In this issue of Blood, Jawhar and colleagues describe the results of quantitative KIT D816V allele burden testing and next-generation sequencing of a panel of myeloid genes to characterize molecular correlates of response and progression on midostaurin therapy in patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis.1

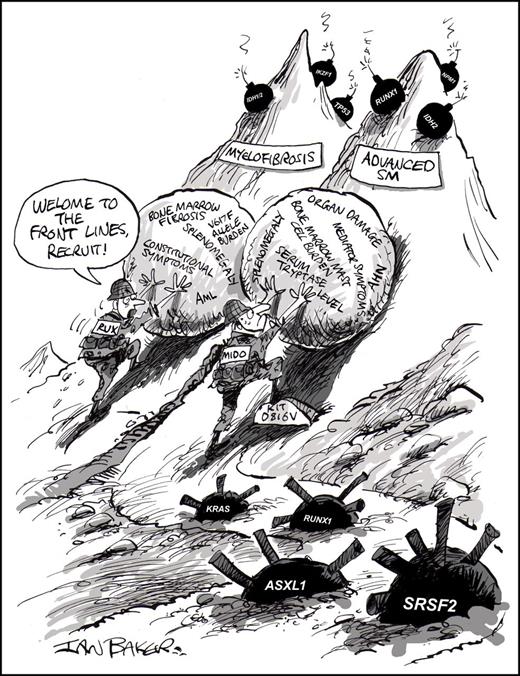

In advanced SM and myelofibrosis, midostaurin (MIDO) and ruxolitinib (RUX), respectively, must navigate complex mutational landscapes while trying to impact similar disease-related burdens. Professional illustration by Ian Baker; conceived by Jason Gotlib.

In advanced SM and myelofibrosis, midostaurin (MIDO) and ruxolitinib (RUX), respectively, must navigate complex mutational landscapes while trying to impact similar disease-related burdens. Professional illustration by Ian Baker; conceived by Jason Gotlib.

On 28 April 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the oral multikinase inhibitor midostaurin for the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed FLT3 mutation–positive acute myeloid leukemia in combination with chemotherapy and for patients with advanced subtypes of systemic mastocytosis (SM), such as aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM), SM with an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN), and mast cell leukemia (MCL). Midostaurin’s target profile includes wild-type and D816V-mutated KIT.2 The oncogenic variant of KIT can be detected in 90% of SM patients with highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction assays.3 The identification of KIT D861V not only fulfills 1 minor diagnostic criterion for SM, but also informs the appropriate use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for mast cell cytoreduction because this mutation is imatinib-resistant.

Patients with ASM, SM-AHN, and MCL share the common thread of reduced life expectancy, often related to progressive organ damage, complications of the associated hematologic neoplasm (AHN), or both. Neoplastic mast cells usually transit the blood as invisible marauders, plundering organs in their wake. The rarity of advanced SM and its protean manifestations of mast cell activation and organopathy often result in delayed diagnosis and treatment.

I think of advanced SM and late-stage myelofibrosis (MF) as “fraternal twins” because of their shared clinical and biological features. Patients often exhibit a hypercatabolic state with debilitating constitutional symptoms, hepato/splenomegaly, progressive organ impairment, and bone marrow failure with potential for transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The canonical driver mutations in SM and myelofibrosis, KIT D816V and JAK2 V617F, respectively, often coexist in a Darwinian ecosystem of multiple mutated clones. This is especially true in SM-AHN, whose genetic complexity partly reflects the marriage of 2 neoplasms, and stands in contrast to the comparatively bland clonal landscape of indolent SM that is usually restricted to KIT D816V.4 In both neoplasms, a similar set of genes influence prognosis: mutations in SRSF2, ASXL1, or RUNX1 (S/A/Rpos) adversely impact survival in SM5 ; in primary myelofibrosis, mutations in SRSF2, ASXL1, EZH2, or IDH1/2 are associated with worse overall and/or leukemia-free survival independent of the Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System-Plus scoring system.6 Several groups have used these molecular data to generate mutation-enhanced clinical prognostic models to optimize risk stratification for patients with advanced SM7 and myelofibrosis.

If advanced SM and myelofibrosis are fraternal twins, then midostaurin and ruxolitinib may be linked as a band of brothers, waging Sisyphean battles to reclaim disease control amid a minefield of mutations (see figure). Ruxolitinib produces marked improvements in splenomegaly and MF-related disease symptoms, but meaningful reductions in bone marrow fibrosis or JAK2 V617F allele burden are uncommon.8 In the pivotal global trial of midostaurin, the overall response rate was 60%, of which 75% were major responses, indicating normalization of ≥1 SM-related organ damage finding.9 In addition, a majority of evaluable patients experienced reduction in splenomegaly and/or a >50% decrease in the serum tryptase level or bone marrow mast cell burden. Decreases in spleen size with ruxolitinib and reversion of organ damage by midostaurin are clinically relevant beachheads in the fight against MF and SM that are inextricably associated with improved quality of life.

Elucidating the biomarkers that predict response and progression with targeted therapies is a critical part of strategizing in these “myeloid wars.” In their report, Jawhar and colleagues analyzed 38 patients with advanced SM who were treated with midostaurin on the pivotal trial or via a compassionate use program. They found that the overall response rate, median duration of midostaurin treatment, and overall survival (OS) were significantly higher in patients with a S/A/Rneg (vs S/A/Rpos) mutation profile and in subjects with a ≥25% reduction in the KIT D816V allele burden (“KIT-responders”) vs <25% reduction (“KIT-nonresponders”) by using allele-specific quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Notably, KIT-responder status was the strongest and only on-treatment marker that retained statistical significance in a multivariate analysis of OS. These molecular data complement a post hoc multivariate analysis of the pivotal trial, which showed that achieving a response according to modified Valent criteria or a ≥50% reduction in bone marrow mast cell burden on midostaurin therapy was associated with improved survival.9

The biological resemblance between advanced SM and MF also extends to the nature of progression on therapy. Among SM patients treated with midostaurin, 5 of 6 patients who developed secondary AML or MCL harbored the S/A/Rpos molecular profile.1 Irrespective of KIT-responder status, progression was also linked to the appearance of new mutations or an increase in the variant allele frequency of non-KIT D816V mutations (eg, K/NRAS, RUNX1, IDH2, and NPM1) that were present before starting midostaurin. This baseline genetic heterogeneity and secondary resistance owing to dynamic evolution of mutant subclones is the modus operandi of many myeloid neoplasms. It also closely mimics the experience of MF patients treated with ruxolitinib, where mutations in ASXL1, EZH2, or IDH1/2 (as well as the total number of mutated genes on a next-generation sequencing panel) negatively impacted spleen response, time to discontinuation, and OS.10 Interestingly, no additional mutations in KIT or JAK2 that confer resistance to midostaurin or ruxolitinib, respectively, have been identified to date.

How do we use the information generated by Jawhar and colleagues? First, the poor-risk S/A/Rpos profile should not engender nihilism about treating an already challenging advanced SM population. Although historical comparisons with unselected cohorts should be approached cautiously, they found that midostaurin-treated patients carrying these mutations experienced significantly longer survival than those who had not received midostaurin. The authors’ data also reinforce that SM-AHN should not be considered a monolithic entity, because outcomes within specific types of AHN may vary widely according to the molecular architecture of their hybrid disease. This mutational complexity not only forebodes challenges with midostaurin, but also with other therapies, such as cladribine and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Therefore, testing of novel agents or combination strategies with midostaurin will similarly benefit from dynamic assessments of the molecular determinants of response. Lastly, if deeper reduction of KIT D816V allele burden is a key biomarker of response and survival, then the next generation of selective KIT D816V inhibitors, such as BLU-285 and DCC-2618, may be able to build on the gains produced by midostaurin.

Unlike King Sisyphus who was eternally condemned to the futile task of rolling a huge boulder up a steep hill, only to have it perpetually roll back down as it reached the top, patients with advanced SM have reason for optimism: the findings of Jawhar and colleagues provide a molecular footing to help navigate the steep mountain toward cure.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.G. served as Chairman of the Study Steering Committee for the Novartis-sponsored global trial of midostaurin in advanced SM. He has received funding to conduct trials of midostaurin and BLU-285 in advanced SM. He has also served on advisory boards and received honoraria from Novartis, Blueprint Medicines, and Deciphera.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal