Is that really true? What is clear is that better surrogate end points are needed for follicular lymphoma (FL) clinical trials so we can predict outcomes before they actually occur; to this end, in this issue of Blood, Cottereau et al provide valuable direction.1 FL is the most common of the indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

You can only predict things after they have happened. —Eugene Ionesco

Whereas a small proportion of patients are likely cured with currently available treatments, the majority experience repeated relapses requiring a succession of therapies. Clinical trials in previously untreated patients relying on overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS) as primary end points are challenged by the 10 year survival of 80% in these patients2 resulting in interminable trials such as the recently updated S0016 (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone vs cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone + the radioimmunotherapeutic agent 131I-tositumomab),2 FOLL05 (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone vs rituximab-fludarabine-mitoxantrone vs rituximab, cyclophosphamide, prednisone, and vincristine),3 and Primary Rituximab and Maintenance (rituximab-chemotherapy with or without rituximab maintenance) trial4 having a final analysis being reported out as long as a decade after their initiation. By that time, the clinical questions are often of less interest or irrelevant (radioimmunotherapy is rarely used and 131I-tositumomab is no longer on the market; cyclophosphamide, prednisone, and vincristine and fludarabine are not often the regimens of choice in FL; Primary Rituximab and Maintenance 10-year follow-up data still fail to show a survival benefit for maintenance rituximab). The Follicular Lymphoma Analysis of Surrogate Hypothesis project was created as an attempt to reduce the requisite duration of studies.5 Using data from 13 randomized trials performed before or following the inclusion of rituximab, complete remission at 30 months was determined to be a strong predictor of outcome. Yet, 2 1/2 years is still a considerable delay in results. Casulo et al6 conducted a prospective analysis of the National Lymphocare database, which primarily relied on computed tomography (CT) scans, and established progression of disease at 24 months (POD24) as a surrogate, which has been confirmed by other groups. More recently, progression of disease at 12 months has also been suggested as predictive, with patients without an event at that time point experiencing survival consistent with an age-matched population without lymphoma. Indeed, a national US cooperative group trial will be comparing various regimens in the early relapsing population, with correlative studies designed to identify molecular and genetic abnormalities responsible for treatment failure. Although such data will assist in predicting eventual patient outcome, they currently have limited application to the initial management of FL patients. Reeling the surrogate time point back to assessment immediately posttreatment, restaging positron emission tomography (PET)-CT is valuable in predicting PFS and OS either alone or in combination with assays of minimal residual disease, distinguishing high- vs low-risk patients. Unfortunately, no studies to date have demonstrated benefit from reacting to this information.

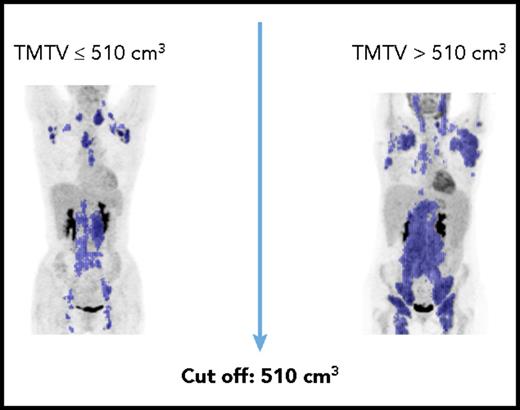

Nevertheless, all of those time points are too little, too late. The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) and FLIPI-2 (F2) are widely used pretreatment prognostic scores, but fail to provide guidance as to appropriate treatment. Toward this aim, Pastore et al7 developed the M7 FLIPI score incorporating the mutational status of 7 genes with the FLIPI-2. However, the particularly high-risk subset of patients accounted for but 28% of cases, and did not provide adequate separation of the majority of patients. Meignan et al8 previously provided evidence that pretreatment total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) in combination with the FLIPI-2 was able to predict PFS and OS (see figure). In their series of patients with advanced FL, using a TMTV cutoff of 510 cm3, in combination with an F2 score 3 to 5, the 5-year PFS was 69% for the low-risk group (0 factors), 46% for the intermediate group (1 factor), and 20% for the high-risk group (both factors). In the current manuscript, these same authors extend their observations to incorporate end of treatment PET-CT results. In concert with the pretreatment study, they demonstrated that patients with no risk factors (MTV <510 cm3, negative end of induction PET-CT) had a 5-year PFS of 67% vs 33% with 1 factor, and only 23% with both high MTV and a positive end of induction scan. These values for low- or high-risk patients do not appear dissimilar from the prior publication using pretreatment TMTV alone8 ; nonetheless, they identify a markedly worse outcome in the intermediate risk group. It would have been interesting to see how the FLIPI-2, which was integral to their former study, affects the current analysis.

Whereas the additive value of the restaging PET-CT may predict outcome better than either study alone, it falls short of our goal. The Holy Grail for FL patients remains the accurate prediction of patient outcome before treatment. Rather than waiting to retreat with residual disease or upon recurrence, the primary focus should be on improving predictability before initial therapy by incorporating other correlative studies including the M7 FLIPI. Sarkozy et al9 suggested that a quantitative clonotypic assay (Clonoseq) or other next-generation sequencing performed pretreatment predicts outcome. Studies are under way assessing the additive value of such assays with TMTV.

Risk-adapted trials using appropriate biomarkers need to distinguish those patients likely to do well with standard treatments who might require less therapy. Those unlikely to do so would be spared the time delay and toxicity of unsuccessful treatments and instead would be referred for novel therapeutic strategies, hopefully leading to improved patient outcome. It will be our greatest challenge to figure out what those therapies are.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal