In this issue of Blood, Mato et al report the results of an open-label multicenter phase 2 study of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor umbralisib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who were intolerant of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) or inhibitors they had received earlier.1

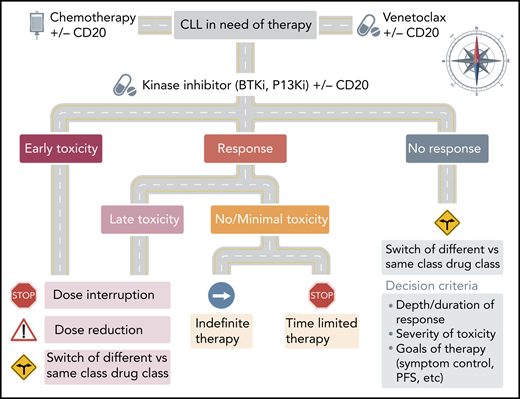

Roadmap for use of KIs in CLL. The decision to continue or switch KI therapy in CLL is based on the severity and timing of previous toxicity and quality of response. In patients with early toxicity or responding patients who have delayed non–life-threatening AEs, consideration can be given to dose interruption or reduction. In patients who progress or develop severe or chronic toxicity, alternate class or alternate target inhibitor should be considered.

Roadmap for use of KIs in CLL. The decision to continue or switch KI therapy in CLL is based on the severity and timing of previous toxicity and quality of response. In patients with early toxicity or responding patients who have delayed non–life-threatening AEs, consideration can be given to dose interruption or reduction. In patients who progress or develop severe or chronic toxicity, alternate class or alternate target inhibitor should be considered.

Over the last several years, several small-molecule kinase inhibitors (KIs) were approved in various indications across B-cell malignancies. Specifically, the integration of BTK inhibitors (BTKi’s) and PI3K inhibitors (PI3Ki’s) alone and in combination with anti-CD20 therapy into CLL treatment regimens resulted in a paradigm shift away from traditional chemotherapy-based backbones as preferred management. This shift resulted in improved outcomes across a broad swath of patients in nearly every measurable outcome, including overall survival (OS). Recently, long-term follow-up of registration-enabling studies for BTKi’s and PI3Ki’s were published. In untreated patients with CLL who were older than age 65 years, single-agent ibrutinib resulted in a 70% 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) and an 83% 5-year OS.2 Mature reports of idelalisib plus rituximab in relapsed CLL also demonstrated a persistent PFS benefit over rituximab alone.3 Not surprisingly, the phenomenal activity observed in these and other early studies resulted in rapid development of next-generation BTKi’s and PI3Ki’s with slightly different mechanisms of action, target specificity, method of delivery, and pharmacokinetics.

However, as experience with prolonged exposure to these first agents grew, it became clear that each drug was associated with rare, but unique and often serious adverse events (AEs). In addition to well-characterized rash and low-grade bleeding and bruising, ibrutinib is also associated with an increasing risk of atrial fibrillation. In a pooled analysis of more than 1500 patients treated with ibrutinib from 4 large phase 3 studies, the agent was associated with a low but continuous rate of arrhythmia. Although only 5.3% of patients experienced atrial fibrillation in the first 6 months, the cumulative incidence increased to 13.8% after 36 months of drug exposure.4 Idelalisib has been associated with rare but occasionally severe autoimmune-related colitis, pneumonitis, and risk of infections. Interim safety analyses of 3 phase 3 studies in patients with previously untreated CLL and indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma were halted because of excess deaths and serious AEs, including opportunistic infections, among patients in the groups treated with idelalisib.5 Perhaps not surprisingly, toxicity (not progression!) has become the most common reason for discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in clinical practice.6 Hence, as second-generation BTKi’s and PI3Ki’s entered into clinical studies, there was great hope that differing mechanisms of action and/or mode of delivery would result in greater tolerability with equal or even improved efficacy.

Umbralisib is an oral PI3Kδ inhibitor which also inhibits CK1ε. Unlike previous PI3Ki’s, it is not metabolized through the CYP pathway and has potentially higher selectivity for the δ isoform of PI3K, thought to be the primary drug target in CLL. Recently, a randomized phase 3 study of umbralisib plus ublituximab compared with obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in untreated and relapsed CLL was closed after an independent review panel determined that the umbralisib combination induced a statistically significant improvement in PFS (P < .0001).7

Mato et al report the results of one of the first studies to prospectively explore the ability to switch between KIs (either within or across classes) in patients who exhibited intolerance to a previous KI. The study enrolled 51 previously treated CLL patients (44 had previous exposure to BTKi’s and 7 had previous exposure to PI3Ki’s). At study entry, patients were given single-agent umbralisib until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Overall, the strategy seemed to be effective, with a median PFS of 23.5 months. Importantly, the median duration while receiving therapy was longer with umbralisib than with previous KIs. Although rare AEs such as pneumonitis and colitis were observed, only 8 patients (16%) had dose reductions and only 12% discontinued umbralisib because of toxicity. Although these findings suggest that umbralisib has a better tolerability profile than other KIs, true comparison is difficult without a head-to-head study.

The Mato et al study is the first to suggest that switching between KIs with different mechanisms of action is effective and safe in CLL. It also supports the growing understanding that until combination studies mature, the majority of emerging targeted agents in CLL will likely be used in series. Despite these encouraging results, several questions remain. What is the ideal roadmap for sequencing KIs or other targeted agents? Is dose or schedule reduction, interruption, or time-limited therapy an alternative to switching agents (especially in responding patients)?

As next-generation KIs with more tolerable toxicity profiles become broadly available, it is likely that more patients will receive effective therapy and remain on it longer. Several ongoing studies are also exploring innovative dosing schedules as well as time-limited therapy in patients who achieve minimal residual disease negativity. Until these studies are complete, preliminary evidence from real-world studies suggests that some patients can be successfully re-challenged after dose interruption or reduction without changing agents.5,6 Of course, the decision to resume dosing should be carefully considered and must weigh the severity and duration of previous toxicity against the magnitude of previous response and the immediate risk of CLL to the patient’s long term outcome (see figure). For patients in whom re-exposure is attempted, close multidisciplinary monitoring is recommended. Although these decisions currently represent a therapeutic challenge, they also exemplify the bright and dynamic future of CLL therapy, in which more and more clinicians will have the luxury of choice between several safe and effective options to improve the outcomes of CLL patients in their care.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.F. served on scientific advisory boards and received research funding from Gilead, TG Therapeutics, Janssen, Novartis, and Bristol Myers Squibb.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal