a and D2b for the N- and C-terminal D2 regions, respectively. (Bi) Solid-phase binding assay comparing the dose-dependent binding of GPVI-Fc and GPVI-Fc ΔC-C′ to a collagen and CRP-coated surface. Respective EC50 values of 42 and 294 nM were calculated for GPVI and GPVI ΔC-C′ binding to collagen and 2 and 9 nM for CRP, respectively. (Bii) Binding of GPVI-Fc and GPVI-Fc ΔC-C′ to a collagen and CRP-coated surface and subsequent displacement by increased concentrations of Nb2. GPVI (500 nM) was used for collagen, and 100 nM GPVI was used for CRP. Data are normalized against the highest and lowest concentrations of Nb2 and are expressed as percent binding. Respective IC50 values of 268 and 51 nM were calculated for GPVI and GPVI ΔC-C′ binding to collagen and 132 and 17 nM for CRP. Data represent mean values of 3 experiments ± SD. (C) NFAT reporter assay of DT40 cells transfected with the FcR-γ chain and either full-length GPVI wild type or hinge mutant. Luciferase activity was reported for nonstimulated and CRP- and collagen-stimulated cells. Data represent mean values of 5 experiments performed in triplicate ± SD, and values are normalized against the respective basal levels. A Student 2-tailed t test was used to determine significance between basal and stimulated values.

Because the hinge truncated variant of GPVI is still able to bind CRP, as shown in the crystal structure, this provides a mechanism of testing the functional significance of the domain swapped structure. We therefore used site directed mutagenesis to truncate the length of hinge region (amino acids G129DPAPYKN136) and prevent formation of the domain swapped dimer configuration both in a recombinant GPVI construct and in full-length GPVI (named ΔC-C′). A solid-phase binding assay showed that GPVI-Fc ΔC-C′ bound to both collagen- and CRP-coated surfaces in a concentration-dependent manner. Calculated half maximal effective concentration (EC50) values for binding to collagen were 294 nM compared with 42 nM for GPVI-Fc and 9 nM compared with 2 nM for GPVI-Fc binding to CRP (Figure 6Bi). Nb2 showed an increased potency for displacement of the interaction of GPVI-Fc ΔC-C′ to collagen and CRP with an IC50 of 51 and 17 nM, respectively, compared with 268 and 132 nM for GPVI-Fc wild type (Figure 6Bii), reflecting the lower affinity of collagen and CRP for the mutant. This suggests that the collagen and CRP binding site has undergone a small conformational change that results in reduced ligand binding. Nb2 binding to this mutant was comparable to GPVI-Fc with a KD of 2.6 ± 0.4 nM as determined by SPR (supplemental Figure 6). Interestingly, collagen and CRP were unable to activate full-length GPVI ΔC-C′ construct expressed in a cell line using the NFAT reporter assay (Figure 6C). These results provide evidence that the hinge region may be required for maintaining the conformation of the ligand-binding domain and for signaling.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a range of Nbs to GPVI and characterized these using a variety of assays. These studies show the following: (1) a diverse range of Nbs with sequence differences in their CDR3 domains bind to GPVI; (2) the most potent of these, Nb2, 21, and 35, bind with nanomolar affinity and block collagen-induced NFAT activation, platelet aggregation, and thrombus formation under flow; (3) a crystal structure reveals Nb2 binds to a site on GPVI that is adjacent to the CRP binding site; and (4) Nb2 forms a complex with a novel domain-swapped GPVI dimer. Together, the Nbs form a library of agents for probing GPVI function in platelets. It should be noted that all Nbs, excluding Nbs 6, 11, and 53, were directly displaced by Nb2 in a competition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (data not shown), which suggests most of the Nbs may bind close to the Nb2 binding site on D1.

The presence of a domain-swapped GPVI dimer offers a new scaffold to examine GPVI dimerization. A critical feature of the domain swap is the extension of the C-C′ hinge. The construct used to solve the complex crystal structure with CRP was also missing the C-C′ hinged loop region, and therefore a domain swapped dimer could not be formed. The construct used by Horii et al for the original GPVI crystal structure did include the hinge loop, but the domain swap was not observed, and the back-to-back dimer conformation was instead reported. The different conformations between the structure of Horii et al and the domain-swapped structure we describe here could be caused by the different crystallization conditions used between experiments. A second explanation is that the nanobody stabilizes the domain swapped conformation in the crystal and represents just 1 potential dimeric conformation adopted by GPVI. Dimerization of recombinant D1, D2 has not been detected in solution,28 and the formation of stable dimers likely requires additional contact regions such as the disulphide formed within the intracellular tail.29

By producing a GPVI deletion mutant with a shortened hinge region, we attempted to address the functional significance of the domain-swapped GPVI conformation. In the original non–domain-swapped structure (PDB: 2GI7), the C-C′ loop does not form a domain swap hinge but forms a disordered loop that points away from the rest of the protein (Figure 5B); therefore, shortening this loop would not have a significant impact on GPVI structure unless a domain swap is formed. This is supported by a previously solved structure of GPVI without the C-C′ loop (PDB: 5OU7) that shows no significant conformational changes within D1 or D2 compared with the original structure. Strikingly, collagen and CRP were unable to activate the hinge mutant, which, although not direct evidence for the presence of a domain swap, does suggests that the domain swap may be important for GPVI signaling. Although binding to CRP and collagen is slightly reduced in the mutant, binding still occurs, and the reduction in binding affinity would not result in complete abolition of signaling. However, these results do not definitively prove the existence of a domain swap. The hinge region may have alternative functions such as being an allosteric modulator of GPVI on ligand binding. The inability to detect recombinant GPVI dimers in solution is a limiting factor for this study, and other cell line techniques such as nanoBRET30 would need to be performed to confirm the role of the hinge region in GPVI dimerization.

The crystal structure of Nb2-bound GPVI reveals that Nb2 interacts with the top of the CRP binding groove and, although not directly overlapping with the CRP binding site, is close enough to sterically hinder the binding to collagen. Inhibition of collagen binding by Nb2 is likely, however, a combination of steric clashes between closely positioned binding sites and the distortion of the CRP binding groove (Figure 5C), indicative of a mixed mode allosteric and competitive inhibitor. Nb2 therefore provides a new scaffold that can be used for the development of antithrombotic drugs to treat cardiovascular disease.

In summary, our results provide evidence that GPVI signaling requires an active domain swapped conformation of GPVI and offers a new mechanistic insight into GPVI activation. Full-length structures of GPVI in both resting and activated states are required to confirm the role of the domain-swapped conformation in GPVI activation.

For original data, please contact a.slater@bham.ac.uk.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded, in whole, or in part, by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (204951/B/16/Z). A Creative Commons (CC-BY) license is applied to the Association for Accessible Medicines arising from this submission, in accordance with the grant’s open access conditions. S.P.W. is a British Heart Foundation Professor (CH 03/003). The authors acknowledge the Diamond Light Source for provision of synchrotron radiation in using the Beamline I04. N.J.J. is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant 766118 and is registered in the programs of Maastricht and University of Birmingham.

Authorship

Contribution: A.S. performed experiments, generated new constructs, performed X-ray crystallography, and wrote and edited manuscript; Y.D. expressed and performed characterization experiments on all the nanobodies; J.C.C. performed flow cytometry experiments; N.J.J. performed flow studies on thrombus formation and edited the manuscript; E.M.M. performed SPR experiments; F.A. performed platelet aggregation assays; M.R.T. provided supervision and funding; R.A.S.A. contributed to study design and supervision; A.B.H. provided GPVI constructs and training for GPVI production; N.S.P. contributed to study design, provided supervision, and edited the manuscript; J.E. provided X-ray crystallography supervision, funding, and wrote and edited the manuscript; S.P.W. provided supervision, funding, and study design and concept, reviewed the data, and wrote and edited manuscript; and all authors read the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alexandre Slater, Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, IBR Bldg, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; e-mail: a.slater@bham.ac.uk; Steve P. Watson, Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, IBR Bldg, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; e-mail: s.p.watson@bham.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal