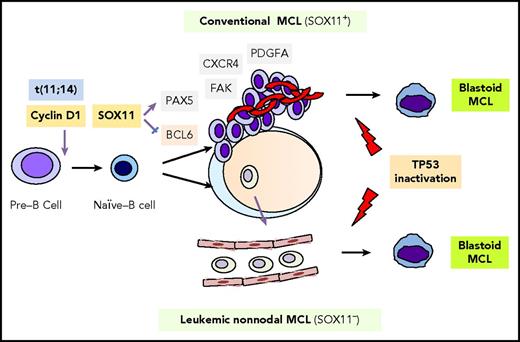

In his lecture series, A Course on English Literature, delivered in 1966 at the University of Buenos Aires, Jorge Luis Borges remarked, “Dickens lived in London. In his book A Tale of Two Cities, based on the French Revolution, we see that he really could not write a tale of two cities. He was a resident of just one city: London.” Comparably, over the past 2 decades, dozens of papers have been published describing the 2 subtypes of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): classical and leukemic, nonnodal. Yet, in the clinical world, there has only been 1 MCL. In this issue of Blood, Clot et al describe the development and validation of a nanostring-based assay that can accurately distinguish between classical and nonnodal MCL, which, in combination with genomic complexity, can provide important prognostic information.1 The biological basis for the differences between MCL subtypes are illuminated in a recent Blood review by Puente et al,2 and the differences are significant. Although both subtypes share a reliance on cell-cycle dysregulation, they arise from distinct cells of origin through different molecular pathways and result in diseases with different presentations and natural histories until problems with genomic instability result in a convergence of the 2 subtypes, frequently seen as the blastoid phenotype and treatment resistance (see figure).

MCL pathogenesis and molecular subtypes. Classical MCL and leukemic, nonnodal MCL are derived from distinct B-cell populations and are transformed via distinct biological pathways. Both subtypes possess t(11;14) and may undergo blastoid transformation, which is frequently associated with disruption of TP53. Reprinted with permission from Puente et al.2

MCL pathogenesis and molecular subtypes. Classical MCL and leukemic, nonnodal MCL are derived from distinct B-cell populations and are transformed via distinct biological pathways. Both subtypes possess t(11;14) and may undergo blastoid transformation, which is frequently associated with disruption of TP53. Reprinted with permission from Puente et al.2

At least 2 reasons for the clinical neglect of MCL subtyping likely exist. First, other than inference based on disease presentation, there is still no simple way to distinguish between subtypes. It is somewhat ironic that a disease named for its clinical presentation cannot be accurately determined based solely on clinical presentation, but it is certainly not the first time in the world of lymphoma (eg, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, can exist outside of the leg). Indeed, leukemic, nonnodal MCL may involve lymph nodes just as classical MCL can have leukemic disease. Other factors lack sufficient specificity, such as SOX11 expression3 or immunoglobulin heavy chain gene mutation status,3 or clinical practicality (eg, gene expression profiling,4 microRNA expression,5 methylation profiling)6 required to assign a subtype. Remedying this issue was the first task addressed by Clot et al. Although the L-MCL16 assay uses a platform that has not yet been commercially adopted, that may soon be changing. Moreover, the nanostring-based MCL35 proliferation signature assay7 may lead the revolution that would carry the L-MCL16 assay along with it. That said, the assay may face some challenges in application. Because it relies on lymphoma cells present in peripheral blood samples, it may be easy in patients with a significant leukemic burden but might be more challenging in patients with low levels of leukemic disease, such as those very early in their disease course or those who have responded to recent treatment.

The second reason that MCL subtyping has not become a standard of care is that, despite the clear biological differences between subtypes, there is not yet a clear rationale to treat them differently. By including an evaluation of genomic complexity, Clot et al attempt to address this second issue. It is now quite clear that patients with classical MCL that harbors a mutation in TP53 have a poor prognosis despite treatment with intensive immunochemotherapy regimens.8 Most patients with leukemic, nonnodal MCL, however, have an excellent prognosis, as evidenced by the fact that only 31% of these patients in the validation set in the Clot et al paper required treatment within 3 years of diagnosis. That said, roughly one-third of the nonnodal patients had a high number of copy number alterations (CNAs) and a prognosis that was similar to the classical MCL patients with high CNA. Putting these details together, it is possible to construct a framework in which patients with high CNA, regardless of subtype, are prioritized in trials (or treatments) with novel agents; patients with classical MCL and low CNA are treated with standard immunochemotherapy regimens; and patients with leukemic, nonnodal MCL with low CNA are either observed or evaluated in the context of window trials in which treatment mechanisms can be evaluated in depth over time. The challenge here is that assays of genomic complexity may not be as straightforward outside of research laboratories.

Although there is clearly more work to be done, the careful observer will note a commonality running through virtually every paper on the subject of MCL subtyping: the laboratory and collaborators of Elias Campo. No doubt they are up to the task.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal