Key Points

ABCC4 encoding the multidrug resistance protein 4 specifies the novel PEL human blood group system.

The rare PEL-negative phenotype is associated with impaired platelet aggregation.

Abstract

The rare PEL-negative phenotype is one of the last blood groups with an unknown genetic basis. By combining whole-exome sequencing and comparative global proteomic investigations, we found a large deletion in the ABCC4/MRP4 gene encoding an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter in PEL-negative individuals. The loss of PEL expression on ABCC4-CRISPR-Cas9 K562 cells and its overexpression in ABCC4-transfected cells provided evidence that ABCC4 is the gene underlying the PEL blood group antigen. Although ABCC4 is an important cyclic nucleotide exporter, red blood cells from ABCC4null/PEL-negative individuals exhibited a normal guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate level, suggesting a compensatory mechanism by other erythroid ABC transporters. Interestingly, PEL-negative individuals showed an impaired platelet aggregation, confirming a role for ABCC4 in platelet function. Finally, we showed that loss-of-function mutations in the ABCC4 gene, associated with leukemia outcome, altered the expression of the PEL antigen. In addition to ABCC4 genotyping, PEL phenotyping could open a new way toward drug dose adjustment for leukemia treatment.

Introduction

Blood group phenotypes are defined by the presence or absence of specific antigens on the surface of the red blood cell (RBC) membrane and are inherited characteristics resulting from genetic polymorphism at the 38 currently identified blood group loci.1 Most blood group systems are carried by glycoproteins or glycolipids, with the antigen specificity determined by either an amino acid sequence or an oligosaccharide moiety (eg, ABO). The majority of blood antigen-carrying proteins have important functions not only in RBCs but also in other tissues. Hence, because of their polymorphisms and the existence of natural null phenotypes, blood groups also represent powerful tools to investigate human diseases.2-4 However, some null phenotypes are not accompanied by any evident pathologies, suggesting that some redundancy and compensatory mechanisms occur in individuals with the corresponding null phenotype.5,6 For example, some blood group antigens are carried by members of the ABC transporter family, and we have recently demonstrated that null alleles of ABCB6 and ABCG2 are responsible for the Lan- and Jr(a-) blood phenotypes, respectively.7,8 Despite the important physiological role of ABC transporters, individuals with both those phenotypes are apparently healthy.

Although the genetic loci of most blood group antigens have been identified, the genetic basis of some high-frequency blood group antigens remains unknown. In 1980, Daniels described a new high-frequency red cell antigen, provisionally called PEL after the proband’s name.9 Sixteen years later, it was shown that some other rare French-Canadian individuals made an antibody against a high-prevalence blood group antigen reacting with all RBCs tested except their own and other PEL-negative probands.9 Anti-PEL was never reported to cause hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. The clinical significance of this antibody in case of an incompatible transfusion is unknown; however, a reduced survival of transfused 51Cr-labeled incompatible red cells was observed.9 Family studies showed that the PEL-negative phenotype was inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, but the PEL locus remained undetermined until now.9

In this study, we demonstrated that the ABC transporter ABCC4 (also called MRP4 for multidrug resistance protein 4) carries the PEL antigen, and that a large deletion in the ABCC4 gene is responsible for the PEL-negative blood type. These findings elucidate the molecular basis of a new human blood group system. In agreement with the proposed role of ABCC4 in mouse models,10,11 we reported an impairment of platelet aggregation in 4 PEL-negative individuals.

Methods

Samples

Blood samples from previously characterized PEL-negative individuals were cryopreserved in the rare blood collection of Hema-Quebec and the National Reference Center for Blood Group (biocollection, DC-2016-2872). Informed consent was obtained for the PEL-negative subjects, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocols and approved by the Ethical Committee of Héma-Québec.

Antibodies

The anti-PEL was sourced from Mrs. “Pel,” described in 1980, and from “HugS” subject, both described in the original paper.9 By indirect antiglobulin testing at 37°C on papain-treated RBCs, HugS and Pel sera were found to react 3+ (titer 64, score 69) and 2+ (titer 2, score 12), respectively. Anti-PEL was purified after adsorption of human polyclonal anti-PEL from the serum sample of Mrs. “HugS”9 onto a pool of 3 group O papain‐treated RBCs at 37°C, followed by an acid elution test with the Gamma ELU‐KIT II device (Immucor). The PEL specificity of the eluate was verified, as well as the absence of contaminating ABO antibodies. This eluate was used to confirm the PEL-negative phenotype of all individuals from the 4 families previously described in the original manuscript.9 The investigation by flow cytometry of the antibody class and subclass of the eluate was consistent with a mix of immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2, with no IgG3, IgG4, or IgM. The monoclonal anti-ABCC4 antibody targeting N-terminal amino acids 1 to 110 of the ABCC4 protein was purchased from Abcam (ab56675; Abcam, Cambridge, MA).12,13

Whole-exome sequencing and data analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from leukocytes, using the MagnaPure system (Roche). Exome capture was performed with the Sure Select Human All Exon Kit (Agilent Technologies). A detailed protocol is provided in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site.

Sanger sequencing and PCR genotyping

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer pairs ABCC4-FWD1 (forward) and ABCC4-AS1 (reverse) were used to amplify the region containing the breakpoint between exon 20 and downstream of the 3′ untranslated region caused by a deletion in the ABCC4 gene. PCR products were purified with SureClean Plus (Bioline) and sequenced by ABI BigDye terminator chemistry (GATC Biotech) with the primer ABCC4-AS2 (primer sequences are available in supplemental Table 1). For PCR genotyping of PEL-negative samples, 2 PCRs were performed with specific forward primers, WT-F and BK-F, and a common reverse primer, BK-R (primer sequences are available in supplemental Table 2).

Plasmid construction

The coding sequence of ABCC4 cDNA was amplified, using a forward primer containing the NheI restriction site at the 5′ end and a reverse primer containing the XhoI restriction site at the 5′ end, from the pcDNA3-ABCC4 plasmid provided by Gabriele Jedlitschky. The ABCC4 sequence was verified (identical to NM_005845) and cloned as a NheI/XhoI fragment into the pCEP4 vector.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK 293 cells and K562 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/GlutaMAX I (Invitrogen) and Iscove modified Dulbecco medium/GlutaMAX/N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (25 mM), respectively, supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (Dutscher, Brumath, France) and 1× antibiotic‐antimycotic solution (Invitrogen) at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. HEK293 cells were first transfected with the pCEP4‐ABCC4 plasmid by nucleofection, using the Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V (Amaxa). Stable HEK293 transfectants were obtained after 10 days of selection with hygromycin B (0.15 mg/mL, Invitrogen).

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

RBC membranes (ghosts) were prepared from frozen blood samples that were previously washed in phosphate-buffered saline. Briefly, ghosts were obtained by hypotonic lysis of RBCs with 5P8 buffer (5 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 8.0 and 0.35 mM EDTA at pH 8.0 containing 1 mM PMSF), followed by 4 washes with the same buffer and then stripped by incubation with 10 mM NaOH (40 min at 4°C). Ghost proteins were solubilized in Laemmli buffer and then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was then blocked and incubated with a monoclonal antibody to ABCC4 (1:500; Abcam) for 120 minutes at RT. Anti-ABCC4 labeling was revealed with an anti-mouse IgG(H+L) horseradish-peroxidase-linked goat antibody (1:800; P.A.R.I. S Biotech) for 30 minutes at 21°C. The membrane was also probed with rabbit antiserum to p55, which was used as a loading control.

Immunoprecipitation of the PEL antigen

The immunoprecipitation of the PEL antigen was performed as described previously.14 Briefly, RBC ghosts from PEL-positive and PEL-negative subjects were lysed for 1 hour at 4°C with gentle shaking in Na2HPO4 5 mM, NaCl 150 mM at pH 8.0, Triton X-100 2% with a protease inhibitor cocktail. Supernatant and pellet were separated by centrifugation (15 000g for 15 minutes at 4°C). Supernatant was incubated overnight at 4°C with the anti-PEL eluate. Immune complexes were purified with UltraLink Immobilized Protein A/G (Pierce), and the immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted in Laemmli buffer at 90°C for 5 minutes, and analyzed by western blot as described earlier.

Disruption of ABCC4 in K562 by CRISPR/Cas9

Gene editing by CRISPR/Cas9 technology was performed as described previously.15,16 The pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro (PX459) expression vector was purchased from Addgene (plasmid #48139). Three guides were selected with CRISPRdirect (http://crispr.dbcls.jp/).17 Oligonucleotides (supplemental Table 3) were ligated into the BbsI linearized PX459 plasmid. The integrity of each cloned guide sequence was checked by Sanger sequencing with PX459 plasmid sequencing primer (supplemental Table 3). Five micrograms purified plasmid were electroporated with 106 K562 cells, using Nucleofector II and the V/program T-016 kit (Lonza). Cells were seeded at a density of 150 000 cells/mL 48 hours before electroporation. Viability was higher than 95% on the day of transfection. Transfected K-562 cells were grown with puromycin (5 μg/mL) in the culture medium 24 hours after transfection for 4 days. Then, the cells were grown without puromycin. The generation of indel events in the ABCC4 gene was assessed using T7 endonuclease I enzyme (New England Biolabs) 15 days after transfection.

Platelet aggregation studies

Platelet aggregation was measured with an optical platelet aggregometer (Chronolog model 490 4+4; Chrono-log Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro erythropoiesis

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from the peripheral blood samples of healthy donors, using a Ficoll density gradient separation (Pancoll 1.077 g/mL, PAN BIOTECH). CD34+ cells were then purified using anti-CD34 conjugated microbeads and manual cell separation columns (Miltenyi). The cell culture procedure was composed of 2 phases, as described by Freyssinier et al.18,19

Flow cytometric analysis of PEL and Jra antigen expression

Thawed RBCs or fresh cells (K562 and HEK293) were washed 3 times in phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco) and then resuspended in low-ionic strength buffer supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin and incubated with anti-PEL eluate (1:2) or mouse anti-ABCG2 (5D3, 1:20; Ozyme). Anti-PEL labeling was revealed with anti-human IgG-PE (1:50; Beckman Coulter), and anti-Jra (ABCG2) labeling was revealed with anti-mouse IgG-PE (1:100; Beckman Coulter). A FACSCantoII flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and FlowJo software were used for data acquisition and analysis, respectively.

Label-free quantification mass spectrometry analysis

Ghosts from 4 healthy donor control samples and 3 PEL individuals were obtained as described earlier and then lysed by heating for 5 minutes at 95°C in the same volume of 2× lysis buffer (100 mM Tris/HCl at pH 8.5, 2% SDS). Proteomic analyses were performed by using the label-free proteomic method. Raw data were analyzed by label-free quantification on MaxQuant software. A detailed protocol for this analysis is provided in supplemental Methods.

Intracellular cGMP measurements

The intraerythrocytic guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) level was measured as described previously.20 Briefly, packed and washed RBCs were lysed and then the intracellular cGMP was measured following the enzyme immunoassay procedure according to the instructions provided by the supplier (code RPN226; Kit Biotrak, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney test (GraphPad Prism V7).

Results

A large deletion in the ABCC4 gene causes the PEL-negative blood type

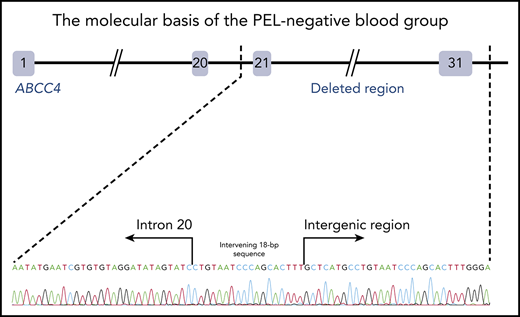

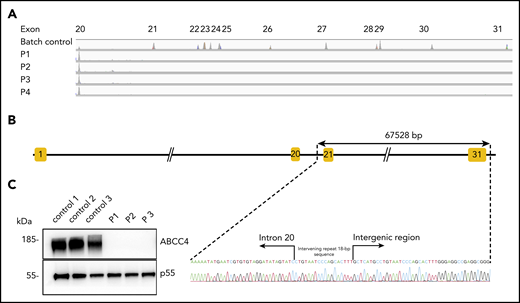

To identify the molecular basis of the PEL blood group, whole-exome sequencing was performed using genomic DNA from leukocytes of 1 French-Canadian PEL-negative individual in each of the 4 unrelated families described in the original paper.9 Variant filtering strategies failed to reveal any single mutations or indel variants common to the 4 PEL-negative individuals. We hypothesized that the PEL-negative phenotype could be a result of a deletion of 1 or several exons in a candidate gene encoding a red cell membrane protein. We then used a comparative global proteomic strategy to analyze the differential expression of membrane proteins in RBC membranes (ghosts) from 3 PEL-negative and 3 PEL-positive individuals as controls. Only 1 missing membrane protein was identified, ABCC4/MRP4, which was absent in the ghosts from all 3 PEL-negative samples compared with the control ghosts (supplemental Data File). We then verified the exon coverage in ABCC4 genes by analyzing copy number variation data. Integrative Genomics Viewer analysis revealed a large homozygous deletion in the ABCC4 gene (GenBank: NM_005845) in the 4 PEL-negative individuals (Figure 1A). The 67 528-bp deletion identified in the ABCC4 gene of PEL-negative samples removed the last 10 exons of the gene and part of the downstream 3′ untranslated region. Using a primer walking approach and Sanger sequencing, the precise breakpoints of the deletion were identified between intron 21 and the intergenic region, with coordinates from chromosome 13:95 018 454 to 95 085 982 (GRCh38/hg38 assembly; Figure 1B). This deletion was accompanied by the insertion of an intervening 18-bp sequence that corresponds to an intronic sequence repeated 62 times in the ABCC4 gene (Figure 1B). We next performed Sanger sequencing of the ABCC4 gene in 8 additional PEL-negative individuals from the 4 families. All these individuals were homozygous for the same deletion/insertion, although the family investigation showed no relationship over the last 5 generations.

The null allele of the ABCC4 gene is responsible for the PEL-negative phenotype. (A) Integrative Genomics Viewer analysis reveals homozygous loss of exons from 21 to 31 of the ABCC4 gene in 4 PEL-negative individuals (P1, P2, P3, and P4). (B) Schematic representation of the deletion in the ABCC4 gene and Sanger sequencing confirmation of the 67528-pb deletion/18-bp insertion in genomic DNA of PEL-negative individuals. (C) Western blot analyses of ABCC4 in the RBC membranes from PEL-positive (controls 1, 2, and 3) and PEL-negative (P1, P2, and P3) individuals. Immunoblotting was performed with a mouse monoclonal antibody directed against ABCC4. The p55 antibody was used as a loading control.

The null allele of the ABCC4 gene is responsible for the PEL-negative phenotype. (A) Integrative Genomics Viewer analysis reveals homozygous loss of exons from 21 to 31 of the ABCC4 gene in 4 PEL-negative individuals (P1, P2, P3, and P4). (B) Schematic representation of the deletion in the ABCC4 gene and Sanger sequencing confirmation of the 67528-pb deletion/18-bp insertion in genomic DNA of PEL-negative individuals. (C) Western blot analyses of ABCC4 in the RBC membranes from PEL-positive (controls 1, 2, and 3) and PEL-negative (P1, P2, and P3) individuals. Immunoblotting was performed with a mouse monoclonal antibody directed against ABCC4. The p55 antibody was used as a loading control.

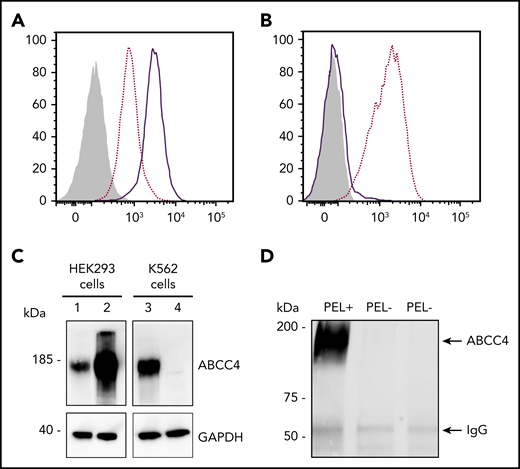

To validate the ABCC4 gene as the yet-unidentified genetic locus encoding the PEL antigen, we first performed western blot analysis using a monoclonal antibody specific for the first 110 amino acids of ABCC4. We showed that ABCC4 was present in the membrane of PEL-positive control RBCs, but totally absent in the PEL-negative RBCs (Figure 1C). According to the mass spectrometry data that failed to detect any ABCC4-derived peptide in the PEL-negative sample (supplemental Figure 1), no truncated protein was detected in these samples (supplemental Figure 1). These results strongly suggested that the large deletion in the ABCC4 gene may be responsible for the PEL-negative phenotype. To confirm that the ABCC4 protein carries the PEL antigen, we assessed whether exogenous ABCC4 expression in a transfected cell line would generate the expression of the PEL antigen. Flow cytometry analyses of HEK293 cells stably transfected with ABCC4 cDNA, using the anti-PEL eluate, revealed a significant increase of PEL antigen cell-surface expression (Figure 2A,C, left panel). To fully confirm the molecular basis of the PEL antigen, we generated 3 ABCC4-knockout K562 cell lines, using the CRISPR-Cas9 strategy with different RNA guides (gRNAs) targeting exons 8 and 18 of ABCC4 gene (supplemental Figure 1; Figure 2C, lane 4). Flow cytometry analysis using the anti-PEL eluate showed that the complete loss of ABCC4 abolished the expression of the PEL antigen in all 3 knockout cell lines (Figure 2B). Finally, the ABCC4 protein was immunoprecipated using anti-PEL eluate from RBC membrane extracts of PEL-positive subjects, but not from PEL-negative subjects (Figure 2D). All these genetic, molecular, and cellular data indicated that the PEL blood group is carried by the ABCC4 protein, and that homozygosity for a large deletion in the ABCC4 gene is responsible for the rare PEL-negative phenotype.

The ABCC4 transporter carries the PEL blood group antigen. (A) Cell surface expression of the PEL antigen in ABCC4-transfected HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells stably transfected with ABCC4 cDNA (thick lines) or an empty vector (dotted lines) were labeled with an anti-PEL and analyzed by flow cytometry. The gray profile corresponds to cells incubated with the secondary antibody only. (B) Surface level of PEL antigen on K562 cells transfected with plasmid allowing expression of Cas9 nuclease in combination with guide RNA-guide targeting exon 8 of ABCC4 (thick line) or Cas9 nuclease alone without guide RNA-guide (dotted lines). The gray profile corresponds to cells incubated with the secondary antibody only. (C) Western blot analysis of ABCC4 expression in HEK293 and K562 cells. Fifty micrograms of proteins from lysates of ABCC4-transfected (lane 2) or control (lane 1) HEK293 cells and ABCC4-knockout (lane 4) or control (lane 3) K562 cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and probed with a monoclonal anti-ABCC4 antibody. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. (D) Anti-PEL eluate is able to immunoprecipitate ABCC4 from RBC membrane extracts of PEL-positive subjects, but not from 2 PEL-negative subjects. Immune complexes were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions with heat denaturation, followed by western blot analyzes using the monoclonal anti-ABCC4.

The ABCC4 transporter carries the PEL blood group antigen. (A) Cell surface expression of the PEL antigen in ABCC4-transfected HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells stably transfected with ABCC4 cDNA (thick lines) or an empty vector (dotted lines) were labeled with an anti-PEL and analyzed by flow cytometry. The gray profile corresponds to cells incubated with the secondary antibody only. (B) Surface level of PEL antigen on K562 cells transfected with plasmid allowing expression of Cas9 nuclease in combination with guide RNA-guide targeting exon 8 of ABCC4 (thick line) or Cas9 nuclease alone without guide RNA-guide (dotted lines). The gray profile corresponds to cells incubated with the secondary antibody only. (C) Western blot analysis of ABCC4 expression in HEK293 and K562 cells. Fifty micrograms of proteins from lysates of ABCC4-transfected (lane 2) or control (lane 1) HEK293 cells and ABCC4-knockout (lane 4) or control (lane 3) K562 cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and probed with a monoclonal anti-ABCC4 antibody. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. (D) Anti-PEL eluate is able to immunoprecipitate ABCC4 from RBC membrane extracts of PEL-positive subjects, but not from 2 PEL-negative subjects. Immune complexes were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions with heat denaturation, followed by western blot analyzes using the monoclonal anti-ABCC4.

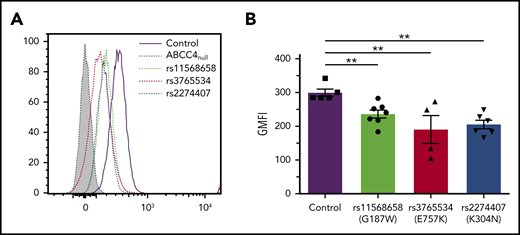

Effect of genetic variation in the ABCC4 gene on PEL antigen expression

The ABCC4 gene is highly polymorphic, and numerous nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms were associated with multiple disease susceptibilities.21,22 We investigated the effect of the major loss-of-function single-nucleotide polymorphisms rs11568658 (G187W), rs2274407 (K304N), and rs3765534 (E757K) on the PEL antigen expression at the red cell surface (Figure 3A). These heterozygous ABCC4 variants were selected from 85 whole exome-sequenced samples available from our own cryopreserved RBC bio-collection; all mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Flow cytometry analysis using anti-PEL eluate showed a moderate decreased expression of the PEL antigen in the G187W variant (16%), but a stronger decreased expression in the K304N and E757K variants (30% and 33%, respectively; Figure 3B). Interestingly, these latter variants have been shown to alter the membrane localization of ABCC4.23,24 These results indicated that a heterozygous mutation in the ABCC4 gene could affect the expression of the PEL antigen.

Impact of genetic variation in the ABCC4 gene on PEL expression levels. (A) Flow cytometry profiles of PEL expression in different red cell variants of ABCC4. (B) Corresponding geometric mean of fluorescence (GMFI) of PEL antigen expression in different variants of ABCC4. PEL expression was analyzed using an anti-PEL eluate. Heterozygous variants in ABCC4 were selected from our own RBC bio-collection. All mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Statistical analyses for significance were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. **P < .005.

Impact of genetic variation in the ABCC4 gene on PEL expression levels. (A) Flow cytometry profiles of PEL expression in different red cell variants of ABCC4. (B) Corresponding geometric mean of fluorescence (GMFI) of PEL antigen expression in different variants of ABCC4. PEL expression was analyzed using an anti-PEL eluate. Heterozygous variants in ABCC4 were selected from our own RBC bio-collection. All mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Statistical analyses for significance were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. **P < .005.

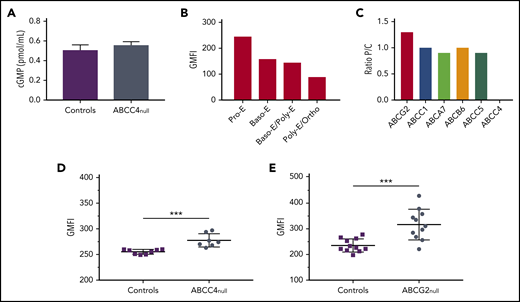

Role of ABCC4 in erythroid cells

To better understand the function of ABCC4 in mature erythroid cells, we measured the intracellular cGMP level in frozen stored RBCs from 5 PEL-negative individuals and 5 control individuals. We showed that the cGMP level was not significantly impaired in the absence of ABCC4 (Figure 4A), which is consistent with the absence of erythroid defects in these patients (supplemental Table 4). We then monitored the expression profile of ABCC4 during in vitro erythropoiesis (supplemental Figure 4). Figure 4B showed a higher expression level of ABCC4 in immature erythroblasts (pro-erythroblast stage), followed by a gradual decrease on erythroid terminal differentiation, suggesting a potential role for this transporter in cyclic nucleotide regulation in early erythroblasts. This finding raised the hypothesis that another cGMP transporter could compensate for the absence of ABCC4 on the membrane of mature RBCs. Previous studies using murine models reported that the absence of an ABC transporter can elicit compensatory changes in functionally related ABC transporters.25,26 Therefore, we reanalyzed our proteomic data to compare the expression of different ABC transporters at the RBC membrane from PEL-negative individuals (P) and control individuals (C). We found that 5 other ABC transporters (ABCC1, ABCA7, ABCB6, ABCC5, and ABCG2) were expressed on the surface of RBC membranes, and we calculated the P/C (proband/control) expression ratio for each of them. ABCC1, ABCA7, ABCB6, and ABCC5 exhibited a P/C ratio near 1, whereas ABCG2 expression was found to be increased by 1.3-fold in PEL-negative/ABCC4null RBCs (n = 3) compared with in control individuals (Figure 4C). ABCG2 overexpression in PEL-negative RBCs was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis, using an anti-ABCG2 antibody. Although ABCG2 expression was variable among PEL-negative RBCs (n = 7), it was significantly higher in this group than in control individuals (P = .0002; Figure 4D). These results suggested that the absence of ABCC4 in PEL-negative individuals could be compensated for by the overexpression of ABCG2. We have recently shown that ABCG2 is the carrier of the JR blood group system, and that the rare Jr(a-) (ABCG2null) individuals did not exhibit any specific apparent clinical features.8 To confirm our hypothesis, we analyzed ABCC4 expression in RBCs from ABCG2null individuals (n = 11) and controls by flow cytometry (n = 11). Figure 4E showed a significant upregulation of ABCC4 expression in the absence of ABCG2 (P = .0007). Our data, together with previous studies indicating that both ABCC4 and ABCG2 export cGMP,27 suggest that the overexpression of ABCG2 in PEL-negative RBCs may represent a compensatory mechanism for the lack of ABCC4, which could explain the absence of erythroid disorder in PEL-negative individuals (supplemental Table 4). To confirm that the upregulation of ABCG2 in these patients is actually a result of the absence of ABCC4, we analyzed the expression of ABCG2 in the previous loss-of-function variants of ABCC4 (K304N, E757K, and G187W). We did not find any increase in the ABCG2 expression in these variants (data not shown), suggesting that the upregulation of ABCG2 in ABCC4null RBCs could be specific for PEL-negative families.

Role of ABCC4 in erythroid cell. (A) cGMP levels in RBCs from control (n = 7) and PEL-negative (n = 7) individuals. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. (B) ABCC4 expression during terminal erythroid differentiation. Erythropoiesis was monitored via CD49d and band3 levels of GPApos cells and May-Grunwald Giemsa-staining. The ABCC4 expression was determined on the GPApos cells, using the anti-PEL eluate. (C) P/C ratios for ABC transporter expression in RBC membranes from 3 PEL-negative ABCC4 null individuals (P) and 3 control individuals (C). The P/C ratio was determined after normalization of the LFQ intensity of ABC transporter proteins by the LFQ intensity of actin. (D) The GMFI of ABCG2 expression in ABCC4null (n = 7) and control (n = 8) RBCs was analyzed by flow cytometry, using an anti-ABCG2 antibody. ***P = .0002, using the Mann-Whitney test. (E) The GMFI of ABCC4 expression in ABCG2null (n = 11) and control (n = 11) RBCs was analyzed by flow cytometry, using an anti-PEL. ***P=.0007, using the Mann-Whitney test.

Role of ABCC4 in erythroid cell. (A) cGMP levels in RBCs from control (n = 7) and PEL-negative (n = 7) individuals. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. (B) ABCC4 expression during terminal erythroid differentiation. Erythropoiesis was monitored via CD49d and band3 levels of GPApos cells and May-Grunwald Giemsa-staining. The ABCC4 expression was determined on the GPApos cells, using the anti-PEL eluate. (C) P/C ratios for ABC transporter expression in RBC membranes from 3 PEL-negative ABCC4 null individuals (P) and 3 control individuals (C). The P/C ratio was determined after normalization of the LFQ intensity of ABC transporter proteins by the LFQ intensity of actin. (D) The GMFI of ABCG2 expression in ABCC4null (n = 7) and control (n = 8) RBCs was analyzed by flow cytometry, using an anti-ABCG2 antibody. ***P = .0002, using the Mann-Whitney test. (E) The GMFI of ABCC4 expression in ABCG2null (n = 11) and control (n = 11) RBCs was analyzed by flow cytometry, using an anti-PEL. ***P=.0007, using the Mann-Whitney test.

Loss of ABCC4 results in impaired platelet aggregation in PEL-negative individuals

ABCC4 is highly expressed in platelets and was initially suggested as the ADP transporter in dense granules.28 Two recent studies using ABCC4-knockout mice indicated a role for ABCC4 in platelet aggregation and involvement in cAMP, rather than ADP transport.10,11 In addition, 1 of those studies localized ABCC4 to the plasma membrane by structured illumination microscopy and biochemical approaches. Because anti-PEL represents the only currently available probe to detect ABCC4 at the cell surface, we used it in flow cytometry and showed that this protein is expressed at the plasma membrane of platelets from control individuals, but not from PEL-negative individuals (supplemental Figure 5). We then investigated platelet function in 4 PEL-negative individuals. These individuals showed similar complete blood count parameters compared with reference values, with a platelet count within the normal range, and with no signs of easy bruising or increased bleeding tendency (supplemental Table 4). We then assessed platelet aggregation test in the 4 PEL-negative individuals. No difference was noted in platelet aggregation induced by collagen (80% ± 4.9% at 2 µg/mL; normal range, 70%-94%) and by a high ADP concentration (67% ± 14% at 10 µM; normal range, 71%-88%). Conversely, at lower ADP concentrations of 2.5 and 5 µM, platelet aggregation was decreased in the PEL-negative individuals (9.5% ± 4.9% and 27% ± 11%, respectively) compared with reference ranges (75%-95% and 78%-91%, respectively).29 These findings suggest a potential role of ABCC4 in platelet aggregation.

Discussion

Since the initial description of the PEL antigen, and despite efforts that have been made toward finding its molecular basis, the elucidation of the PEL blood group system has remained an enigma for almost 40 years. Here, we combined multiple omics approaches to demonstrate that a large deletion in the ABCC4 gene is responsible for the PEL-negative blood type, and we provided evidence that ABCC4 underlies the PEL blood group antigen. Thus, these findings elevate PEL to a novel blood group system to be joined to the 38 currently known systems. The discovery of a novel human blood group system is an exceptional event, representing a milestone in transfusion medicine and in genetic fields. As an example, the recent characterization of the molecular basis of the VEL antigen and the rare Vel-negative blood type, particularly found in Northern Scandinavia, allowed to set up a genotyping program at the Regional Blood Center in Lund, Sweden.30 Interestingly, as the PEL-negative blood type has been found only in the French-Canadian population, a mass-screening genotyping program in Canada, especially in the Quebec province, would probably make it possible to identify other ABCC4 null individuals. This could add value to estimate the prevalence of this rare blood type, as well as to help in the search for compatible blood for patients potentially immunized against the PEL antigen. The identification of the ABCC4 deletion breakpoint in PEL-negative individuals allowed us to develop a PCR genotyping assay (supplemental Figure 6).

The multidrug resistance protein ABCC4/MRP4 belongs to the ATP-binding cassette family of membrane transporters, and is expressed in blood cells as well as in several tissues, including the kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, and prostate, and particularly in blood cells. PEL-negative individuals are the first-ever-reported people lacking the complete expression of the ABCC4 protein. Surprisingly, despite the expected biological importance of ABCC4 as a cyclic nucleotide transporter, no apparent mutual symptoms or diseases were identified after investigation of the clinical history of the 12 PEL-negative members within the 4 families analyzed in this study. Although the intracellular cyclic nucleotides is crucial for the proliferation and differentiation of early erythroblasts and for hemoglobin synthesis,31,32 no erythroid disorders were reported in the PEL-negative individuals. The overexpression of ABCG2 in the mature PEL-negative RBCs and its involvement in a potential compensatory mechanism need to be confirmed in erythroid precursors of PEL-negative individuals.

ABCC4 regulates the cellular efflux of cGMP and cAMP involved in cellular signaling and, more recently, in platelet activation.10,11,28,33 In vitro platelet aggregation test performed in 4 ABCC4null/PEL-negative blood samples suggests an impaired platelet aggregation at low ADP concentration because of the absence of ABCC4. These results are in total accordance with previous studies showing that the inhibition of ABCC4 leads to a decrease in human platelet function, and that an inhibitor of ABCC4 (MK 571) can be used as a therapeutic molecule to potentiate the aggregating effects of some guanylate cyclase activators usually used in thrombotic complications.34 The role of ABCC4 in platelet function has also been demonstrated in ABCC4-deficient mice in which the cytosolic level of cAMP in platelets is higher than in wild-type mice.10,11

In malignant diseases, ABC transporters contribute to chemotherapy resistance because of their drug efflux capabilities in cancer cells.35 The overexpression of ABC transporters represents a powerful prognostic marker in acute myeloid leukemia.36-38 An exciting hypothesis would be that the expression of these transporters on red cells, an easily available biological material through a simple peripheral blood sample, could reflect their overexpression in other blood cells. Because ABCC4 (carrying the PEL antigen) can now be considered the third ABC transporter coding for a human blood group system, after ABCB6 (carrying the Lan antigen) and ABCG2 (carrying the Jra antigen),7,8 a pilot study is required to determine whether red blood cell typing may help to predict poor or good prognosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. In contrast, ABCC4 exports a wide variety of drugs and confers resistance to thiopurines, such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and thiopurines (eg, 6-thioguanine and 6-mercaptopurine). ABCC4 is strongly expressed in hematopoietic cells, and some variants of this gene are associated with a higher toxicity of methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine anticancer drugs, which have an effect on the clinical outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia.22,39-42 Notably, the loss-of-function ABCC4 variant p.Glu757Lys (rs3765534) known to impair the membrane localization of ABCC4 is frequently present in the Japanese population (minor allele frequency, 18%) where it is associated with severe leukopenia in pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with the 6-mercaptopurine drug.24,43 Consistently, our results showed that this variant alters the expression of the PEL antigen at the red cell surface. As genotyping of ABCC4 is strongly recommended before thiopurine administration in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia,43 it could also be interesting to propose a PEL phenotyping for optimal drug dose adjustment and prevention of chemotherapy adverse effects.

In conclusion, we characterized the molecular basis of the novel human blood group system PEL and demonstrated that a null allele of ABCC4 specifies the PEL-negative phenotype by an innovative approach combining whole-exome sequencing and global comparative proteomic analysis. The elucidation of this novel blood group system should prove high clinical interest, both in transfusion medicine and in chemotherapy treatment.

For original proteomic data, please contact patrick.mayeux@inserm.fr

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Salem Achour for his help with cell culture and cytometry experiments. They are indebted to Olivier Bertrand for helpful comments and for reading the manuscript. The authors also are grateful to André Lebrun, Marie-Claire Chevrier, Renée Bazin, and Gilbert Rodrigue for their assistance at Héma-Québec in this research project. They are thankful to Philippe Ohlmann and Anne Long for helpful discussion and advice.

This work was supported by a grant from l’Association Recherche et Transfusion (#151/2016), the Institut National de la Transfusion Sanguine, and the Laboratory of Excellence GR-Ex, reference ANR-11-LABX-0051; GR-Ex is funded by the program “Investissements d’avenir” of the French National Research Agency, reference ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02. The Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer was acquired with funds from the Fonds Européen de Développement Régional through the “Operational Programme for Competitiveness and Employment 2007-2013” and from the “Canceropole Ile de France."

This PEL blood group research study is dedicated to the memory of Corinne Nadeau Larochelle, 1988-2018.

Authorship

Contribution: S.A., Y.C., J.-P.C., C.L.V.K., and T.P. conceived the project; S.A., Y.C., C.L.V.K., and T.P. wrote the paper; S.A., O.H., C.L.V.K., and T.P. designed the research study; S.A., M.M., P.H., C.V., and A.R. performed the experiments; S.A., Y.C., C.L.V.K., and T.P. analyzed the data; A.W. and G.N. designed and performed the CRISPR Cas-9 experiments; E.-F.G., V.S., and P.M. realized the mass spectrometry and proteomic analyses; C.B.‐F. coordinated the whole-exome sequencing procedure; P.N. gave bioinformatics support; G.J., M.C., J.C.-Y., C.E., N.R., and M.S.-L. contributed essential material; and J.C.-Y. and M.S.-L. collected the clinical history of PEL-negative individuals.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Slim Azouzi, UMR_S1134/Institut National de la Transfusion Sanguine, 6 Rue Alexandre Cabanel, 75015 Paris, France; e-mail: slim.azouzi@inserm.fr; and Thierry Peyrard, UMR_S1134/Institut National de la Transfusion Sanguine, 6 Rue Alexandre Cabanel, 75015 Paris, France; e-mail: tpeyrard@ints.fr.

REFERENCES

Author notes

S.A. and M.M. contributed equally to this work.

C.L.V.K. and T.P. contributed equally to this work.