Human beta-like globin gene expression is developmentally regulated. Erythroblasts (EBs) derived from fetal tissues, such as umbilical cord blood (CB), primarily express gamma globin mRNA (HBG) and HbF, while EBs derived from adult tissues, such as bone marrow (BM), predominantly express beta globin mRNA (HBB) and adult hemoglobin. Human genetics has validated de-repression of HBG in adult EBs as a powerful therapeutic paradigm in diseases involving defective HBB, such as sickle cell anemia. To identify novel factors involved in the switch from HBG to HBB expression, and to better understand the global regulatory networks driving the fetal and adult cell states, we performed transcriptome profiling (RNA-seq) and chromatin accessibility profiling (ATAC-seq) on sorted EB cell populations from CB or BM. This approach improves upon previous studies that used unsorted cells (Huang J, Dev Cell 2016) or that did not measure chromatin accessibility (Yan H, Am J Hematol 2018).

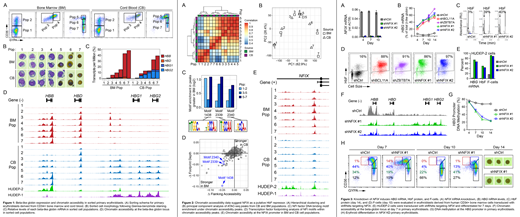

CD34+ cells from CB and BM were differentiated using a 3-phase in vitro culture system (Giarratana M, Blood 2011). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting and the cell surface markers CD36 and GYPA were used to isolate 7 discrete populations, with each sorting gate representing increasingly mature, stage-matched EBs from CB or BM (Fig 1A, B). RNA-seq analysis revealed expected expression patterns of the beta-like globins, with total levels increasing during erythroid maturation and primarily composed of HBB or HBG transcripts in BM or CB, respectively (Fig 1C). Erythroid maturation led to progressive increases in chromatin accessibility at the HBB promoter in BM populations. In CB-derived cells, erythroid maturation led to progressive increases in chromatin accessibility at the HBG promoters through the CD36+GYPA+ stage (Pops 1-5). Chromatin accessibility shifted from the HBG promoters to the HBB promoter during the final stages of differentiation (Pops 6-7), suggesting that HBG gene activation is transient in CB EBs (Fig 1D).

Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis of ATAC-seq data revealed that cell populations cluster based on differentiation stage rather than by BM or CB lineage, suggesting most molecular changes are stage-specific, not lineage-specific (Fig 2A, B). To identify transcription factors driving cell state, and potentially beta-like globin expression preference, we searched for DNA binding motifs within regions of differential chromatin accessibility and found NFI factor motifs enriched under peaks that were larger in BM relative to CB (Fig 2C). Transcription factor footprinting analysis showed that both flanking accessibility and footprint depth at NFI motifs were also increased in BM relative to CB (Fig 2D). Increased chromatin accessibility was observed at the NFIX promoter in BM relative to CB populations, and in HUDEP-2 relative to HUDEP-1 cell lines (Fig 2E). Furthermore, accessibility at the NFIX promoter correlated with elevated NFIX mRNA in BM and HUDEP-2 relative to CB and HUDEP-1, respectively. Together these data implicated NFIX in HbF repression, a finding consistent with previous genome-wide association and DNA methylation studies that suggested a possible role for NFIX in regulating beta-like globin gene expression (Fabrice D, Nat Genet 2016; Lessard S, Genome Med 2015).

To directly test the hypothesis that NFIX represses HbF, short hairpin RNAs were used to knockdown (KD) NFIX in primary erythroblasts derived from human CD34+ BM cells (Fig 3A). NFIX KD led to a time-dependent induction of HBG mRNA, HbF, and F-cells comparable to KD of the known HbF repressor BCL11A (Fig 3B-D). A similar effect on HbF was observed in HUDEP-2 cells following NFIX KD (Fig 3E). Consistent with HbF induction, NFIX KD also increased chromatin accessibility and decreased DNA methylation at the HBG promoters in primary EBs (Fig 3F, G). NFIX KD led to a delay in erythroid differentiation as measured by CD36 and GYPA expression (Fig 3H). Despite this delay, by day 14 a high proportion of fully enucleated erythroblasts was observed, suggesting NFIX KD cells are capable of terminal differentiation (Fig 3H). Collectively, these data have enabled identification and validation of NFIX as a novel repressor of HbF, a finding that enhances the understanding of beta-like globin gene regulation and has potential implications in the development of therapeutics for sickle cell disease.

Chaand:Syros Pharmaceuticals: Employment, Equity Ownership. Fiore:Syros Pharmaceuticals: Employment, Equity Ownership. Johnston:Syros Pharmaceuticals: Employment, Equity Ownership. Moon:Syros Pharmaceuticals: Employment, Equity Ownership. Carulli:Syros Pharmaceuticals: Employment, Equity Ownership. Shearstone:Syros Pharmaceuticals: Employment, Equity Ownership.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal