Abstract

Blood transfusion is the most common procedure completed during a given hospitalization in the United States. Although often life-saving, transfusions are not risk-free. One sequela that occurs in a subset of red blood cell (RBC) transfusion recipients is the development of alloantibodies. It is estimated that only 30% of induced RBC alloantibodies are detected, given alloantibody induction and evanescence patterns, missed opportunities for alloantibody detection, and record fragmentation. Alloantibodies may be clinically significant in future transfusion scenarios, potentially resulting in acute or delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions or in difficulty locating compatible RBC units for future transfusion. Alloantibodies can also be clinically significant in future pregnancies, potentially resulting in hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. A better understanding of factors that impact RBC alloantibody formation may allow general or targeted preventative strategies to be developed. Animal and human studies suggest that blood donor, blood product, and transfusion recipient variables potentially influence which transfusion recipients will become alloimmunized, with genetic as well as innate/adaptive immune factors also playing a role. At present, judicious transfusion of RBCs is the primary strategy invoked in alloimmunization prevention. Other mitigation strategies include matching RBC antigens of blood donors to those of transfusion recipients or providing immunomodulatory therapies prior to blood product exposure in select recipients with a history of life-threatening alloimmunization. Multidisciplinary collaborations between providers with expertise in transfusion medicine, hematology, oncology, transplantation, obstetrics, and immunology, among other areas, are needed to better understand RBC alloimmunization and refine preventative strategies.

Introduction

Over 11 million red blood cells (RBCs) are transfused annually in the United States, making transfusion the most common procedure completed during a given hospitalization.1,2 Transfusion threshold studies have shown that restrictive hemoglobin thresholds are as safe as or safer than liberal hemoglobin thresholds for many patient populations and indications, leading to a decline in transfused RBC units over the past decade.3 Despite decreasing transfusion burdens, however, alloantibody formation to transfused blood products remains a clinically significant problem. This review will focus on alloimmunization to non-ABO blood group antigens, also known as RBC antigens.

As discussed in more detail in this review, RBC alloantibodies may be clinically significant in future transfusion or pregnancy scenarios. These antibodies can lead to acute or delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions or hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. They may also lead to lengthy and costly evaluations in the blood bank and delays in locating compatible RBC units for future transfusions. Only a fraction of RBC alloantibodies formed are identified, given RBC alloantibody induction and evanescence kinetics in combination with other variables discussed in this paper. As such, the morbidity and mortality burden of RBC alloimmunization is likely underestimated.

RBC antigen characteristics

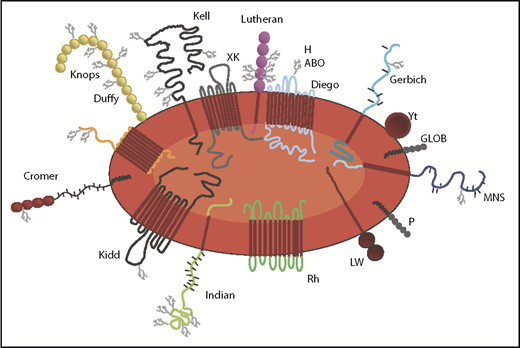

RBC antigens are numerous and diverse from a structural and functional perspective (Figure 1). Some antigens are proteins, while others are carbohydrates,4 and it is possible that the variables discussed throughout this paper may impact certain antigens differently than others. For instance, it has generally been found that polypeptide antigens give rise to alloantibodies of an immunoglobulin G (IgG) class (reactive at 37°C), while carbohydrate antigens tend to give rise to IgM-class antibodies showing strongest reactivity at 22°C (also referred to as immediate spin reactivity).5 Moreover, some antigens are expressed at high density, and some antigens show “dosage” with more antigen present in the homozygous state than the heterozygous state. Animal studies suggest that RBC antigens with extremely high density (such as KELhi)6 may be less immunogenic than antigens with a more moderate density, and animal and human studies suggest that antigens with extremely low densities (such as KELlo or weak RhD) have relatively low levels of immunogenicity.7,8 Antigens can be expressed solely on RBCs or expressed also on white blood cells (WBCs) or tissue. Some antigens are expressed very early in RBC development, whereas others are expressed later. The majority of clinically significant antigens reflect single amino acid polymorphism differences between donors and recipients (eg, K1/K2), while other important antigens (eg, RhD) reflect multiple amino acid differences and may be present in donors and lacking altogether in recipients (or vice versa). Moreover, antigens encoded by RHD and RHCE have complex variants9,10 discussed later in this review, that are more likely to be observed in individuals of African than European descent. The scientific community’s understanding of RBC antigens has increased considerably over the past decade with the introduction of high-throughput genotyping platforms and emerging next-generation sequencing studies.11 These advances have impacted blood donor centers, hospital transfusion medicine services, and obstetrical practices.

Cartoon of an RBC with representative blood group antigens. Drawn by Elisabet Sjӧberg Webster, and reproduced with permission. GLOB, globoside.

Cartoon of an RBC with representative blood group antigens. Drawn by Elisabet Sjӧberg Webster, and reproduced with permission. GLOB, globoside.

RBC alloantibody formation, detection, and evanescence

Although there are hundreds of non-self RBC antigens in every transfused RBC unit, only a minority of transfusion recipients will ever develop detectable RBC alloantibodies. For an alloantibody to develop an individual must, at a minimum, (1) be exposed to a non-self RBC antigen and (2) have an HLA-binding motif capable of presenting a portion of the non-self antigen. There are multiple different HLA types capable of presenting portions of studied RBC antigens.12-19 HLA restriction for studied RBC antigens is not limited like it is for the human platelet glycoprotein antigen 1a (HPA1a), which is highly associated with HLA class II DRB3*01:01.20

There are additional factors to take into consideration in determining which transfused recipients may form RBC alloantibodies, though, since essentially all transfused RBC units have non-self antigens and essentially all transfused recipients have HLA-binding motifs capable of presenting some portion of some of these antigens. It has been estimated, for example, that >99% of transfused individuals should be capable of making at least 2 RBC alloantibodies based on donor/recipient RBC antigen mismatches and general RBC antigen prevalence rates. The percentage of alloimmunized patients increases up to a certain point with transfusion burden but plateaus once a given individual has been exposed to most “non-self” blood group antigens. Despite this capability, however, retrospective studies document that only 2% to 5% of general transfused individuals develop detectable RBC alloantibodies.5 This alloimmunization prevalence must be considered with the perspective of the 11 million RBC units transfused annually. Prospective studies document higher levels of RBC alloimmunization, as do studies of patient populations or inflammatory conditions surrounding a transfusion (described in more detail later in this review).

Alloantibodies to RBC antigens are detected by the “screen” portion of the type and screen. This screen, also known as an indirect antiglobulin or indirect Coombs test, is aimed at detecting common, clinically significant RBC alloantibodies. The antibody screen typically involves testing the patient’s plasma against reagent RBCs with known antigen specificities21 and, in the United States, is often completed using a solid-phase or gel card platform. Single antibodies, such as anti-D or anti-K, may be easily identified using these assays. The identification of multiple alloantibodies becomes more complex and time-consuming, as there are currently no “single bead/single antigen” tests available for RBC alloantibody detection like there are for HLA antibody detection due to the structural complexity and diversity of RBC antigens. Further, using current blood-banking methodology, antibodies that are low titer may not be detected, yet antibodies of undetermined significance may be identified.22 The detection antibody used in the screen is anti-human IgG,21 and antibodies of different classes or of certain subtypes23 may require specialized reference laboratory testing for identification.

Following alloantibody identification, a crossmatch, which serves as a final check of compatibility, then mixes the patient’s plasma with the antigen-negative donor RBCs to be transfused. Alloantibodies against low-incidence antigens may first be detected during the crossmatch if the low-incidence antigen was not present on reagent screening cells. Additional testing may be completed by transfusion services for pregnant alloimmunized women, including serial RBC alloantibody titers. Further testing, including functional antibody analysis by chemiluminescence or monocyte monolayer assay,24,25 may be completed in some countries to predict the clinical significance of detected alloantibodies. Research studies have also shown RBC alloantibody glycosylation patterns to be associated with clinical significance in some settings.26,27

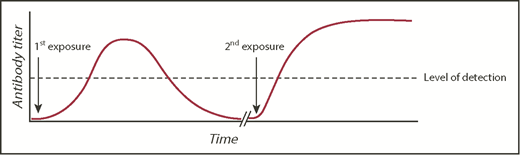

Obtaining a prior transfusion history from patients is critical for optimal transfusion safety. In the United States, there is no nationwide antibody registry. Thus, a patient may be transfused at one hospital and have a RBC alloantibody detected but subsequently receive care at another hospital that has no knowledge of the antibody, resulting in the phenomenon known as transfusion record fragmentation.28 If the antibody detected at the first hospital has evanesced29 or fallen below the level of detection by traditional blood banking methodology by the time the patient is seen at the second hospital, then a seemingly compatible RBC transfusion could result in a rapid anamnestic RBC alloantibody response (Figure 2). Such a response may lead to a delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction (DHTR), in which an anamnestic antibody response leads to hemolysis and premature clearance of the transfused RBCs, or a delayed serologic transfusion reaction, in which an anamnestic antibody is identified by the transfusion service but may not cause hemolysis.30

RBC alloantibody induction, evanescence, and anamnestic response. A model figure of events leading to a DHTR, with the typical time course of primary alloimmunization, antibody evanescence, and anamnestic response. The dashed line represents an example threshold of antibody detection by a transfusion service.

RBC alloantibody induction, evanescence, and anamnestic response. A model figure of events leading to a DHTR, with the typical time course of primary alloimmunization, antibody evanescence, and anamnestic response. The dashed line represents an example threshold of antibody detection by a transfusion service.

There are other factors that also play into risks for DHTRs and transfusion incompatibilities. Because of the importance in contributing to alloantibody-associated adverse events, the disappearance of RBC alloantibodies below the level of detection warrants further discussion. Efforts to quantitate antibody evanescence have largely focused on 2 subsets of patient groups, including hospitalized patients with any diagnosis and those with sickle cell disease (SCD). Such studies have clearly indicated that evanescence is not a phenomenon limited to alloimmunization to a single antigen or group of antigens but is instead a phenomenon that affects many different alloantibodies across antigenic specificities.31,32 As shown in Table 1, some of the highest evanescence rates have been reported for alloantibodies to antigens in the Kidd (Jka and Jkb), Lutheran (Lua), and Kell systems (Jsa), while select antigens within the Rh system (specifically D and c) tend to be associated with more durable humoral responses.

Mean evanescence rates by RBC alloantibody specificity

| Blood group system . | General patient groups (%)* . | Sickle cell disease groups (%)* . |

|---|---|---|

| Duffy | ||

| Fya | 17 | 51 |

| Fyb | — | 78 |

| Kell | ||

| K | 32 | 41 |

| Jsa | — | 80 |

| Kidd | ||

| Jka | 49 | — |

| Jkb | 54 | 58 |

| Lewis | ||

| Lea | 48 | — |

| Leb | 52 | — |

| Lutheran | ||

| Lua | 65 | — |

| MNS | ||

| M | 30 | 38 |

| S | 30 | 66 |

| P | ||

| P1 | 50 | — |

| Rh | ||

| D | 12 | 36 |

| C | 19 | 47 |

| c | 27 | 0 |

| E | 38 | 41 |

| Cw | 61 | — |

| V | — | 39 |

| Blood group system . | General patient groups (%)* . | Sickle cell disease groups (%)* . |

|---|---|---|

| Duffy | ||

| Fya | 17 | 51 |

| Fyb | — | 78 |

| Kell | ||

| K | 32 | 41 |

| Jsa | — | 80 |

| Kidd | ||

| Jka | 49 | — |

| Jkb | 54 | 58 |

| Lewis | ||

| Lea | 48 | — |

| Leb | 52 | — |

| Lutheran | ||

| Lua | 65 | — |

| MNS | ||

| M | 30 | 38 |

| S | 30 | 66 |

| P | ||

| P1 | 50 | — |

| Rh | ||

| D | 12 | 36 |

| C | 19 | 47 |

| c | 27 | 0 |

| E | 38 | 41 |

| Cw | 61 | — |

| V | — | 39 |

Data were extracted and aggregated from previously published studies, with evanescent antibodies of each specificity available totaled and divided by the overall number of antibodies of that specificity identified. To be included in the above analysis, the overall number of antibodies of a given specificity had to tally ≥5. Dashes indicate that too few antibodies of a given specificity were available for inclusion in the analysis.

The immunologic processes underlying evanescence remain poorly understood, and it is unclear why some RBC alloantibody responses are more durable than others. Persistent alloantibody detection could reflect the immune response to structural differences between antigens (ie, antigenic “foreignness”) to the host. This may also reflect the fact that there are multiple potential targets for an antibody response to certain antigens (eg, RhD), whereas there may be only a single target for other antigens that reflect single amino acid substitutions between donor and recipient.

In addition to the substantial rates of disappearance seen across various antibody specificities, it is also important to note that these alloantibodies can disappear very rapidly after their initial induction. Retrospective reports have shown that approximately one-quarter of induced alloantibodies can disappear from detection within 1 month of their initial discovery, with half undetectable at 6 months after detection. Overall, when evanescent specificities are combined, rates of disappearance approach 60% to 70% of total induced alloantibodies at a period of 5 years after initial detection.29,31,33

Based on the kinetics of alloantibody induction and the rapid disappearance rate of large swaths of blood group alloantibodies as described above, a recent retrospective study revealed the relatively low yield of the nonsystematic, essentially random nature with which antibody screen testing is performed posttransfusion.31 When these factors are combined with the observation that many patients never undergo a follow-up antibody screen, it has been estimated that only ∼30% of induced alloantibodies are regularly detected by antibody screen methods. Thus, transfusion record fragmentation, antibody evanescence, and low antibody detection rates posttransfusion are all major obstacles in identifying and documenting blood group alloantibodies and all are significant contributors to risks for DHTRs.

There are many ongoing initiatives, as well as future goals, of the transfusion medicine community to help overcome these myriad issues of antibody detectability. Regarding the problem of record fragmentation, the establishment of local, regional, or even national antibody registries would greatly impact the portability of alloimmunization data. While such registries are available globally, there are only limited reports of such networks from within the United States. A promising study originating from the Kansas City region indicated that a shared registry in that locale prevented multiple delayed reactions.34 Since that publication, there has been little progress in the establishment of other, similar registries across the United States. In addition to simply sharing information, it is also imperative that our understanding of the mechanisms of evanescence be improved. At present, for example, it is not possible to predict which patients will undergo antibody evanescence, nor is there any understanding of how quickly this may occur. It is also not known whether antibody persistence depends on the nature of the sensitizing event (eg, transfusion vs pregnancy). One simple solution to the problem of missing alloimmunization events is to implement a more rigorous approach to follow-up testing after RBC transfusion,35 especially in patients at highest risk for RBC alloimmunization.

Clinical significance of RBC alloimmunization

Alloimmunization is a cause of transfusion-associated mortality, although such mortality resulting directly from alloimmunization is relatively rare.1 More common transfusion associated complications from RBC alloimmunization include (1) transfusion delays as new alloantibodies are in the process of being identified, (2) difficulties in locating compatible blood for highly alloimmunized individuals, and (3) delayed hemolytic or serologic reactions. Acute hemolytic transfusion reactions, though rare, are also possible in alloimmunized patients. In the absence of future transfusions or pregnancies or transplantation, however, RBC alloantibodies are not inherently dangerous.

The clinical consequence of transfusing RBCs expressing an antigen against which a recipient has alloantibodies against varies by situation. Some seemingly incompatible RBCs may continue to circulate in the transfusion recipient for their full life expectancy. In contrast, other RBCs may be completely cleared within days after the transfusion in the form of a DHTR. In DHTRs, the clinical team may observe fever, dark urine, or a hemoglobin that drops back to the pretransfusion level. The blood-bank workup may reveal a seemingly new antibody, which was likely present pretransfusion but below the level of detection. The direct antiglobulin test (DAT) result may be positive, and the eluate may also be positive for the seemingly new antibody. A repeat crossmatch, using a current plasma sample mixed with RBCs from a residual segment of the unit originally transfused, will often now be incompatible. Some new or anamnestic alloantibodies are suspected not by the clinical team but are instead found by the blood bank technologists. These alloantibodies, as described earlier, may qualify the patient to be having a delayed serologic transfusion reaction.

Some patient populations, particularly those with SCD, are at increased risk of transfusion-related complications from RBC alloantibodies. DHTRs with bystander hemolysis (also known as hyperhemolysis), or destruction not only of transfused RBCs but also of the patient’s own RBCs, are a particularly feared and potentially deadly complication in this patient population.36-38 It is likely that transfusion-related mortality secondary to RBC alloimmunization and DHTRs is even greater than previously appreciated.39 Some but not all DHTRs with bystander hemolysis are associated with newly detectable RBC alloantibodies (eg, no new RBC alloantibody may be detected in some reactions), with most occurring in patients with a history of RBC alloimmunization and with the majority associated with the acute onset of reticulocytopenia.32 Recent studies have investigated risk factors and preventative strategies for this complication. It is known, for example, that patients who have had DHTRs with bystander hemolysis are more likely to have this complication again upon future RBC exposure. Increased phosphatidyl serine expression on exogenous RBCs in patients with SCD experiencing bystander hemolysis has been shown, with excessive eryptosis proposed as one potential mechanism.40

Complement activation has also been implicated in bystander hemolysis, with a recent genome-wide association study describing a stop-gain variant in MBL2 (mannose-binding protein C) in some patients with SCD and bystander hemolysis.41 Case reports of the efficacy of eculizumab in the treatment of life-threatening cases of bystander hemolysis further support a role of complement activation in bystander hemolysis,42 though an awareness of the increased risk of meningococcemia after eculizumab treatment is necessary. Evidence of activation of the alternative complement pathway is provided by a recent case report documenting increased C5a, C5b-9, and Bb levels during an episode of bystander hemolysis in a pediatric patient with recurrent episodes of bystander hemolysis.43

RBC alloantibodies are clinically significant not only in transfusion settings but also in pregnancy.44 HDFN occurs when maternal alloantibodies against paternally derived fetal RBC antigens cross the placenta and cause hemolysis and/or suppression of erythropoiesis in the fetus. Up to 1 in every 600 pregnancies is impacted by maternal RBC alloimmunization, with the primary preventative strategy (ie, Rh immune globulin) targeted only at the RhD antigen. Despite the existence of prophylaxis against the RhD antigen, D-alloimmunization remains a leading cause of HDFN. In addition to anti-D alloantibodies, many cases of clinically significant HDFN cases are due to alloantibodies against antigens in the C/c, E/e, Kell, Duffy, Kidd, and MNS blood groups.45-47 It is notable that maternal RBC alloantibodies often lead to concern and serial follow-up evaluations, even in instances in which the baby is ultimately determined not to express the cognate RBC antigen(s). Maternal alloantibodies are significantly less likely to develop when ABO incompatibility exists between the mother and fetus, presumably due to the rapid clearance of fetal RBCs by maternal isohemagglutinins. In addition to blood exchange between the fetus and the mother, another significant risk factor for the formation of RBC alloantibody induction during pregnancy is intrauterine transfusion.48

Though less studied than in transfusion or pregnancy settings, RBC alloantibodies can also potentially be clinically significant in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation settings. Just as isohemagglutinins are significant in major ABO mismatched transplant settings (eg, blood group O recipient, blood group A donor),49 RBC alloantibodies may have implications for the product infusion or donor RBC engraftment in situations in which the donor expresses the cognate RBC antigen in question.50 One study describes an adult with SCD with a preexisting anti-Jka RBC alloantibody that required continued transfusion support for 18 months after a reduced-intensity conditioning transplant from a donor that was Jka positive, due to continued antibody production from persistent recipient plasma cells.51 The role that RBC alloantibodies may play in solid organ transplantation is unclear, though alloantibodies against antigens expressed not only on RBCs but also on the transplanted organ (such as those in the Jk family expressed on renal endothelial cells) may at least theoretically impact transplant outcomes.52-54

Transfusion-recipient disease associations and RBC alloimmunization

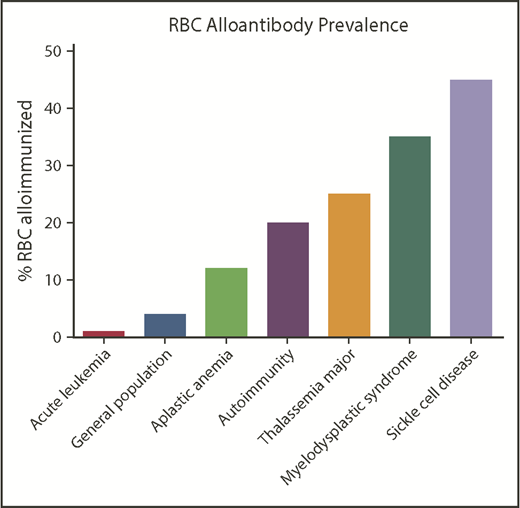

Patients with SCD have among the highest rates of RBC alloimmunization of any population (Figure 3). This may be due in part to the relatively high transfusion burden of patients living with SCD and also to the number of Rh variants (of D, E/e, or C/c) known to occur in patients of African descent. Attention has also recently turned to the possibility that Rh variants in ethnically matched blood donors may impact recipient alloimmunization.55 This risk of alloimmunization against Rh antigens may be balanced, however, by the lower likelihood of being exposed to foreign antigens outside of Rh when blood from donors of similar ethnicity is selected for transfusion.

Approximate RBC alloantibody prevalence by representative disease status. Alloimmunization rates by disease vary significantly by study; the data shown are approximately representative.

Approximate RBC alloantibody prevalence by representative disease status. Alloimmunization rates by disease vary significantly by study; the data shown are approximately representative.

The clinical circumstances surrounding the RBC transfusion are thought to impact the likelihood of the recipient becoming alloimmunized. Patients transfused in their baseline states of health are thought to be less likely to become alloimmunized than patients transfused in a state of inflammation.56 In contrast, having acute chest syndrome at the time of a transfusion is a significant risk factor for becoming alloimmunized,57 as is having a viral illness58 or other inflammatory disorder.59,60 Of note, patients with SCD are, by necessity, transfused during times of inflammation. The type of transfusion (eg, simple vs RBC exchange transfusion) may also impact the likelihood of alloantibody formation.

Other patient populations with high rates of RBC alloimmunization include those with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS),61 thalassemia,62 and autoimmune conditions.63 Patients with MDS who are not undergoing chemotherapy but require ongoing transfusion are more likely to become RBC alloimmunized, whereas those getting immunosuppressive treatment are less likely to develop alloantibodies. Patients with thalassemia have higher alloimmunization rates than the general transfused population, with patients transfused in infancy or early childhood having lower rates of alloimmunization than those intermittently transfused.64,65 Patients with autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis are also relatively likely to become RBC alloimmunized, though transfusions are relatively rarely administered in patients with these diseases. Patients with Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis have an increased risk of RBC alloimmunization than general transfused patients, and those receiving immunosuppressive therapy have reduced rates.66 A positive DAT result is associated with RBC alloantibodies, with a recent study reporting that 41% of hospitalized patients with warm autoantibodies also had RBC alloantibodies63 and with other studies showing associations between a positive DAT test result with RBC alloantibodies in multiple patient populations.30,61 It is not clear at this point whether alloimmunization induces autoantibodies or whether patients with preexisting positive DAT results are more likely to develop new RBC alloantibodies upon RBC exposure.

In contrast, patient populations with lower RBC alloimmunization rates than predicted based on transfusion burden include those with leukemia undergoing chemotherapy.21,67 Patients treated with steroids or other immunosuppressive agents are also less likely to become alloimmunized.68 Infants and very young children have lower RBC alloimmunization rates than those who are middle aged,63 even when adjusted for transfusion exposure.

Multiple studies have investigated whether an immunologic signature may exist in “responders” who form RBC alloantibodies after transfusion compared with “nonresponders” who may be transfused multiple times but never form alloantibodies.69 Polymorphisms in TRIM 21 (Ro52)70 and CD8171 have been implicated in RBC alloimmunization. Few genome-wide association studies have been completed in RBC alloantibody responders and nonresponders, with no large effect responder loci having been described to date.72 It has been proposed that some nonresponder transfusion recipients may actually be tolerized to RBC antigens, with animal studies suggesting that RBC antigen-specific tolerance is possible.73

Other than transfusion, exposure to non-self RBC antigens through pregnancy or IV drug use/needle sharing may also result in RBC alloimmunization. A recent blood donor epidemiologic study from the REDS-III group suggests that a single pregnancy is significantly less likely than a single RBC transfusion to result in RBC alloimmunization.74 However, most alloimmunization in females occurs through pregnancy, given the sheer numbers of previously pregnant compared with previously transfused females. Collectively, the REDS-III donor data emphasize the importance of taking past pregnancies into consideration in RBC alloimmunization studies involving females, while emphasizing the potency of transfused RBCs in stimulating RBC alloantibody formation.

Blood “unit” factors and RBC alloimmunization

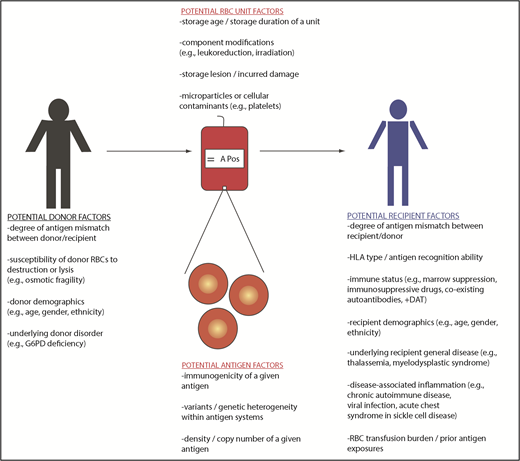

Although RBCs are typically the focus of RBC alloimmunization studies, each transfused “RBC” unit also contains a variable number of WBCs, platelets, and microparticles, among other things (Figure 4). Debate exists regarding the potential role that residual WBCs may play in the likelihood of a recipient becoming RBC alloimmunized,75-77 with the majority of RBC units transfused in the United States being prestorage leukoreduced. A leukoreduced unit may still contain millions of residual WBCs, with US guidelines requiring <5 million WBCs in a leukoreduced RBC unit. Beyond WBCs, their breakdown products (including cytokines and damage-associated molecular patterns)78 microparticles,79 and residual platelets may also play a role in the recipient’s immune response to a transfused RBC unit. Further, the timing between blood collection and processing may influence the storage milieu of the bag, with units subject to an overnight hold prior to processing being noted to have more biologically active components than those processed immediately after collection.79,80 Modifications such as irradiation also damage RBCs, though a recent study showed irradiation did not increase the likelihood of alloantibody formation.81

Another unit factor that may impact RBC immunogenicity is storage duration. Would a unit from the same donor, for example, be more immunogenic after 41 days (vs 5 days) of storage? Or would the answer to this question depend on donor and recipient characteristics as well as component modifications? It has been shown that RBCs near outdate (ie, closer to 41 days of storage) result in increased extravascular hemolysis, increased serum transferrin, and increased non–transferrin-bound iron in healthy volunteers.82 However, multiple studies investigating the impact of storage duration on RBC alloimmunization in humans have not found an association.83-85 Notably, one study suggests an association may exist in transfusion recipients with SCD.86

Blood donor factors and RBC alloimmunization

Aside from RBC antigen characteristics, there are few blood donor factors that have been studied to date regarding their ability to impact recipient RBC alloimmunization. If RBC hemolytic potential impacts the danger signal presented, however, then it is possible that donor factors may come into play (Figure 4). Recent studies have shown, for example, that RBCs from male donors are more susceptible to storage-related breakdown, osmotic fragility, and oxidative hemolysis than RBCs from female donors.87,88 Further, RBCs from donors with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency89 or sickle cell trait90 may be more susceptible to storage hemolysis, as may RBCs from donors of certain races/ethnicities.88

Strategies to prevent RBC alloimmunization

Judicious transfusion or transfusion avoidance is one strategy to prevent RBC alloimmunization. However, often this is not feasible. Matching for some blood group antigens is recommended for patients with SCD to decrease the formation of alloantibodies to matched immunogenic antigens such as D, C/c, E/e, and K.91 However, patients with antigenic variants such as the hybrid RHD*DIIIa-CE(4-7)-D allele that encode a partial C antigen and no conventional RHCE*Ce or *CE allele are at risk of forming anti-C alloantibodies, but this variant will not be discovered unless genotyping is completed.9

Genotyping has recently been shown to be more accurate than phenotyping92 and is increasingly being used to guide transfusion therapy for patients with SCD. Other than SCD, patients with thalassemia major and MDS are also more likely to form alloantibodies against Rh antigens than other blood group systems.62,93 As such, prophylactic matching for these antigens has also been recommended for these at-risk patient groups. Extended matching for patients with RBC autoantibodies has been proposed as a strategy not only to prevent the formation of new RBC alloantibodies but also to more quickly locate compatible RBC units for future transfusions.94 As additional patients and donors are phenotyped or genotyped, the need for uniform registries to store such complex information becomes more pressing.

Pharmacologic suppression of RBC alloantibody formation has not been stringently investigated. As described previously, patients receiving corticosteroids or chemotherapy for disease maintenance are less likely to become alloimmunized.68 Animal models have suggested a role for type 1 interferon in RBC alloantibody induction, with blockade of recipient type 1 interferon receptors being able to prevent alloantibody formation.6,95 Pharmacologic intervention to mitigate or prevent life-threatening DHTRs with bystander hemolysis is also in the process of being studied,42,96 with worldwide collaborations necessary to develop optimal therapies for this relatively rare but life-threatening complication.

Lessons learned from animal models

Multiple murine models have been developed over the past 10-15 years, allowing the investigation of reductionist questions that are simply not feasible to study in humans. While an expansive discussion is beyond our scope, current murine models include those with RBC-specific expression of model antigens (such as HOD97 ) or authentic human blood group antigens (such as KEL98 or human glycophorin A99 ). Studies using these models have highlighted the roles of recipient inflammation,100 type 1 interferon,6,95 CD4+ T cells,101,102 regulatory T cells,103,104 CD40/CD40L interactions,101 interleukin-6 receptor signaling,105 bridging channel dendritic cells,106 and complement107 on RBC alloantibody induction, among others. Murine studies have also shed light on the phenomenon of RBC antigen modulation,108-110 potential mechanisms of immunoprophylaxis therapy,111,112 and, as mentioned earlier, transfusion-associated tolerance induction.73,101 Further, insight into the sequelae of incompatible RBC transfusions113-115 has been provided by animal studies.

Conclusion

Transfusion-associated alloimmunization against RBC antigens can be a clinically significant problem. Identified RBC alloantibodies and reported complications attributed to RBC alloimmunization likely represent only one-third of those that actually exist, given a combination of factors described in this review. As such, what is known about RBC alloimmunization is presumably just the “tip of the iceberg.” Multidisciplinary studies, on the basic science, translational, and clinical levels, are needed to better understand risk factors for antibody development. Strategies to prevent antibody development need to be optimized, as do strategies to mitigate the dangers of existing alloantibodies. Transfusion- and pregnancy-associated alloantibodies have implications that reach far beyond the blood bank and transfusion medicine, with relevance to hematology, oncology, transplantation, obstetrics, and immunology, among other areas.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grants HL126076 and HL132951) (J.E.H.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.A.T. and J.E.H. wrote and edited the manuscript together, and both approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeanne E. Hendrickson, Department of Laboratory Medicine, 330 Cedar St, CB 405, New Haven, CT 06520-8035; e-mail: jeanne.hendrickson@yale.edu.