Abstract

Approximately 35% to 50% of patients otherwise cured of hematologic malignancies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation will develop the pleomorphic autoimmune-like syndrome known as chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD). Since in 2005, National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus panels have proposed definitions and classifications of disease to standardize treatment trials. Recently, the first agent was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for steroid-refractory cGVHD. Despite these advances, most individuals do not achieve durable resolution of disease activity with initial treatment. Moreover, standardized recommendations on how to best implement existing and novel immunomodulatory agents and taper salvage agents are often lacking. Given the potential life-threatening nature of cGVHD, we employ in our practice patient assessment templates at each clinic visit to elucidate known prognostic indicators and red flags. We find NIH scoring templates practical for ongoing assessments of these complex patient cases and determination of when changes in immunosuppressive therapy are warranted. Patients not eligible or suitable for clinical trials have systemic and organ-directed adjunctive treatments crafted in a multidisciplinary clinic. Herein, we review these treatment options and offer a management and monitoring scaffold for representative patients with cGVHD not responding to initial therapy.

Introduction

Although first described nearly 40 years ago,1-3 chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is still a common and often devastating consequence of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) after cure of an otherwise fatal malignancy. Despite completion of randomized phase 3 prophylaxis trials,4,5 preventing cGVHD without compromising its antitumor effects remains a largely unmet goal.6 With >30 000 allogeneic transplantations performed worldwide each year7 and 35% to 50% of recipients developing cGVHD, this complication remains a frequent and formidable foe.8

First-line corticosteroid treatment, alone or with additional agents, has been widely adopted since publication of the initial randomized trial in cGVHD.9 A comprehensive discussion of initial treatments for National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus-defined cGVHD was provided by Flowers and Martin10 in their 2015 article “How we treat chronic GVHD.” Since that publication, 2 major advances have occurred: first, outcome studies have shown that <20% of patients with cGVHD achieve a durable partial (PR) or complete response (CR) and survive 1 year after initial therapy without additional systemic therapy,11 indicating that treatment-refractory cGVHD is relatively common12 and patients likely will require ongoing therapy; and second, in 2017, ibrutinib was approved for steroid-refractory cGVHD,13 and other novel agents14 and existing treatments are being tested in controlled trials as ongoing research continues to elucidate new pathways and targets for drug development.15-18 Choices of salvage therapy for cGVHD represent collective clinical experience and an aggregate consideration of risk of disease mortality, relative treatment toxicity, and availability of regimens and clinical trials.19

If no clinical trial is available or suitable, treatment choice becomes a shared decision, integrating published literature on biology and treatment results with physician experience and patient values.20,21 This process takes time to ensure that patients understand the biology of disease, expectations regarding treatment outcomes, adverse effects, convenience, and cost.22,23 The Seattle Long-Term Follow-Up team, the Chronic GVHD Consortium, and NIH consensus groups have advanced the field by providing guidelines for cGVHD definition, end point reporting, and trial design.11,12,24,25 Ultimately, shared treatment decisions with patients reflect informed intuition, an amalgam of evidence-based facts, consensus opinion, and subjective feelings.20,21 In practice, simplified Web-based versions of NIH consensus guidelines26,27 can be used to objectively monitor treatment-refractory cGVHD.24 Herein, we present our practice of evidence/consensus-based approaches to patients with ongoing cGVHD (cases presented are composites of actual patients).

Case 1

A 40-year-old woman with T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma underwent 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated-donor peripheral blood HSCT after total-body irradiation with 13 Gy and VP-16 conditioning. Despite methotrexate and IV tacrolimus (10-15 ng/mL), grade 4 acute GVHD of the skin developed and was successfully treated with high-dose corticosteroids followed by extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP). After 12 weeks of steroids and ECP, GVHD resolved, and serum tacrolimus levels were maintained at low therapeutic levels before gradually weaning off by 11 months after transplantation. With physical therapy and steroid taper, strength improved. At the 12-month post-HSCT visit, T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma restaging was negative for malignancy, but the patient had had clear clinical decline. She was unable to eat because of severe oral pain, had lost 10 pounds in <2 weeks, and reported sensations of sand in the eyes. On examination, mouth sores and weight loss were apparent; she also had an erythematous macular rash over the flanks, chest, back, and upper thighs, but no sclerosis or restricted range of motion and no pulmonary abnormalities. Laboratory studies showed no hepatic or blood count abnormalities. Infection prophylaxis with posaconazole, acyclovir, and dapsone was provided. Ophthalmology consultants confirmed ocular GVHD. Although opthalmic steroids and cyclosporine (0.05%) afforded improvement, subsequent hyperemia and eye pain developed. Pain was evaluated the same day by the ophthalmologist, and Staphylococcus superinfection was diagnosed and successfully treated.

Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg) was started for cGVHD of moderate global severity, and the patient was enrolled in a clinical trial for new-onset cGVHD, testing addition of a novel agent vs placebo. Three weeks later, the rash had diminished, oral pain had improved, and she had gained weight; steroids were slowly tapered. Three months later, she presented with severe sclerosis over the limbs and asymmetric erythema and sclerosis over the scapula and shoulder consistent with refractory cGVHD, warranting removal from the clinical trial and reinitiation of tacrolimus and high-dose steroids. Ruxolitinib was also added after insurance approval 2 weeks later. The patient continued to improve, and by 25 months post-HSCT, she was working full time while receiving tacrolimus (5-10 ng/mL), ruxolitinib, and low-dose prednisone.

How do we choose immunosuppressive/immunomodulating agents for refractory cGVHD?

Published definitions of global cGVHD severity and steroid response (refractory, intolerant, or dependent [flares during taper with response at higher doses])24,25 effectively guide practitioners regarding when to modify treatment (Figure 1).28 However, outside of clinical trials, the choice of specific agents remains patient and provider specific. Ibrutinib demonstrated clinical improvement in ∼65% of patients when administered in the landmark trial29 to patients with steroid-refractory GVHD with oral or skin disease. These encouraging results in steroid-refractory disease led to a pivotal phase 3 trial examining ibrutinib as upfront cGVHD treatment. A recent study of current practice revealed use of a variety of therapies in refractory cGVHD, including tacrolimus, sirolimus, rituximab, ruxolitinib, hydroxychloroquine, imatinib, bortezomib, ibrutinib, ECP, nilotinib, pomalidomide, and methotrexate, with a wide range of cost effectiveness.23 Therefore, despite US Food and Drug Administration approval of ibrutinib,13 testing of other agents continues, as evidenced by >20 trials currently being conducted.30

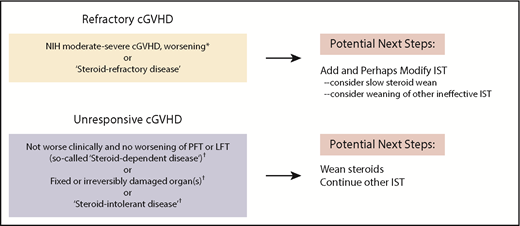

NIH global severity assessments to determine need for intervention in patients with ongoing cGVHD.24,25 Our approach to patients seen in our multidisciplinary clinic for ongoing refractory cGVHD entails assessment of global severity score as well as assessment of treatment response measures per consensus publications (yellow box, top left). Patients without treatment response and/or worsening disease require addition of immunosuppressive therapy (IST) and may also require modification of IST. The group of patients with stable or fixed disease (gray box, bottom left) may have unacceptable toxicity from steroids or may have what has been deemed steroid intolerance. For patients with unresponsive cGVHD or fixed organ damage, tapering steroids is typically recommended (to avoid further steroid toxicity) while maintaining other agents that may be keeping disease in a stable state. *After ≤2 weeks if lung or liver or moderate to severe disease; otherwise, after 4 weeks if no life-sustaining organs are involved. †NIH cGVHD consensus definitions: steroid refractory, steroid dependent, steroid intolerant.24,25 LFT, liver function tests; PFT, pulmonary function tests.

NIH global severity assessments to determine need for intervention in patients with ongoing cGVHD.24,25 Our approach to patients seen in our multidisciplinary clinic for ongoing refractory cGVHD entails assessment of global severity score as well as assessment of treatment response measures per consensus publications (yellow box, top left). Patients without treatment response and/or worsening disease require addition of immunosuppressive therapy (IST) and may also require modification of IST. The group of patients with stable or fixed disease (gray box, bottom left) may have unacceptable toxicity from steroids or may have what has been deemed steroid intolerance. For patients with unresponsive cGVHD or fixed organ damage, tapering steroids is typically recommended (to avoid further steroid toxicity) while maintaining other agents that may be keeping disease in a stable state. *After ≤2 weeks if lung or liver or moderate to severe disease; otherwise, after 4 weeks if no life-sustaining organs are involved. †NIH cGVHD consensus definitions: steroid refractory, steroid dependent, steroid intolerant.24,25 LFT, liver function tests; PFT, pulmonary function tests.

Given these many treatment options, management decisions in refractory ongoing cGVHD are often aided by real-time discussions within a multidisciplinary team. In case 1, we continued 2 agents that were empirically started, noted a response, and pursued a prednisone wean. Although evidence is lacking, use of rapamycin for joint involvement, tacrolimus for myositis, and ruxolitinib for scleroderma can be effective. In our patient, as is commonly done, tacrolimus was reinitiated as a possible steroid-sparing agent. Depending on individual circumstances, tacrolimus may not always be the best choice.31,32 On the basis of randomized phase 2 data33,34 and institutional experience, we often offer ECP for steroid-refractory skin disease, especially sclerodermatous cGVHD. Efficacy data can be found for other agents, including ruxolitinib,35 low-dose interleukin-2,36 nilotinib,37 and rituximab.38,39 Currently, the choice of therapy after failure to achieve PR or CR25 with initial treatment remains patient specific, with comorbidities and history of infectious complications heavily influencing agent choice. These factors, coupled with organ function, toxicities of agents (Table 1), patient preferences, and provider experience, collectively determine the preferred next agent.

Adverse reactions of commonly used therapies in refractory chronic GVHD14

| Agent . | Potential major adverse effects (with major study citations) . | Common (>10%) generally less severe adverse effects . |

|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | Peripheral neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, malignancy relapse106 | Herpes virus reactivation |

| ECP | Vascular access complications107 | Thrombocytopenia |

| FAM | New FDA MedWatch warning; warning only applies to azithromycin use in prophylactic (not treatment) setting108,109 | |

| Ibrutinib (Imbruvica R) | Pneumonia,29 impaired platelet function | Fatigue, muscle pain, peripheral edema |

| Imatinib | Peripheral edema | |

| Interleukin-2 | Injection site induration, infections36 | Constitutional flu-like symptoms |

| MMF (Cellcept) | Viral reactivation, hypertension, pneumonia, posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease110 | GI toxicity, neutropenia, leukopenia |

| Pamolidomide | Tremor, muscle cramps, peripheral neuropathy111 | Skin rash |

| Rituximab (Rituxan R) | Infection, late neutropenia38,39,112 | B lymphopenia |

| Ruxolitinib (Jakafi R) | Viral reactivation/infection, bacterial infections35 | Cytopenias |

| Sirolimus (Rapamune) | TAM when used in combination with calcineurin inhibitors, renal insufficiency,113 proteinuria | Peripheral edema, hyperlipidemia, cytopenias |

| Agent . | Potential major adverse effects (with major study citations) . | Common (>10%) generally less severe adverse effects . |

|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | Peripheral neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, malignancy relapse106 | Herpes virus reactivation |

| ECP | Vascular access complications107 | Thrombocytopenia |

| FAM | New FDA MedWatch warning; warning only applies to azithromycin use in prophylactic (not treatment) setting108,109 | |

| Ibrutinib (Imbruvica R) | Pneumonia,29 impaired platelet function | Fatigue, muscle pain, peripheral edema |

| Imatinib | Peripheral edema | |

| Interleukin-2 | Injection site induration, infections36 | Constitutional flu-like symptoms |

| MMF (Cellcept) | Viral reactivation, hypertension, pneumonia, posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease110 | GI toxicity, neutropenia, leukopenia |

| Pamolidomide | Tremor, muscle cramps, peripheral neuropathy111 | Skin rash |

| Rituximab (Rituxan R) | Infection, late neutropenia38,39,112 | B lymphopenia |

| Ruxolitinib (Jakafi R) | Viral reactivation/infection, bacterial infections35 | Cytopenias |

| Sirolimus (Rapamune) | TAM when used in combination with calcineurin inhibitors, renal insufficiency,113 proteinuria | Peripheral edema, hyperlipidemia, cytopenias |

This list of agents represents a fraction of agents being actively evaluated. Preferred use of any agent still requires validation via larger clinical trials.

ECP, extracorporeal photopheresis; FAM, fluticasone, azithromycin, and montelukast; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; GI, gastrointestinal; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; TAM, transplantation-associated microangiopathy.

Case 1 also illustrates the unfortunate gap between recommendations and practice. Rather than being seen monthly as recommended, the patient did not return until 3 months after initial diagnosis of cGVHD. This was because the patient lived a considerable distance from the transplantation center, a factor that has been associated with poorer outcome.40

What do we use as adjunctive nonsystemic therapies?

Experience and evidence-based consensus opinion support organ-directed topical treatments in cGVHD.41 Although few generalizable standards currently exist, aggressive local therapies may be crucial in managing morbidities.

Adjunctive measures in oral cGVHD

Dexamethasone rinse given twice daily is our preferred topical steroid because it has known benefit in cGVHD,42 although another trial suggested clobetasol oral rinse may be more effective in reducing ulcers and symptoms.43 Some practitioners prefer budesonide rinses over dexamethasone, with studies showing equal efficacy.44 In severe cases, we often use high-potency topical steroids, such as clobetasol 0.05% gel or ointment, 2 to 3 times a day, applied to the buccal mucosal or palate in a manner similar to treatment of autoimmune blistering diseases and oral lichen planus.45,46 Dental trays are useful in applying gels or ointments to the gingiva, but because high-potency topical steroids increase the risk of mucosal candidiasis, we add nystatin rinses.

In patients with ongoing mouth sores, it is important to exclude other contributing causes, including infection and alcohol-based rinses. Even when prescribed as alcohol free, pharmacies may dispense steroid or calcineurin compounded in alcohol-based products, with resulting worsening of symptoms. Oral infections with herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and Candida may also contribute to symptoms. Delay in identifying acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus has been associated with increased hospitalization and kidney injury from acyclovir.47 Oral colonization with Candida occurs in half of immunosuppressed patients and fosters chronic oral ulcers.48,49

To identify dysplasia, referral to an oral surgeon for biopsy should be considered. Oral lichen planus has been associated with development of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and individuals with oral cGVHD are at higher risk of developing SCC.50 Some authors suggest that chronic mucosal inflammation is the predisposing factor for SCC in oral lichen planus and that treatment with topical steroids may help ameliorate risk.51,52 An international case-control study noted that those undergoing allogeneic HSCT who received systemic immunosuppressive therapy for ≥24 months had a 5.6-fold higher relative risk of developing buccal mucosal SCC, and the risk for those with cGVHD was even higher.53 Azathioprine rinse has been evaluated in treatment of oral mucosal inflammatory diseases such as cGVHD,54,55 but we do not include this in our therapy algorithm because of the association of systemic azathioprine with SCC.53

Adjunctive treatments for skin involvement and sclerodermatous cGVHD

Although sclerodermatous dermal manifestations can reverse, they may also be refractory to therapy, with waxing and waning findings. Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine which lesions are fixed and which will improve over time. New agents and concepts of the pathobiology of cGVHD and inflammation-driven fibrosis suggest scleroderma reversibility.15,56,57 In individuals with skin flares, it is crucial to exclude sun exposure or other immune/tissue-inciting events. Trauma from clothing, repetitive movements, or the sun can incite sclerodermatous changes.58 The isomorphic response or Koebner phenomenon (development of disease in otherwise uninvolved skin in response to injury) and the isotopic response (development of disease in areas of prior inflammation or old damage) are described in several cutaneous inflammatory disorders. Injury leading to GVHD can be induced by UV damage, mechanical trauma, irradiation, and infections (viral exanthems).59 Chronic cutaneous GVHD has been observed at injection sites, pressure areas from waistbands, and prior varicella infection. Our first patient’s clinical presentation was striking for the asymmetric sclerosis of the skin over the scapula, which was part of a radiation field before transplantation.60 Measures to minimize additional injury include use of sun protective clothing, UVA- and UVB-blocking sunscreen, and avoidance of constrictive clothing.

Topical agents can be useful adjuncts in the management of cutaneous cGVHD. Tacrolimus 0.1% ointment can improve erythema and pruritus in patients with steroid-refractory skin disease.61 Although dermal application of tacrolimus does not lead to dermal atrophy, the risk of developing skin cancers with prolonged use remains an unsettled issue.62,63 Topical corticosteroids, however, remain a mainstay of therapy, even if controlled trials are lacking.64 Techniques for maximizing benefit include choosing a high-potency topical medication, adequately hydrating the skin before application of topical steroids, and occluding the treated area after application of topical medications. Treatment with high-potency steroids over large body-surface areas can be as effective as and safer than systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of severe cutaneous autoimmune disease.65 Hydrating the skin before application of topical steroids and occlusion with wet wraps or a sauna suit increase penetration of the medication into the skin but also increase the risk of systemic absorption and contribute to cutaneous atrophy and depigmentation. Many practitioners recommend limiting the use of wet-wrap therapy with topical steroids to once a day for no more than 14 days with 10% dilution of either 0.1% triamcinolone or mometasone to minimize the risk of hypothalamic pituitary axis suppression.

Peripheral edema also has been associated with subsequent onset of sclerotic cGVHD and deep cutaneous/fascial involvement.66 Maximizing edema control can provide additional relief and prevent sclerosis in individuals who have significant bipedal edema. Patients who have normal or only minimally impaired arterial flow (indicated by ankle brachial index of ≥0.8) will likely tolerate compression. For more complex edema or if leg ulcers are present, wound clinic evaluation is sought for compression bandage wraps or home compression pumps as appropriate. Finally, we and others find intensive physical therapy provides significant functional improvement.67,68 Comprehensive local therapy offers patients with sclerodermatous lesions potential symptomatic relief.

Adjunctive measures in ocular cGVHD

Eye complaints are common in cGVHD, and ophthalmologists can diagnose involvement based on hallmark findings of new onset of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (ie, dry eye) with conjunctival hyperemia, confluent areas of punctate keratopathy on fluorescein staining, corneal epithelial defects, or overt fibrosis of the tarsal conjunctiva. In contrast to acute GVHD, chronic ocular disease is scored with a combined score using conjunctival hyperemia and corneal staining, which are parameters of sicca.69 Increased exudates reflecting additional pathologic processes require skilled attention. The best early marker for ocular cGVHD, however, is the patient’s history, and revised NIH criteria now score eye disease according to number of times per day that patients use moisturizing eye drops.25 Use of topical steroids and cyclosporine can lessen ocular involvement of the conjunctiva and cornea, and these are used to treat conjunctivitis and keratitis.70-72 Necrotizing keratolysis with corneal thinning (ie, melt) is uncommon in the absence of infection. Although evidence-based standardized treatment of ocular cGVHD is lacking,73 improved understanding of the immunology of ocular surface inflammation and communication with ophthalmologists can ensure implementation of effective therapies beyond steroids. In patients with mild ocular cGVHD, first-line therapy includes both lubrication and ophthalmic prednisolone with cyclosporine (0.05% to 0.5%). High-dose steroids should be used for only short periods.70 If after 4 to 6 weeks there is no improvement, additional therapies are indicated. Systemic agents (eg, FK506, SYK or JAK inhibitors) have been formulated for ophthalmic use.70,74 Although use of autologous serum tears remains controversial, some patients achieve life-improving benefit with a 4- to 8-week course.75,76 The lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 antagonist lifitegrast ophthalmic 5% (Xiidra R) is US Food and Drug Administration approved for dry eye disease77 and was used in our patient. Finally, scleral lenses can be key to improving chronic sicca symptoms or fibrosis of the tarsal conjunctiva.

Ongoing ocular cGVHD is more than a lacrimal gland problem and can occur irrespective of total-body irradiation exposure.78 The pathobiology of ocular cGVHD is thought to be due to atrophy and fibrosis of lacrimal glands. In addition to tear production defects, there is also a lack of oil production by meibomian glands and gland dropout, which is a hallmark finding. Conjunctival complications occur in 4 stages.69 In the first 2 stages, patients have clinical conjunctivitis (hyperemia with or without serosanguinous exudates), as was found in our patient. In stage 3, conjunctival pseudomembranes form. When sloughing of the corneal epithelium occurs, patients have stage 4 conjunctival disease. Both keratinization and development of symblepharon (adhesion of the palpebral conjunctiva to the bulbar conjunctiva) and entropion (rolling inward of the eyelid against the ocular surface) lead to mechanical issues with eye closing and moisture maintenance. Conjunctival and subconjunctival fibrosis and conjunctival/subepithelial scarring occur in cGVHD. In addition to de novo corneal involvement (keratopathy), involvement of the eyelid (including skin) is an important factor in development of eye dryness and downstream pathologic findings on the corneal surface. Corneal surface damage occurs as a result of ongoing trauma from eyelid/eyelash movement over nonlubricated surface.

Corneal abrasion and ulcerations require urgent attention because they can lead to blindness. As with our patient, eye pain or altered vision should prompt same-day ophthalmologic evaluation. In patients not improving, confirmation that artificial tears and other agents are preservative free is imperative, because preservatives can exacerbate irritation. Additionally, a high suspicion for superimposed infection is important. Patients often downplay eye findings when the systemic issues worsen, and re-referral to ophthalmology can be inadvertently delayed. Use of any of several types of scleral lenses (in large part determined by insurance availability) requires proper lens care and hygiene. As with our patient, bacterial or other treatable infections require urgent intervention to avert permanent corneal scarring and blindness.

How do we track patients with ongoing cGVHD and modify immunosuppression?

Individuals with complex and multisystem disease are best served in a multidisciplinary care setting. Transdisciplinary care of recipients of HSCT for autoimmune diseases confirms that dedicated and experienced multidisciplinary teams improve outcomes. Because such clinics are not always available, Syrjala et al79 report a means to integrate long-distance care. Even so, in patients with refractory cGVHD, the level of response or lack of response is often difficult to objectively measure. Another caveat is that providers and patients are reticent to add systemic to topical therapy in certain instances of moderate cGVHD. For example, 3 organs may include limited involvement of mouth, skin, and eye, manageable without systemic immunosuppression, despite being deemed moderate cGVHD by NIH consensus criteria. Accordingly, the NIH consensus working group on clinical trial development has proposed hard primary end points that can be employed in the clinic.80 Although the NIH treatment criteria were designed to assist drug trial reporting, organ-based NIH scoring is also useful in monitoring and treatment.24 Routine blood count checks in our patient did not reveal thrombocytopenia or lymphopenia with eosinophilia,81 2 features associated with poor prognosis. We also routinely check pulmonary function tests (PFTs) at the time of diagnosis and every 3 to 6 months depending on trends, because drop in forced expiratory volume (FEV1) levels precedes radiographic or overt clinical findings, and preemptive treatment is effective. As soon as PFT abnormalities raise concern for lung involvement, we obtain chest computed tomography (CT) scans as part of a workup to rule out infectious etiology. This includes a potential bronchoscopy for diagnostic alveolar lavage fluid. If there is no active infection, we start the FAM regimen and monitor as outlined in “How I treat bronchiolitis obliterans.”82

Individuals with moderate or severe disease require initial weekly reassessments. For consistent assessment, we have the 2014 NIH cGVHD score and global severity score templates in our electronic chart in clinic (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). The NIH cGVHD severity score and a determination as to whether the patient is responding to steroids are useful benchmarks for adjustments in treatment (Figure 1). Clinical responses were recently found to be significantly associated with NIH-defined PR and CR measures. Patients require modification of immunosuppression if they have not at least achieved a PR per NIH criteria or are deemed steroid dependent or intolerant. Individuals who are clinically stable with unresponsive disease despite increasing immunosuppression may have fixed organ damage.25 Although ill defined, expert opinion suggests some nonresponding patients without active cGVHD manifestations do not warrant an increase in therapy, but rather, watchful waiting may be appropriate in some nonresponding patients who do not have active cGVHD manifestations.

As novel agents become available, there may be a tendency for practitioners to start with lower doses of steroids to avoid toxicity when treating newly diagnosed cGVHD or flares after immunosuppressive taper. This leads to ping-ponging dosages. Unless a patient has clearly defined steroid intolerance or clear evidence of cGVHD worsening, we use 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily doses of prednisone for 3 to 4 weeks, guided by the global severity score as to when immunosuppression should be changed. On the basis of experience at many centers, changing agents too frequently has not been beneficial. Recent natural history data from the cGVHD consortium affirm that patients who have a flare of cGVHD on first wean of immunosuppression are highly likely to remain on therapy, and subsequent tapers of agents are associated with reflares.10,12,24,83 When cGVHD flares during immunosuppression wean, readministration of steroids commonly occurs, especially with manifestations involving life-sustaining organs. Data are lacking regarding when and whether to reinstitute steroids or whether other agents would benefit patients. Consistent with consensus group recommendations, it seems reasonable to make treatment changes after 2 unsuccessful attempts to wean steroids within 4 months.28,84,85

Case 2

A 54-year-old man developed moderate cGVHD 7 months after myeloablative matched-sibling HSCT for acute leukemia. Two weeks before the clinic visit, the patient had started 0.5 mg/kg of prednisone for new-onset skin, eye, and mouth findings consistent with cGVHD. Because he did not show up for clinic follow-up, the nurse called and learned he felt too ill to drive to the transplantation center. The next day, the local oncologist evaluated the patient and found that he felt better, with no concerning findings on examination, but had developed new-onset thrombocytopenia. The patient reported substantial symptom relief from local mouth, eye, and skin treatments. Improvements and hyperglycermia led to the local decision to start an early steroid taper. Two weeks later, the patient drove the 3 hours to his transplantation center for evaluation. His complaint was worsening fatigue.

How we routinely screen for associated comorbidity

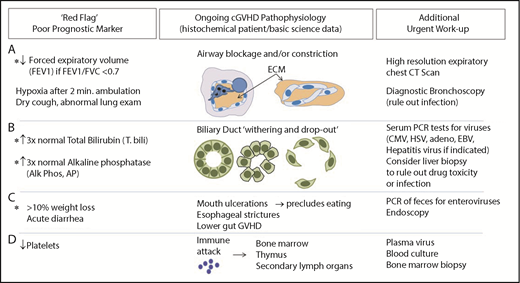

Most individuals with cGVHD experience severe fatigue, but approximately one-third of these patients have reversible causes. Constitutional complaints such as fatigue are especially difficult to address in cGVHD, because patients have become so accustomed to feeling poorly, they are unable to articulate a change. At each clinic visit, systematic review of specific objective prognosticators86,87 can be helpful (Figure 2). Reversible causes of chronic fatigue, such as adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, vitamin-deficiency anemia, or infection, may go undiagnosed. Tertiary adrenal insufficiency can occur on slow steroid tapers and in patients receiving high-dose progestin treatment of anorexia. Overuse of benzodiazepines or opiates may also lead to profound fatigue and decreased cortisol production after steroid weaning. In addition, sirolimus may contribute to fatigue.88 Anemia causing fatigue is not uncommon and is often dismissed as being related to graft function or chronic disease. Patients with cGVHD may have poor nutrition, warranting B12 and folate studies and, for those with known gastrointestinal absorption issues, copper and zinc testing. Reciprocally, concomitant psychological issues warrant frequent readdressing, especially given that cGVHD patients with self-reported depression or anxiety and financial burdens are at risk for poor outcome.89-91 Accordingly, we find same-day telephone calls to no-show clinic patients are useful to assess clinical status and encourage in-person evaluation. Acute or subacute onset of fatigue should always raise suspicion for infection, which may be deadly. Likewise, treatable deep venous thrombosis should be considered, because deep venous thrombosis is relatively common in cGVHD.92 Additionally, cardiopulmonary symptoms should raise suspicion of pleural effusion or pericarditis as serosal manifestations of disease. Therefore, systematic evaluation for poor prognostic factors in cGVHD is imperative (Figure 2).

Assessment of worsening cGVHD reflective of cGVHD pathophysiology that requires urgent attention. (A) Decrease in FEV1 may reflect pathology of bronchiolitis obliterans found in cGVHD. High lung symptom score carries a high risk of death.102 Pulmonary function test abnormalities, specifically evidence of obstruction (FEV1/FVC <0.7) and decreases in FEV1, should raise strong suspicion for development of lung cGVHD, because FEV1 decrease without evidence of restrictive disease may reflect underlying small airway occlusion related to extracellular matrix deposited within or around the airways in cGVHD. Because a drop of FEV1 alone is an indicator of impaired lung function and could be also due to restrictive lung disease, FEV1 is a useful indicator of obstruction only when FEV1/FVC is <0.7 (consistent with obstructive lung disease). (B) Abnormal liver tests may reflect liver pathology in cGVHD that is associated with increased mortality.103 cGVHD of the liver can be diagnosed and tracked in patients using total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase per NIH consensus criteria.25 An increase in total bilirubin occurs when conjugated bilirubin is not excreted, either because of inflammation or loss of the ducts. When the ducts are not functioning properly, alkaline phosphatase rises. Dysfunctional bile ducts can be due to bile duct dropout, presumably a result of cellular damage and preceding inflammation or (more rarely) fibrosis. Infectious or drug-induced causes, in some cases, should be ruled out via biopsy. (C) Significant weight loss with or without diarrhea warrants further investigation because of its association with increased mortality.94,104 The etiology of weight loss may be multifactorial and, importantly, may be reversible (eg, decreased calorie intake related to oral cGVHD, esophageal stricture, or intestinal malabsorption). (D) Abnormalities found on the complete blood count are known prognostic factors,9,79,101,105 including in newly diagnosed cGVHD.81,105 CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Assessment of worsening cGVHD reflective of cGVHD pathophysiology that requires urgent attention. (A) Decrease in FEV1 may reflect pathology of bronchiolitis obliterans found in cGVHD. High lung symptom score carries a high risk of death.102 Pulmonary function test abnormalities, specifically evidence of obstruction (FEV1/FVC <0.7) and decreases in FEV1, should raise strong suspicion for development of lung cGVHD, because FEV1 decrease without evidence of restrictive disease may reflect underlying small airway occlusion related to extracellular matrix deposited within or around the airways in cGVHD. Because a drop of FEV1 alone is an indicator of impaired lung function and could be also due to restrictive lung disease, FEV1 is a useful indicator of obstruction only when FEV1/FVC is <0.7 (consistent with obstructive lung disease). (B) Abnormal liver tests may reflect liver pathology in cGVHD that is associated with increased mortality.103 cGVHD of the liver can be diagnosed and tracked in patients using total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase per NIH consensus criteria.25 An increase in total bilirubin occurs when conjugated bilirubin is not excreted, either because of inflammation or loss of the ducts. When the ducts are not functioning properly, alkaline phosphatase rises. Dysfunctional bile ducts can be due to bile duct dropout, presumably a result of cellular damage and preceding inflammation or (more rarely) fibrosis. Infectious or drug-induced causes, in some cases, should be ruled out via biopsy. (C) Significant weight loss with or without diarrhea warrants further investigation because of its association with increased mortality.94,104 The etiology of weight loss may be multifactorial and, importantly, may be reversible (eg, decreased calorie intake related to oral cGVHD, esophageal stricture, or intestinal malabsorption). (D) Abnormalities found on the complete blood count are known prognostic factors,9,79,101,105 including in newly diagnosed cGVHD.81,105 CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Our patient had no dyspnea at rest, and his lung examination was unrevealing. With prompting, he admitted diminished ability to conduct normal activities, and he had stopped climbing stairs because of dyspnea. After walking <1 minute in clinic, oxygen saturation fell from 100% to 82%. With evidence of lung involvement concerning for cGVHD progression, he was admitted for further workup and management. Empiric antibiotics for atypical and typical organisms were initiated that day. High-resolution CT imaging revealed classic lucencies or air trapping in lung parenchyma during expiration. Methylprednisolone and the FAM regimen were initiated, PFTs were ordered, and tacrolimus was administered, and FEV1 subsequently stabilized. However, during outpatient steroid taper, total bilirubin increased to 4.8 mg/dL. Accordingly, ursodiol and IV tacrolimus were added. A liver biopsy showed cholestasis and bile duct damage with bile duct dropout; trichrome stains showed minimal fibrosis. Bronchoscopy with alveolar lavage had been unrevealing for infectious causes. Over the next 10 days, serum bilirubin improved to 2.5 mg/dL, but the patient had progressive respiratory failure.

How we routinely screen for poor prognostic factors and red flags in patients with ongoing cGVHD

Patients with increased total bilirubin, thrombocytopenia at cGVHD onset, progressive-type cGVHD, increased transplant recipient age, and/or donor HLA mismatch have associated increased mortality.93,94 We find that frequent follow-up visits to the transplantation clinic are critical in assessing GVHD response and detecting potentially life-threatening but reversible complications. We have summarized these red flags and prognostic indicators in Figure 2. As with our patient in case 2, the 2-minute walk test is an objective measure of exertional hypoxia, and studies from the Chronic GVHD Consortium support its prognostic value.95 Bronchiolitis obliterans is a notoriously insidious and deadly manifestation of cGVHD.82 The revised NIH consensus criteria and European consensus statement96 deem FEV1 to be the most useful PFT in this patient population. In individuals without restrictive findings and FEV1/FVC <0.7, FEV1 decline reflects airways that are either obliterated or compressed by the extracellular matrix. Expiratory chest CT scan can then be pathognomonic, highlighting air trapping consistent with bronchiolitis obliterans.

Evaluation for potential liver cGVHD includes determination of whether transaminases are increased to >3 times the normal levels; however, these are not prognostic indicators. Total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase elevations may reflect life-threatening hepatic cGVHD that can be halted with corticosteroid retreatment. Total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase reflect underlying cholestasis and bile duct dysfunction, which lead to abrogation or dropout (Figure 2). Ursodiol may also be of benefit.97 Significant weight loss may result from multiple etiologies, including esophageal stricture.98 Although less well studied than other target organs, gastrointestinal cGVHD has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Persisting diarrhea, nausea, or weight loss should prompt evaluations for Clostridioides difficile or enteric viruses. Similarly, polymerase chain reaction of stool samples for enteroviruses and endoscopy are employed to rule out viral infection. Evidence suggests that endoscopic sampling of both upper and lower gastrointestinal sites increases the likelihood of diagnosing cGVHD and viral etiologies.99 cGVHD mortality, however, remains high in these patients despite endoscopy as part of a diagnostic workup, suggesting that ongoing vigilance is warranted.100

Summary

Improved understanding of GVHD biology15 and identification of new therapeutic targets have enhanced our ability to treat refractory cGVHD, a preeminent complication of allogeneic HSCT. Although guided by clinical trial evidence and expert consensus, therapeutic choices in cGVHD remain patient and provider specific. This approach, which is now being termed interpersonal medicine, affords effective care while taking into account the patient’s circumstances and preferences.101 Along with systemic immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory therapy, aggressive organ-based adjunctive management of cGVHD is warranted. Because this complex disease may present multiple manifestations over time, the continuing care of patients with cGVHD requires frequent monitoring to detect warning signs of disease change or intercurrent, potentially reversible, illnesses.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Duke multidisciplinary clinic providers, especially Matthew Williams and Krista Rowe. Victor L. Perez, Nelson Chao, and Joel Ross assisted with the manuscript.

The work was supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL129061; S.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.S., A.R.C., and K.M.S. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.S. received a research grant from Gilead and served on advisory boards for Pharmacyclics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stefanie Sarantopoulos, Department of Medicine, Box 3961, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710; e-mail: stefanie.sarantopoulos@duke.edu.