TO THE EDITOR:

The factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation is the most common genetic risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE) among whites, with a prevalence varying from 3% to 15% depending on the geographical location.1,2 The pathophysiological mechanism of the increased thrombotic risk in FVL carriers is subsumed under the concept of activated protein C (APC) resistance. The mutant FVL gene product lacks 1 target site for the APC-catalyzed inactivation of activated factor V (FVa).3 As consequence, inactivation of FVa is impaired, resulting in delayed downregulation of thrombin formation.4 Although the laboratory phenotype of APC resistance shows a high degree of homogeneity among FVL carriers, the clinical phenotype is highly diverse, ranging from recurrent VTE to a lifelong asymptomatic course. One factor that might modulate the thrombogenicity of the FVL mutation is the anticoagulant capacity of the endothelium as haplotypes and polymorphisms of the endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) gene have been suggested as risk factors for VTE.5,6

To test the in vivo impact of the FVL mutation on coagulation activation and on the subsequent endothelial-dependent anticoagulant response, we combined standardized and low-dose activation of coagulation by recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) with subsequent monitoring of coagulation biomarkers, including measurement of APC using a highly sensitive oligonucleotide-based enzyme capture assay.

Blood samples were collected from 81 non-FVL carriers (mean age, 30 years; range, 18-60 years; 42 female) and 22 FVL carriers (mean age, 39 years; range, 18-60 years; 15 female; 8 homozygous) without a history of VTE. Single IV bolus injections of 15 µg/kg rFVIIa were performed in a subgroup thereof that comprised 12 non-FVL carriers, 12 heterozygous carriers, and 3 homozygous FVL carriers. Blood samples were drawn immediately before and 10 minutes, 30 minutes, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8 hours after rFVIIa administration. After discarding the first 2 mL, blood was drawn into citrate tubes (10.5 mmol/L final concentration). Citrate tubes additionally containing aprotinin and bivalirudin (final concentration of 10 µmol/L and 250 µg/mL, respectively) were used for APC measurement. Plasma samples were obtained by centrifugation (2600g, 10 minutes) within 30 minutes after blood draw and stored at less than −70°C. The coagulation biomarkers prothrombin activation fragment 1 + 2 (F1+2), thrombin-antithrombin complex (TAT), and D-dimer were determined using commercially available assays. The oligonucleotide-based enzyme capture assay for APC detection was performed as previously described.7 Additional details on the study population and methods are presented in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site). The study proposal was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of the University Hospital of Bonn. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

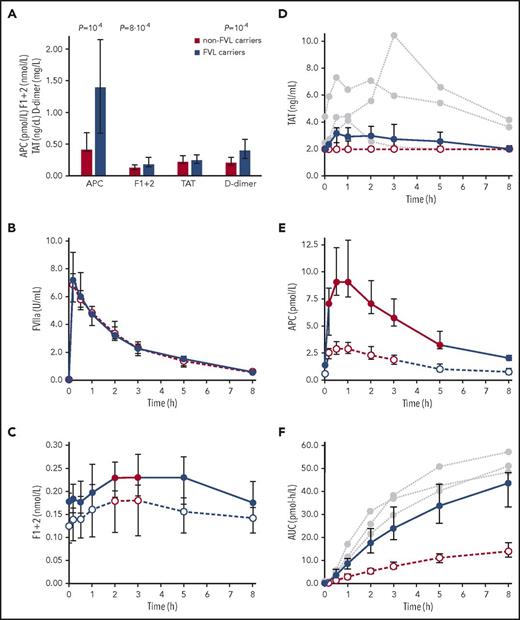

Measurements of parameters in a quiescent state of hemostasis revealed higher plasma levels of APC, F1+2, and D-dimer in FVL carriers than in non-FVL carriers, whereas there was no statistically significant difference between TAT levels in both groups (Figure 1A). These data support and extend previous observations of increased F1+2 levels in a smaller number of FVL carriers.8-10 The constant increase in thrombin formation and basal APC plasma levels raises the question of to what extent the FVL mutation alters the kinetics of coagulant reactions after in vivo coagulation activation.

Hemostasis parameters in non-FVL carriers and FVL carriers. (A) Plasma concentrations of APC, F1+2, TAT, and D-dimer were measured in FVL carriers without a history of thrombosis (n = 22, thereof 8 homozygous), and in non-FVL carriers (n = 81). Data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). The Mann-Whitney test was used to calculate significance; P values <.05 are shown. Plasma levels of FVIIa (B), F1+2 (C), TAT (D), and APC (E) were measured before (t = 0) and after IV injection of 15 µg/kg rFVIIa in 12 heterozygous FVL carriers without a history of thrombosis (●, solid lines) and in 12 non-FVL carriers (○, intersected lines). Red data points and connections indicate a significant increase (P < .05) compared with baseline (t = 0). P values were calculated using the paired Student t test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, depending on the normality of data. The Bonferroni method was applied to correct for multiple testing. Plasma levels of TAT in 3 homozygous FVL carriers are additionally shown (gray circles, dotted lines). (F) Area under the APC generation curve (AUC).

Hemostasis parameters in non-FVL carriers and FVL carriers. (A) Plasma concentrations of APC, F1+2, TAT, and D-dimer were measured in FVL carriers without a history of thrombosis (n = 22, thereof 8 homozygous), and in non-FVL carriers (n = 81). Data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). The Mann-Whitney test was used to calculate significance; P values <.05 are shown. Plasma levels of FVIIa (B), F1+2 (C), TAT (D), and APC (E) were measured before (t = 0) and after IV injection of 15 µg/kg rFVIIa in 12 heterozygous FVL carriers without a history of thrombosis (●, solid lines) and in 12 non-FVL carriers (○, intersected lines). Red data points and connections indicate a significant increase (P < .05) compared with baseline (t = 0). P values were calculated using the paired Student t test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, depending on the normality of data. The Bonferroni method was applied to correct for multiple testing. Plasma levels of TAT in 3 homozygous FVL carriers are additionally shown (gray circles, dotted lines). (F) Area under the APC generation curve (AUC).

IV administration of endotoxin or activated coagulation factors is an established model in which to study alterations in the kinetics of coagulant reactions in vivo.11-14 In this study, we used rFVIIa to achieve standardized and limited coagulation activation without any inflammatory reactions as observed with endotoxin administration. In previous studies, a significant thrombin burst as characterized by an increase in F1+2 plasma levels was achieved by administration of rFVIIa at the low dose of 15 µg/kg.15 Hence, this dosage was selected for our clinical study primarily to minimize the potential thromboembolic risk associated with rFVIIa administration, although higher doses of up to 160 µg/kg have been administered without serious or thromboembolic events.16,17

Application of rFVIIa was well tolerated by all subjects without any adverse events and without an increase in D-dimer levels (supplemental Figure 1), giving further evidence for the safety of this low-dose rFVIIa regimen. The pharmacokinetic profiles of rFVIIa in heterozygous FVL carriers and non-FVL carriers were essentially identical (Figure 1B) and as expected from previous reports.15,16 Plasma levels of F1+2, TAT, and APC measured before and after rFVIIa injection are shown in Figure 1C-E; a comparison of baseline and peak values is provided in Table 1. Starting from higher baseline values, the relative increase of F1+2 after rFVIIa administration was similar in heterozygous FVL carriers and non-FVL carriers, indicating that rFVIIa-induced increased rates of thrombin formation in both groups. Median TAT levels remained unchanged in non-FVL carriers and a slight increase in heterozygous FVL carriers was statistically significant only before Bonferroni correction. The increase of TAT in 2 homozygous FVL carriers exceeded that of heterozygous carriers. On a molar level, the TAT increase was lower than expected from the F1+2 values. The most likely explanation for this discrepancy is the shorter TAT half-life of 44 minutes in comparison with the F1+2 half-life of ∼2 hours.18

rFVIIa-induced changes of biomarkers

| Subjects . | Non-FVL carriers, n = 12 . | Heterozygous FVL carriers, n = 12 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ct=0 . | Cpeak . | P . | Ct=0 . | Cpeak . | P . | |

| F1+2, nmol/L | 0.13 (0.09-0.19) | 0.18 (0.10-0.21) | .048 | 0.18 (0.10-0.20) | 0.23 (0.19-0.28) | .022 |

| TAT, ng/mL | <2.0 (<2.0-<2.0) | <2.0 (<2.0-2.65) | NS | <2.0 (<2.0-2.31) | 3.16 (2.05-3.60) | NS* |

| APC, pmol/L | 0.63 (0.50-1.20) | 2.93 (2.44-3.58) | .025 | 1.44 (1.21-2.08) | 9.09 (7.69-12.88) | 7 × 10−5 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 0.28 (0.23-0.37) | 0.31 (0.25-0.44) | NS | 0.35 (0.26-0.44) | 0.43 (0.35-0.53) | NS |

| Subjects . | Non-FVL carriers, n = 12 . | Heterozygous FVL carriers, n = 12 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ct=0 . | Cpeak . | P . | Ct=0 . | Cpeak . | P . | |

| F1+2, nmol/L | 0.13 (0.09-0.19) | 0.18 (0.10-0.21) | .048 | 0.18 (0.10-0.20) | 0.23 (0.19-0.28) | .022 |

| TAT, ng/mL | <2.0 (<2.0-<2.0) | <2.0 (<2.0-2.65) | NS | <2.0 (<2.0-2.31) | 3.16 (2.05-3.60) | NS* |

| APC, pmol/L | 0.63 (0.50-1.20) | 2.93 (2.44-3.58) | .025 | 1.44 (1.21-2.08) | 9.09 (7.69-12.88) | 7 × 10−5 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 0.28 (0.23-0.37) | 0.31 (0.25-0.44) | NS | 0.35 (0.26-0.44) | 0.43 (0.35-0.53) | NS |

Data are presented as median and interquartile range. P values describe differences of peak values from baseline and were calculated using the paired Student t test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Cpeak, the highest plasma concentration measured within 8 hours after IV injection of 15 µg/kg rFVIIa; Ct=0, the plasma concentration measured at baseline; NS, not significant.

P = .030 before Bonferroni correction.

APC showed the clearest response to rFVIIa among the studied parameters, and a significantly greater increase in heterozygous FVL carriers than in non-FVL carriers (Figure 1E). The area under the APC generation curve (AUC) of the homozygous FVL carriers was greater than the median AUC of the heterozygous carriers (Figure 1F; supplemental Figure 2), but the overall number of homozygous probands was too low to come to a clear conclusion. The enhanced APC response in FVL carriers can be explained by increased rates of protein C activation and/or by displacement of EPCR-bound APC because it has been shown that APC and FVIIa bind with similar affinities to EPCR.19 The time delay of ∼1 hour between the FVIIa peak and the APC peak, together with the increased rates of thrombin formation, favor the concept of increased de novo APC formation.

Although there is no direct evidence that increased APC plasma levels result in enhanced anticoagulant activity, the dose-dependent prolongation of clotting times, such as the activated partial thromboplastin time in response to exogenously added APC, makes it most probable that even in vivo–enhanced APC levels more effectively downregulate prothrombinase activity and thereby modify the prothrombotic risk in FVL carriers. Further studies, including FVL carriers with a history of spontaneous thrombosis, however, are required to analyze whether a dysbalance between increased thrombin formation and an impaired APC response enhances the prothrombotic potential of the FVL mutation, and whether the APC levels measured in this study were a manifestation of a clinically relevant anticoagulant response. Although endothelial-associated APC has been suggested to convey much of the endothelial-protective effects of APC,20 the increased APC plasma levels could possibly explain the slightly decreased risk of FVL carriers developing severe sepsis from infection and the increased survival rates of FVL carriers in severe sepsis.21,22

In summary, this study shows that the FVL mutation enhances in vivo thrombin generation and subsequent endothelial cell–dependent APC formation, as evidenced by accelerated prothrombin activation rates and enhanced APC plasma levels after coagulation activation in thrombosis-free FVL carriers compared with healthy non-FVL carriers.

Presented in abstract form at the 59th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Atlanta, GA, 10 December 2017.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Stiftung Hämotherapie-Forschung (Hemotherapy Research Foundation).

F.I.W. is a doctoral candidate at the University of Bonn and this work will be part of her thesis.

Authorship

Contribution: H.R., J.M., and B.P. designed the experiments; H.R., C.B., and F.I.W. collected the data; H.R. and F.I.W. analyzed the data; and H.R., F.I.W., J.O., and B.P. drafted and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Heiko Rühl, Institute of Experimental Hematology and Transfusion Medicine, University Hospital Bonn, Sigmund-Freud-Str 25, D-53127 Bonn, Germany; e-mail: heiko.ruehl@ukbonn.de.

REFERENCES

Author notes

H.R. and F.I.W. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal