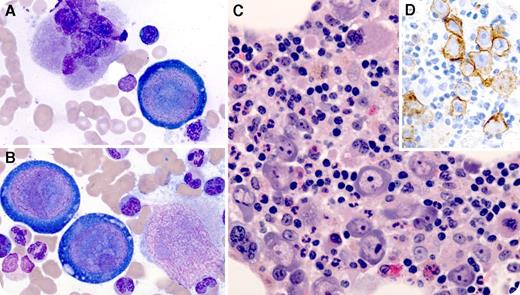

A 66-year-old man developed dizziness and fatigue 2 months after orthotopic heart transplant for ischemic cardiomyopathy. His immunosuppressive regimen included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He was found to be severely anemic (hemoglobin, 6.6 g/dL). Clinical studies excluded acute blood loss or hemolysis. Reticulocyte count was 0.2%, and erythropoietin level was 750 mIU/mL (range, 3-19 mIU/mL). A bone marrow aspirate smear revealed large atypical cells with prominent intranuclear inclusions and vacuolated cytoplasm (panels A and B; original magnification ×100, Wright-Giemsa stain), which were also evident on a hematoxylin and eosin stain of the aspirate clot (panel C; original magnification ×40). Megakaryocytes and myeloid precursors were easily identified; however, there was essentially no erythroid maturation. E-cadherin stain confirmed that atypical cells were virally transformed erythroid precursors (panel D; original magnification ×40). Serum parvovirus B19 polymerase chain reaction was positive. Anti-parvoviral immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG titers were within normal limits.

Giant virally transformed proerythroblasts and erythroid maturation arrest are classic findings of parvovirus B19–associated pure red cell aplasia. Although most adults acquire lifelong immunity to parvovirus B19 from exposure in childhood, reinfection can occur in the setting of immunocompromise, leading to prolonged severe anemia. In retrospect, our patient had had contact with a granddaughter with high fevers and red cheeks several weeks before his initial presentation. His hemoglobin recovered after supportive transfusions and 5 days of IV immunoglobulin. He remains well 2 years posttransplant.

A 66-year-old man developed dizziness and fatigue 2 months after orthotopic heart transplant for ischemic cardiomyopathy. His immunosuppressive regimen included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He was found to be severely anemic (hemoglobin, 6.6 g/dL). Clinical studies excluded acute blood loss or hemolysis. Reticulocyte count was 0.2%, and erythropoietin level was 750 mIU/mL (range, 3-19 mIU/mL). A bone marrow aspirate smear revealed large atypical cells with prominent intranuclear inclusions and vacuolated cytoplasm (panels A and B; original magnification ×100, Wright-Giemsa stain), which were also evident on a hematoxylin and eosin stain of the aspirate clot (panel C; original magnification ×40). Megakaryocytes and myeloid precursors were easily identified; however, there was essentially no erythroid maturation. E-cadherin stain confirmed that atypical cells were virally transformed erythroid precursors (panel D; original magnification ×40). Serum parvovirus B19 polymerase chain reaction was positive. Anti-parvoviral immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG titers were within normal limits.

Giant virally transformed proerythroblasts and erythroid maturation arrest are classic findings of parvovirus B19–associated pure red cell aplasia. Although most adults acquire lifelong immunity to parvovirus B19 from exposure in childhood, reinfection can occur in the setting of immunocompromise, leading to prolonged severe anemia. In retrospect, our patient had had contact with a granddaughter with high fevers and red cheeks several weeks before his initial presentation. His hemoglobin recovered after supportive transfusions and 5 days of IV immunoglobulin. He remains well 2 years posttransplant.

For additional images, visit the ASH IMAGE BANK, a reference and teaching tool that is continually updated with new atlas and case study images. For more information visit http://imagebank.hematology.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal